This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Lonewolf BC (talk | contribs) at 21:19, 28 December 2006 (resolve notes from full references). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:19, 28 December 2006 by Lonewolf BC (talk | contribs) (resolve notes from full references)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other people named Robert Gray, see Robert Gray (disambiguation).

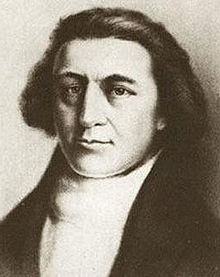

Robert Gray (May 10, 1755 – c. July, 1806) was an American merchant sea-captain and explorer who is known for having completed the first circumnavigation of the world by an American ship, in 1790, and perhaps best known for entering and naming the Columbia River, in 1792. He achieved both in connection with trading voyages to the north Pacific coast of North America, which pioneered the American sea-borne fur trade there.

Earlier life

Gray was born in Tiverton, Rhode Island. Little is known of his early life. He is said to have served in the Continental Navy during the American Revolutionary War, but this is not documented. He is known, however, to have served in the Triangular trade of South Carolina, aboard the Pacific.

Trading Voyages of 1787–1793

First Voyage to Pacific Northwest Coast 1787-1790

In 1787, Robert Gray and Captain John Kendrick left Boston in two ships, to trade along the north Pacific coast. They were sent by Boston merchants including Charles Bulfinch. Bulfinch and the other financial backers came up with the idea of trading pelts from the northwest coast of North America and taking them directly to China after Bulfinch had read about Captain Cook’s success doing the same. Bulfinch had read Cook’s Journals that were published in 1784 that in part discussed his success selling sea otter pelts in Canton, and thus the American merchants thought they could replicate that success. Prior to this, other America traders such as Robert Morris had sent ships to trade with China, notably the Empress of China in 1784, but had problems with finding specie acceptable to the Chinese. Cook’s trading and Bulfinch’s learning of this solved the problem of specie so that profitable triangular trading could occur between the New England sea merchants and the China market.

During their trading up and down the coastlines of what is now British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California the two explored many bays and inland waters, including an inland sea north of Nootka Sound. Gray then encountered Captain Mears of England and relayed this information to him, which lead to the British sending out additional ships to explore the coast under the command of Captain George Vancouver. And in 1788 Gray had attempted to enter a large river, but was unable to due to the tides, this river being the Columbia River. At the outset of the voyage, Gray captained the Lady Washington and Kendrick captained the Columbia Rediviva, but the captains swapped vessels during the voyage, putting Gray in command of the Columbia. After the switch Kendrick then stayed on the coast trading for pelts and furs, while Gray sailed their existing cargo of pelts to China, stopping off at the Sandwich Islands en route. Gray arrived in Canton, China in early 1790. In China he traded his cargo for large amounts of tea. Gray then continued on west, sailing around the Cape of Good Hope and arriving back in Boston on August 10th, 1790. As such, the Columbia became the first American vessel to circumnavigate the globe.

Also on this voyage Kendrick and Gray were instructed to purchase as much land as they could from the Native Americans. Kendrick did so on at least two occasions, including on August 5, 1791 where he purchased 18 square miles near 49’ 50” from a native tribe. This purchase occurring while Gray had completed his voyage and since returned.

The success in profits realized by this voyage had two main effects, with the most immediate having Gray return to the Northwest only six weeks after returning. The second effect was that it lead to other New England sea merchants sending out their own vessels to that part of the world to take part in this new trade opportunity. This included Gray’s first mate Joseph Ingraham being sent out by other merchants on the ship hope in September 1790. Within a few years many Yankee merchants were involved in the continuous trade of pelts to China and by 1801 sixteen vessels were engaged in this triangular route. These activities encroached upon other nation’s territorial claims, notably Spain and Russia to the south and north of the disputed Oregon Country. However, these activities help to strengthen the United States claims in the coming years to much of the Oregon Country while restricting Spain’s claims to California and Russia’s claims to Alaska.

Circumnavigation

Gray crossed the Pacific to China in 1790, and traded his furs for tea and other Chinese goods. He then carried on westerly, through the Indian Ocean, around the Cape of Good Hope, and across the Atlantic, back to Boston. His return there, in late 1790, completed the first circumnavigation of the world by an American vessel.

Second Voyage to Pacific Northwest Coast, 1790-1793

On September 28, 1790 Gray set sail again with the Columbia to the northwest coast, heading for Nootka Sound. On this voyage Gray was sailing under papers of the United States signed by President George Washington, though he was still a private merchant. Gray and the Columbia arrived back on June 5, 1791, sailing as far north as the Queen Charlotte Islands during this voyage. There the traders wintered at a stockade they built and named Fort Defiance. During this winter the crew built a 30 ton sloop that Gray then named Adventurer that was launched that spring with Gray’s first mate Robert Haswell in charge.

Once April came Gray and the Columbia sailed south while the Adventurer sailed north. While traveling south the Columbia encountered Vancouver’s expedition and the two captains met and discussed the geography of the coastlines. Gray told Vancouver about the large river he had attempted to enter in 1788, but Vancouver doubted there was a large river at that latitude. So Gray continued south, leaving the Strait of Juan de Fuca on April 30, 1792 trading for more pelts as the ship sailed. On May 7, the ship entered what is now Gray’s Harbor, Washington where Gray named the bay Bullfinch Harbor. The name was later changed to Gray’s Harbor. Then on May 11, 1792, he entered and named the Columbia River, which would form part of the basis for U.S. territorial claims to Oregon Country. Gray then finished filling his cargo hold with pelts and set sail for China. Again in Canton, Gray traded his cargo for tea and returned to Boston.

Later Life

On February 3, 1794 Gray was married to Martha Gray in Boston by the Reverend John Eliott. Gray then died in 1806 while sailing near Charleston, South Carolina. He left behind Martha and four daughters, who later petitioned Congress for a government pension based on his voyages and a claim that he was a naval officer for the United States during the Revolutionary War.

Legacy

Gray's discoveries on the lower Columbia, and elsewhere along the same coast, which he did not publish, attracted little attention and gained him no renoun at the time. After getting back to Boston in 1793, he returned to his former obscurity. However, his priority in entering of the Columbia estuary was later used as a basis for American territorial claims to the Oregon Country, known also, in the terminology of the rival British claim, as the Columbia District.

Namesakes

- Grays Harbor (map) and Grays Harbor County, in Washington State

- Grays Bay (Washington), on the north shore of the Columbia River estuary (map)

- Grays Point (Washington), at the west of Grays Bay (map)

- Grays River (Washington), a tributary of the Columbia River, flowing into Grays Bay (map)

- Grays River, Washington, a small, unincorporated rural village on the river of the same name (map)

- Robert Gray Avenue in Tiverton, Rhode Island

See also

Notes

References

- Kushner, Howard I. (1975). Conflict on the Northwest Coast: American-Russian Rivalry in the Pacific Northwest, 1790-1867. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-8371-7873-8.

- Lockley, Fred (1929). Oregon Trail Blazers. The Knickerbocker Press.