A river delta is a triangular landform created by the deposition of the sediments that are carried by the waters of a river, where the river merges with a body of slow-moving water or with a body of stagnant water. The creation of a river delta occurs at the river mouth, where the river merges into an ocean, a sea, or an estuary, into a lake, a reservoir, or (more rarely) into another river that cannot carry away the sediment supplied by the feeding river. Etymologically, the term river delta derives from the triangular shape (Δ) of the uppercase Greek letter delta. In hydrology, the dimensions of a river delta are determined by the balance between the watershed processes that supply sediment and the watershed processes that redistribute, sequester, and export the supplied sediment into the receiving basin.

River deltas are important in human civilization, as they are major agricultural production centers and population centers. They can provide coastline defence and can impact drinking water supply. They are also ecologically important, with different species' assemblages depending on their landscape position. On geologic timescales, they are also important carbon sinks.

Etymology

A river delta is so named because the shape of the Nile Delta approximates the triangular uppercase Greek letter delta. The triangular shape of the Nile Delta was known to audiences of classical Athenian drama; the tragedy Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus refers to it as the "triangular Nilotic land", though not as a "delta". Herodotus's description of Egypt in his Histories mentions the Delta fourteen times, as "the Delta, as it is called by the Ionians", including describing the outflow of silt into the sea and the convexly curved seaward side of the triangle. Despite making comparisons to other river systems deltas, Herodotus did not describe them as "deltas". The Greek historian Polybius likened the land between the Rhône and Isère rivers to the Nile Delta, referring to both as islands, but did not apply the word delta. According to the Greek geographer Strabo, the Cynic philosopher Onesicritus of Astypalaea, who accompanied Alexander the Great's conquests in India, reported that Patalene (the delta of the Indus River) was "a delta" (Koinē Greek: καλεῖ δὲ τὴν νῆσον δέλτα, romanized: kalei de tēn nēson délta, lit. 'he calls the island a delta'). The Roman author Arrian's Indica states that "the delta of the land of the Indians is made by the Indus river no less than is the case with that of Egypt".

As a generic term for the landform at the mouth of the river, the word delta is first attested in the English-speaking world in the late 18th century, in the work of Edward Gibbon.

Formation

River deltas form when a river carrying sediment reaches a body of water, such as a lake, ocean, or a reservoir. When the flow enters the standing water, it is no longer confined to its channel and expands in width. This flow expansion results in a decrease in the flow velocity, which diminishes the ability of the flow to transport sediment. As a result, sediment drops out of the flow and is deposited as alluvium, which builds up to form the river delta. Over time, this single channel builds a deltaic lobe (such as the bird's-foot of the Mississippi or Ural river deltas), pushing its mouth into the standing water. As the deltaic lobe advances, the gradient of the river channel becomes lower because the river channel is longer but has the same change in elevation (see slope).

As the gradient of the river channel decreases, the amount of shear stress on the bed decreases, which results in the deposition of sediment within the channel and a rise in the channel bed relative to the floodplain. This destabilizes the river channel. If the river breaches its natural levees (such as during a flood), it spills out into a new course with a shorter route to the ocean, thereby obtaining a steeper, more stable gradient. Typically, when the river switches channels in this manner, some of its flow remains in the abandoned channel. Repeated channel-switching events build up a mature delta with a distributary network.

Another way these distributary networks form is from the deposition of mouth bars (mid-channel sand and/or gravel bars at the mouth of a river). When this mid-channel bar is deposited at the mouth of a river, the flow is routed around it. This results in additional deposition on the upstream end of the mouth bar, which splits the river into two distributary channels. A good example of the result of this process is the Wax Lake Delta.

In both of these cases, depositional processes force redistribution of deposition from areas of high deposition to areas of low deposition. This results in the smoothing of the planform (or map-view) shape of the delta as the channels move across its surface and deposit sediment. Because the sediment is laid down in this fashion, the shape of these deltas approximates a fan. The more often the flow changes course, the shape develops closer to an ideal fan because more rapid changes in channel position result in a more uniform deposition of sediment on the delta front. The Mississippi and Ural River deltas, with their bird's feet, are examples of rivers that do not avulse often enough to form a symmetrical fan shape. Alluvial fan deltas, as seen by their name, avulse frequently and more closely approximate an ideal fan shape.

Most large river deltas discharge to intra-cratonic basins on the trailing edges of passive margins due to the majority of large rivers such as the Mississippi, Nile, Amazon, Ganges, Indus, Yangtze, and Yellow River discharging along passive continental margins. This phenomenon is due mainly to three factors: topography, basin area, and basin elevation. Topography along passive margins tend to be more gradual and widespread over a greater area enabling sediment to pile up and accumulate over time to form large river deltas. Topography along active margins tends to be steeper and less widespread, which results in sediments not having the ability to pile up and accumulate due to the sediment traveling into a steep subduction trench rather than a shallow continental shelf.

There are many other lesser factors that could explain why the majority of river deltas form along passive margins rather than active margins. Along active margins, orogenic sequences cause tectonic activity to form over-steepened slopes, brecciated rocks, and volcanic activity resulting in delta formation to exist closer to the sediment source. When sediment does not travel far from the source, sediments that build up are coarser grained and more loosely consolidated, therefore making delta formation more difficult. Tectonic activity on active margins causes the formation of river deltas to form closer to the sediment source which may affect channel avulsion, delta lobe switching, and auto cyclicity. Active margin river deltas tend to be much smaller and less abundant but may transport similar amounts of sediment. However, the sediment is never piled up in thick sequences due to the sediment traveling and depositing in deep subduction trenches.

At the mouth of a river, the change in flow conditions can cause the river to drop any sediment it is carrying. This sediment deposition can generate a variety of landforms, such as deltas, sand bars, spits, and tie channels. Landforms at the river mouth drastically alter the geomorphology and ecosystem.

Types

Deltas are typically classified according to the main control on deposition, which is a combination of river, wave, and tidal processes, depending on the strength of each. The other two factors that play a major role are landscape position and the grain size distribution of the source sediment entering the delta from the river.

Fluvial-dominated deltas

Fluvial-dominated deltas are found in areas of low tidal range and low wave energy. Where the river water is nearly equal in density to the basin water, the delta is characterized by homopycnal flow, in which the river water rapidly mixes with basin water and abruptly dumps most of its sediment load. Where the river water has a higher density than basin water, typically from a heavy load of sediment, the delta is characterized by hyperpycnal flow in which the river water hugs the basin bottom as a density current that deposits its sediments as turbidites. When the river water is less dense than the basin water, as is typical of river deltas on an ocean coastline, the delta is characterized by hypopycnal flow in which the river water is slow to mix with the denser basin water and spreads out as a surface fan. This allows fine sediments to be carried a considerable distance before settling out of suspension. Beds in a hypocynal delta dip at a very shallow angle, around 1 degree.

Fluvial-dominated deltas are further distinguished by the relative importance of the inertia of rapidly flowing water, the importance of turbulent bed friction beyond the river mouth, and buoyancy. Outflow dominated by inertia tends to form Gilbert-type deltas. Outflow dominated by turbulent friction is prone to channel bifurcation, while buoyancy-dominated outflow produces long distributaries with narrow subaqueous natural levees and few channel bifurcations.

The modern Mississippi River delta is a good example of a fluvial-dominated delta whose outflow is buoyancy-dominated. Channel abandonment has been frequent, with seven distinct channels active over the last 5000 years. Other fluvial-dominated deltas include the Mackenzie delta and the Alta delta.

Gilbert deltas

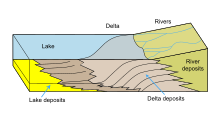

A Gilbert delta (named after Grove Karl Gilbert) is a type of fluvial-dominated delta formed from coarse sediments, as opposed to gently sloping muddy deltas such as that of the Mississippi. For example, a mountain river depositing sediment into a freshwater lake would form this kind of delta. It is commonly a result of homopycnal flow. Such deltas are characterized by a tripartite structure of topset, foreset, and bottomset beds. River water entering the lake rapidly deposits its coarser sediments on the submerged face of the delta, forming steeping dipping foreset beds. The finer sediments are deposited on the lake bottom beyond this steep slope as more gently dipping bottomset beds. Behind the delta front, braided channels deposit the gently dipping beds of the topset on the delta plain.

While some authors describe both lacustrine and marine locations of Gilbert deltas, others note that their formation is more characteristic of the freshwater lakes, where it is easier for the river water to mix with the lakewater faster (as opposed to the case of a river falling into the sea or a salt lake, where less dense fresh water brought by the river stays on top longer). Gilbert himself first described this type of delta on Lake Bonneville in 1885. Elsewhere, similar structures occur, for example, at the mouths of several creeks that flow into Okanagan Lake in British Columbia and form prominent peninsulas at Naramata, Summerland, and Peachland.

Wave-dominated deltas

In wave-dominated deltas, wave-driven sediment transport controls the shape of the delta, and much of the sediment emanating from the river mouth is deflected along the coastline. The relationship between waves and river deltas is quite variable and largely influenced by the deepwater wave regimes of the receiving basin. With a high wave energy near shore and a steeper slope offshore, waves will make river deltas smoother. Waves can also be responsible for carrying sediments away from the river delta, causing the delta to retreat. For deltas that form further upriver in an estuary, there are complex yet quantifiable linkages between winds, tides, river discharge, and delta water levels.

Tide-dominated deltas

Erosion is also an important control in tide-dominated deltas, such as the Ganges Delta, which may be mainly submarine, with prominent sandbars and ridges. This tends to produce a "dendritic" structure. Tidal deltas behave differently from river-dominated and wave-dominated deltas, which tend to have a few main distributaries. Once a wave-dominated or river-dominated distributary silts up, it is abandoned, and a new channel forms elsewhere. In a tidal delta, new distributaries are formed during times when there is a lot of water around – such as floods or storm surges. These distributaries slowly silt up at a more or less constant rate until they fizzle out.

Tidal freshwater deltas

A tidal freshwater delta is a sedimentary deposit formed at the boundary between an upland stream and an estuary, in the region known as the "subestuary". Drowned coastal river valleys that were inundated by rising sea levels during the late Pleistocene and subsequent Holocene tend to have dendritic estuaries with many feeder tributaries. Each tributary mimics this salinity gradient from its brackish junction with the mainstem estuary up to the fresh stream feeding the head of tidal propagation. As a result, the tributaries are considered to be "subestuaries". The origin and evolution of a tidal freshwater delta involves processes that are typical of all deltas as well as processes that are unique to the tidal freshwater setting. The combination of processes that create a tidal freshwater delta result in a distinct morphology and unique environmental characteristics. Many tidal freshwater deltas that exist today are directly caused by the onset of or changes in historical land use, especially deforestation, intensive agriculture, and urbanization. These ideas are well illustrated by the many tidal freshwater deltas prograding into Chesapeake Bay along the east coastline of the United States. Research has demonstrated that the accumulating sediments in this estuary derive from post-European settlement deforestation, agriculture, and urban development.

Estuaries

Other rivers, particularly those on coasts with significant tidal range, do not form a delta but enter into the sea in the form of an estuary. Notable examples include the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the Tagus estuary.

Inland deltas

In rare cases, the river delta is located inside a large valley and is called an inverted river delta. Sometimes a river divides into multiple branches in an inland area, only to rejoin and continue to the sea. Such an area is called an inland delta, and often occurs on former lake beds. The term was first coined by Alexander von Humboldt for the middle reaches of the Orinoco River, which he visited in 1800. Other prominent examples include the Inner Niger Delta, Peace–Athabasca Delta, the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, and the Sistan delta of Iran. The Danube has one in the valley on the Slovak–Hungarian border between Bratislava and Iža.

In some cases, a river flowing into a flat arid area splits into channels that evaporate as it progresses into the desert. The Okavango Delta in Botswana is one example. See endorheic basin.

Mega deltas

The generic term mega delta can be used to describe very large Asian river deltas, such as the Yangtze, Pearl, Red, Mekong, Irrawaddy, Ganges-Brahmaputra, and Indus.

Sedimentary structure

The formation of a delta is complicated, multiple, and cross-cutting over time, but in a simple delta three main types of bedding may be distinguished: the bottomset beds, foreset/frontset beds, and topset beds. This three-part structure may be seen on small scale by crossbedding.

- The bottomset beds are created from the lightest suspended particles that settle farthest away from the active delta front, as the river flow diminishes into the standing body of water and loses energy. This suspended load is deposited by sediment gravity flow, creating a turbidite. These beds are laid down in horizontal layers and consist of the finest grain sizes.

- The foreset beds in turn are deposited in inclined layers over the bottomset beds as the active lobe advances. Foreset beds form the greater part of the bulk of a delta, (and also occur on the lee side of sand dunes). The sediment particles within foreset beds consist of larger and more variable sizes, and constitute the bed load that the river moves downstream by rolling and bouncing along the channel bottom. When the bed load reaches the edge of the delta front, it rolls over the edge, and is deposited in steeply dipping layers over the top of the existing bottomset beds. Underwater, the slope of the outermost edge of the delta is created at the angle of repose of these sediments. As the foresets accumulate and advance, subaqueous landslides occur and readjust overall slope stability. The foreset slope, thus created and maintained, extends the delta lobe outward. In cross section, foresets typically lie in angled, parallel bands, and indicate stages and seasonal variations during the creation of the delta.

- The topset beds of an advancing delta are deposited in turn over the previously laid foresets, truncating or covering them. Topsets are nearly horizontal layers of smaller-sized sediment deposited on the top of the delta and form an extension of the landward alluvial plain. As the river channels meander laterally across the top of the delta, the river is lengthened and its gradient is reduced, causing the suspended load to settle out in nearly horizontal beds over the delta's top. Topset beds are subdivided into two regions: the upper delta plain and the lower delta plain. The upper delta plain is unaffected by the tide, while the boundary with the lower delta plain is defined by the upper limit of tidal influence.

Existential threats to deltas

Human activities in both deltas and the river basins upstream of deltas can radically alter delta environments. Upstream land use change such as anti-erosion agricultural practices and hydrological engineering such as dam construction in the basins feeding deltas have reduced river sediment delivery to many deltas in recent decades. This change means that there is less sediment available to maintain delta landforms, and compensate for erosion and sea level rise, causing some deltas to start losing land. Declines in river sediment delivery are projected to continue in the coming decades.

The extensive anthropogenic activities in deltas also interfere with geomorphological and ecological delta processes. People living on deltas often construct flood defences which prevent sedimentation from floods on deltas, and therefore means that sediment deposition can not compensate for subsidence and erosion. In addition to interference with delta aggradation, pumping of groundwater, oil, and gas, and constructing infrastructure all accelerate subsidence, increasing relative sea level rise. Anthropogenic activities can also destabilise river channels through sand mining, and cause saltwater intrusion. There are small-scale efforts to correct these issues, improve delta environments and increase environmental sustainability through sedimentation enhancing strategies.

While nearly all deltas have been impacted to some degree by humans, the Nile Delta and Colorado River Delta are some of the most extreme examples of the devastation caused to deltas by damming and diversion of water.

Historical data documents show that during the Roman Empire and Little Ice Age (times when there was considerable anthropogenic pressure), there was significant sediment accumulation in deltas. The industrial revolution has only amplified the impact of humans on delta growth and retreat.

Deltas in the economy

Ancient deltas benefit the economy due to their well-sorted sand and gravel. Sand and gravel are often quarried from these old deltas and used in concrete for highways, buildings, sidewalks, and landscaping. More than 1 billion tons of sand and gravel are produced in the United States alone. Not all sand and gravel quarries are former deltas, but for ones that are, much of the sorting is already done by the power of water.

Urban areas and human habitation tend to be located in lowlands near water access for transportation and sanitation. This makes deltas a common location for civilizations to flourish due to access to flat land for farming, freshwater for sanitation and irrigation, and sea access for trade. Deltas often host extensive industrial and commercial activities, and agricultural land is frequently in conflict. Some of the world's largest regional economies are located on deltas such as the Pearl River Delta, Yangtze River Delta, European Low Countries and the Greater Tokyo Area.

Examples

See also: Category:River deltasThe Ganges–Brahmaputra Delta, which spans most of Bangladesh and West Bengal and empties into the Bay of Bengal, is the world's largest delta.

The Selenga River delta in the Russian republic of Buryatia is the largest delta emptying into a body of fresh water, in its case Lake Baikal.

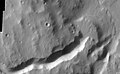

Deltas on Mars

Researchers have found a number of examples of deltas that formed in Martian lakes. Finding deltas is a major sign that Mars once had large amounts of water. Deltas have been found over a wide geographical range. Below are pictures of a few.

-

Delta in Ismenius Lacus quadrangle, as seen by THEMIS

Delta in Ismenius Lacus quadrangle, as seen by THEMIS

-

Delta in Lunae Palus quadrangle, as seen by THEMIS

Delta in Lunae Palus quadrangle, as seen by THEMIS

-

Delta in Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle as seen by THEMIS

Delta in Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle as seen by THEMIS

-

Probable delta in Eberswalde crater, as seen by Mars Global Surveyor. Image in Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle.

Probable delta in Eberswalde crater, as seen by Mars Global Surveyor. Image in Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle.

See also

- Alluvial fan – Fan-shaped deposit of sediment

- Avulsion (river) – Rapid abandonment of a river channel and formation of a new channel

- Estuary – Partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water

- Levee – Ridge or wall to hold back water

- Nile Delta – Delta produced by the Nile River at its mouth in the Mediterranean Sea

- Regressive delta

- Pearl River Delta – Complex delta in south-east China

References

- Miall, A. D. 1979. Deltas. in R. G. Walker (ed) Facies Models. Geological Association of Canada, Hamilton, Ontario.

- Elliot, T. 1986. Deltas. in H. G. Reading (ed.). Sedimentary Environments and Facies. Backwell Scientific Publications, Oxford.

- Blum, M.D.; Törnqvist, T.E. (2000). "Fluvial Responses to Climate and Sea-level Change: A Review and Look Forward". Sedimentology. 47: 2–48. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3091.2000.00008.x. S2CID 140714394.

- ^ Pasternack, Gregory B.; Brush, Grace S.; Hilgartner, William B. (2001-04-01). "Impact of historic land-use change on sediment delivery to a Chesapeake Bay subestuarine delta". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 26 (4): 409–427. Bibcode:2001ESPL...26..409P. doi:10.1002/esp.189. ISSN 1096-9837. S2CID 129080402.

- Schneider, Pia; Asch, Folkard (2020). "Rice production and food security in Asian Mega deltas—A review on characteristics, vulnerabilities and agricultural adaptation options to cope with climate change". Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science. 206 (4): 491–503. doi:10.1111/jac.12415. ISSN 1439-037X.

- ^ Anthony, Edward J. (2015-03-01). "Wave influence in the construction, shaping and destruction of river deltas: A review". Marine Geology. 361: 53–78. Bibcode:2015MGeol.361...53A. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2014.12.004.

- Hage, Sophie; Romans, Brian W.; Peploe, Thomas G. E.; Poyatos-Moré, Miquel; Haeri Ardakani, Omid; Bell, Daniel; Englert, Rebecca G.; Kaempfe-Droguett, Sebastian A.; Nesbit, Paul R.; Sherstan, Georgia; Synnott, Dane P.; Hubbard, Stephen M. (24 October 2022). "High rates of organic carbon burial in submarine deltas maintained on geological timescales". Nature Geoscience. 15 (1): 919–924. Bibcode:2022NatGe..15..919H. doi:10.1038/s41561-022-01048-4. S2CID 253145418. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ Celoria, Francis (1966). "Delta as a geographical concept in Greek literature". Isis. 57 (3): 385–388. doi:10.1086/350146. JSTOR 228368. S2CID 143811840.

- "Word Stories: Unexpected Relatives for Xmas". Druide. January 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-10-22. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- "How a Delta Forms Where River Meets Lake". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2014-08-12. Archived from the original on 2017-12-12. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- "Dr. Gregory B. Pasternack – Watershed Hydrology, Geomorphology, and Ecohydraulics :: TFD Modeling". pasternack.ucdavis.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- Boggs, Sam (2006). Principles of sedimentology and stratigraphy (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 289–306. ISBN 0131547283.

- Slingerland, R. and N. D. Smith (1998), "Necessary conditions for a meandering-river avulsion", Geology (Boulder), 26, 435–438.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. 295.

- Leeder, M. R. (2011). Sedimentology and sedimentary basins: from turbulence to tectonics (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 388. ISBN 9781405177832.

- ^ Milliman, J. D.; Syvitski, J. P. M. (1992). "Geomorphic/Tectonic Control of Sediment Discharge to the Ocean: The Importance of Small Mountainous Rivers". The Journal of Geology. 100 (5): 525–544. Bibcode:1992JG....100..525M. doi:10.1086/629606. JSTOR 30068527. S2CID 22727856.

- ^ Goodbred, S. L.; Kuehl, S. A. (2000). "The significance of large sediment supply, active tectonism, and eustasy on margin sequence development: Late Quaternary stratigraphy and evolution of the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta". Sedimentary Geology. 133 (3–4): 227–248. Bibcode:2000SedG..133..227G. doi:10.1016/S0037-0738(00)00041-5.

- ^ Galloway, W.E., 1975, Process framework for describing the morphologic and stratigraphic evolution of deltaic depositional systems, in Brousard, M.L., ed., Deltas, Models for Exploration: Houston Geological Society, Houston, Texas, pp. 87–98.

- Nienhuis, J.H., Ashton, A.D., Edmonds, D.A., Hoitink, A.J.F., Kettner, A.J., Rowland, J.C. and Törnqvist, T.E., 2020. Global-scale human impact on delta morphology has led to net land area gain. Nature, 577(7791), pp.514-518.

- Perillo, G. M. E. 1995. Geomorphology and Sedimentology of Estuaries. Elsevier Science B.V., New York.

- Orton, G.J.; Reading, H.G. (1993). "Variability of deltaic processes in terms of sediment supply, with particular emphasis on grain size". Sedimentology. 40 (3): 475–512. Bibcode:1993Sedim..40..475O. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3091.1993.tb01347.x.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. 293.

- Boggs 2006, p. 294.

- Boggs 2006, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Characteristics of deltas. (Available archived at – checked Dec 2008.)

- Bernard Biju-Duval, J. Edwin Swezey. "Sedimentary Geology". Page 183. ISBN 2-7108-0802-1. Editions TECHNIP, 2002. Partial text on Google Books.

- Gilbert, G.K. (1885). The topographic features of lake shores. US Government Printing Office. pp. 104–107. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- Backert, Nicolas; Ford, Mary; Malartre, Fabrice (February 2010). "Architecture and sedimentology of the Kerinitis Gilbert-type fan delta, Corinth Rift, Greece". Sedimentology. 57 (2): 543–586. Bibcode:2010Sedim..57..543B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3091.2009.01105.x. S2CID 129299341.

- ^ "Geological and Petrophysical Characterization of the Ferron Sandstone for 3-D Simulation of a Fluvial-deltaic Reservoir". By Thomas C. Chidsey, Thomas C. Chidsey Jr (ed), Utah Geological Survey, 2002. ISBN 1-55791-668-3. Pages 2–17. Partial text on Google Books.

- "Dr. Gregory B. Pasternack – Watershed Hydrology, Geomorphology, and Ecohydraulics :: TFD Hydrometeorology". pasternack.ucdavis.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- Pasternack, Gregory B.; Hinnov, Linda A. (October 2003). "Hydrometeorological controls on water level in a vegetated Chesapeake Bay tidal freshwater delta" (PDF). Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 58 (2): 367–387. Bibcode:2003ECSS...58..367P. doi:10.1016/s0272-7714(03)00106-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-24. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- ^ Fagherazzi S., 2008, Self-organization of tidal deltas, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 105 (48): 18692–18695,

- "Gregory B. Pasternack – Watershed Hydrology, Geomorphology, and Ecohydraulics :: Tidal Freshwater Deltas". pasternack.ucdavis.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- Pasternack, G. B. (1998). Physical dynamics of tidal freshwater delta evolution (PhD dissertation). The Johns Hopkins University. OCLC 49850378.

- Pasternack, Gregory B.; Hilgartner, William B.; Brush, Grace S. (2000-09-01). "Biogeomorphology of an upper Chesapeake Bay river-mouth tidal freshwater marsh". Wetlands. 20 (3): 520–537. doi:10.1672/0277-5212(2000)020<0520:boaucb>2.0.co;2. ISSN 0277-5212. S2CID 25962433.

- Pasternack, Gregory B; Brush, Grace S (2002-03-01). "Biogeomorphic controls on sedimentation and substrate on a vegetated tidal freshwater delta in upper Chesapeake Bay". Geomorphology. 43 (3–4): 293–311. Bibcode:2002Geomo..43..293P. doi:10.1016/s0169-555x(01)00139-8.

- Pasternack, Gregory B.; Brush, Grace S. (1998-09-01). "Sedimentation cycles in a river-mouth tidal freshwater marsh". Estuaries and Coasts. 21 (3): 407–415. doi:10.2307/1352839. ISSN 0160-8347. JSTOR 1352839. S2CID 85961542. Archived from the original on 2019-02-07. Retrieved 2018-09-08.

- Gottschalk, L. C. (1945). "Effects of soil erosion on navigation in upper Chesapeake Bay". Geographical Review. 35 (2): 219–238. doi:10.2307/211476. JSTOR 211476.

- Brush, G. S. (1984). "Patterns of recent sediment accumulation in Chesapeake Bay (Virginia-Maryland, U.S.A.) tributaries". Chemical Geology. 44 (1–3): 227–242. Bibcode:1984ChGeo..44..227B. doi:10.1016/0009-2541(84)90074-3.

- Orson, R. A.; Simpson, R. L.; Good, R. E. (1992). "The paleoecological development of a late Holocene, tidal freshwater marsh of the upper Delaware River estuary". Estuaries and Coasts. 15 (2): 130–146. doi:10.2307/1352687. JSTOR 1352687. S2CID 85128464.

- Lucie, Toussaint; Philippe, Archambault; Laura, Del Franco; Arnaud, Huvet; Matthieu, Waeles; Julien, Gigault; Ika, Paul-Pont (September 2024). "The largest estuary on the planet is not spared from plastic pollution: Case of the St. Lawrence River Estuary". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 206: 116780. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.116780.

- Rodrigues, Marta; Cravo, Alexandra; Freire, Paula; Rosa, Alexandra; Santos, Daniela (2020-06-20). "Temporal assessment of the water quality along an urban estuary (Tagus estuary, Portugal)". Marine Chemistry. 223: 103824. doi:10.1016/j.marchem.2020.103824. ISSN 0304-4203.

- Meade, Robert H. (January 1994). "Suspended sediments of the modern Amazon and Orinoco rivers". Quaternary International. 21: 29–39. Bibcode:1994QuInt..21...29M. doi:10.1016/1040-6182(94)90019-1.

- Dadson, Simon J.; Ashpole, Ian; Harris, Phil; Davies, Helen N.; Clark, Douglas B.; Blyth, Eleanor; Taylor, Christopher M. (4 December 2010). "Wetland inundation dynamics in a model of land surface climate: Evaluation in the Niger inland delta region". Journal of Geophysical Research. 115 (D23): D23114. Bibcode:2010JGRD..11523114D. doi:10.1029/2010JD014474.

- Leconte, Robert; Pietroniro, Alain; Peters, Daniel L.; Prowse, Terry D. (2001). "Effects of flow regulation on hydrologic patterns of a large, inland delta". Regulated Rivers: Research & Management. 17 (1): 51–65. doi:10.1002/1099-1646(200101/02)17:1<51::AID-RRR588>3.0.CO;2-V.

- Hart, Jeff; Hunter, John (2004). "Restoring Slough and River Banks with Biotechnical Methods in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta". Ecological Restoration. 22 (4): 262–68. doi:10.3368/er.22.4.262. JSTOR 43442774.. S2CID 84968414.

- van Beek, Eelco; Bozorgy, Babak; Vekerdy, Zoltán; Meijer, Karen (June 2008). "Limits to agricultural growth in the Sistan Closed Inland Delta, Iran". Irrigation and Drainage Systems. 22 (2): 131–143. doi:10.1007/s10795-008-9045-7. S2CID 111027461.

- Petráš, Rudolf; Mecko, Julian; Oszlányi, Július; Petrášová, Viera; Jamnická, Gabriela (August 2013). "Landscape of Danube inland-delta and its potential of poplar bioenergy production". Biomass and Bioenergy. 55: 68–72. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.05.022.

- Neuenschwander, A.L.; Crawford, M.M.; Ringrose, S. (2002). "Monitoring of seasonal flooding in the Okavango Delta using EO-1 data". IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. Vol. 6. pp. 3124–3126. doi:10.1109/IGARSS.2002.1027105. ISBN 0-7803-7536-X. S2CID 33284178.

- Seto, Karen C. (December 2011). "Exploring the dynamics of migration to mega-delta cities in Asia and Africa: Contemporary drivers and future scenarios". Global Environmental Change. 21: S94 – S107. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.08.005.

- Darby, Stephen E.; Hackney, Christopher R.; Leyland, Julian; Kummu, Matti; Lauri, Hannu; Parsons, Daniel R.; Best, James L.; Nicholas, Andrew P.; Aalto, Rolf (November 2016). "Fluvial sediment supply to a mega-delta reduced by shifting tropical-cyclone activity" (PDF). Nature. 539 (7628): 276–279. Bibcode:2016Natur.539..276D. doi:10.1038/nature19809. PMID 27760114. S2CID 205251150. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2020-12-22.

- D.G.A Whitten, The Penguin Dictionary of Geology (1972)

- ^ Robert L. Bates, Julia A. Jackson, Dictionary of Geological Terms AGI (1984)

- Hori, K. and Saito, Y. Morphology and Sediments of Large River Deltas. Tokyo, Japan: Tokyo Geographical Society, 2003

- Day, John W.; Agboola, Julius; Chen, Zhongyuan; D’Elia, Christopher; Forbes, Donald L.; Giosan, Liviu; Kemp, Paul; Kuenzer, Claudia; Lane, Robert R.; Ramachandran, Ramesh; Syvitski, James (2016-12-20). "Approaches to defining deltaic sustainability in the 21st century". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. Sustainability of Future Coasts and Estuaries. 183: 275–291. Bibcode:2016ECSS..183..275D. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2016.06.018. ISSN 0272-7714. Archived from the original on 2024-05-25. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- ^ Syvitski, James P. M.; Kettner, Albert J.; Overeem, Irina; Hutton, Eric W. H.; Hannon, Mark T.; Brakenridge, G. Robert; Day, John; Vörösmarty, Charles; Saito, Yoshiki; Giosan, Liviu; Nicholls, Robert J. (2009-10-01). "Sinking deltas due to human activities". Nature Geoscience. 2 (10): 681–686. Bibcode:2009NatGe...2..681S. doi:10.1038/ngeo629. hdl:1912/3207. ISSN 1752-0908. Archived from the original on 2021-05-05. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- Dunn, Frances E; Darby, Stephen E; Nicholls, Robert J; Cohen, Sagy; Zarfl, Christiane; Fekete, Balázs M (2019-08-06). "Projections of declining fluvial sediment delivery to major deltas worldwide in response to climate change and anthropogenic stress". Environmental Research Letters. 14 (8): 084034. Bibcode:2019ERL....14h4034D. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab304e. ISSN 1748-9326.

- Syvitski, James P. M. (2008-04-01). "Deltas at risk". Sustainability Science. 3 (1): 23–32. doi:10.1007/s11625-008-0043-3. ISSN 1862-4057. S2CID 128976925. Archived from the original on 2024-05-25. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- Minderhoud, P S J; Erkens, G; Pham, V H; Bui, V T; Erban, L; Kooi, H; Stouthamer, E (2017-06-01). "Impacts of 25 years of groundwater extraction on subsidence in the Mekong delta, Vietnam". Environmental Research Letters. 12 (6): 064006. Bibcode:2017ERL....12f4006M. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aa7146. ISSN 1748-9326. PMC 6192430. PMID 30344619.

- ABAM, T. K. S. (2001-02-01). "Regional hydrological research perspectives in the Niger Delta". Hydrological Sciences Journal. 46 (1): 13–25. Bibcode:2001HydSJ..46...13A. doi:10.1080/02626660109492797. ISSN 0262-6667. S2CID 129784677.

- Hackney, Christopher R.; Darby, Stephen E.; Parsons, Daniel R.; Leyland, Julian; Best, James L.; Aalto, Rolf; Nicholas, Andrew P.; Houseago, Robert C. (2020-03-01). "River bank instability from unsustainable sand mining in the lower Mekong River". Nature Sustainability. 3 (3): 217–225. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0455-3. hdl:10871/40127. ISSN 2398-9629. S2CID 210166330. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- Eslami, Sepehr; Hoekstra, Piet; Nguyen Trung, Nam; Ahmed Kantoush, Sameh; Van Binh, Doan; Duc Dung, Do; Tran Quang, Tho; van der Vegt, Maarten (2019-12-10). "Tidal amplification and salt intrusion in the Mekong Delta driven by anthropogenic sediment starvation". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 18746. Bibcode:2019NatSR...918746E. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-55018-9. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6904557. PMID 31822705.

- Ali, Elham M.; El-Magd, Islam A. (2016-03-01). "Impact of human interventions and coastal processes along the Nile Delta coast, Egypt during the past twenty-five years". The Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Research. 42 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ejar.2016.01.002. ISSN 1687-4285.

- Witze, Alexandra (2014-03-20). "Water returns to arid Colorado River delta". Nature News. 507 (7492): 286–287. Bibcode:2014Natur.507..286W. doi:10.1038/507286a. PMID 24646976.

- Maselli, Vittorio; Trincardi, Fabio (2013-05-31). "Man made deltas". Scientific Reports. 3: 1926. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E1926M. doi:10.1038/srep01926. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 3668317. PMID 23722597.

- "Mineral Photos – Sand and Gravel". Mineral Information Institute. 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-10-06. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- A., Stefan (2017-05-22). "Why are cities located where they are?". This City Knows. Archived from the original on 2019-06-06. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- "Appendix A: The Major River Deltas Of The World" (PDF). Louisiana State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-02-22. Retrieved 2022-02-22.

- Irwin III, R. et al. 2005. An intense terminal epoch of widespread fluvial activity on early Mars: 2. Increased runoff and paleolake development. Journal of Geophysical Research: 10. E12S15

Bibliography

- Renaud, F. and C. Kuenzer 2012: The Mekong Delta System – Interdisciplinary Analyses of a River Delta, Springer, ISBN 978-94-007-3961-1, doi:10.1007/978-94-007-3962-8, pp. 7–48

- KUENZER C. and RENAUD, F. 2012: Climate Change and Environmental Change in River Deltas Globally. In (eds.): Renaud, F. and C. Kuenzer 2012: The Mekong Delta System – Interdisciplinary Analyses of a River Delta, Springer, ISBN 978-94-007-3961-1, doi:10.1007/978-94-007-3962-8, pp. 7–48

- Ottinger, M.; Kuenzer, C.; LIU; Wang, S.; Dech, S. (2013). "Monitoring Land Cover Dynamics in the Yellow River Delta from 1995 to 2010 based on Landsat 5 TM". Applied Geography. 44: 53–68. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2013.07.003.

- Claudia Kuenzer, Valentin Heimhuber, Juliane Huth, Stefan Dech: Remote Sensing for the Quantification of Land Surface Dynamics in Large River Delta Regions - A Review. Remote Sensing, 11(17), 2019, S. 1-42. doi: 10.3390/rs11171985. ISSN 2072-4292.

- Michel Leonard Wolters, Claudia Kuenzer: Vulnerability assessments of coastal river deltas - categorization and review. Journal of Coastal Conservation, 3/2015 (3/2015), 2015, S. 1-24, doi: 10.1007/s11852-015-0396-6. ISSN 1400-0350.

External links

- Louisiana State University Geology – World Deltas

- http://www.wisdom.eoc.dlr.de WISDOM Water-related Information System for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong Delta

- Wave-dominated river deltas on coastalwiki.org – A coastalwiki.org page on wave-dominated river deltas

| River morphology | |

|---|---|

| Large-scale features | |

| Alluvial rivers | |

| Bedrock river | |

| Bedforms | |

| Regional processes | |

| Mechanics | |

| Wetlands | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types and landforms |

| ||||

| Life | |||||

| Soil mechanics | |||||

| Processes | |||||

| Classifications | |||||

| Conservation |

| ||||

| Related articles | |||||