The Royal Alcázar of Madrid (Spanish: Real Alcázar de Madrid) was a fortress located at the site of today's Royal Palace of Madrid, Madrid, Spain. The structure was originally built in the second half of the ninth century by the Muslims, then extended and enlarged over the centuries, particularly after 1560. It was at this time that the fortress was converted into a royal palace, and Madrid became the capital of the Spanish Empire. Despite being a palace, the great building kept its original Arabic title of Alcázar (English: "castle").

The first extension to the building was commissioned by King Charles I (Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor) and completed in 1537. Its exterior was constructed by the architect Juan Gómez de Mora in 1636 on a commission from King Philip IV.

As famous for its artistic treasures as it is for its unusual architecture, it was the residence of the Spanish royal family and home of the court, until its destruction by fire during the reign of King Philip V (the first Bourbon king), on Christmas Eve 1734. Many artistic treasures were lost, including over 500 paintings. Other works, such as the painting Las Meninas by Velázquez, were saved.

History

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Royal Alcázar of Madrid" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (September 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Origins

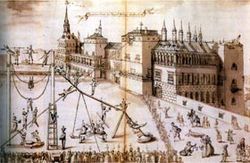

There is much documentation (numerous texts, engravings, plans, paintings and models) on the building layout and exterior between 1530 and 1734, when they were destroyed in a fire. However, images of the building's interior and references to its history are scarce.

The first drawing of the Alcázar was done by Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen in 1534, three decades before Madrid was named as the capital of Spain. The drawing shows a castle divided into two main parts, which may correspond, at least partially, to the structure of the Muslim fortress on which it was built.

This original fortress was erected by the Umayyad amir Muhammad I of Córdoba (852–886) between 860 and 880. The building was the central nucleus of the Islamic citadel of Mayrit, a walled district approximately 4 ha (9.9 acres) in size, incorporating not only the castle, but also a mosque and the home of the governor (or emir).

Its steep location near the Altos de Rebeque and overlooking the path of the River Manzanares below was of great strategic importance, being a key factor in the defence of Toledo from frequent Christian incursions into the lands of al-Andalus. This structure probably followed the progression of similar military constructions in the area—an observation point developed into a small fort—although there is currently a lack of evidence as the place was later quarried for building material by Christians.

After the conquest of Madrid in 1083 by Alfonso VI of León and Castile, the King needed a bigger fortress in order to accommodate his royal court. A new fortress was built to the north of the first walled enclosure — therefore, the Islamic fortress was never located under the royal palace.

Over the course of time, the old castle was extended, keeping the original structure within. This is evident from seventeenth century engravings and paintings, where medieval-styled semi-circular turrets can be seen on the western side by the Manzanares, in contrast to the architecture of the southern façade.

The House of Trastámara

The Trastámara dynasty turned the Alcázar into its temporary residence, and by the end of the fifteenth century it was one of the main fortresses in the Crown of Castile, as well as the seat of the royal court. In keeping with its new function, the castle incorporated the word royal into its name, indicating its exclusive use by the Castilian monarchy.

King Henry III of Castile instigated the construction of different towers which changed the look of the building, giving it a more palatial feel. His son, John II, built the Royal Chapel and added a new room, known as the Sala Rica (the Room of Riches) for its lavish decoration. These two new elements, alongside the eastern façade, are thought to have increased the surface area of the old castle by approximately 20 percent.

Henry IV of Castile was one of the kings who spent the most time at the Alcázar, with one of his daughters, Joanna la Beltraneja, being born there on 28 February 1462. In 1476, Juana la Beltraneja's followers were besieged in the Alcázar because of the War of the Castilian Succession with Queen Isabella I over the throne. The area suffered considerable damage during the siege.

Charles V

The Royal Alcázar of Madrid once again suffered serious damage during the Revolt of the Comuneros, which occurred from 1520 to 1522, under the reign of Charles I. Considering the state of the building, Charles I decided to extend it; this is considered to be the first important building work in the history of the Alcázar. The redesign was probably carried out alongside the Emperor's wish to establish the court in the city of Madrid, something which did not happen until the reign of Philip II. Luis Cabrera de Córdoba (16th century), mentioned Charles in the following document, "The Catholic King Philip II, considering the city of Toledo unsuitable, respected the wish of his father, the Emperor Charles V to have the Court in the city of Madrid, establishing in Madrid its royal seat and the government of its monarchy."

From this perspective, one can understand the efforts of Charles V to provide the city with a royal residence - the priority of a modern state - or at least, to what it was used to before his arrival in Castile. Instead of demolishing the uncomfortable and old-fashioned medieval castle (a decision thought to be too radical), the Emperor decided to use it as the basis for the construction of a palace. The new construction bore the name of the original fortress, the Royal Alcázar of Madrid, despite having lost its military function centuries earlier.

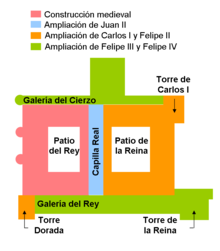

Construction started in 1537, under the direction of the architects Luis de Vega and Alonso de Covarrubias, who renovated the old buildings around the King's Courtyard (Patio del Rey) in the medieval castle. The most valuable contribution, however, was the construction of the newly designed Queen's rooms, spread around the Queen's Courtyard (Patio de la Reina). The so-called Tower of Charles V was built in one of the corners of the northern façades, which now overlooks the Sabatini Gardens. These new additions are believed to have doubled the original footprint of the building.

The project was dominated by unmistakable Renaissance features, visible in the main staircase and both the King's and Queen's Courtyards; adorned with archways and supported by columns, allowing light into the building. The extension by Charles V was the first important work carried out in the Alcázar, and was followed by numerous refurbishments and redesigns which were carried out almost continuously until the building's destruction in the 18th century.

Philip II

Philip II, as prince of Asturias, had shown great interest in the works brought about by his father, the Emperor Charles V, and as king, continued them. He accomplished the transformation of the building into a palace, especially from 1561, when he decided to establish the court permanently in Madrid.

The monarch ordered the refurbishment of his chambers as well as other rooms, and put special effort into their decoration, using tailors, glaziers, carpenters, painters, sculptors and other artisans and artists. Many of these tradesmen came from the Netherlands, Italy and France. The works, which lasted from 1561 until 1598, were initially managed by Gaspar de la Vega.

The Golden Tower (la Torre Dorada), whose construction was the most important in this time, was supervised by the architect Juan Bautista de Toledo. This vast tower dominated the south-western edge of the Alcázar and was crowned with a slate spire. The tower's design was reminiscent of the corner towers of the monastery of El Escorial, which was also under construction at the same time.

Philip II oversaw the Royal Alcázar of Madrid's complete conversion to a royal palace. The interior section between the two original towers of the southern façade took on a ceremonial function, while the northern wing was used as the service area. The western area was reserved for the King's chambers, with the Queen's chambers to the east. The areas were separated by two large courtyards, in keeping with the structure designed by de Covarrubias. This layout of the areas for different uses was maintained until the fire of 1734.

The construction of the Royal Armoury was also the work of Philip II. Demolished in 1894, in its location is now the crypt of Almudena Cathedral.

Philip III, Philip IV and Charles II

By the end of Philip II's reign, and despite many improvements, the Royal Alcázar still had an incongruous appearance. Its main façade, on the south, retained medieval elements which did not match the alterations made by the monarch. The clash of styles was very noticeable with respect to the Golden Tower (incorporated by the King) and the two other medieval cuboid towers that took away light from the development.

Upon taking the throne, Philip III, son of Philip II, set about making the southern façade his main project. The work, entrusted to the architect Francisco de Mora, involved blending the southern façade with the architectural characteristics of the Golden Tower, as well as redesigning the Queen's rooms.

However, the work to the façade was eventually completed by Juan Gómez de Mora, the preceding architect's nephew, who introduced important innovations to his uncle's design, following the usual Baroque style of the time. The new design, started in 1610 and finished in 1636 during the reign of Philip IV, would survive until the fire of 1734. The enclosure of the exterior plaza was also completed under de Mora.

The development gained brightness and balance, thanks to a series of windows and columns from the two symmetrical towers (as illustrated below). The other façades were also remodelled, with the exception of the western side that retained the look of the old medieval castle.

Philip IV gave the building a more harmonious appearance, despite his indifference towards it. The monarch refused to live in the Alcázar and ordered the construction of a second palace, the Buen Retiro Palace, which today also no longer exists. Walls were erected, to the east of the city, on the grounds which are now home to the Retiro Park.

The project, started by Philip III and finished by Philip IV continued throughout the reign of Charles II, in the form of minor alterations and renovations. The Queen's Tower, located on the south-eastern side, was finished with a slate spire in keeping with the design of the Golden Tower on the other side, built during the reign of Philip II. The plaza built at the foot of the southern façade also incorporated different rooms and galleries.

Philip V

Philip V was proclaimed king of Spain on 24 November 1700, in a ceremony performed in the southern plaza of the palace – the plaza is now the site of the Armoury Plaza. The austere Royal Alcázar was in complete opposition with the French taste he was more familiar with in Versailles, hence his refurbishments' focus on the interior of the palace.

The main rooms were redecorated in the style of French palaces. Queen Maria Luisa of Savoy was in charge of the work, assisted by her lady in waiting, Marie Anne de La Trémoille, princess of Ursins.

The redesign of the Alcázar's interior was initially the responsibility of the architect Teodoro Ardemans, who was later replaced by René Carlier.

The fire of 1734

On 24 December 1734, with the Court having moved to the El Pardo Palace, a fire broke out at the Royal Alcázar of Madrid. Thought to have started in a room of the court artist Jean Ranc, the fire spread quickly and uncontrollably. It raged for four days and was so intense that some silver objects were melted by the heat and other metal objects, along with precious stones, had to be discarded.

According to Félix de Salabert, Marquis of Torrecillas, the first alarm was raised at approximately 15 minutes past midnight by one of the guards on duty. The festive nature of the day meant that the warning was ignored at first, since people were on their way to matins (night prayer service). The first to attempt help (as much in extinguishing the fire as in trying to rescue people and valuables) were the monks from the monastery of San Gil.

Initially, the doors of the Alcázar were kept closed for fear of looting. This meant that occupants had little time to evacuate. It was an enormous effort to salvage the religious objects kept in the Royal Chapel, as well as cash and jewels belonging to the royal family (a chest full of coins was thrown from a window). The collection of jewels included the Pilgrim Pearl and the El Estanque diamond.

The rescue of several paintings on the second floor of the Alcázar was abandoned due to the difficulties posed by their size and location at various heights and in different rooms. Some paintings were fixed to the walls, so a large number of those kept in the building (including La Expulsión de los moriscos by Velázquez) were lost. Others such as Las Meninas (also by Velázquez) were saved by being removed from their frames and thrown from the windows. Fortunately, part of the art collection had previously been moved to the Buen Retiro Palace to protect them during the building work to the Royal Alcázar, which saved them from destruction.

After the fire was extinguished, the building was reduced to rubble. The walls which remained were demolished, due to the extent of the damage. In 1738, four years after the fire, Philip V ordered the construction of the current Royal Palace of Madrid, which spanned three decades. The new building was used as a residence for the first time in 1764 by Charles III.

Characteristics

Despite the efforts to give the building a more harmonious design, the modifications, extensions and refurbishments carried out over the centuries did not achieve this goal. French and Italian visitors criticised the irregular façades and deemed the building's interior labyrinth-like. Many of the private rooms were dark and had no windows for ventilation, something much sought-after in the hot climate of Madrid.

The main area of asymmetry was the western façade, which, being situated on the edge of the ravine of the Manzanares Valley was the least visible from the urban area of Madrid. However, at the same time, it was the first view seen by visitors coming into the city from the Segovia Bridge.

It was this façade which underwent the fewest redesigns and as a consequence retained the most medieval character of the building. It was made entirely of stone, with four turrets, although several windows bigger than those in the old fortress had been built. The four turrets were finished with conical slate spires, similar to those on the Alcázar of Segovia, which reduced the military feel of the building.

The remaining façades were built from red brick and granite (from Toledo), which gave the building the characteristic colouring of Madrid's traditional architecture. These materials were abundant in the influential area of the city as clay is plentiful on the banks of the Manzanares and granite in the nearby Sierra de Guadarrama.

The main entrance was on the southern façade, which proved especially problematic in the redesign of the building, due to being dominated by two large square spaces, built in medieval times. Both of these interrupted the longitudinal line of the façade which linked the Golden Tower (built under the reign of Philip II) with the Queen's Tower (built during the refurbishments under Philip III and Philip IV).

With the design of Juan Gómez de Mora, the towers were hidden, giving more balance to the building as a whole. This can be seen in the 1704 drawing by Filippo Pallota. This architect also integrated the appearance of the Golden Tower and the Queen's Tower by adding a pyramid-shaped spire to the Queen's Tower, identical to that of the Golden Tower.

The Royal Alcázar of Madrid was based on a rectangular plan. Its interior, divided by two large courtyards, was organised asymmetrically (see image 3). The King's Courtyard, situated in the western part of what was the medieval castle, was smaller than the Queen's Courtyard on the opposite side. This courtyard divided the rooms built during the reign of Charles I. The Royal Chapel was erected between the courtyards under the orders of King John II of the Trastámara dynasty. For many years, the courtyards were open to the public and markets were held there, selling a variety of goods.

The Royal Alcázar art gallery

The Royal Alcázar held a huge art collection; it is estimated that at the time of the fire, there were close to 2,000 paintings (both originals and reproductions), of which some 500 were lost. The approximately 1,000 paintings which were rescued were kept in several buildings after the event, amongst them the San Gil Convent, the Royal Armoury and the homes of the Archbishop of Toledo and the Marquis of Bedmar. A large part of the art collection had already been moved to the Buen Retiro Palace during the building work carried out on the Alcázar, which saved them from the fire.

One of the major works lost was La Expulsión de los moriscos, by Diego Velázquez. This painting won a competition in 1627, the prize being the post of usher chamber. This was a decisive step in his career and allowed him to take his first trip to Italy. He also painted an equestrian portrait of King Philip IV, as well as three of the four paintings from the mythological series (Apollo, Adonis & Venus, and Psyche & Cupid), of which only one was saved, Mercury & Argos.

Several of the works lost in the fire were by Peter Paul Rubens. Among these was an equestrian portrait of Philip IV specially commissioned by the King, which had pride of place in the Room of Mirrors (Salón de los Espejos), opposite the famous Titian portrait, Charles V at Muhlberg.

The Uffizi Gallery in Florence is home to a good reproduction of the Rubens portrait. Also lost in the fire was another Rubens painting, El rapto de las Sabinas, and the twenty pieces of art that adorned the walls of the Octagonal Room (Pieza Ochavada).

Among the Titian pieces which were destroyed was the series the Eleven Caesars, which was kept in the Great Room (Salón Grande), famous today for its reproductions and a series of engravings by Aegidius Sadeler II. Also lost were two of the four Furias series which were in the Room of Mirrors (the other two are now in the Museo del Prado in Madrid). As well as these works, an invaluable collection of work by artists such as (according to the inventories) Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese, Jusepe de Ribera, Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Alonso Sánchez Coello, Anthony van Dyck, El Greco, Annibale Carracci, Leonardo da Vinci, Guido Reni, Raphael, Jacopo Bassano, Correggio, and many others.

Among remaining sculptures are the bronze Medici lions from the Room of Mirrors, of which four now are present in the throne room of the current Royal Palace of Madrid, and the remaining eight in the Museo del Prado.

Further developments

The developments made throughout the history of the Royal Alcázar of Madrid affected not just the building itself, but also the surrounding area, with a series of developments within its grounds. The Royal Stables were built to the south of the Alcázar, incorporating the rooms of the Royal Armoury. To the north and west of the Alcázar lay the Picadero plaza and the Gardens (or Orchard) of the Prioress, which connected the palace with the Royal Monastery of the Incarnation. To the east, the House Treasury was built.

The House Treasury

This name was given to a building complex designed for various services, which included two main sites: the Houses of Offices and the new kitchens.

The work, beginning in 1568 under the reign of Philip II, was initially designed to be an independent construction, but the building became an annex to the Alcázar so as to enable direct communication between them.

In the seventeenth century, a passageway was built which connected the House Treasury with the Royal Monastery of the Incarnation, so that the royals could access the monastery directly from the palace.

The House Treasury became home to the Royal Library (later the National Library) under the initiative of King Philip V. The complex, which survived the fire of 1734, was demolished by order of King Joseph Bonaparte who intended to create a large plaza next to the eastern façade of the Royal Palace of Madrid.

The basements, floors and other walls of the building were discovered in the twentieth century during the 1996 redesign of the Plaza de Oriente by the mayor José María Álvarez del Manzano. Despite their historic importance, the remains were destroyed.

The Royal Stables and Royal Armoury

In 1553, King Philip II decided to create a complex to house the Royal Stables in the area surrounding the Alcázar. The complex was built opposite the southern plaza of the palace, the area which is now home to the crypt of the Almudena Cathedral. The project, managed by the builder Gaspar de Vega, lasted from 1556 until 1564 with later modifications to the complex.

The building was rectangular with a long central area 80 by 10 metres (262 ft × 33 ft), divided into two series of columns (37 in total), which supported a vaulted roof. The troughs were on either side of the corridor. The Royal Stables had three main facades: the main façade with its granite arch, overlooking the Royal Alcázar, another on the side of the central corridor, and the last, open to the palace plaza, facing south. This last side was known as the Armoury Arch.

In 1563, the King ordered the installation of the Royal Armoury on the upper level. Until now, the Armoury had been located in the city of Valladolid. This meant an alteration to the initial design, according to which the upper level was reserved for the stablehands' quarters. In 1567, sloping slate roofs were added and the complex was finally built up to three storeys. The building was demolished in 1894 to make way for the construction of the neo-Romanesque crypt of the Almudena Cathedral.

The Gardens of the Prioress

The Gardens (or Orchard) of the Prioress were the result of a redesign of the grounds to the north and west of the Royal Alcázar, at the start of the seventeenth century. This was the result of the foundation of the Royal Monastery of the Incarnation in 1611.

The gardens were managed by the monastery and were situated on the site where today the Cabo Noval Gardens can be found, within the Plaza de Oriente.

In 1809 and 1810, King Joseph Bonaparte ordered the seizure and destruction of the Orchard of the Prioress, as well as the demolition of the buildings in the surrounding area. His aim was to create a monumental plaza to the east of the Royal Palace but this project did not materialise until the reign of Isabella II, when the layout of the Plaza de Oriente was finally completed.

See also

References

- López-Rey, José (1999). Velázquez: Catalogue Raisonné. Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-8277-1.

- ^ Viso, E.E., 2014, The Royal Palace Madrid, Madrid: Patrimonio Nacional, ISBN 9782758005896

- González, Juan B. (2007). España estratégica: Guerra y diplomacia en la historia de España. Madrid: Sílex ediciones. p. 222. ISBN 9788477371830.

- Sancho, J.L., 2014, Guide Palacio Real de Madrid, Madrid: Patrimonio Nacional, ISBN 9788471202949

- "León - Colección - Museo Nacional del Prado". www.museodelprado.es. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Fernando Brambalia. "View of part of the Royal Palace taken from la Cuesta de la Vega". Spain Ministry of Economy and Public Administrations. Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

External links

- Información del Real Alcázar de Madrid en www.madridhistorico.com

- Historia del Real Alcázar de Madrid y reconstrucción virtual Archived 28 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine en www.museoimaginado.com

- Vídeo virtual sobre el Alcázar — Otro vídeo virtual

- [REDACTED] Media from Commons

| Demolished landmarks in Madrid | |

|---|---|

| Founded before the Habsburgs | |

| Built during the Habsburgs |

|

| Built during the Early Bourbons | |

| Built from the 19th century | |

| City Walls and Gate Walls | |

| Related | |

| Other | |

40°25′05″N 3°42′51″W / 40.41806°N 3.71417°W / 40.41806; -3.71417

Categories:- 9th-century fortifications

- Buildings and structures completed in 1537

- Buildings and structures completed in 1636

- Palaces in Madrid

- Royal residences in Spain

- Alcazars and Alcazabas in Spain

- Demolished buildings and structures in Madrid

- Castles in the Community of Madrid

- Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

- Philip II of Spain

- Herrerian architecture

- 1537 establishments in Spain

- Former castles in Spain

- Former military installations

- Former palaces in Spain

- Buildings and structures demolished in 1734

- 1734 disestablishments in Europe

- 1730s disestablishments in Spain

- Former buildings and structures in Madrid

- Burned buildings and structures in Spain

- Revolt of the Comuneros