This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 160.253.0.7 (talk) at 21:44, 14 December 2006 (→History). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:44, 14 December 2006 by 160.253.0.7 (talk) (→History)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

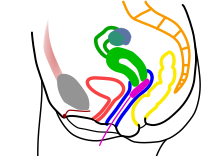

A tampon is a plug of cotton or other absorbent material inserted into a body cavity or wound to absorb fluid. The most common type in daily use (and the topic of the remainder of this article) is a usually disposable plug that is designed to be inserted into a woman's vagina during her menstrual period to absorb the flow of blood. The use of these devices has caused serious health related issues, such as infection and even death in rare cases (see Toxic shock syndrome). In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates tampons as medical devices.

History

There is evidence which suggests that women have been using tampons made of various materials for thousands of years. The tampon with an applicator and string was invented in 1929 and submitted for patent in 1931 by Dr. Matthew Martin, an American from Olney, Maryland. Tampons based on Dr. Martin's design were first sold in the U.S. in 1936.

Design and packaging

Tampons come in various sizes, which are related to their absorbency ratings and packaging.

The shape of all tampons is basically the same; cylindrical. Tampons sold in the United States are made of cotton, rayon, or a blend of the two. Tampons are sold individually wrapped to keep them clean, although they are not sterile. They have a string for ease of removal, and may be packaged inside an applicator to aid insertion.

Tampon applicators may be made of plastic or cardboard, and are similar in design to a syringe. The applicator consists of a bigger tube and a narrower tube. The bigger tube has a smooth surface and a round end for easier insertion. Some applicators have a star shape opening at the round end, others are open ended. The tampon itself rests inside the bigger tube, near the open end. The narrower tube is nested inside the other end of the bigger tube. The open end of the bigger tube is placed and held in the vagina, then the narrower tube is pushed into the bigger tube (typically using a finger) pushing the tampon through and into the vagina. If not inserted at a 45 degree angle it can cause discomfort and make removal difficult.

Digital tampons are tampons sold without applicators; these are simply unwrapped and pushed into the vagina with the fingers (digits).

It is normally not necessary to remove a tampon before urinating or having a bowel movement.

Absorbency ratings

Tampons come in several different absorbency ratings, which are consistent across manufacturers in the U.S.:

- Junior(or light) absorbency: 6 grams and under

- Regular absorbency: 6 to 9 grams

- Super absorbency: 9 to 12 grams

- Super plus absorbency: 12 to 15 grams

- Ultra absorbency: 15 to 18 grams

Toxic shock syndrome

Main article: toxic shock syndromeTampons have been shown to have a connection to toxic shock syndrome (TSS), a rare but sometimes fatal disease caused by bacterial infection. The U.S. FDA suggests the following guidelines for decreasing the risk of contracting TSS when using tampons:

- Follow package directions for insertion

- Choose the lowest absorbency for your flow

- Change your tampon at least every 4 to 8 hours

- Consider alternating pads with tampons

- Avoid tampon usage overnight when sleeping

- Know the warning signs of toxic shock syndrome

- Don't use tampons between periods

Following these guidelines can help to protect a woman from TSS, but if she uses tampons at all, she is still at risk, no matter how careful she is. The only way to avoid this risk is to use other forms of menstrual protection, such as a menstrual cup (worn internally), or sanitary napkin (external).

Environmental impact

Tampons, their applicators, and wrappings are typically used once and then either disposed of in the rubbish, or flushed down a toilet. If flushed down a toilet, they end up in sewage treatment plants where they are filtered out of the effluent. However, note that different countries have different sewage systems and that tampons might cause sewage blockings if flushed down a toilet, especially in small electrical sewage pumps, such as used in toilets on trains, planes and even in some private households. Warning signs in hotels and public toilets can be found in many locations. The warning signs usually include tampons as well as other sanitary articles such as condoms within their list of articles forbidden for flushing down. In these cases, small plastic bags (usually labeled 'sanitary bags') or other trash receptacles are provided for discreet disposal and hygiene. If disposed of in the trash, they may end up in incinerators or landfills (where they can take up to six months to biodegrade). They may not even biodegrade at all. Things get buried and some tampons contain plastics to ease insertion. Packaging and plastic applicators are another concern.

Some tampons are made with genetically modified (GM) cotton. Chlorine bleach is also used in the manufacture of tampons. The bleaching of fibres with chlorine is implicated in dioxin contamination.

Among tampon users, each woman is likely to use about 10,000 tampons during her lifetime.

For the environmentally concerned, a cloth menstrual pad or a menstrual cup may be a preferable option.

Other health concerns

Some of the chemicals used to bleach tampons have been implicated in the formation of dioxin. A study by the FDA done in 1995 says there are not significant amounts of dioxin to pose a health risk; the amount detected ranged from undetectable to 1 part in 3 trillion, which is far less than the normal exposure to dioxin in everyday life. However, the presence of dioxin in a product that enters a major body orifice, where there is more risk of absorption, caused a great deal of concern. Nevertheless, manufacturers insist that bleaching is needed to produce effective products, despite tampons not using bleaching or chemical treatment being available.

Although some say that 100% cotton tampons may be safer than using tampons with a cotton and rayon mix because of there being less dioxin, there is still a risk with all-cotton tampons. All-cotton tampons are generally harder to find and usually cost more than generic tampon brands. Some researchers claim that although switching to a 100% cotton alternative reduces the risk of TSS, it does not remove it entirely. We are also exposed to dioxins in other ways, so eliminating dioxin in tampons will not mean there will be no contact with dioxin in the environment.

Fiber loss along with damage done to the vaginal tissue from fiber has also been a concern, but fiber loss is more likely with all-cotton tampons. Furthermore, as tampons are absorbent and placed within an area such as the vagina this significantly increases risk of bacterial infections.

Alternative choices

Some women choose not to use tampons, due to health and/or environmental concerns. Several alternate ways of absorbing menstrual fluids are available. Women in developing countries are less likely to have these choices (including tampons) available.

Some women may choose not to use tampons because they fear damaging their hymen, regarded as a proof of virginity. In some cultures, the use of tampons by virgins is discouraged because of this.

Disposable

- disposable menstrual pads (sanitary napkins/towels)

- organic tampons

- organic menstrual pads (sanitary napkins/towels)

- softcups menstrual cup

Reusable

- diaphragm as menstrual cup

- cloth menstrual pads

- homemade menstrual pads

- homemade tampons

- Menstrual cup made of silicone, or gum rubber. Non diaphragm.

- Free-flow (layering or instinctive )

- padded panties/period pants/Lunapanties

- sea sponges (used like tampons)

References

- Finley, Harry (1998)(2001). The Museum of Menstruation and Women's Health. Retrieved December 12, 2003 from http://www.mum.org/comtampons.htm

- Khela, Bal (November 26, 1999). The Women's Environmental Network. Retrieved December 13, 2003 from http://www.wen.org.uk/gen_eng/Genetics/tampon1.htm

- Meadows, Michelle (March-April, 2000). Tampon safety: TSS now rare, but women should still take care. FDA Consumer magazine.

- Sanpro. (April 8, 2003). The Women's Environmental Network. Retrieved December 13, 2003 from http://www.wen.org.uk/sanpro/sanpro.htm

- Truths and myths about tampons http://www.snopes.com/toxins/tampon.htm

- Using a Toilet for Tampon Disposal http://publicrestrooms.lifetips.com/cat/61839/public-restroom-feminine-hygiene-guide/index.html