In mathematics, a chain complex is an algebraic structure that consists of a sequence of abelian groups (or modules) and a sequence of homomorphisms between consecutive groups such that the image of each homomorphism is contained in the kernel of the next. Associated to a chain complex is its homology, which is (loosely speaking) a measure of the failure of a chain complex to be exact.

A cochain complex is similar to a chain complex, except that its homomorphisms are in the opposite direction. The homology of a cochain complex is called its cohomology.

In algebraic topology, the singular chain complex of a topological space X is constructed using continuous maps from a simplex to X, and the homomorphisms of the chain complex capture how these maps restrict to the boundary of the simplex. The homology of this chain complex is called the singular homology of X, and is a commonly used invariant of a topological space.

Chain complexes are studied in homological algebra, but are used in several areas of mathematics, including abstract algebra, Galois theory, differential geometry and algebraic geometry. They can be defined more generally in abelian categories.

Definitions

A chain complex is a sequence of abelian groups or modules ..., A0, A1, A2, A3, A4, ... connected by homomorphisms (called boundary operators or differentials) dn : An → An−1, such that the composition of any two consecutive maps is the zero map. Explicitly, the differentials satisfy dn ∘ dn+1 = 0, or with indices suppressed, d = 0. The complex may be written out as follows.

The cochain complex is the dual notion to a chain complex. It consists of a sequence of abelian groups or modules ..., A, A, A, A, A, ... connected by homomorphisms d : A → A satisfying d ∘ d = 0. The cochain complex may be written out in a similar fashion to the chain complex.

The index n in either An or A is referred to as the degree (or dimension). The difference between chain and cochain complexes is that, in chain complexes, the differentials decrease dimension, whereas in cochain complexes they increase dimension. All the concepts and definitions for chain complexes apply to cochain complexes, except that they will follow this different convention for dimension, and often terms will be given the prefix co-. In this article, definitions will be given for chain complexes when the distinction is not required.

A bounded chain complex is one in which almost all the An are 0; that is, a finite complex extended to the left and right by 0. An example is the chain complex defining the simplicial homology of a finite simplicial complex. A chain complex is bounded above if all modules above some fixed degree N are 0, and is bounded below if all modules below some fixed degree are 0. Clearly, a complex is bounded both above and below if and only if the complex is bounded.

The elements of the individual groups of a (co)chain complex are called (co)chains. The elements in the kernel of d are called (co)cycles (or closed elements), and the elements in the image of d are called (co)boundaries (or exact elements). Right from the definition of the differential, all boundaries are cycles. The n-th (co)homology group Hn (H) is the group of (co)cycles modulo (co)boundaries in degree n, that is,

Exact sequences

Main article: Exact sequenceAn exact sequence (or exact complex) is a chain complex whose homology groups are all zero. This means all closed elements in the complex are exact. A short exact sequence is a bounded exact sequence in which only the groups Ak, Ak+1, Ak+2 may be nonzero. For example, the following chain complex is a short exact sequence.

In the middle group, the closed elements are the elements pZ; these are clearly the exact elements in this group.

Chain maps

A chain map f between two chain complexes and is a sequence of homomorphisms for each n that commutes with the boundary operators on the two chain complexes, so . This is written out in the following commutative diagram.

A chain map sends cycles to cycles and boundaries to boundaries, and thus induces a map on homology .

A continuous map f between topological spaces X and Y induces a chain map between the singular chain complexes of X and Y, and hence induces a map f* between the singular homology of X and Y as well. When X and Y are both equal to the n-sphere, the map induced on homology defines the degree of the map f.

The concept of chain map reduces to the one of boundary through the construction of the cone of a chain map.

Chain homotopy

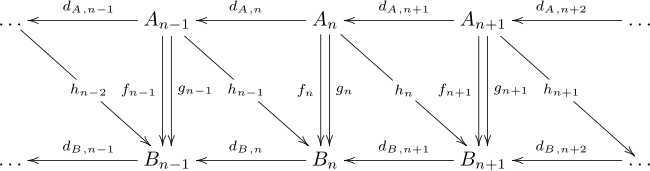

See also: Homotopy category of chain complexesA chain homotopy offers a way to relate two chain maps that induce the same map on homology groups, even though the maps may be different. Given two chain complexes A and B, and two chain maps f, g : A → B, a chain homotopy is a sequence of homomorphisms hn : An → Bn+1 such that hdA + dBh = f − g. The maps may be written out in a diagram as follows, but this diagram is not commutative.

The map hdA + dBh is easily verified to induce the zero map on homology, for any h. It immediately follows that f and g induce the same map on homology. One says f and g are chain homotopic (or simply homotopic), and this property defines an equivalence relation between chain maps.

Let X and Y be topological spaces. In the case of singular homology, a homotopy between continuous maps f, g : X → Y induces a chain homotopy between the chain maps corresponding to f and g. This shows that two homotopic maps induce the same map on singular homology. The name "chain homotopy" is motivated by this example.

Examples

Singular homology

Main article: Singular homologyLet X be a topological space. Define Cn(X) for natural n to be the free abelian group formally generated by singular n-simplices in X, and define the boundary map to be

where the hat denotes the omission of a vertex. That is, the boundary of a singular simplex is the alternating sum of restrictions to its faces. It can be shown that ∂ = 0, so is a chain complex; the singular homology is the homology of this complex.

Singular homology is a useful invariant of topological spaces up to homotopy equivalence. The degree zero homology group is a free abelian group on the path-components of X.

de Rham cohomology

Main article: de Rham cohomologyThe differential k-forms on any smooth manifold M form a real vector space called Ω(M) under addition. The exterior derivative d maps Ω(M) to Ω(M), and d = 0 follows essentially from symmetry of second derivatives, so the vector spaces of k-forms along with the exterior derivative are a cochain complex.

The cohomology of this complex is called the de Rham cohomology of M. Locally constant functions are designated with its isomorphism with c the count of mutually disconnected components of M. This way the complex was extended to leave the complex exact at zero-form level using the subset operator.

Smooth maps between manifolds induce chain maps, and smooth homotopies between maps induce chain homotopies.

Category of chain complexes

Chain complexes of K-modules with chain maps form a category ChK, where K is a commutative ring.

If V = V and W = W are chain complexes, their tensor product is a chain complex with degree n elements given by

and differential given by

where a and b are any two homogeneous vectors in V and W respectively, and denotes the degree of a.

This tensor product makes the category ChK into a symmetric monoidal category. The identity object with respect to this monoidal product is the base ring K viewed as a chain complex in degree 0. The braiding is given on simple tensors of homogeneous elements by

The sign is necessary for the braiding to be a chain map.

Moreover, the category of chain complexes of K-modules also has internal Hom: given chain complexes V and W, the internal Hom of V and W, denoted Hom(V,W), is the chain complex with degree n elements given by and differential given by

- .

We have a natural isomorphism

Further examples

- Amitsur complex

- A complex used to define Bloch's higher Chow groups

- Buchsbaum–Rim complex

- Čech complex

- Cousin complex

- Eagon–Northcott complex

- Gersten complex

- Graph complex

- Koszul complex

- Moore complex

- Schur complex

See also

- Differential graded algebra

- Differential graded Lie algebra

- Dold–Kan correspondence says there is an equivalence between the category of chain complexes and the category of simplicial abelian groups.

- Buchsbaum–Eisenbud acyclicity criterion

- Differential graded module

References

- Bott, Raoul; Tu, Loring W. (1982), Differential Forms in Algebraic Topology, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90613-3

- Hatcher, Allen (2002). Algebraic Topology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79540-0.

is a sequence of abelian groups or modules ..., A0, A1, A2, A3, A4, ... connected by homomorphisms (called boundary operators or differentials) dn : An → An−1, such that the composition of any two consecutive maps is the zero map. Explicitly, the differentials satisfy dn ∘ dn+1 = 0, or with indices suppressed, d = 0. The complex may be written out as follows.

is a sequence of abelian groups or modules ..., A0, A1, A2, A3, A4, ... connected by homomorphisms (called boundary operators or differentials) dn : An → An−1, such that the composition of any two consecutive maps is the zero map. Explicitly, the differentials satisfy dn ∘ dn+1 = 0, or with indices suppressed, d = 0. The complex may be written out as follows.

is the

is the

and

and  is a sequence

is a sequence  of homomorphisms

of homomorphisms  for each n that commutes with the boundary operators on the two chain complexes, so

for each n that commutes with the boundary operators on the two chain complexes, so  . This is written out in the following

. This is written out in the following

.

.

to be

to be

is a chain complex; the singular homology

is a chain complex; the singular homology  is the homology of this complex.

is the homology of this complex.

with c the count of mutually disconnected components of M. This way the complex was extended to leave the complex exact at zero-form level using the subset operator.

with c the count of mutually disconnected components of M. This way the complex was extended to leave the complex exact at zero-form level using the subset operator.

and W = W

and W = W is a chain complex with degree n elements given by

is a chain complex with degree n elements given by

denotes the degree of a.

denotes the degree of a.

and differential given by

and differential given by

.

.