This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 92.22.172.208 (talk) at 09:56, 4 November 2014 (→Discrimination). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 09:56, 4 November 2014 by 92.22.172.208 (talk) (→Discrimination)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

The gender pay gap (also known as gender wage gap, male–female income difference, gender gap in earnings, gender earnings gap, gender income difference) is the difference between male and female earnings expressed as a percentage of male earnings, according to the OECD.

The European Commission defines it as the average difference between men’s and women’s hourly earnings. It is generally suggested that the wage gap is due to a variety of causes, such as discrimination in hiring, differences in education choices, discrimination in salary negotiations, differences in the types of positions held by men and women, differences in the pay of jobs men typically go into as opposed to women (especially highly paid high risk jobs), and differences in amount of work experience, and breaks in employment.

However, there is still debate over what portion of the wage gap is due to explicit discrimination. It is estimated that around 40% of the wage gap is caused by discrimination, though some argue that the gap is largely caused by women's choices.

Overview

The most basic way to look at differences in pay between the genders is to look at the median wages of men and women. However, this comparison is of limited usefulness because men and women exhibit very different characteristics for many of the factors that affect pay. For example, men tend to work in fields with higher average pay, and tend to work more hours per week. Because of these differences, in order to determine what effect discrimination has upon the wages of men and women in the workplace the differences in career choices must be accounted for. One must also determine what portion of those differences is caused by career decisions and what portion is caused by employer discrimination in hiring and promotions.

A study commissioned by the United States Department of Labor, concluded that "There are observable differences in the attributes of men and women that account for most of the wage gap. Statistical analysis that includes those variables has produced results that collectively account for between 65.1 and 76.4 percent of a raw gender wage gap of 20.4 percent, and thereby leave an adjusted gender wage gap that is between 4.8 and 7.1 percent." The study also concluded that while in principle more of the wage gap could be explained by differences between the groups, the data that would be needed to account for additional factors were not available. Others have criticized this report as being biased, citing its funding by the Bush administration, and arguing that the conclusions are not supported by the data.

In addition to the dispute over the causes of the portion of the wage gap attributed to measurable known factors such as job position, hours worked, experience, and education, there is disagreement on what factors explain the remaining 5–7%. Some studies assert that the remaining gap is due to discrimination, citing studies that show that replacing a man's name with a woman's name on a resume reduces the salary offered and lowers the employers opinion of the candidate's experience., and studies that showed that women are discriminated against in salary negotiations. While some others, such as the Department of Labor study above conclude otherwise.

Gender pay gap over time

Looking at the gender pay gap over time, the United States Congress Joint Economic Committee showed that as explained inequities decrease, the unexplained pay gap remains unchanged. Similarly, according to economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn and their research into the gender pay gap in the United States, a steady convergence between the wages of women and men is not automatic. They argue that after a considerable rise in women's wages during the 1980s, the gain decreased in the 1990s. A mixed picture of increase and decline characterizes the 2000s. Thus Blau and Kahn assume:

with the evidence suggesting that convergence has slowed in recent years, the possibility arises that the narrowing of the gender pay gap will not continue into the future. Moreover, there is evidence that although discrimination against women in the labor market has declined, some discrimination does still continue to exist.

A wide ranging meta-analysis by Doris Weichselbaumer and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer (2005) of more than 260 published adjusted pay gap studies for over 60 countries has found that, from the 1960s to the 1990s, raw wage differentials worldwide have fallen substantially from around 65 to 30%. The bulk of this decline, however, was due to better labor market endowments of women. The 260 published estimates show that the unexplained component of the gap has not declined over time. Using their own specifications, Weichselbaumer and Winter-Ebmer found that the yearly overall decline of the gender pay gap would amount to a slow 0.17 log points, implying a slow level of convergence between the wages of men and women.

According to economist Alan Manning of the London School of Economics, the process of closing the gender pay gap has slowed substantially and women could earn less than men for the next 150 years because of discrimination and ineffective government policies. A 2011 study by the British CMI revealed that if pay growth continues for female executives at current rates, the gap between the earnings of female and male executives would not be closed until 2109. Women Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) are paid 16% lower on average as compared to their male counterparts.

According to the most recent release by the U.S. Department of Labor (http://www.consad.com/content/reports/Gender%20Wage%20Gap%20Final%20Report.pdf)"Although additional research in this area is clearly needed, this study leads to the unambiguous conclusion that the differences in the compensation of men and women are the result of a multitude of factors and that the raw wage gap should not be used as the basis to justify corrective action. Indeed, there may be nothing to correct. The differences in raw wages may be almost entirely the result of the individual choices being made by both male and female workers." The differences in the opinion of a variety of different sources, economists and think tanks have lead many to believe that corrective action may be necessary in the future if evidence is found that widespread discrimination is happening in the work place among every business, but until hard evidence is provided things ought to stay the same.

Gender pay gap by country

United States

Main article: Gender pay gap in the United States See also: United States womenIn the United States, the gender pay gap is measured as the ratio of female to male median yearly earnings among full-time, year-round (FTYR) workers. The female-to-male earnings ratio was 0.77 in 2009, meaning that, in 2009, female FTYR workers earned 77% as much as male FTYR workers. Women's median yearly earnings relative to men's rose rapidly from 1980 to 1990 (from 60.2% to 71.6%), and less rapidly from 1990 to 2000 (from 71.6% to 73.7%) and from 2000 to 2009 (from 73.7% to 77.0%).

The raw wage gap data shows that a woman would earn roughly 73.7% to 77% of what a man would earn over their lifetime. However, when controllable variables are accounted for, such as job position, total hours worked, number of children, and the frequency at which unpaid leave is taken, in addition to other factors, the U.S. Department of Labor found in 2008 that the gap can be brought down from 23% to between 4.8% and 7.1%.

The gender pay gap has been attributed to differences in personal and workplace characteristics between women and men (education, hours worked, occupation etc.) as well as direct and indirect discrimination in the labor market (gender stereotypes, customer and employer bias etc.).

The estimates for the discriminatory component of the gender pay gap include 5% and 7% for federal jobs, and in at least one study grow as men and women's careers progress. One economist testified to Congress that hundreds of studies have consistently found unexplained pay differences which potentially include discrimination. Another criticized these studies as insufficiently controlled, and opined that men and women would have equal pay if they made the same choices and had the same experience, education, etc. Other studies have found direct evidence of discrimination. For example, fewer replies to identical resumes if sent by women with children than by men with children and more jobs for women when orchestras moved to blind auditions (though the data was mixed on this, since, in normal orchestra interviews, women were preferentially chosen over men for some instruments, such as the flute).

Canada

A study conducted by researchers at the Asper School of Business, University of Manitoba which appears in Supply Chain Management: An International Journal,found that among Canadian supply chain managers, men make an average of $14,296 a year more than women.

The aim of the study was to develop and test hypotheses on determinants of supply chain managers’ salaries. Sex of the manager and size of his or her organization are among the predictors of salary and seven variables were found to be significant predictors of supply chain manager salaries. These variable include: smaller companies tend to pay lower salaries, small business supply chain/logistics managers work longer hours with a professional designation, more experience the greater budgetary responsibility and greater share of compensation coming as a bonus earn higher salaries. Finally, male small business supply chain managers earn more than their female counterparts. The piece includes a discussion of limitations and future research opportunities into the gender salary gap.

It is worth noting that while 90 per cent of respondents who took part in the study had formal education after high school (both men and women), the research suggests that as supply chain managers move up the corporate ladder, they are less likely to be female. It was also found that at the early career stage, larger organizations tended to pay a larger salary, although a gender difference of reported income was not significant at that stage.

Australia

Main article: Gender pay gap in AustraliaIn Australia, the gender pay gap is calculated on the average weekly ordinary time earnings for full-time employees published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The gender pay gap excludes part-time, casual earnings and overtime payments.

Australia has a persistent gender pay gap. Between 1990 and 2009, the gender pay gap remained within a narrow range of between 15 and 17%. In August 2010, the Australian gender pay gap was 16.9%.

Ian Watson of Macquarie University examined the gender pay gap among full-time managers in Australia over the period 2001–2008, and found that between 65 and 90% of this earnings differential could not be explained by a large range of demographic and labor market variables. In fact, a "major part of the earnings gap is simply due to women managers being female." Watson also notes that despite the "characteristics of male and female managers being remarkably similar, their earnings are very different, suggesting that discrimination plays an important role in this outcome." A 2009 report to the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs also found that "simply being a woman is the major contributing factor to the gap in Australia, accounting for 60 per cent of the difference between women’s and men’s earnings, a finding which reflects other Australian research in this area." The second most important factor in explaining the pay gap was industrial segregation.

European Union

At EU level, the gender pay gap is defined as the relative difference in the average gross hourly earnings of women and men within the economy as a whole. Eurostat found a persisting gender pay gap of 17.5% on average in the 27 EU Member States in 2008. There were considerable differences between the Member States, with the pay gap ranging from less than 10% in Italy, Slovenia, Malta, Romania, Belgium, Portugal and Poland to more than 20% in Slovakia, the Netherlands, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Germany, United Kingdom and Greece and more than 25% in Estonia and Austria.

In the U.K., the most significant factors associated with the remaining gender pay gap are part-time work, education, the size of the firm a person is employed in, and occupational segregation (women are under-represented in managerial and high-paying professional occupations.) When comparing full-time roles, men in the UK tend to work slightly longer hours than women in full-time employment. Depending on the age bracket and percentile of hours worked men in full-time employment work between 1.35% and 17.94% more hours than women in full-time employment. Even when taking the differences in hours worked into account a pay gap still exists in the UK and typically increases with age and earnings percentile.

In October 2014 the Equality Act 2010 was augmented to force employers who lose a gender pay gap tribunal to undergo an equal pay audit.

Majority Muslim countries

See also: Female labor force in the Muslim world

Turkey and Saudi Arabia award women the highest annual incomes when adjusted for purchasing power parity in terms of U.S. dollars. Female workers in Turkey are estimated by the World Economic Forum to earn $7,813 while Saudi female workers earn $6,652. Women in Pakistan don't even earn $1,000 for a year's worth of labor ($940) Egyptian, Syrian, Indonesian, Nigerian, and Bangladeshi women earn less, far less for some countries (Syria, Bangladesh, Nigeria), than $3,000 annually. The median annual income for female workers in the United States was $36,931 in 2010.

Impact

Pensions

The European Commission argues that the gender pay gap has far-reaching effects, especially in regard to pensions. Since women's earnings over a lifetime are on average 17.5% (as of 2008) lower than men's, these lower earnings result in lower pensions. As a result, elderly women are more likely to face poverty: 22% of women aged 65 and over are at risk of poverty compared to 16% of men.

Economy

A 2009 report for the Australian Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs argued that in addition to fairness and equity there are also strong economic imperatives for addressing the gender wage gap. The report found that the gender pay gap has a substantial effect on Australia’s economic performance, measured in terms of GDP per capita, and that the value of reducing the gap is substantial. For example, the researchers estimated that a decrease in the gender wage gap of 1 percentage point from 17% to 16% would increase GDP per capita by approximately $260. This equates to around $5,497 million or 0.5 per cent of total GDP, assuming that the Australian population is held constant. The results also indicate that eliminating the whole gender wage gap from 17% (in February 2009) to zero, could be worth around $93 billion or 8.5% of GDP. The researchers also estimate that removing the negative effects associated with the prime determinant of the gap, that is being a woman, could add around $56 billion or 5.1% to total annual GDP.

An October 2012 study by the American Association of University Women found that over the course of a 35 year career, an American woman with a college degree will make about $1.2 million less than a man with the same education. Therefore, closing the pay gap by raising women's wages would have a stimulus effect that would grow the U.S. economy by at least 3% to 4%. In contrast, the $800 billion economic stimulus bill passed by Congress in 2009 is estimated to have grown the GDP by less than 1.5%. Women who are paid more will likely spend that money to support themselves and their families, because so many women live in poverty. Women currently make up 70 percent of Medicaid recipients and 80 percent of welfare recipients. By increasing women's workplace participation from its present rate of 76% to 84%, as it is in Sweden, the U.S. could add 5.1 million women to the workforce, again, 3% to 4% of the size of the U.S. economy.

Economic theories of the gender pay gap

Marginal productivity differences

If workers have different levels of human capital, then pay differences will be a result of differences in their marginal productivity. One could argue that since women are sorted into "less productive" occupations, their lower pay is a result of their lower marginal productivity.

Discrimination

In Neoclassical economics, discrimination is considered inefficient. If an employer were to pay women less than men and less than their marginal productivity, women workers would seek work elsewhere where they could earn higher wages, leaving the employer unable to attract sufficient workers unless wages were raised. Therefore, as employers seek to maximize profits, they will need to pay workers equal to their marginal productivity without differentiating by gender. However, this theory fails to countenance that pay is not regulated by the market per se, but by people, who are not perfectly rational and who will have a number of conscious or subconscious prejudices which can result in discrimination.

Monopsony explanation

In monopsony theory, wage discrimination can be explained by variations in labor mobility constraints between workers. Ransom and Oaxaca (2005) show that women appear to be less pay sensitive than men, and therefore employers take advantage of this and discriminate in their pay for women workers.

Sociological factors

| This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2013) |

Job choices influencing pay gap

For example, in Canada it is shown that women are more likely to take up such employment opportunities, which greatly contrasts with males of the nation. About 20 percent of women between the ages of 25 and 54 will make just under $12 an hour in Canada. The demographic of women who take up jobs paying less than $12 an hour also a proportion that is twice as large as the proportion of men taking on the same type of low-wage work. There still remains the question of why such a trend seems to resonate throughout the developed world. One identified societal factor that has been identified is the influx of women of color and immigrants into the work force. These groups both tend to be subject to lower paying jobs from a statistical perspective.

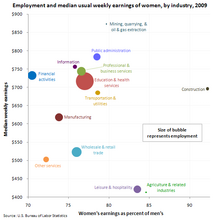

Effect of socialization on gender pay-gaps

Another social factor, which is related to the aforementioned one, is the socialization of women. According to feminist ideology, women are not as encouraged to take on higher education and more challenging jobs, and the male dominated society tends to relegate women to domestically-oriented work. Nonetheless, women continue to do well in higher education when compared to men. Yet studies show the existence of a pay gap even when a woman and man hold the same degree and same experience level. Men are more likely to be in relatively high-paying industries such as mining, construction, or manufacturing and to be represented by a union. Women, in contrast, are more likely to be in clerical jobs and to work in the service industry. These factors explain 53% of the wage gap.

Anti-discrimination legislation

According to the 2008 edition of the Employment Outlook report by the OECD, almost all OECD countries have established laws to combat discrimination on grounds of gender. Legal prohibition of discriminatory behavior, however, can only be effective if it is enforced. The OECD points out that

herein lies a major problem: in all OECD countries, enforcement essentially relies on the victims’ willingness to assert their claims. But many people are not even aware of their legal rights regarding discrimination in the workplace. And even if they are, proving a discrimination claim is intrinsically difficult for the claimant and legal action in courts is a costly process, whose benefits down the road are often small and uncertain. All this discourages victims from lodging complaints.

Moreover, although many OECD countries have put in place specialized anti-discrimination agencies, only in a few of them are these agencies effectively empowered, in the absence of individual complaints, to investigate companies, take actions against employers suspected of operating discriminatory practices, and sanction them when they find evidence of discrimination.

In 2003, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that women in the United States, on average, earned 80% of what men earned in 2000 and workplace discrimination may be one contributing factor. In light of these findings, GAO examined the enforcement of anti-discrimination laws in the private and public sectors. In a 2008 report, GAO focused on the enforcement and outreach efforts of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the Department of Labor (Labor). GAO found that EEOC does not fully monitor gender pay enforcement efforts and that Labor does not monitor enforcement trends and performance outcomes regarding gender pay or other specific areas of discrimination. GAO came to the conclusion that "federal agencies should better monitor their performance in enforcing anti-discrimination laws."

See also

- Equal pay for equal work

- Glass ceiling

- Global Gender Gap Report

- Lowell Mill Girls

- Motherhood penalty

General:

References

- http://www.bluenomics.com/#!data/labour_market/gender_pay_gap/business_economy_b_n_gender_pay_gap/business_economy_b_n_gender_pay_gap_annual_in_%7Cchart/column$countries=germany,greece,united_kingdom,france&sorting=list

- OECD OECD. Retrieved on November 11, 2013.

- European Commission. Gender Pay Gap. Retrieved on August 19, 2011.

- ^ http://social.dol.gov/blog/myth-busting-the-pay-gap/

- ^ http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/07/29/AR2007072900827.html

- AAUW Graduating to a Pay Gap. Retrieved on November 18, 2013.

- ^ "An Analysis of Reasons for the Disparity in Wages Between Men and Women" (PDF). Consad.com. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

- "Gender Pay Gap in the Federal Workforce Narrows as Differences in Occupation, Education, and Experience Diminish" (PDF). U.S. Government Accountability Office. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

- "Wage Gap Myth Exposed - By Feminists | Christina Hoff Sommers". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

- http://amptoons.com/blog/2010/11/26/how-the-consad-report-on-the-wage-gap-masks-sexism-instead-of-measuring-it/

- http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/unofficial-prognosis/2012/09/23/study-shows-gender-bias-in-science-is-real-heres-why-it-matters/

- United States Congress Joint Economic Committee. Graph: Federal Workforce – Gender Pay Gap Unchanged. Retrieved on March 31, 2011.

- Francine D. Blau & Lawrence M. Kahn (2007). The gender pay gap: Have women gone as far as they can? Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 7–23.

- Doris Weichselbaumer and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer (2005). A Meta-Analysis on the International Gender Wage Gap. Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 479–511, doi:10.1111/j.0950-0804.2005.00256.x.

- Manning, Alan (2006). The gender pay gap. Centre for Economic Performance, CentrePiece, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 13–16.

- Woolcock, Nicola. Women will earn the same as men – if they wait 150 years. The Sunday Times, July 28, 2006.

- Goodley, Simon (2011-08-31). "Women executives could wait 98 years for equal pay, says report". The Guardian. London. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

While the salaries of female executives are increasing faster than those of their male counterparts, it will take until 2109 to close the gap if pay grows at current rates, the Chartered Management Institute reveals.

- Chase, Max. "Female CFOs May Be Best Remedy Against Discrimination - CFO Insight". Cfo-insight.com. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

- OECD. OECD Employment Outlook 2008 – Statistical Annex. OECD, Paris, 2008, p. 358.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2009. Current Population Reports, P60–238, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2010, p. 7.

- Institute for Women's Policy Research. The Gender Wage Gap: 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- Kanter, Rosabeth Moss (4 August 2008). Men and Women of the Corporation. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-0-7867-2384-3.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Office of the White House, Council of Economic Advisors, 1998, IV. Discrimination

- Levine, Report for Congress, "The Gender Gap and Pay Equity: Is Comparable Worth the Next Step?", Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, 2003

- ^ "Justice Talking: The Women's Equality Amendment / What Does It Mean and Is It Necessary?". 2007-05-28. Retrieved 2012-03-13.

- ^ United States Congress Joint Economic Committee. Invest in Women, Invest in America: A Comprehensive Review of Women in the U.S. Economy. Washington, DC, December 2010.

- Department of Commerce. Frequently asked questions about pay equity. Retrieved on May 06, 2011.

- ^ National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling. The impact of a sustained gender wage gap on the economy. Report to the Office for Women, Department of Families, Community Services, Housing and Indigenous Affairs, 2009, p. v-vi.

- Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Agency. Pay Equity Statistics. Australian Government, 2010.

- Ian Watson (2010). Decomposing the Gender Pay Gap in the Australian Managerial Labour Market. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 49–79.

- ^ European Commission. The situation in the EU. Retrieved on July 12, 2011.

- Thomson, Victoria (October 2006). "How Much of the Remaining Gender Pay Gap is the Result of Discrimination, and How Much is Due to Individual Choices?" (PDF). International Journal of Urban Labour and Leisure. 7 (2). Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- "Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, 2013 Provisional Results". Ons.gov.uk.

- "A Look At The Gender Pay Gap By Age And Earning Power". Octopus-hr.co.uk.

- Clear Sky Business - Equal pay: rogue firms forced to come clean

- ^ The Global Gender Gap Report 2012, World Economic Forum. By Ricardo Hausmann, Laura D. Tyson and Saadia Zahidi

- "Knowledge Center". Catalyst.org. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

- European Commission. Closing the gender pay gap. March 04, 2011.

- Christianne Corbett and Catherine Hill (October 2012) "Graduating to a Pay Gap: The Earnings of Women and Men One Year after College Graduation" (Washington, DC: American Association of University Women)

- Laura Bassett (October 24, 2012) "Closing The Gender Wage Gap Would Create 'Huge' Economic Stimulus, Economists Say" Huffington Post

- Congress, C. L. (n.d.). Women in the Workforce: Still a Long Way from Equality. Retrieved November 23, 2012, from Canadian Labour Congress.

- Eric Solberg and Teresa Laughlin Industrial and Labor Relations Review Vol. 48, No. 4 (Jul., 1995), pp. 692-708

- The Gender Pay Gap: Have Women Gone as Far as They Can? Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn Academy of Management Perspectives Vol. 21, No. 1 (Feb., 2007), pp. 7-23

- ^ OECD. OECD Employment Outlook – 2008 Edition Summary in English. OECD, Paris, 2008, p. 3–4.

- OECD. OECD Employment Outlook. Chapter 3: The Price of Prejudice: Labour Market Discrimination on the Grounds of Gender and Ethnicity. OECD, Paris, 2008.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Women's Earnings: Federal Agencies Should Better Monitor Their Performance in Enforcing Anti-Discrimination Laws. Retrieved on April 1, 2011.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Report Women's Earnings: Federal Agencies Should Better Monitor Their Performance in Enforcing Anti-Discrimination Laws.

Further reading

- Barry, Richard, "Why Women Earn Less Than Men," Pearson's Magazine, vol. 25, no. 3 (March 1911), pp. 293–300.

- Chase, Max (2 February 2013). Female CFOs May Be Best Remedy Against Discrimination. CFO Insight

- Goldin, Claudia (2008). "Gender Gap". In David R. Henderson (ed.) (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - O'Neill, June Ellenoff (2002). "Comparable Worth". In David R. Henderson (ed.) (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (1st ed.). Library of Economics and Liberty.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor=has generic name (help) OCLC 317650570, 50016270, 163149563 - Wilkinson, Richard; Pickett, Kate (5 March 2009). The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-84614-039-6.

- Mees, Heleen (29. August 29, 2007). "Die Kosten des Gender-Gap" (in German). Project Syndicate. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

External links

- Gender pay gap statistics by Eurostat of the European Commission

- Visualization of the gender pay gap in the UK across different occupations.

- Visualisation of Global gender pay gap

- Assessing the Gender Gap in the Film Industry