This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Per Honor et Gloria (talk | contribs) at 14:05, 26 February 2006 (→Artistic legacy: details). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 14:05, 26 February 2006 by Per Honor et Gloria (talk | contribs) (→Artistic legacy: details)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

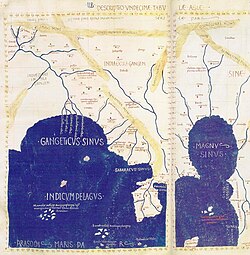

Maximum extent of Indo-Greek territory circa 175 BCE (drawn from textual information in Tarn). | |

| Languages | Greek Prakrit (Kharoshthi script) |

|---|---|

| Religions | Greek gods |

| Capitals | Alexandria in the Caucasus Sirkap/Taxila Sagala/Sialkot |

| Area | Northwestern Indian subcontinent |

| Existed | 180 BCE–10 CE |

The Indo-Greek Kingdom (or sometimes Greco-Indian Kingdom) covered various parts of northwest and northern India from 180 BCE to around 10 CE, and was ruled by a succession of more than thirty Greek kings, often in conflict with each other. The kingdom was founded when the Greco-Bactrian king Demetrius invaded India in 180 BCE, ultimately creating an entity which seceded from the powerful Greco-Bactrian Kingdom centered in Bactria (today's northern Afghanistan).

During the two centuries of their rule, the Indo-Greek kings combined the Greek and Indian languages and symbols, as seen on their coins, and blended Ancient Greek, Hindu and Buddhist religious practices, as seen in the archaeological remains of their cities and in the indications of their support of Buddhism. The Indo-Greek kings seem to have achieved a level of cultural syncretism with no equivalent in history, the consequences of which are still felt today, particularly through the diffusion and influence of Greco-Buddhist art.

The Indo-Greeks ultimately disappeared as a political entity around 10 CE following the invasions of the Indo-Scythian, Indo-Parthian and Kushans, although pockets of Greek populations probably remained for several centuries longer. The Indo-Greek Kingdom also has the distinction of being the last Hellenistic kingdom in history.

Early History

- Main article:History of the Indo-Greek Kingdom

Local turmoil preceded the invasion of northern India undertaken by Demetrius, son of the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus, circa 180 BCE. General Pusyamitra Sunga had destroyed the ruling Mauryan King and had recently founded the Sunga dynasty (185–78 BCE). Written evidence of the initial Greek invasion survives in the Greek writings of Strabo and in Sanskrit in the records of Patanjali, Kālidāsa, and in the Yuga Purana, among others. Coins and architectural evidence also attest to the extent of the initial Greek campaign.

Evidence of the initial invasion

According to Strabo, Greek conquest temporarily went as far as the Sunga capital Pataliputra (today Patna) in eastern India:

- "Those who succeeded Alexander advanced beyond the Hypanis, to the Ganges and Pataliputra." (Strabo, 15.698)

Indian records describe Greek attacks on Mathura, Panchala, Saketa, and Pataliputra, notably those mentioned by Patanjali, a grammarian and commentator on Panini, around 150 BCE: in the Mahābhāsya , Patanjali described the invasion in two examples using the imperfect tense of Sanskrit, denoting a recent event: "Arunad Yavanah Sāketam" ("The Yavana were besieging Saketa") and "Arunad Yavano Madhyamikām" ("The Yavana was besieging Madhyamika (the "Middle country")").

Accounts of battles between the Greeks and the Sunga are also found in the Mālavikāgnimitra , and the Yuga Purana, which describes Indian historical events in the form of a prophecy:

- "After having conquered Saketa, the country of the Panchala and the Mathuras, the Yavanas, wicked and valiant, will reach Kusumadhvaja. The thick mud-fortifications at Pataliputra being reached, all the provinces will be in disorder, without doubt. Ultimately, a great battle will follow, with tree-like engines (siege engines)." ("Gargi-Samhita," Chapter Five of the Yuga Purana.)

Ultimately, the Indo-Greeks toppled the local Kings, and established their own rule:

- "The Yavanas (Greeks) will command, the Kings will disappear." (Gargi-Samhita, Yuga Purana chapter, No7).

To the south, the Greeks occupied the areas of the Sindh and Gujarat down to the region of Surat (Greek: Saraostus) near Mumbai (Bombay), including the strategic harbour of Barigaza (Bharuch), as attested by several writers (Strabo 11; Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, ch.41) and as evidenced by coins dating from the Indo-Greek ruler Apollodotus I:

- "The Greeks... took possession, not only of Patalena, but also, on the rest of the coast, of what is called the kingdom of Saraostus and Sigerdis." (Strabo 11.11.1 )

The city of Sirkap, today in northwestern Pakistan, was built according to the "Hippodamian" grid-plan characteristic of Greek cities, suggesting it may have been built by Demetrius. Numerous Hellenistic artifacts have been found, in particular coins of Greco-Bactrian kings and stone palettes representing Greek mythological scenes. Some of them are purely Hellenistic, others indicate an evolution of the Greco-Bactrian styles found at Ai-Khanoum towards more indianized styles. For example, accessories such as Indian ankle bracelets can be found on some representations of Greek mythological figures such as Artemis.

Retreat

Obv: King Menander throwing a spear.

Rev: Athena with thunderbolt. Greek legend: BASILEOS SOTĒROS MENANDROU "Of King Menander, the Saviour".

The first invasion was completed by 175 BCE, as the Indo-Greeks contained the Sungas to the area eastward of Pataliputra, and established their rule on the new territory. Back in Bactria however, around 170 BCE, an usurper named Eucratides managed to topple the Euthydemid dynasty. He took for himself the title of king and started a civil war by invading the Indo-Greek territory, forcing the Indo-Greeks to retreat from their easternmost possessions and establish their new oriental frontier at Mathura, to confront this new threat:

- "(But ultimately) the Yavanas, intoxicated with fighting, will not stay in Madhadesa (the Middle Country); there will be undoubtedly a civil war among them, arising in their own country (Bactria), there will be a terrible and ferocious war." (Gargi-Samhita, Yuga Purana chapter, No7).

The Hathigumpha inscription, written by the king of Kalinga, Kharavela, also describes the presence of the Greek king "Demetrius" with his army in eastern India, possibly as far as the city of Rajagriha about 70 km southeast of Pataliputra and one of the foremost Buddhist sacred cities, but claims that Demetrius ultimately retreated to Mathura on hearing of Kharavela's military successes further south:

- "Then in the eighth year, (Kharavela) with a large army having sacked Goradhagiri causes pressure on Rajagaha (Rajagriha). On account of the loud report of this act of valour, the Yavana (Greek) King Dimi retreated to Mathura having extricated his demoralized army." Epigraphia Indica, Vol. XX .

In any case, Eucratides seems to have occupied territory as far as the Indus, between ca 170 BCE and 150 BCE. His advances were ultimately checked by the Indo-Greek king Menander I (Milinda), previously a general of Demetrius, who asserted himself in the Indian part of the empire, apparently conquered Bactria as indicated by his issue of coins in the Greco-Bactrian style, and even began the last expansions eastwards.

Consolidation and rise of Menander I

Menander (Milinda) is considered as probably the most successful Indo-Greek king, and the conqueror of the vastest territory . The finds of his coins are the most numerous and the most widespread of all the Indo-Greek kings. In Antiquity, from at least the 1st century CE, the "Menander Mons", or "Mountains of Menander", came to designate the mountain chain at the extreme east of the Indian subcontinent, today's Naga hills and Arakan, as indicated in the Ptolemy world map of the 1st century CE geographer Ptolemy. Presumably the "Menander Mons" were so named because they marked the easternmost extent of his Indian conquests. Menander is also remembered in Budddhist literature (the Milinda Panha) as a convert to Buddhism: he became an arhat whose relics were enshrined in a manner reminiscent of the Buddha. He also introduced a new coin type, with Athena Alkidemos ("Protector of the people") on the reverse, which was adopted by most of his successors in the East.

Conquests east of the Punjab region were most likely made during the second half of the century by the king Menander I.

Following Menander's reign, about twenty Indo-Greek kings are known to have ruled in succession in the eastern parts of the Indo-Greek territory. Upon his death, Menander was succeeded by his queen Agathokleia, who for some time acted as regent to their son Strato I.

Greco-Bactrian encroachments

From 130 BCE, Indo-European nomads (the Scythians and then the Yuezhi, following a long migration from the border of China) started to invade Bactria from the north. Around 125 BCE the Greco-Bactrian king Heliocles, son of Eucratides, was probably killed during the invasion and the Greco-Bactrian kingdom proper ceased to exist. Heliocles may have been survived by his relative Eucratides II, who ruled south of the Hindu Kush, in areas untouched by the invasion. Other Indo-Greek kings like Zoilos I, Lysias and Antialcidas may possible have been relatives of either the Eucratid or the Euthydemid dynasties; they struck both Greek and bilingual coins and established a kingdom of their own.

A stabilizing alliance with the Yuezhi then seems to have followed, as hinted on the coins of Zoilos I, who minted coins showing Heracles' club together with a steppe-type recurve bow inside a victory wreath.

The Indo-Greeks thus suffered encroachments by the Greco-Bactrians in their western territories. The Indo-Greek territory was divided into two realms: the house of Menander retreated to their territories east of the Jhelum River as far as Mathura, whereas the Western kings ruled a larger kingdom of Paropamisadae, western Punjab and Arachosia to the south.

Culture

Buddhism flourished under the Indo-Greek kings, and it has been suggested that their invasion of India was intended to show their support for the Mauryan empire, which had a long history of marital alliances, treaties of friendship, and exchange of ambassadors and religious emissaries with the Greeks , and to protect the Buddhist faith from the religious persecutions of the Sungas .

Demetrius, who organized the invasion, was named Dharmamita ("Friend of the Dharma") in the Indian text of the Yuga-Purana. The city of Sirkap founded by Demetrius combines Greek and Indian influences without signs of segregation between the two cultures.

The first Greek coins to be minted in India, those of Menander I and Appolodotus I bear the mention "Saviour king" (BASILEOS SOTHROS), a title with high value in the Greek world which indicated an important deflective victory. For instance, Ptolemy I had been Soter (saviour) because he had helped save Rhodes from Demetrius the Besieger, and Antiochus I because he had saved Asia Minor from the Gauls .

Also, most of the coins of the Greek kings in India were bilingual, written in Greek on the front and in Pali (in the Kharoshthi script) on the back, a tremendous concession to another culture never before made in the Hellenic world. From the reign of Apollodotus II, around 80 BCE, Kharoshthi letters started to be used as mintmarks on coins in combination with Greek monograms and mintmarks, suggesting the participation of local technicians to the minting process. Incidentally, these bilingual coins of the Indo-Greeks were the key in the decipherment of the Kharoshthi script by James Prinsep (1799-1840). Kharoshthi became extinct around the 3rd century CE.

In Indian literature, the Indo-Greeks are described as Yavanas (transliteration of "Ionians"). Direct epigraphical evidence involves the Indo-Greek kings, such as the mention of the "Yavana king" Antialcidas on the Heliodorus pillar in Vidisha, or the mention of Menander I in the Buddhist text of the Milinda Panha. In the Harivamsa the "Yavana" Indo-Greeks are qualified, together with the Sakas, Kambojas, Pahlavas and Paradas as Kshatriya-pungava i.e foremost among the Warrior caste, or Kshatriyas. The Majjhima Nikaya explains that in the lands of the Yavanas and Kambojas, in contrast with the numerous Indian castes, there were only two classes of people, Aryas and Dasas (masters and slaves). The Arya could become Dasa and vice versa.

Religion

In addition to the worship of the Classical pantheon of the Greek deities found on their coins (Zeus, Herakles, Athena, Apollo...), the Indo-Greeks were involved with local faiths, particularly with Buddhism, but also with Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

Buddhism

Main article: Greco-Buddhism

The Edicts of Ashoka, inscribed during the reign of the Indian emperor Ashoka (273-232 BCE), claim that the Greek populations of the northwestern Indian subcontinent (in today's Afghanistan and ancient Gandhara) had already welcomed Buddhism by around 250 BCE:

- "Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dharma. (Edicts of Ashoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika).

After the Greco-Bactrians militarily occupied northern India from around 180 BCE, numerous instances of interaction between Greeks and Buddhism are recorded.

The conversion of Menander

Menander I, one of the most famous successors of Demetrius, ruled from 150 to 135 BCE. He is presented by Greek authors as an even greater conqueror than Alexander the Great. Strabo (XI.II.I) says Menander was one of the two Bactrian kings who extended their power farthest into India.

Menander, the "Saviour king", seems to have converted to Buddhism, and is described in Buddhist texts as a great benefactor of the religion, on a par with Ashoka or the future Kushan emperor Kanishka. He is famous for his dialogues with the Buddhist monk Nagasena, transmitted to us in the Milinda Panha, which explain that he became a Buddhist arhat:

- "And afterwards, taking delight in the wisdom of the Elder, he handed over his kingdom to his son, and abandoning the household life for the house-less state, grew great in insight, and himself attained to Arahatship!" (The Questions of King Milinda, Translation by T. W. Rhys Davids)

Upon his death, the honour of sharing his remains was claimed by the various cities under his rule, and they were enshrined in "monuments" (probably stupas), in a parallel with the historic Buddha:

- "But when one Menander, who had reigned graciously over the Bactrians, died afterwards in the camp, the cities indeed by common consent celebrated his funerals; but coming to a contest about his relics, they were difficultly at last brought to this agreement, that his ashes being distributed, everyone should carry away an equal share, and they should all erect monuments to him." (Plutarch, "Political Precepts" Praec. reip. ger. 28, 6 ).

Buddhist proselytism

During the reign of Menander, the Greek (Pali: Yona, lit: "Ionian") Buddhist monk Mahadhammarakkhita (Sanskrit: Mahadharmaraksita) is said to have come from Alasandra (thought to be Alexandria of the Caucasus, the city founded by Alexander the Great, near today's Kabul) with 30,000 monks for the foundation ceremony of the Maha Thupa ("Great stupa") at Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, indicating the importance of Buddhism within Greek communities in northwestern India, and the prominent role Greek Buddhist monks played in them:

- "From Alasanda the city of the Yonas came the thera (elder) Yona Mahadhammarakkhita with thirty thousand bhikkhus." (Mahavamsa, XXIX )

Several Buddhist dedications by Greeks in India are recorded, such as that of the Greek meridarch (civil governor of a province) named Theodorus, describing in Kharoshthi how he enshrined relics of the Buddha. The inscriptions were found on a vase inside a stupa, dated to the reign of Menander or one his successors in the 1st century BCE (Tarn, p391):

- "Theudorena meridarkhena pratithavida ime sarira sakamunisa bhagavato bahu-jana-stitiye":

- "The meridarch Theodorus has enshrined relics of Lord Shakyamuni, for the welfare of the mass of the people"

- (Swāt relic vase inscription of the Meridarkh Theodoros )

Although the spread of Buddhism to Central Asia and Northern Asia is usually associated with the Kushans, a century or two later, there is a possibility that it may have been introduced in those areas from Gandhara "even earlier, during the time of Demetrius and Menander" (Puri, "Buddhism in Central Asia").

Buddhist symbolism

From around 180 BCE, Agathocles and Pantaleon, probable successors to Demetrius I in the Paropamisadae, and the earliest Greek kings to issue Indian-standard square bilingual coins (in Brahmi), depicted the Buddhist lion together with the Hindu goddess Lakshmi. These coins show an unprecedented willingness to adapt to every aspect of the local culture: shape of the coinage, coinage size, language, and religion.

Later, some Indo-Greek coins incorporate the Buddhist symbol of the eight-spoked wheel, such as those of Menander I, as well as his probable grandson Menander II. On these coins, the wheel is associated with the Greek symbols of victory, either the palm of victory, or the victory wreath handed over by the goddess Nike.

The ubiquitous symbol of the elephant may or may not have been associated with Buddhism. Interestingly, on some coin series of Antialcidas, the elephant holds the same relationship to Zeus and Nike as the Buddhist wheel on the coin of Menander II, tending to suggest a common meaning for both symbols. Some of the earlier coins of king Apollodotus I directly associate the elephant with Buddhist symbolism, such as the stupa hill surmounted by a star, also seen, for example on the coins of the Mauryan Empire or those of the later Kuninda kingdom. Conversely, the bull is probably associated with Shiva, and often described in an erectile state as on the coins of Apollodotus I.

Also, after the reign of Menander I, several Indo-Greek rulers, such as Agathokleia, Amyntas, Nicias, Peukolaos, Hermaeus, Hippostratos and Menander II, depicted themselves or their Greek deities forming with the right hand a symbolic gesture identical to the Buddhist vitarka mudra (thumb and index joined together, with other fingers extended), which in Buddhism signifies the transmission of the Buddha's teaching.

At precisely the same time, right after the death of Menander, several Indo-Greek rulers also started to adopt on their coins the Pali title of "Dharmikasa", meaning "follower of the Dharma" (the title of the great Indian Buddhist king Ashoka was Dharmaraja "King of the Dharma" ). This usage was adopted by Strato I, Zoilos I, Heliokles II, Theophilos, Peukolaos, Menander II and Archebios.

Altogether, the conversion of Menander I to Buddhism suggested by the Milinda Panha seems to have triggered the use of Buddhist symbolism in one form or another on the coinage of close to half of the kings who succeeded him. Especially, all the kings after Menander who are recorded to have ruled in Gandhara (apart from the little known Demetrius III) display Buddhist symbolism in one form or another. On the contrary, none of the kings whose rule was limited to Punjab did display Buddhist signs (with the exception of the powerful Hippostratos, who probably took under his protection many Gandharan Greeks fleeing from the Indo-Scythians (Tarn).).

A 2nd century BCE relief from a Buddhist stupa in Bharhut, in eastern Madhya Pradesh (today at the Indian Museum in Calcutta), represents a foreign soldier with the curly hair of a Greek and the royal headband with flowing ends of a Greek king. In his left hand, he hold a branch of ivy, symbol of Dionysos. Also parts of his dress, with rows of geometrical folds, are characteristically Hellenistic in style. On his sword appears the Buddhist symbol of the three jewels, or Triratana.

Representation of the Buddha

The anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha is absent from Indo-Greek coinage, suggesting that the Indo-Greek kings may have respected the Indian aniconic rule for Buddhist depictions, limiting themselves to Buddhist symbolism only. Consistently with this perspective, the actual depiction of the Buddha would be a later phenomenon, usually dated to the 1st century CE, emerging from the sponsorship of the syncretic Kushan Empire and executed by Greek, and, later, Indian and possibly Roman artists. Datation of Greco-Buddhist statues is generally uncertain, but they are at least firmly established from the 1st century CE.

Another possibility is that the Indo-Greeks may not have considered the Buddha strictly as a God, but rather as an essentially human sage or philosopher, in line with the traditional Nikaya Buddhist doctrine. Just as philosophers were routinely represented in statues (but certainly not on coins) in Antiquity, the Indo-Greek may have initiated anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha in statuary only, possibly as soon as the 2nd-1st century BCE, as advocated by Foucher and suggested by Chinese murals depicting Emperor Wu of Han worshipping Buddha statues brought from Central Asia in 120 BCE (See picture) ). The willingness of ancient Greeks to represent local deities is also attested in Egypt with the creation of the god Serapis in Hellenistic style, an adaptation of the Egyptian god Apis. An Indo-Chinese tradition also explains that Nagasena, also known as Menander's Buddhist teacher, created in 43 BCE in the city of Pataliputra a statue of the Buddha, the Emerald Buddha, which was later brought to Thailand.

Stylistically, Indo-Greek coins generally display a very high level of Hellenistic artistic realism, which declined drastically around 50 BCE with the invasions of the Indo-Scythians, Yuezhi and Indo-Parthians. The first known statues of the Buddha are also very realistic and Hellenistic in style and are more consistent with the pre-50 BCE artistic level seen on coins. This would tend to suggest that the first statues were created between 130 BCE (death of Menander) and 50 BCE, precisely at the time when Buddhist symbolism appeared on Indo-Greek coinage. From that time, Menander and his successors may have been the key propagators of Buddhist ideas and representations: "the spread of Gandhari Buddhism may have been stimulated by Menander's royal patronage, as may have the development and spread of Gandharan sculpture, which seems to have accompanied it" (Mc Evilly, "The shape of ancient thought", p378)

The representation of the Buddha may also be connected to his progressive deification, which is usually associated with the spread of the Indian principle of Bhakti (personal devotion to a deity). Bhakti is a principle which evolved in the Bhagavata religious movement, and is said to have permeated Buddhism from about 100 BCE, and to have been a contributing factor to the representation of the Buddha in human form. The association of the Indo-Greeks with the Bhagavata movement is documented in the inscription of the Heliodorus pillar, made during the reign of the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas (r.c. 115-95 BCE). At that time relations with the Sungas seem to have improved, and some level of religious exchange seems to have occurred. The point of time when bhakti fervour would have encountered the Hellenistic artistic tradition would then be around 100 BCE.

Most of the early images of the Buddha (especially those of the standing Buddha) are anepigraphic, which makes it difficult to have a definite datation. The earliest known image of the Buddha with approximate indications on date is the Bimaran casket, which has been found buried with coins of the Indo-Scythian king Azes II (or possibly Azes I), indicating a 30-10 BCE date , although this date is not undisputed. Such datation, as well as the general Hellenistic style and attitude of the Buddha on the Bimaran casket (himation dress, contrapposto attitude, general depiction) would made it a possible Indo-Greek work, used in dedications by Indo-Scythians right after the end of Indo-Greek rule in the area of Gandhara. Since it already displays quite a sophisticated iconography (Brahma and Indra as attendants, Bodhisattvas) in an advanced style, it would suggest much earlier representations of the Buddha were already current by that time, going back to the rule of the Indo-Greeks (Alfred A. Foucher and others).

Hinduism

Obv: Bust of Agathocles.

Rev: Zeus holding sceptre, with Hecate on extended arm. Greek legend ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΟΝΤΟΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ "Under the reign of King Agathocles".

Obv: Indian god Balarama-Samkarshana. Greek legend: BASILEOS AGATOKLEOUS "Of King Agathocles".

Rev: Indian god Vasudeva-Krishna. Brahmi legend: RAJANE AGATHUKLAYASA "King Agathocles".

The first known bilingual coins of the Indo-Greeks were issued by Agathocles around 180 BCE. These coins were found in Ai-Khanoum, the great Greco-Bactrian city in northeastern Afghanistan, but introduce for the first time an Indian script (the Brahmi script which had been in use under the Mauryan empire), and the first known representations of Hindu deities, in a very Indian iconography: Krishna-Vasudeva, with his large wheel with six spokes (chakra) and conch (shanka), and his brother Samkarsa-Balarama, with his plough (hala) and pestle (masala), both early avatars of Vishnu . The square coins, instead of the usual Greek round coins, also followed the Indian standard for coinage. The dancing girls on some of the coins of Agathocles and Pantaleon are also sometimes considered as representations of Subhadra, Krishna's sister.

These first issues were in several respects a short-lived experiment. Hindu anthropomorphic deities were never again represented in Indo-Greek coinage (although the bull on the vast quantity of subsequent coins may have symbolized Shiva, as the elephant may have symbolized Buddhism), and the Brahmi script was immediately replaced by the Kharoshti script, derived from Aramaic. The general practice however of minting bilingual coins and combining Greek and Indian iconography, sometimes in the Greek and sometimes in the Indian standard continued for the next two centuries.

In any case, these coins suggest the strong presence of Indian religious traditions in the northwestern Indian subcontinent at that time, and the willingness of the Greeks to acknowledge and even promote them. Artistically, they tend to indicate that the Greeks were not particularly reluctant to make representations of local deities, which has some bearing on the later emergence of the image of the Buddha in Hellenistic style.

The Heliodorus pillar inscription is another epigraphical evidence of the interaction between Greeks and Hinduism. The pillar was erected around 110 BCE in central India at the site of Vidisha, by Heliodorus, a Greek ambassador of the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas to the court of the Sunga king Bhagabhadra. The pillar was surmounted by a sculpture of Garuda and was apparently dedicated by Heliodorus to the temple of Vasudeva.

- "This Garuda-standard of Vasudeva (Vishnu), the God of Gods

- was erected here by the Bhagavata Heliodoros,

- the son of Dion, a man of Taxila,

- sent by the Great Greek (Yona) King

- Antialkidas, as ambassador to

- King Kasiputra Bhagabhadra, the Savior

- son of the princess from Benares, in the fourteenth year of his reign."

- (Heliodorus pillar inscription)

Zoroastrianism

Persian culture and religion seem to have been rather influencial among the Western Indo-Greeks, who, located around the Paropamisadae, lived in direct contact with the Central Asian cultural sphere and the eastern reaches of the Parthian empire. Images of the Persian Zoroastrian god Mithra appear extensively on the Indo-Greek coinage of the Western kings, as a god with a radiated phrygian cap.

This Zeus-Mithra god is also the one represented seated (with the rays around the head, and a small protrusion on the top of the head representing the cap) on many coins of Hermaeus, Antialcidas or Heliokles II, or possibly even earlier during the time of Eucratides I, on whose coins the deity is said to be the god of the city of Kapisa.

The future Buddha Maitreya, usually represented seated on a throne Western-style, and venerated both in Mahayana and non-Mahayana Buddhism, is sometimes considered as influenced by the god Mithra. "Some scholars suggest he (Maitreya) was originally linked to the Iranian saviour-figure Mitra, and that his later importance for Buddhist as the future Buddha residing in the Tusita heaven, who will follow on from Sakyamuni Buddha, derives from this source." (Keown, Dictionary of Buddhism)

Art

Incipient Greco-Buddhist art

Main article: Greco-Buddhist art

In general, the art of the Indo-Greeks is poorly documented, and few works of art (apart from their coins and a few stone palettes) are directly attributed to them. Traditionally, no sculptural remains have been attributed to the Indo-Greeks, although their Hellenistic heritage and artistic proficiency would naturally have encouraged such creations (as neighbouring and contemporary Ai-Khanoum abundantly suggests). On the contrary, and rather paradoxically, most Gandharan Hellenistic works of art are usually attributed to the direct successors of the Indo-Greeks in India, such as the Indo-Scythians, the Indo-Parthians and the Kushans, from the 1st century CE.

The possibility of a direct connection between the Indo-Greeks and Greco-Buddhist art has been reaffirmed recently as the dating of the rule of Indo-Greek kings has been extended to the first decades of the 1st century CE, with the reign of Strato II in the Punjab . Also, Foucher, Tarn and more recently Boardman or McEvilley have taken the view that some of the most purely Hellenistic works of northwestern India and Afghanistan, may actually be wrongly attributed to later centuries, and instead belong to a period one or two centuries earlier, to the time of the Indo-Greeks in the 2nd-1st century BCE . This is particularly the case of some purely Hellenistic works in Hadda, Afghanistan, an area which "might indeed be the cradle of incipient Buddhist sculpture in Indo-Greek style" . Referring to one of the Buddha triads in Hadda (drawing), in which the Buddha is sided by very Classical depictions of Herakles/Vajrapani and Tyche/Hariti, Boardman explains that both figures "might at first (and even second) glance, pass as, say, from Asia Minor or Syria of the first or second century BC (...) these are essentially Greek figures, executed by artists fully conversant with far more than the externals of the Classical style" . Many of the works of art at Hadda can also be compared to the style of the 2nd century BCE sculptures of the Hellenistic world, such as those of the Temple of Olympia at Bassae in Greece, which could also suggest roughly contemporary dates.

Alternatively, it has been suggested that these works of art may have been executed by itinerant Greek artists during the time of maritime contacts with the West from the 1st to the 3rd century CE .

The supposition that such highly Hellenistic and, at the same time Buddhist, works of art belong to the Indo-Greek period would be consistent with the known Buddhist activity of the Indo-Greeks (the Milinda Panha etc...), their Hellenistic cultural heritage which would naturally have induced them to produce extensive statuary, their know artistic proficiency as seen on their coins until around 50 BCE, and the dated appearance of already complex iconography incorporating Hellenistic sculptural codes with the Bimaran casket in the early 1st century CE.

Indo-Greeks in the art of Gandhara

The Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, beyond the omnipresence of Greek style and stylistic elements which might be simply considered as an enduring artistic tradition, offers numerous depictions of people in Greek Classical realistic style, attitudes and fashion (clothes such as the chiton and the himation, similar in form and style to the 2nd century BCE Greco-Bactrian statues of Ai-Khanoum, hairstyle), holding contraptions which are characteristic of Greek culture (amphoras, "kantaros" Greek drinking cups), in situations which can range from festive (such as Bacchanalian scenes) to Buddhist-devotional.

Uncertainties in dating make it unclear whether these works of art actually depict Greeks of the period of Indo-Greek rule up to the 1st century BCE, or remaining Greek communities under the rule of the Indo-Parthians or Kushans in the 1st and 2nd century CE.

-

Greek Buddhist devotees, holding plantain leaves, in purely Hellenistic style, inside Corinthian columns, Buner relief, dated 1st-2nd century CE.

-

Bacchanalian scene, representing the harvest of wine grapes, Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, 1st-2nd century CE.

-

Drinking scene, with Dionysus and Ariadne on his lap, Greek drinking cups, Greek dress. Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara. Dated 3rd century CE.

-

"The Great Departure", with the Buddha amid Greek deities and costumes.

Economy

Very little is known about the economy of the Indo-Greeks. The abundance of their coins would tend to suggest large mining operations, particularly in the mountainous area of the Hindu-Kush, and an important monetary economy. The Indo-Greek did strike bilingual coins both in the Greek "round" standard and in the Indian "square" standard, suggesting that monetary circulation extended to all parts of society. The adoption of Indo-Greek monetary conventions by neighbouring kingdoms, such as the Kunindas to the east and the Satavahanas to the south, would also suggest that Indo-Greek coins were used extensively for cross-border trade.

Tribute payments

It would also seem that some of the coins emitted by the Indo-Greek kings, particularly those in the monolingual Attic standard, may have been used to pay some form of tribute to the Yuezhi tribes north of the Hindu-Kush. This is indicated by the coins finds of the Qunduz hoard in northern Afghanistan, which have yielded quantities of Indo-Greek coins in the Hellenistic standard (Greek weights, Greek language), although none of the kings represented in the hoard are known to have ruled so far north. Conversely, none of these coins have ever been found south of the Hindu-Kush .

Trade with China

An indirect testimony by the Chinese explorer Zhang Qian, who visited Bactria around 128 BCE, suggests that intense trade with Southern China was going through northern India, and therefore probably through the contemporary Indo-Greek realm. Zhang Qian explains that he found Chinese products in the Bactrian markets, and that they were transiting through India:

- "When I was in Bactria," Zhang Qian reported, "I saw bamboo canes from Qiong and cloth (silk?) made in the province of Shu. When I asked the people how they had gotten such articles, they replied: "Our merchants go buy them in the markets of Shendu (northwestern India). Shendu, they told me, lies several thousand li southeast of Bactria. The people cultivate land, and live much like the people of Bactria". (Sima Qian, "Records of the Great Historian", trans. Burton Watson, p236).

Indian Ocean trade

Maritime relations across the Indian ocean started in the 3rd century BCE, and further developed during the time of the Indo-Greeks together with their territorial expansion along the western coast of India. The first contacts started when the Ptolemies constructed the Red Sea ports of Myos Hormos and Berenike, with destination the Indus delta and the Kathiawar peninsula. Around 130 BCE, Eudoxus of Cyzicus is reported (Strabo, Geog. II.3.4 ) to have made a successful voyage to India and returned with a cargo of perfumes and gemstones. By the time Indo-Greek rule was ending, up to 120 ships were setting sail every year from Myos Hormos to India (Strabo Geog. II.5.12 ).

Armed forces

The coins of the Indo-Greeks provide rich clues on their uniforms and weapons. Typical Hellenistic uniforms are depicted, with helmets being either round in the Greco-Bactrian style, or the flat kausia of the Macedonians (coins of Apollodotus I).

Military technology

Their weapons were spears, swords, longbow (on the coins of Agathokleia) and arrows. Interestingly, around 130 BCE the Central Asian recurve bow of the steppes with its gorytos box starts to appear for the first time on the coins of Zoilos I, suggesting strong interactions (and apparently an alliance) with nomadic peoples, either Yuezhi or Scythian. The recurve bow becomes a standard feature of Indo-Greek horsemen by 90 BCE, as seen on some of the coins of Hermaeus.

Generally, Indo-Greek kings are often represented riding horses, as soon as the reign of Antimachus II around 160 BCE. The equestrian tradition probably goes back to the Greco-Bactrians, who are said by Polybius to have faced a Seleucid invasion in 210 BCE with 10,000 horsemen . Although war elephants are never represented on coins, a harness plate (phalera) dated to the 3-2nd century BCE, today in the Hermitage Museum, depicts a helmetted Greek combatant on an Indian war elephant, and would be either Greco-Bactrian or Indo-Greek work. Indian war elephants were a standard feature of Hellenistic armies, and this would naturally have been the case for the Indo-Greeks as well.

The Milinda Panha, in the questions of Nagasena to king Menander, provides a rare glimpse of the military methods of the period:

- "Has it ever happened to you, O king, that rival kings rose up against you as enemies and opponents?

- -Yes, certainly.

- -Then you set to work, I suppose, to have moats dug, and ramparts thrown up, and watch towers erected, and strongholds built, and stores of food collected?

- -Not at all. All that had been prepared beforehand.

- -Or you had yourself trained in the management of war elephants, and in horsemanship, and in the use of the war chariot, and in archery and fencing?

- -Not at all. I had learnt all that before.

- -But why?

- -With the object of warding off future danger."

- (Milinda Panha, Book III, Chap 7)

Size of Indo-Greek armies

The armed forces of the Indo-Greeks during their invasion of India must have been quite considerable, as suggested by their ability to topple local rulers, but also by the size of the armed reaction of some Indian rulers. The ruler of Kalinga, Kharavela, claims in the Hathigumpha inscription that he led a "large army" in the direction of Demetrius' own "army" and "transports", and that he induced him to retreat from Pataliputra to Mathura. A "large army" for the state of Kalinga must indeed have been quite considerable. The Greek ambassador Megasthenes took special note of the military strength of Kalinga in his Indica in the middle of the 3rd century BCE:

- "The royal city of the Calingae (Kalinga) is called Parthalis. Over their king 60,000 foot-soldiers, 1,000 horsemen, 700 elephants keep watch and ward in "procinct of war." (Megasthenes fragm. LVI. in Plin. Hist. Nat. VI. 21. 8-23. 11. ).

That this kind of military strength was needed to confront the Indo-Greeks is indicative of the Indo-Greeks' own military commitment.

An account by the Roman writer Justin gives another hint of the size of Indo-Greek armies, which, in the case of the conflict between the Greco-Bactrian Eucratides and the Indo-Greek Demetrius II, he numbers at 60,000 (although they allegedly lost to 300 Greco-Bactrians):

- "Eucratides led many wars with great courage, and, while weakened by them, was put under siege by Demetrius, king of the Indians. He made numerous sorties, and managed to vanquish 60,000 enemies with 300 soldiers, and thus liberated after four months, he put India under his rule" (Justin, XLI,6 )

The military strength of nomadic tribes from Central Asia (Yuezhi and Scythians) probably constituted a significant threat to the Indo-Greeks. According to Zhang Qian, the Yuezhi represented a considerable force of between 100,000 and 200,000 mounted archer warriors , with customs identical to those of the Xiongnu.

Finally, the Indo-Greek seem to have combined forces with other "invaders" during their expansion into India, since they are often referred to in combination with others (especially the Kambojas), in the Indian accounts of their invasions.

Later History

Eastern Indo-Greek territories

After around 100 BCE, Indian kings recovered the area of Mathura and Eastern Punjab east of the Ravi River, and started to mint their own coins. The Arjunayanas (area of Mathura) and Yaudheyas mention military victories on their coins ("Victory of the Arjunayanas", "Victory of the Yaudheyas"). During the 1st century BCE, the Trigartas, Audumbaras and finally the Kunindas (closest to Punjab) also started to mint their own coins, usually in a style highly reminiscent of Indo-Greek coinage.

The Western king Philoxenus briefly occupied the whole remaining Greek territory from the Paropamisadae to Western Punjab between 100 to 95 BCE, after what the territories fragmented again. The eastern kings regained their territory as far west as Arachosia.

Around 80 BCE, an Indo-Scythian king named Maues, possibly a general in the service of the Indo-Greeks, ruled for a few years in northwestern India before the Indo-Greeks again took control. King Hippostratos (65-55 BCE) seems to have been one of the most successful subsequent Indo-Greek kings until he lost to the Indo-Scythian Azes I, who established an Indo-Scythian dynasty.

Throughout the 1st century BCE, the Indo-Greeks progressively lost ground against the invasion of the Indo-Scythians. Although the Indo-Scythians clearly ruled militarily and politically, they remained surprisingly respectful of Greek and Indian cultures. Their coins were minted in Greek mints, continued using proper Greek and Kharoshthi legends, and incorporated depictions of Greek deities, particularly Zeus. The Mathura lion capital inscription attests that they adopted the Buddhist faith, as do the depictions of deities forming the vitarka mudra on their coins. Greek communities, far from being exterminated, probably persisted under Indo-Scythian rule.

The Indo-Greeks continued to rule a territory in the eastern Punjab, until the kingdom of the last Indo-Greek king Strato II was taken over by the Indo-Scythian ruler Rajuvula around 10 CE.

Western Indo-Greek territories

Around eight western Indo-Greek kings are known. The last important king was Hermaeus, who reigned until around 70 BCE; soon after his death the Yuezhi took over his areas from neighbouring Bactria. Chinese chronicles (the Hou Hanshu) actually tend to suggest that the Chinese general Wen-Chung had helped negotiate the alliance of Hermaeus with the Yuezhi, against the Indo-Scythians . When Hermaeus is depicted on his coins riding a horse, he is equipped with the recurve bow and bow-case of the steppes.

After 70 BCE, the Yuezhi became the new rulers of the Paropamisadae, and minted vast quantities of posthumous issues of Hermaeus up to around 40 CE, when they blend with the coinage of the Kushan king Kujula Kadphises. The first documented Yuezhi prince, Sapadbizes, ruled around 20 BCE, and minted in Greek and in the same style as the western Indo-Greek kings, probably depending on Greek mints and celators.

The Yuezhi expanded to the east during the 1st century CE, to found the Kushan Empire. The first Kushan emperor Kujula Kadphises ostensibly associated himself with Hermaeus on his coins, suggesting that he may have been one of his descendants by alliance, or at least wanted to claim his legacy. The Yuezhi (future Kushans) were in many ways the cultural and political heirs to the Indo-Greeks, as suggested by their adoption of the Greek culture (writing system, Greco-Buddhist art) and their claim to a lineage with the last western Indo-Greek king Hermaeus.

Enduring legacy of the Indo-Greek Kingdom

From the 1st century CE, the Greek communities of central Asia and northwestern India lived under the control of the Kushan branch of the Yuezhi, apart from a short-lived invasion of the Indo-Parthian Kingdom. The Kushans founded the Kushan Empire, which was to prosper for several centuries. In the south, the Greeks were under the rule of the Western Kshatrapas.

It is unclear how much longer the Greeks managed to maintain a distinct presence in the Indian sub-continent.

Military role

At the beginning of the 2nd century CE, the Central India Satavahana king Gautamiputra Sātakarni (r. 106–130 CE) would call himself "Destroyer of Sakas (Western Kshatrapas), Yavanas (Indo-Greeks) and Pahlavas (Indo-Parthians)" in his inscriptions, suggesting a continued presence of the Indo-Greeks until that time.

Around 200 CE, the Manu Smriti describes the downfall of the Yavanas, as well as many others:

"43. But in consequence of the omission of the sacred rites, and of their not consulting Brahmanas, the following tribes of Kshatriyas have gradually sunk in this world to the condition of Shudras;

44. (Viz.) the Paundrakas, the Chodas, the Dravidas, the Kambojas, the Yavanas, the Shakas, the Paradas, the Pahlavas, the Chinas, the Kiratas, the Daradas and the Khashas." (Manusmritti, X.43-44)

The Brihat-Katha-Manjari text of the Sanskrit poet Kshmendra (11th and 12th centuries) (10/1/285-86) relates that around 400 CE the Gupta king Vikramaditya (Chandragupta II) had "unburdened the sacred earth of the Barbarians" like "the Shakas, Mlecchas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Tusharas, Parasikas, Hunas" etc… by annihilating these "sinners" completely.

Linguistic legacy

A few common Greek words were adopted in Sanskrit, such as words related to writing:

- "ink" (Sankrit: melā, Greek: μέλαν "melan")

- "pen" (Sanskrit:kalamo, Greek:κάλαμος "kalamos")

- "book" (Sankrit: pustaka, Greek: πύξινον "puksinon")

There are also a few words related to warfare:

- a "horse's bit" (Sanskrit: khalina, Greek: χαλινός "khalinos")

- a "siege mine" (used to undermine the wall of a fortress): (Sanskrit: surungā, Greek: σύριγγα "suringa")

From the inscription of Rabatak we have the following information, tending to indicate that Greek was in official use until the time of Kanishka (circa 120 CE):

- "He (Kanishka) issued(?) an edict(?) in Greek and then he put it into the Aryan language". …but when Kanishka refers to "the Aryan language" he surely means Bactrian, …"By the grace of Auramazda, I made another text in Aryan, which previously did not exist". It is difficult not to associate Kanishka's emphasis here on the use of the "Aryan language" with the replacement of Greek by Bactrian on his coinage. The numismatic evidence shows that this must have taken place very early in Kanishka's reign,…" — Prof. Nicholas Sims-Williams (University of London).

The Greek language was probably still "alive" during the time of Kanishka, as this king introduced a new title in Greek on his early coins (BACIΛEΥC BACIΛEWΝ, "King of Kings" in the nominative), as well as the name of Greek deities such as HΛIOC (Sun god Helios), HΦAHCTOC (Fire god Hephaistos), and CAΛHNH (Moon goddess Selene).

The Greek script was used not only on coins, but also in manuscripts and stone inscriptions as late as the period of Islamic invasions in the 7th-8th century.

Astronomy

The earliest Indian writing on astronomy, the "Yavanajataka" or "Saying of the Greeks", is a translation from Greek to Sanskrit made by "Yavanesvara" ("Lord of the Greeks") in 149–150 CE under the rule of the Western Kshatrapa king Rudrakarman I.

Indian astronomy is widely acknowledged to be derived from the Alexandrian school, and its technical nomenclature is essentially Greek: "The Yavanas are barbarians, yet the science of astronomy originated with them and for this they must be reverenced like gods" (The Gargi-Samhita).

Influence of Indo-Greek coinage

Overall, the coinage of the Indo-Greeks remained extremely influencial for several centuries throughout the Indian subcontinent:

- The Indo-Greek weight and size standard for silver drachms was adopted by the contemporary Buddhist kingdom of the Kunindas in Punjab, the first attempt by an Indian kingdom to produce coins that could compare with those of the Indo-Greeks.

- In central India, the Satavahanas (2nd century BCE- 2nd century CE) adopted the practice of representing their kings in profile, within circular legends.

- The direct successors of the Indo-Greeks in the northwest, the Indo-Scythians and Indo-Parthians continued displaying their kings within a legend in Greek, and on the obverse Greek deities.

- To the south, the Western Kshatrapas (1st-4th century CE) represented their kings in profile with circular legends in corrupted Greek.

- The Kushans (1st-4th century CE) used the Greek language on their coinage until the first few years of the reign of Kanishka, whence they adopted the Bactrian language, written with the Greek script.

- The Guptas (4th-6th century CE), in turn imitating the Western Kshatrapas, also showed their rulers in profile, within a legend in corrupted Greek, in the coinage of their western territories.

The latest use of the Greek script on coins corresponds to the rule of the Turkish Shahi of Kabul, around 850 CE. As late as the 13th century, the Sultan of Delhi Mohammad I (1295-1315), one of the first Muslim rulers of northern India, would use on his coins the title Sikander el-sani ("The second Alexander"), in a reference to his famous predecessor in the conquest of India .

Genetic contribution

Limited population genetics studies have been made on genetic markers such as mitochondrial DNA in the populations of the Indian subcontinent, to estimate the contribution of the Greeks to the genetic pool. Although some of the markers which are present in a large proportion of Greeks today have not been found, the Greek/European genetic contribution to the Punjab region has been estimated between 0%–15%:

"The political influence of Seleucid and Bactrian dynastic Greeks over northwest India, for example, persisted for several centuries after the invasion of the army of Alexander the Great (Tarn 1951). However, we have not found, in Punjab or anywhere else in India, Y chromosomes with the M170 or M35 mutations that together account for 30% in Greeks and Macedonians today (Semino et al. 2000). Given the sample size of 325 Indian Y chromosomes examined, however, it can be said that the Greek homeland (or European, more generally, where these markers are spread) contribution has been 0%–3% for the total population or 0%–15% for Punjab in particular. Such broad estimates are preliminary, at best. It will take larger sample sizes, more populations, and increased molecular resolution to determine the likely modest impact of historic gene flows to India on its pre-existing large populations." (Kivisild et al. "Origins of Indian Casts and Tribes" ).

Some pockets of Greek populations probably remained for some time, and to this day, some communities in the Hindu Kush claim to be descendants of the Greeks, such as the Kalasha and Hunza in Pakistan, and the neighbouring Nuristani in Afghanistan.

One can not assume however that the present Greek population is representative of the Macedonian army under Alexander. This army probably contained a large number of Persians and other groups such as Scythians and Thracians.

Greco-Roman exchanges with India

Although the political power of the Greeks had waned in the north, mainly due to nomadic invasions, trade relations between the Mediterranean and India continued for several centuries. The trade started by Eudoxus of Cyzicus in 130 BCE kept on increasing, and according to Strabo (II.5.12), by the time of Augustus, up to 120 ships were setting sail every year from Myos Hormos to India. So much gold was used for this trade, and apparently recycled by the Kushans for their own coinage, that Pliny (NH VI.101) complained about the drain of specie to India. In practice, this trade was still handled by Greek middlemen, as all the recorded names of ship captains for the period are Greek.

In India, the ports of Barbaricum (where Karachi stands today), Barygaza, and Muziris and Arikamedu on the southern tip of India were the main centers of this trade. Ptolemy described Muzuris as "a port packed with Greek ships" (VII.I.8), and the Tamil Sangam describes that "fine vessels, masterpieces of Yavana workmanship, arrive with gold and depart with pepper". In the south, the main trading partners were the Tamil dynasties of the Pandyas, Cholas and Cheras. The 2nd century Periplus of the Erythraean Sea describes Greco-Roman merchants selling in Barbaricum "thin clothing, figured linens, topaz, coral, storax, frankincense, vessels of glass, silver and gold plate, and a little wine" in exchange for "costus, bdellium, lycium, nard, turquoise, lapis lazuli, Seric skins, cotton cloth, silk yarn, and indigo". In Barygaza, they would buy wheat, rice, sesame oil, cotton and cloth. At Cape Comorin and in Sri Lanka, they would buy pearls and gems.

Also various exchanges are recorded between India and Rome during this period. In particular, embassies from India, as well as several missions from "Sramanas" to the Roman emperors are known (see Buddhism and the Roman world). Finally, Roman goods and works of art found their way to the Kushans, as archaeological finds in Begram have confirmed.

Artistic legacy

The "Kanishka casket", dated to the first year of Kanishka's reign in 127 CE, was signed by a Greek artist named Agesilas, who oversaw work at Kanishka's stupas (caitya), confirming the direct involvement of Greeks with Buddhist realizations at such a late date.

1) Herakles (Louvre Museum).

2) Herakles on coin of Greco-Bactrian king Demetrius I.

3) Vajrapani, the protector of the Buddha, depicted as Herakles in the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara.

4) Shukongōshin, manifestation of Vajrapani, as protector deity of Buddhist temples in Japan.

Left: Greek Wind God from Hadda, 2nd century.

Middle: Wind God from Kizil, Tarim Basin, 7th century.

Right: Japanese Wind God Fujin, 17th century.

Greek representations and artistic styles, with some possible admixtures from the Roman world, continued to maintain a strong identity down to the 3rd–4th century, as indicated by the archaeological remains of such sites as Hadda in eastern Afghanistan.

The Greco-Buddhist image of the Buddha was transmitted progressively through Central Asia and China until it reached Japan in the 6th century .

Numerous elements of Greek mythology and iconography, introduced in northwestern India by the Indo-Greeks through their coinage at the very least, were then adopted throughout Asia within a Buddhist context, especially along the Silk Road. The Japanese Buddhist deity Shukongoshin, one of the wrath-filled protector deities of Buddhist temples in Japan, is an interesting case of transmission of the image of the famous Greek god Herakles to the Far-East along the Silk Road. The image of Herakles was introduced in India with the coinage of Demetrius and several of his successors, used in Greco-Buddhist art to represent Vajrapani the protector of the Buddha, and was then used in Central Asia, China and Japan to depict the protector gods of Buddhist temples .

Another case of artistic transmission is the Greek Wind God Boreas, transiting through Central Asia and China to become the Japanese Shinto wind god Fujin . In consistency with Greek iconography for Boreas, the Japanese wind god holds above his head with his two hands a draping or "wind bag" in the same general attitude. The abundance of hair have been kept in the Japanese rendering, as well as exaggerated facial features.

List of the Indo-Greek kings and their territories

Today 36 Indo-Greek kings are known. Several of them are also recorded in Western and Indian historical sources, but the majority are known through numismatic evidence only. The exact chronology and sequencing of their rule is still a matter of scholarly inquiry, with adjustments regular being made with new analysis and coin finds (overstrikes of one king over another's coins being the most critical element in establishing chronological sequences).

References

- "Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné", Osmund Bopearachchi, 1991, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, ISBN 2717718257 (French).

- "The Shape of Ancient Thought. Comparative studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies" by Thomas McEvilley (Allworth Press and the School of Visual Arts, 2002) ISBN 1581152035

- "Buddhism in Central Asia" by B.N. Puri (Motilal Banarsidass Pub, January 1, 2000) ISBN 8120803728

- "The Greeks in Bactria and India", W.W. Tarn, Cambridge University Press.

- "Dictionary of Buddhism" Damien Keown, Oxford University Press ISBN 0198605609

- "De l'Indus à l'Oxus, Archéologie de l'Asie Centrale", Osmund Bopearachchi, Christine Sachs, ISBN 2951667922 (French).

- "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity" by John Boardman (Princeton University Press, 1994) ISBN 0691036802

- "The Crossroads of Asia. Transformation in Image and symbol", 1992, ISBN 0951839918

- "Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian institution", Smithsonian Institution, Bopearachchi, 1993

- "Alexander the Great: East-West Cultural contacts from Greece to Japan" (NHK and Tokyo National Museum, 2003)

Notes

- ("Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian institution", Bopearachchi, p16).

- The Mālavikāgnimitra, a play by Kālidāsa describes a battle between Greek forces and Vasumitra, the grandson of Pushyamitra, during the later's reign. ("Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian institution", Bopearachchi, p16)

- Strabo on the extent of the conquests of the Greco-Bactrians/Indo-Greeks: "The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of Ariana, but also of India, as Apollodorus of Artemita says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander -- by Menander in particular (at least if he actually crossed the Hypanis towards the east and advanced as far as the Imaüs), for some were subdued by him personally and others by Demetrius, the son of Euthydemus the king of the Bactrians; and they took possession, not only of Patalena, but also, on the rest of the coast, of what is called the kingdom of Saraostus and Sigerdis. In short, Apollodorus says that Bactriana is the ornament of Ariana as a whole; and, more than that, they extended their empire even as far as the Seres and the Phryni." (Strabo 11.11.1 Full text)

- Full text of the Hathigumpta inscription

- "Numismats and historians are unanimous in considering that Menander was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, and the most famous of the Indo-Greek kings. The coins to the name of Menander are incomparably more abundant than those of any other Indo-Greek king" Bopearachchi, "Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques", p76.

- 1) Discussion on the dynastic alliance in Tarn, p152-153: "It has been recently suggested that Asoka was grandson of the Seleucid princess, whom Seleucus gave in marriage to Chandragupta. Should this far-reaching suggestion be well founded, it would not only throw light on the good relations between the Seleucid and Maurya dynasties, but would mean that the Maurya dynasty was descended from, or anyhow connected with, Seleucus... when the Mauryan line became extinct, he (Demetrius) may well have regarded himself, if not as the next heir, at any rate as the heir nearest at hand". 2) Description of the 302 BCE marital alliance in Strabo 15.2.1(9): "The Indians occupy some of the countries situated along the Indus, which formerly belonged to the Persians: Alexander deprived the Ariani of them, and established there settlements of his own. But Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus in consequence of a marriage contract, and received in return five hundred elephants." The ambassador Megasthenes was also sent to the Mauryan court on this occasion. 3) In the Edicts of Ashoka, king Ashoka claims to have sent Buddhist emissaries to the Hellenistic west around 250 BCE. 4) When Antiochos III, after having made peace with Euthydemus, went to India in 209 BCE, he is said to have renewed his friendship with the Indian king there: "He crossed the Caucasus (Hindu Kush) and descended into India; renewed his friendship with Sophagasenus the king of the Indians; received more elephants, until he had a hundred and fifty altogether; and having once more provisioned his troops, set out again personally with his army" Polybius 11.39

- "We can now, I think, see what the Greek 'conquest' meant and how the Greeks were able to traverse such extraordinary distances. To parts of India, perhaps to large parts, they came, not as conquerors, but as friends or 'saviors'; to the Buddhist world in particular they appeared to be its champions" (Tarn, p180)

- Tarn p175. Also: "The people to be 'saved' were in fact usually Buddhists, and the common enimity of Greek and Buddhists to the Sunga king threw them into each other's arms", Tarn p175. "Menander was coming to save them from the oppression of the Sunga kings",Tarn p178

- Bopearachchi p.138

- Plutarch "Political precepts", p147-148 Full text

- Chapter XXIX of the Mahavamsa: Text

- Original text of the inscription, in Gandhari: Text

- "Crossroads of Asia", p12

- "In the art of Gandhara, the first known image of the standing Buddha and approximatively dated, is that of the Bimaran reliquary, which specialists attribute to the Indo-Scythian period, more particularly to the rule of Azes II" (Christine Sachs, "De l'Indus à l'Oxus").

- The Crossroads of Asia, p62

- "The survival into the 1st century AD of a Greek administration and presumably some elements of Greek culture in the Punjab has now to be taken into account in any discussion of the role of Greek influence in the development of Gandharan sculpture", The Crossroads of Asia, p14

- ."The beginnings of the Gandhara school have been dated everywhere from the first century B.C. (which was M.Foucher's view) to the Kushan period and even after it" (Tarn, p394). Foucher's views can be found in "La vieille route de l'Inde, de Bactres a Taxila", pp340-341). The view is also supported by Sir John Marshall ("The Buddhist art of Gandhara", pp5-6). Also the recent discoveries at Ai-Khanoum confirm that "Gandharan art descended directly from Hellenized Bactrian art" (Chaibi Nustamandy, "Crossroads of Asia", 1992). On the Indo-Greeks and Greco-Buddhist art: "It was about this time (100 BCE) that something took place which is without parallel in Hellenistic history: Greeks of themselves placed their artistic skill at the service of a foreign religion, and created for it a new form of expression in art" (Tarn, p393). "We have to look for the beginnings of Gandharan Buddhist art in the residual Indo-Greek tradition, and in the early Buddhist stone sculpture to the South (Bharhut etc...)" (Boardman, 1993, p124). "Depending on how the dates are worked out, the spread of Gandhari Buddhism to the north may have been stimulated by Menander's royal patronage, as may the development and spread of the Gandharan sculpture, which seems to have accompanied it" McEvilley, 2002, "The shape of ancient thought", p378.

- Boardman, p141

- Boardman, p143

- "Others, dating the work to the first two centuries A.D., after the waning of Greek autonomy on the Northwest, connect it instead with the Roman Imperial trade, which was just then getting a foothold at sites like Barbaricum at the Indus-mouth. It has been proposed that one of the embassies from Indian kings to Roman emperors may have brought back a master sculptorto oversee work in the emerging Mahayana Buddhist sensibility (in which the Buddha came to be seen as a kind of deity), and that "bands of foreign workmen from the eastern centers of the Roman Empire" were brought to India" (Mc Evilley "The shape of ancient thought", quoting Benjamin Rowland "The art and architecture of India" p121 and A.C. Soper "The Roman Style in Gandhara" American Journal of Archaeology 55 (1951) pp301-319)

- Fussman, JA 1993, p127 and Bopearachchi, "Graeco-Bactrian issues of the later Indo-Greek kings", Num.Chron.1990, pp79-104)

- Strabo II.3.4‑5 on Eudoxus

- "Since the merchants of Alexandria are already sailing with fleets by way of the Nile and of the Arabian Gulf as far as India, these regions also have become far better known to us of today than to our predecessors. At any rate, when Gallus was prefect of Egypt, I accompanied him and ascended the Nile as far as Syene and the frontiers of Ethiopia, and I learned that as many as one hundred and twenty vessels were sailing from Myos Hormos of India, whereas formerly, under the Ptolemies, only a very few ventured to undertake the voyage and to carry on traffic in Indian merchandise." Strabo II.5.12

- Polybius 10.49, Battle of the Arius

- Megasthenes Indica

- Justin XLI

- "They are a nation of nomads, moving from place to place with their herds, and their customs are like those of the Xiongnu. They have some 100,000 or 200,000 archer warriors... The Yuezhi originally lived in the area between the Qilian or Heavenly mountains and Dunhuang, but after they were defeated by the Xiongnu they moved far away to the west, beyond Dayuan, where they attacked and conquered the people of Daxia (Bactria) and set up the court of their king on the northern bank of the Gui (Oxus) river" ("Records of the Great Historian", Sima Qian, trans. Burton Watson, p234)

- Following the embassy of Zhang Qian in Central Asia around 126 BCE, from around 110 BCE "more and more envoys (from China) were sent to Anxi (Parthia), Yancai, Lixuan, Tiazhi, and Shendu (India)... The largest embassies to foreign states numbered several hundred person, while even the smaller parties included over 100 members" ("Records of the Grand Historian", by Sima Qian, trans. Robert Watson, p240-241). According to the Hou Hanshu, W'ou-Ti-Lao (Spalirises), king of Ki-pin (Kophen, upper Kabul valley), killed some Chinese envoys. After the death of the king, his son (Spaladagames) sent an envoy to China with gifts. The Chinese general Wen-Chung, commander of the border area in western Gansu, accompanied the escort back. W'ou-Ti-Lao's son formented to kill Wen-Chung. When Wen-Chung discovered the plot, he allied himself with Yin-Mo-Fu (Hermaeus), "son of the king of Yung-Kiu" (Yonaka, the Greeks). They attacked Ki-Pin (possibly with the support of the Yuezhi, themselves allies of the Chinese since around 100 BCE according to the Hou Hanshu) and killed W'ou-Ti-Lao's son. Yin-Mo-Fu (Hermaeus) was then installed as king of Ki-Pin, as a vassal of the Chinese Empire, and receiving the Chinese seal and ribbon of investiture. Later Yin-Mo-Fu (Hermaeus) himself is recorded to have killed Chinese envoys in the reign of Emperor Yuan-ti (48-33 BCE), then sent envoys to apologize to the Chinese court, but he was disregarded. During the reign of Emperor Ching-ti (51-7 BCE) other envoys were sent, but they were rejected as simple traders. (Tarn, "The Greeks in Bactria and India")

- "Crossroads of Asia", p10

- Greek impact on the genetics of India (last paragraph):Text

- "Needless to say, the influence of Greek art on Japanese Buddhist art, via the Buddhist art of Gandhara and India, was already partly known in, for example, the comparison of the wavy drapery of the Buddha images, in what was, originally, a typical Greek style" (Katsumi Tanabe, "Alexander the Great, East-West cultural contacts from Greece to Japan", p19)

- "The origin of the image of Vajrapani should be explained. This deity is the protector and guide of the Buddha Sakyamuni. His image was modelled after that of Hercules. (...) The Gandharan Vajrapani was transformed in Central Asia and China and afterwards transmitted to Japan, where it exerted stylistic influences on the wrestler-like statues of the Guardian Deities (Nio)." (Katsumi Tanabe, "Alexander the Great, East-West cultural contacts from Greece to Japan", p23)

- "The Japanese wind god images do not belong to a separate tradition apart from that of their Western counter-parts but share the same origins. (...) One of the characteristics of these Far Eastern wind god images is the wind bag held by this god with both hands, the origin of which can be traced back to the shawl or mantle worn by Boreas/ Oado." (Katsumi Tanabe, "Alexander the Great, East-West cultural contacts from Greece to Japan", p21)

See also

- Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

- Seleucid Empire

- Greco-Buddhism

- Indo-Scythians

- Indo-Parthian Kingdom

- Kushan Empire

- Roman commerce

- Timeline of Indo-Greek Kingdoms

| Middle kingdoms of India | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

External links

- Indo-Greek history and coins

- Ancient coinage of the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms

- Text of Prof. Nicholas Sims-Williams (University of London) mentioning the arrival of the Kushans and the replacement of Greek Language.

- Wargame reconstitution of Indo-Greek armies