| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Paraboloid" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In geometry, a paraboloid is a quadric surface that has exactly one axis of symmetry and no center of symmetry. The term "paraboloid" is derived from parabola, which refers to a conic section that has a similar property of symmetry.

Every plane section of a paraboloid made by a plane parallel to the axis of symmetry is a parabola. The paraboloid is hyperbolic if every other plane section is either a hyperbola, or two crossing lines (in the case of a section by a tangent plane). The paraboloid is elliptic if every other nonempty plane section is either an ellipse, or a single point (in the case of a section by a tangent plane). A paraboloid is either elliptic or hyperbolic.

Equivalently, a paraboloid may be defined as a quadric surface that is not a cylinder, and has an implicit equation whose part of degree two may be factored over the complex numbers into two different linear factors. The paraboloid is hyperbolic if the factors are real; elliptic if the factors are complex conjugate.

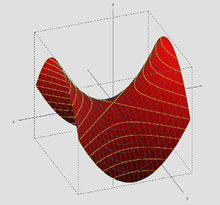

An elliptic paraboloid is shaped like an oval cup and has a maximum or minimum point when its axis is vertical. In a suitable coordinate system with three axes x, y, and z, it can be represented by the equation where a and b are constants that dictate the level of curvature in the xz and yz planes respectively. In this position, the elliptic paraboloid opens upward.

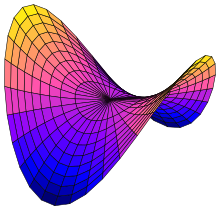

A hyperbolic paraboloid (not to be confused with a hyperboloid) is a doubly ruled surface shaped like a saddle. In a suitable coordinate system, a hyperbolic paraboloid can be represented by the equation In this position, the hyperbolic paraboloid opens downward along the x-axis and upward along the y-axis (that is, the parabola in the plane x = 0 opens upward and the parabola in the plane y = 0 opens downward).

Any paraboloid (elliptic or hyperbolic) is a translation surface, as it can be generated by a moving parabola directed by a second parabola.

Properties and applications

Elliptic paraboloid

In a suitable Cartesian coordinate system, an elliptic paraboloid has the equation

If a = b, an elliptic paraboloid is a circular paraboloid or paraboloid of revolution. It is a surface of revolution obtained by revolving a parabola around its axis.

A circular paraboloid contains circles. This is also true in the general case (see Circular section).

From the point of view of projective geometry, an elliptic paraboloid is an ellipsoid that is tangent to the plane at infinity.

- Plane sections

The plane sections of an elliptic paraboloid can be:

- a parabola, if the plane is parallel to the axis,

- a point, if the plane is a tangent plane.

- an ellipse or empty, otherwise.

Parabolic reflector

Main articles: Parabolic reflector and parabolic antennaOn the axis of a circular paraboloid, there is a point called the focus (or focal point), such that, if the paraboloid is a mirror, light (or other waves) from a point source at the focus is reflected into a parallel beam, parallel to the axis of the paraboloid. This also works the other way around: a parallel beam of light that is parallel to the axis of the paraboloid is concentrated at the focal point. For a proof, see Parabola § Proof of the reflective property.

Therefore, the shape of a circular paraboloid is widely used in astronomy for parabolic reflectors and parabolic antennas.

The surface of a rotating liquid is also a circular paraboloid. This is used in liquid-mirror telescopes and in making solid telescope mirrors (see rotating furnace).

-

Parallel rays coming into a circular paraboloidal mirror are reflected to the focal point, F, or vice versa

Parallel rays coming into a circular paraboloidal mirror are reflected to the focal point, F, or vice versa

-

Parabolic reflector

Parabolic reflector

-

Rotating water in a glass

Hyperbolic paraboloid

The hyperbolic paraboloid is a doubly ruled surface: it contains two families of mutually skew lines. The lines in each family are parallel to a common plane, but not to each other. Hence the hyperbolic paraboloid is a conoid.

These properties characterize hyperbolic paraboloids and are used in one of the oldest definitions of hyperbolic paraboloids: a hyperbolic paraboloid is a surface that may be generated by a moving line that is parallel to a fixed plane and crosses two fixed skew lines.

This property makes it simple to manufacture a hyperbolic paraboloid from a variety of materials and for a variety of purposes, from concrete roofs to snack foods. In particular, Pringles fried snacks resemble a truncated hyperbolic paraboloid.

A hyperbolic paraboloid is a saddle surface, as its Gauss curvature is negative at every point. Therefore, although it is a ruled surface, it is not developable.

From the point of view of projective geometry, a hyperbolic paraboloid is one-sheet hyperboloid that is tangent to the plane at infinity.

A hyperbolic paraboloid of equation or (this is the same up to a rotation of axes) may be called a rectangular hyperbolic paraboloid, by analogy with rectangular hyperbolas.

- Plane sections

A plane section of a hyperbolic paraboloid with equation can be

- a line, if the plane is parallel to the z-axis, and has an equation of the form ,

- a parabola, if the plane is parallel to the z-axis, and the section is not a line,

- a pair of intersecting lines, if the plane is a tangent plane,

- a hyperbola, otherwise.

Examples in architecture

Saddle roofs are often hyperbolic paraboloids as they are easily constructed from straight sections of material. Some examples:

- Philips Pavilion Expo '58, Brussels (1958)

- IIT Delhi - Dogra Hall Roof

- St. Mary's Cathedral, Tokyo, Japan (1964)

- St Richard's Church, Ham, in Ham, London, England (1966)

- Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption, San Francisco, California, US (1971)

- Saddledome in Calgary, Alberta, Canada (1983)

- Scandinavium in Gothenburg, Sweden (1971)

- L'Oceanogràfic in Valencia, Spain (2003)

- London Velopark, England (2011)

- Waterworld Leisure & Activity Centre, Wrexham, Wales (1970)

- Markham Moor Service Station roof, A1(southbound), Nottinghamshire, England

- Cafe "Kometa", Sokol district, Moscow, Russia (1960). Architect V.Volodin, engineer N.Drozdov. Demolished.

-

Warszawa Ochota railway station, an example of a hyperbolic paraboloid structure

Warszawa Ochota railway station, an example of a hyperbolic paraboloid structure

-

Surface illustrating a hyperbolic paraboloid

Surface illustrating a hyperbolic paraboloid

-

Restaurante Los Manantiales, Xochimilco, Mexico

Restaurante Los Manantiales, Xochimilco, Mexico

-

Hyperbolic paraboloid thin-shell roofs at L'Oceanogràfic, Valencia, Spain (taken 2019)

Hyperbolic paraboloid thin-shell roofs at L'Oceanogràfic, Valencia, Spain (taken 2019)

-

Markham Moor Service Station roof, Nottinghamshire (2009 photo)

Markham Moor Service Station roof, Nottinghamshire (2009 photo)

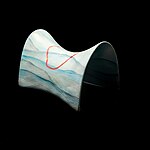

Cylinder between pencils of elliptic and hyperbolic paraboloids

The pencil of elliptic paraboloids and the pencil of hyperbolic paraboloids approach the same surface for , which is a parabolic cylinder (see image).

Curvature

The elliptic paraboloid, parametrized simply as has Gaussian curvature and mean curvature which are both always positive, have their maximum at the origin, become smaller as a point on the surface moves further away from the origin, and tend asymptotically to zero as the said point moves infinitely away from the origin.

The hyperbolic paraboloid, when parametrized as has Gaussian curvature and mean curvature

Geometric representation of multiplication table

If the hyperbolic paraboloid is rotated by an angle of π/4 in the +z direction (according to the right hand rule), the result is the surface and if a = b then this simplifies to Finally, letting a = √2, we see that the hyperbolic paraboloid is congruent to the surface which can be thought of as the geometric representation (a three-dimensional nomograph, as it were) of a multiplication table.

The two paraboloidal R → R functions and are harmonic conjugates, and together form the analytic function which is the analytic continuation of the R → R parabolic function f(x) = x/2.

Dimensions of a paraboloidal dish

The dimensions of a symmetrical paraboloidal dish are related by the equation where F is the focal length, D is the depth of the dish (measured along the axis of symmetry from the vertex to the plane of the rim), and R is the radius of the rim. They must all be in the same unit of length. If two of these three lengths are known, this equation can be used to calculate the third.

A more complex calculation is needed to find the diameter of the dish measured along its surface. This is sometimes called the "linear diameter", and equals the diameter of a flat, circular sheet of material, usually metal, which is the right size to be cut and bent to make the dish. Two intermediate results are useful in the calculation: P = 2F (or the equivalent: P = R/2D) and Q = √P + R, where F, D, and R are defined as above. The diameter of the dish, measured along the surface, is then given by where ln x means the natural logarithm of x, i.e. its logarithm to base e.

The volume of the dish, the amount of liquid it could hold if the rim were horizontal and the vertex at the bottom (e.g. the capacity of a paraboloidal wok), is given by where the symbols are defined as above. This can be compared with the formulae for the volumes of a cylinder (πRD), a hemisphere (2π/3RD, where D = R), and a cone (π/3RD). πR is the aperture area of the dish, the area enclosed by the rim, which is proportional to the amount of sunlight a reflector dish can intercept. The surface area of a parabolic dish can be found using the area formula for a surface of revolution which gives

See also

- Ellipsoid – Quadric surface that looks like a deformed sphere

- Hyperboloid – Unbounded quadric surface

- Parabolic loudspeaker – Parabolic-shaped speaker producing coherent plane waves

- Parabolic reflector – Reflector that has the shape of a paraboloid

References

- Thomas, George B.; Maurice D. Weir; Joel Hass; Frank R. Giordiano (2005). Thomas' Calculus 11th ed. Pearson Education, Inc. p. 892. ISBN 0-321-18558-7.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Hyperbolic Paraboloid." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/HyperbolicParaboloid.html

- Thomas, George B.; Maurice D. Weir; Joel Hass; Frank R. Giordiano (2005). Thomas' Calculus 11th ed. Pearson Education, Inc. p. 896. ISBN 0-321-18558-7.

- Zill, Dennis G.; Wright, Warren S. (2011), Calculus: Early Transcendentals, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, p. 649, ISBN 9781449644482.

External links

- [REDACTED] Media related to Paraboloid at Wikimedia Commons

where a and b are constants that dictate the level of curvature in the xz and yz planes respectively. In this position, the elliptic paraboloid opens upward.

where a and b are constants that dictate the level of curvature in the xz and yz planes respectively. In this position, the elliptic paraboloid opens upward.

In this position, the hyperbolic paraboloid opens downward along the x-axis and upward along the y-axis (that is, the parabola in the plane x = 0 opens upward and the parabola in the plane y = 0 opens downward).

In this position, the hyperbolic paraboloid opens downward along the x-axis and upward along the y-axis (that is, the parabola in the plane x = 0 opens upward and the parabola in the plane y = 0 opens downward).

or

or  (this is the same

(this is the same  can be

can be

,

, and the pencil of hyperbolic paraboloids

and the pencil of hyperbolic paraboloids

approach the same surface

approach the same surface

for

for  ,

which is a parabolic cylinder (see image).

,

which is a parabolic cylinder (see image).

has

has  and

and  which are both always positive, have their maximum at the origin, become smaller as a point on the surface moves further away from the origin, and tend asymptotically to zero as the said point moves infinitely away from the origin.

which are both always positive, have their maximum at the origin, become smaller as a point on the surface moves further away from the origin, and tend asymptotically to zero as the said point moves infinitely away from the origin.

has Gaussian curvature

has Gaussian curvature

and mean curvature

and mean curvature

and if a = b then this simplifies to

and if a = b then this simplifies to

Finally, letting a = √2, we see that the hyperbolic paraboloid

Finally, letting a = √2, we see that the hyperbolic paraboloid

is congruent to the surface

is congruent to the surface

which can be thought of as the geometric representation (a three-dimensional

which can be thought of as the geometric representation (a three-dimensional  and

and

are

are  which is the

which is the  where F is the focal length, D is the depth of the dish (measured along the axis of symmetry from the vertex to the plane of the rim), and R is the radius of the rim. They must all be in the same

where F is the focal length, D is the depth of the dish (measured along the axis of symmetry from the vertex to the plane of the rim), and R is the radius of the rim. They must all be in the same  where ln x means the

where ln x means the  where the symbols are defined as above. This can be compared with the formulae for the volumes of a

where the symbols are defined as above. This can be compared with the formulae for the volumes of a