This is an old revision of this page, as edited by DigbyDalton (talk | contribs) at 23:38, 7 October 2013 (Unsubstantiated statement extremely hard to believe). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 23:38, 7 October 2013 by DigbyDalton (talk | contribs) (Unsubstantiated statement extremely hard to believe)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)"IPCC" redirects here. For other uses, see IPCC (disambiguation).

| Established | 1988 |

|---|---|

| Type | Panel |

| Legal status | Active |

| Website | www |

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is a scientific intergovernmental body, set up at the request of member governments. It was first established in 1988 by two United Nations organizations, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and later endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly through Resolution 43/53. Its mission is to provide comprehensive scientific assessments of current scientific, technical and socio-economic information worldwide about the risk of climate change caused by human activity, its potential environmental and socio-economic consequences, and possible options for adapting to these consequences or mitigating the effects. It is chaired by Rajendra K. Pachauri.

Thousands of scientists and other experts contribute to writing and reviewing reports, which are reviewed by representatives from all the governments, with a Summary for Policymakers being subject to line-by-line approval by all participating governments. Typically this involves the governments of more than 120 countries.

The IPCC does not carry out its own original research, nor does it do the work of monitoring climate or related phenomena itself. A main activity of the IPCC is publishing special reports on topics relevant to the implementation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), an international treaty that acknowledges the possibility of harmful climate change. Implementation of the UNFCCC led eventually to the Kyoto Protocol. The IPCC bases its assessment mainly on peer reviewed and published scientific literature. Membership of the IPCC is open to all members of the WMO and UNEP.

The IPCC provides an internationally accepted authority on climate change, producing reports which have the agreement of leading climate scientists and the consensus of participating governments. It has provided authoritative policy advice with far-reaching implications for economics and lifestyles. Governments have been slow to implement the advice. The 2007 Nobel Peace Prize was shared, in two equal parts, between the IPCC and Al Gore.

Aims

The principles that the IPCC operates under are set out in the relevant WMO Executive Council and UNEP Governing Council resolutions and decisions, as well as on actions in support of the UNFCCC process.

The aims of the IPCC are to assess scientific information relevant to:

- Human-induced climate change,

- The impacts of human-induced climate change,

- Options for adaptation and mitigation.

Operations

The chair of the IPCC is Rajendra K. Pachauri, elected in May 2002. The previous chair was Robert Watson. The chair is assisted by an elected bureau including vice-chairs, working group co-chairs and a secretariat.

The IPCC Panel is composed of representatives appointed by governments and organizations. Participation of delegates with appropriate expertise is encouraged. Plenary sessions of the IPCC and IPCC Working groups are held at the level of government representatives. Non Governmental and Intergovernmental Organizations may be allowed to attend as observers. Sessions of the IPCC Bureau, workshops, expert and lead authors meetings are by invitation only. Attendance at the 2003 meeting included 350 government officials and climate change experts. After the opening ceremonies, closed plenary sessions were held. The meeting report states there were 322 persons in attendance at Sessions with about seven-eighths of participants being from governmental organizations.

There are several major groups:

- IPCC Panel: Meets in plenary session about once a year and controls the organization's structure, procedures, and work programme. The Panel is the IPCC corporate entity.

- Chair: Elected by the Panel.

- Secretariat: Oversees and manages all activities. Supported by UNEP and WMO.

- Bureau: Elected by the Panel. Chaired by the Chair. 30 members include IPCC Vice-Chairs, Co-Chairs and Vice-Chairs of Working Groups and Task Force.

- Working Groups: Each has two Co-Chairs, one from the developed and one from developing world, and a technical support unit.

- Working Group I: Assesses scientific aspects of the climate system and climate change. Co-Chairs: Thomas Stocker, Dahe/bio|Dahe Qin

- Working Group II: Assesses vulnerability of socio-economic and natural systems to climate change, consequences, and adaptation options. Co-Chairs: Chris Field and Vicente Barros

- Working Group III: Assesses options for limiting greenhouse gas emissions and otherwise mitigating climate change. Co-Chairs: Ottmar Edenhofer, Youba Sokona and Ramon Pichs-Madruga

- Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories

The IPCC receives funding from UNEP, WMO, and its own Trust Fund for which it solicits contributions from governments. Its secretariat is hosted by the WMO, in Geneva.

Assessment reports

| Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

|---|

|

| IPCC Assessment Reports |

| IPCC Special Reports |

The IPCC has published four comprehensive assessment reports reviewing the latest climate science, as well as a number of special reports on particular topics. These reports are prepared by teams of relevant researchers selected by the Bureau from government nominations. Drafts of these reports are made available for comment in open review processes to which anyone may contribute.

The IPCC published its first assessment report in 1990, a supplementary report in 1992, a second assessment report (SAR) in 1995, and a third assessment report (TAR) in 2001. A fourth assessment report (AR4) was released in 2007 and a fifth is due to be issued in 2014.

Each assessment report is in three volumes, corresponding to Working Groups I, II and III. Unqualified, "the IPCC report" is often used to mean the Working Group I report, which covers the basic science of climate change.

Scope and preparation of the reports

The IPCC does not carry out research nor does it monitor climate related data. The responsibility of the lead authors of IPCC reports is to assess available information about climate change drawn mainly from the peer reviewed and published scientific/technical literature. The IPCC reports are a compendium of peer reviewed and published science. Each subsequent IPCC report notes areas where the science has improved since the previous report and also notes areas where further research is required.

There are generally three stages in the review process:

- Expert review (6–8 weeks)

- Government/expert review

- Government review of:

- Summaries for Policymakers

- Overview Chapters

- Synthesis Report

Review comments are in an open archive for at least five years.

There are several types of endorsement which documents receive:

- Approval. Material has been subjected to detailed, line by line discussion and agreement.

- Working Group Summaries for Policymakers are approved by their Working Groups.

- Synthesis Report Summary for Policymakers is approved by Panel.

- Adoption. Endorsed section by section (and not line by line).

- Panel adopts Overview Chapters of Methodology Reports.

- Panel adopts IPCC Synthesis Report.

- Acceptance. Not been subject to line by line discussion and agreement, but presents a comprehensive, objective, and balanced view of the subject matter.

- Working Groups accept their reports.

- Task Force Reports are accepted by the Panel.

- Working Group Summaries for Policymakers are accepted by the Panel after group approval.

The Panel is responsible for the IPCC and its endorsement of Reports allows it to ensure they meet IPCC standards.

There have been a range of commentaries on the IPCC's procedures, examples of which are discussed later in the article (see also IPCC Summary for Policymakers). Some of these comments have been supportive, while others have been critical. Some commentators have suggested changes to the IPCC's procedures.

Authors

Each chapter has a number of authors who are responsible for writing and editing the material. A chapter typically has two "coordinating lead authors", ten to fifteen "lead authors", and a somewhat larger number of "contributing authors". The coordinating lead authors are responsible for assembling the contributions of the other authors, ensuring that they meet stylistic and formatting requirements, and reporting to the Working Group chairs. Lead authors are responsible for writing sections of chapters. Contributing authors prepare text, graphs or data for inclusion by the lead authors.

Authors for the IPCC reports are chosen from a list of researchers prepared by governments and participating organisations, and by the Working Group/Task Force Bureaux, as well as other experts known through their published work. The choice of authors aims for a range of views, expertise and geographical representation, ensuring representation of experts from developing and developed countries and countries with economies in transition.

First assessment report

Main article: IPCC First Assessment ReportThe IPCC first assessment report was completed in 1990, and served as the basis of the UNFCCC.

The executive summary of the WG I Summary for Policymakers report says they are certain that emissions resulting from human activities are substantially increasing the atmospheric concentrations of the greenhouse gases, resulting on average in an additional warming of the Earth's surface. They calculate with confidence that CO2 has been responsible for over half the enhanced greenhouse effect. They predict that under a "business as usual" (BAU) scenario, global mean temperature will increase by about 0.3 °C per decade during the century. They judge that global mean surface air temperature has increased by 0.3 to 0.6 °C over the last 100 years, broadly consistent with prediction of climate models, but also of the same magnitude as natural climate variability. The unequivocal detection of the enhanced greenhouse effect is not likely for a decade or more.

Supplementary report of 1992

The 1992 supplementary report was an update, requested in the context of the negotiations on the UNFCCC at the Earth Summit (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992.

The major conclusion was that research since 1990 did "not affect our fundamental understanding of the science of the greenhouse effect and either confirm or do not justify alteration of the major conclusions of the first IPCC scientific assessment". It noted that transient (time-dependent) simulations, which had been very preliminary in the FAR, were now improved, but did not include aerosol or ozone changes.

Second assessment report

Main article: IPCC Second Assessment ReportClimate Change 1995, the IPCC Second Assessment Report (SAR), was finished in 1996. It is split into four parts:

- A synthesis to help interpret UNFCCC article 2.

- The Science of Climate Change (WG I)

- Impacts, Adaptations and Mitigation of Climate Change (WG II)

- Economic and Social Dimensions of Climate Change (WG III)

Each of the last three parts was completed by a separate working group, and each has a Summary for Policymakers (SPM) that represents a consensus of national representatives. The SPM of the WG I report contains headings:

- Greenhouse gas concentrations have continued to increase

- Anthropogenic aerosols tend to produce negative radiative forcings

- Climate has changed over the past century (air temperature has increased by between 0.3 and 0.6 °C since the late 19th century; this estimate has not significantly changed since the 1990 report).

- The balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate (considerable progress since the 1990 report in distinguishing between natural and anthropogenic influences on climate, because of: including aerosols; coupled models; pattern-based studies)

- Climate is expected to continue to change in the future (increasing realism of simulations increases confidence; important uncertainties remain but are taken into account in the range of model projections)

- There are still many uncertainties (estimates of future emissions and biogeochemical cycling; models; instrument data for model testing, assessment of variability, and detection studies)

Chapter 8

Chapter 8 of the Second Assessment Report was subject to the IPCC process of discussion of proposed statements, open review and reconsideration by section lead authors who made changes to the wording in response to comments from governments, individual scientists, and non-governmental organisations. The final version stated that "these results indicate that the observed trend in global mean temperature over the past 100 years is unlikely to be entirely natural in origin. More importantly, there is evidence of an emerging pattern of climate response to forcings by greenhouse gases and sulphate aerosols in the observed climate record. Taken together, these results point towards a human influence on global climate."

A week after the report was released, The Wall Street Journal published a letter from the retired condensed matter physicist and former president of the US National Academy of Sciences, Frederick Seitz, chair of the fossil-fuel industry–funded George C. Marshall Institute and Science and Environmental Policy Project. Seitz had never been a climate scientist, had played no part in the preparation of the IPCC report and had not attended the relevant meetings. In this letter, Seitz denounced the IPCC report, in particular the conclusions of Chapter 8. Seitz wrote "I have never witnessed a more disturbing corruption of the peer-review process than the events that led to this IPCC report".

The position of the lead author of Chapter 8, Benjamin D. Santer, was supported by fellow IPCC authors and senior figures of the American Meteorological Society (AMS) and University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR). The presidents of the AMS and UCAR stated that there was a "systematic effort by some individuals to undermine and discredit the scientific process that has led many scientists working on understanding climate to conclude that there is a very real possibility that humans are modifying Earth's climate on a global scale."

Other rebuttals of Seitz's comments include a 1997 paper by Paul Edwards and IPCC author Stephen Schneider, and a 2007 complaint to the UK broadcast regulator Ofcom about the television programme, "The Great Global Warming Swindle". The 2007 complaint includes a rebuttal of Seitz's claims by the former IPCC chairman, Bert Bolin.

Debate over value of a statistical life

See also: Economics of global warmingOne of the controversies of the Second Assessment Working Group III report is the economic valuation of human life, which is used in monetized (i.e., converted into US dollar values) estimates of climate change impacts. Often in these monetized estimates, the health risks of climate change are valued so that they are "consistent" with valuations of other health risks. There are a wide range of views on monetized estimates of climate change impacts. The strengths and weaknesses of monetized estimates are discussed in the SAR and later IPCC assessments.

In the preparation of the SAR, disagreement arose over the Working Group III Summary for Policymakers (SPM). The SPM is written by a group of IPCC authors, who then discuss the draft with government delegates from all of the UNFCCC Parties (i.e., delegates from most of the world's governments). The economic valuation of human life (referred to by economists as the "value of statistical life") was viewed by some governments (such as India) as suggesting that people living in poor countries are worth less than people living in rich countries. David Pearce, who was a lead author of the relevant chapter of the SAR, officially dissented on the SPM. According to Pearce:

The relevant chapter values of statistical life based on actual studies in different countries What the authors of Chapter 6 did not accept, and still do not accept, was the call from a few delegates for a common valuation based on the highest number for willingness to pay.

In other words, a few government delegates wanted "statistical lives" in poor countries to be valued at the same level as "statistical lives" in rich countries. IPCC author Michael Grubb later commented:

Many of us think that the governments were basically right. The metric makes sense for determining how a given government might make tradeoffs between its own internal projects. But the same logic fails when the issue is one of damage inflicted by some countries on others: why should the deaths inflicted by the big emitters — principally the industrialised countries — be valued differently according to the wealth of the victims' countries?

Third assessment report

Main article: IPCC Third Assessment ReportThe Third Assessment Report (TAR) was completed in 2001 and consists of four reports, three of them from its working groups:

- Working Group I: The Scientific Basis

- Working Group II: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability

- Working Group III: Mitigation

- Synthesis Report

A number of the TAR's conclusions are given quantitative estimates of how probable it is that they are correct, e.g., greater than 66% probability of being correct. These are "Bayesian" probabilities, which are based on an expert assessment of all the available evidence.

"Robust findings" of the TAR Synthesis Report include:

- "Observations show Earth's surface is warming. Globally, 1990s very likely warmest decade in instrumental record". Atmospheric concentrations of anthropogenic (i.e., human-emitted) greenhouse gases have increased substantially.

- Since the mid-20th century, most of the observed warming is "likely" (greater than 66% probability, based on expert judgement) due to human activities.

- Projections based on the Special Report on Emissions Scenarios suggest warming over the 21st century at a more rapid rate than that experienced for at least the last 10,000 years.

- "Projected climate change will have beneficial and adverse effects on both environmental and socio-economic systems, but the larger the changes and the rate of change in climate, the more the adverse effects predominate."

- "Ecosystems and species are vulnerable to climate change and other stresses (as illustrated by observed impacts of recent regional temperature changes) and some will be irreversibly damaged or lost."

- "Greenhouse gas emission reduction (mitigation) actions would lessen the pressures on natural and human systems from climate change."

- "Adaptation has the potential to reduce adverse effects of climate change and can often produce immediate ancillary benefits, but will not prevent all damages." An example of adaptation to climate change is building levees in response to sea level rise.

Comments on the TAR

In 2001, 17 national science academies issued a joint-statement on climate change, in which they stated "we support the conclusion that it is at least 90% certain that temperatures will continue to rise, with average global surface temperature projected to increase by between 1.4 and 5.8 °C above 1990 levels by 2100." The TAR has also been endorsed by the Canadian Foundation for Climate and Atmospheric Sciences, Canadian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society, and European Geosciences Union (refer to "Endorsements of the IPCC").

In 2001, the US National Research Council (US NRC) produced a report that assessed Working Group I's (WGI) contribution to the TAR. US NRC (2001) "generally agrees" with the WGI assessment, and describes the full WGI report as an "admirable summary of research activities in climate science".

IPCC author Richard Lindzen has made a number of criticisms of the TAR. Among his criticisms, Lindzen has stated that the WGI Summary for Policymakers (SPM) does not faithfully summarize the full WGI report. For example, Lindzen states that the SPM understates the uncertainty associated with climate models. John Houghton, who was a co-chair of TAR WGI, has responded to Lindzen's criticisms of the SPM. Houghton has stressed that the SPM is agreed upon by delegates from many of the world's governments, and that any changes to the SPM must be supported by scientific evidence.

IPCC author Kevin Trenberth has also commented on the WGI SPM. Trenberth has stated that during the drafting of the WGI SPM, some government delegations attempted to "blunt, and perhaps obfuscate, the messages in the report". However, Trenberth concludes that the SPM is a "reasonably balanced summary."

US NRC (2001) concluded that the WGI SPM and Technical Summary are "consistent" with the full WGI report. US NRC (2001) stated:

the full report is adequately summarized in the Technical Summary. The full WGI report and its Technical Summary are not specifically directed at policy. The Summary for Policymakers reflects less emphasis on communicating the basis for uncertainty and a stronger emphasis on areas of major concern associated with human-induced climate change. This change in emphasis appears to be the result of a summary process in which scientists work with policy makers on the document. Written responses from U.S. coordinating and lead scientific authors to the committee indicate, however, that (a) no changes were made without the consent of the convening lead authors (this group represents a fraction of the lead and contributing authors) and (b) most changes that did occur lacked significant impact.

Fourth assessment report

Main article: IPCC Fourth Assessment ReportThe Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) was published in 2007. Like previous assessment reports, it consists of four reports:

- Working Group I: The Physical Science Basis

- Working Group II: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability

- Working Group III: Mitigation

- Synthesis Report

People from over 130 countries contributed to the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, which took 6 years to produce. Contributors to AR4 included more than 2500 scientific expert reviewers, more than 800 contributing authors, and more than 450 lead authors.

"Robust findings" of the Synthesis report include:

- "Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, as is now evident from observations of increases in global average air and ocean temperatures, widespread melting of snow and ice and rising global average sea level."

- Most of the global average warming over the past 50 years is "very likely" (greater than 90% probability, based on expert judgement) due to human activities.

- "Impacts will very likely increase due to increased frequencies and intensities of some extreme weather events."

- "Anthropogenic warming and sea level rise would continue for centuries even if GHG emissions were to be reduced sufficiently for GHG concentrations to stabilise, due to the time scales associated with climate processes and feedbacks." Stabilization of atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations is discussed in climate change mitigation.

- "Some planned adaptation (of human activities) is occurring now; more extensive adaptation is required to reduce vulnerability to climate change."

- "Unmitigated climate change would, in the long term, be likely to exceed the capacity of natural, managed and human systems to adapt"

- "Many impacts can be reduced, delayed or avoided by mitigation."

Global warming projections from AR4 are shown below. The projections apply to the end of the 21st century (2090–99), relative to temperatures at the end of the 20th century (1980–99). Add 0.7 °C to projections to make them relative to pre-industrial levels instead of 1980–99. Descriptions of the greenhouse gas emissions scenarios can be found in Special Report on Emissions Scenarios.

| Emissions scenario |

Best estimate (°C) |

"Likely" range (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| B1 | 1.8 | 1.1 – 2.9 |

| A1T | 2.4 | 1.4 – 3.8 |

| B2 | 2.4 | 1.4 – 3.8 |

| A1B | 2.8 | 1.7 – 4.4 |

| A2 | 3.4 | 2.0 – 5.4 |

| A1FI | 4.0 | 2.4 – 6.4 |

"Likely" means greater than 66% probability of being correct, based on expert judgement.

Response to AR4

Several science academies have referred to and/or reiterated some of the conclusions of AR4. These include:

- Joint-statements made in 2007, 2008 and 2009 by the science academies of Brazil, China, India, Mexico, South Africa and the G8 nations (the "G8+5").

- Publications by the Australian Academy of Science.

- A joint-statement made in 2007 by the Network of African Science Academies.

- A statement made in 2010 by the Inter Academy Medical Panel This statement has been signed by 43 scientific academies.

This conclusion is based on a substantial array of scientific evidence, including recent work, and is consistent with the conclusions of recent assessments by the U.S. Global Change Research Program , the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Fourth Assessment Report , and other assessments of the state of scientific knowledge on climate change.Climate change is occurring, is caused largely by human activities, and poses significant risks for—and in many cases is already affecting—a broad range of human and natural systems .

Some errors have been found in the IPCC AR4 Working Group II report. Two errors include the melting of Himalayan glaciers (see later section), and Dutch land area that is below sea level.

Fifth assessment report

Main article: IPCC Fifth Assessment ReportThe IPCC is currently starting to outline its Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) which will be finalized in 2014. Working Group I (Stockholm, Sweden) is published in September 2013. The report increases the degree of certainty that human activities are driving the warming the world has experienced, from "very likely" or 90% confidence in 2007, to "extremely likely" or 95% confidence now.

As it has been the case in the past, the outline of the AR5 will be developed through a scoping process which involves climate change experts from all relevant disciplines and users of IPCC reports, in particular representatives from governments. As a first step, experts, governments and organizations involved in the Fourth Assessment Report have been asked to submit comments and observations in writing. These submissions are currently being analysed by members of the Bureau. The scoping meeting of experts to define the outline of the AR5 took place on 13–17 July 2009. The outline was submitted to the 31st Session of the IPCC held in Bali, Indonesia, 26–29 October 2009.

Special reports

In addition to climate assessment reports, the IPCC is publishing Special Reports on specific topics. The preparation and approval process for all IPCC Special Reports follows the same procedures as for IPCC Assessment Reports. In the year 2011 two IPCC Special Report were finalized, the Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation (SRREN) and the Special Report on Managing Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation (SREX). Both Special Reports were requested by governments.

Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES)

The Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES) is a report by the IPCC which was published in 2000. The SRES contains "scenarios" of future changes in emissions of greenhouse gases and sulfur dioxide. One of the uses of the SRES scenarios is to project future changes in climate, e.g., changes in global mean temperature. The SRES scenarios were used in the IPCC's Third and Fourth Assessment Reports.

The SRES scenarios are "baseline" (or "reference") scenarios, which means that they do not take into account any current or future measures to limit greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (e.g., the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change). SRES emissions projections are broadly comparable in range to the baseline projections that have been developed by the scientific community.

Comments on the SRES

There have been a number of comments on the SRES. Parson et al. (2007) stated that the SRES represented "a substantial advance from prior scenarios". At the same time, there have been criticisms of the SRES.

The most prominently publicized criticism of SRES focused on the fact that all but one of the participating models compared gross domestic product (GDP) across regions using market exchange rates (MER), instead of the more correct purchasing-power parity (PPP) approach. This criticism is discussed in the main SRES article.

Special report on renewable energy sources and climate change mitigation (SRREN)

This report assesses existing literature on renewable energy commercialisation for the mitigation of climate change. It covers the six most important renewable energy technologies, as well as their integration into present and future energy systems. It also takes into consideration the environmental and social consequences associated with these technologies, the cost and strategies to overcome technical as well as non-technical obstacles to their application and diffusion.

More than 130 authors from all over the world contributed to the preparation of IPCC Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation (SRREN) on a voluntary basis – not to mention more than 100 scientists, who served as contributing authors.

Special Report on managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation (SREX)

The report assesses the effect that climate change has on the threat of natural disasters and how nations can better manage an expected change in the frequency of occurrence and intensity of severe weather patterns. It aims to become a resource for decision-makers to prepare more effectively for managing the risks of these events. A potentially important area for consideration is also the detection of trends in extreme events and the attribution of these trends to human influence.

More than 80 authors, 19 review editors, and more than 100 contributing authors from all over the world contributed to the preparation of SREX.

Methodology reports

Within IPCC the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Program develops methodologies to estimate emissions of greenhouse gases. This has been undertaken since 1991 by the IPCC WGI in close collaboration with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the International Energy Agency. The objectives of the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Program are:

- to develop and refine an internationally agreed methodology and software for the calculation and reporting of national greenhouse gas emissions and removals; and

- to encourage the widespread use of this methodology by countries participating in the IPCC and by signatories of the UNFCCC.

Revised 1996 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories

The 1996 Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Investories provide the methodological basis for the estimation of national greenhouse gas emissions inventories. Over time these guidelines have been completed with good practice reports: Good Practice Guidance and Uncertainty Management in National Greenhouse Gas Inventories and Good Practice Guidance for Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry.

The 1996 guidelines and the two good practice reports are to be used by parties to the UNFCCC and to the Kyoto Protocol in their annual submissions of national greenhouse gas inventories.

2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories

The 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories is the latest version of these emission estimation methodologies, including a large number of default emission factors. Although the IPCC prepared this new version of the guidelines on request of the parties to the UNFCCC, the methods have not yet been officially accepted for use in national greenhouse gas emissions reporting under the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol.

Activities

The IPCC concentrates its activities on the tasks allotted to it by the relevant WMO Executive Council and UNEP Governing Council resolutions and decisions as well as on actions in support of the UNFCCC process.

In April 2006, the IPCC released the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report or AR4. Reports of the workshops held so far are available at the IPCC website.

- Working Group I:

- Report was due to be finalized during February 2007 and was finished on schedule.

- By May 2005, there had been 3 AR4 meetings, with only public information being meeting locations, an author list, one invitation, one agenda, and one list of presentation titles.

- By December 2006, governments were reviewing the revised summary for policy makers.

- Working Group II:

- Report was due to be finalized in mid-2007 and was completed on schedule.

- In May 2005, there had been 2 AR4 meetings, with no public information released.

- One shared meeting with WG III had taken place, with a published summary.

- Working Group III:

- Report was due to be finalized in mid-2007.

- In May 2005, there had been 1 AR4 meeting, with no public information released.

The AR4 Synthesis Report (SYR) was finalized in November 2007. Documentation on the scoping meetings for the AR4 are available as are the outlines for the WG I report Template:PDFlink and a provisional author list Template:PDFlink.

While the preparation of the assessment reports is a major IPCC function, it also supports other activities, such as the Data Distribution Centre and the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme, required under the UNFCCC. This involves publishing default emission factors, which are factors used to derive emissions estimates based on the levels of fuel consumption, industrial production and so on.

The IPCC also often answers inquiries from the UNFCCC Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA).

Nobel Peace Prize

Main article: 2007 Nobel Peace PrizeIn December 2007, the IPCC was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize "for their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change". The award is shared with Former U.S. Vice-President Al Gore for his work on climate change and the documentary An Inconvenient Truth.

Responses and criticisms

Various criticisms have been raised, both about the specific content of IPCC reports, as well as about the process undertaken to produce the reports. Most scientific experts consider that the content issues are relatively minor. On 13 March 2010, an open letter, signed by over 250 scientists in the United States, was sent to U.S. federal agencies that "None of the handful of mis-statements (out of hundreds and hundreds of unchallenged statements) remotely undermines the conclusion that 'warming of the climate system is unequivocal' and that most of the observed increase in global average temperatures since the mid-twentieth century is very likely due to observed increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations".

In response to criticisms in 2010, the InterAcademy Council to produced an independent investigation into the IPCC, which took evidence both from experts and from the general public. The investigation noted the increasing complexity and intensity of public debate, and recommended reforms to the IPCC management structure to strengthen ongoing decision-making, maintaining transparency and coverage of the full range of scientific views, together with procedural improvements to further minimise errors.

Projected date of melting of Himalayan glaciers

Main article: Criticism of the IPCC AR4A paragraph in the 2007 Working Group II report ("Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability"), chapter 10 included a projection that Himalayan glaciers could disappear by 2035

- Glaciers in the Himalaya are receding faster than in any other part of the world (see Table 10.9) and, if the present rate continues, the likelihood of them disappearing by the year 2035 and perhaps sooner is very high if the Earth keeps warming at the current rate. Its total area will likely shrink from the present 500,000 to 100,000 km by the year 2035 (WWF, 2005).

This projection was not included in the final summary for policymakers. The IPCC has since acknowledged that the date is incorrect, while reaffirming that the conclusion in the final summary was robust. They expressed regret for "the poor application of well-established IPCC procedures in this instance". The date of 2035 has been correctly quoted by the IPCC from the WWF report, which has misquoted its own source, an ICSI report "Variations of Snow and Ice in the past and at present on a Global and Regional Scale".

Rajendra K. Pachauri responded in an interview with Science.

Watson criticism

Former IPCC chairman Robert Watson has said "The mistakes all appear to have gone in the direction of making it seem like climate change is more serious by overstating the impact. That is worrying. The IPCC needs to look at this trend in the errors and ask why it happened". Martin Parry, a climate expert who had been co-chair of the IPCC working group II, said that "What began with a single unfortunate error over Himalayan glaciers has become a clamour without substance" and the IPCC had investigated the other alleged mistakes, which were "generally unfounded and also marginal to the assessment".

Emphasis of the "hockey stick" graph

Main articles: Hockey stick graph and Hockey stick controversy

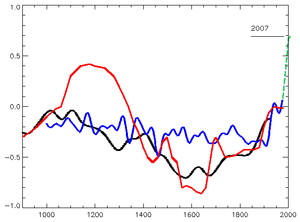

The third assessment report (TAR) prominently featured a graph labeled "Millennial Northern Hemisphere temperature reconstruction" based on a 1999 paper by Michael E. Mann, Raymond S. Bradley and Malcolm K. Hughes (MBH99), which has been referred to as the "hockey stick graph". This graph extended the similar graph in Figure 3.20 from the IPCC Second Assessment Report of 1995, and differed from a schematic in the first assessment report that lacked temperature units, but appeared to depict larger global temperature variations over the past 1000 years, and higher temperatures during the Medieval Warm Period than the mid 20th century. The schematic was not an actual plot of data, and was based on a diagram of temperatures in central England, with temperatures increased on the basis of documentary evidence of Medieval vineyards in England. Even with this increase, the maximum it showed for the Medieval Warm Period did not reach temperatures recorded in central England in 2007. The MBH99 finding was supported by cited reconstructions by Jones et al. 1998 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFJonesBriffaBarnettTett1998 (help), Pollack, Huang & Shen 1998 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPollackHuangShen1998 (help), Crowley & Lowery 2000 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCrowleyLowery2000 (help) and Briffa 2000 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBriffa2000 (help), using differing data and methods. The Jones et al. and Briffa reconstructions were overlaid with the MBH99 reconstruction in Figure 2.21 of the IPCC report.

These studies were widely presented as demonstrating that the current warming period is exceptional in comparison to temperatures between 1000 and 1900, and the MBH99 based graph featured in publicity. Even at the draft stage, this finding was disputed by contrarians: in May 2000 Fred Singer's Science and Environmental Policy Project held a press event on Capitol Hill, Washington, D.C., featuring comments on the graph Wibjörn Karlén and Singer argued against the graph at a United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation hearing on 18 July 2000. Contrarian John Lawrence Daly featured a modified version of the IPCC 1990 schematic, which he mis-identified as appearing in the IPCC 1995 report, and argued that "Overturning its own previous view in the 1995 report, the IPCC presented the 'Hockey Stick' as the new orthodoxy with hardly an apology or explanation for the abrupt U-turn since its 1995 report." Criticism of the MBH99 reconstruction in a review paper, which was quickly discredited in the Soon and Baliunas controversy, was picked up by the Bush administration, and a Senate speech by US Republican senator James Inhofe alleged that "manmade global warming is the greatest hoax ever perpetrated on the American people". The data and methodology used to produce the "hockey stick graph" was criticized in papers by Stephen McIntyre and Ross McKitrick, and in turn the criticisms in these papers were examined by other studies and comprehensively refuted by Wahl & Ammann 2007 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWahlAmmann2007 (help), which showed errors in the methods used by McIntyre and McKitrick.

On 23 June 2005, Rep. Joe Barton, chairman of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce wrote joint letters with Ed Whitfield, Chairman of the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations demanding full records on climate research, as well as personal information about their finances and careers, from Mann, Bradley and Hughes. Sherwood Boehlert, chairman of the House Science Committee, said this was a "misguided and illegitimate investigation" apparently aimed at intimidating scientists, and at his request the U.S. National Academy of Sciences arranged for its National Research Council to set up a special investigation. The National Research Council's report agreed that there were some statistical failings, but these had little effect on the graph, which was generally correct. In a 2006 letter to Nature, Mann, Bradley, and Hughes pointed out that their original article had said that "more widespread high-resolution data are needed before more confident conclusions can be reached" and that the uncertainties were "the point of the article."

The IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) published in 2007 featured a graph showing 12 proxy based temperature reconstructions, including the three highlighted in the 2001 Third Assessment Report (TAR); Mann, Bradley & Hughes 1999 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMannBradleyHughes1999 (help) as before, Jones et al. 1998 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFJonesBriffaBarnettTett1998 (help) and Briffa 2000 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBriffa2000 (help) had both been calibrated by newer studies. In addition, analysis of the Medieval Warm Period cited reconstructions by Crowley & Lowery 2000 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCrowleyLowery2000 (help) (as cited in the TAR) and Osborn & Briffa 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFOsbornBriffa2006 (help). Ten of these 14 reconstructions covered 1,000 years or longer. Most reconstructions shared some data series, particularly tree ring data, but newer reconstructions used additional data and covered a wider area, using a variety of statistical methods. The section discussed the divergence problem affecting certain tree ring data.

Conservative nature of IPCC reports

Some critics have contended that the IPCC reports tend to underestimate dangers, understate risks, and report only the "lowest common denominator" findings.

On 1 February 2007, the eve of the publication of IPCC's major report on climate, a study was published suggesting that temperatures and sea levels have been rising at or above the maximum rates proposed during the last IPCC report in 2001. The study compared IPCC 2001 projections on temperature and sea level change with observations. Over the six years studied, the actual temperature rise was near the top end of the range given by IPCC's 2001 projection, and the actual sea level rise was above the top of the range of the IPCC projection.

Another example of scientific research which suggests that previous estimates by the IPCC, far from overstating dangers and risks, have actually understated them is a study on projected rises in sea levels. When the researchers' analysis was "applied to the possible scenarios outlined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the researchers found that in 2100 sea levels would be 0.5–1.4 m above 1990 levels. These values are much greater than the 9–88 cm as projected by the IPCC itself in its Third Assessment Report, published in 2001". This may have been due, in part, to the expanding human understanding of climate.

In reporting criticism by some scientists that IPCC's then-impending January 2007 report understates certain risks, particularly sea level rises, an AP story quoted Stefan Rahmstorf, professor of physics and oceanography at Potsdam University as saying "In a way, it is one of the strengths of the IPCC to be very conservative and cautious and not overstate any climate change risk".

In his December 2006 book, Hell and High Water: Global Warming, and in an interview on Fox News on 31 January 2007, energy expert Joseph Romm noted that the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report is already out of date and omits recent observations and factors contributing to global warming, such as the release of greenhouse gases from thawing tundra.

Political influence on the IPCC has been documented by the release of a memo by ExxonMobil to the Bush administration, and its effects on the IPCC's leadership. The memo led to strong Bush administration lobbying, evidently at the behest of ExxonMobil, to oust Robert Watson, a climate scientist, from the IPCC chairmanship, and to have him replaced by Pachauri, who was seen at the time as more mild-mannered and industry-friendly.

IPCC processes

In 2005, the UK House of Lords Select Committee on Economic Affairs (of which Nigel Lawson, the noted climate sceptic, was a member) produced a report on the economics of climate change. It commented on the IPCC process:

We have some concerns about the objectivity of the IPCC process, with some of its emissions scenarios and summary documentation apparently influenced by political considerations. There are significant doubts about some aspects of the IPCC's emissions scenario exercise, in particular, the high emissions scenarios. The Government should press the IPCC to change their approach. There are some positive aspects to global warming and these appear to have been played down in the IPCC reports; the Government should press the IPCC to reflect in a more balanced way the costs and benefits of climate change. The Government should press the IPCC for better estimates of the monetary costs of global warming damage and for explicit monetary comparisons between the costs of measures to control warming and their benefits. Since warming will continue, regardless of action now, due to the lengthy time lags.

— The Economics of Climate ChangePDF

The Stern Review ordered by the UK government, whose findings were released in October 2006, made a stronger argument in favor of urgent action to combat human-made climate change than previous analyses, including some by IPCC. The conclusions of the Stern Review have been contested, however.

The structural elements of the IPCC processes have been criticized in other ways, with the design of the processes during the formation of the IPCC making its reports prone not to exaggerations, but to underestimating dangers, under-stating risks, and reporting only the "least common denominator" findings which by design make it through the bureaucracy. As noted by Spencer Weart, Director of the Center for History of Physics at the American Institute of Physics,

The Reagan administration wanted to forestall pronouncements by self-appointed committees of scientists, fearing they would be 'alarmist.' Conservatives promoted the IPCC's clumsy structure, which consisted of representatives appointed by every government in the world and required to consult all the thousands of experts in repeated rounds of report-drafting in order to reach a consensus. Despite these impediments the IPCC has issued unequivocal statements on the urgent need to act.

Climatologist Judith Curry, who supports the scientific conclusions of the IPCC reports generally, has publicly criticized aspects of the IPCC's process, expressions of certainty, and treatment of dissent.

Outdatedness of reports

Since the IPCC does not carry out its own research, it operates on the basis of scientific papers and independently documented results from other scientific bodies, and its schedule for producing reports requires a deadline for submissions prior to the report's final release. In principle, this means that any significant new evidence or events that change our understanding of climate science between this deadline and publication of an IPCC report cannot be included. In an area of science where our scientific understanding is rapidly changing, this has been raised as a serious shortcoming in a body which is widely regarded as the ultimate authority on the science. However, there has generally been a steady evolution of key findings and levels of scientific confidence from one assessment report to the next.

The submission deadlines for the Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) differed for the reports of each Working Group. Deadlines for the Working Group I report were adjusted during the drafting and review process in order to ensure that reviewers had access to unpublished material being cited by the authors. The final deadline for cited publications was 24 July 2006. The final WG I report was released on 30 April 2007 and the final AR4 Synthesis Report was released on 17 November 2007.

Rajendra Pachauri, the IPCC chair, admitted at the launch of this report that since the IPCC began work on it, scientists have recorded "much stronger trends in climate change", like the unforeseen dramatic melting of polar ice in the summer of 2007, and added, "that means you better start with intervention much earlier".

Burden on participating scientists

Scientists who participate in the IPCC assessment process do so without any compensation other than the normal salaries they receive from their home institutions. The process is labor intensive, diverting time and resources from participating scientists' research programs. Concerns have been raised that the large uncompensated time commitment and disruption to their own research may discourage qualified scientists from participating.

In May 2010, Pachauri noted that the IPCC currently had no process for responding to errors or flaws once it issued a report. The problem, according to Pachauri, was that once a report was issued the panels of scientists producing the reports were disbanded.

Proposed organizational overhaul

In February 2010, in response to controversies regarding claims in the Fourth Assessment Report, five climate scientists – all contributing or lead IPCC report authors – wrote in the journal Nature calling for changes to the IPCC. They suggested a range of new organizational options, from tightening the selection of lead authors and contributors, to dumping it in favor of a small permanent body, or even turning the whole climate science assessment process into a moderated "living" Misplaced Pages-IPCC. Other recommendations included that the panel employ a full-time staff and remove government oversight from its processes to avoid political interference.

In response to criticisms in 2010, the U.N. requested the InterAcademy Council to produce an independent investigation into the IPCC. The investigating committee took evidence both from experts and from the general public, who were invited to contribute views. The committee's report found that the response to discovery of errors had been slow and inadequate, and recommended changes to the management structure to provide year-round decision-making and responsiveness, as well as including members outside the IPCC process to increase independence. A conflict of interest policy was to be developed and implemented, guidelines for use on non peer-reviewed material were to be made more specific, and characterization of uncertainty was to be made more consistent. The review process was to be streamlined to reduce the burden on lead authors, who were to ensure that all reasonable viewpoints were given consideration, while using professional judgment to assess whether alternative views should be included or given equal weight.

InterAcademy Council review

In March 2010, at the invitation of the United Nations secretary-general and the chair of the IPCC, the InterAcademy Council (IAC) was asked to review the IPCC's processes for developing its reports. The IAC panel, chaired by Harold Tafler Shapiro, convened on 14 May 2010 and released its report on 1 September 2010.

The IAC found that, "The IPCC assessment process has been successful overall". The panel, however, made seven formal recommendations for improving the IPCC's assessment process, including:

- establish an executive committee;

- elect an executive director whose term would only last for one assessment;

- encourage review editors to ensure that all reviewer comments are adequately considered and genuine controversies are adequately reflected in the assessment reports;

- adopt a better process for responding to reviewer comments;

- working groups should use a qualitative level-of-understanding scale in the Summary for Policy Makers and Technical Summary;

- "Quantitative probabilities (as in the likelihood scale) should be used to describe the probability of well-defined outcomes only when there is sufficient evidence"; and

- implement a communications plan that emphasizes transparency and establish guidelines for who can speak on behalf of the organization.

The panel also advised that the IPCC avoid appearing to advocate specific policies in response to its scientific conclusions. Commenting on the IAC report, Nature News noted that "The proposals were met with a largely favourable response from climate researchers who are eager to move on after the media scandals and credibility challenges that have rocked the United Nations body during the past nine months".

Endorsements of the IPCC

Various scientific bodies have issued official statements endorsing and concurring with the findings of the IPCC.

- Joint science academies' statement of 2001. "The work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) represents the consensus of the international scientific community on climate change science. We recognise IPCC as the world's most reliable source of information on climate change and its causes, and we endorse its method of achieving this consensus".

- Canadian Foundation for Climate and Atmospheric Sciences. "We concur with the climate science assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2001 ... We endorse the conclusions of the IPCC assessment..."

- Canadian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society. "CMOS endorses the process of periodic climate science assessment carried out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and supports the conclusion, in its Third Assessment Report, which states that the balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate."

- European Geosciences Union. "The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is the main representative of the global scientific community IPCC third assessment report represents the state-of-the-art of climate science supported by the major science academies around the world and by the vast majority of scientific researchers and investigations as documented by the peer-reviewed scientific literature".

- International Council for Science. "...the IPCC 4th Assessment Report represents the most comprehensive international scientific assessment ever conducted. This assessment reflects the current collective knowledge on the climate system, its evolution to date, and its anticipated future development".

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (USA). "Internationally, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)... is the most senior and authoritative body providing scientific advice to global policy makers".

- United States National Research Council. "The conclusion that most of the observed warming of the last 50 years is likely to have been due to the increase in greenhouse gas concentrations accurately reflects the current thinking of the scientific community on this issue".

- Network of African Science Academies. "The IPCC should be congratulated for the contribution it has made to public understanding of the nexus that exists between energy, climate and sustainability".

- Royal Meteorological Society, in response to the release of the Fourth Assessment Report, referred to the IPCC as "The world's best climate scientists".

- Stratigraphy Commission of the Geological Society of London. "The most authoritative assessment of climate change in the near future is provided by the Inter-Governmental Panel for Climate Change".

See also

- Avoiding dangerous climate change

- CLOUD

- G8+5, a group of leaders consisting of the heads of government from the G8 nations

- Indian Network on Climate Change Assessment

- List of authors from Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis

- List of scientists opposing the mainstream scientific assessment of global warming

- Post–Kyoto Protocol negotiations on greenhouse gas emissions

- Robust decision making

- Scientific opinion on climate change

Notes

- "Organization". Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- "A guide to facts and fictions about climate change" (PDF). The Royal Society. March 2005. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- ^ Weart, Spencer (December 2011). "International Cooperation: Democracy and Policy Advice (1980s)". The Discovery of Global Warming. American Institute of Physics. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ "Principles governing IPCC work" (PDF). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 28 April 2006.

- "Understanding Climate Change: 22 years of IPCC assessment" (PDF). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). November 2010. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- "About IPCC – Mandate and Membership of the IPCC". Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2007. Archived from the original on 20 January 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2007.web archive

- "A guide to facts and fiction about climate change". The Royal Society. March 2005. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- Sample, Ian (2 February 2007). "Scientists offered cash to dispute climate study". London: Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

Lord Rees of Ludlow, the president of the Royal Society, Britain's most prestigious scientific institute, said: "The IPCC is the world's leading authority on climate change..."

- "The Nobel Peace Prize for 2007". Nobelprize.org. 12 October 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- IPCC. Template:PDFlink. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- IPCC. Official documents. Retrieved December 2006. web archive, 21 February 2010

- IPCC. Template:PDFlink. 19 February 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2006. Web archive pdf file damaged 20`0-02-21

- ^ IPCC. Template:PDFlink. 19 February 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2006.

- IPCC. Mandate and Membership of IPCC. Retrieved 20 December 2006. Web archive 21 February 2010

- "Appendix A to the Principles Governing IPCC Work" (PDF). April 1999.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|firmat=ignored (help) - e.g., Barker, T. (28 February 2005). "House of Lords Select Committee on Economic Affairs Minutes of Evidence. Memorandum by Dr Terry Baker, Cambridge University"Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link), in Economic Affairs Committee 2005 - e.g., Economic Affairs Committee. "Abstract"Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link), in Economic Affairs Committee 2005 - e.g., Interacademy Council (1 October 2010). "Executive summary". Climate Change Assessments, Review of the Processes & Procedures of the IPCC. ISBN 978-90-6984-617-0Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). Report website. - ^

"Ch. 2: Complete Transcript and Rebuttal". Sec. 2.12: Conspiracy Theory About the IPCC.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Missing or empty|title=(help), in Rive et al. 2007, pp. 94–95 - IPCC Second Assessment Report: Climate Change 1995. ch 8, summary, p 412

- Seitz, F. (12 June 1996). Major deception on global warming. Wall Street Journal. p. A16.

- Lahsen, M. (1999). The Detection and Attribution of Conspiracies: The Controversy Over Chapter 8. In G. E. Marcus (Ed.), Paranoia Within Reason: A Casebook on Conspiracy as Explanation (pp. 111–136). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-50458-1.

- ^ Rasmussen, C. (ed) (25 July 1996). "Special insert—An open letter to Ben Santer". UCAR Quarterly. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Edwards, P. and S. Schneider (1997). "The 1995 IPCC Report: Broad Consensus or "Scientific Cleansing"?" (PDF). Ecofable/Ecoscience, 1:1 (1997), pp. 3–9. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) -

"Appendix G: Professor Bert Bolin's Peer Review Comments". Comment 9 (Comment 114 in the current document).

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Missing or empty|title=(help), in Rive et al. 2007, pp. 165–166 - The has been documented in a number of sources:

- F. Pearce (19 August 1995). "Global Row over Value of Human Life". New Scientist: 7.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - E. Masood (1995). "Developing Countries Dispute Use of Figures on Climate Change Impact". Nature. 376 (6539): 374. Bibcode:1995Natur.376R.374M. doi:10.1038/376374b0.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - E. Masood and A. Ochert (1995). "UN Climate Change Report Turns up the Heat". Nature. 378 (6553): 119. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..119M. doi:10.1038/378119a0.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - A. Meyer (1995). "Economics of Climate Change". Nature. 378 (6556): 433. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..433M. doi:10.1038/378433a0.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - N. Sundaraman (1995). "Impact of Climate Change". Nature. 377 (6549): 472. Bibcode:1995Natur.377..472H. doi:10.1038/377472c0. PMID 7566134.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - T. O'Riordan (1997). "Review of Climate Change 1995 – Economic and Social Dimension". Environment. 39 (9): 34–39. doi:10.1080/00139159709604768.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- F. Pearce (19 August 1995). "Global Row over Value of Human Life". New Scientist: 7.

- ^

Pearce, D.W.; et al. "Ch. 6: The social costs of climate change: greenhouse damage and the benefits of control. Box 6.1 Attributing a monetary value to a statistical life"Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link), in IPCC SAR WG3 1996, p. 196 (p.194 of PDF) -

Ackerman, F. (18 May 2004). "Priceless Benefits, Costly Mistakes: What's Wrong With Cost-Benefit Analysis?". Post-autistic economics review. pp. 2–7Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) -

For example:

- Nordhaus, W.D. (2008). "Summary for the Concerned Citizen". A Question of Balance: Weighing the Options on Global Warming Policies (PDF). New Haven, Connecticut, USA: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13748-4Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link), pp.4–19 - Spash, C.L. (10 February 2007). "Climate change: Need for new economic thought" (PDF). Economic and Political WeeklyTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link), pp.485–486. - "Ch 6: Economic modelling of climate-change impacts. Sec 6.1: Introduction" (PDF)Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link), in Stern 2006, pp. 144–145 - "Ch 2: Economics, Ethics and Climate Change. Sec 2.3: Ethics, welfare and economic policy" (PDF)Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link), in Stern 2006, pp. 28–31 - Sussman, F.G.; et al. (2008). "Ch. 4: Effects of Global Change on Human Welfare: Sec 4.3 An economic approach to human welfare". Analyses of the effects of global change on human health and welfare and human systems. A Report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. pp. 124–128Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link)

- Nordhaus, W.D. (2008). "Summary for the Concerned Citizen". A Question of Balance: Weighing the Options on Global Warming Policies (PDF). New Haven, Connecticut, USA: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13748-4Template:Inconsistent citations

- Chapter 5 of the SAR Working Group III report (IPCC SAR WG3 1996) discusses how cost-benefit analysis (which extensively uses monetized estimates) can be applied to climate change. Other chapters (1–4, 6, and 10) also contain relevant information.

- For example:

- Ahmad, Q.K.; et al. "Ch 2. Methods and tools". Sec 2.5. Methods for Costing and ValuationTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link), in IPCC TAR WG2 2001, pp. 120–126. - Fisher, B.S.; et al. "Ch 3: Issues related to mitigation in the long-term context". Sec 3.5.3.3 Cost-benefit analysis, damage cost estimates and social costs of carbonTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link), in IPCC AR4 WG3 2007

- Ahmad, Q.K.; et al. "Ch 2. Methods and tools". Sec 2.5. Methods for Costing and ValuationTemplate:Inconsistent citations

- ^ Grubb, M. (September 2005). "Stick to the Target" (PDF). Prospect Magazine.

-

Committee on the Science of Climate Change, US National Research Council (2001). "Ch. 7: Assessing Progress in Climate Science". Climate Change Science: An Analysis of Some Key Questions. Washington, D.C., USA: National Academy Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-309-07574-2. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Pearce, D. (1 January 1996). "Correction on Global Warming Cost Benefit Conflict". Environmental Damage Valuation and Cost Benefit News. Archived from the original on 16 July 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge. "Michael Grubb: Other positions and activities". University of Cambridge Faculty of Economics website. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- Working Group 1, IPCC.

- Working Group 2, IPCC.

- Working Group 3, IPCC.

- Synthesis Report, IPCC.

- ^

"Question 2", Box 2-1

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC TAR SYR 2001, p. 44 -

Ahmad, Q.K.; et al., "Ch 2: Methods and Tools", Sec. 2.6.2. "Objective" and "Subjective" Probabilities are not Always Explicitly Distinguished

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC TAR WG2 2001. -

Granger Morgan, M.; et al. (2009), Synthesis and Assessment Product 5.2: Best practice approaches for characterizing, communicating, and incorporating scientific uncertainty in decisionmaking. A Report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program (CCSP) and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research (PDF), Washington D.C., USA.: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help), pp.19–20; 27–28. Report website. - ^

"Summary for Policymakers", Table SPM-3, Question 9

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC TAR SYR 2001. -

Nicholls, R.J.; et al., "Ch 6: Coastal Systems and Low-Lying Areas", Table 6.11

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG2 2007, p. 343 - ^

The joint-statement was made by the Australian Academy of Science, the Royal Flemish Academy of Belgium for Science and the Arts, the Brazilian Academy of Sciences, the Royal Society of Canada, the Caribbean Academy of Sciences, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the French Academy of Sciences, the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina, the Indian National Science Academy, the Indonesian Academy of Sciences, the Royal Irish Academy, Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei (Italy), the Academy of Sciences Malaysia, the Academy Council of the Royal Society of New Zealand, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and the Royal Society (UK). Joint statement by 17 national science academies (17 May 2001), The Science of Climate Change (PDF), London, UK: Royal Society, ISBN 0854035583

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link). Statement website at the UK Royal Society. Also published as: "The Science of Climate Change (editorial)", Science, 292 (5520): 1261, 18 May 2001, doi:10.1126/science.292.5520.1261 - ^ CFCAS Letter to PM, November 25, 2005

- ^ Bob Jones. "CMOS Position Statement on Global Warming". Cmos.ca. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ European Geosciences Union Divisions of Atmospheric and Climate Sciences (7 July 2005). "Position Statement on Climate Change and Recent Letters from the Chairman of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce".

- US NRC 2001

-

"Summary",

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in US NRC 2001, p. 1 - ^ "Summary",

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in US NRC 2001, p. 4 - ^ Lindzen, R.S. (1 May 2001), PREPARED STATEMENT OF DR. RICHARD S. LINDZEN, MASSACHUSSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, in: S. Hrg. 107-1027 – INTERGOVERNMENTAL PANEL ON CLIMATE CHANGE (IPCC) THIRD ASSESSMENT REPORT. US Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office (GPO), pp.29–31. Available in text and PDF formats. Also available as a PDF from Professor Lindzen's website.

-

Preface

{{citation}}: External link in|title= - ^ The Great Global Warming Swindle. Programme directed by Martin Durkin, on Channel 4 on Thursday 8 March 2007. Critique by John Houghton, President, John Ray Initiative (PDF), Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, UK: John Ray Initiative, p.4.

- ^ Trenberth K. E. (May 2001), "Stronger Evidence of Human Influence on Climate: The 2001 IPCC Assessment" (PDF), Environment, vol. 43, no. 4, Heldref, p.11.

-

"Ch 7 Assessing Progress in Climate Science",

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in US NRC 2001, p. 22 - ^ Press flyer announcing 2007 report IPCC

- ^

"Synthesis report", Sec 6.1. Observed changes in climate and their effects, and their causes

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007 - ^

"Synthesis report", Treatment of uncertainty, in: Introduction

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007 - ^

"Synthesis report", Sec 6.2 Drivers and projections of future climate changes and their impacts

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007 - ^

"Synthesis report", Sec 6.3 Responses to climate change

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007 - ^

"Summary for Policymakers", 3. Projected climate change and its impacts

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007 - Future climate change, in UK Royal Society 2010, p. 10 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFUK_Royal_Society2010 (help)

- Academia Brasileira de Ciéncias & others 2007

- Academia Brasileira de Ciéncias & others 2008

- Academia Brasileira de Ciéncias & others 2009

- NASAC 2007

- IAMP 2010

-

- Academia Nacional de Medicina de Buenos Aires

- Academy of Medical Sciences of Armenia

- Austrian Academy of Sciences

- Bangladesh Academy of Sciences

- Academia Boliviana de Medicina

- Brazilian Academy of Sciences

- Cameroon Academy of Sciences

- Chinese Academy of Engineering

- Academia Nacional de Medicina de Colombia

- Croatian Academy of Medical Sciences

- Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts

- Academy of Scientific Research and Technology, Egypt

- Académie Nationale de Médecine, France

- The Delegation of the Finnish Academies of Science and Letters

- Union of German Academies of Sciences and Humanities

- Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher, Leopoldina

- Academia de Ciencias Medicas, Fisicas y Naturales de Guatemala

- Hungarian Academy of Sciences

- Indonesian Academy of Sciences

- Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei

- TWAS, academy of sciences for the developing world

- Islamic World Academy of Sciences

- Science Council of Japan

- African Academy of Sciences

- Kenya National Academy of Sciences

- The National Academy of Sciences, Rep. of Korea

- Akademi Sains Malaysia

- National Academy of Medicine of Mexico

- Nigerian Academy of Science

- National Academy of Science and Technology, Philippines

- Polish Academy of Sciences

- The Caribbean Academy of Sciences

- Russian Academy of Medical Sciences

- Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts

- Academy of Science of South Africa

- National Academy of Sciences of Sri Lanka

- Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- The Tanzania Academy of Sciences

- Thai Academy of Science and Technology

- Turkish Academy of Sciences

- Uganda National Academy Sciences

- Academy of Medical Sciences, UK

- Institute of Medicine, US NAS

- PBL & others 2009

- PBL 2010

- Summary, in PBL & others 2009, p. 7

- ^ Executive summary, in PBL 2010, p. 9

- Summary, p.3, in US NRC 2010

- Section 3.2: Errors, in: Chapter 3: Results and discussion, in PBL 2010, pp. 35–37

- Fifth Assessment Report (AR5)

- IPCC climate report - your questions answered The UN body is to announce the findings of its fifth assessment report on the state of climate science in Stockholm Guardian 26 September 2013

- "IPCC – Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change". Ipcc.ch. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- ^ "IPCC – Activities". Ipcc.ch. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- IPCC SRES 2000

- Summary for Policymakers, in IPCC SRES 2000, p. 3

-

"Summary for Policymakers", Question 3

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC TAR SYR 2001 -

"Summary for Policymakers", 3. Projected climate change and its impacts

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007 -

Morita, T.; et al., "Ch 2. Greenhouse Gas Emission Mitigation Scenarios and Implications", 2.5.1.1 IPCC Emissions Scenarios and the SRES Process

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC TAR WG3 2001 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFIPCC_TAR_WG32001 (help) -

"Synthesis report", 3.1 Emissions scenarios

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007 - "Ch 3. Review of Major Climate-Change Scenario Exercises", Sec 3.1.1. Significance and use (PDF), in Parson & others 2007, p. 31

- "Ch 3. Review of Major Climate-Change Scenario Exercises", Sec 3.1.2. Criticisms and controversies (PDF), in Parson & others 2007, pp. 35–38

- "Ch 3. Review of Major Climate-Change Scenario Exercises", Sec 3.1.2. Criticisms and controversies: Exchange rates: PPP versus MER (PDF), in Parson & others 2007, p. 36

- "Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation – SRREN". Srren.ipcc-wg3.de. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "IPCC". Ipcc-wg2.gov. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Program". Ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "Revised 1996 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories". Ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "IPCC 2006 GLs". Ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Unfccc.int. 22 February 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- IPCC. Activities — Assessment Reports. Retrieved 20 December 2006. Web archive 21 February 2010

- IPCC. Activities — Workshops & Expert Meetings. Retrieved 20 December 2006. Web archive 21 February 2010

- IPCC AR4 WGI

- "Press Release". Web.archive.org. 11 June 2007. Archived from the original on 11 June 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "This site has moved to: http://www". Gtp89.dial.pipex.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - "Welcome to the IPCC Data Distribution Centre". Ipcc-data.org. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "IPCC – National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme". Ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "2007 Nobel Peace Prize Laureates". Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- "Scientists Send Letter to Congress and Federal Agencies Supporting IPCC". Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Shapiro, Harold T. (30 August 2010). "Review of the IPCC : An Evaluation of the Procedures and Processes of the InterGovernmental Panel on Climate Change". InterAcademy Council. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.327.5965.510, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with