This is an old revision of this page, as edited by SyedNaqvi90 (talk | contribs) at 17:26, 27 February 2011. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:26, 27 February 2011 by SyedNaqvi90 (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Ethnic group         Notable British people of Pakistani descent:

Notable British people of Pakistani descent:James Caan, Sajid Mahmood, Natasha Khan, Tarique Ghaffur, Sayeeda Warsi, Hanif Kureishi, Tariq Ali, Amir Khan, Salma Yaqoob | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Regions: West Midlands, Greater London, Yorkshire and The Humber, North West England, Scotland Metropolitan Areas: Greater London, Birmingham Metro Area, Greater Manchester, Leeds-Bradford, Greater Glasgow Cities and towns: Batley, Birmingham, Blackburn, Bolton, Bradford, Burnley, Bury, Cardiff, Coventry, Derby, Glasgow, Huddersfield, London, Luton, Manchester, Nelson, Nottingham, Oldham, Peterborough, Preston, Reading, Rochdale, Slough, Stoke-on-Trent, Walsall | |

| Languages | |

| English (British and Pakistani) · Urdu · Kashmiri / Potwari · Punjabi · others | |

| Religion | |

| Majority Islam (92% in England and Wales) Minority Christianity (1% in England and Wales) · Irreligion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Overseas Pakistani, British Asian |

British Pakistanis (also known as Pakistani Britons) are British citizens born in, or with ancestry in Pakistan. The majority of British Pakistanis are from the Punjab and Kashmir regions, with a small number from the Pashtun provinces. The United Kingdom has the largest Pakistani diasporic community, who make up a significant proportion of British Asians.

Immigration from the region which is now Pakistan began in the mid-seventeenth century. During the two world wars, people from this region served as soldiers and in defense plants. Following World War II and the break-up of the British Empire, Pakistani migration to the United Kingdom increased; specifically during the 1950s and 1960s. Migration to the UK was made easier because Pakistan was a part of the Commonwealth. Pakistani immigration helped to resolve labour shortages in the British steel and textile industries. Doctors from Pakistan were recruited by the National Health Service in the 1960s.

The demographic of British Pakistanis has changed considerbly since they first arrived to the UK. The population has grown from about 10,000 in 1951 to roughly 1.2 million today. The most diverse Pakistani population is in London and is made up of Punjabis, Pathans, Kashmiris, Sindhis and other Urdu speakers. The majority of British Pakistanis are Muslims. Around 90 per cent of those living in England and Wales at the time of the 2001 UK Census, stated their religion as Islam. The majority are Sunni Muslims, with a significant minority of Shia Muslims. The UK also has one of the largest overseas Christian Pakistani communities and the 2001 census recorded around 8,000 Christian Pakistanis living in England and Wales.

British Pakistanis have the second highest relative poverty rate in Britain, second only to British Bangladeshis. This has not prevented a number of British Pakistanis establishing highly successful businesses. A large number of British Pakistanis are self employed, with a significant proportion working as taxi drivers or in family-run businesses in various sectors of the economy; particularly the retail sector.

History

| Part of a series on |

| British Pakistanis |

|---|

| History |

| Demographics |

| Languages |

|

| Culture |

| Religion |

| Notables |

| Related topics |

Pre-partition

Imigration from what is now Pakistan to the United Kingdom began long before the Partition of India in 1947. Muslim immigrants from the Kashmir and Sindh arrived in the British Isles as early as the mid-seventeenth century, typically as lashkars (lascars) and sailors in British port cities. These immigrants were often the first Asians to be seen in British port cities and were treated as subjects of curiosity. Despite this, most early Pakistani immigrants married local White British women because there were few south Asian women in Britain at the time. Other early Pakistanis came to the UK as scholars and stayed for study at major British institutions, before later returning to British India. An example of such a person is Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah came to the UK in 1892 and started an apprenticeship at Graham's Shipping and Trading Company. After completing his apprenticeship, Jinnah joined Lincoln's Inn, where he trained as a barrister. At 19 years old, Jinnah became the youngest Indian to be called to the bar in Britain.

British interwar period

Most of these early Pakistani settlers and their children moved from port towns to the Midlands, as Britain declared war on Germany in 1939. Many of these Kashmiris and Sindhis worked in the munition factories of Birmingham. After the war, most of these early settlers stayed on in the region and took advantage of an increase in the number of jobs.

There were 832,500 Muslim Indian soldiers in 1945, most of these recruits came from what is now Pakistan. These soldiers fought alongside the British Army during World War I and World War II, particularly in the latter, during the Battle of France, the North African Campaign and the Burma Campaign. Many contributed to the war effort as skilled workers, including as assembly-line workers in the aircraft factory at Castle Bromwich, Birmingham which produced Spitfire fighters. Most of the now Pakistani soldiers returned to the subcontinent after their service and the majority did not immediately settle in the UK, although many of these former soldiers returned to Britain in the 1950s and 1960s to fill labour shortages.

Post-partition

Following World War II and the break-up of the British Empire, Pakistani migration to the United Kingdom increased; specifically during the 1950s and 1960s. Migration to the UK was made easier because Pakistan was a part of the Commonwealth of Nations. Pakistanis were invited by employers to fill labour shortages which arose after World War II. As Commonwealth citizens, Pakistanis were eligible to take part in most British civic rights. Pakistanis found employment in the textile industries of Yorkshire and Lancashire, manufacturing in the West Midlands and in the car production and food processing industries of Luton and Slough. It was common for Pakistani employees to work on night shifts and at other unsociable hours.

Many Kashmiris began emigrating from Pakistan after the completion of Mangla Dam in Mirpur in the late 1950s. The completion of the dam led to the destruction of hundreds of villages and stimulated a large wave of migration. Up to 5,000 people from Mirpur (5 per cent of the displaced) left for Britain, the displaced Kashmiris were given legal and financial assistance by the British contractor which had built the dam. Those from unaffected areas of Pakistan, such as the Punjab, also immigrated to Britain to help fill labour shortages. Workers from the Punjab region began to leave Pakistan in the 1960s, they worked in the foundries of the English Midlands and a large number also worked at Heathrow Airport in West London.

Apart from those who came from rural areas, a considerable number of Pakistanis also arrived from urban areas in the 1960s. Many of these were qualified teachers, doctors, and engineers. According they had a predisposition to settle in London due to greater economic opportunities, when compared to the Midlands or the north of England. Most medical staff from Pakistan were recruited in the 1960s and almost all of these medical professionals worked for the National Health Service.

During the 1970s a large number of East African Asians, most of whom already held British passports because they were brought to Africa by British colonialists, entered the UK after they left Kenya and Uganda. Idi Amin chose to expell all Ugandan Asians in 1972 because of the perception that they were responsible for economic stagnation in the country. The Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 and Immigration Act 1971 largely restricted any further primary immigration to the UK, although family members of already-settled migrants were allowed to join their relatives.

When the UK experienced deindustrialisation in the 1970s, many British Pakistanis became unemployed. The change from the manufacturing sector to the service sector was difficult for ethnic minorities and White Britons alike, especially for those with little academic education. The Midlands and north of England were areas which were heavily reliant on manufacturing industries and the effects of deindustrialisation continue to be felt in these areas. As a result, increasing numbers of British Pakistanis have resorted to self-employment. National statistics from 2004 show that one in seven British Pakistani men work as taxi drivers, cab drivers or chauffeurs.

Demographics

Population

The 2001 UK Census recorded 747,285 residents who described their ethnicity as Pakistani, regardless of their birthplace. Of those Pakistanis living in England, Wales, and Scotland, 55 per cent were born in the UK, with 36.9 per cent born in Pakistan and 3.5 per cent elsewhere in Asia. According to estimates by the Office for National Statistics, the number of people born in Pakistan living in the UK in 2009 was 441,000. The Ministry of Overseas Pakistanis of the Pakistan government estimates that 1.2 million Pakistanis live in the UK; around half of the total number in Europe as a whole.

The majority of British Pakistanis are from the Kashmir and Punjab areas of Pakistan. Kashmiris make up the largest proportion of the British Pakistani population. Large Kashmiri communities can be found in Birmingham, Bradford, Oldham, and the surrounding northern towns. Luton and Slough have the largest Kashmiri communities in the south of England with a large proportion of Punjabis also living in the south. There is a small Pakistani Pashtun population in the UK. The Pakistani community of London is made up of the most diverse cohort Pakistanis.

Demographer Ceri Peach has estimated the number of British Pakistanis in the 1951 to 1991 censuses. He back-projected the ethnic composition of the 2001 census to the estimated minority populations during previous census years. The results are as follows:

| Year | Population (rounded to nearest 1,000) |

|---|---|

| 1951 (estimate) | 10,000 |

| 1961 (estimate) | 25,000 |

| 1971 (estimate) | 119,000 |

| 1981 (estimate) | 296,000 |

| 1991 (estimate) | 477,000 |

| 2001 (actual) | 747,000 |

Population distribution

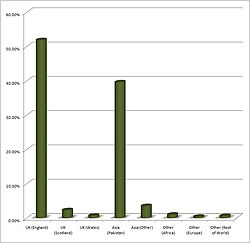

At the time of the 2001 UK Census, the distribution of people describing their ethnicity as Pakistani was as follows:

| Region | Percentage of total British Pakistani population | British Pakistanis as percentage of region's population |

|---|---|---|

| North East England | 1.88% | 0.56% |

| North West England | 15.65% | 1.74% |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 19.58% | 2.95% |

| East Midlands | 3.72% | 0.67% |

| West Midlands | 20.68% | 2.93% |

| East of England | 5.19% | 0.72% |

| London | 19.10% | 1.99% |

| South East England | 7.83% | 0.73% |

| South West England | 0.90% | 0.14% |

| Wales | 1.11% | 0.29% |

| Scotland | 4.25% | 0.63% |

| Northern Ireland | 0.09% | 0.04 |

| Total UK | 100% | 1.27% |

London

Main article: Pakistani community of LondonThe 2001 UK Census recorded 142,749 British Pakistanis living in the Greater London area. This population is made up of Punjabis, Pathans, Balochis, Sindhis and other Urdu Speakers. This mix makes the British Pakistani community of London more diverse than other Pakistani communities in the UK, this is because a high proportion of Pakistani communities in the West Midlands and the North originate from Kashmir.

The largest concentrations are in the East London communities of Ilford, Walthamstow, Leyton and Barking Other large communities can be found in Harrow, Brent, Ealing and Hounslow in West London and Wandsworth and Croydon in South London. A considerable number of Pakistanis have set up their own businesses, often employing family members. Today a fifth of Pakistani Londoners are self-employed. Businesses such as grocery stores and newsagents are common, while others who arrived later commonly work as taxi drivers or chauffeurs. Well-known British Pakistanis from London include Anwar Pervez, whose Earl's Court grocery store expanded into the Bestway chain with a turnover of £2 billion and the playwright and author Hanif Kureishi.

Birmingham

Birmingham has one of the largest Pakistani communities not only in the UK but also globally (113,000 Pakistanis made up 11.2 per cent of the city's population in 2007). The largest concentrations are in inner city Birmingham and areas such as Alum Rock and Balsall Heath, there is also a large Bangladeshi community who live in some of these areas. Most "Brummie" Pakistanis can trace their roots to Kashmir and Punjab, but Pashtun people of Afghan origin have also, in more recent times, moved to Birmingham as refugees who have fled from conflicts in Afghanistan. There is also an Iranian community in Birmingham, this is notable because there are some significant Pashtun tribes who live in Iran. These different cultures add to the diversity which is often associated with Birmingham.

Bradford

Bradford is famous for its large Pakistani population and is often dubbed Bradistan. The majority of Pakistanis in Bradford can trace their roots to the Mirpur District of Kashmir. Mirpur is considered to be a rural and conservative area of Pakistan. In 2001, riots escalated between the city's majority white population and its visible ethnic minorities (mostly Pakistani), the disturbances were known as the Bradford Riots. The riots were estimated to have involved 1,000 youths. More than 300 police officers were hurt during the riot. There were 297 arrests in total; 187 people were charged with riot, 45 with violent disorder and 200 jail sentences totalling 604 years were handed down. In 2007, it was estimated that 80,000 Pakistanis lived in Bradford, representing 16.1 per cent of the city's population.

Glasgow

Pakistanis make up the largest ethnic minority group in Scotland, representing nearly one third of the minority ethnic population in Scotland. There are an estimated 20,000 Pakistanis living in Glasgow. There are large Pakistani communities throughout the city, notably in the Pollokshields area of South Glasgow, where there is said to be some "high standard" Pakistani takeaways and Asian fabric shops. The majority have origins from the central Punjab part of Pakistan, including Faisalabad and Lahore. A survey by the University of Glasgow found that Scottish Pakistanis feel more patriotic than English people. The survey also revealed Scottish Pakistanis preferred political party to be the SNP. There is also a Pakistani Church of Scotland minister who is based in Glasgow.

Manchester

Pakistanis are the largest visible minority in Manchester, where they made up 3.8 per cent of the city's population in 2001. Large Pakistani populations are also to be found in the Greater Manchester boroughs of Oldham and Rochdale, where they make up 4.1 per cent and 5.5 per cent of the populations respectively. With greater prosperity, a recent trend has seen some of Manchester's Asian community move out of the inner city into more spacious suburbs. A significant number of Asian business families have moved down the A34 road to live in the affluent Heald Green area. Heald Green and the neighbouring Cheadle Hulme area is also said to have a growing Muslim community.

Religion

The majority of Pakistanis in the UK are Muslims. The largest proportion of these Muslims belong to the Sunni branch of Islam with a significant minority belonging to the Shia branch. Pakistanis account for 42.7 per cent of all Muslims in England. This figure varies from a high of 71 per cent in Yorkshire and The Humber to a low of 21.5 per cent in Greater London. In England and Wales, there are around 8,000 Pakistani Christians, and slightly fewer Hindus and Sikhs. The overall religious breakdown of British Pakistanis living in England and Wales in 2001 can be seen below:

| Religion | Percentage of British Pakistani population in England and Wales |

|---|---|

| 92.01% | |

| Not Stated | 6.16% |

| 1.09% | |

| Agnostic | 0.50% |

| 0.08% | |

| 0.05% | |

| 0.05% | |

| Other Religion | 0.04% |

| 0.03% | |

| Total | 100% |

Languages

Most British Pakistanis speak English and those who were born in the UK would consider English to be their first language. Urdu is understood and spoken by many British Pakistanis, due to its status as an official language in Pakistan. Urdu is offered in madrassas along with Arabic. It is also taught in some secondary schools and colleges for GCSEs and A Levels. As the majority of Pakistanis in Britain are from Kashmir and Punjab, some common languages spoken amongst Pakistanis in Britain are Pothwari/Pothohari and Hindko, which are dialects of Punjabi. Other varieties of Punjabi spoken in Britain include northern, eastern, southern, and western dialects. According to an Ethnologue report, the number of speakers of such languages (as a primary language) in the United Kingdom are shown below. Please note that some of these languages are not only spoken by British Pakistanis, but also by other groups such as British Indians and British Afghans, these are indicated by an asterix.

- Eastern Panjabi* (also spoken in India) - 471,000 speakers as a first language

- Urdu - 400,000

- Gujarati* (also spoken in India) - 140,000

- Kashmiri* (also spoken in India) - 115,000

- Western Punjabi - 102,500

- Southern Pashto* (also spoken in Afghanistan) - 87,000

- Northern Pashto* (also spoken in Afghanistan) - 75,000

- Saraiki - 30,000

- Mirpur Punjabi - 20,000

Culture

Pakistan's Independence Day is celebrated on 14 August of each year. The celebrations and events usually take place in large Pakistani populated areas of various cities in the United Kingdom, primarily on Green Street in Newham, London and the Curry mile in Manchester. The colourful celebrations last all day with various festivals. Pakistani Muslims from the community also mark the Islamic Festivals of Eid ul Adha and Eid ul Fitr.

Cuisine

See also: Anglo-Pakistani cuisine and Pakistani cuisine

Pakistani cuisine has a strong North Indian base which is then coupled with an exotic blend of Arabic, Persian and Turkish flavours. The Pakistani language of Urdu is also a mixture of Arabic, Persian and Turkish; which shows unity between the linguistic and culinary divisions of Pakistani culture. Kashmiri and Punjabi cuisine is well represented in Britain, reflecting the ethnic backgrounds of Pakistanis who live in Britain. The Balti dish has its roots in Birmingham, where the dish was created by a Kashmiri origin Pakistani immigrant in 1977. In 2009, Birmingham City Council attempted to trademark the Balti dish, to give the curry Protected Geographical Status alongside items such as luxury cheese and champagne. The area of Birmingham where the Balti dish was first served is known locally as the Balti Triangle or "Balti Belt". Chicken tikka masala has long been established amongst the nation's favourite dishes, there has been support for a campaign in Glasgow to give European Union Protected Designation of Origin status to chicken tikka masala.

In addition to this, many self employed British Pakistanis own takeaways and restaurants. Pakistanis are well represented in the British food industry, as "Indian restaurants" in the north of England are almost entirely Pakistani owned. Kashmiri and Punjabi origin curry sauces are sold in British supermarkerkets by British Pakistani entrepeners such as the Manchester born Nighat Awan. Awan's Asian food business, Shere Khan, has made her one of the richest women in Britain. Mumtaz is one of the most high profile Pakistani restaurant in the UK. Its flagship store is in Bradford, where famous diners have included the Prime Minister David Cameron and Queen Elizabeth II.

Sport

Cricket was first documented as being played in southern England. The expansion of the British Empire led to cricket being played overseas, Pakistan being a well known country for the sport. Sajid Mahmood, Adil Rashid and Ajmal Shahzad currently play cricket for England. There are several other British Pakistanis who play county cricket.

Cricket is a core part of Pakistani culture and is often played by British Pakistanis for leisure and recreation. Hockey and polo are commonly played in Pakistan but these sports are not as popular with British Pakistanis, lack of popularity for the latter sports are possibly due to the urban lifestyles which the majority of British Pakistanis lead.

Famous British Pakistani sports people outside of cricket include Adam Khan who is racing driver from Bridlington, Yorkshire. He represents Pakistan in the A1 Grand Prix series. Khan is currently the demonstration driver for the Renault F1 racing team. Ikram Butt was the first South Asian to play code of international rugby for England in 1995. He is founder of the British Asian Rugby Association and the British Pakistani rugby league team. Amir Khan is the most famous British Pakistani boxer. He is the current WBA World light welterweight champion and 2004 Olympics Silver Medalist.

Assimilating into British society

Kashmiris

Around half of the British Pakistanis living in Britain can trace their origins to Mirpur in Azad Kashmir. In contrast to Punjabis who arrived from rain-fed farms and urban areas of Jhelum, Gujrat and Gujranwala, Mirpuris were less educated and they had little or no experiences of urban living in Pakistan. Mirpur was the site of the Mangla Dam, which was built in the 1960s and flooded the surrounding farmland. Mirpur is a conservative district, even by Pakistani standards and rural life here has not changed much over the years. Families are not only a source of rigid hierarchies, but also the guiding influence behind everything from marriage to business. This has clashed with British values, in which people tend to be more independent and liberal. As a result, Kashmiri Pakistanis commonly live in secluded areas and avoid cross-cultural contact, thus the rise of ghettos in those communities. Mirpuris live in the most segregated areas of Britain, and their children attend the most segregated schools. The British government has dedicated itself to helping immigrants, providing some kind of shared identity which Pakistanis could learn to accept. One plan includes the busing of Pakistani background students to "white schools" in an attempt to bridge the divide between the British public and Pakistanis.

Many Kashmiris have named their businesses after the Pakistani area, one of the largest companies incorporating such a name is Kashmir Crown Bakeries which is a food making business based in Bradford. The company is a major local employer and is the largest Asian Food Manufacturer in Europe. The owner of Kashmir Crown Bakeries, Mohammed Saleem, claims that combining traditional Kashmiri Baking methods with vocational British training has given his baking business a multi-million pound turnover.

Punjabis

Punjabis make up the second largest sub-group of British Pakistanis, they are estimated to make up a third of the British Pakistani population. Around half of the Punjabis living in Britain are from Pakistan, with the other half being from India. As a result, two thirds of British Asians are of Punjabi descent, this has made Punjabi the second most commonly spoken language in the UK after English.

People who came from the Punjab area of Pakistan have integrated much more easily into British society because the Punjab forms a mostly prosperous part of Pakistan. Early Punjabi immigrants to Britain tended to be more highly educated than Kashmiris, they found it easier to assimilate because many already had basic knowledge of the English language. British Punjabis are commonly found in the south of the England and the major cities in the north (as opposed to peripheral mill towns). Research by Teesside University has found that British Punjabi communities of late, have become some of the most highly educated and economically successful ethnic minorities in the UK.

James Caan and Amir Khan are examples of famous Punjabi Pakistanis who work in the fields of business and sport respectively.

Contemporary issues

Allegations of extremism

The publication of Salman Rushdie's Satanic Verses in 1988 is said to have been a precursor for the September 11th attacks. The publication of The Satanic Verses coupled with violence in the Middle East radicalised men whose grandparents had come to the UK from Pakistan. Many British Pakistanis considered the book to have blasphemous references. It was first published in the UK and it led to protests which several British Pakistanis took part in, many of these protests were of a violent nature, where copies of Rushdie's book were burned, the protests often took part in Pakistani populated areas such as Bradford.

In February 2009, it was reported that the Central Intelligence Agency believed that a British-born Pakistani extremist entering the US under the Visa Waiver Program was the most likely source of a major terrorist attack on American soil. Gareth Price, head of the Asia Program at the Royal Institute of International Affairs in London stated that British Pakistanis are more likely to be radicalised as compared to other Muslim communities in Britain. In response to these issues the government has launched a "prevent strategy" which aims to stop radicalisation within British Pakistani communities. The initiative has given grants and financial support to community projects. £53m has been spent on the strategy between 2007–2010.

Discrimination

British Pakistanis were eight times more likely to be victims of a racist attack than white individuals in 1996. The chances of a Pakistani being racially attacked in a year is more than 4 per cent - the highest rate in the country, along with British Bangladeshis. Though, this has come down from 8 per cent a year in 1996. The sensitive term "Paki" is often used as a racist slur to describe Pakistanis and can also be directed towards non-Pakistani south Asians. There have been some attempts by the youngest generation of British Pakistanis to reclaim the word and use it in a non-offensive way to refer to themselves, though this remains controversial.

Health and social issues

On average, British Pakistanis, male and female, claim to both have had only one sexual partner. On average, British Pakistani males claim to have lost their virginity at the age of 20 and females at 22, thus giving an average of 21 years. 3.2 per cent of Pakistani males report that they have been diagnosed with an STI, compared to 3.6 per cent of Pakistani females. These statistics can be explained by the role of cultural norms, regarding issues such as multiple partners and the age of losing one's virginity, resulting in substantially older age of first intercourse, lower number of partners and low STI rates.

Endogamy and kinship

Cousin marriages are common in some parts of South Asia, they are typical in Southern India and in rural parts of Pakistan. The reasons why cousin marriages occur in South Asia are complex, though a major reason for it is to preserve any patrilineal tribal identity. The tribes to which British Pakistanis belong include Jats, Gujjars and Rajputs, all of whom are spread throughout India and Pakistan. As a result there are some common genealogical origins within these tribes. Some Kashmiri British Pakistanis view cousin marriages as a way of preserving this ancient tribal tradition and maintaining a sense of brotherhood. Contemporary scientific research though suggests that cousin marriages can result in birth defects, illness and infant mortality. A BBC report found that the children of British Pakistanis who marry a first cousin are thirteen times more likely to have genetic disorders. The report also found that one in ten children of cousin marriages either dies in infancy or develops a serious disability. Thus British Pakistanis, who account for some 3 per cent of all births in the UK, account for just under a third of all British children with genetic illnesses. A study published in 1988 in the Journal of Medical Genetics, which looked specifically at two hospitals in West Yorkshire, found that the rate of consanguineous marriage was 55 per cent and rising. However, representatives of constituencies where there are high Pakistani populations say that consanguineous marriages amongst British Pakistanis are now decreasing in number, partly because of public health initiatives. The rate of consanguineous marriages around the world is around 29 per cent.

Forced marriage

According to the British Home Office, as of 2000 more than half the cases of forced marriage investigated involve families of Pakistani origin, followed by Bangladeshis and Indians. The British Home Office estimates that 85 per cent of victims of forced marriages are women, aged 15–24, 90 per cent are Muslim and 90 per cent are of Pakistani or Bangladeshi heritage. 60 per cent of the cases involving forced marriages by Pakistani families are linked to the small Kashmiri towns of Bhimber and Kotli and the Kashmiri city of Mirpur.

Education

GCSEs

British Pakistani students achieve below national GCSE pass rates. However, the British Pakistani GCSE pass rate has steadily increased since 1999, bridging the gap towards the UK national average, year by year. In addition, the British Pakistani GCSE pass rate fails to distinguish between the differences in achievement around the country, since Pakistani pupils have greater regional fluctuations than others. This is a result of differences in material circumstances, social class and migration histories between the different communities of British Pakistanis.

Already in 2004, Pakistani pupils from London were achieving above the regional and UK national averages. 50.2 per cent of Pakistani boys and 63.3 per cent of Pakistani girls from London achieved five or more A*-C grades. Compared to the national averages of 46.8 per cent and 57 per cent, for boys and girls, respectively. By 2008, the figure for British Pakistani students passing 5 or more GCSE's increased to 58.2 per cent, showing an improvement of almost 10 per cent, between 2005 & 2008. In 2009 the attainment gap was reduced to 3.4 per cent.

| Year | Pakistani Pupils | All Pupils | Attainment Gap | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 26% | 37% | -11% | |

| 1993 | 24% | 42% | -18% | |

| 1995 | 23% | 44% | -21% | |

| 1997 | 29% | 46% | -17% | |

| 1999 | 30% | 49% | -19% | |

| 2001 | 40% | 51% | - 11% | |

| 2003 | 41.5% | 52% | - 10.5% | |

| 2005 | 48.4% | 54.9% | - 6.5% | |

| 2007 | 53% | 59.3% | - 6.3% | |

| 2008 | 58.2% (boys: 52.7%) (girls: 64%) |

63.5% | - 5.3% | |

| 2009 | 66.4% (boys: 61.2%) (girls: 72%) |

69.8% (boys: 65.8%) (girls: 73.9%) |

- 3.4% (boys: - 4.6%) (girls: - 1.9%) |

University-level

British Pakistani students are 1.7 per cent of the 18 year olds in the country, but they make up 2.4 per cent of the first year students at University. Regions of predominantly non-Kashmiri settlement, such as Greater London and the South East are sources of greater university applications. University applicants are over represented by 7.5 per cent from Greater London and by 4.6 per cent from the South East. In contrast, they are under represented by 4.9 per cent from West Midlands, by 4.4 per cent from the East of England and by 4.3 per cent from Yorkshire and Humber. Whilst from other regions, there is a slight over representation by between 0.2 per cent to 0.6 per cent. 33 per cent of British Pakistani boys choose to continue their studies to the university level. This rate is the third highest rate in the country after Chinese and Indian boys and is higher than the rate for White British boys (23 per cent), Black African boys (30 per cent), Bangladeshi boys (29 per cent), Black Caribbean boys (16 per cent) and those falling into the other black category (20 per cent). Science and Mathematics are the most popular subjects at A level and degree level with the youngest generation of British Pakistanis, as they begin to establish themselves within the field.

Urdu

Urdu language courses are available in the UK and the subject can be studied at GCSE and A Level. Several British universities are hoping to offer degrees in Urdu in the future, these degrees would be open to established Urdu speakers as well as beginners.

Economics

The demise of traditional manufacturing industries in northern Mill towns have limited entrepreneurial success of the British Pakistanis who live in these areas. While the lower class resources and inner-city living have hampered social mobility. The existence of a North-South divide leaves Pakistanis in the north of England economically depressed, although there is a small concentration of better educated Pakistanis living in the suburbs of Greater Manchester and West Yorkshire, as certain individuals have taken advantage of the opportunities that arise from living in a major city.

Location in Britain has had a great impact on the success of British Pakistanis. British Pakistanis based in large cities such as London and Manchester have found making the transition into the professional middle class easier than those based in the peripheral towns. This is due to the fact that cities like Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, Liverpool, Newcastle, Glasgow and Oxford have provided a more economically encouraging environment for Pakistani entrepreneurs. Other small towns in Lancashire and Yorkshire have provided far fewer economic opportunities. Most of the initial funds for entrepreneurial activities were historically collected by working in food processing and clothing factories. The funds were often given a boost by wives saving "pin money" and interest free loans which were exchanged between fellow migrants. British Pakistanis soon began dominating the ethnic & halal food businesses, Indian restaurants, Asian fabric shops and travel agencies by the 1980s. Some other Pakistanis secured ownership of clothes manufacturing and wholesaling businesses and took advantage of cheap family labour. The once multi-million pound company Joe Bloggs has such origins. Clothing imports from South East Asia began to affect the financial success of these mill owning Pakistanis in the 1990s. However, it did not manage to stop some Pakistani families in Manchester, Birmingham and Leicester from prospering financially in other ways such as by selling or renting out their own former factories.

In the housing rental market, Pakistani landlords first rented out rooms to incoming migrants (who were mostly Pakistani themselves). As these rentees settled in Britain and worked to a position that they could afford to buy their own homes, non-Asian university students became the main potential customers to these landlords. By the year 2000, several British Pakistanis had established low-cost rental properties throughout England. British Pakistanis are most likely to live in owner-occupied Victorian terraced houses of the inner city Though there is an increasing suburban movement amongst Pakistanis living in Britain, this suburban trend is most conspicuous among children of Pakistani immigrants. Pakistanis tend to place a strong emphasis on owning their own home, so as a result Pakistanis have one of the highest rates of home ownership in the UK at 73 per cent, which is slightly higher than the rate of home ownership among the White British population. Aneel Mussarat is an example of a property millionaire whose company, MCR Property Group, specialises in renting apartments to university students in Manchester and Liverpool. There were around 100 British Pakistani millionaires in 2001, these millionaires represent a variety of industries.

Many first generation British Pakistanis have invested in second homes or holiday homes in Pakistan. They have purchased houses next to their villages and sometimes even in more expensive cities, such as Islamabad and Lahore. Upon reaching retirement age, some migrant Pakistanis hand over their houses in Britain to their offspring and settle back into their second homes in Pakistan. Relocating to Pakistan for retirement allows the value of these peoples British state pensions to multiply significantly. Investing in Pakistan has in many cases limited success due to lack of financial returns and less favourable exchange rates. In comparison, other migrant groups such as the Indian refugees from East Africa have benefited from investing only in Britain.

Famous business people include James Caan (of Dragon's Den - a popular Business reality television programme for the BBC), Lord Nazir Ahmed (Baron Ahmed, member of the House of Lords), Anwar Pervez (CEO of Bestway and the international banking giant United Bank Limited, who has employed thousands of people in the UK), Shahid Luqman (from Manchester, founder of Pearl Holdings Group who specialise in finance), Abdul Bhati (a wholesaler of products whose company turns over hundreds of millions of pounds a year), Afzal Kushi (of Glasgow, Scotland) who is the managing director of Jacobs & Turner, who's also founded a global sportswear firm). and Sir Gulam Noon (who is the owner of a West London curry & food business).

Poverty

Statistics from the 2001 census show that Pakistani communities in England, particularly in the North and the Midlands, are severely affected by poverty, unemployment and social exclusion, and that they are much less likely than the majority of the population to be employed in managerial and professional occupations. Statistics by the DfES show that almost 40 per cent of Pakistani students in secondary schools are eligible for free school meals, this compares with a national average of 15 per cent. A study by Joseph Rowntree Foundation in 2007 found that Pakistani Britons have the second highest relative poverty rates in Britain, second only to Bangladeshis. Their study found the following:

| Ethnic group | Percentage in poverty |

|---|---|

| Bangladeshi | 65% |

| Pakistani | 55% |

| Black African | 45% |

| Black Caribbean | 30% |

| Indian | 25% |

| White Other | 25% |

| White British | 20% |

Employment

As of 2001, around 3,500 British Pakistanis were in the highest ranking business and professional occupations, compared to 1,000 Bangladeshis and 10,000 Indians. Keeping in mind the lower class resources of Kashmiris, the rates of entry of non-Kashmiri Pakistanis, into managerial or professional occupations, turns out to be similar to that of British Indians.

Research by the Office for National Statistics shows that British Pakistanis are far more likely to be self-employed than any other ethnic group. Pakistani men are most likely to work in the transport and logistics industry, most British Pakistanis in this sector are employed as cab drivers and taxi drivers. In 2004, 69 per cent of working-age British Pakistani women were economically inactive, second highest only to British Bangladeshi women, and of those who are economically active, 20 per cent were unemployed. Amongst employed Pakistani women, many work as packers, bottlers, canners or fillers, or as sewing machinists.

Social class

The majority of British Pakistanis are considered to be working class. According to the 2001 Census, 13.8 per cent of Pakistanis living in Great Britain were in managerial or professional occupations, 14 per cent were in intermediate occupations and 23.3 were in routine or manual occupations. The remainder were long-term unemployed, students, or not classified due to a lack of data. Whilst British Pakistanis living in the Midlands and the North are particularly more likely to be unemployed or suffer from social exclusion, some Pakistani communities in London and the south-east are said to be "fairly prosperous". It was estimated that in 2001 around 45 per cent of British Pakistanis living in both inner and outer London were middle class.

Media

Cinema

Famous films that depict the life of British Pakistanis include My Beautiful Laundrette, which received a BAFTA award nomination, and the popular East is East. The Infidel looked at a British Pakistani family living in East London. The Infidel depicted religious issues and the identity crisis facing a young member of the family. The film Four Lions also looked at issues of religion and extremism. It followed British Pakistanis living in Sheffield in the North of England. Indian Bollywood films are also shown in some British cinemas and are popular with many second generation British Pakistanis/British Asians. The sequel to East is East, called West is West was released in the UK on 25th February 2011.

Television

In 2005, the BBC showed an evening of programmes under the title Pakistani, Actually. The programmes offered an insight into the lives of Pakistanis living in Britain and some of the issues the community face. The executive producer of the series said:

These documentaries provide just a snapshot of contemporary life among British Pakistanis - a community who are often misunderstood, neglected or stereotyped.

The Pakistani channels of ARY Digital and GEO TV are available to watch on subscription. These channels are based in Pakistan and they cater to the Pakistani diaspora as well as anyone of South Asian origin. The channels feature news, sports and entertainment with some channels broadcast in Urdu/Hindi. In relation to British broadcasting channels though, Mishal Husain is a newsreader and presenter for the BBC of Pakistani descent. Saira Khan hosts the BBC children's programme Beat the Boss. Anita Anand is a Hindu Pakistani and another BBC presenter and journalist. Martin Bashir is a Christian Pakistani and previously worked for ITV before later moving to work for the American Broadcasting Company.

Radio

The BBC Asian Network is a radio station available across the entire United Kingdom and is aimed at Britons of South Asian origin under 35 years of age. Apart from this popular station, there are many other national radio stations for or run by the British Pakistani community - including Sunrise and Kismat Radios of London. Regional British Pakistani stations include Asian Sound of Manchester, Radio XL of Birmingham and Sunrise Radio Yorkshire which based in Bradford. These radio stations generally run programmes in a variety of South Asian languages.

A large proportion of newspaper vendors and newsagents in Britain are run by Indian and Pakistani families. The fact that Pakistanis have traditionally owned a newsagent or corner shop is well known in Britain and has led to the term “Paki shop” being used. This foothold in the retail sector has on one occation been influential to those of a Muslim faith, as the tabloid newspaper The Daily Star once planned to publish a spoof page that mocked Sharia law. The special feature, which was to include censored "Burka Babes" and "a free beard for every bomber", was eventually pulled from publication partially because staff at the Daily Star discovered that:

Many of the newsagents who sell the paper are of Pakistani origin and would have been offended

The Pakistani newspaper the Daily Jang is the largest Urdu-language newspaper in the world and is sold at several Pakistani newsagents and grocery stores across the UK. Urdu newspapers, books and other periodical publications are available in libraries which have a dedicated Asian languages service. Examples of British-based newspapers written in English include the Asian News (published by Trinity Mirror) and the Eastern Eye. These are free weekly newspapers aimed at all British Asians. British Pakistanis involved in print media include Sarfraz Manzoor, who is a regular columist for The Guardian, one of the largest and most popular newspaper groups in the UK. While Anila Baig is a feature writer at The Sun, the biggest-selling newspaper in the UK. Mehdi Hasan is a senior politics editor at the New Statesman, which is a weekly political magazine.

Politics

British Pakistanis make up a sizable proportion of British voters and votes from the community are known to make a difference in an election (both local and national). As of 2007, 257 British Pakistanis were serving as elected councillors or mayors in Britain. There are also four British Pakistani MPs in the House of Commons including two ministers. Furthermore, Pakistanis are much more active in the voting process, with 67 per cent voting in the last general elections of 2005, compared to the figure of just over 60 per cent for the whole country.

The Conservative party and the Labour party have traditionally made up the two largest political parties in Britain. There are increasing numbers of British Pakistanis getting involved with these two political parties and with other smaller parties:

Labour party

The Labour party has traditionally been the natural choice for many British Pakistanis, a 2005 poll carried out by ICM showed that 40 per cent of Pakistanis in Britain intended to vote for Labour compared to 5 per cent who wanted to vote for the Conservative party and 21 per cent intending to vote for the Liberal Democrats. The Labour party are also said to be more dependent on votes from British Pakistanis than the Conservative party. But the level of support for Labour has fallen in recent times because of party's decision to take part in the Iraq War. High profile Pakistani origin politicians within the Labour Party include Shahid Malik and Lord Nazir Ahmed. Sadiq Khan became the first Muslim cabinet minister in June 2009 after being invited to the post by the former Prime Minister Gordon Brown.

Conservative party

The Conservative Party have become increasingly popular with many affluent British Pakistanis. David Cameron opened a new gym aimed at British Pakistanis in Bolton after being invited by Amir Khan in 2009. David Cameron of the Conservative party also appointed Lord Ahmed, a Kashmiri born politician, a life peerage which made Ahmed the first Pakistani peer in the UK. Multi-millionaire Sir Anwar Pervez, who claims to have been born Conservative, has donated large sums to the party. Sir Anwar's donations have entitled him to become a member of the influential Conservative Leader's Group. Shortly after becoming the Conservative party leader, David Cameron spent two days living with a British Pakistani family in Birmingham. Cameron said that the experience made him learn more about the challenges of cohesion and integration.

Sajjad Karim is a Member of the European Parliament. He represents North West England through the Conservative Party. In 2005 Karim became the founding Chairman of the European Parliament Friends of Pakistan Group. He is also a member of the Friends of India and Friends of Bangladesh groups. Rehman Chishti became the new Conservative Party MP for Gillingham and Rainham. He secured more votes than the transport minister Paul Clark, polling 21,264 votes to Clark's 12,944. Sayeeda Warsi was promoted to Chairman of the Conservative Party by the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom shortly after the UK General Election, 2010. Warsi was the shadow minister for community cohesion when the Conservatives were in opposition. She is the first Muslim woman to serve in a British cabinet. Both of Warsi's grandfathers served with the British Army in the Second World War.

Others

In the 2003 Scottish Parliament elections, Scottish Pakistani voters were more likely to vote for the Scottish National Party (SNP) than the average Scottish voter. The SNP is a centre-left civil nationalist party that campaigns for the independence of Scotland from the United Kingdom. SNP candidate Bashir Ahmad was elected to the Scottish Parliament to represent Glasgow at the 2007 election, becoming was the first MSP to be elected from a Scottish Asian or background.

Salma Yaqoob is leader of the left wing Respect party. The small party has seen success in areas such as Sparkbrook in Birmingham and Newham in London, where there are large Pakistani populations. While Qassim Afzal is the most senior Liberal Democrat politician of Pakistani origin. He has previously accompanied the Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in meetings with Pakistan’s President, Asif Ali Zardari.

Notable people

Further information: List of British people of Pakistani descentSee also

Related groups

Related Pakistanis

Other

References

- "Population size: 7.9% from a non-White ethnic group". Office for National Statistics. 8 January 2004. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ Nadia Mushtaq Abbasi. "The Pakistani Diaspora in Europe and Its Impact on Democracy Building in Pakistan" (PDF). International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ Werbner, Pnina (2005). "Pakistani migration and diaspora religious politics in a global age". In Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (eds.). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures around the World. New York: Springer. pp. 475–484. ISBN 0306483211.

- ^ Satter, Raphael G. (2008-05-13). "Pakistan rejoins Commonwealth - World Politics, World". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Butler, Patrick (18 June 2008). "How migrants helped make the NHS". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ "Britain's Pakistani community". The Daily Telegraph. 28 Nov 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ "Ethnic groups by religion". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- "The First Asians in Britain". Fathom. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- Fisher, Michael Herbert (2006). Counterflows to Colonialism: Indian Traveller and Settler in Britain 1600-1857. Orient Blackswan. pp. 111–9, 129–30, 140, 154–6, 160–8, 172. ISBN 8178241544.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - D. N. Panigrahi, India's Partition: The Story Of Imperialism In Retreat, 2004; Routledge, p. 16

- Marco Giannangeli. "Links to Britain forged by war and Partition". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ Sophie Hares (Fri Jul 3, 2009). ""Untold" story of WW2 stirs Muslim youth pride". Reuters. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Robin Richardson and Angela Wood. "The Achievement of British Pakistani Learners" (PDF). Trentham Books.

- "Muslims In Britain: Past And Present". Islamfortoday.com. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Kinship and continuity: Pakistani families in Britain. Routledge. 2000. ISBN 9789058230768. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Museum of London (2004-09-21). "subject home". Museum of London. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Bizeck J.Phiri. "Asians: East Africa". Glam Media. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- Minority Rights Group. "East African Asians". Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ "National Statistics Online - Employment Patterns". Office for National Statistics. 2006-02-21. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ Dobbs, Joy; Green, Hazel; Zealey, Linda, eds. (2006). Focus on Ethnicity and Religion 2006 (PDF). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan/Office for National Statistics. pp. 30, 41. ISBN 1403993289.

- "Population size: 7.9% from a non-White ethnic group". Office for National Statistics. 8 January 2004. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- "Estimated population resident in the United Kingdom, by foreign country of birth (Table 1.3)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ Department for Communities and Local Government. "The Pakistani Muslim Community in England" (PDF). Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- "FEATURE - Support for Taliban dives among British Pashtuns | South Asia | Reuters". Reuters. 2009-06-10. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Abbas, Tahir, ed. (2005). "Britain's Muslim population: An overview". Muslim Britain: Communities under Pressure. London: Zed Books. pp. 18–30. ISBN 1842774492.

- "Distribution of ethnic groups across regions, April 2001/Distribution of ethnic groups within regions, April 2001". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- Piggott, Gareth (January 2005). "2001 Census Profiles: Pakistanis in London" (PDF). Greater London Authority. p. 5. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Pakistani london". Renaissance London. Retrieved 2010-12-23.

- ^ Instead. "The raise project". Yorkshire Forward. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- The Guardian. "London by ethnicity". Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- Zameer Choudrey. "Bestway Group's turnover exceeds £2BN". WholesaleManager. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Moore-Gilbert, Bart (2001). Hanif Kureishi. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0719055350.

- Neighbourhood statistics. "Resident Population Estimates by Ethnic Group". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Dr David Parker and Dr Christian Karner. "Remembering the Alum Rock Road" (PDF). University of Nottingham. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "A Brief History of the Bangladesh Community". Birmingham City Council. 27 February 2008. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved 23-12-2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "The Afghan community in England". Department for communities and local governments. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "Persian/Farsi". BBC voices. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Banuazizi, Ali and Weiner, Myron (eds.). The State, Religion, and Ethnic Politics: Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan (Contemporary Issues in the Middle East), Syracuse University Press (August, 1988). ISBN 0-8156-2448-4.

- Birmingham City Council. "Diverse Birmingham". Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Shackle, Samira (20 August 2010). "The mosques aren't working in Bradistan". New Statesman. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- Tim Smith. "Immigration and emigration". BBC Legacies. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- Shiv Malik. "A community in denial". New Statesman. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "Bradford counts cost of riot". BBC News Online. BBC. 8 July 2001. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "Last Bradford rioter is sentenced". BBC News. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "Resident Population Estimates by Ethnic Group". Office for National Statistics. 2001. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Scotland against racism. "Ethnicity Data". One Scotland. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "Background of Glasgow". The Pakistani film, media and arts festival. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "What do you know about Pollokshields?". Herald & Times Group. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "Associated Press Of Pakistan ( Pakistan's Premier NEWS Agency ) - PIA inaugural flight from Glasgow to Faisalabad". App.com.pk. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ Kelbie, Paul (2003-10-30). "Pakistanis living in Scotland feel more at home north of the border than the 400,000 English who live there - This Britain, UK". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Lynn Jolly. "Peter is Scotland's first Pakistani minister". Paisley Daily Express. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ John Moss. "Manchester Population". Manchester 2002. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Asian News. "Violent racists menace affluent suburb". Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "home". cmatrust.org. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "Linguistic and Ethnic Groups". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- William Stewart. "UK madrassas coach borderline pupils". TES Connect. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "Case study". Department for Children, Schools and Families. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ Ager, Denis (2003). Ideology and Image: Britain and Language. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. p. 191. ISBN 1853596590.

- "Punjabi Dialects and geographic distribution". Punjabi world. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "Ethnologue report for United Kingdom". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "British Pakistani Muslims in UK celebrate Eid ul Fitr with traditional zeal". Pakistan Daily. Thursday, October 2, 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Pakistani society". RolaGola. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- BBC Languages. "A Brief History of Urdu". BBC. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- BBC Legacies. "Birth of Birmingham's balti". BBC. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Nick Britten. "Birmingham bids to prevent curry houses elsewhere using word Balti". Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Neil Connor. "Balti belt a wonder to behold". Trinity Mirror Midlands. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- "Welcome to the Balti Triangle". Birmingham City Council. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- "Icons of England". Icons of England. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "UK Parliament Early Day Motions 2008-2009". The United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - The Guardian group. "Who are the British Asians?". The new statesman. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- Chris Barry. "From printing T-shirts to £30m food fortune". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Mumtaz Group. Mumtaz http://www.mumtaz.co.uk/. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

See website slideshow

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - H S Altham, A History of Cricket, Volume 1 (to 1914), George Allen & Unwin, 1962

- BBC World Service. "The birth and the journey through centuries". BBC. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- John Westerby (January 19, 2010). "Ajmal Shahzad fast-tracked into England squad". Times Newspapers Ltd. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Stephen Brenkley (Tuesday, 27 July 2010). "Pakistan has so much talent but we don't channel it properly". The Independent. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - LJ Hutchins. "F1: Adam Khan gets a break with Renault". Brits on Pole. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Wednesday 28 October 2009. "Trying times". Chris Arnot. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - John Moss. "Sports & Olympic Champions". Manchester UK. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- The limits to integration - BBC News, 30 November 2006

- Samira Shackle (20 August 2010). "The mosques aren't working in Bradistan". New Statesman. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Anthony Browne. "We can't run away from it: white flight is here too". The Times. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "The largest Asian Food Manufacturer in Europe". Kashmir Crown Bakeries. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "The History". Kashmir Crown Bakeries. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ Roger Ballard and Marcus Banks (1994). Desh Pardesh: the South Asian presence in Britain. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 18, 20, 21.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - "Punjabi Community". The United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved 2 November 2010

- National Geographic. "Pakistan". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Dr Steve Taylor. "Punjabi Communities in the North East". Teesside University. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Pierre Tristam. "An Appraisal of Salman Rushdie's "Satanic Verses"". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Brian Viner (9th Feb 2010). "Last Night's Television - Generation Jihad, BBC2; Getting Our Way, BBC4". The Independent. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Appignanesi, Lisa; Armitstead, Claire; Dugdale, John (6 December 2008). "The week in books". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- Tim Shipman (07 Feb 2009). "CIA warns Barack Obama..." The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Why Britain Increasingly Worries About Pakistani Terrorism". U.S. News & World Report. 2008-12-24. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- "The Prevent Strategy: A guide for local partners". Communities and Local Government. 3 June 2008. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- Dominic Casciani (Tuesday, 30 March 2010). "Prevent extremism strategy 'stigmatising', warn MPs". BBC News. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Ian Burrell. "Most race attack victims `are white'". The Independent. Retrieved 02/11/2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "Pakistanis are eight times more likely to be victim of a racist attack than whites - Home News, UK". The Independent. London. 2003-02-04. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Rajni Bhatia (Monday, 11 June 2007). "After the N-word, the P-word". BBC News. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Fleming, Nic (2005-04-01). "Love league tables show link to sexual disease". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "Marriage". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- "Birth defects warning sparks row". BBC News. 10 February 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- DeVotta, Neil (2003). Understanding Contemporary India. London: Lynne Rienner. ISBN 1555879586.

- Monika Böck and Aparna Rao (2000), , Berghahn Books, ISBN 1571819126, retrieved 2010-01-05,

... Kalesh kinship is indeed orchestrated through a rigorous system of patrilineal descent defined by lineage endogamy

{{citation}}: Check|url=value (help) - Zafar Khan. "Diasporic Communities and Identity Formation". University of Luton. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Rowlatt, J, (2005) "The risks of cousin marriage", BBC Newsnight. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- The frequency of consanguineous marriage among British Pakistanis, Journal of Medical Genetics 1988;25:186-190

- Asian News. "Calls for reviews of cousin marriages". Asian News. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- "Pakistan Faces Genetic Disasters - OhmyNews International". English.ohmynews.com. 2006-10-06. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Groups try to break bonds of forced marriage, USA Today, 2006-04-19

- Woman saved from forced marriage in Pakistan by new UK law, The Daily Telegraph, 2009-02-11

- "Cry freedom - Features - TES Connect". Tes.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ "Uncorrected Evidence tt16". Publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ "Youth Cohort Study & Longitudinal Study of Young People." (PDF). Department for Children, Schools and Families. 26 June 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- "EDUCATION | Pass rate rising for black pupils". BBC News. 2001-01-23. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/4294663.stm - For 2003, I took away the 3.7% increase from 2004's figure of 45.2%

- Alexandra Frean (November 28, 2007). "Black boys closing the grades gap". The Times. Retrieved 2 November 2010.]

- ^ ""Race", Ethnicity and Educational Achievement". Earlham Sociology. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Paul Bolton. "Trends in GCSE attainment gaps" (PDF). UK Parliament. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Laura Clark (2008-06-19). "As Black and Asian teenagers flock to university, WHITE working-class boys are shunning higher education | Mail Online". The Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "White students 'avoid maths and science' - Education News, Education - The Independent". The Independent. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "Urdu degree 'first' for city universities". The Asian News. 2010-04-06. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ^ Encyclopedia of diasporas: immigrant and refugee cultures around... Springer. 2005.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Pnina Werbner. (PDF). Keele University. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - "Showing 'crap town' Luton in new light". BBC News. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Ceri Peach. "A question of collar". Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Phillips, D., Davis, C. and Ratcliffe, P. (2007), British Asian narratives of urban space, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 32: 217–234. ISSN 0020-2754

- "'Myths' threaten racial harmony, say population experts (The University of Manchester)". Manchester.ac.uk. 2009-01-22. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "Policy briefing Home ownership" (PDF). Shelter. April 2006. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- "UK Pakistani Business Directory". Pakistani Business Directory. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Jerome Taylor. "Mystery of the missing father of kidnapped boy". The Independent. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "Pakistan's Super Rich People". Buzz Vines.com. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- "Muslims contribute 31b pounds to British economy". Pakistan Daily Times. Monday, February 12, 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Guy Palmer and Peter Kenway (29 April 2007). "Poverty rates among ethnic groups in Great Britain". JRF. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "Labour market: Non-White unemployment highest". Office for National Statistics. 21 February 2006. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- Andrew Gilligan (14 January 2010). "John Denham's right: It's class, not race, that determines Britain's have-nots". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- London's Turning: The Making of Thames Gateway. London. pp. 137, 138. ISBN 0754670635.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Omid Djalili becomes an Infidel". BBC. 2009-06-23. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- Sarfraz Manzoor (Thursday 29 May 2008). "Brits in Bollywood". Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "West Is West: world exclusive clip". Guardian. 2010-10-19. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ "Beds Herts and Bucks - Read This - Luton, actually". BBC. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "Luton Actually BBC2 Pakistani Actually". Video.google.com. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "Mishal Husain, a pretty asian face of BBC". The Asians. 2010-01-29. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Wells, Matt (2003-01-22). "Talk to me". The Guardian. London.

- BBC. "About the BBC". Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Sunrise Radio Yorkshire. "About Sunrise Radio". Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "Corner shop culture". BBC News. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Nina Lakhani (Sunday, 11 October 2009). "'Paki' wasn't funny 40 years ago. Why is it now, Bruce?". The Independent. Retrieved 12 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - James Silver (Sunday, 22 October 2006). "Dawn's 'Star' turn: a spoof too far". The Independent. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Ian Burrell (Thursday, 19 October 2006). "Newsroom revolt forces 'Star' to drop its 'Daily Fatwa' spoof". The Independent. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Daily Jang". Lycos.com. 2004-09-02. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "Asian Library Services". Manchester City Council. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Trinity Mirror. "http://menmedia.co.uk/asiannews/contact_us/s/1013220_contact_us".

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|title=|url=(help) - "Eastern Eye". Asian Media & Marketing Group. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- The Guardian. "Sarfraz Manzoor Profile". Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- The Sun, Audit Bureau of Circulations

- Race and politics: ethnic minorities and the British political system. Routledge. 1986. ISBN 9780422798402.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Perlez, Jane (2007-08-03). "Pakistani official tackles prejudice in Britain". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Alan Travis, home affairs editor (2008-04-08). "Officials think UK's Muslim population has risen to 2m | World news". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Pasternicki, Adam (2010-03-22). "How Conservatives' software targets Asian voters". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Tom Templeton. "The ethnic minority vote". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- David Leigh. "Cameron criticised radicalised Muslims: Wikileaks". The Hindu. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "War costs Labour the Muslim vote". The Muslim News. 2003-05-30. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "Tooting MP Sadiq Khan named first Muslim cabinet minister in Gordon Brown's reshuffle (From Wandsworth Guardian)". The Wandsworth Guardian. 2009-06-06. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "UK | UK Politics | In search of the Muslim vote". BBC News. 2008-04-18. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "David Cameron opens Amir Khan's gym in Bolton". YouTube. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Sathnam Sanghera (21 July 2007). "Slim margins mean fat profits for the man who supplies Britain's corner shops". The Times. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- "Frontrunners in fortune | UK news". The Guardian. London. 2002-03-06. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "The top political donors" (PDF). The Times. London. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- "Conservative Party donor clubs". The Conservative Party. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- David Cameron (Thursday, April 15, 2010). VB "What I learnt from my stay with a Muslim family". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - David Cameron (Sunday 13 May 2007). "What I learnt from my stay with a Muslim family". The Observer. London. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "The Conservative Party | People | Members of the European Parliament | Mr Sajjad Karim MEP". The Conservative Party. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- Steve Farrell (7 May 2010). "Bike-supporting Opik is election casualty". Bauer Publishing. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Janice Turner (October 17, 2009). "No garlic and silver bullets are needed for Nick Griffin". The Times. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- "First Asian MSP goes to Holyrood". BBC News. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "Pakistan President Asif Zardari meets Liberal Democrat Leader Nick Clegg". Liberal Democrats. 27th Aug 2009. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Further reading

|

| Africa | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia |

| ||||||||||

| Europe | |||||||||||

| Americas | |||||||||||

| Oceania | |||||||||||

| See also |

| ||||||||||

| Asian diasporas in the United Kingdom | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Asia | |||||

| East Asia | |||||

| South Asia | |||||

| Southeast Asia | |||||

| West Asia | |||||

| Ethnic group classifications in the 2021 UK Census | |

|---|---|

| White |

|

| Mixed |

|

| Asian or Asian British |

|

| Black or Black British |

|

| Other ethnic group | |

Categories: