De Oratore (On the Orator) is a dialogue written by Cicero in 55 BC. It is set in 91 BC, when Lucius Licinius Crassus dies, just before the Social War and the civil war between Marius and Sulla, during which Marcus Antonius, the other great orator of this dialogue, dies. During this year, the author faces a difficult political situation: after his return from exile in Dyrrachium (modern Albania), his house was destroyed by the gangs of Clodius in a time when violence was common. This was intertwined with the street politics of Rome.

Amidst the moral and political decadence of the state, Cicero wrote De Oratore to describe the ideal orator and imagine him as a moral guide of the state. He did not intend De Oratore as merely a treatise on rhetoric, but went beyond mere technique to make several references to philosophical principles. Cicero believed that the power of persuasion—the ability to verbally manipulate opinion in crucial political decisions—was a key issue and that in the hands of an unprincipled orator, this power would endanger the entire community.

As a consequence, moral principles can be taken either by the examples of noble men of the past or by the great Greek philosophers, who provided ethical ways to be followed in their teaching and their works. The perfect orator shall be not merely a skilled speaker without moral principles, but both an expert of rhetorical technique and a man of wide knowledge in law, history, and ethical principles. De Oratore is an exposition of issues, techniques, and divisions in rhetoric; it is also a parade of examples for several of them and it makes continuous references to philosophical concepts to be merged for a perfect result.

Choice of the historical background of the dialogue

At the time when Cicero wrote the dialogue, the crisis of the state concerned everyone. The dialogue deliberately clashes with the quiet atmosphere of the villa in Tusculum. Cicero tries to reproduce the feeling of the final peaceful days in the old Roman republic.

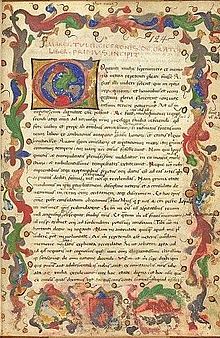

Despite De Oratore (On the Orator) being a discourse on rhetoric, Cicero has the original idea of inspiring himself to Plato's Dialogues, replacing the streets and squares of Athens with a nice garden of a country villa of a noble Roman aristocrat. With this fanciful device, he avoided the arid explanation of rhetoric rules and devices. The work contains the second known description of the method of loci, a mnemonic technique (after the Rhetorica ad Herennium).

Book I

Introduction

- Cicero begins his book by addressing this as a conversation to his brother. He continues on reflecting about so little time left in his life to be dedicated to noble studies.

Unfortunately, the deep crisis of the state (the civil war between Marius and Sulla, the conjuration of Catilina and the first triumvirate, that excluded him from the active political life) has wasted away his best years.

Education of the orator

- Cicero explains that he wants to write something more refined and mature than what he had previously published in his younger and more immature days in his treatise De Inventione.

Several eminent men in all fields, except oratory

- Cicero questions why, despite the fact that many people have exceptional abilities, there are so few exceptional orators.

Many are the examples of war leaders, and will continue to be throughout history, but only a handful of great orators. - Countless men have become eminent in philosophy, because they have studied the matter thoroughly, either by scientific investigation or using dialectic methods.

Each philosopher has become excellent in his individual field, which includes oratory.

Nevertheless, the study of oratory has attracted the smallest number of distinguished men, even less than poetry.

Cicero finds this amazing, as the other arts are usually found in hidden or remote sources;

on the contrary, all of oratory is public and in plain view to mankind, making it easier to learn.

Oratory is an attractive but difficult study

- Cicero claims that in Athens, "where the supreme power of oratory was both invented and perfected," no other art study has a more vigorous life than the art of speaking.

After Roman peace had been established, it seemed as though everyone wanted to begin learning the eloquence of oral rhetoric.

After first trying rhetoric without training or rules, using only natural skill, young orators listened and learned from Greek orators and teachers, and soon were much more enthusiastic for eloquence. Young orators learned, through practice, the importance of variety and frequency of speech. In the end, orators were awarded with popularity, wealth, and reputation.

- But Cicero warns that oratory fits into more arts and areas of study than people might think.

This is the reason why this particular subject is such a difficult one to pursue.

- Students of oratory must have a knowledge of many matters to have successful rhetoric.

- They must also form a certain style through word choice and arrangement. Students must also learn to understand human emotion so as to appeal to their audience.

This means that the student must, through his style, bring in humor and charm—as well as the readiness to deliver and respond to an attack.

- Moreover, a student must have a significant capacity for memory—they must remember complete histories of the past, as well as of the law.

- Cicero reminds us of another difficult skill required for a good orator: a speaker must deliver with control—using gestures, playing and expressing with features, and changing the intonation of the voice.

In summary, oratory is a combination of many things, and to succeed in maintaining all of these qualities is a great achievement. This section marks Cicero's standard canons for the rhetorical composing process.

Responsibility of the orator; argument of the work

- Orators must have a knowledge in all important subjects and arts. Without this, his speech would be empty, without beauty and fullness.

The term "orator" in itself holds a responsibility for the person to profess eloquence, in such a way that he should be able to treat every subject with distinction and knowledge.

Cicero acknowledges that this is a practically impossible task, nevertheless it is at least a moral duty for the orator.

The Greeks, after dividing the arts, paid more attention to the portion of oratory that is concerned with the law, courts, and debate, and therefore left these subjects for orators in Rome.

Indeed, all that the Greeks have written in their treaties of eloquence or taught by the masters thereof, but Cicero prefers to report the moral authority of these Roman orators.

Cicero announces that he will not expose a series of prescriptions but some principles, that he learnt to have been discussed once by excellent Roman orators.

Date, scene, and persons

Cicero exposes a dialogue, reported to him by Cotta, among a group of excellent political men and orators, who came together to discuss the crisis and general decline of politics. They met in the garden of Lucius Licinius Crassus' villa in Tusculum, during the tribunate of Marcus Livius Drusus (91 BCE). Thereto also gathered Lucius Licinius Crassus, Quintus Mucius Scaevola, Marcus Antonius, Gaius Aurelius Cotta and Publius Sulpicius Rufus. One member, Scaevola, wants to imitate Socrates as he appears in Plato's Phaedrus. Crassus replies that, instead, they will find a better solution, and calls for cushions so that this group can discuss it more comfortably.

Thesis: the importance of oratory to society and the state

Crassus states that oratory is one of the greatest accomplishments that a nation can have.

He extols the power that oratory can give to a person, including the ability to maintain personal rights, words to defend oneself, and the ability to revenge oneself on a wicked person.

The ability to converse is what gives mankind our advantage over other animals and nature. It is what creates civilization. Since speech is so important, why should we not use it to the benefit of oneself, other individuals, and even the entire State?

- Thesis challenged

Scaevola agrees with Crassus's points except for two.

Scaevola does not feel that orators are what created social communities and he questions the superiority of the orator if there were no assemblies, courts, etc.

It was good decision making and laws that formed society, not eloquence. Was Romulus an orator? Scaevola says that there are more examples of damage done by orators than good, and he could cite many instances.

There are other factors of civilization that are more important than orator: ancient ordinances, traditions, augury, religious rites and laws, private individual laws.

Had Scaevola not been in Crassus's domain, Scaevola would take Crassus to court and argue over his assertions, a place where oratory belongs.

Courts, assemblies and the Senate are where oratory should remain, and Crassus should not extend the scope of oratory beyond these places. That is too sweeping for the profession of oratory.

- Reply to challenge

Crassus replies that he has heard Scaevola's views before, in many works including Plato's Gorgias. However, he does not agree with their viewpoint. In respects to Gorgias, Crassus reminds that, while Plato was making fun of orators, Plato himself was the ultimate orator. If the orator was nothing more than a speaker without the knowledge of oratory, how is it possible that the most revered people are skilled orators? The best speakers are those who have a certain "style", which is lost, if the speaker does not comprehend the subject matter on which he is speaking.

Rhetoric is a science

Crassus says he does not borrow from Aristotle or Theophrastus their theories regarding the orator. For while the schools of Philosophy claim that rhetoric and other arts belong to them, the science of oratory which adds "style," belong to its own science. Lycurgus, Solon were certainly more qualified about laws, war, peace, allies, taxes, civil right than Hyperides or Demosthenes, greater in the art of speaking in public. Similarly in Rome, the decemviri legibus scribundis were more expert in right than Servius Galba and Gaius Lelius, excellent Roman orators. Nevertheless, Crassus maintains his opinion that "oratorem plenum atque perfectum esse eum, qui de omnibus rebus possit copiose varieque dicere". (the complete and perfect orator is him who can speak in public about every subject with richness of arguments and variety of tunes and images).

The orator must know the facts

To speak effectively, the orator must have some knowledge of the subject.

Can an advocate for or against war speak on the subject without knowing the art of war? Can an advocate speak on legislation if he does not know law or how the administration process works?

Even though others will disagree, Crassus states that an expert of the natural science also must use oratory style to give an effective speech on his subject.

For example, Asclepiades, a well-known physician, was popular not just because of his medical expertise, but because he could share it with eloquence.

The orator can have technical skills, but must be versed in moral science

Anyone who can speak with knowledge upon a subject, can be called an orator as long as he does so with knowledge, charm, memory and has a certain style.

Philosophy is divided into three branches: natural studies, dialectic and knowledge of human conduct (in vitam atque mores). To truly be a great orator, one must master the third branch: this is what distinguishes the great orator.

The orator, like the poet, needs a wide education

Cicero mentions Aratos of Soli, not expert in astronomy, and yet he wrote a marvellous poem (Phaenomena). So did Nicander of Colophon, who wrote excellent poems on agriculture (Georgika).

An orator is very much like the poet. The poet is more encumbered by rhythm than the orator, but richer in word choice and similar in ornamentation.

Crassus then replies to Scaevola's remark: he would not have claimed that orators should be experts in all subjects, should he himself be the person he is describing.

Nevertheless, everyone can easily understand, in the speeches before assemblies, courts or before the Senate, if a speaker has good exercise in the art of speaking in public or if he is also well educated in eloquence and all the liberal arts.

Scaevola, Crassus and Antonius debate on the orator

- Scaevola says he will debate with Crassus no longer, because he was able to twist some of what he has said to his own benefit.

Scaevola appreciates that Crassus, unlike some others, did not jeer at philosophy and the other arts; instead, he gave them credit and put them under the category of oratory.

Scaevola cannot deny that a man who had mastered all the arts, and was also a powerful speaker, would indeed be a remarkable man. And if there ever were such a man, it would be Crassus. - Crassus again denies that he is this kind of man: he is talking about an ideal orator.

However, if others think so, what then would they think of a person who will show greater skills and will be really an orator? - Antonius approves all what Crassus said. But to become a great orator by Crassus's definition would be difficult.

First, how would a person get knowledge of every subject? Second, it would be hard for this person to stay strictly true to traditional oratory and not be led astray into advocacy. Antonius ran into this himself while delayed in Athens. Rumor got out that he was a "learned man", and he was approached by many people to discuss with him, according to each one's capabilities, on the duties and the method of the orator.

A reported debate at Athens

Antonius tells of the debate that occurred in Athens regarding this very subject.

- Menedemus said that there is a science of the fundamentals of foundation and government of the state.

- On the other side, Charmadas replied that this is found in philosophy.

He thought that the books of rhetoric do not teach knowledge of the gods, the education of young people, justice, tenacy and self-control, moderation in every situation.

Without all those things, no state can exist nor be well ordered.

By the way, he wondered why the masters of rhetoric, in their books, did not write a single word on the constitution of the states, on how to write a law, about equality, about justice, loyalty, on retaining desires or the building of human character.

They have built up with their art such a plenty of very important arguments, with books full of prooemiums, epilogues and similar trivial things - he used exactly this term.

Because of this, Charmadas was used to mock their teachings, saying that they were not only the competence they claimed, but also they did not know the method of eloquence.

Indeed, he stated that a good orator must shine of a good light himself, that is by his dignity of life, about which nothing is said by those masters of rhetoric.

Moreover, the audience is directed into the mood, in which the orator drives them. But this can not happen, if he does not know in how many and in which ways he can drive the feelings of the men.

This is because these secrets are hidden in the deepest heart of philosophy and the rhetors have never even touched it in its surface.

- Menedemus rebutted Charmadas by quoting passages from the speeches of Demosthenes. And he gave examples of how speeches given from the knowledge of law and politics can compel the audience.

- Charmadas agrees that Demosthenes was a good orator, but questions whether this was a natural ability or because of his studies of Plato.

Demosthenes often said that there was no art to eloquence—but there is a natural aptitude, that makes us able to blandish and beg someone, to threaten rivals, to expose a fact and reinforce our thesis with arguments, refuting the other's ones.

In a nutshell, Antonius thought Demosthenes appeared to be arguing that there was no "craft" of oratory and no one could speak well unless he had mastered philosophical teaching.

- Charmadas, finally stated that Antonius was a very docile listener, Crassus was a fighting debater.

Difference between disertus and eloquens

Antonius, convinced by those arguments, says he wrote a pamphlet about them.

He names disertus (easy-speaking), a person who can speak with sufficient clearness and smartness, before people of medium level, about whichever subject;

on the other hand he names eloquens (eloquent) a person, who is able to speak in public, using nobler and more adorned language on whichever subject, so that he can embrace all sources of the art of eloquence with his mind and memory.

Someday, somewhere a man will come along who will not just claim to be eloquent, but will actually be truly eloquent. And if this man is not Crassus, then he can only be a little bit better than Crassus.

Sulpicius is gleeful that, as he and Cotta had hoped, someone would mention Antonius and Crassus in their conversations so that they could get some glimmer of knowledge from these two respected individuals. Since Crassus started the discussion, Sulpicius asks him to give his views on oratory first. Crassus replies that he would rather have Antonius speak first as he himself tends to shy away from any discourse on this subject. Cotta is pleased that Crassus has responded in any way because it is usually so difficult to get him to respond in any manner about these matters. Crassus agrees to answer any questions from Cotta or Sulpicius, as long as they are within his knowledge or power.

Is there a science of rhetoric?

Sulpicius asks, "is there an 'art' of oratory?" Crassus responds with some contempt. Do they think he is some idle talkative Greekling? Do they think that he just answers any question that is posed to him? It was Gorgias that started this practice—which was great when he did it—but is so overused today that there is no topic, however grand, that some people claim they cannot respond to. Had he known this was what Sulpius and Cotta wanted, he would have brought a simple Greek with him to respond—which he still can do if they want him to.

Mucius chides Crassus. Crassus agreed to answer the young men's questions, not to bring in some unpracticed Greek or another to respond. Crassus has been known for being a kind person, and it would be becoming for him to respect their question, to answer it, and not run away from responding.

Crassus agrees to answer their question. No, he says. There is no art of speaking, and if there is an art to it, it is a very thin one, as this is just a word. As Antonius had previously explained, an Art is something that has been thoroughly looked at, examined and understood. It is something that is not an opinion, but is an exact fact. Oratory cannot possibly fit into this category. However, if the practices of oratory and how oratory is conducted is studied, put into terms and classification, this could then—possibly—be considered to be an art.

Crassus and Antonius debate on the orator's natural talent

- Crassus says that natural talent and mind are the key factors to be a good orator.

Using Antonius's example earlier, these people didn't lack the knowledge of oratory, they lacked the innate ability.

- The orator shall have by nature not only heart and mind, but also speedy moves both to find brilliant arguments and to enrich them with development and ornate, constant and tight to keep them in memory.

- Does anybody think really that these abilities can be gained by an art?

No, they are gifts of nature, that is the ability to invent, richness in talking, strong lungs, certain voice tones, particular body physique as well as a pleasant looking face.

- Crassus does not deny that rhetoric technique can improve the qualities of orators; on the other hand, there are people with so deep lacks in the just cited qualities, that, despite every effort, they will not succeed.

- It is a really heavy task to be the very one man speaking, on the most important issues and in a crowded assembly, while everyone keeps silent and pays more attention to the defects than the merits of the speaker himself.

- Should he say something unpleasant, this would cancel also all the pleasant he said.

- Anyway, this is not intended to make the young people go away from the interest in oratory,

provided that they have natural gifts for it: everyone can see the good example of Gaius Celius and Quintus Varius, who gained the people's favour by their natural ability in oratory. - However, since the objective is to look for The Perfect Orator, we must imagine one who has all the necessary traits without any flaws. Ironically, since there is such a variety of lawsuits in the courts, people will listen to even the worst lawyer's speeches, something we would not put up with in the theatre.

- And now, Crassus states, he will finally speak about that which he has always kept silent. The better the orator is, the more shame, nervous and doubtful he will feel about his speeches. Those orators that are shameless should be punished. Crassus himself declares that he is scared to death before every speech.

Because of his modesty in this speech, the others in the group elevate Crassus in status even higher.

- Antonius replies that he has noticed this sacredness in Crassus and other really good orators.

- This is because really good orators know that, sometimes, the speech does not have the intended effect that the speaker wished it to have.

- Also, orators tend to be judged harsher than others, as they are required to know so much about so many topics.

An orator is easily set-up by the very nature of what he does to be labeled ignorant.

- Antonius completely agrees that an orator must have natural gifts and no master can teach him them. He appreciates Apollonius of Alabanda, a great master of rhetoric, who refused to continue teaching to those pupils he did not find able to become great orators.

If one studies other disciplines, he simply needs to be an ordinary man.

- But for an orator, there are so many requirements such as the subtility of a logician, the mind of a philosopher, the language of a poet, the memory of a lawyer, the voice of a tragic actor and the gesture of the most skilled actor.

- Crassus finally considers how little attention is paid in learning the art of oratory versus other arts.

Roscius, a famous actor, often complained that he hadn't found a pupil who deserved his approval. There were many with good qualities, but he could not tolerate any fault in them. If we consider this actor, we can see that he makes no gesture of absolute perfection, of highest grace, exactly to give the public emotion and pleasure. In so many years, he reached such a level of perfection, that everyone, who distinguishes himself in a particular art, is called a Roscius in his field. The man who does not have the natural ability for oratory, he should instead try to achieve something that is more within his grasp.

Crassus replies to some objections by Cotta and Sulpicius

Sulpicius asks Crassus if he is advising Cotta and him to give up with oratory and rather to study civil right or to follow a military career. Crassus explains that his words are addressed to other young people, who have not the natural talent for oratory, rather than discourage Sulpicius and Cotta, who have great talent and passion for it.

Cotta replies that, given that Crassus stimulates them to dedicate themselves to oratory, now it is time to reveal the secret of his excellence in oratory. Moreover, Cotta wishes to know which other talents they have still to reach, apart those natural, which they have—according to Crassus.

Crassus says that this is quite an easy task, since he asks him to tell about his own oratory ability, and not about the art of oratory in general. Therefore, he will expose his usual method, which he used once when he was young, not anything strange or mysterious nor difficult nor solemn.

Sulpicius exults: "At last the day we desired so much, Cotta, has come! We will be able to listen from his very words the way he elaborates and prepares his speeches".

Fundamentals of rhetoric

"I will not tell you anything really mysterious", Crassus says the two listeners. First is a liberal education and follow the lessons that are taught in these classes. The main task of an orator is to speak in a proper way to persuade the audience; second, each speech can be on a general matter, without citing persons and dates, or a specific one, regarding particular persons and circumstances. In both cases, it is usual to ask:

- if the fact has happened and, if so,

- which is its nature

- how can it be defined

- if it is legal or not.

There are three kind of speeches: first, those in the courts, those in public assemblies, and those that praise or blame someone.

There are also some topics (loci) to be used in trials, whose aim is justice; other ones to be used in assemblies, whose aim is give opinions; other ones to be used in laudatory speeches, whose aim is to celebrate the cited person.

All energy and ability of the orator must apply to five steps:

- find the arguments (inventio)

- dispose them in logical order, by importance and opportunity (dispositio)

- ornate the speech with devices of the rhetoric style (elocutio)

- retain them in memory (memoria)

- expose the speech with art of grace, dignity, gesture, modulation of voice and face (actio).

Before pronouncing the speech, it is necessary to gain the goodwill of the audience; then expose the argument; after, establish the dispute; subsequently, show evidence of one's own thesis; then, rebut the other party's arguments; finally, remark our strong positions and weaken the other's.

As regards the ornaments of style, first one is taught to speak with pure and Latin language (ut pure et Latine loquamur); second to express oneself clearly; third to speak with elegance and corresponding to the dignity of the arguments and conveniently. The rhetors' rules are useful means for the orator. The fact is, however, that these rules came out by the observation of some people on the natural gift of others. That is, it is not the eloquence that is born from rhetoric, but the rhetoric is born by eloquence. I do not refuse rhetoric, although I believe it is not indispensable for the orator.

Then Sulpicius says: "That is what we want to better know! The rhetoric rules that you mentioned, even if they are not so now for us. But this later; now we want your opinion about exercises".

The exercise (exercitatio)

Crassus approves the practice of speaking, imaging to be treating a trial in a court. However, this has the limit of exercising the voice, not yet with art, or its power, increasing the speed of speaking and the richness of vocabulary; therefore, one is alluded to have learnt to speak in public.

- On the contrary, the most important exercise, that we usually avoid because it is the most tiring, it is to write speeches as much as possible.

Stilus optimus et praestantissimus dicendi effector ac magister (The pen is the best and most efficient creator and master of speaking). Like an improvised speech is lower than a well thought one, so this one is, compared to a well prepared and built writing. All arguments, either those of rhetoric and from one's nature and experience, come out by themselves. But the most striking thoughts and expressions come one after the other by the style; so the harmonic placing and disposing words is acquired by writing with oratory and not poetic rhythm (non poetico sed quodam oratorio numero et modo).

- The approval towards an orator can be gained only after having written speeches very long and much; this is much more important than physical exercise with the greatest effort.

In addition, the orator, who is used to write speeches, reaches the aim that, even in an improvised speech, he seems to speak so similar to a written text.

Crassus remembers some of his exercises when he was younger, he began to read and then imitate poetry or solemn speeches. This was a used exercise of his main adversary, Gaius Carbo. But after a while, he found that this was an error, because he did not gain benefit imitating the verses of Ennius or the speeches of Gracchus.

- So he began to translate Greek speeches into Latin. This led to finding better words to use in his speeches as well as providing new neologisms that would appeal to the audience.

- As for the proper voice control, one should study good actors, not just orators.

- Train one's memory by learning as many written works as possible (ediscendum ad verbum).

- One should also read the poets, know the history, read and study authors of all disciplines, criticize and refute all opinions, taking all likely arguments.

- It is necessary to study the civil right, know the laws and the past, that is rules and traditions of the state, the constitution, the rights of the allies and the treaties.

- Finally, as an added measure, shed a bit of fine humor on the speech, like the salt on the food.

Everyone is silent. Then Scaevola asks if Cotta or Sulpicius have any more questions for Crassus.

Debate on Crassus' opinions

Cotta replies that Crassus' speech was so raging that he could not catch his content completely. It was like he entered in a rich house, full of rich carpets and treasures, but piled in disorder and not in full view or hidden. "Why do not you ask Crassus," Scaevola says to Cotta, "to place his treasures in order and in full view?" Cotta hesitates, but Mucius asks again Crassus to expose in detail his opinion about the perfect orator.

Crassus gives examples of orators not expert in civil right

Crassus first hesitates, saying that he does not know some disciplines as much as a master. Scaevola then encourages him to expose his notions, so fundamental for the perfect orator: on the nature of men, on their attitudes, on the methods by which one excites or calms their souls; notions of history, of antiquities, of State administration and of civil right. Scaevola knows well that Crassus has a wise knowledge of all these matters and he is also an excellent orator.

Crassus begins his speech underlining the importance of studying civil right. He quotes the case of two orators, Ipseus and Cneus Octavius, which brought a lawsuit with great eloquence, but lacking of any knowledge of civil right. They committed great gaffes, proposing requests in favour of their client, which could not fit the rules of civil right.

Another case was the one of Quintus Pompeius, who, asking damages for a client of his, committed a formal, little error, but such that it endangered all his court action. Finally Crassus quotes positively Marcus Porcius Cato, who was at the top of eloquence, at his times, and also was the best expert in civil right, although he said he despised it.

As regards Antonius, Crassus says he has such a talent for oratory, so unique and incredible, that he can defend himself with all his devices, gained by his experience, although he lacks of knowledge of civil right. On the contrary, Crassus condemns all the others, because they are lazy in studying civil right, and yet they are so insolent, pretending to have a wide culture; instead, they fall miserably in private trials of little importance, because they have no experience in detailed parts of civil right .

Studying civil right is important

Crassus continues his speech, blaming those orators who are lazy in studying civil right. Even if the study of law is wide and difficult, the advantages that it gives deserve this effort. Notwithstanding the formulae of Roman civil right have been published by Gneus Flavius, no one has still disposed them in systematic order.

Even in other disciplines, the knowledge has been systematically organised; even oratory made the division on a speech into inventio, elocutio, dispositio, memoria and actio. In civil right there is need to keep justice based on law and tradition. Then it is necessary to depart the genders and reduce them to a reduce number, and so on: division in species and definitions.

Gaius Aculeo has a secure knowledge of civil right in such a way that only Scaevola is better than he is. Civil right is so important that - Crassus says - even politics is contained in the XII Tabulae and even philosophy has its sources in civil right. Indeed, only laws teach that everyone must, first of all, seek good reputation by the others (dignitas), virtue and right and honest labour are decked of honours (honoribus, praemiis, splendore). Laws are fit to dominate greed and to protect property.

Crassus then believes that the libellus XII Tabularum has more auctoritas and utilitas than all others works of philosophers, for those who study sources and principles of laws. If we have to love our country, we must first know its spirit (mens), traditions (mos), constitution (disciplines), because our country is the mother of all of us; this is why it was so wise in writing laws as much as building an empire of such a great power. The Roman right is well more advanced than that of other people, including the Greek.

Crassus' final praise of studying civil right

Crassus once more remarks how much honour gives the knowledge of civil right. Indeed, unlike the Greek orators, who need the assistance of some expert of right, called pragmatikoi, the Roman have so many persons who gained high reputation and prestige on giving their advice on legal questions. Which more honourable refuge can be imagined for the older age than dedicating oneself to the study of right and enrich it by this? The house of the expert of right (iuris consultus) is the oracle of the entire community: this is confirmed by Quintus Mucius, who, despite his fragile health and very old age, is consulted every day by a large number of citizens and by the most influent and important persons in Rome.

Given that—Crassus continues—there is no need to further explain how much important is for the orator to know public right, which relates to government of the state and of the empire, historical documents and glorious facts of the past. We are not seeking a person who simply shouts before a court, but a devoted to this divine art, who can face the hits of the enemies, whose word is able to raise the citizens' hate against a crime and the criminal, hold them tight with the fear of punishment and save the innocent persons by conviction. Again, he shall wake up tired, degenerated people and raise them to honour, divert them from the error or fire them against evil persons, calm them when they attack honest persons. If anyone believes that all this has been treated in a book of rhetoric, I disagree and I add that he neither realises that his opinion is completely wrong. All I tried to do, is to guide you to the sources of your desire of knowledge and on the right way.

Mucius praises Crassus and tells he did even too much to cope with their enthusiasm. Sulpicius agrees but adds that they want to know something more about the rules of the art of rhetoric; if Crassus tells more deeply about them, they will be fully satisfied. The young pupils there are eager to know the methods to apply.

What about—Crassus replies—if we ask Antonius now to expose what he keeps inside him and has not yet shown to us? He told that he regretted to let him escape a little handbook on the eloquence. The others agree and Crassus asks Antonius to expose his point of view.

Views of Antonius, gained from his experience

Antonius offers his perspective, pointing out that he will not speak about any art of oratory, that he never learnt, but on his own practical use in the law courts and from a brief treaty that he wrote.

He decides to begin his case the same way he would in court, which is to state clearly the subject for discussion.

In this way, the speaker cannot wander dispersedly and the issue is not understood by the disputants.

For example, if the subject were to decide what exactly is the art of being a general, then he would have to decide what a general does, determine who is a General and what that person does. Then he would give examples of generals, such as Scipio and Fabius Maximus and also Epaminondas and Hannibal.

And if he were defining what a statesman is, he would give a different definition, characteristics of men who fit this definition, and specific examples of men who are statesmen, he would mention Publius Lentulus, Tiberius Gracchus, Quintus Cecilius Metellus, Publius Cornelius Scipio, Gaius Lelius and many others, both Romans and foreign persons.

If he were defining an expert of laws and traditions (iuris consultus), he would mention Sextus Aelius, Manius Manilius and Publius Mucius.

The same would be done with musicians, poets, and those of lesser arts. The philosopher pretends to know everything about everything, but, nevertheless he gives himself a definition of a person trying to understand the essence of all human and divine things, their nature and causes; to know and respect all practices of right living.

Definition of orator, according to Antonius

Antonius disagrees with Crassus' definition of orator, because the last one claims that an orator should have a knowledge of all matters and disciplines. On the contrary, Antonius believes that an orator is a person, who is able to use graceful words to be listened to and proper arguments to generate persuasion in the ordinary court proceedings. He asks the orator to have a vigorous voice, a gentle gesture and a kind attitude. In Antonius' opinion, Crassus gave an improper field to the orator, even an unlimited scope of action: not the space of a court, but even the government of a state. And it seemed so strange that Scaevola approved that, despite he obtained consensus by the Senate, although having spoken in a very synthetic and poor way. A good senator does not become automatically a good orator and vice versa. These roles and skills are very far each from the other, independent and separate. Marcus Cato, Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius, Gaius Lelius, all eloquent persons, used very different means to ornate their speeches and the dignity of the state.

Neither nature nor any law or tradition prohibit that a man is skilled in more than one discipline. Therefore, if Pericles was, at the same time, the most eloquent and the most powerful politician in Athens, we cannot conclude that both these distinct qualities are necessary to the same person. If Publius Crassus was, at the same time, an excellent orator and an expert of right, not for this we can conclude that the knowledge of right is inside the abilities of the oratory. Indeed, when a person has a reputation in one art and then he learns well another, he seems that the second one is part of his first excellence. One could call poets those who are called physikoi by the Greeks, just because the Empedocles, the physicist, wrote an excellent poem. But the philosophers themselves, although claiming that they study everything, dare to say that geometry and music belong to the philosopher, just because Plato has been unanimously acknowledged excellent in these disciplines.

In conclusion, if we want to put all the disciplines as a necessary knowledge for the orator, Antonius disagrees, and prefers simply to say that the oratory needs not to be nude and without ornate; on the contrary, it needs to be flavoured and moved by a graceful and changing variety. A good orator needs to have listened a lot, watched a lot, reflecting a lot, thinking and reading, without claiming to possess notions, but just taking honourable inspiration by others' creations. Antonius finally acknowledges that an orator must be smart in discussing a court action and never appear as an inexperienced soldier nor a foreign person in an unknown territory.

Difference between an orator and a philosopher

Antonius disagrees with Crassus' opinion: an orator does not need to have enquired deeply the human soul, behaviour and motions—that is, study philosophy—to excite or calm the souls of the audience. Antonius admires those who dedicated their time to study philosophy nor despites them, the width of their culture and the importance of this discipline. Yet, he believes that it is enough for the Roman orator to have a general knowledge of human habits and not to speak about things that clash with their traditions. Which orator, to put the judge against his adversary, has been ever in trouble to ignore anger and other passions, and, instead, used the philosophers' arguments? Some of these latest ones claim that one's soul must be kept away from passions and say it is a crime to excite them in the judges' souls. Other philosophers, more tolerant and more practical, say that passions should be moderate and smooth. On the contrary, the orator picks all these passions of everyday life and amplifies them, making them greater and stronger. At the same time he praises and gives appeal to what is commonly pleasant and desirable. He does not want to appear the wise among the stupids: by that, he would seem unable and a Greek with a poor art; otherwise they would hate to be treated as stupid persons. Instead, he works on every feeling and thought, driving them so that he need not to discuss philosophers' questions. We need a very different kind of man, Crassus, we need an intelligent, smart man by his nature and experience, skilled in catching thoughts, feelings, opinions, hopes of his citizens and of those who want to persuade with his speech.

The orator shall feel the people pulse, whatever their kind, age, social class, investigate the feelings of those who is going to speak to. Let him keep the books of the philosophers for his relax or free time; the ideal state of Plato had concepts and ideals of justice very far from the common life. Would you claim, Crassus, that the virtue (virtus) become slave of the precept of these philosophers? No, it shall always be anyway free, even if the body is captured. Then, the Senate not only can but shall serve the people; and which philosopher would approve to serve the people, if the people themselves gave him the power to govern and guide them? .

Episodes of the past: Rutilius Rufus, Servius Galba, Cato and Crassus

Antonius then reports a past episode: Publius Rutilius Rufus blamed Crassus before the Senate spoke not only parum commode (in few adequate way), but also turpiter et flagitiose (shamefully and in scandalous way). Rutilius Rufus himself blamed also Servius Galba, because he used pathetical devices to excite compassion of the audience, when Lucius Scribonius sued him in a trial. In the same proceeding, Marcus Cato, his bitter and dogged enemy, made a hard speech against him, that after inserted in his Origines. He would be convicted, if he would not have used his sons to rise compassion. Rutilius strongly blamed such devices and, when he was sued in court, chose not to be defended by a great orator like Crassus. Rather, he preferred to expose simply the truth and he faced the cruel feeling of the judges without the protection of the oratory of Crassus.

The example of Socrates

Rutilius, a Roman and a consularis, wanted to imitate Socrates. He chose to speak himself for his defence, when he was on trial and convicted to death. He preferred not to ask mercy or to be an accused, but a teacher for his judges and even a master of them. When Lysias, an excellent orator, brought him a written speech to learn by heart, he read it and found it very good but added: "You seem to have brought to me elegant shoes from Sicyon, but they are not suited for a man": he meant that the written speech was brilliant and excellent for an orator, but not strong and suited for a man. After the judges condemned him, they asked him which punishment he would have believed suited for him and he replied to receive the highest honour and live for the rest of his life in the Pritaneus, at the state expenses. This increased the anger of the judges, who condemned him to death. Therefore, if this was the end of Socrates, how can we ask the philosophers the rules of eloquence?. I do not question whether philosophy is better or worse than oratory; I only consider that philosophy is different by eloquence and this last one can reach the perfection by itself.

Antonius: the orator need not a wide knowledge of right

Antonius understands that Crassus has made a passionate mention to the civil right, a grateful gift to Scaevola, who deserves it. As Crassus saw this discipline poor, he enriched it with ornate.

Antonius acknowledges his opinion and respect it, that is to give great relevance to the study of civil right, because it is important, it had always a very high honour and it is studied by the most eminent citizens of Rome.

But pay attention, Antonius says, not to give the right an ornate that is not its own. If you said that an expert of right (iuris consultus) is also an orator and, equally, an orator is also an expert of right, you would put at the same level and dignity two very bright disciplines.

Nevertheless, at the same time, you admit that an expert of right can be a person without the eloquence we are discussing on, and, the more, you acknowledge that there were many like this.

On the contrary, you claim that an orator cannot exist without having learnt civil right.

Therefore, in your opinion, an expert of right is no more than a skilled and smart handler of right; but given that an orator often deals with right during a legal action, you have placed the science of right nearby the eloquence, as a simple handmaiden that follows her proprietress.

You blame—Antonius continues—those advocates, who, although ignoring the fundamentals of right face legal proceedings, I can defend them, because they used a smart eloquence.

But I ask you, Antonius, which benefit would the orator have given to the science of right in these trials, given that the expert of right would have won, not thanks to his specific ability, but to another's, thanks to the eloquence.

I was told that Publius Crassus, when was candidate for Aedilis and Servius Galba, was a supporter of him, he was approached by a peasant for a consult.

After having a talk with Publius Crassus, the peasant had an opinion closer to the truth than to his interests.

Galba saw the peasant going away very sad and asked him why. After having known what he listened by Crassus, he blamed him; then Crassus replied that he was sure of his opinion by his competence on right.

And yet, Galba insisted with a kind but smart eloquence and Crassus could not face him: in conclusion, Crassus demonstrated that his opinion was well founded on the books of his brother Publius Micius and in the commentaries of Sextus Aelius, but at last he admitted that Galba's thesis looked acceptable and close to the truth .

There are several kinds of trials, in which the orator can ignore civil right or parts of it, on the contrary, there are others, in which he can easily find a man, who is expert of right and can support him. In my opinion, says Antonius to Crassus, you deserved well your votes by your sense of humour and graceful speaking, with your jokes, or mocking many examples from laws, consults of the Senate and from everyday speeches. You raised fun and happiness in the audience: I cannot see what has civil right to do with that. You used your extraordinary power of eloquence, with your great sense of humour and grace.

Antonius further critiques Crassus

Considering the allegation that the young do not learn oratory, despite, in your opinion, it is so easy, and watching those who boast to be a master of oratory, claiming that it is very difficult,

- you are contradictory, because you say it is an easy discipline, while you admit it is still not this way, but it will become such one day.

- Second, you say it is full of satisfaction: on the contrary everyone will let to you this pleasure and prefer to learn by heart the Teucer of Pacuvius than the leges Manilianae.

- Third, as for your love for the country, do not you realise that the ancient laws are lapsed by themselves for oldness or repealed by new ones?

- Fourth, you claim that, thanks to the civil right, honest men can be educated, because laws promise prices to virtues and punishments to crimes. I have always thought that, instead, virtue can be communicated to men, by education and persuasion and not by threatens, violence or terror.

- As for me, Crassus, let me treat trials, without having learnt civil right: I have never felt such a failure in the civil action, that I brought before the courts.

For ordinary and everyday situations, cannot we have a generic knowledge? Cannot we be taught about civil right, in so far as we feel not stranger in our country?

- Should a court action deal with a practical case, then we would obliged to learn a discipline so difficult and complicate; likewise, we should act in the same way, should we have a skilled knowledge of laws or opinions of experts of laws, provided that we have not already studied them by young.

Fundamentals of rhetorics according to Antonius

Shall I conclude that the knowledge of civil right is not at all useful for the orator?

- Absolutely not: no discipline is useless, particularly for who has to use arguments of eloquence with abundance.

But the notions that an orator needs are so many, that I am afraid he would be lost, wasting his energy in too many studies.

- Who can deny that an orator needs the gesture and the elegance of Roscius, when acting in the court?

Nonetheless, nobody would advice the young who study oratory to act like an actor.

- Is there anything more important for an orator than his voice?

Nonetheless, no practising orator would be advised by me to care about this voice like the Greek and the tragic actors, who repeat for years exercise of declamation, while seating; then, every day, they lay down and lift their voice steadily and, after having made their speech, they sit down and they recall it by the most sharp tone to the lowest, like they were entering again into themselves.

- But of all this gesture, we can learn a summary knowledge, without a systematic method and, apart gesture and voice that cannot be improvised nor taken by others in a moment, any notion of right can be gained by experts or by the books.

- Thus, in Greece, the most excellent orators, as they are not skilled in right, are helped by expert of right, the pragmatikoi.

The Romans behave much better, claiming that law and right were guaranteed by persons of authority and fame.

Old age does not require study of law

As for the old age, that you claim relieved by loneliness, thanks to the knowledge of civil right, who knows that a large sum of money will relieve it as well? Roscius loves to repeat that the more he will go on with the age the more he will slow down the accompaniment of a flute-player and will make more moderate his chanted parts. If he, who is bound by rhythm and meter, finds out a device to allow himself a bit of a rest in the old age, the easier will be for us not only to slow down the rhythm, but to change it completely. You, Crassus, certainly know how many and how various are the way of speaking,. Nonetheless, your present quietness and solemn eloquence is not at all less pleasant than your powerful energy and tension of your past. Many orators, such as Scipio and Laelius, which gained all results with a single tone, just a little bit elevated, without forcing their lungs or screaming like Servius Galba. Do you fear that you home will no longer be frequented by citizens? On the contrary I am waiting the loneliness of the old age like a quiet harbour: I think that free time is the sweetest comfort of the old age

General culture is sufficient

As regards the rest, I mean history, knowledge of public right, ancient traditions and samples, they are useful. If the young pupils wish to follow your invitation to read everything, to listen to everything and learn all liberal disciplines and reach a high cultural level, I will not stop them at all. I have only the feeling that they have not enough time to practice all that and it seems to me, Crassus, that you have put on these young men a heavy burden, even if maybe necessary to reach their objective. Indeed, both the exercises on some court topics and a deep and accurate reflexion, and your stilus (pen), that properly you defined the best teacher of eloquence, need much effort. Even comparing one's oration to another's and improvise a discussion on another's script, either to praise or to criticize it, to strengthen it or to refute it, need much effort both on memory and on imitation. This heavy requirements can discourage more than encourage persons and should more properly be applied to actors than to orators. Indeed, the audience listens to us, the orators, most of the time, even if we are hoarse, because the subject and the lawsuit captures the audience; on the contrary, if Roscius has a little bit of hoarse voice, he is booed. Eloquence has many devices, not only the hearing to keep the interest high and the pleasure and the appreciation.

Practical exercise is fundamental

Antonius agrees with Crassus for an orator, who is able to speak in such a way to persuade the audience, provided that he limits himself to the daily life and to the court, renouncing to other studies, although noble and honourable. Let him imitate Demosthenes, who compensated his handicaps by a strong passion, dedition and obstinate application to oratory. He was indeed stuttering, but through his exercise, he became able to speak much more clearly than anyone else. Besides, having a short breath, he trained himself to retain the breath, so that he could pronounce two elevations and two remissions of voice in the same sentence.

We shall incite the young to use all their efforts, but the other things that you put before, are not part of the duties and of the tasks of the orator. Crassus replied: "You believe that the orator, Antonius, is a simple man of the art; on the contrary, I believe that he, especially in our State, shall not be lacking of any equipment, I was imaging something greater. On the other hand, you restricted all the task of the orator within borders such limited and restricted, that you can more easily expose us the results of your studies on the orator's duties and on the precepts of his art. But I believe that you will do it tomorrow: this is enough for today and Scaevola too, who decided to go to his villa in Tusculum, will have a bit of a rest. Let us take care of our health as well". All agreed and they decided to adjourn the debate.

Book II

De Oratore Book II is the second part of De Oratore by Cicero. Much of Book II is dominated by Marcus Antonius. He shares with Lucius Crassus, Quintus Catulus, Gaius Julius Caesar Strabo, and Sulpicius his opinion on oratory as an art, eloquence, the orator's subject matter, invention, arrangement, and memory.

Oratory as an art

Antonius surmises "that oratory is no more than average when viewed as an art". Oratory cannot be fully considered an art because art operates through knowledge. In contrast, oratory is based upon opinions. Antonius asserts that oratory is "a subject that relies on falsehood, that seldom reaches the level of real knowledge, that is out to take advantage of people's opinions and often their delusions" (Cicero, 132). Still, oratory belongs in the realm of art to some extent because it requires a certain kind of knowledge to "manipulate human feelings" and "capture people's goodwill".

Eloquence

Antonius believes that nothing can surpass the perfect orator. Other arts do not require eloquence, but the art of oratory cannot function without it. Additionally, if those who perform any other type of art happen to be skilled in speaking it is because of the orator. But, the orator cannot obtain his oratorical skills from any other source.

The orator's subject matter

In this portion of Book II Antonius offers a detailed description of what tasks should be assigned to an orator. He revisits Crassus' understanding of the two issues that eloquence, and thus the orator, deals with. The first issue is indefinite while the other is specific. The indefinite issue pertains to general questions while the specific issue addresses particular persons and matters. Antonius begrudgingly adds a third genre of laudatory speeches. Within laudatory speeches it is necessary include the presence of “descent, money, relatives, friends, power, health, beauty, strength, intelligence, and everything else that is either a matter of the body or external" (Cicero, 136). If any of these qualities are absent then the orator should include how the person managed to succeed without them or how the person bore their loss with humility. Antonius also maintains that history is one of the greatest tasks for the orator because it requires a remarkable "fluency of diction and variety". Finally, an orator must master “everything that is relevant to the practices of citizens and the ways human behave” and be able to utilize this understanding of his people in his cases.

Invention

Antonius begins the section on invention by proclaiming the importance of an orator having a thorough understanding of his case. He faults those who do not obtain enough information about their cases, thereby making themselves look foolish. Antonius continues by discussing the steps that he takes after accepting a case. He considers two elements: "the first one recommends us or those for whom we are pleading, the second is aimed at moving the minds of our audience in the direction we want" (153). He then lists the three means of persuasion that are used in the art of oratory: "proving that our contentions are true, winning over our audience, and inducing their minds to feel any emotion the case may demand" (153). He discerns that determining what to say and then how to say it requires a talented orator. Also, Antonius introduces ethos and pathos as two other means of persuasion. Antonius believes that an audience can often be persuaded by the prestige or the reputation of a man. Furthermore, within the art of oratory it is critical that the orator appeal to the emotion of his audience. He insists that the orator will not move his audience unless he himself is moved. In his conclusion on invention Antonius shares his personal practices as an orator. He tells Sulpicius that when speaking his ultimate goal is to do good and if he is unable to procure some kind of good then he hopes to refrain from inflicting harm.

Arrangement

Antonius offers two principles for an orator when arranging material. The first principle is inherent in the case while the second principle is contingent on the judgment of the orator.

Memory

Antonius shares the story of Simonides of Ceos, the man whom he credits with introducing the art of memory. He then declares memory to be important to the orator because "only those with a powerful memory know what they are going to say, how far they will pursue it, how they will say it, which points they have already answered and which still remain" (220).

Book III

Further information: De Oratore, Book IIIDe Oratore, Book III is the third part of De Oratore by Cicero. It describes the death of Lucius Licinius Crassus.

They belong to the generation, which precedes the one of Cicero: the main characters of the dialogue are Marcus Antonius (not the triumvir) and Lucius Licinius Crassus (not the unofficial triumvir); other friends of them, such as Gaius Iulius Caesar (not the dictator), Sulpicius and Scaevola intervene occasionally.

At the beginning of the third book, which contains Crassus' exposition, Cicero is hit by a sad memory. He expresses all his pain to his brother Quintus Cicero. He reminds him that only nine days after the dialogue, described in this work, Crassus died suddenly. He came back to Rome the last day of the ludi scaenici (19 September 91 BC), very worried by the speech of the consul Lucius Marcius Philippus. He made a speech before the people, claiming the creation of a new council in place of the Roman Senate, with which he could not govern the State any longer. Crassus went to the curia (the palace of the Senate) and heard the speech of Drusus, reporting Lucius Marcius Philippus' speech and attacking him.

In that occasion, everyone agreed that Crassus, the best orator of all, overcame himself with his eloquence. He blamed the situation and the abandonment of the Senate: the consul, who should be his good father and faithful defender, was depriving it of its dignity like a robber. No need of surprise, indeed, if he wanted to deprive the State of the Senate, after having ruined the first one with his disastrous projects.

Philippus was a vigorous, eloquent and smart man: when he was attacked by the Crassus' firing words, he counter-attacked him until he made him keep silent. But Crassus replied:" You, who destroyed the authority of the Senate before the Roman people, do you really think to intimidate me? If you want to keep me silent, you have to cut my tongue. And even if you do it, my spirit of freedom will hold tight your arrogance".

Crassus' speech lasted a long time and he spent all of his spirit, his mind and his forces. Crassus' resolution was approved by the Senate, stating that "not the authority nor the loyalty of the Senate ever abandoned the Roman State". When he was speaking, he had a pain in his side and, after he came home, he got fever and died of pleurisy in six days.

"How insecure is the destiny of a man!", Cicero says. Just in the peak of his public career, Crassus reached the top of the authority, but also destroyed all his expectations and plans for the future by his death.

This sad episode caused pain, not only to Crassus' family, but also to all the honest citizens. Cicero adds that, in his opinion, the immortal gods gave Crassus his death as a gift, to preserve him from seeing the calamities that would befall the State a short time later. Indeed, he has not seen Italy burning by the social war (91-87 BC), neither the people's hate against the Senate, the escape and return of Gaius Marius, the following revenges, killings and violence.

Notes

- The summary of the dialogue in Book II is based on the translation and analysis by May & Wisse 2001

References

- Clark 1911, p. 354 footnote 3.

- De Orat. I,1

- De Orat. I,2

- De Orat. I,3

- De Orat. I,4-6

- De Orat. I,6 (20-21)

- De Orat. I,7

- De Orat. I,8-12

- De Orat. I,13

- De Orat. I,14-15

- De Orat. I,16

- De Orat. I,17-18

- De Orat. I,18 (83-84) - 20

- De Orat. I,21 (94-95)-22 (99-101)

- De Orat. I,22 (102-104)- 23 (105-106)

- De Orat. I,23 (107-109)-28

- De Orat. I,29-30

- De Orat. I,31

- De Orat. I,32

- De Orat. I,33

- De Orat. I,34

- De Orat. I,35

- De Orat.I,35 (161)

- De Orat.I,36

- De Orat.I,37

- De Orat.I,38

- De Orat.I 41

- De Orat.I 42

- De Orat.I 43

- De Orat.I 44

- De Orat.I 45

- De Orat.I 46

- De Orat.I 47

- De Orat.I 48

- De Orat.I 49, 212

- De Orat.I 49, 213-215

- De Orat.I 50

- De Orat.I 51

- De Orat.I 52

- De Orat.I 54

- De Orat.I 55

- De Orat.I 56

- De Orat.I 57

- De Orat.I 58

- De Orat.I 59

- De Orat, I, 60 (254-255)

- De Orat.I 60-61 (259)

- De Orat.I 61 (260)- 62

- .Cicero. in May & Wisse 2001, p. 132

Bibliography

- Clark, Albert Curtis (1911). "Cicero" . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 354.

De Oratore editions

- Critical editions

- M TULLI CICERONIS SCRIPTA QUAE MANSERUNT OMNIA FASC. 3 DE ORATORE edidit KAZIMIERZ F. KUMANIECKI ed. TEUBNER; Stuttgart and Leipzig, anastatic reprint, 1995 ISBN 3-8154-1171-8

- L'Orateur - Du meilleur genre d'orateurs. Collection des universités de France Série latine. Latin text with translation in French.

ISBN 978-2-251-01080-9

Publication Year: June 2008 - M. Tulli Ciceronis De Oratore Libri Tres, with Introduction and Notes by Augustus Samuel Wilkins. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1902. (Reprint: 1961). Available from the Internet Archive here.

- Editions with a commentary

- De oratore libri III / M. Tullius Cicero; Kommentar von Anton D. Leeman, Harm Pinkster. Heidelberg : Winter, 1981-<1996 > Description: v. <1-2, 3 pt.2, 4 >; ISBN 3-533-04082-8 (Bd. 3 : kart.) ISBN 3-533-04083-6 (Bd. 3 : Ln.) ISBN 3-533-03023-7 (Bd. 1) ISBN 3-533-03022-9 (Bd. 1 : Ln.) ISBN 3-8253-0403-5 (Bd. 4) ISBN 3-533-03517-4 (Bd. 2 : kart.) ISBN 3-533-03518-2 (Bd. 2 : Ln.)

- "De Oratore Libri Tres", in M. Tulli Ciceronis Rhetorica (ed. Augustus Samuel Wilkins), Vol. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1892. (Reprint: Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert, 1962). Available from the Internet Archive here.

- Translations

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius (2001). On the Ideal Orator. Translated by May, James M.; Wisse, Jakob. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509197-3.

Further reading

- Elaine Fantham: The Roman World of Cicero's De Oratore, Paperback edition, Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-19-920773-9

External links

- On Oratory and orators (English translation) at the Internet Archive

- Cicero, De Oratore (translated by J.S. Watson) at attalus.org

| Marcus Tullius Cicero | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatises |

|  | ||||

| Orations |

| |||||

| Letters | ||||||

| Related | ||||||