This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Beetstra (talk | contribs) at 12:13, 6 December 2011 (Reverted edits by 203.116.251.237 (talk) to last version by The Pikachu Who Dared). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:13, 6 December 2011 by Beetstra (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by 203.116.251.237 (talk) to last version by The Pikachu Who Dared)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

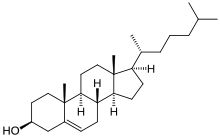

| IUPAC name (3β)-cholest-5-en-3-ol | |

| Other names (10R,13R)-10,13-dimethyl-17-(6-methylheptan-2-yl)-2,3,4,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-dodecahydro-1H-cyclopentaphenanthren-3-ol | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.321 |

| KEGG | |

| PubChem CID | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C27H46O |

| Molar mass | 386.65 g/mol |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Density | 1.052 g/cm |

| Melting point | 148–150 °C |

| Boiling point | 360 °C (decomposes) |

| Solubility in water | 0.095 mg/L (30 °C) |

| Solubility | soluble in acetone, benzene, chloroform, ethanol, ether, hexane, isopropyl myristate, methanol |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C , 100 kPa).

| |

Cholesterol is a waxy steroid of fat that is produced in the liver or intestines. It is used to produce hormones and cell membranes and is transported in the blood plasma of all mammals. It is an essential structural component of mammalian cell membranes and is required to establish proper membrane permeability and fluidity. In addition, cholesterol is an important component for the manufacture of bile acids, steroid hormones, and vitamin D. Cholesterol is the principal sterol synthesized by animals; however, small quantities can be synthesized in other eukaryotes such as plants and fungi. It is almost completely absent among prokaryotes including bacteria. Although cholesterol is important and necessary for mammals, high levels of cholesterol in the blood have been linked to damage to arteries and are potentially linked to diseases such as those associated with the cardiovascular system (heart disease).

The name cholesterol originates from the Greek chole- (bile) and stereos (solid), and the chemical suffix -ol for an alcohol. François Poulletier de la Salle first identified cholesterol in solid form in gallstones, in 1769. However, it was only in 1815 that chemist Eugène Chevreul named the compound "cholesterine".

Physiology

Since cholesterol is essential for all animal life, it is primarily synthesized from simpler substances within the body. However, high levels in blood circulation, depending on how it is transported within lipoproteins, are strongly associated with progression of atherosclerosis. For a person of about 68 kg (150 pounds), typical total body cholesterol synthesis is about 1 g (1,000 mg) per day, and total body content is about 35 g. Typical daily additional dietary intake in the United States is 200–300 mg. The body compensates for cholesterol intake by reducing the amount synthesized.

Cholesterol is recycled. It is excreted by the liver via the bile into the digestive tract. Typically about 50% of the excreted cholesterol is reabsorbed by the small bowel back into the bloodstream. Phytosterols can compete with cholesterol reabsorption in the intestinal tract, thus reducing cholesterol reabsorption.

Function

Cholesterol is required to build and maintain membranes; it modulates membrane fluidity over the range of physiological temperatures. The hydroxyl group on cholesterol interacts with the polar head groups of the membrane phospholipids and sphingolipids, while the bulky steroid and the hydrocarbon chain are embedded in the membrane, alongside the nonpolar fatty acid chain of the other lipids. Through the interaction with the phospholipid fatty acid chains, cholesterol increases membrane packing, which reduces membrane fluidity. In this structural role, cholesterol reduces the permeability of the plasma membrane to neutral solutes, protons, (positive hydrogen ions) and sodium ions.

Within the cell membrane, cholesterol also functions in intracellular transport, cell signaling and nerve conduction. Cholesterol is essential for the structure and function of invaginated caveolae and clathrin-coated pits, including caveola-dependent and clathrin-dependent endocytosis. The role of cholesterol in such endocytosis can be investigated by using methyl beta cyclodextrin (MβCD) to remove cholesterol from the plasma membrane. Recently, cholesterol has also been implicated in cell signaling processes, assisting in the formation of lipid rafts in the plasma membrane. Lipid raft formation brings receptor proteins in close proximity with high concentrations of second messenger molecules. In many neurons, a myelin sheath, rich in cholesterol, since it is derived from compacted layers of Schwann cell membrane, provides insulation for more efficient conduction of impulses.

Within cells, cholesterol is the precursor molecule in several biochemical pathways. In the liver, cholesterol is converted to bile, which is then stored in the gallbladder. Bile contains bile salts, which solubilize fats in the digestive tract and aid in the intestinal absorption of fat molecules as well as the fat-soluble vitamins, A, D, E, and K. Cholesterol is an important precursor molecule for the synthesis of vitamin D and the steroid hormones, including the adrenal gland hormones cortisol and aldosterone, as well as the sex hormones progesterone, estrogens, and testosterone, and their derivatives.

Some research indicates cholesterol may act as an antioxidant.

Dietary sources

Animal fats are complex mixtures of triglycerides, with lesser amounts of phospholipids and cholesterol. As a consequence, all foods containing animal fat contain cholesterol to varying extents. Major dietary sources of cholesterol include cheese, egg yolks, beef, pork, poultry, fish, and shrimp.

Human breast milk also contains significant quantities of cholesterol.

From a dietary perspective, cholesterol is not found in significant amounts in plant sources. In addition, plant products such as flax seeds and peanuts contain cholesterol-like compounds called phytosterols, which are believed to compete with cholesterol for absorption in the intestines. Phytosterols can be supplemented through the use of phytosterol containing functional foods or nutraceuticals which are widely recognized as having a proven LDL cholesterol lowering efficacy. Current supplemental guidelines recommend doses of phytosterols in the 1.6-3.0 grams per day range (Health Canada, EFSA, ATP III,FDA) with a recent meta-analysis demonstrating an 8.8% reduction in LDL-cholesterol at a mean dose of 2.15 gram per day. However, the benefits of a diet supplemented with phytosterol has been questioned.

Total fat intake, especially saturated fat and trans fat, plays a larger role in blood cholesterol than intake of cholesterol itself. Saturated fat is present in full fat dairy products, animal fats, several types of oil and chocolate. Trans fats are typically derived from the partial hydrogenation of unsaturated fats, and do not occur in significant amounts in nature. Trans fat is most often encountered in margarine and hydrogenated vegetable fat, and consequently in many fast foods, snack foods, and fried or baked goods.

A change in diet in addition to other lifestyle modifications may help reduce blood cholesterol. Avoiding animal products may decrease the cholesterol levels in the body not only by reducing the quantity of cholesterol consumed but also by reducing the quantity of cholesterol synthesized. Those wishing to reduce their cholesterol through a change in diet should aim to consume less than 7% of their daily energy needs {metric units Joules (J) or (kJ), pre-SI calories (Cal) or (kcal)} from animal fat and fewer than 200 mg of cholesterol per day.

It is debatable that a diet, changed to reduce dietary fat and cholesterol, can lower blood cholesterol levels, (and thus reduce the likelihood of development of, among others, coronary artery disease leading to coronary heart disease), because any reduction to dietary cholesterol intake could be counteracted by the organs compensating to try to keep blood cholesterol levels constant. Also pointed out is the experimental discovery that in the diet, ingested animal protein can raise blood cholesterol more than the ingested saturated fat or any cholesterol.

Biosynthesis

All animal cells manufacture cholesterol with relative production rates varying by cell type and organ function. About 20–25% of total daily cholesterol production occurs in the liver; other sites of higher synthesis rates include the intestines, adrenal glands, and reproductive organs. Synthesis within the body starts with one molecule of acetyl CoA and one molecule of acetoacetyl-CoA, which are hydrated to form 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA (HMG-CoA). This molecule is then reduced to mevalonate by the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase. This step is the regulated, rate-limiting and irreversible step in cholesterol synthesis and is the site of action for the statin drugs (HMG-CoA reductase competitive inhibitors).

Mevalonate is then converted to 3-isopentenyl pyrophosphate in three reactions that require ATP. Mevalonate is decarboxylated to isopentenyl pyrophosphate, which is a key metabolite for various biological reactions. Three molecules of isopentenyl pyrophosphate condense to form farnesyl pyrophosphate through the action of geranyl transferase. Two molecules of farnesyl pyrophosphate then condense to form squalene by the action of squalene synthase in the endoplasmic reticulum. Oxidosqualene cyclase then cyclizes squalene to form lanosterol. Finally, lanosterol is then converted to cholesterol.

Konrad Bloch and Feodor Lynen shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1964 for their discoveries concerning the mechanism and regulation of cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism.

Regulation of cholesterol synthesis

Biosynthesis of cholesterol is directly regulated by the cholesterol levels present, though the homeostatic mechanisms involved are only partly understood. A higher intake from food leads to a net decrease in endogenous production, whereas lower intake from food has the opposite effect. The main regulatory mechanism is the sensing of intracellular cholesterol in the endoplasmic reticulum by the protein SREBP (sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 and 2). In the presence of cholesterol, SREBP is bound to two other proteins: SCAP (SREBP-cleavage-activating protein) and Insig1. When cholesterol levels fall, Insig-1 dissociates from the SREBP-SCAP complex, allowing the complex to migrate to the Golgi apparatus, where SREBP is cleaved by S1P and S2P (site-1 and -2 protease), two enzymes that are activated by SCAP when cholesterol levels are low. The cleaved SREBP then migrates to the nucleus and acts as a transcription factor to bind to the sterol regulatory element (SRE), which stimulates the transcription of many genes. Among these are the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor and HMG-CoA reductase. The former scavenges circulating LDL from the bloodstream, whereas HMG-CoA reductase leads to an increase of endogenous production of cholesterol. A large part of this signaling pathway was clarified by Dr. Michael S. Brown and Dr. Joseph L. Goldstein in the 1970s. In 1985, they received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work. Their subsequent work shows how the SREBP pathway regulates expression of many genes that control lipid formation and metabolism and body fuel allocation.

Cholesterol synthesis can be turned off when cholesterol levels are high, as well. HMG CoA reductase contains both a cytosolic domain (responsible for its catalytic function) and a membrane domain. The membrane domain functions to sense signals for its degradation. Increasing concentrations of cholesterol (and other sterols) cause a change in this domain's oligomerization state, which makes it more susceptible to destruction by the proteosome. This enzyme's activity can also be reduced by phosphorylation by an AMP-activated protein kinase. Because this kinase is activated by AMP, which is produced when ATP is hydrolyzed, it follows that cholesterol synthesis is halted when ATP levels are low.

Plasma transport and regulation of absorption

See also: Blood lipidsCholesterol is only slightly soluble in water; it can dissolve and travel in the water-based bloodstream at exceedingly small concentrations. Since cholesterol is insoluble in blood, it is transported in the circulatory system within lipoproteins, complex discoidal particles which have an exterior composed of amphiphilic proteins and lipids whose outward-facing surfaces are water-soluble and inward-facing surfaces are lipid-soluble; triglycerides and cholesterol esters are carried internally. Phospholipids and cholesterol, being amphipathic, are transported in the surface monolayer of the lipoprotein particle.

In addition to providing a soluble means for transporting cholesterol through the blood, lipoproteins have cell-targeting signals that direct the lipids they carry to certain tissues. For this reason, there are several types of lipoproteins within blood called, in order of increasing density, chylomicrons, very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL). The more lipid and less protein a lipoprotein has, the less dense it is. The cholesterol within all the various lipoproteins is identical, although some cholesterol is carried as the "free" alcohol and some is carried as fatty acyl esters referred to as cholesterol esters. However, the different lipoproteins contain apolipoproteins, which serve as ligands for specific receptors on cell membranes. In this way, the lipoprotein particles are molecular addresses that determine the start- and endpoints for cholesterol transport.

Chylomicrons, the least dense type of cholesterol transport molecules, contain apolipoprotein B-48, apolipoprotein C, and apolipoprotein E in their shells. Chylomicrons are the transporters that carry fats from the intestine to muscle and other tissues that need fatty acids for energy or fat production. Cholesterol which is not used by muscles remains in more cholesterol-rich chylomicron remnants, which are taken up from the bloodstream by the liver.

VLDL molecules are produced by the liver and contain excess triacylglycerol and cholesterol that is not required by the liver for synthesis of bile acids. These molecules contain apolipoprotein B100 and apolipoprotein E in their shells. During transport in the bloodstream, the blood vessels cleave and absorb more triacylglycerol from IDL molecules, which contain an even higher percentage of cholesterol. The IDL molecules have two possible fates: Half are into metabolism by HTGL, taken up by the LDL receptor on the liver cell surfaces, and the other half continue to lose triacylglycerols in the bloodstream until they form LDL molecules, which have the highest percentage of cholesterol within them.

LDL molecules, therefore, are the major carriers of cholesterol in the blood, and each one contains approximately 1,500 molecules of cholesterol ester. The shell of the LDL molecule contains just one molecule of apolipoprotein B100, which is recognized by the LDL receptor in peripheral tissues. Upon binding of apolipoprotein B100, many LDL receptors become localized in clathrin-coated pits. Both the LDL and its receptor are internalized by endocytosis to form a vesicle within the cell. The vesicle then fuses with a lysosome, which has an enzyme called lysosomal acid lipase that hydrolyzes the cholesterol esters. Now within the cell, the cholesterol can be used for membrane biosynthesis or esterified and stored within the cell, so as to not interfere with cell membranes.

Synthesis of the LDL receptor is regulated by SREBP, the same regulatory protein as was used to control synthesis of cholesterol de novo in response to cholesterol presence in the cell. When the cell has abundant cholesterol, LDL receptor synthesis is blocked so new cholesterol in the form of LDL molecules cannot be taken up. On the converse, more LDL receptors are made when the cell is deficient in cholesterol. When this system is deregulated, many LDL molecules appear in the blood without receptors on the peripheral tissues. These LDL molecules are oxidized and taken up by macrophages, which become engorged and form foam cells. These cells often become trapped in the walls of blood vessels and contribute to artherosclerotic plaque formation. Differences in cholesterol homeostasis affect the development of early atherosclerosis (carotid intima-media thickness). These plaques are the main causes of heart attacks, strokes, and other serious medical problems, leading to the association of so-called LDL cholesterol (actually a lipoprotein) with "bad" cholesterol.

Also, HDL particles are thought to transport cholesterol back to the liver for excretion or to other tissues that use cholesterol to synthesize hormones in a process known as reverse cholesterol transport (RCT). Having large numbers of large HDL particles correlates with better health outcomes. In contrast, having small numbers of large HDL particles is independently associated with atheromatous disease progression within the arteries.

Metabolism, recycling and excretion

Cholesterol is susceptible to oxidation and easily forms oxygenated derivatives known as oxysterols. Three different mechanisms can form these; autoxidation, secondary oxidation to lipid peroxidation, and cholesterol-metabolizing enzyme oxidation. A great interest in oxysterols arose when they were shown to exert inhibitory actions on cholesterol biosynthesis. This finding became known as the “oxysterol hypothesis”. Additional roles for oxysterols in human physiology include their: participation in bile acid biosynthesis, function as transport forms of cholesterol, and regulation of gene transcription.

Cholesterol is oxidized by the liver into a variety of bile acids. These, in turn, are conjugated with glycine, taurine, glucuronic acid, or sulfate. A mixture of conjugated and nonconjugated bile acids, along with cholesterol itself, is excreted from the liver into the bile. Approximately 95% of the bile acids are reabsorbed from the intestines, and the remainder are lost in the feces. The excretion and reabsorption of bile acids forms the basis of the enterohepatic circulation, which is essential for the digestion and absorption of dietary fats. Under certain circumstances, when more concentrated, as in the gallbladder, cholesterol crystallises and is the major constituent of most gallstones. Although, lecithin and bilirubin gallstones also occur, but less frequently. Every day, up to 1 g of cholesterol enters the colon. This cholesterol originates from the diet, bile, and desquamated intestinal cells, and can be metabolized by the colonic bacteria. Cholesterol is mainly converted into coprostanol, a nonabsorbable sterol which is excreted in the feces. A cholesterol-reducing bacterium origin has been isolated from human feces.

Significance

Hypercholesterolemia

Main articles: hypercholesterolemia and lipid hypothesisAccording to the lipid hypothesis, abnormal cholesterol levels (hypercholesterolemia)—that is, higher concentrations of LDL and lower concentrations of functional HDL—are strongly associated with cardiovascular disease because these promote atheroma development in arteries (atherosclerosis). This disease process leads to myocardial infarction (heart attack), stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. Since higher blood LDL, especially higher LDL particle concentrations and smaller LDL particle size, contribute to this process more than the cholesterol content of the HDL particles, LDL particles are often termed "bad cholesterol" because they have been linked to atheroma formation. On the other hand, high concentrations of functional HDL, which can remove cholesterol from cells and atheroma, offer protection and are sometimes referred to as "good cholesterol". These balances are mostly genetically determined, but can be changed by body build, medications, food choices, and other factors.

Conditions with elevated concentrations of oxidized LDL particles, especially "small dense LDL" (sdLDL) particles, are associated with atheroma formation in the walls of arteries, a condition known as atherosclerosis, which is the principal cause of coronary heart disease and other forms of cardiovascular disease. In contrast, HDL particles (especially large HDL) have been identified as a mechanism by which cholesterol and inflammatory mediators can be removed from atheroma. Increased concentrations of HDL correlate with lower rates of atheroma progressions and even regression. A 2007 study pooling data on almost 900,000 subjects in 61 cohorts demonstrated that blood total cholesterol levels have an exponential effect on cardiovascular and total mortality, with the association more pronounced in younger subjects. Still, because cardiovascular disease is relatively rare in the younger population, the impact of high cholesterol on health is still larger in older people.

Elevated levels of the lipoprotein fractions, LDL, IDL and VLDL are regarded as atherogenic (prone to cause atherosclerosis). Levels of these fractions, rather than the total cholesterol level, correlate with the extent and progress of atherosclerosis. On the converse, the total cholesterol can be within normal limits, yet be made up primarily of small LDL and small HDL particles, under which conditions atheroma growth rates would still be high. In contrast, however, if LDL particle number is low (mostly large particles) and a large percentage of the HDL particles are large, then atheroma growth rates are usually low, even negative, for any given total cholesterol concentration. Recently, a post hoc analysis of the IDEAL and the EPIC prospective studies found an association between high levels of HDL cholesterol (adjusted for apolipoprotein A-I and apolipoprotein B) and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, casting doubt on the cardioprotective role of "good cholesterol".

Elevated cholesterol levels are treated with a strict diet consisting of low saturated fat, trans fat-free, low cholesterol foods, often followed by one of various hypolipidemic agents, such as statins, fibrates, cholesterol absorption inhibitors, nicotinic acid derivatives or bile acid sequestrants. Extreme cases have previously been treated with partial ileal bypass surgery, which has now been superseded by medication. Apheresis-based treatments are still used for very severe hyperlipidemias that are either unresponsive to treatment or require rapid lowering of blood lipids.

Multiple human trials using HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, known as statins, have repeatedly confirmed that changing lipoprotein transport patterns from unhealthy to healthier patterns significantly lowers cardiovascular disease event rates, even for people with cholesterol values currently considered low for adults. As a result, people with a history of cardiovascular disease may derive benefit from statins irrespective of their cholesterol levels, and in men without cardiovascular disease, there is benefit from lowering abnormally high cholesterol levels ("primary prevention"). Primary prevention in women is practiced only by extension of the findings in studies on men, since in women, none of the large statin trials has shown a reduction in overall mortality or in cardiovascular endpoints.

| Level mg/dL | Level mmol/L | Interpretation |

| < 200 | < 5.2 | Desirable level corresponding to lower risk for heart disease |

| 200–240 | 5.2–6.2 | Borderline high risk |

| > 240 | > 6.2 | High risk |

The 1987 report of National Cholesterol Education Program, Adult Treatment Panels suggests the total blood cholesterol level should be: < 200 mg/dL normal blood cholesterol, 200–239 mg/dL borderline-high, > 240 mg/dL high cholesterol. The American Heart Association provides a similar set of guidelines for total (fasting) blood cholesterol levels and risk for heart disease:

However, as today's testing methods determine LDL ("bad") and HDL ("good") cholesterol separately, this simplistic view has become somewhat outdated. The desirable LDL level is considered to be less than 100 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L), although a newer upper limit of 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) can be considered in higher-risk individuals based on some of the above-mentioned trials. A ratio of total cholesterol to HDL—another useful measure—of far less than 5:1 is thought to be healthier. Of note, typical LDL values for children before fatty streaks begin to develop is 35 mg/dL.

Total cholesterol is defined as the sum of HDL, LDL, and VLDL. Usually, only the total, HDL, and triglycerides are measured. For cost reasons, the VLDL is usually estimated as one-fifth of the triglycerides and the LDL is estimated using the Friedewald formula (or a variant): estimated LDL = − − . VLDL can be calculated by dividing total triglycerides by five. Direct LDL measures are used when triglycerides exceed 400 mg/dL. The estimated VLDL and LDL have more error when triglycerides are above 400 mg/dL.

Given the well-recognized role of cholesterol in cardiovascular disease, some studies have shown, surprisingly, an inverse correlation between cholesterol levels and mortality. A 2009 study of patients with acute coronary syndromes found an association of hypercholesterolemia with better mortality outcomes. In the Framingham Heart Study, in subjects over 50 years of age, they found an 11% increase overall and 14% increase in cardiovascular disease mortality per 1 mg/dL per year drop in total cholesterol levels. The researchers attributed this phenomenon to the fact that people with severe chronic diseases or cancer tend to have below-normal cholesterol levels. This explanation is not supported by the Vorarlberg Health Monitoring and Promotion Programme, in which men of all ages and women over 50 with very low cholesterol were increasingly likely to die of cancer, liver diseases, and mental diseases. This result indicates the low-cholesterol effect occurs even among younger respondents, contradicting the previous assessment among cohorts of older people that this is a proxy or marker for frailty occurring with age.

The vast majority of doctors and medical scientists consider that there is a link between cholesterol and atherosclerosis as discussed above; a small group of scientists, united in The International Network of Cholesterol Skeptics, questions the link.

Hypocholesterolemia

Abnormally low levels of cholesterol are termed hypocholesterolemia. Research into the causes of this state is relatively limited, but some studies suggest a link with depression, cancer, and cerebral hemorrhage. In general, the low cholesterol levels seem to be a consequence of an underlying illness, rather than a cause.

Cholesterol testing

| The examples and perspective in this section report US measures, whereas the measure in many places is mmol/L, into which they need to be converted, therefore the section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this section report US measures, whereas the measure in many places is mmol/L, into which they need to be converted, therefore the section, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new section report US measures, whereas the measure in many places is mmol/L, into which they need to be converted, therefore the section, as appropriate. (October 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The American Heart Association recommends testing cholesterol every five years for people aged 20 years or older.

A blood sample after 12-hour fasting is taken by a doctor, or a home cholesterol-monitoring device is used to determine a lipoprotein profile. This measures total cholesterol, LDL (bad) cholesterol, HDL (good) cholesterol, and triglycerides. It is recommended to test cholesterol at least every five years if a person has total cholesterol of 200 mg/dL or more, or if a man over age 45 or a woman over age 50 has HDL (good) cholesterol less than 40 mg/dL, or there are other risk factors for heart disease and stroke. (In different countries measurements are given in mg/dL or mmol/L; 1 mmol/L is 38.665 mg/dL.)

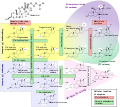

Interactive pathway map

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles.

[[File:

- The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "Statin_Pathway_WP430".

Cholesteric liquid crystals

Some cholesterol derivatives (among other simple cholesteric lipids) are known to generate the liquid crystalline "cholesteric phase". The cholesteric phase is, in fact, a chiral nematic phase, and it changes colour when its temperature changes. This makes cholesterol derivatives useful for indicating temperature in liquid crystal display thermometers and in temperature-sensitive paints.

See also

- Arcus senilis "Cholesterol ring" in the eyes

- Bile salts

- Cholesterol total synthesis

- Diet and heart disease

- Lieberman–Burchard test to detect cholesterol

- Lipid profile

- Niemann–Pick disease Type C

- Oxycholesterol

- Triglycerides

- Vertical Auto Profile

Additional images

-

Steroidogenesis, using cholesterol as building material

Steroidogenesis, using cholesterol as building material

-

Space-filling model of the Cholesterol molecule

Space-filling model of the Cholesterol molecule

-

Numbering of the steroid nuclei

Numbering of the steroid nuclei

References

- ^ "Safety (MSDS) data for cholesterol". Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- Emma Leah (2009). "Cholesterol". Lipidomics Gateway. doi:10.1038/lipidmaps.2009.3.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Pearson A, Budin M, Brocks JJ (2003). "Phylogenetic and biochemical evidence for sterol synthesis in the bacterium Gemmata obscuriglobus". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (26): 15352–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.2536559100. PMC 307571. PMID 14660793.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "High cholesterol levels by NHS". National Health Service. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- Olson RE (1998). "Discovery of the lipoproteins, their role in fat transport and their significance as risk factors". J. Nutr. 128 (2 Suppl): 439S – 443S. PMID 9478044.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - John S, Sorokin AV, Thompson PD (2007). "Phytosterols and vascular disease". Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 18 (1): 35–40. doi:10.1097/MOL.0b013e328011e9e3. PMID 17218830.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sadava D, Hillis DM, Heller HC, Berenbaum MR (2011). Life: The Science of Biology 9th Edition. San Francisco: Freeman. pp. 105–114. ISBN 1-4292-4646-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Yeagle PL (1991). "Modulation of membrane function by cholesterol". Biochimie. 73 (10): 1303–10. doi:10.1016/0300-9084(91)90093-G. PMID 1664240.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Haines TH (2001). "Do sterols reduce proton and sodium leaks through lipid bilayers?". Prog. Lipid Res. 40 (4): 299–324. doi:10.1016/S0163-7827(01)00009-1. PMID 11412894.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Incardona JP, Eaton S (2000). "Cholesterol in signal transduction". Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12 (2): 193–203. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(99)00076-9. PMID 10712926.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Pawlina W, Ross MW (2006). Histology: a text and atlas: with correlated cell and molecular biology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Wiliams & Wilkins. p. 230. ISBN 0-7817-5056-3.

- Smith LL (1991). "Another cholesterol hypothesis: cholesterol as antioxidant". Free Radic. Biol. Med. 11 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(91)90187-8. PMID 1937129.

- Christie, William (2003). Lipid analysis: isolation, separation, identification, and structural analysis of lipids. Ayr, Scotland: Oily Press. ISBN 0-9531949-5-7.

- ^ "USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 21" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- Jensen RG, Hagerty MM, McMahon KE (1 June 1978). "Lipids of human milk and infant formulas: a review" (PDF). Am J Clin Nutr. 31 (6): 990–1016. PMID 352132.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Behrman EJ, Gopalan V (2005). "Cholesterol and Plants". J. Chem. Educ. 82 (12): 1791. doi:10.1021/ed082p1791.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Ostlund RE, Racette, SB, and Stenson WF (2003). "Inhibition of cholesterol absorption by phytosterol-replete wheat germ compared with phytosterol-depleted wheat germ". Am J Clin Nutr. 77 (6): 1385–1589. PMID 12791614.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - European Food Safety Authority, Journal (2010). "Scientific opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to plant sterols and plant stanols and maintenance of normal blood cholesterol concentrations".

- Demonty, I (2009 Feb). "Continuous dose-response relationship of the LDL-cholesterol-lowering effect of phytosterol intake". The Journal of nutrition. 139 (2): 271–84. doi:10.3945/jn.108.095125. PMID 19091798.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Weingärtner O, Ulrich C, Lütjohann D, Ismail K, Schirmer SH, Vanmierlo T, Böhm M, Laufs U (2011). "Differential effects on inhibition of cholesterol absorption by plant stanol and plant sterol esters in apoE-/- mice". Cardiovasc Res. 90 (3): 484–92. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvr020. PMC 3096304. PMID 21257611.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Weingärtner O, Böhm M, Laufs U (2009). "Controversial role of plant sterol esters in the management of hypercholesterolaemia". Eur. Heart J. 30 (4): 404–9. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn580. PMC 2642922. PMID 19158117.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ""Health effects of trans fatty acids" (review article)". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 66: 1006S–1010S.

- "Dietary Guidlines for Americans 2005" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- Le Fanu, James (2000). The rise and fall of modern medicine. New York, NY: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-0732-1.

- Campbell TC, Campbell TM (2005). The China Study: the most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted and the startling implications for diet, weight loss and long-term health. Benbella Books. ISBN 1-932100-38-5.

- Rhodes, Carl; Stryer, Lubert; Tasker, Roy (1995). Biochemistry (4th ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. pp. 280, 703. ISBN 0-7167-2009-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Espenshade PJ, Hughes AL (2007). "Regulation of sterol synthesis in eukaryotes". Annu. Rev. Genet. 41: 401–27. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130315. PMID 17666007.

- Brown MS, Goldstein JL (1997). "The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor". Cell. 89 (3): 331–40. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80213-5. PMID 9150132.

- ^ Tymoczko, John L.; Stryer Berg Tymoczko; Stryer, Lubert; Berg, Jeremy Mark (2002). Biochemistry. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. pp. 726–727. ISBN 0-7167-4955-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Weingärtner O, Pinsdorf T, Rogacev KS, Blömer L, Grenner Y, Gräber S, Ulrich C, Girndt M, Böhm M, Fliser D, Laufs U, Lütjohann D, Heine GH (2010). Federici, Massimo (ed.). "The relationships of markers of cholesterol homeostasis with carotid intima-media thickness". PLoS ONE. 5 (10): e13467. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013467. PMC 2956704. PMID 20976107.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Lewis GF, Rader DJ (2005). "New insights into the regulation of HDL metabolism and reverse cholesterol transport". Circ. Res. 96 (12): 1221–32. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000170946.56981.5c. PMID 15976321.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Gordon DJ, Probstfield JL, Garrison RJ, Neaton JD, Castelli WP, Knoke JD, Jacobs DR, Bangdiwala S, Tyroler HA (1989). "High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Four prospective American studies". Circulation. 79 (1): 8–15. PMID 2642759.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kandutsch AA, Chen HW, Heiniger HJ (1978). "Biological activity of some oxygenated sterols". Science. 201 (4355): 498–501. doi:10.1126/science.663671. PMID 663671.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Russell DW (2000). "Oxysterol biosynthetic enzymes". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1529 (1–3): 126–35. doi:10.1016/S1388-1981(00)00142-6. PMID 11111082.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Javitt NB (1994). "Bile acid synthesis from cholesterol: regulatory and auxiliary pathways". FASEB J. 8 (15): 1308–11. PMID 8001744.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Wolkoff AW, Cohen DE (2003). "Bile acid regulation of hepatic physiology: I. Hepatocyte transport of bile acids". Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 284 (2): G175–9. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00409.2002. PMID 12529265.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Marschall HU, Einarsson C (2007). "Gallstone disease". J. Intern. Med. 261 (6): 529–42. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01783.x. PMID 17547709.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Gérard P, Lepercq P, Leclerc M, Gavini F, Raibaud P, Juste C (2007). "Bacteroides sp. strain D8, the first cholesterol-reducing bacterium isolated from human feces". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73 (18): 5742–9. doi:10.1128/AEM.02806-06. PMC 2074900. PMID 17616613.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Brunzell JD, Davidson M, Furberg CD, Goldberg RB, Howard BV, Stein JH, Witztum JL (2008). "Lipoprotein management in patients with cardiometabolic risk: consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation". Diabetes Care. 31 (4): 811–22. doi:10.2337/dc08-9018. PMID 18375431.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Durrington P (2003). "Dyslipidaemia". Lancet. 362 (9385): 717–31. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14234-1. PMID 12957096.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R (2007). "Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths". Lancet. 370 (9602): 1829–39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. PMID 18061058.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Final Report" (PDF). National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- van der Steeg WA, Holme I, Boekholdt SM, Larsen ML, Lindahl C, Stroes ES, Tikkanen MJ, Wareham NJ, Faergeman O, Olsson AG, Pedersen TR, Khaw KT, Kastelein JJ (2008). "High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein particle size, and apolipoprotein A-I: significance for cardiovascular risk: the IDEAL and EPIC-Norfolk studies". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 51 (6): 634–42. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.060. PMID 18261682.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "How Can I Lower High Cholesterol" (PDF). American Heart Association. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Good Cholesterol Foods". Good Cholesterol Foods. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 67: Lipid modification. London, 2008.

- Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group (2002). "MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial". Lancet. 360 (9326): 7–22. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3. PMID 12114036.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, Isles CG, Lorimer AR, MacFarlane PW, McKillop JH, Packard CJ (1995). "Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group". N. Engl. J. Med. 333 (20): 1301–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. PMID 7566020.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grundy SM (2007). "Should women be offered cholesterol lowering drugs to prevent cardiovascular disease? Yes". BMJ. 334 (7601): 982–982. doi:10.1136/bmj.39202.399942.AD. PMC 1867899. PMID 17494017.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Kendrick M (2007). "Should women be offered cholesterol lowering drugs to prevent cardiovascular disease? No". BMJ. 334 (7601): 983–983. doi:10.1136/bmj.39202.397488.AD. PMC 1867901. PMID 17494018.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - , (1988). "Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. The Expert Panel". Arch. Intern. Med. 148 (1): 36–69. doi:10.1001/archinte.148.1.36. PMID 3422148.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has numeric name (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - "Cholesterol". American Heart Association. 17 November 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "About cholesterol" – American Heart Association

- Warnick GR, Knopp RH, Fitzpatrick V, Branson L (1990). "Estimating low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by the Friedewald equation is adequate for classifying patients on the basis of nationally recommended cutpoints". Clin. Chem. 36 (1): 15–9. PMID 2297909.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19645040, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19645040instead. - Anderson KM, Castelli WP, Levy D (1987). "Cholesterol and mortality. 30 years of follow-up from the Framingham study". JAMA. 257 (16): 2176–80. doi:10.1001/jama.257.16.2176. PMID 3560398.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ulmer H, Kelleher C, Diem G, Concin H (2004). "Why Eve is not Adam: prospective follow-up in 149650 women and men of cholesterol and other risk factors related to cardiovascular and all-cause mortality". J Women's Health (Larchmt). 13 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1089/154099904322836447. PMID 15006277.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Daniel Steinberg (2007). The Cholesterol Wars: The Cholesterol Skeptics vs the Preponderance of Evidence. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-373979-9.

- Uffe Ravnskov (2000). The Cholesterol Myths : Exposing the Fallacy that Saturated Fat and Cholesterol Cause Heart Disease. New Trends Publishing, Incorporated. ISBN 0-96708-970-0.

- "How To Get Your Cholesterol Tested". American Heart Association. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

- Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults US National Institutes of Health Adult Treatment Panel III

- Aspects of fat digestion and metabolism – UN/WHO Report 1994

- American Heart Association – "About Cholesterol"

| Cholestanes, membrane lipids: sterols | |

|---|---|

| Cholesterol and steroid metabolic intermediates | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mevalonate pathway |

| ||||||||||

| Non-mevalonate pathway | |||||||||||

| To Cholesterol | |||||||||||

| From Cholesterol to Steroid hormones |

| ||||||||||

| Nonhuman |

| ||||||||||

| Cardiovascular disease (vessels) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arteries, arterioles and capillaries | |||||||||

| Veins |

| ||||||||

| Arteries or veins | |||||||||

| Blood pressure |

| ||||||||

Categories: