This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Andrewman327 (talk | contribs) at 00:52, 7 March 2013 (Reverted edit(s) by 50.128.188.117 identified as test/vandalism using STiki). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:52, 7 March 2013 by Andrewman327 (talk | contribs) (Reverted edit(s) by 50.128.188.117 identified as test/vandalism using STiki)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Coretta Scott King | |

|---|---|

King speaking in Abuja, Nigeria in January 2003, at the age of 75

. King speaking in Abuja, Nigeria in January 2003, at the age of 75

. | |

| Born | Coretta Scott Smith James (1927-04-27)April 27, 1927 Heiberger, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | January 30, 2006(2006-01-30) (aged 78) Playas de Rosarito, Mexico |

| Occupation(s) | Civil rights, women's rights, gay rights, human rights, equal rights activist, author |

| Spouse | Martin Luther King, Jr. |

| Children | Yolanda King (deceased) Martin Luther King III Dexter Scott King Bernice King |

| Parent(s) | Obadiah Scott Bernice McMurray Scott |

Coretta Scott King (April 27, 1927 – January 30, 2006) was an American author, activist, and civil rights leader. The widow of Martin Luther King, Jr., Coretta Scott King helped lead the African-American Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.

Mrs. King played a prominent role in the years after her husband's 1968 assassination when she took on the leadership of the struggle for racial equality herself and became active in the Women's Movement and the LGBT rights movement.

Childhood and education

Coretta Scott King was the third of four children born to Obadiah "Obe" Scott (1899–1998) and Bernice McMurray Scott (1904–1996) in Marion, Alabama. She had an older sister named Edythe Scott Bagley (1924–2011) an older sister named Eunice who did not survive childhood, and a younger brother named Obadiah Leonard, born in 1930. According to a DNA analysis, she descended, mainly, from people of Mende people of Sierra Leone. The Scott family had owned a farm since the American Civil War, but were not particularly wealthy. During the Great Depression the Scott children picked cotton to help earn money. Obe was the first black person in their neighborhood to own a truck. He had a barber shop in their home. He also owned a lumber mill, which was burned down by white neighbors.

Though lacking formal education themselves, Coretta Scott's parents intended for all of their children to be educated. Coretta quoted her mother as having said, "My children are going to college, even if it means I only have but one dress to put on." The Scott children attended a one room elementary school 5 miles (8 km) from their home and were later bused to Lincoln Normal School, which despite being 9 mi (14 km) from their home, was the closest black high school in Marion, Alabama, due to racial segregation in schools. The bus was driven by Coretta's mother Bernice, who bused all the local black teenagers.

Coretta Scott graduated valedictorian of Lincoln Normal School in 1945 where she played trumpet and piano, sang in the chorus, and participated in school musicals and enrolled at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Her older sister Edythe already attended Antioch as part of the Antioch Program for Interracial Education, which recruited non-white students and gave them full scholarships in an attempt to diversify the historically white campus. Coretta said of her first college:

Antioch had envisioned itself as a laboratory in democracy, but had no black students. (Edythe) became the first African American to attend Antioch on a completely integrated basis, and was joined by two other black female students in the fall of 1943. Pioneering is never easy, and all of us who followed my sister at Antioch owe her a great debt of gratitude.

Coretta studied music with Walter Anderson, the first non-white chair of an academic department in a historically white college. She also became politically active, due largely to her experience of racial discrimination by the local school board. She became active in the nascent civil rights movement; she joined the Antioch chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the college's Race Relations and Civil Liberties Committees. The board denied her request to perform her second year of required practice teaching at Yellow Springs public schools, for her teaching certificate Coretta Scott appealed to the Antioch College administration, which was unwilling or unable to change the situation in the local school system and instead employed her at the college's associated laboratory school for a second year.

Coretta transferred out of Antioch when she won a scholarship to the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. It was while studying singing at that school with Marie Sundelius that she met Martin Luther King, Jr. In her early life Coretta was as well known as a singer as she was as a civil rights activist, and often incorporated music into her civil rights work. In 1964, the Time profile of Martin Luther King, Jr., when he was chosen as Time's "Man of the Year", referred to her as "a talented young soprano."

Family life

Coretta Scott and Martin Luther King, Jr., were married on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of her mother's house; the ceremony was performed by Martin Jr.'s father, Martin Luther King, Sr.. Coretta had the vow to obey her husband removed from the ceremony, which was unusual for the time. After completing her degree in voice and piano at the New England Conservatory, she moved with her husband to Montgomery, Alabama, in September 1954. Mrs. King recalled: "After we married, we moved to Montgomery, Alabama, where my husband had accepted an invitation to be the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Before long, we found ourselves in the middle of the Montgomery bus boycott, and Martin was elected leader of the protest movement. As the boycott continued, I had a growing sense that I was involved in something so much greater than myself, something of profound historic importance. I came to the realization that we had been thrust into the forefront of a movement to liberate oppressed people, not only in Montgomery but also throughout our country, and this movement had worldwide implications. I felt blessed to have been called to be a part of such a noble and historic cause."

The Kings had four children:

- Yolanda Denise King (November 17, 1955 – May 15, 2007)

- Martin Luther King III (October 23, 1957 in Montgomery, Alabama)

- Dexter Scott King (January 30, 1961 in Atlanta, Georgia)

- Bernice Albertine King (March 28, 1963 in Atlanta, Georgia)

All four children later followed in their parents' footsteps as civil rights activists.

Civil rights movement

Coretta Scott King played an extremely important role in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Martin wrote of her that, "I am indebted to my wife Coretta, without whose love, sacrifices, and loyalty neither life nor work would bring fulfillment. She has given me words of consolation when I needed them and a well-ordered home where Christian love is a reality." However, Martin and Coretta did conflict over her public role in the movement. Martin wanted Coretta to focus on raising their four children, while Coretta wanted to take a more public leadership role.

Coretta Scott King took part in the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955 and took an active role in advocating for civil rights legislation. Most prominently, perhaps, she worked hard to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Not long after her husband's assassination in 1968, Coretta approached the African-American entertainer and activist Josephine Baker to take her husband's place as leader of The Civil Rights Movement. After many days of thinking it over Baker declined, stating that her twelve adopted children (known as the "rainbow tribe") were "...too young to lose their mother". Shortly after that Mrs. King decided to take the helm of the movement herself.

Coretta Scott King broadened her focus to include women's rights, LGBT rights, economic issues, world peace, and various other causes. As early as December 1968, she called for women to "unite and form a solid block of women power to fight the three great evils of racism, poverty and war", during a Solidarity Day speech.

As leader of the movement, Mrs. King founded the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta. She served as the center's president and CEO from its inception until she passed the reins of leadership to son Dexter Scott King.

She published her memoirs, My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1969.

Coretta Scott King was also under surveillance by the Federal Bureau of Investigation from 1968 until 1972. Her husband's activities had been monitored during his lifetime. Documents obtained by a Houston, Texas television station show that the FBI worried that Coretta Scott King would "tie the anti-Vietnam movement to the civil rights movement." A spokesman for the King family said that they were aware of the surveillance, but had not realized how extensive it was.

Later life

Every year after the assassination of her husband in 1968, Coretta attended a commemorative service at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta to mark his birthday on January 15. She fought for years to make it a national holiday. Murray M. Silver, an Atlanta attorney, made the appeal at the services on January 14, 1979. Coretta Scott King later confirmed that it was the "...best, most productive appeal ever..." Coretta Scott King was finally successful in this in 1986, when Martin Luther King, Jr. Day was made a federal holiday.

Coretta Scott King attended the state funeral of Lyndon B. Johnson in 1973, as a very close friend of the former president.

In 1979 and 1980 Dr. Noel Erskine and Mrs. King co-taught a class on "The Theology of Martin Luther King, Jr." at the Candler School of Theology (Emory University).

When President Ronald Reagan signed legislation establishing Martin Luther King Day, she was at the event.

She became vegan in the last 10 years of her life.

Opposition to apartheid

During the 1980s, Coretta Scott King reaffirmed her long-standing opposition to apartheid, participating in a series of sit-in protests in Washington, D.C. that prompted nationwide demonstrations against South African racial policies.

In 1986, she traveled to South Africa and met with Winnie Mandela, while Mandela's husband Nelson Mandela was still a political prisoner in Pollsmoor Prison after being transferred from Robben Island in 1982. She declined invitations from Pik Botha and moderate Zulu chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi. Upon her return to the United States, she urged Reagan to approve economic sanctions against South Africa.

Peacemaking

Coretta Scott King was a long-time advocate for world peace. Author Michael Eric Dyson has called her "an earlier and more devoted pacifist than her husband." Although Mrs. King would object to the term "pacifism"; she was an advocate of non-violent direct action to achieve social change. In 1957, Mrs. King was one of the founders of The Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (now called Peace Action).

Mrs. King was vocal in her opposition to capital punishment and the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

LGBT equality

On April 1, 1998 at the Palmer House Hilton in Chicago, Mrs. King called on the civil rights community to join in the struggle against homophobia and anti-gay bias. "Homophobia is like racism and anti-Semitism and other forms of bigotry in that it seeks to dehumanize a large group of people, to deny their humanity, their dignity and personhood", she stated. "This sets the stage for further repression and violence that spread all too easily to victimize the next minority group."

In a speech in November 2003 at the opening session of the 13th annual Creating Change Conference, organized by the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, Coretta Scott King made her now famous appeal linking the Civil Rights Movement to LGBT rights: "I still hear people say that I should not be talking about the rights of lesbian and gay people. ... But I hasten to remind them that Martin Luther King Jr. said, 'Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.' I appeal to everyone who believes in Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream, to make room at the table of brotherhood and sisterhood for lesbian and gay people."

Coretta Scott King's support of LGBT rights was strongly criticized by some African-American pastors. She called her critics "misinformed" and said that Martin Luther King's message to the world was one of equality and inclusion.

In 2003, she invited the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force to take part in observances of the 40th anniversary of the March on Washington and Martin Luther King's I Have a Dream speech. It was the first time that an LGBT rights group had been invited to a major event of the African-American community.

On March 23, 2004, she told an audience at Richard Stockton College in Pomona, New Jersey, that same-sex marriage is a civil rights issue. She denounced a proposed amendment advanced by President George W. Bush to the United States Constitution that would ban equal marriage rights for same-sex couples. In her speech King also criticized a group of black pastors in her home state of Georgia for backing a bill to amend that state's constitution to block gay and lesbian couples from marrying. Scott King is quoted as saying "Gay and lesbian people have families, and their families should have legal protection, whether by marriage or civil union. A constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriages is a form of gay bashing and it would do nothing at all to protect traditional marriage."

The King Center

Established in 1968 by Coretta Scott King, The King Center is the official memorial dedicated to the advancement of the legacy and ideas of Martin Luther King, Jr., leader of a nonviolent movement for justice, equality and peace. She handed the reins as CEO and president of the King Center down to her son, Dexter Scott King, who still runs the center today.

Final days

By the end of her 77th year, Coretta began experiencing health problems. Her husband's former secretary, Dora McDonald, assisted her part-time in this period. Hospitalized in April 2005, a month after speaking in Selma at the 40th anniversary of the Selma Voting Rights Movement, she was diagnosed with a heart condition and was discharged on her 78th and final birthday. Later, she suffered several small strokes. On August 16, 2005, she was hospitalized after suffering a stroke and a mild heart attack. Initially, she was unable to speak or move her right side. She was released from Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta on September 22, 2005, after regaining some of her speech and continued physiotherapy at home. Due to continuing health problems, Mrs. King cancelled a number of speaking and traveling engagements throughout the remainder of 2005. On January 14, 2006, Coretta made her last public appearance in Atlanta at a dinner honoring her husband's memory.

Death

Coretta Scott King died in the late evening of January 30, 2006, at a rehabilitation center in Rosarito Beach, Mexico, In the Oasis Hospital where she was undergoing holistic therapy for her stroke and advanced stage ovarian cancer. The main cause of her death is believed to be respiratory failure due to complications from ovarian cancer. The clinic at which she died was called the Hospital Santa Monica, but was licensed as Clinica Santo Tomas. Newspaper reports indicated that it was not legally licensed to "perform surgery, take X-rays, perform laboratory work or run an internal pharmacy, all of which it was doing." It was also founded, owned, and operated by San Diego resident and highly controversial alternative medicine figure Kurt Donsbach. Days after Mrs. King's death, the Baja California, Mexico, state medical commissioner, Dr. Francisco Vera, shut down the clinic.

Funeral

Over 14,000 people gathered for Coretta Scott King's eight-hour funeral at the New Birth Missionary Baptist Church in Lithonia, Georgia on February 7, 2006 where daughter Bernice King, who is an elder at the church, eulogized her mother. The megachurch, whose sanctuary seats 10,000, was better able to handle the expected massive crowds than Ebenezer Baptist Church, of which Mrs. King was a member since the early 1960s and which was the site of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s funeral in 1968.

U.S. Presidents George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George H.W. Bush, Jimmy Carter, and their wives attended. The Ford family was absent due to the illness of President Ford (who himself died later that year). Former First Lady Barbara Bush had a previous engagement and also did not attend. Numerous other prominent political and civil rights leaders, including then-U.S. senator Barack Obama, attended the televised service.

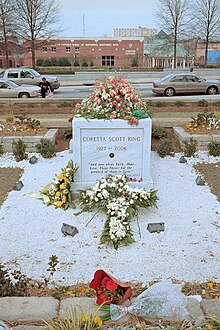

Mrs. King was interred in a temporary mausoleum on the grounds of the King Center until a permanent place next to her husband's remains could be built. She had expressed to family members and others that she wanted her remains to lie next to her husband's at the King Center. On November 20, 2006 the new mausoleum containing both the bodies of Dr. and Mrs King was unveiled in front of friends and family. It is the third resting place of Martin Luther King.

Funeral oration

President Jimmy Carter and Rev. Joseph Lowery provided funeral orations. With President George W. Bush seated a few feet away, Rev. Lowery, referencing Coretta's vocal opposition to the Iraq War, noted the failure to find weapons of mass destruction in Iraq:

"She deplored the terror inflicted by our smart bombs on missions way afar. . . . We know now there were no weapons of mass destruction over there. But Coretta knew, and we knew, that there are weapons of misdirection right down here. Millions without health insurance. Poverty abounds. For war, billions more, but no more for the poor."

President Carter, referencing Coretta's lifelong struggle for civil rights, noted that her family had been the target of secret government wiretapping. Their somewhat controversial comments were met with thunderous applause and standing ovations.

Recognition and tributes

Coretta Scott King was the recipient of various honors and tributes both before and after her death. She received honorary degrees from many institutions, including Princeton University, Duke University, and Bates College. She was honored by both of her alma maters in 2004, receiving a Horace Mann Award from Antioch College and an Outstanding Alumni Award from the New England Conservatory of Music.

In 1970, the American Library Association began awarding a medal named for Coretta Scott King to outstanding African-American writers and illustrators of children's literature.

In 1978, Women's Way awarded King with their first Lucretia Mott Award for showing a dedication to the advancement of women and justice similar to Lucretia Mott's.

Many individuals and organizations paid tribute to Scott King following her death, including U.S. President George W. Bush, the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, the Human Rights Campaign, the National Black Justice Coalition, her alma mater Antioch College.

In 1997, Coretta Scott King was the recipient of the Academy of Achievement's Golden Plate Award.

In 2004, Coretta Scott King was awarded the prestigious Gandhi Peace Prize by the Government of India.

In 2006, the Jewish National Fund, the organization that works to plant trees in Israel, announced the creation of the Coretta Scott King forest in the Galilee region of Northern Israel, with the purpose of "perpetuating her memory of equality and peace", as well as the work of her husband. When she learned about this plan, King wrote to Israel's parliament:

- "On April 3, 1968, just before he was killed, Martin delivered his last public address. In it he spoke of the visit he and I made to Israel. Moreover, he spoke to us about his vision of the Promised Land, a land of justice and equality, brotherhood and peace. Martin dedicated his life to the goals of peace and unity among all peoples, and perhaps nowhere in the world is there a greater appreciation of the desirability and necessity of peace than in Israel."

In 2007, The Coretta Scott King Young Women's Leadership Academy (CSKYWLA) was opened in Atlanta, Georgia. At its inception, the school served girls in grade 6 with plans for expansion to grade 12 by 2014. CSKYWLA is a public school in the Atlanta Public Schools system. Among the staff and students, the acronym for the school's name, CSKYWLA (pronounced "see-skee-WAH-lah"), has been coined as a protologism to which this definition has given – "to be empowered by scholarship, non-violence, and social change." The school is currently under the leadership of Melody Morgan (Principal) and April Patton (Dean of Academics).

Super Bowl XL was dedicated to King and Rosa Parks. Both were memorialized with a moment of silence during the pregame ceremonies. The children of both Parks and King then helped Tom Brady with the ceremonial coin toss. In addition two choirs representing the states of Georgia (King's home state) and Alabama (Park's home state) accompanied Dr. John, Aretha Franklin and Aaron Neville in the singing the National Anthem.

She was inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame in 2009.

Congressional resolutions

Upon the news of her death, moments of reflection, remembrance, and mourning began around the world. In the United States Senate, Majority Leader Bill Frist presented Senate Resolution 362 on behalf of all U.S. Senators, with the afternoon hours filled with respectful tributes throughout the U.S. Capitol.

On August 31, 2006 following a moment of silence in memoriam to the death of Scott King, the United States House of Representatives presented House Resolution 655 in honor of her legacy. In an unusual action, the resolution included a grace period of five days in which further comments could be added to it.

References

- ^ "Coretta Scott King". Women's History. Gale Virtual Reference Library.

- http://www.africanancestry.com/blog/category/reveals/ African ancestries block Legendary Leaders and Ancestry

- ^ King, Coretta Scott (Fall 2004). "Address, Antioch Reunion 2004". The Antiochian. Archived from the original on 2007-05-01. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- "Coretta Scott King Dies at 78". ABC News. January 31, 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- "Never Again Where He Was". Time Magazine. January 3, 1964. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Biography and Video Interview of Coretta Scott King at Academy of Achievement.

- Josephine Baker and Joe Bouillon, Josephine. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1977.

- Pappas, Heather. "Coretta Scott King". Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- "FBI spied on Coretta Scott King, files show". The Los Angeles Times. August 31, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- "A King among men: Martin Luther King Jr.'s son blazes his own trail - Dexter Scott King". Vegetarian Times. 1995.

- Reynolds, Barbara A. (February 4, 2006). "The Real Coretta Scott King". The Washington Post.

- "Coretta Scott King". The Daily Telegraph. January 31, 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- Dyson, Michael Eric, I May Not Get There With You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr., pg. 64

- Coretta Scott King, Encyclopedia of Alabama

- ^ Terkel, Amanda (2011-01-19) Lawmakers Press Pentagon Official On MLK War Claim, Huffington Post

- Coretta Scott King: civil rights activist

- "Welcome". The King Center. n/a. Archived from the original on 2007-09-09. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Dewan, Shaila. "Dora E. McDonald, 81, Secretary to Martin Luther King in '60s," New York Times. January 15, 2007.

- "Coretta. Scott King dead at 78". The Associated Press. January 31, 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- "King had Paralysis and Cancer". The Associated Press. January 31, 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- "Clinic, founder operate outside norm". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. February 1, 2006.

- Barrett, Stephen (last revised September 10, 2007). "The Shady Activities of Kurt Donbach". Quackwatch. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - McKinley, James C. (February 4, 2006). "Mexico Closes Alternative Care Clinic Where Mrs. King Died". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- How He Did It

- King Memorials Into the Night

- McNamara, Melissa (2006-02-07) 'She Is Deeply Missed', CBS News

- "Alumni Profile: Coretta Scott King '54, '71 hon. D.M." New England Conservatory of Music. n/a. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "The Coretta Scott King Book Awards for Authors and Illustrators". American Library Association. n/a. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Bush, George W. (January 31, 2006). "State of the Union". The White House. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- "Task Force mourns death of Coretta Scott King". National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. January 31, 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- "Coretta Scott King Leaves Behind Legacy of the Everlasting Pursuit of Justice". Human Rights Campaign. January 31, 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- "Leader Passes Quietly into the Night: Coretta Scott King Dies at 78". National Black Justice Coalition. January 31, 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ""We have lost a great American and a great Antiochian....": Coretta Scott King's death mourned by the Antioch Community". Antioch College. January 31, 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-08-24. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- JNF Website.

- "Inductees". Alabama Women's Hall of Fame. State of Alabama. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

28. ^Silver, Murray M., "Daddy King and Me: Memories of the Forgotten Father of the Civil Rights Movement", (Continental Shelf Publishing, 2009)

External links

- Coretta Scott King's oral history video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

- Coretta Scott King's political donations

- About.com Profile of Coretta Scott King, Human Rights Advocate

- Coretta Scott King entry from African American Lives – OUP Blog

- A King Among Men (King family vegetarianism)

- Coretta Scott King Center at Antioch College

- King Center Founder's Message

- Coretta Scott King Funeral Program (PDF)

- Coretta Scott King panel eyes plan by year's end

- Coretta Scott King entry in the Encyclopedia of Alabama

- Obituary in the Atlanta Journal Constitution

- Coretta Scott King at Find-A-Grave

- Coretta Scott King – slideshow by Life magazine

| Civil rights movement (1954–1968) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events (timeline) |

| ||||||||

| Activist groups |

| ||||||||

| Activists |

| ||||||||

| By region | |||||||||

| Movement songs | |||||||||

| Influences | |||||||||

| Related |

| ||||||||

| Legacy |

| ||||||||

| Noted historians | |||||||||

| Alabama Women's Hall of Fame | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Inductees to the National Women's Hall of Fame | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

- 1927 births

- 2006 deaths

- American people of Sierra Leonean descent

- 20th-century African-American activists

- African-American Christians

- African-American women activists

- African Americans' rights activists

- American anti–nuclear weapons activists

- American Christian pacifists

- American feminists

- American vegans

- Antioch College alumni

- Baptists from the United States

- Burials in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Cancer deaths in Mexico

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Deaths from ovarian cancer

- International opponents of apartheid in South Africa

- LGBT rights activists from the United States

- Martin Luther King family

- New England Conservatory alumni

- Nonviolence advocates

- People from Perry County, Alabama

- People from Yellow Springs, Ohio

- Recipients of the Gandhi Peace Prize

- People of Mende descent