This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Rex Germanus (talk | contribs) at 11:24, 1 July 2006. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 11:24, 1 July 2006 by Rex Germanus (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Battle of the Netherlands | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||||

| File:BATTLENETHERLANDS1.JPG Dutch soldiers during the battle of the Netherlands. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kingdom of the Netherlands | Nazi Germany | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Henry G. Winkelman, Jan Joseph Godfried baron van Voorst tot Voorst | Fedor von Bock (Army Group B) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

9 divisions, 676 guns, 1 tank (inoperational), 124 aircraft Total: 350,000 men |

22 divisions, 1,378 guns, 759 tanks, 1150 aircraft Total: 750,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

7,500 dead, missing or wounded, 343,250 captured |

4,000 dead, 3,000 wounded, 700 missing, 1400 captured | ||||||

The Battle of the Netherlands (Slag om Nederland in Dutch) was part of Case Yellow (Fall Gelb), the German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) and France during World War II. The battle lasted from 10 May 1940 until 17 May 1940, during which Nazi Germany conquered and occupied the Netherlands. The battle ended after the devastating bombing of Rotterdam by the Luftwaffe and the subsequent decision of the Dutch military to surrender to prevent other cities from suffering the same fate.

Background

Britain and France declared war on Germany in 1939 following the invasion of Poland, but no land operations in Europe occurred during the period of the Phony War, while both sides prepared their forces.

Although the Netherlands had been neutral during World War I, the sympathies during that conflict were more on the German side. Wars with Germany had been non-existent and even before the unification of the German nation in 1871 wars with German states had been extremely rare. Wars with the main allied parties on the Western Front (France and Britain) however had been overabundant, especially the recent actions by the British against the Boers (Descendants of Dutch immigrants) in South Africa (Once a Dutch colony) had been detrimental to the overall image of the Entente. An event well portraying this attitude was that of the asylum given to the German Emperor Wilhelm II after he fled to the Netherlands in 1918 and giving him a castle called Huis ter Doorn where he lived until his death in 1941. However this didn't by far mean the Dutch people weren't shocked by the atrocities committed against the Belgian civilian population by the German army. They in fact sheltered more than a million refugees.

When Hitler came to power, the Dutch began to rearm but much slower than other nations. The consecutive governments just didn't see, or wanted to see, Nazi Germany as a threat. Partly this was caused by a wish not to antagonise Germany; partly it was made inevitable by a policy of strict budgetary limits with which the conservative Dutch governments in vain tried to fight the Great Depression, which hit Dutch society particularly hard.

After the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 and the following outbreak of the Second World War, the Netherlands hoped to remain neutral just like they had done 25 years ago. To ensure this neutrality the Dutch army was mobilised and entrenched. Large sums (more than a billion guilders) were at last made available to re-equip the forces, but it proved very difficult to obtain the necessary materiel in wartime (especially as the Dutch ordered much of their new equipment in Germany).

The strategic position of the Low Countries, located between France and Germany on the uncovered flanks of their fortification lines, made them the logical route for an offensive by either side. The Entente tried to convince them not to wait for the inevitable German attack but join them first. Both the Belgians and Dutch refused however, even when the German attack plans fell into Belgian hands after a German aircraft crash in January 1940.

The French considered to violate their neutrality if they hadn't taken the allied side before the planned large allied offensive in the summer of 1941. After the German invasion of Norway and Denmark (both without a declaration of war) it became clear to the Dutch military that staying out of the conflict might prove impossible and they started to fully prepare for war, both mentally and physically, by taking counter-measures against a possible airborne assault. Most civilians however still cherished the illusion their country might be spared. To many people the attitude of the Dutch people and their leaders at this time might seem incredibly naive, but they hoped the restrained policy of the Entente and Central Powers during World War I might be repeated and tried to keep a low profile and to stay out of a war at all cost, a point of view that, with the figure of human life lost during the First World War, may well be understood.

The Dutch forces

In the Netherlands nearly all the material conditions were present for a successful defence: a dense population, wealthy, young, disciplined and well-educated; a geography favouring the defender and a strong technological and industrial basis including a not-inconsiderable armaments industry. However, these had not been exploited: while the German army at the time still had many shortcomings in equipment and training, compared to the Dutch army, one could say that it was David and Goliath. The myth of the German equipment advantage over the opposing armies in the Battle of France was in fact a reality in the case of the battle of the Netherlands. On the one hand there was the, in comparison, hypermodern German army, with tanks, dive bombers (such as the Stuka) and submachine guns and on the other hand the Dutch army, with as armoured forces only one tank (an inoperational French Renault FT-17), 39 armoured cars and five tankettes; an airforce consisting of mostly biplanes and infantry armed with bolt-action rifles made before the Great War. The Dutch government's attitude towards war was reflected in the state of the country's armed forces, which hadn't been properly rearmed since 1904.

The Dutch equipment shortages were so bad they actually limited the number of large units: there was just enough artillery to allow the formation of only eight infantry divisions (combined in four Army Corps) and one Light (i.e. motorised) Division. Apart from two independent brigades (Brigade A and Brigade B) all other troops were raised as light infantry "border battalions" that were in fact dispersed all over the territory to delay enemy movement. They made use of many lines of pillboxes without any depth. Real modern fortresses like the Belgian stronghold of Eben Emael were non-existent. In comparison Belgium despite a smaller manpower base fielded 23 divisions. After September 1939 desperate efforts were made to improve the situation, but with very little result. Germany, for obvious reasons, delayed its deliveries; France was hesitant to equip an army that wouldn't unequivocally take its side and the one abundant source of readily available weaponry, the Soviet Union, was inaccessible as the Dutch exceptionally didn't recognise the communist regime.

On 10 May the most obvious deficiency of the Dutch Army lay in its shortage of armour. Whereas the other major participants had all a considerable armoured force, the Netherlands hadn't been able to obtain the minimum of 140 modern tanks they found necessary. The single Renault tank, for which just a driver had been trained and which had the sole task of testing antitank-obstacles, remained the only example of its kind. There were two squadrons of armoured cars, each with a dozen Landsverk vehicles; another dozen DAF M39 cars were in the process of being fitted with armament. A single platoon of five Carden-Loyd Mark VI tankettes used by the Artillery completed the list of Dutch armour.

The Dutch Artillery had available a total of 676 howitzers and field guns: 310 Krupp 75 mm field guns, partly produced in licence; 52 105 mm Bofors howitzers, the only really modern pieces; 144 obsolete Krupp 125 mm guns; 40 150 mm sFH13's; 72 Krupp 150 mm L/24 howitzers and 28 Vickers 152 mm L/15 howitzers. Many of these could only fire black powder shells, that couldn't really detonate. As antitank-guns 386 Böhler 47 mm L/39's were available; another 300 antiquated 6 Staal and 8 Staal field guns performed the same role for the covering forces. None of the 220 modern pieces ordered in Germany had been delivered at the time of the invasion.

The Dutch Infantry used about two thousand 6.5 mm Schwarzlose M.08 machine guns, partly licence produced, and 800 Vickers machine guns. Because many of these had to be fitted in the pillboxes, each battalion had a heavy machine gun company of twelve for its only automatic weapons, the Dutch infantry squads were not equipped with an organic light machine gun, whereas the German divisions had 559 LMG's allocated to their squads. Also there were but six 80 mm mortars for each battalion. This lack of firepower at the lowest level was the main cause of the often poor fighting performance of the Dutch infantry.

The Dutch airforce on 10 May operated a fleet of 155 aircraft: 28 Fokker G.1 twin-engined destroyers; 31 Fokker D.XXI and seven Fokker D.XVII fighters; ten twin-engined Fokker T.V, fifteen Fokker C.X and 35 Fokker C.V light bombers, twelve Douglas DB-8 divebombers and seventeen Koolhoven FK-51 reconnaissance aircraft — thus 74 of the 155 aircraft were biplanes. Of these aircraft 121 were both operational and part of organic strength. Of the remainder the airforce school used three Fokker D.XXI, six Fokker D.XVII, a single Fokker G.I, a single Fokker T-V and seven Fokker C.V, along with several training airplanes. Another forty aircraft served with the marine air service.

Not only was the Dutch Army poorly equipped; it was also poorly trained. Before the war only a minority of eligible young men had actually been conscripted — and often the least fit as it was easy to be exempted unless you were unemployed. Those enlisted only served for 24 weeks, just enough to receive basic infantry training. After the mobilisation readiness only slowly improved: most time was spent constructing defences. By its own standards the Dutch Army in May 1940 was unfit for battle. It simply couldn't stage a major offensive, let alone execute manoeuvre warfare.

German generals and tacticians (and Hitler himself) had an equally low opinion of the Dutch forces and thought that even the core region of Holland proper would be conquered in less than a day; when the actual battle developed, however, it transpired that the German army was to be pinned down after three days by an army that, although undermanned and without proper arms, offered stiff resistance. Being informed of this situation Hitler got into one of his infamous furies and demanded that the Dutch cities should be bombed into ashes to force a capitulation.

Dutch defensive strategy

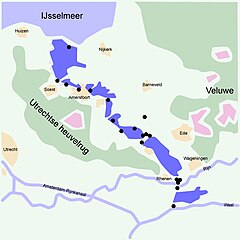

From the seventeenth century on, the Netherlands relied on a magnificent defensive system called the Water Line, which protected all of the major cities in the west of the country by flooding part of the countryside. In the late 19th century this line was modernised with fortresses and shifted somewhat to the east, beyond Utrecht. This new position was called the New Water Line. As the fortifications were outdated in 1940, it was reinforced with new pillboxes. The line was located at the extreme eastern edge of the area lying below sea level. This allowed the grounds before the fortifications to be easily inundated with a few feet of water, too shallow for boats, but deep enough to turn the soil into an impassable quagmire. The area west of the New Water Line was called Vesting Holland ('Fortress Holland'), the eastern flank of which was also covered by Lake IJssel and the southern flank protected by three broad parallel rivers: two effluents of the Rhine and the Meuse. It functioned as a National Redoubt. Before the war it was intended to fall back to this position almost immediately, inspired by the hope that Germany would only transgress the southern provinces on its way to Belgium and leave Holland proper untouched. In 1939 it was understood such an attitude basically posed an invitation to invade and made it impossible to negotiate with the Entente about a common defence. A more easterly Main Defence Line was constructed.

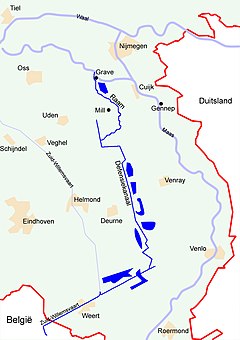

This second main defensive position was formed by the Grebbelinie (Grebbe Line), located at the foothills of an Ice Age moraine between Lake IJssel and the Lower Rhine, and the Peel-Raamstelling (Peel-Raam Position), located between the river Maas and the Belgian border along the Peel Marshes and the Raam rivulet. Fourth and Second Army Corps were positioned at the Grebbe Line; Third Army Corps at the Peel-Raam Position with the Light Division behind as a mobile reserve; Brigade A and B connected between the Lower Rhine and the Maas and First Army Corps was a strategic reserve in the Fortress Holland. All these lines were reinforced by pillboxes.

The defensive value of the Grebbe Line was limited at best. Apart from the pillboxes, it consisted mostly of trenches, protected by inundations. Also, the government had refused permission to clear the forest directly in front of the line, even though it offered ample cover for an attacking force.

The Light Division was the only partly motorised force in the Dutch Army; besides trucks it also employed large numbers of bicycles as a military means of transportation.

In front of this main defence line (MDL) was a covering line along the rivers IJssel and Maas, the IJsel-Maaslinie connected by positions in the Betuwe, again with pillboxes and lightly occupied by a screen of fourteen "border battalions". Late 1939 the Dutch Commander in Chief, General Izaak H. Reijnders, proposed to make use of the excellent defensive opportunities these rivers offered and shift to a more mobile strategy by first fighting a delaying battle with the Army Corps at the plausible crossing sites near Arnhem and Gennep to force the German divisions to spend much of their offensive power before they had reached the MDL. This was deemed too risky by the Dutch government; when Reijnders was also denied full military authority in the defence zones he offered his resignation and was replaced by General Henry G. Winkelman.

During the Phoney War the Netherlands officially adhered to a policy of strict neutrality. In secret however they negotiated with both Belgium and France to coordinate a common defence in case of a German invasion. This failed because of insurmountable differences of opinion about the question which strategy to follow. The Dutch wanted the Belgians to connect their defences to the Peel-Raam Position. The Belgians however wanted to fight along the Albert Canal. This created a dangerous gap. The French were invited to fill it. Now the French Commander in Chief General Maurice Gamelin was more than interested in including the Dutch in his continuous front as, like Bernard Montgomery four years later, he eventually hoped to circle around the Westwall when the Entente would launch its 1941 offensive. But he didn't dare to stretch his supply lines that far unless the Belgians and Dutch would take the allied side before the German attack. When both nations refused, Gamelin stated that he would occupy a connecting position near Breda. The Dutch however didn't fortify this "Orange Position": in secret they decided to abandon the Peel-Raam Position immediately at the onset of a German attack and withdraw Third Army Corps to the Linge to cover the southern flank of the Grebbe Line, leaving only a covering force behind.

After the German attack on Denmark and Norway in April 1940, when the Germans used large numbers of Fallschirmjäger or paratroopers, the Dutch command became worried about the possibility they too could become the victim of such a strategic assault. To repulse an attack, troops were positioned at the The Hague airfield of Ypenburg and the Rotterdam airfield of Waalhaven. These were reinforced by all tankettes and six of the 24 operational armoured cars. These specially directed measures were accompanied by more general ones: the Dutch had posted no less than 32 hospital ships throughout the country and fifteen trains to help make troop movements easier.

German strategy and forces

During the many changes in the operational plans for Fall Gelb it was at times considered to leave Fortress Holland alone, just as the Dutch hoped for. However Hermann Goering insisted on a full conquest as he needed the Dutch airfields against Britain satisfying Hitler in the process as he was afraid the Entente might after a partial defeat reinforce fortress Holland and use the airfields to bomb German cities and troops. A third reason for the complete conquest was that as the fall of France itself could hardly be taken for granted, it was for political reasons seen as desirable to obtain a Dutch capitulation, because yet another debacle for the policy of the Entente might well bring less hostile governments to power in Britain and France.

Though it was thus decided to conquer the whole of the Netherlands, few units could be made available for this task. The main effort of Fall Gelb would be made in the centre, between Namur and Sedan. The attack at central Belgium was only a feint; and the attack at Fortress Holland only a side show of this feint. Although of Army Group B 6th and 18th Army were deployed at the Dutch border, the first, much larger, force would move south of Venlo to Belgium, leaving just 18th Army under General Georg K.F.W von Küchler to defeat the Dutch main force. Of all German armies to take part in the operation this was by far the weakest. It contained only four regular infantry divisions (207th, 227th, 254th and 256th ID), assisted by three reserve divisions (208th, 225th, and 526th ID) that would not take part in the fighting. Six of these divisions were "Third Wave" units only raised in August 1939 from territorial Landwehr troops. They had few professional officers and were without any fighting experience apart from those among the 42% men over forty that were WWI-veterans. Like the Dutch Army most soldiers (88%) were insufficiently trained. The seventh was 526th ID, a pure security unit without any serious combat training. Even when accounting for the fact that the German divisions, with a nominal strength of 17,807 men, were half as large as their Dutch counterparts and possessed three times their effective firepower, the necessary numerical superiority for a successful offensive was simply lacking.

To remedy this, assorted odds and ends were used to reinforce 18th Army. The first of these was the only German cavalry division, aptly named 1st Kavalleriedivision. The mounted troops of this unit, accompanied by some infantry, were to occupy the weakly defended provinces east of the river IJssel and then try to cross the Afsluitdijk (enclosure dike) and simultaneously attempt a landing in Holland using barges to be captured in the small port of Stavoren. As both efforts were unlikely to succeed, the mass of regular divisions was reinforced by the SS-Verfügungsdivision (including SS-Standarten Der Führer, Deutschland and Germania) and Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, which would serve as assault infantry to breach the Dutch fortified positions. Still this added only four regiments to the equation. To ensure a victory the Germans resorted to more unconventional means.

The Germans had trained two airborne assault divisions. The first of these, 7th Fliegerdivision, consisted of paratroopers; the second, 22nd Luftlande-Infanteriedivision, of airborne infantry. First, when the main German effort was still to take place in Flanders, it was considered to use these for a crossing attempt over the river Scheldt near Ghent. This operation was consequently cancelled and it was now decided to use them to obtain an easy victory in the Netherlands. The airborne troops would on the first day secure the airfields around the Dutch seat of government, The Hague, and then capture that government, together with the Dutch High Command and the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina. German officers actually took lessons on how to address royalty on such occasions. Just in case this would not bring forth the desired immediate collapse, the bridges at Rotterdam, Dordrecht and Moerdijk would simultaneously be secured to allow a mechanised force to relief the airborne troops from the south. This force was to be 9th Panzerdivision, with 141 tanks, the weakest of all German armoured divisions, that was to exploit a breach in the Dutch MDL created by 254th and 256th ID on the Gennep - 's-Hertogenbosch axis. At the same time a binding offensive would be staged against the Grebbe Line in the east by 207th and 227th ID.

Of all operations of Fall Gelb this one most purely embodied the concept of a Blitzkrieg as the term was then understood: a Strategischer Überfall or strategic assault. And like Fall Gelb as a whole it was a gigantic gamble. The gamble would fail, but the Dutch would pay the price.

The Oster affair

The German population generally disliked the idea of attacking their Dutch neighbours, the Dutch didn't fight in the first world war and had even provided asylum for the German Emperor Wilhelm II and were indifferent against the German nazi regime. The German propaganda would therefore justify the invasion by the deliberate lie that it was merely a reaction to an Entente attempt to occupy the Low Countries. Many German officers had an aversion against the Nazi regime and shared the uneasiness about the invasion. One of them, Colonel Hans Oster, an Abwehr (German intelligence) officer, informed his friend, the Dutch military attaché in Berlin Major Gijsbertus J. Sas, of the date of the attack. The Dutch government in turn informed the Allies. As the date would be changed many times however, because it was postponed to wait for favourable weather conditions, the other nations became insensitive to the series of false alarms. When in the evening of 9 May Oster again phoned his friend saying just "Tomorrow, at dawn", only the Dutch troops were put on alert.

Prelude

The German plan assigned the invasion of the Netherlands and Belgium to Army Group B, under the command of Fedor von Bock. Originally, the plan assigned the main role to these forces, expecting the capture of the Low Countries and the Channel coast to provide bases for an attack on Britain. Army Group A, adjoining it to the south, was only expected to cover the flank of the attackers. However, several German generals, particularly Erich von Manstein, were unsatisfied with this limited offensive, and favored a deep penetration which took advantage of the speed of the unified Panzer armored divisions. In addition, a German staff officer crashed in Belgium on January 10, 1940 with a copy of the plan, which was not completely destroyed.

As a result, the Germans adopted an alternate plan which shifted nearly all the armored divisions to Army Group A. It was expected to cross northern France from the frontier to the coastline, encircling the British troops and separating them from the French. Besides obtaining the desired bases, Army Group B was now expected to attack Belgium and the Netherlands in order to draw Allied forces eastward into the developing encirclement.

Ironically, the Allies did not adjust their own battle plans or anticipate a change in German strategy as a result of their discovery. This omission contributed to the quick collapse of British and French defenses, preventing assistance to Belgium and the Netherlands.

The battle

10 May

In the morning of May the 10th 1940 the Dutch awoke by the sound of aircraft engines roaring in the sky. Nazi Germany had commenced operation Fall Gelb and attacked the Netherlands, Belgium, France and Luxembourg: in case of the Low Countries without a declaration of war given before hostilities.

In the night the Luftwaffe violated Dutch airspace, traversed it and then disappeared to the west, giving the Dutch the illusion that the operation was directed to England. But above the North Sea the enemy squadrons turned to the east again to stage a surprise attack on the Dutch airfields. Many aircraft were destroyed on the ground. The few Dutch planes that were able to take off shot down thirteen German aircraft, but most were lost during the fighting.

Immediately afterwards paratroopers were landed. Dutch AA batteries shot down numerous transport planes; the official numbers were later lost but an estimated 275 of these Ju-52 transport planes were destroyed in total during the Dutch campaign.

The attack on The Hague ended in utter failure. The paratroopers were unable to capture the main airfield, Ypenburg, in time for the airborne infantry to land safely in their Junkers. Though one armoured car had been damaged by a bomb, the other five Landsverks destroyed the first two waves of Junkers, killing most occupants. When the airstrip was blocked by wrecks the remaining waves aborted the landing and tried to find alternatives, often putting down their teams in meadows or on the beach, thus dispersing the troops. The auxiliary airfield of Ockenburg proved to be still under construction and unmetalled: those planes landing there sank away in the soft soil. In the end the paratroopers occupied Ypenburg but they were attacked immediately. An entire infantry regiment was stationed near the airfield. It deployed and with artillery support scattered the German defenders within hours; the airfield of Valkenburg was likewise reconquered, the remnant airborne troops taking refuge in the nearby village.

The attack on Rotterdam was much more successful. First five waterplanes landed in the heart of the city and unloaded assault teams that conquered the Willems Bridge to occupy bridgeheads over the Nieuwe Maas. Then the military airfield of Waalhaven, positioned south of the city on the island of IJsselmonde, was attacked by airborne forces. Here was an infantry battalion stationed, but so close to the airfield that the paratroopers landed in the midst of its positions. A confused fight followed. The first wave of Junkers was partly destroyed but this time the transports continued to land irrespective of losses. In the end the Dutch defenders and tankettes were overwhelmed. The German troops, steadily growing in numbers, began to move to the east to make contact with the paratroopers that had to occupy the two other vital bridges. At the Island of Dordrecht the Dordrecht bridge was captured but in the city itself the garrison held out. The long Moerdijk bridges over the broad Hollands Diep estuary connecting the island to North Brabant province were captured and bridgeheads fortified on both sides. In the village of Moerdijk a clear German war crime was committed when six captured officers were shot when their troops refused to surrender.

The Germans tried to capture the IJssel and Maas bridges intact, using commando teams of Brandenburgers that began to infiltrate over the Dutch border on 8 May. In the night of May the 10th they approached the bridges: a few men of each team were dressed as Dutch military police and pretended to bring in a group of German prisoners, so to fool the Dutch detonation teams. Some of these "military policemen" were real Dutchmen, members of the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging, the Dutch nazi party. Most of these attempts failed and the bridges were blown, on two occasions with Brandenburgers and all. The main exception was the Gennep railway bridge. Immediately an armoured train crossed it, drove right through the Peel-Raam Position at Mill and unloaded an infantry battalion behind the defence line.

The Dutch released the reports of German soldiers in disguise to the international news agencies. This caused a fifth column scare, especially in Belgium and France. However, unlike the situation later on in those two countries, in the Netherlands there was no mass exodus of civilian refugees, clogging the roads. Generally German soldiers behaved correctly towards the Dutch population, forming neat queues at the shops to buy goods rationed in Germany, such as chocolate.

After the generally failed assaults on the bridges, the German divisions began crossing attempts over the rivers IJssel and Maas. The first waves typically were destroyed, due to insufficient preparatory fire on the pillboxes. A secondary bombardment at most places destroyed the pillboxes and the infantry divisions crossed the river after building pontoon bridges; but at some, as Venlo, the attempt was aborted.

Even before the armoured train arrived, 3rd Army Corps had already been withdrawn from the Peel-Raam Position taking with it all the artillery, but each regiment left a battalion behind to serve, with fourteen "border battalions", as a covering force, called the "Peel Division". The corps joined six battalions already occupying the Waal-Linge line — and was thus brought up to strength again: but placing itself in a position in which it could have no further influence on the battle, a quarter of the field army had effectively rendered itself impotent.

The Light Division, based at Vught, was the only mobile reserve the Dutch Army possessed. It was decided to let it counterattack the German airborne landing on IJsselmonde. Its regiments thus biked over the Maas and Waal bridges and then turned left through the Alblasserwaard, to reach the Noord, the river separating this polder from IJsselmonde, in the evening. There they discovered that the only bridge, built in 1939, was left unguarded by the paratroopers, as the Germans because of outdated maps simply didn't know of its existence. It was however decided to postpone a crossing-attempt till the next day, when the artillery would be ready to support it. Not even a bridgehead was established.

Meanwhile, in the evening of the 10th, the first elements of the French 1st Mechanised Light Division had started to arrive in the Netherlands. This division was the most northern part of the French 7th Army; its mission was to ensure contact between the Vesting Holland and Antwerp.

11 May

Units of the German army had already reached the southern part of the Grebbe Line in the evening of the 10th. This section had not been inundated and therefore it was protected by a line of outposts (voorpostenlinie), manned by a battalion of infantry. At about half past three in the morning of the 11th, German artillery started shelling the outposts, followed at dawn by an attack by the SS regiment Der Führer. The outnumbered and inadequately armed battalion resisted as well as they could, but by evening, all outposts were in German hands. A nightly counterattack by a Dutch battalion failed, because it was fired on by Dutch troops that had not been notified.

In North Brabant, late on the 10th, the order had been given to retreat from the Peel-Raam Position to the Zuid-Willemsvaart, a canal some kilometres to the west. This meant leaving behind well-prepared positions, as well as all artillery and heavy machine guns. Moreover, the eastern bank of the canal was higher than the western bank, so that the defenders could not see the attackers. And finally, one sector of the western bank was left undefended; as this sector contained a bridge which was not demolished, the Germans were able to bypass the Zuid-Willemsvaart position with ease; by the end of the 11th, they had crossed the Zuid-Willemsvaart everywhere.

The planned attack by the Light Division also came to nothing. In the nick of time the bridge over the river Noord had been prepared for defense by the German paratroopers, and it proved impossible to cross. Several attempts to cross the river by boats also failed, and in the afternoon, the Light division was ordered to proceed to the Island of Dordrecht, where it arrived in the night.

Earlier during the day, several attempts were made to cross the Oude Maas, at Dordrecht and Barendrecht. There was no artillery support and the attacks were executed only hesitantly, and consequently all attempts failed. The reconnaissance units of the French 1st Mechanised Light Division attempted an attack on the Moerdijk bridge, but they were attacked by German planes and had to retreat.

In Rotterdam, despite important reinforcements, the Dutch did not succeed in dislodging the German paratroopers from their bridgehead on the northern bank of the Maas. Even though ordered to do so by General Student, the German commander in Rotterdam refused to evacuate this bridgehead, and despite bombardments by the two remaining Dutch bombers, the German paratroopers held fast. They also held fast around The Hague, where none of the attempts to eliminate the isolated paratroopers met with success.

The first days

Dutch optimism prevailed during the first three days of the battle, mainly because it all happened so fast that objective information was scarce. But nevertheless the people were convinced that if Germany would attack, Britain and France would come to the rescue in a matter of days and push the Germans back to Germany. The British and French did not come. The French army advanced beyond the Belgian-Dutch border but was pushed back all the way to Dunkirk several days after. Though there were small Dutch successes, the Germans pushed forward with great speed.

The last days

On May the 14th the Dutch situation seemed to have improved: although the Germans occupied most of the territory, the major cities and the bulk of the Dutch population were still under Dutch control. The German advance was halted at the Kornwerderzand (a line of pillboxes placed on the Afsluitdijk and impossible for them to breach); remaining German paratroopers were eliminated or surrounded and the German tanks seemed to have halted in the south at Rotterdam. The Dutch weren't the only ones aware of the situation. The German High Command and Hitler himself were worried. Hitler, who planned the attack on Holland together with Von Manstein, was terrified the British would land on the Dutch coast and use the Dutch airfields to launch attacks on Germany. And he demanded that the Dutch would be defeated within days.

The end

An ultimatum was delivered to the Dutch defenders of Rotterdam shortly after. It said that the city had to capitulate; if this was refused, it would be bombed. When the Dutch officer returned from signing the surrender, suddenly a massive group of bombers appeared; though red flash bullets were shot to warn the planes not to bomb Rotterdam (but they were not seen by the wing commander because of thick smoke coming from a burning oil tanker in the Rotterdam harbour), and one group returned to their base, the other larger group flew on and bombed Rotterdam. About 900 people died in the flames and the entire old city burned down.

When confronted by an ultimatum to capitulate or face the destruction of Utrecht as well, the Dutch Commander in Chief General Winkelman, devastated by the news of the destruction of Rotterdam, and realising by now that the British and French wouldn't come to help him, decided that the lives of the civilian population were worth more to him than a few more days of fighting. He decided that the Netherlands would surrender, with the exception of the province of Zeeland.

Aftermath

Following the Dutch defeat, Queen Wilhelmina established a government-in-exile in England. The German occupation officially began on May 17, 1940. It would take five years in which over 250,000 Dutchmen and women died before the Dutch regained their freedom.

References

- C.W. Star Busmann. Partworks and Encyclopedia of world war II

- Nederlands Instituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie (Dutch institute for war documentation).

- L. de Jong. The Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Second World War, part 3: May '40