This is an old revision of this page, as edited by TruthAboveEverything (talk | contribs) at 01:58, 28 October 2013. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:58, 28 October 2013 by TruthAboveEverything (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Alternative medicine | |

|---|---|

| Claims | Electrical stimulation of the scalp can relieve various psychological disorders. |

Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation (CES) Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation (CES) is an FDA cleared psychiatric treatment that applies a small, pulsed microcurrent to the head to treat the symptoms of insomnia, anxiety and depression. CES received FDA-Clearance in 1976, causes no serious side effects, and may be used safely with or without medication. Scores of well-controlled studies have been published on CES safety and effectiveness and the technology is endorsed by leading doctors in the field of psychiatry, including Jerrold Rosenbaum, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Mitchell Rosenthal, MD, of Phoenix House, Robert Cancro, MD, of NYU Medical School, and Igor Galynker, Associate Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Beth Israel

History

"Electrotherapy" has been in use for at least 2000 years, as shown by the clinical literature of the early Roman physician, Scribonius Largus, who wrote in the Compositiones Medicae of 46 AD that his patients should stand on a live black torpedo fish for the relief of a variety of medical conditions, including gout and headaches. Claudius Galen (131 - 201 AD) also recommended using the shocks from the electrical fish for medical therapies.

Low intensity electrical stimulation is believed to have originated in the studies of galvanic currents in humans and animals as conducted by Giovanni Aldini, Alessandro Volta and others in the 18th century. Aldini had experimented with galvanic head current as early as 1794 (upon himself) and reported the successful treatment of patients suffering from melancholia using direct low-intensity currents in 1804.

Modern research into low intensity electrical stimulation of the brain was begun by Leduc and Rouxeau in France (1902). In 1949, the Soviet Union expanded research of CES to include the treatment of anxiety as well as sleeping disorders.

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was common for physicians and researchers to place electrodes on the eyes, thinking that any other electrode site would not be able to penetrate the cranium. It was later found that placing electrodes on the earlobes was far more convenient, and quite effective.

CES was initially studied for insomnia and called electrosleep therapy; it is also known as Cranial-Electro Stimulation and Transcranial Electrotherapy.

In 1972, a specific form of CES was developed by Dr. Margaret Patterson, providing small pulses of electric current across the head to ameliorate the effects of acute and chronic withdrawal from addictive substances. She named her treatment "NeuroElectric Therapy (NET)".

Effectiveness

In 2006, Dr. Ray B. Smith, Ph.D., published one of several meta-analysis on the body of research performed with CES devices. Eighteen studies, in which a total of 648 patients with various types of sleep disorders were treated with CES, were meta-analyzed in order to get a more confident look at the effectiveness of CES for treating this condition. The result of the analysis showed that the overall effectiveness of CES was 62% improvement, and when the studies were weighted in terms of the rigorousness of the study design employed, the improvement was found to be an even stronger 67%. The results also indicated that a wide range of sleep disorders can be expected to respond to CES treatment. Eighteen studies were analyzed, in which a total of 853 patients were treated with CES for depression. The result of the analysis showed that the overall effectiveness of CES was 47% improvement. The results indicated that various types of depression, which accompany a wide range of clinical syndromes can be expected to respond, sometimes dramatically to CES treatment. Thirty-eight studies were analyzed, in which a total of 1,495 patients were treated with CES for anxiety. The result of the analysis showed that the overall effectiveness of CES was 58% improvement. The results indicated that various types of anxiety, which accompany a wide range of clinical syndromes, may be expected to respond, often dramatically to CES treatment.

Fifteen studies were analyzed, in which a total of 535 patients were treated for the drug abstinence syndrome with CES. The result of the analysis showed that the overall effectiveness of CES was 60% improvement. Researchers earlier received a strong impetus to study CES in substance abuse patients when in the 1970s it was found that the abstinence syndrome, including such features as depression, anxiety and insomnia, was seen to come under control very quickly with CES. Serendipitously it was also discovered that whathad up until the 1970s been termed “permanent brain damage” in these patients responded to three weeks of CES treatment by bringing these patients back within their normal functioning range.

The Following Table reflects the Study Design, showing that there were various approaches to conducting them.

| Study Design | No. Of Studies | No. Of Subjects | Mean Improvement | Mean Range of Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double Blind | 31 | 1,076 | 56% | 23%-81% |

| Single Blind | 8 | 519 | 62% | 23%-93% |

| Open Clinical | 22 | 1,162 | 56% | 27%-83% |

| Crossover | 6 | 153 | 57% | 8%-95% |

| Totals/Av. | 67 | 2,910 | 58% | 22%-90% |

Soroush Zaghi et al. published an article in the journal The Neuroscientist, finding that CES increases the production of serotonin, GABA, and endorphins. These neurochemical changes explain any positive effects that might be experienced from CES.

A 1995 meta-analysis by Klawansky et al. published in Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease "showed CES to be significantly more effective than sham treatment (p < .05)", but noted that 86% of the studies included in the review were inadequately blinded and the experimenter "knew which patients were receiving CES or sham treatment." The notable result arising from the meta-analysis of studies for each of four indications was that the pooled result for the eight studies analyzing the treatment of anxiety with continuous scales was in favor of CES at a statistically significant level (effect size estimate = -5883; 95% confidence interval = -.9503, -.2262). The result in favor of CES remained significant when the three studies that provided no convincing sensation in their sham protocol were dropped. Pooling the two independently positive studies on headache yielded a positive effect size of .6843 with confidence interval (.0872, 1.2813). Pooling did not alter results of studies that were independently negative (brain dysfunction, insomnia, and headache). Studies on pain under anesthetic were independently positive and were not pooled for technical statistical reasons.

Supporters and prescribers of the therapy include Jerrold Rosenbaum, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Mitch Rosenthal, MD, of Phoenix House, Robert Cancro, MD, of NYU Medical School , researchers and industry experts , and notable members of military and veterans groups .

In an April 6, 2013 letter to the FDA, Michael J. Davis (SS, DFC, PH), a retired member of the US Army wrote on behalf of the Vietnam Combat Veterans, Ltd., which represent 300,000+ combat veterans expressing that the “Vietnam Combat Veterans, Ltd.; VET-NET asks, in the strongest possible terms, that the FDA approve the reclassification of CES devices in accordance with the applications requesting such reclassification that are presently under consideration” .

On February 12, 2012, Mitchell Rosenthal, M.D., former white house advisor on drug abuse, chair of The New York State advisory council on Drug Abuse, and the Founder of Phoenix House, one of the leading non-profit substance abuse agencies in the US, asserted in his testimony to the FDA for CES re-classification that nearly 23 million Americans who are in need of treatment for substance abuse would stand to significantly benefit from implementing CES technology into their treatment, especially when other means for treating client depression, anxiety, and insomnia are ineffective, all of which are common symptoms of substance abuse. His experience with CES as a part of treatment yielded positive results, noting higher retention rates and longer lengths of treatment, which are positively correlated with a higher probability in successful rehabilitation. He noted CES’s thirty year history of safety and effectiveness when he urged the FDA panel to re-classify CES devices to class II, acknowledging that it is a low risk device .

Brigadier Stephen Xenakis, M.D., a retired brigadier general and Army medical corps officer with 28 years of active service, adjunct Clinical Professor at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences with an active clinical and consulting practice, and former senior adviser to the Department of Defense on neurobehavioral conditions and medical management declared his stance on CES technology in his testimony to the FDA for re-classification on February 10, 2012. In regards to PTSD, he spoke on the gaps in clinical care and research, stating that medications fail to treat a significant amount of patients. He asserted that CES is safe, cost efficient, practical, necessary, and effective. In addition, CES is convenient enough to use out of the privacy of one’s home, and portable enough to use in areas of combat, making it preferable to other forms of treatment that would require hospital visits and doctor’s administration .

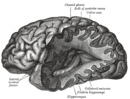

Computer modeling predictions using a highly detailed anatomical model show that CES induces significant currents in cortical, sub-cortical structures like thalamus,insula,and hypothalamus, and brain-stem structures.

A bibliography by Kirsch (2002) listed 126 scientific studies of CES involving human subjects and 29 animal studies. An estimated 145 human studies have been completed, encompassing over 8800 people receiving active CES.

A study published in Journal of Cognitive Rehabilitation found that 86% of the subjects tested showed improvements in their depression, 86% in state anxiety, and 90% in trait anxiety. An 18 month follow up found 18 of the original 23 subjects available to return for testing. Overall, they performed as well or better than in the original study.

A pilot study showed that CES reduced the symptom burden of generalized anxiety disorder, with a decrease in Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS) across a 6 week study, but the study had a small sample of participants and no control group.

A meta-analysis of eight randomly controlled trial studies assessing the efficacy of CES on anxiety found that CES improved anxiety significantly as compared with placebo/sham treatment.

A systematic review which assessed 34 controlled trials involving a total of 767 CES patients and 867 control patients reported that in 77% of studies (26 of 34), CES was found to significantly reduce anxiety.

Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation devices are proposed to treat serious (in the case of suicidal patients) or irreversibly debilitating psychiatric conditions in patients suffering from depression, anxiety and insomnia, often in association with Post Traumatic Stress and substance abuse.CES devices have been prescribed for the treatment of soldiers and veterans with neuropsychiatric conditions who do not respond to psychotropic medications or do not comply with prescriptions. The Veterans Affairs study published in JAMA entitled “Adjunctive Risperidone Treatment for Antidepressant-Resistant Symptoms of Chronic Military Service–Related PTSD: A Randomized Trial” documents the limited efficacy of drugs in the treatment of depression in soldiers who are suffering from PTSD .

CES devices are used and prescribed at Army, Navy and VA (Veteran’s Affairs) Hospitals to treat anxiety, depression and insomnia . COL. Dallas Hack, MD, the Director of the Combat Casualty Care Research Program for the US Army, has officially requested that the FDA perform an Expedited Review of CES Reclassification . Hundreds of thousands of Americansoldiers who served in Iraq and Afghanistan suffer from depression, anxiety and insomnia associated with Post Traumatic Stress. A 2011 study published by the Journal of theAmerican Medical Association entitled "Adjunctive Risperidone Treatment for Antidepressant-Resistant Symptoms of Chronic Military Service—Related PTSD" provedthat several common anti-depressants are no more effective at treating soldiers with PTSD than placebo. As a result, there is an enormous need for non-drug alternative treatment options such as CES for the military population .

CES research has been conducted in pain management and the reduction of anxiety in patients undergoing dental procedures.

The Department of Veterans Affairs has released data stating 10,000 combat veterans with PTSD entered VA hospitals every three months in 2011, resulting in over 200,000 patients with this disorder. The increase is more than 5% per quarter. Unfortunately, the demand for mental health care will likely continue to rise as thousands oftroops return home .

A 3-week randomized controlled study which looked at insomnia in fibromyalgia patients found significant improvement in sleeping patterns. In a longitudinal insomnia study, subjects showed improvement of symptoms during a two-year follow-up (p<0.0008).

Several studies published in peer reviewed medical journals have found statistically significant results using CES in the treatment of depression, and anxiety.

Regulation

CES is a prescription device which became available in the United States in 1963 as Electrosleep. It was grandfathered into modern FDA regulation in 1976 as a Class III device under the Medical Device Amendments Act of 1976 when FDA changed the name to Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation. During the 48 year history in the U.S., there has been no evidence that CES has caused any injury or death .

In the United States, CES technology is classified by the Food and Drug Administration as Class III medical devices and must be dispensed by or on the order of a licensed healthcare practitioners, i.e. a physician, psychiatrist or nurse practitioner; psychologists, physician assistants, and occupational therapists who have an appropriate electrotherapy license may prescribe CES, dependent upon state regulations.. Currently, less than 50% of soldiers are helped with traditional treatments. For years, CES has been withheld reclassifying these devices as Class I or Class II medical devices, which would allow private insurance companies to reimburse for them and no longer deem experimental .

The two large manufacturers of CES devices, Fisher Wallace Laboratories and Electromedical Products International, have petitioned the FDA to reclassify CES devices from Class III to Class II or Class I. These petitions have received broad support from the psychiatric comminity, members of Congress, patient groups and the US Army. Detractors of CES point to the fact that most published studies have relatively small subject sizes and were performed between the 1970’s – 1990’s. Supporters of the technology point to the fact that the potential bennefits of using CES outweighs the potential risks, and that the research that has been performed to date, while imprfect, provides a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness. The success that CES has in treating substance abuse patients is well documented in multiple published studies. These devices offer a particular advantage in treating patients who should not take antidepressants (such as patients taking methadone) or who have a history of abusing prescription medication. Organizations such as Phoenix House, Samaritan Village and Day Top Village are successfully using CES devices to treat their patients and improve patient retention. CES devices are over-the-counter in Europe, cause no serious side effects and are safe to use in conjunction with medication. They have been widely used in the United States for decades without any serious adverse events .

Proposed mechanism of action

The exact mechanism of action of CES remains unclear but it is proposed that CES reduces the stress that underpins many emotional disorders. The proposed mechanism of action for CES is that the pulses of electric current increase the ability of neural cells to produce serotonin, dopamine DHEA endorphins and other neurotransmitters stabilizing the neurohormonal system.

It has been proposed that during CES, an electric current is focused upon the hypothalamic region; during this process, CES electrodes are placed on the ear at the mastoid, near to the face. Computer modeling suggest that current of similar magnitudes maybe induced in both cortical and sub-cortical regions. The prediction that CES induced current intensities in the sub-cortical structures are not sufficiently decreased from the cortical structures is potentially clinically meaningful.

It has been suggested that the current results in an increase of the brain's levels of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, and a decrease in its level of cortisol. After a CES treatment, users are in an "alert, yet relaxed" state, characterized by increased alpha and decreased delta brain waves as seen on EEG.

See also

References

- Rosenthal, Mitchell S., M.D. "Food and Drug Administration Re-Classification." Letter to Christy Foreman. 25 Apr. 2012. Regulations.gov. N.p., 25 Apr. 2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2013. http:// www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=FDA-2011-N-0504-0186

- Galynker, Igor, M.D., PhD. "Re: Reclassification of Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation Devices." Letter to Christy Foreman. 11 Apr. 2013. Regulations.gov. N.p., 11 Apr. 2013. Web. 5 Oct. 2013. <http:// www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=FDA-2013-N-0195-0059>.

- Cancro, Robert, M.D. "RE: Reclassification of Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation Devices." Letter to Christy Foreman. 11 Jan. 2012. New York University School of Medicine, 11 Jan. 2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2013. <https://www.dropbox.com/sh/wak1fwntq75wqt5/UWy4OP9f3Z/Dr.Cancro-To-FDA.pdf>.

- Rosenbaum, Jerrold F., M.D. "Food and Drug Administrative Center for Devices and Radiological Health." Letter to Christy Foreman. 5 Jan. 2012. Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts General Hospital, 5 Jan. 2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2013. <https://www.dropbox.com/sh/wak1fwntq75wqt5/p0sk10rXIe/ Dr.Rosenbaum-to-FDA.pdf> .

- Hack, Dallas C., COL, M.D. "Request for Expedited Review of Reclassification for Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation Devices, FDA-2011-N-0504." Letter to Food and Drug Administration. 13 Jan. 2012. Department of the Army, 13 Jan. 2012. Web. 7 Oct. 2013. <http://www.regulations.gov/#! documentDetail;D=FDA-2011-N-0504-0184>.

- Stillings D. A Survey Of The History Of Electrical Stimulation For Pain To 1900 Med.Instrum 9: 255-259 1975

- ^ Zaghi S, Acar M, Hultgren B, Boggio PS, Fregni F. (2009). Noninvasive brain stimulation with low-intensity electrical currents: putative mechanisms of action for direct and alternating current stimulation. The Neuroscientist

- Leduc S. La narcose electrique. Ztschr. fur Electrother., 1903, XI, 1: 374-381, 403-410.

- Leduc S., Rouxeau A. Influence du rythme et de la period sur la production de l'inhibition par les courants intermittents de basse tension. C.R. Seances Soc.Biol., 1903,55, VII-X : 899-901

- L.A. Geddes (1965). Electronarcosis. Med.Electron.biol.Engng. Vol.3, pp. 11–26. Pergamon Press

- Гиляровский В.А., Ливенцев Н.М., Сегаль Ю.Е., Кириллова З.А. Электросон (клинико-физиологическое исследование). М., "Медгиз", 2 изд. М., "Медгиз", 1958, 166 с.

- Bystritsky, A, Kerwin, L and Feusner, J (2008). "A pilot study of cranial electrotherapy stimulation for generalized anxiety disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 69 (3): 412–417. doi:10.4088/JCP.v69n0311. PMID 18348596.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Appel, C. P. (1972). Effect of electrosleep: Review of research. Goteborg Psychology Report, 2, 1-24

- ^ doi:10.1300/J184v09n02_02

- Iwanovsky, A., & Dodge, C. H. (1968). Electrosleep and electroanesthesia–theory and clinical experience. Foreign Science Bulletin, 4 (2), 1-64

- doi:10.1007/s11940-008-0040-y

- Dr. Margaret A. Patterson. Effects of Neuro-Electric Therapy (N.E.T.) In Drug Addiction: Interim Report. Bull Narc. 1976 Oct-Dec;28(4):55-62. PubMed PMID 1087892.

- Patterson MA. Electrotherapy: addictions and neuroelectric therapy. Nurs Times. 1979 Nov 29;75(48):2080-3. PubMed PMID 316129.

- Smith, Ray B., PhD. "Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation: A Study of Its First Fifty Years, Plus Three." N.p., 2006. Web. <http://www.fisherwallace.com/uploads/meta-analysis/ 02%20Cranial%20Electrotherapy%20Stimulation%20-%20%20Ray%20B%20Smith.pdf>.

- Smith, Ray B., PhD. "Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation: A Study of Its First Fifty Years, Plus Three." N.p., 2006. Web. <http://www.fisherwallace.com/uploads/meta-analysis/ 02%20Cranial%20Electrotherapy%20Stimulation%20-%20%20Ray%20B%20Smith.pdf>.

- Soroush Zaghi, Mariana Acar, Brittney Hultgren, Paulo S. Boggio, and Felipe Fregni. " Noninvasive Brain Stimulation with Low-Intensity Electrical Currents: Putative Mechanisms of Action for Direct and Alternating Current Stimulation." Neuroscientist. 2010 Jun;16(3):285-307

- ^ Sidney Klawansky (July 1995). "Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials of Cranial Electrostimulation: Efficacy in Treating Selected Psychological and Physiological Conditions". Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 183 (7): 478–484.

- Rosenthal, Mitchell S., M.D. "Food and Drug Administration Re-Classification." Letter to Christy Foreman. 25 Apr. 2012. Regulations.gov. N.p., 25 Apr. 2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2013. http:// www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=FDA-2011-N-0504-0186

- Galynker, Igor, M.D., PhD. "Re: Reclassification of Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation Devices." Letter to Christy Foreman. 11 Apr. 2013. Regulations.gov. N.p., 11 Apr. 2013. Web. 5 Oct. 2013. <http:// www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=FDA-2013-N-0195-0059>.

- Cancro, Robert, M.D. "RE: Reclassification of Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation Devices." Letter to Christy Foreman. 11 Jan. 2012. New York University School of Medicine, 11 Jan. 2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2013. <https://www.dropbox.com/sh/wak1fwntq75wqt5/UWy4OP9f3Z/Dr.Cancro-To-FDA.pdf>.

- Rosenbaum, Jerrold F., M.D. "Food and Drug Administrative Center for Devices and Radiological Health." Letter to Christy Foreman. 5 Jan. 2012. Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts General Hospital, 5 Jan. 2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2013. <https://www.dropbox.com/sh/wak1fwntq75wqt5/p0sk10rXIe/ Dr.Rosenbaum-to-FDA.pdf>.

- Hack, Dallas C., COL, M.D. "Request for Expedited Review of Reclassification for Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation Devices, FDA-2011-N-0504." Letter to Food and Drug Administration. 13 Jan. 2012. Department of the Army, 13 Jan. 2012. Web. 7 Oct. 2013. <http://www.regulations.gov/#! documentDetail;D=FDA-2011-N-0504-0184>.

- Astone-Twerel, Janetta, PhD. "REclassification of CES Devices." Letter to The Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 11 Apr. 2013. Samaritan Village, Inc., 11 Apr. 2013. Web. 7 Oct. 2013. <http:// www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=FDA-2013-N-0195-0060>.

- Lindstrom, Wayne W., PhD. "RE: The Reclassification of Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation "CES"" Letter to Margaret Hamburg. 11 June 2013. Mental Health America, 11 June 2013. Web. 05 Oct. 2013. <https://www.dropbox.com/sh/wak1fwntq75wqt5/yY7ljClNwR/MentalHealthAmerica-to-FDA.pdf>.

- Rosenthal, Mitchell S., M.D. "Food and Drug Administration Re-Classification." Letter to Christy Foreman. 25 Apr. 2012. Regulations.gov. N.p., 25 Apr. 2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2013. http:// www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=FDA-2011-N-0504-0186

- Hack, Dallas C., COL, M.D. "Request for Expedited Review of Reclassification for Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation Devices, FDA-2011-N-0504." Letter to Food and Drug Administration. 13 Jan. 2012. Department of the Army, 13 Jan. 2012. Web. 7 Oct. 2013. <http://www.regulations.gov/#! documentDetail;D=FDA-2011-N-0504-0184>.

- Davis, Michael J., SS, DFC, PH. "Support for Reclassification of Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation (CES) Devices to Class II." Letter to Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health. 6 Apr. 2013. VET-NET. Vietnam Combat Veterans, Ltd., 6 Apr. 2013. Web. 6 Oct. 2013. <http:// www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=FDA-2013-N-0195-0039>.

- Davis, Michael J., SS, DFC, PH. "Support for Reclassification of Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation (CES) Devices to Class II." Letter to Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health. 6 Apr. 2013. VET-NET. Vietnam Combat Veterans, Ltd., 6 Apr. 2013. Web. 6 Oct. 2013. <http:// www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=FDA-2013-N-0195-0039>.

- Fisher Wallace Laboratories. “Dr. Mitchell Rosenthal at FDA Hearing on CES.” Online Video Clip. YouTube. YouTube, 28 Mar. 2012. Web. 12 Oct. 2013.

- Fisher Wallace Laboratories. “Dr. Xenakis at FDA Hearing for CES.” Online Video Clip. YouTube. YouTube, 26 Mar. 2012. Web. 11 Oct. 2013.

- ^ Datta, A., Dmochowski, J.P.,Guleyupoglu, B.,Bikson, M., Fregni, F.(2012) Cranial electrotherapy stimulation and transcranial pulsed current stimulation:A computer based high-resolution modeling study.Neuroimage.

- Kirsch, D. L. (2002). The science behind cranial electrotherapy stimulation. Edmonton, Alberta: Medical Scope Publishing

- Kirsch, Daniel L., "Science Behind Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation", 2nd edition, 2002

- Smith, Ray B, "Cranial electrotherapy stimulation in the treatment of stress related cognitive dysfunction, with an eighteen month follow up." Journal of Cognitive Rehabilitation, 17(6):14-18, 1999.

- Bystritsky, Alexander, Kerwin, Lauren and Feusner, Jamie. (2008 url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18348596). "A pilot study of cranial electrotherapy stimulation for generalized anxiety disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 69: 412–417. doi:10.4088/JCP.v69n0311. PMID 18348596.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Missing pipe in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - De Felice EA. Cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES) in the treatment of anxiety and other stress-related disorders: A review of controlled clinical trials. Stress Medicine. 1997;13(1):31-42.

- Hack, Dallas C., COL, M.D. "Request for Expedited Review of Reclassification for Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation Devices, FDA-2011-N-0504." Letter to Food and Drug Administration. 13 Jan. 2012. Department of the Army, 13 Jan. 2012. Web. 7 Oct. 2013. <http://www.regulations.gov/#! documentDetail;D=FDA-2011-N-0504-0184>.

- Fisher, Charles A. "Citizen's Petition." Letter to Division of Dockets Management, FDA. 8 Mar. 2012. Fisher Wallace Citizen's Petition. Regulations.gov, 8 Mar. 2012. Web. 5 Oct. 2013. <http:// www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=FDA-2012-P-0260-0001>.

- Hack, Dallas C., COL, M.D. "Request for Expedited Review of Reclassification for Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation Devices, FDA-2011-N-0504." Letter to Food and Drug Administration. 13 Jan. 2012. Department of the Army, 13 Jan. 2012. Web. 7 Oct. 2013. <http://www.regulations.gov/#! documentDetail;D=FDA-2011-N-0504-0184>.

- Fisher, Charles A. "Citizen's Petition." Letter to Division of Dockets Management, FDA. 8 Mar. 2012. Fisher Wallace Citizen's Petition. Regulations.gov, 8 Mar. 2012. Web. 5 Oct. 2013. <http:// www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=FDA-2012-P-0260-0001>.

- Kirsch, D. & , Smith, R.B. (2000). The use of cranial electrotherapy stimulation in the management of chronic pain: A review. NeuroRehabilitation, 14, 85-94

- P. Cevei, M. Cevei and I. Jivet. (2011) Experiments in Electrotherapy for Pain Relief Using a Novel Modality Concept. IFMBE, Volume 36, Part 2, 164-167. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-22586-4_35

- Winick, Reid L. Cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES): a safe and effective low cost means of anxiety control in a dental practice. General Dentistry. 47(1):50-55, 1999.

- Maloney, Carolyn B. "FDA ReClassification." Letter to Margaret Hamburg. 12 Jan. 2012. Congress of the United States, 12 Jan. 2012. Web. 5 Oct. 2013. <http://www.regulations.gov/#! documentDetail;D=FDA-2011-N-0504-0185>.

- Lichtbroun, A.S., Raicer, M.M.C. and Smith, R.B. The treatment of fibromyalgia with cranial electrotherapy stimulation. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 7(2):72-78, 2001.

- Weiss, Marc F. The treatment of insomnia through use of electrosleep: an EEG study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 157(2):108 120, 1973

- Matteson M et al. An exploratory investigation of CES as an employee stress management technique. Journal of Health and Human Resource Administration. 9:93 109, 1986

- Smith R et al. Electrosleep in the management of alcoholism. Biological Psychiatry. 10(6):675 680, 1975

- Smith R et al. The use of transcranial electrical stimulation in the treatment of cocaine and/or polysubstance abuse, 2002

- Rosenthal SH. Electrosleep: A double-blind clinical study. Biological Psychiatry. 1972;4(2):179-185.

- Philip P, Demotes-Mainard J, Bourgeois M, Vincent JD. Efficiency of transcranial electrostimulation on anxiety and insomnia symptoms during a washout period in depressed patients. A double-blind study. Biol Psychiatry. Mar 1 1991;29(5):451-456

- Sousa AD, P.C. Choudhury. A psychometric evaluation of electrosleep. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 1975;17:133-137

- Gibson TH, Donald E. O'Hair. Cranial application of low level transcranial electrotherapy vs. relaxation instruction in anxious patients. American Journal of Electromedicine. 1987;4(1):18-21

- Ryan JJ SG. Effects of transcerebral electrotherapy (electrosleep) on state anxiety according to suggestibility levels. Biological Psychiatry. 1976;11(2):233-237

- Maloney, Carolyn B. "FDA ReClassification." Letter to Margaret Hamburg. 12 Jan. 2012. Congress of the United States, 12 Jan. 2012. Web. 5 Oct. 2013. <http://www.regulations.gov/#! documentDetail;D=FDA-2011-N-0504-0185>.

- 21CFR882.5800, Part 882 ("Neurological Devices")

- FDA medical device classifications

- Xenakis, M.D., Brigadier General (Ret) Stephen N., PhD. "It's Time to Move Beyond the Clichés." The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 16 Oct. 2013. Web. 19 Oct. 2013.

- Lindstrom, Wayne W., PhD. "RE: The Reclassification of Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation "CES"" Letter to Margaret Hamburg. 11 June 2013. Mental Health America, 11 June 2013. Web. 05 Oct. 2013. <https://www.dropbox.com/sh/wak1fwntq75wqt5/yY7ljClNwR/MentalHealthAmerica-to-FDA.pdf>.

- Cite error: The named reference

Smithwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Gilula MF, Kirsch DL. (2005). Cranial electrotherapy stimulation review: a safer alternative to psychopharmaceuticals in the treatment of depression. Journal of Neurotherapy, 9(2), 63-77.

- Gilula, M.F. & Kirsch, D.L. Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation Review: A Safer Alternative to Psychopharmaceuticals in the Treatment of Depression. Journal of Neurotherapy, Vol. 9(2) 2005. doi:10.1300/J184v09n02_02

- Kennerly, Richard. QEEG analysis of cranial electrotherapy: a pilot study. Journal of Neurotherapy (8)2, 2004.

External links

- A review of the technology and analysis of the research through 2006

- It's Time to Move Beyond the Clichés