| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name Poly(1-methylethylene) | |

| Other names

Polypropylene; Polypropene; Polipropene 25 ; Propene polymers; Propylene polymers; 1-Propene; n | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.117.813 |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | (C3H6)n |

| Density | 0.855 g/cm, amorphous 0.946 g/cm, crystalline |

| Melting point | 130 to 171 °C (266 to 340 °F; 403 to 444 K) |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C , 100 kPa).

| |

Polypropylene (PP), also known as polypropene, is a thermoplastic polymer used in a wide variety of applications. It is produced via chain-growth polymerization from the monomer propylene.

Polypropylene belongs to the group of polyolefins and is partially crystalline and non-polar. Its properties are similar to polyethylene, but it is slightly harder and more heat-resistant. It is a white, mechanically rugged material and has a high chemical resistance.

Polypropylene is the second-most widely produced commodity plastic (after polyethylene).

History

Phillips Petroleum chemists J. Paul Hogan and Robert Banks first demonstrated the polymerization of propylene in 1951. The stereoselective polymerization to the isotactic was discovered by Giulio Natta and Karl Rehn in March 1954. This pioneering discovery led to large-scale commercial production of isotactic polypropylene by the Italian firm Montecatini from 1957 onwards. Syndiotactic polypropylene was also first synthesized by Natta. Interest in polypropylene development is ongoing to the present. For example, making polypropylene from bio-based resources is a topic of interest in the 21st century.

Chemical and physical properties

Polypropylene is in little aspects similar to polyethylene, especially in solution behavior and electrical properties. The methyl group improves mechanical properties and thermal resistance, although the chemical resistance decreases. The properties of polypropylene depend on the molecular weight and molecular weight distribution, crystallinity, type and proportion of comonomer (if used) and the isotacticity. In isotactic polypropylene, for example, the methyl groups are oriented on one side of the carbon backbone. This arrangement creates a greater degree of crystallinity and results in a stiffer material that is more resistant to creep than both atactic polypropylene and polyethylene.

Mechanical properties

The density of PP is between 0.895 and 0.93 g/cm. Therefore, PP is the commodity plastic with the lowest density. With lower density, moldings parts with lower weight and more parts of a certain mass of plastic can be produced. Unlike polyethylene, crystalline and amorphous regions differ only slightly in their density. However, the density of polyethylene can significantly change with fillers.

The Young's modulus of PP is between 1300 and 1800 N/mm².

Polypropylene is normally tough and flexible, especially when copolymerized with ethylene. This allows polypropylene to be used as an engineering plastic, competing with materials such as acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS). Polypropylene is reasonably economical.

Polypropylene has good resistance to fatigue.

Thermal properties

The melting point of polypropylene occurs in a range, so the melting point is determined by finding the highest temperature of a differential scanning calorimetry chart. Perfectly isotactic PP has a melting point of 171 °C (340 °F). Commercial isotactic PP has a melting point that ranges from 160 to 166 °C (320 to 331 °F), depending on atactic material and crystallinity. Syndiotactic PP with a crystallinity of 30% has a melting point of 130 °C (266 °F). Below 0 °C, PP becomes brittle.

The thermal expansion of PP is significant, but somewhat less than that of polyethylene.

Chemical properties

Propylene molecules prefer to join together "head-to-tail", giving a chain with methyl groups on every other carbon, but some randomness occurs.

Polypropylene at room temperature is resistant to fats and almost all organic solvents, apart from strong oxidants. Non-oxidizing acids and bases can be stored in containers made of PP. At elevated temperature, PP can be dissolved in nonpolar solvents such as xylene, tetralin and decalin. Due to the tertiary carbon atom, PP is chemically less resistant than PE (see Markovnikov rule).

Most commercial polypropylene is isotactic and has an intermediate level of crystallinity between that of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE). Isotactic & atactic polypropylene is soluble in p-xylene at 140 °C. Isotactic precipitates when the solution is cooled to 25 °C and atactic portion remains soluble in p-xylene.

The melt flow rate (MFR) or melt flow index (MFI) is a measure of molecular weight of polypropylene. The measure helps to determine how easily the molten raw material will flow during processing. Polypropylene with higher MFR will fill the plastic mold more easily during the injection or blow-molding production process. As the melt flow increases, however, some physical properties, like impact strength, will decrease.

There are three general types of polypropylene: homopolymer, random copolymer, and block copolymer. The comonomer is typically used with ethylene. Ethylene-propylene rubber or EPDM added to polypropylene homopolymer increases its low temperature impact strength. Randomly polymerized ethylene monomer added to polypropylene homopolymer decreases the polymer crystallinity, lowers the melting point and makes the polymer more transparent.

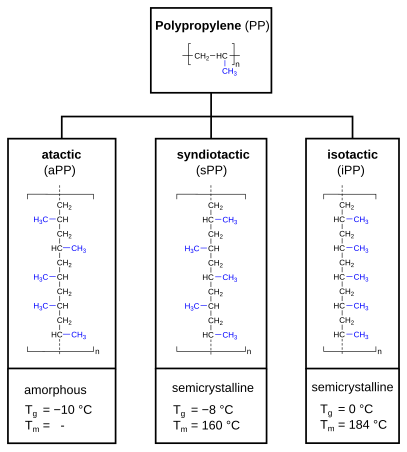

Molecular structure – tacticity

Polypropylene can be categorized as atactic polypropylene (aPP), syndiotactic polypropylene (sPP) and isotactic polypropylene (iPP). In case of atactic polypropylene, the methyl group (-CH3) is randomly aligned, alternating (alternating) for syndiotactic polypropylene and evenly for isotactic polypropylene. This has an impact on the crystallinity (amorphous or semi-crystalline) and the thermal properties (expressed as glass transition point Tg and melting point Tm).

The term tacticity describes for polypropylene how the methyl group is oriented in the polymer chain. Commercial polypropylene is usually isotactic. This article therefore always refers to isotactic polypropylene, unless stated otherwise. The tacticity is usually indicated in percent, using the isotactic index (according to DIN 16774). The index is measured by determining the fraction of the polymer insoluble in boiling heptane. Commercially available polypropylenes usually have an isotactic index between 85 and 95%. The tacticity effects the polymer's physical properties. As the methyl group is in isotactic propylene consistently located at the same side, it forces the macromolecule in a helical shape, as also found in starch. An isotactic structure leads to a semi-crystalline polymer. The higher the isotonicity(the isotactic fraction), the greater the crystallinity, and thus also the softening point, rigidity, e-modulus and hardness.

Atactic polypropylene, on the other hand, lacks any regularity, which prevents it from crystallization, thereby creating an amorphous material.

Crystal structure of polypropylene

Isotactic polypropylene has a high degree of crystallinity, in industrial products 30–60%. Syndiotactic polypropylene is slightly less crystalline, atactic PP is amorphous (not crystalline).

Isotactic polypropylene (iPP)

Is polypropylene can exist in various crystalline modifications which differ by the molecular arrangement of the polymer chains. The crystalline modifications are categorized into the α-, β- and γ-modification as well as mesomorphic (smectic) forms. The α-modifications is predominant in iPP. Such crystals are built from lamellae in the form of folded chains. A characteristic anomaly is that the lame are arranged in the so-called "cross-hatched" structure. The melting point of α-crystalline regions is given as 185 to 220 °C, the density as 0.936 to 0.946 g·cm. The β-modification is in comparison somewhat less ordered, as a result of which it forms faster and has a lower melting point of 170 to 200 °C. The formation of the β-modification can be promoted by nucleating agents, suitable temperatures and shear stress. The γ-modification is hardly formed under the conditions used in industry and is poorly understood. The mesomorphic modification, however, occurs often in industrial processing, since the plastic is usually cooled quickly. The degree of order of the mesomorphic phase ranges between the crystalline and the amorphous phase, its density is with 0.916 g·cm comparatively. The mesomorphic phase is considered as cause for the transparency in rapidly cooled films (due to low order and small crystallites).

Syndiotactic polypropylene (sPP)

Syndiotactic polypropylene was discovered much later than isotactic PP and could only be prepared by using metallocene catalysts. Syndiotactic PP has a lower melting point, with 161 to 186 °C, depending on the degree of tacticity.

Atactic polypropylene (aPP)

Atactic polypropylene is amorphous and has therefore no crystal structure. Due to its lack of crystallinity, it is readily soluble even at moderate temperatures, which allows to separate it as by-product from isotactic polypropylene by extraction. However, the aPP obtained this way is not completely amorphous but can still contain 15% crystalline parts. Atactic polypropylene can also be produced selectively using metallocene catalysts, atactic polypropylene produced this way has a considerably higher molecular weight.

Atactic polypropylene has lower density, melting point and softening temperature than the crystalline types and is tacky and rubber-like at room temperature. It is a colorless, cloudy material and can be used between −15 and +120 °C. Atactic polypropylene is used as a sealant, as an insulating material for automobiles and as an additive to bitumen.

Copolymers

Polypropylene copolymers are in use as well. A particularly important one is polypropylene random copolymer (PPR or PP-R), a random copolymer with polyethylene used for plastic pipework.

PP-RCT

Polypropylene random crystallinity temperature (PP-RCT), also used for plastic pipework, is a new form of this plastic. It achieves higher strength at high temperature by β-crystallization.

Degradation

Polypropylene is liable to chain degradation from exposure to temperatures above 100 °C. Oxidation usually occurs at the tertiary carbon centers leading to chain breaking via reaction with oxygen. In external applications, degradation is evidenced by cracks and crazing. It may be protected by the use of various polymer stabilizers, including UV-absorbing additives and anti-oxidants such as phosphites (e.g. tris(2,4-di-tert-butylphenyl)phosphite) and hindered phenols, which prevent polymer degradation.

Microbial communities isolated from soil samples mixed with starch have been shown to be capable of degrading polypropylene. Polypropylene has been reported to degrade while in the human body as implantable mesh devices. The degraded material forms a tree bark-like layer at the surface of mesh fibers.

Optical properties

PP can be made translucent when uncolored but is not as readily made transparent as polystyrene, acrylic, or certain other plastics. It is often opaque or colored using pigments.

Production

Polypropylene is produced by the chain-growth polymerization of propene:

The industrial production processes can be grouped into gas phase polymerization, bulk polymerization and slurry polymerization. All state-of-the-art processes use either gas-phase or bulk reactor systems.

- In gas-phase and slurry-reactors, the polymer is formed around heterogeneous catalyst particles. The gas-phase polymerization is carried out in a fluidized bed reactor, propene is passed over a bed containing the heterogeneous (solid) catalyst and the formed polymer is separated as a fine powder and then converted into pellets. Unreacted gas is recycled and fed back into the reactor.

- In bulk polymerization, liquid propene acts as a solvent to prevent the precipitation of the polymer. The polymerization proceeds at 60 to 80 °C and 30–40 atm are applied to keep the propene in the liquid state. For the bulk polymerization, typically loop reactors are applied. The bulk polymerization is limited to a maximum of 5% ethene as comonomer due to a limited solubility of the polymer in the liquid propene.

- In the slurry polymerization, typically C4–C6 alkanes (butane, pentane or hexane) are utilized as inert diluent to suspend the growing polymer particles. Propene is introduced into the mixture as a gas.

Catalysts

The properties of PP are strongly affected by its tacticity, the orientation of the methyl groups (CH

3) relative to the methyl groups in neighboring monomer units. A Ziegler–Natta catalyst is able to restrict linking of monomer molecules to a specific orientation, either isotactic, when all methyl groups are positioned at the same side with respect to the backbone of the polymer chain, or syndiotactic, when the positions of the methyl groups alternate.

Commercially available isotactic polypropylene is made with two types of Ziegler-Natta catalysts. The first group of the catalysts encompasses solid (mostly supported) catalysts and certain types of soluble metallocene catalysts. Such isotactic macromolecules coil into a helical shape; these helices then line up next to one another to form the crystals that give commercial isotactic polypropylene many of its desirable properties.

Modern supported Ziegler-Natta catalysts developed for the polymerization of propylene and other 1-alkenes to isotactic polymers usually use TiCl

4 as an active ingredient and MgCl

2 as a support. The catalysts also contain organic modifiers, either aromatic acid esters and diesters or ethers. These catalysts are activated with special co-catalysts containing an organoaluminium compound such as Al(C2H5)3 and the second type of a modifier. The catalysts are differentiated depending on the procedure used for fashioning catalyst particles from MgCl2 and depending on the type of organic modifiers employed during catalyst preparation and use in polymerization reactions. Two most important technological characteristics of all the supported catalysts are high productivity and a high fraction of the crystalline isotactic polymer they produce at 70–80 °C under standard polymerization conditions. Commercial synthesis of isotactic polypropylene is usually carried out either in the medium of liquid propylene or in gas-phase reactors.

Commercial synthesis of syndiotactic polypropylene is carried out with the use of a special class of metallocene catalysts. They employ bridged bis-metallocene complexes of the type bridge-(Cp1)(Cp2)ZrCl2 where the first Cp ligand is the cyclopentadienyl group, the second Cp ligand is the fluorenyl group, and the bridge between the two Cp ligands is -CH2-CH2-, >SiMe2, or >SiPh2. These complexes are converted to polymerization catalysts by activating them with a special organoaluminium co-catalyst, methylaluminoxane (MAO).

Atactic polypropylene is an amorphous rubbery material. It can be produced commercially either with a special type of supported Ziegler-Natta catalyst or with some metallocene catalysts.

Manufacturing from polypropylene

Melting process of polypropylene can be achieved via extrusion and molding. Common extrusion methods include production of melt-blown and spun-bond fibers to form long rolls for future conversion into a wide range of useful products, such as face masks, filters, diapers and wipes.

The most common shaping technique is injection molding, which is used for parts such as cups, cutlery, vials, caps, containers, housewares, and automotive parts such as batteries. The related techniques of blow molding and injection-stretch blow molding are also used, which involve both extrusion and molding.

The large number of end-use applications for polypropylene are often possible because of the ability to tailor grades with specific molecular properties and additives during its manufacture. For example, antistatic additives can be added to help polypropylene surfaces resist dust and dirt. Many physical finishing techniques can also be used on polypropylene, such as machining. Surface treatments can be applied to polypropylene parts in order to promote adhesion of printing ink and paints.

Expanded Polypropylene (EPP) has been produced through both solid and melt state processing. EPP is manufactured using melt processing with either chemical or physical blowing agents. Expansion of PP in solid state, due to its highly crystalline structure, has not been successful. In this regard, two novel strategies were developed for expansion of PP. It was observed that PP can be expanded to make EPP through controlling its crystalline structure or through blending with other polymers.

Biaxially oriented polypropylene (BOPP)

When polypropylene film is extruded and stretched in both the machine direction and across machine direction it is called biaxially oriented polypropylene. Two methods are widely used for producing BOPP films, namely, a bi-directional stenter process or a double-bubble blown film extrusion process. Biaxial orientation increases strength and clarity. BOPP is widely used as a packaging material for packaging products such as snack foods, fresh produce and confectionery. It is easy to coat, print and laminate to give the required appearance and properties for use as a packaging material. This process is normally called converting. It is normally produced in large rolls which are slit on slitting machines into smaller rolls for use on packaging machines. BOPP is also used for stickers and labels in addition to OPP. It is non-reactive, which makes BOPP suitable for safe use in the pharmaceutical and food industry. It is one of the most important commercial polyolefin films. BOPP films are available in different thicknesses and widths. They are transparent and flexible.

Applications

As polypropylene is resistant to fatigue, most plastic living hinges, such as those on flip-top bottles, are made from this material. However, it is important to ensure that chain molecules are oriented across the hinge to maximise strength.

Polypropylene is used in the manufacturing of piping systems, both ones concerned with high purity and ones designed for strength and rigidity (e.g., those intended for use in potable plumbing, hydronic heating and cooling, and reclaimed water). This material is often chosen for its resistance to corrosion and chemical leaching, its resilience against most forms of physical damage, including impact and freezing, its environmental benefits, and its ability to be joined by heat fusion rather than gluing.

Many plastic items for medical or laboratory use can be made from polypropylene because it can withstand the heat in an autoclave. Its heat resistance also enables it to be used as the manufacturing material of consumer-grade kettles. Food containers made from it will not melt in the dishwasher, and do not melt during industrial hot filling processes. For this reason, most plastic tubs for dairy products are polypropylene sealed with aluminum foil (both heat-resistant materials). After the product has cooled, the tubs are often given lids made of a less heat-resistant material, such as LDPE or polystyrene. Such containers provide a good hands-on example of the difference in modulus, since the rubbery (softer, more flexible) feeling of LDPE with respect to polypropylene of the same thickness is readily apparent. Rugged, translucent, reusable plastic containers made in a wide variety of shapes and sizes for consumers from various companies such as Rubbermaid and Sterilite are commonly made of polypropylene, although the lids are often made of somewhat more flexible LDPE so they can snap onto the container to close it. Polypropylene can also be made into disposable bottles to contain liquid, powdered, or similar consumer products, although HDPE and polyethylene terephthalate are commonly also used to make bottles. Plastic pails, car batteries, wastebaskets, pharmacy prescription bottles, cooler containers, dishes and pitchers are often made of polypropylene or HDPE, both of which commonly have rather similar appearance, feel, and properties at ambient temperature. An abundance of medical devices are made from PP.

A common application for polypropylene is as biaxially oriented polypropylene (BOPP). These BOPP sheets are used to make a wide variety of materials including clear bags. When polypropylene is biaxially oriented, it becomes crystal clear and serves as an excellent packaging material for artistic and retail products.

Polypropylene, highly colorfast, is widely used in manufacturing carpets, rugs and mats to be used at home.

Polypropylene is widely used in ropes, distinctive because they are light enough to float in water. For equal mass and construction, polypropylene rope is similar in strength to polyester rope. Polypropylene costs less than most other synthetic fibers.

Polypropylene is also used as an alternative to polyvinyl chloride (PVC) as insulation for electrical cables for LSZH cable in low-ventilation environments, primarily tunnels. This is because it emits less smoke and no toxic halogens, which may lead to production of acid in high-temperature conditions.

Polypropylene is also used in particular roofing membranes as the waterproofing top layer of single-ply systems as opposed to modified-bit systems.

Polypropylene is most commonly used for plastic moldings, wherein it is injected into a mold while molten, forming complex shapes at relatively low cost and high volume; examples include bottle tops, bottles, and fittings.

It can also be produced in sheet form, widely used for the production of stationery folders, packaging, and storage boxes. The wide color range, durability, low cost, and resistance to dirt make it ideal as a protective cover for papers and other materials. It is used in Rubik's Cube stickers because of these characteristics.

The availability of sheet polypropylene has provided an opportunity for the use of the material by designers. The light-weight, durable, and colorful plastic makes an ideal medium for the creation of light shades, and a number of designs have been developed using interlocking sections to create elaborate designs.

Polypropylene fibres are used as a concrete additive to increase strength and reduce cracking and spalling. In some areas susceptible to earthquakes (e.g., California), PP fibers are added with soils to improve the soil's strength and damping when constructing the foundation of structures such as buildings, bridges, etc.

Clothing

Polypropylene is a major polymer used in nonwovens, with over 50% used for diapers or sanitary products where it is treated to absorb water (hydrophilic) rather than naturally repelling water (hydrophobic). Other non-woven uses include filters for air, gas, and liquids in which the fibers can be formed into sheets or webs that can be pleated to form cartridges or layers that filter in various efficiencies in the 0.5 to 30 micrometre range. Such applications occur in houses as water filters or in air-conditioning-type filters. The high surface-area and naturally oleophilic polypropylene nonwovens are ideal absorbers of oil spills with the familiar floating barriers near oil spills on rivers.

Polypropylene, or 'polypro', has been used for the fabrication of cold-weather base layers, such as long-sleeve shirts or long underwear. Polypropylene is also used in warm-weather clothing, in which it transports sweat away from the skin. Polyester has replaced polypropylene in these applications in the U.S. military, such as in the ECWCS. Although polypropylene clothes are not easily flammable, they can melt, which may result in severe burns if the wearer is involved in an explosion or fire of any kind. Polypropylene undergarments are known for retaining body odors which are then difficult to remove. The current generation of polyester does not have this disadvantage.

Medical

Its most common medical use is in the synthetic, nonabsorbable suture Prolene, manufactured by Ethicon Inc.

Polypropylene has been used in hernia and pelvic organ prolapse repair operations to protect the body from new hernias in the same location. A small patch of the material is placed over the spot of the hernia, below the skin, and is painless and rarely, if ever, rejected by the body. However, a polypropylene mesh will erode the tissue surrounding it over the uncertain period from days to years.

A notable application was as a transvaginal mesh, used to treat vaginal prolapse and concurrent urinary incontinence. Due to the above-mentioned propensity for polypropylene mesh to erode the tissue surrounding it, the FDA has issued several warnings on the use of polypropylene mesh medical kits for certain applications in pelvic organ prolapse, specifically when introduced in close proximity to the vaginal wall due to a continued increase in number of mesh-driven tissue erosions reported by patients over the past few years. On 3 January 2012, the FDA ordered 35 manufacturers of these mesh products to study the side effects of these devices. Due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the demand for PP has increased significantly because it is a vital raw material for producing meltblown fabric, which is in turn the raw material for producing facial masks.

Recycling

Further information: Plastic recyclingMost polypropylene recycling uses mechanical recycling, as for polyethylene: the material is heated to soften or melt it, and mechanically formed it into new products. As of 2015, less than 1% of polypropylene generated was recycled. Heating degrades the carbon backbone more severely than for polyethylene, breaking it into smaller organic molecules, because the methyl side group of PP is susceptible to thermo-oxidative and photo-oxidative degradation.

Polypropylene has the number "5" as its resin identification code:

Repairing

PP objects can be joined with a two-part epoxy glue or using hot-glue guns.

PP can be melted using a speed tip welding technique. With speed welding, the plastic welder, similar to a soldering iron in appearance and wattage, is fitted with a feed tube for the plastic weld rod. The speed tip heats the rod and the substrate, while at the same time it presses the molten weld rod into position. A bead of softened plastic is laid into the joint and the parts and weld rod fuse. With polypropylene, the melted welding rod must be "mixed" with the semi-melted base material being fabricated or repaired. A speed tip "gun" is essentially a soldering iron with a broad, flat tip that can be used to melt the weld joint and filler material to create a bond.

Health concerns

The advocacy organization Environmental Working Group classifies PP as of low hazard. PP is dope-dyed; no water is used in its dyeing, in contrast with cotton. Polypropylene was the most common microplastic fiber found in the olfactory bulbs in 8 of 15 deceased individuals in a study.

Combustibility

Like all organic compounds, polypropylene is combustible. The flash point of a typical composition is 260 °C; autoignition temperature is 388 °C.

References

- ^ Gahleitner, Markus; Paulik, Christian (2014). "Polypropylene". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–44. doi:10.1002/14356007.o21_o04.pub2. ISBN 9783527306732.

- Stinson, Stephen (1987). "Discoverers of Polypropylene Share Prize". Chemical & Engineering News. 65 (10): 30. doi:10.1021/cen-v065n010.p030.

- Morris, Peter J. T. (2005). Polymer Pioneers: A Popular History of the Science and Technology of Large Molecules. Chemical Heritage Foundation. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-941901-03-1.

- "This week 50 years ago". New Scientist. 28 April 2007. p. 15.

- Wang, Suxi; Muiruri, Joseph Kinyanjui; Soo, Xiang Yun Debbie; Liu, Songlin; Thitsartarn, Warintorn; Tan, Beng Hoon; Suwardi, Ady; Li, Zibiao; Zhu, Qiang; Loh, Xian Jun (2023-01-17). "Bio-Polypropylene and Polypropylene-based Biocomposites: Solutions for a Sustainable Future". Chemistry: An Asian Journal. 18 (2): e202200972. doi:10.1002/asia.202200972. ISSN 1861-4728. PMID 36461701. S2CID 253825228.

- ^ Tripathi, D. (2001). Practical guide to polypropylene. Shrewsbury: RAPRA Technology. ISBN 978-1859572825.

- "Polypropylene Plastic Materials & Fibers by Porex". www.porex.com. Archived from the original on 2016-11-14. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- ^ Maier, Clive; Calafut, Teresa (1998). Polypropylene: the definitive user's guide and databook. William Andrew. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-884207-58-7.

- ^ Kaiser, Wolfgang (2011). Kunststoffchemie für Ingenieure von der Synthese bis zur Anwendung [Plastics chemistry for engineers from synthesis to application] (in German) (3rd ed.). München: Hanser. p. 247. ISBN 978-3-446-43047-1.

- "10.4: Synthesis of Polymers". LibreTexts.

- Nuyken, von Sebastian; Koltzenburg, Michael; Maskos, Oskar (2013). Polymere: Synthese, Eigenschaften und Anwendungen [Polymers: synthesis, properties and applications] (in German) (1st ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-34772-6.

- ^ Hans., Domininghaus (2011). Kunststoffe : Eigenschaften und Anwendungen (8., bearb. Aufl ed.). Berlin: Springer Berlin. ISBN 9783642161728. OCLC 706947259.

- Jones, A. Turner; Wood, Jean M; Beckett, D. R. (1964). "Crystalline forms of isotactic polypropylene". Die Marco Chain. 75 (1): 134–58. doi:10.1002/macp.1964.020750113.

- Fischer, G. (1988). Deformations- und Versagensmechanismen von isotaktischem Polyp(i-PP) obrhalb dr Glasübergangstemperatur [Deformations- und Versagensmechanismen von isotaktischem Polypropylen (i-PP) oberhalb der Glasübergangstemperatur] (PhD Thesis) (in German). Universität Stuttgart. OCLC 441127075.

- ^ Samuels, Robert J (1975). "Quantitative structural characterization of the melting behavior of isotactic polypropylene". Journal of Polymer Science: Polymer Physics Edition. 13 (7): 1417–46. Bibcode:1975JPoSB..13.1417S. doi:10.1002/pol.1975.180130713.

- Yadav, Y.S; Jain, P.C (1986). "Melting behaviour of isotactic polypropylene isothermally crystallized from the melt". Polymer. 27 (5): 721–7. doi:10.1016/0032-3861(86)90130-8.

- ^ Cox, W. W; Duswalt, A. A (1967). "Morphological transformations of polypropylene related to its melting and recrystallization behavior". Polymer Engineering and Science. 7 (4): 309–16. doi:10.1002/pen.760070412.

- Bassett, D.C; Olley, R.H (1984). "On the lamellar morphology of isotactic polypropylene spherulites". Polymer. 25 (7): 935–46. doi:10.1016/0032-3861(84)90076-4.

- Bai, Feng; Li, Fuming; Calhoun, Bret H; Quirk, Roderic P; Cheng, Stephen Z. D (2003). "Physical Constants of Poly(propylene)". The Wiley Database of Polymer Properties. doi:10.1002/0471532053.bra025. ISBN 978-0-471-53205-7.

- ^ Shi, Guan-yi; Zhang, Xiao-Dong; Cao, You-Hong; Hong, Jie (1993). "Melting behavior and crystalline order of ß-crystalline phase poly(propylene)". Die Makromolekulare Chemie. 194 (1): 269–77. doi:10.1002/macp.1993.021940123.

- Farina, Mario; Di Silvestro, Giuseppe; Terragni, Alberto (1995). "A stereochemical and statistical analysis of metallocene-promoted polymerization". Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 196 (1): 353–67. doi:10.1002/macp.1995.021960125.

- Varga, J (1992). "Supermolecular structure of isotactic polypropylene". Journal of Materials Science. 27 (10): 2557–79. Bibcode:1992JMatS..27.2557V. doi:10.1007/BF00540671. S2CID 137665080.

- Lovinger, Andrew J; Chua, Jaime O; Gryte, Carl C (1977). "Studies on the α and β forms of isotactic polypropylene by crystallization in a temperature gradient". Journal of Polymer Science: Polymer Physics Edition. 15 (4): 641–56. Bibcode:1977JPoSB..15..641L. doi:10.1002/pol.1977.180150405.

- Binsbergen, F.L; De Lange, B.G.M (1968). "Morphology of polypropylene crystallized from the melt". Polymer. 9: 23–40. doi:10.1016/0032-3861(68)90006-2.

- De Rosa, C; Auriemma, F (2006). "Structure and physical properties of syndiotactic polypropylene: A highly crystalline thermoplastic elastomer". Progress in Polymer Science. 31 (2): 145–237. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2005.11.002.

- Galambos, Adam; Wolkowicz, Michael; Zeigler, Robert (1992). "Structure and Morphology of Highly Stereoregular Syndiotactic Polypropylene Produced by Homogeneous Catalysts". Catalysis in Polymer Synthesis. ACS Symposium Series. Vol. 496. pp. 104–20. doi:10.1021/bk-1992-0496.ch008. ISBN 978-0-8412-2456-8.

- Rodriguez-Arnold, Jonahira; Zhang, Anqiu; Cheng, Stephen Z.D; Lovinger, Andrew J; Hsieh, Eric T; Chu, Peter; Johnson, Tim W; Honnell, Kevin G; Geerts, Rolf G; Palackal, Syriac J; Hawley, Gil R; Welch, M.Bruce (1994). "Crystallization, melting and morphology of syndiotactic polypropylene fractions: 1. Thermodynamic properties, overall crystallization and melting". Polymer. 35 (9): 1884–95. doi:10.1016/0032-3861(94)90978-4.

- Wolfgang, Kaiser (2007). Kunststoffchemie für Ingenieure: von der Synthese bis zur Anwendung [Plastics chemistry for engineers: from synthesis to application] (in German) (2nd ed.). München: Hanser. p. 251. ISBN 978-3-446-41325-2. OCLC 213395068.

- "Novinky v produkci FV Plast - od PP-R k PP-RCT". FV - Plast, a.s., Czech Republic. Archived from the original on 2019-11-30. Retrieved 2019-11-30.

- Cacciari, I; Quatrini, P; Zirletta, G; Mincione, E; Vinciguerra, V; Lupattelli, P; Giovannozzi Sermanni, G (1993). "Isotactic polypropylene biodegradation by a microbial community: Physicochemical characterization of metabolites produced". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 59 (11): 3695–700. Bibcode:1993ApEnM..59.3695C. doi:10.1128/AEM.59.11.3695-3700.1993. PMC 182519. PMID 8285678.

- Iakovlev, Vladimir V; Guelcher, Scott A; Bendavid, Robert (2017). "Degradation of polypropylene in vivo: A microscopic analysis of meshes explanted from patients". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 105 (2): 237–48. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.33502. PMID 26315946.

- Kissin, Y. V. (2008). Alkene Polymerization Reactions with Transition Metal Catalysts. Elsevier. pp. 207–. ISBN 978-0-444-53215-2.

- Hoff, Ray & Mathers, Robert T. (2010). Handbook of Transition Metal Polymerization Catalysts. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-0-470-13798-7.

- Moore, E. P. (1996). Polypropylene Handbook. Polymerization, Characterization, Properties, Processing, Applications. New York: Hanser Publishers. ISBN 1569902089.

- Benedikt, G. M.; Goodall, B. L., eds. (1998). Metallocene Catalyzed Polymers. Toronto: ChemTech Publishing. ISBN 978-1-884207-59-4.

- Sinn, H.; Kaminsky, W.; Höker, H., eds. (1995). Alumoxanes, Macromol. Symp. 97. Heidelberg: Huttig & Wepf.

- Doroudiani, Saeed; Park, Chul B; Kortschot, Mark T (1996). "Effect of the crystallinity and morphology on the microcellular foam structure of semicrystalline polymers". Polymer Engineering & Science. 36 (21): 2645–62. doi:10.1002/pen.10664.

- Doroudiani, Saeed; Park, Chul B; Kortschot, Mark T (1998). "Processing and characterization of microcellular foamed high-density polyethylene/isotactic polypropylene blends". Polymer Engineering & Science. 38 (7): 1205–15. doi:10.1002/pen.10289.

- "Polypropylene Applications". Euroshore. 25 May 2021. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- "Biaxially Oriented Polypropylene Films". Granwell. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- Neagu, Cristina (2020-02-05). "What is BOPP?". Sticker Mule. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- Specification for Pressure-rated Polypropylene (PP) Piping Systems, West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International, 2017, doi:10.1520/f2389-17a

- Green pipe helps miners remove the black Contractor Magazine, 10 January 2010

- Contractor Retrofits His Business. the News/ 2 November 2009.

- What to do when the piping replacement needs a replacement? Engineered Systems. 1 November 2009.

- Collinet, Pierre; Belot, Franck; Debodinance, Philippe; Duc, Edouard Ha; Lucot, Jean-Philippe; Cosson, Michel (2006-08-01). "Transvaginal mesh technique for pelvic organ prolapse repair: mesh exposure management and risk factors". International Urogynecology Journal. 17 (4): 315–320. doi:10.1007/s00192-005-0003-8. ISSN 0937-3462. PMID 16228121. S2CID 2648056.

- Rug fibers Archived 2010-04-05 at the Wayback Machine. Fibersource.com. Retrieved on 2012-05-31.

- Braided Polypropylene Rope is Inexpensive and it Floats. contractorrope.com. Retrieved on 2013-02-28.

- Bayasi, Ziad & Zeng, Jack (1993). "Properties of Polypropylene Fiber Reinforced Concrete". ACI Materials Journal. 90 (6): 605–610. doi:10.14359/4439.

- Amir-Faryar, Behzad & Aggour, M. Sherif (2015). "Effect of fibre inclusion on dynamic properties of clay". Geomechanics and Geoengineering. 11 (2): 1–10. doi:10.1080/17486025.2015.1029013. S2CID 128478509.

- Generation III Extended Cold Weather Clothing System (ECWCS). PM Soldier Equipment. October 2008

- USAF Flying Magazine. Safety. Nov. 2002. access.gpo.gov

- Ellis, David. Get Real: The true story of performance next to skin fabrics. outdoorsnz.org.nz

- Collinet, Pierre; Belot, Franck; Debodinance, Philippe; Duc, Edouard Ha; Lucot, Jean-Philippe; Cosson, Michel (2006-08-01). "Transvaginal mesh technique for pelvic organ prolapse repair: mesh exposure management and risk factors". International Urogynecology Journal. 17 (4): 315–320. doi:10.1007/s00192-005-0003-8. ISSN 0937-3462. PMID 16228121. S2CID 2648056.

- UPDATE on Serious Complications Associated with Transvaginal Placement of Surgical Mesh for Pelvic Organ Prolapse: FDA Safety Communication, FDA, July 13, 2011

- Li, Houqian; Aguirre-Villegas, Horacio A.; Allen, Robert D.; Bai, Xianglan; Benson, Craig H.; et al. (2022). "Expanding plastics recycling technologies: chemical aspects, technology status and challenges". Green Chemistry. 24 (23): 8899–9002. doi:10.1039/D2GC02588D. ISSN 1463-9262.

- ^ Thiounn, Timmy; Smith, Rhett C. (2020). "Advances and approaches for chemical recycling of plastic waste". Journal of Polymer Science. 58 (10): 1347–1364. doi:10.1002/pol.20190261. ISSN 2642-4150.

- Plastics recycling information sheet Archived 2010-07-22 at the Wayback Machine, Waste Online

- Athavale, Shrikant P. (20 September 2018). Hand Book of Printing, Packaging and Lamination: Packaging Technology. Notion Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-64429-251-8.

- Polypropylene || Skin Deep Cosmetics Database | Environmental Working Group. ewg.com. Retrieved on 2024-07-02.

- Chapagain, A. K. et al. (September 2005) The water footprint of cotton consumption. UNESCO-IHE Delft. Value of Water Research Report Series No. 18. waterfootprint.org

- Luís Fernando Amato-Lourenço, PhD1,2; Katia Cristina Dantas, PhD2; Gabriel Ribeiro Júnior, PhD2; et al (September 16, 2024) Microplastics in the Olfactory Bulb of the Human Brain JAMA Network Open Original Investigation Environmental Health

- Shields, T. J.; Zhang, J. (1999). "Fire hazard with polypropylene". Polypropylene. Polymer Science and Technology Series. Vol. 2. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 247–253. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-4421-6_34. ISBN 978-94-010-5899-5.

- "A&C Plastics Polypropylene MSDS" (PDF).

External links

- Chain structure of Polypropylene

- Polypropylene on Plastipedia

- Polypropylene Properties & other information