| This article was nominated for deletion. The discussion was closed on 11 June 2024 with a consensus to merge the content into the article Australian cricket team in England in 1948. If you find that such action has not been taken promptly, please consider assisting in the merger instead of re-nominating the article for deletion. To discuss the merger, please use the destination article's talk page. (June 2024) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Sir Donald George Bradman | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | (1908-08-27)27 August 1908 Cootamundra, New South Wales, Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 25 February 2001(2001-02-25) (aged 92) Kensington Park, Adelaide, Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | The Don, The Boy from Bowral, Braddles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.70 m (5 ft 7 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right-arm leg break | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Batsman | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut | 10 June 1948 v England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 14 August 1948 v England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Test and First-class statistics from ESPNCricinfo, 12 December 2007 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Don Bradman toured England in 1948 with an Australian cricket team that went undefeated in their 34 tour matches, including the five Ashes Tests. Bradman was the captain, one of three selectors, and overall a dominant figure of what was regarded as one of the finest teams of all time, earning the sobriquet The Invincibles.

Generally regarded as the greatest batsman in the history of cricket, the right-handed Bradman played in all five Tests as captain at No. 3. Bradman was more influential than other Australian captains because he was also one of the three selectors who had a hand in choosing the squad. He was also a member of the Australian Board of Control while still playing, a privilege that no other person has held. At the age of 40, Bradman was by far the oldest player on the team; three-quarters of his team were at least eight years younger, and some viewed him as a father figure. Coupled with his status as a national hero, cricketing ability and influence as an administrator, this associated the team more closely to him than other teams to their respective captains. Bradman's iconic stature as a cricketer also led to record-breaking public interest and attendances at the matches on tour.

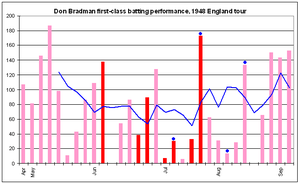

Bradman ended the first-class matches atop the batting aggregates and averages, with 2428 runs at 89.92, and eleven centuries, the most by any player. Despite his success, his troubles against Alec Bedser's leg trap—he fell three consecutive times in the Tests and twice in other matches to bowlers using this ploy—were the subject of much discussion.

Bradman scored 138 in the first innings of the First Test at Trent Bridge, laying the foundation for Australia's 509, which set up a lead of 344 and eventual victory. In the Fourth Test at Headingley, he scored an unbeaten 173 on a deteriorating pitch on the final day, combining in a triple-century partnership with Arthur Morris as Australia scored 3/404 in the second innings to win by seven wickets. This set a world record for the highest ever successful run-chase in Test history. The tour was Bradman's international farewell, and when needing only four runs for a Test career average of exactly 100, he bowed out with a second ball duck in the Fifth Test at The Oval, bowled by an Eric Hollies googly. Australia nevertheless won the Test to complete a 4–0 series win, and Bradman ended the series with 508 runs at 72.57, with two centuries. Only Morris—with three centuries—scored more runs in the five Tests. Bradman's Test average for the series was the third-highest among the Australians, behind that of Sid Barnes and Morris.

Background

Bradman had almost opted out of the tour, citing business commitments in Australia; at the time, it was not possible to make a living from cricket. Prior to the campaign in England, Australia hosted India for a five-Test series during the southern hemisphere summer of 1947–48. Australia easily defeated the tourists 4–0, and Bradman and his fellow selectors Chappie Dwyer and Jack Ryder thus began planning for the tour of England. Bradman made it publicly known that he wanted his team to become the first to play an English summer without defeat. England had agreed to make a new ball available every 55 overs, instead of the previous rule of after 200 runs had been scored. As the run rate was generally much slower than 3.64, 55 overs would usually elapse long before 200 runs were scored. This meant that the ball was in a shiny state more often, and thereby more conducive to fast and swing bowling. Bradman and his colleagues thus chose the team with an emphasis on strong batting and fast bowling, basing his strategy on an intense speed attack against England's batsmen. His 17-man squad sailed for England and arrived in mid-April.

Early tour

Australia traditionally fielded its first-choice team in the tour opener, which was customarily against Worcestershire at the end of April. Bradman thus captained against Worcestershire with Australia bowling first and dismissing the hosts for 233. After Sid Barnes and Arthur Morris put on a partnership of 79 runs in 99 minutes, Bradman came in at No. 3 and put on a stand of 186 in 152 minutes with Morris, before falling for 107, having hit 15 fours. Morris narrowly beat Bradman to score Australia's first century on tour, reaching triple figures while Bradman's score was on 99. Bradman declared Australia's innings at 7/462 and the hosts fell for 212 to complete an Australian victory by an innings and 17 runs.

In the next match, against Leicestershire, Bradman won the toss and elected to bat, promoting Keith Miller ahead of himself to No. 3. As Miller came out to bat, the large crowd mobbed the players' entrance only to see that Bradman was not batting in his customary position. Bradman came to the crease at 2/157, and after initially being troubled by the left-arm unorthodox spin of Australian expatriate Jack Walsh, added 159 with Miller before falling for 81. Australia compiled 448 and bowled out the home side for 130 and 147 to win by an innings, with Bradman taking one catch.

The Australians then proceeded to play Yorkshire, on a damp pitch that suited slower bowling. Bradman rested himself and returned to London, so his deputy Lindsay Hassett led the team. Yorkshire were bowled out in difficult batting conditions for 71, before Australia replied with 101. The hosts were then bowled out for 89. Chasing 60 for victory, the Australian top order collapsed to 6/31. Neil Harvey and Don Tallon survived a dropped catch and a stumping opportunity, before seeing Australia home by four wickets. It was the closest Australia came to defeat for the whole tour.

Bradman then returned in the next match against Surrey at The Oval in London, winning the toss and electing to bat. The last time Australia had played at the ground was the Fifth Test in 1938, when England declared at a world record score of 7/903; Bradman had hurt his ankle, and was unable to bat as Australia fell to the largest defeat in Test history. This match was a far different experience for the Australians. Barnes and Morris put on 136 before Bradman came in to join Barnes; together they added another 207 before Barnes fell for 176. Bradman started slowly and was heckled by the crowd for taking 80 minutes to reach 50, but accelerated and went on to score 146 before being dismissed at 3/403, with Australia proceeding to be all out for 632. He had attacked the medium pacers with his pull shot, but had some difficulties reading the left arm wrist spin of Australian expatriate John McMahon, nearly being caught behind the wicket on multiple occasions. Australia then bowled Surrey out for 141 and 195 to win by an innings.

Bradman rested himself for the next match against Cambridge University, leaving Hassett to orchestrate another innings victory. Bradman returned for the following match against Essex, and batted first after winnings the toss. Bill Brown opened with Barnes and they put on 145 in 97 minutes before Barnes hit his own wicket and was out. Bradman came in and seized the initiative, reaching 42 in the 20 minutes before lunch, including five fours from one over by Frank Vigar which subsequently entered Essex club folklore, as Australia passed 200. Bradman and Brown put on a second-wicket partnership of 219 in 90 minutes before Brown was out for 153 from three hours of batting, with the score at 2/364. After Miller fell without scoring on the next ball, Ron Hamence joined Bradman and they put on another 88 before the Australian skipper was out for 187 at 4/452. Bradman had added his last 87 runs in 48 minutes, hitting a total of 32 fours. Australia was out for 721 at stumps, setting a world record for the most runs in a single day's play in first-class cricket; the record still stands. The tourists completed victory by an innings and 451 runs, their biggest winning margin for the tour. Bradman rested himself for the next match against Oxford University, which resulted in another innings victory.

The next match was against the Marylebone Cricket Club at Lord's in late-May. The MCC fielded seven players who would represent England in the Tests, and were basically a full strength Test team, as were Australia, who fielded their first-choice team. Bradman captained the team and batted at No. 3. Barring one change in the bowling department, the same team would line up for Australia in the First Test, with the top six batsmen playing in the same positions. It was a chance for both teams to gain a psychological advantage. Australia won the toss and batted but stumbled early. Morris was out for five and Bradman came in to join Barnes at 1/11. The pair added 160 before Barnes fell and Hassett came in to join his captain. They took the score to 200 before the Bradman fell for 98, leaving Australia at 3/200. It was Bradman's highest score under 100 in first-class cricket and in his disappointment, he was slow to leave the ground after his dismissal. Bradman's men went on to amass 552 and bowled out the hosts for 189 and 205 to win by an innings, with Bradman catching his opposite number Norman Yardley in the second innings. Up to this point, Bradman had played in five of the first eight matches, all of which were won, seven by an innings. He had scored 107, 81, 146, 187 and 98, yielding a total of 619 runs at an average of 123.80.

The MCC match was followed by Australia's first non-victory of the tour, against Lancashire. Australia were sent in to bat and dismissed for 204, with Bradman bowled by an arm ball from Malcolm Hilton for 11, his first score on the tour below 80. The hosts replied with 182 and in the second innings, Bradman was again dismissed by Hilton, this time for 43 as the tourists reached 4/259 at the end of play. When Hilton came on, Bradman attempted to seize the initiative and hit him out of the attack, but missed his first two balls. On the third ball, he charged out of his crease and swung across the line, missed, fell over and was stumped. Hilton's achievement garnered widespread press attention, particularly in Lancashire.

In the following match against Nottinghamshire, the hosts batted first and made 179. Bradman joined Brown at 1/32 and they took the score to 197 when Bradman fell for 86. The tourists reached 400 and the hosts ended at 8/299 in the second innings to hang on for a draw. Bradman rested himself for the next fixture against Hampshire, and Australia were dismissed for 117 on a drying pitch in reply to the home side's 195, the first time they had conceded a first innings lead in the tour. Australia would have been in deeper trouble but for a flurry of sixes by Miller. Hampshire were then bowled out for 103 to leave Australia a target of 182, and this time the tourists batted with much more authority to seal an eight-wicket win. The tourists had survived another tight battle under the leadership of Hassett. The final match before the First Test was against Sussex. Australia skittled the hosts for 86 before Morris and Brown put on an opening stand of 153. Bradman then joined Morris, and gave two early chances. He was dropped on two and escaped a stumping on 25. He and Morris put on 189 before the latter fell for 184. Bradman then ended his Test preparation by reaching 109, in 124 minutes with 12 fours, and declaring at 5/549, before completing another innings victory.

First Test

Main article: First Test, 1948 Ashes seriesAustralia headed into the First Test at Trent Bridge starting on 10 June with ten wins and two draws from twelve tour matches, with eight innings victories. It was thought that Bradman would play a specialist leg spinner, but he changed his mind on the first morning when rain was forecast. Bill Johnston, a left-arm paceman and orthodox spinner, was played in the hope of exploiting a wet wicket. This was the only change from the teams that Australia had fielded in the matches against Worcestershire and the MCC. Yardley won the toss and elected to bat. Pundits predicted that the pitch would be ideal for batting apart from some assistance to fast bowlers in the first hour, as the surface of the pitch had become moist following overnight rain, assisting seam bowling. Australia's selection policy meant that their reserve opener Brown would bat out of position in the middle order while Barnes and Morris opened, while Neil Harvey was dropped despite making a century in Australia's most recent Test against India.

Despite an injury to pace spearhead Ray Lindwall, Bradman's fast bowlers reduced England in their first innings to 8/74 before finishing them off for 165. Bradman dropped two catches in this innings. English gloveman Godfrey Evans came to the crease with the score at 6/60, and hit Johnston hard to cover, where the ball went through Bradman for a boundary. The second chance went through Bradman's hand and struck him in the abdomen. However, these missed catches did not cost Australia much, as Evans was soon caught at short leg by Morris close in, leaving England at 7/74. England managed to recover somewhat after Laker and Bedser added 89 runs in only 73 minutes for the ninth wicket. At first, Bradman did not appear concerned by the partnership, and it was surmised that he may have been happy for England to continue batting so that his top order would not have to bat in fading light towards the end of the afternoon, but he became anxious as the total continued to mount and both Bedser and Laker appeared comfortable.

On the second day, Morris fell at 1/73 and Bradman came in to join Barnes. Yardley set a defensive field, employing leg theory to slow the scoring. He packed the leg side with fielders and ordered Alec Bedser to bowl at leg stump. Bradman almost edged the second ball onto his stumps, before defending uneasily for a period. While Jim Laker stopped the scoring at the other end, Bradman managed only four runs in his first 20 minutes. The Australian captain regarded Bedser as the finest seam bowler he faced in his career, and he batted in a circumspect manner as he sought to establish himself. At the other end, Bradman misjudged a ball from Laker and an incorrectly executed cut shot narrowly went wide of the slip fielder. Now aged 40, Bradman's reflexes had slowed and he no longer started his innings as confidently as he had done in the past.

The score progressed to 121 when Barnes fell to Laker. Miller came in and was dismissed for a duck without further addition to Australia's total. The hard-hitting Miller had come in at No. 4, a position usually occupied by the more sedate Hassett, indicating that Bradman may have been looking to attack, but the change in batting order failed. All the while, Australia had been scoring slowly, as they would throughout the day. Brown came in, but he looked unaccustomed to batting in the middle order. The Australian captain decided to hasten the new ball by using his feet to get to the pitch of the ball to attack the spinners, hitting them through the off side. Yardley took the second new ball, but this move backfired as Bradman struck his first boundary in over 80 minutes, and in the first 40 minutes after lunch, 43 runs were added. Yardley then took the second new ball. Bradman struck his first boundary in more than 80 minutes but the run rate remained low. Australia passed England's total before Yardley brought himself on to bowl and removed Brown. This ended a 64-run stand with Bradman in 58 minutes, and Hassett came in at 4/185. Following the departure of Brown, the Australian scoring slowed as Bradman changed the team strategy to one of attempting to bat only once.

Yardley continued to employ a leg side field, as he and Barnett bowled outside leg stump. During one over, Bradman did not attempt a single shot and then put his hands on his hips. During the 15 minutes before the tea break, Bradman did not add a single run and was heckled by the crowd for his lack of scoring. The Australian captain reached the tea break on 78; 55 minutes after the resumption of play he played a cover drive against Bedser to reach his century in 218 minutes. It was his 28th Test century, and his 18th in Ashes Tests; the last 29 runs took 70 minutes. It was one of his slower innings as Yardley focused on stopping runs rather than taking wickets. Nevertheless, Bradman had appeared comfortable after the early stages of his innings, and patiently scored most of his runs between mid-off and mid-on, often from the back foot. After the Australian captain had reached his milestone, many of the spectators began to leave the ground, content with what they had seen. Bradman added a further 30 in the last hour to end with 130. Australia batted to stumps on the second day without further loss, ending at 4/293, a lead of 128.

After the day's play, former Australian Test leg spinner Bill O'Reilly and former teammate of Bradman, then a journalist, consulted Bedser on his use of leg theory. O'Reilly had much experience in attacking leg stump in his career and helped Bedser refine his leg trap plan to ensnare Bradman.

On the third morning, amid sunshine, Bradman resumed on 130, before progressing to 132 and becoming the first player to pass 1,000 runs for the English season. The Australian captain was not aware of the reason for the spontaneous crowd applause until notified by wicket-keeper Evans. Bedser was bowling and soon implemented O'Reilly's variation of the leg trap. Hutton was moved from leg-slip to a squarer position at short fine leg, around 11 metres from the bat. Two short legs and a mid on were put in place. Bradman drove Bedser through cover for a boundary, but on the next ball, his innings was terminated at 138 when he glanced an inswinger from Bedser to Hutton at short fine leg, where he caught the ball without having to move. Bradman had batted for 290 minutes and faced 321 balls and Johnson replaced him with Australia at 5/305. Bedser waved to O'Reilly in the press box. When former Australian Test cricketer and journalist Jack Fingleton reported what his friend and former team-mate O'Reilly had done, there was some debate in the media as to whether O'Reilly's actions in advising Bedser were treacherous. Australia went on to end on 509 and take a 344-run first innings lead.

Although Lindwall was able to run between the wickets during Australia's innings, he did not take the field in the second innings and the 12th man Neil Harvey replaced him. However, Yardley was sceptical as to whether Lindwall was sufficiently injured to be forced from the field, but did not approach Bradman to object to Harvey's presence on the field. O'Reilly said that as Lindwall demonstrated his mobility during his innings, he was in no way "incapacitated" and that the English captain "must be condemned for carrying his concepts of sportsmanship too far" when no substitute was justified.

After lunch on day four, with England on 3/191, the light was poor with clouds gathering, although England did not appeal against it. Yardley wanted to bat in poor visibility so that he could build a lead, so that if a shower came later and turned the pitch into a sticky wicket, Australia would have to chase a target on an erratic surface. Bradman thought that rain might come so he utilised Ernie Toshack and Ian Johnson to bowl defensively with a leg side field so that England would not have a lead should rain and a sticky wicket arise. Wisden opined that "rarely can a Test Match have been played under such appalling conditions as on this day". Fingleton said the conditions were "pitiable" and "utmost gloom in which batsmen and fieldsmen had intense difficulty in sighting the ball". Australia eventually finished off the hosts' second innings for 441, leaving them a target of 98 on the final afternoon. Late in England's innings, Bradman raised eyebrows by deliberately giving centurion Denis Compton easy singles by spreading his fielders in order to bring Evans on strike so that he could be targeted. Compton thought that Evans could be relied upon and readily accepted the runs gifted to him by the Australian captain, and Evans continued to play confidently, eventually reaching 50.

Australia proceeded steadily to 38 from 32 minutes before Morris fell. Bradman came to the crease and stayed 12 minutes without getting off the mark. He was out for a duck from the 10th ball that he faced, caught again by Hutton at short fine leg in Bedser's leg trap. Bradman showed obvious displeasure at allowing himself to be dismissed by the same trap in consecutive innings, and his departure left Australia at 48/2. It was the first time in four tours to England that Bradman had made a duck in a Test. This left Australia 2/48, but they reached the target without further loss after 87 minutes of batting.

Between Tests, Bradman rested himself during the match against Northamptonshire, which started the day after the Test, as Hassett led Australia to victory by an innings. He returned for the match against Yorkshire. Bradman came in at 1/0 when Barnes fell for a duck and top-scored with 54 as Australia made 249. Bradman pulled many short balls and reached 50 in 76 minutes. After the hosts replied with 209, Bradman came in at 1/17 and put on 154 for the second wicket with Brown, ending with 86 as the match petered into a draw. His innings ended when Hutton caught him in the leg trap. Not wanting to tire his bowlers before the Second Test that started the day after next, Bradman showed little intent to win the match. The batsmen batted unhurriedly and set Yorkshire 329 for victory with only 70 minutes of play remaining and the hosts ended at 4/85. Yardley expressed his displeasure by allowing his part-timers to bowl and then promoting tail-enders to the upper half of the batting order in the second innings. The Australians were booed from the field by the spectators.

Second Test

Main article: Second Test, 1948 Ashes seriesBradman opted to field an unchanged lineup for the Second Test, which started on 24 June at Lord's. Following his injury in the previous Test, Lindwall was subjected to a thorough fitness test on the first morning. Bradman was not convinced of Lindwall's fitness, but the bowler's protestations were sufficient to convince his captain to gamble on his inclusion. Bradman won the toss and elected to bat, allowing Lindwall further time to recover. Miller played, but was unfit to bowl.

Barnes fell for a duck in his second over, bringing Bradman to the crease at 1/3. Bradman received a loud reception from the crowd as he came out to bat in his final Test at Lord's. Bradman initially struggled against the English bowling. He faced his first ball from Alec Coxon and inside edged it past his leg stump, before missing the third ball from Coxon and surviving an appeal for leg before wicket (lbw). Bowling from the other end, Bedser beat Bradman with seam movement off the pitch and the ball narrowly skimmed past the stumps. Standing up to the stumps, wicket-keeper Godfrey Evans removed the bails as Bradman leaned forward, but his foot had stayed firmly behind the crease. In another close call, Bradman inside edged a ball towards Yardley at short leg, but the English captain was slow to react and the ball landed in front of him. The Australian captain managed only three runs in the first twenty minutes as Australia had only 14 after the first half-hour. Coxon consistently moved the ball into a cautious Bradman, and the Australians scored only 32 runs in the first hour.

Edrich came on and bowled a bouncer, which Bradman tried to swing to the leg side, but instead the edge went in the air and landed behind point. On 13, Bradman played a Bedser ball from his legs, narrowly evading Hutton in the trap at short fine leg. After one hour he was on 14. Bradman and Morris settled down as Coxon and Doug Wright operated. The Australian captain drove the debutant Coxon through the covers for two fours, and Yardley made frequent rotations of his bowlers. At the lunch break, Australia were 1/82 with Morris on 45 and Bradman 35. Shortly afterwards, in the third over after the resumption of play, with the score at 87, Bradman was caught for 38 for the third consecutive time in Tests by Hutton off Bedser at short fine leg, just two days after falling the same way in the second innings against Yorkshire. According to O'Reilly, this was evidence that Bradman was no longer the player he was before World War II, as he had been unable to disperse the close-catching fielders by counter-attacking, before eventually being dismissed. O'Reilly said that this was the first time that Bradman had fallen to the same trap three times in succession. Australia reached 7/258 at the end of day one, before a lower order burst took them to 350 on the second morning.

England then started their reply, and Lindwall took the new ball and felt pain in his groin again after delivering his first ball to Hutton. Despite this, Lindwall persevered through the pain. Seeing that Lindwall was able to bowl through the pain, Bradman tossed the ball to Miller for the second over to see if Miller could bowl. However, Miller threw the ball back, indicating that his body would not be able to withstand it. This resulted in media consternation that Bradman and Miller had quarrelled.

Although Bradman claimed that the exchange had been amicable, others disputed this. Teammate Barnes later claimed that Miller had retorted by suggesting that Bradman—a very occasional slower bowler—bowl himself. Barnes said that the captain "was as wild as a battery-stung brumby" and warned his unwilling bowler that there would be consequences for his defiance. According to unpublished writings in Fingleton's personal collection, Bradman chastised his players in the dressing room at the end of the play, saying "I'm 40 and I can do my full day's work in the field." Miller reportedly snapped "So would I—if I had fibrositis"; Bradman had been discharged from the armed services during World War II on health grounds, whereas most of the team had been sent into battle. Miller had crash-landed while serving as a fighter pilot in the Royal Australian Air Force in England and had suffered chronic back trouble since then.

On the second afternoon, Bradman delayed the taking of the second new ball until after tea so that Lindwall and Johnston could have an extra period of recuperation before a new attack. This proved dividends as the bowlers took a wicket apiece within three overs of the new ball being taken, leaving England at 6/134. England were bowled out for 215 on the third morning, as Lindwall took 5/70. In later years, Bradman told Lindwall that he pretended not to notice Lindwall's pain. Lindwall was worried that Bradman had noticed his injury, but Bradman later claimed that he feigned ignorance to allow Lindwall to relax. Australia batted much more productively in the second innings in ideal weather on the third day. Morris and Barnes put on 122 before the former fell for 62. Bradman joined Barnes at the crease for his last Test innings at the home of cricket. Yardley surrounded the Australian captain with fielders and Laker then beat his bat thrice in an over. Bedser was then introduced with the leg trap ploy again in place as he bowled on Bradman's pads. The Australian captain decided to negate the danger of being caught glancing at short fine leg by padding the ball away with his front leg. Bedser responded by changing his tactics by bowling a series of outswingers, beating the outside edge of Bradman's bat three times in a row, narrowly missing the off stump on one occasion. Barnes then manipulated the strike to shield his captain from Bedser. The Australian opener had little trouble against the leg trap, and negated the danger Bedser was posing. Bradman accelerated after tea and took two consecutive boundaries from Wright to bring up his fifty, with Barnes on 96 and Australia at 1/222.

Barnes passed his century and began accelerating before finally falling for 141, leaving Australia at 2/296 in 277 minutes, after a 174-run partnership with Bradman. Hassett was bowled first ball off the inside edge, but Miller survived a loud lbw appeal on Yardley's hat-trick ball. Bradman was on 89 and heading towards a century in his last Test innings at Lord's when he fell to Bedser again, this time because of a one-handed diving effort from Edrich. Bradman had been worried by Bedser's angle into his pads and the leg trap, but Bedser then moved the ball the other way towards the slips and caught Bradman's outside edge. It was the fourth time out of four innings in the series that Bedser had dismissed Bradman. This left Australia at 4/329 and the next day, Bradman was expected to declare just before lunch so that he could attack the English openers for a short period before the adjournment, but a shower at this time deterred him from doing so, as his bowlers would have struggled to grip the ball; Lindwall had also been injured on a slippery surface in earlier times. The Australian captain declared on the following day of play at 7/460, 595 runs ahead. It would take a world record chase from England to win the match. England lost wickets regularly and fell for 186 to lose by 409 runs.

The next match was against Surrey and started the day after the Test. Australia elected to field and the hosts made 221. Brown injured a finger while fielding, and was not able to bat in Australia's first innings. Ron Hamence filled in as an opener but was out for a duck, so Bradman joined Hassett at 1/6. Bradman made 128 and put on 231 with Hassett (139) as Australia replied with 389. Bradman's innings took only 140 minutes with 15 fours and was described by Jack Fingleton as "lovely". In the second innings, Australia's makeshift openers Harvey and Sam Loxton chased down the 122 runs for victory to complete a 10-wicket win. Australia wanted to finish the run-chase quickly so they could watch the Australian tennis player John Bromwich compete at Wimbledon and after Bradman had accepted Harvey's offer to open, Australia made the runs in only one hour. Bradman rested himself in the following match against Gloucestershire before the Third Test. Hassett led the team as Australia reached 7/774 declared, its highest of the tour, underpinning an innings victory.

Third Test

Main article: Third Test, 1948 Ashes seriesThe teams reassembled at Old Trafford on 8 July for the Third Test. Australia dropped Brown, who had scored 73 runs at 24.33 in three innings; he was replaced by the all rounder Sam Loxton, who had made 47 not out against Surrey and an unbeaten 159 against Gloucestershire. Yardley won the toss and elected to bat.

On the second day, Bradman was involved in effecting a run out. Denis Compton hit a ball into the covers and Bradman and Loxton collided in an attempt to prevent a run. Compton called Bedser through for a run on the misfield, but Loxton recovered and threw the ball to the wicket-keeper's end with Bedser a long way short of the crease. It ended an innings of 145 minutes, in which Bedser scored 37 and featured in a 121-run partnership with Compton. Compton hit several boundaries and Bradman responded by spreading his field to offer Compton a single so that the tail-enders would be on strike and could be attacked. This worked, as Compton was unable to farm the strike as he desired, and wickets fell at the other end. Bradman caught Jack Young to end England's innings at 363. Having dropped Brown, Barnes was hit in the ribs by a Dick Pollard pull shot and taken to hospital, leaving Australia with only Morris as a specialist opening batsman. Ian Johnson was deployed as Australia's makeshift second opener. He fell for one to bring Bradman to bat. O'Reilly criticised the use of Johnson to partner Morris, as Hassett had transformed himself into a defensive batsman with little backlift and a guarded approach, a style typical of an opener. The Australian captain thus had to face Bedser, who had already dismissed him three times in the Tests with a new ball, and Pollard, who had troubled him in the match against Lancashire. Pollard then trapped Bradman for seven with an off cutter that struck the Australian captain on the back foot to leave Australia at 2/13. Australia were eventually out for 221, yielding a 142-run lead.

When Bill Edrich came to the crease, Bradman advised Lindwall not to bowl any bouncers at Edrich, fearing that it would be interpreted as retaliation for Edrich's bouncing of Lindwall in the first innings and lead to a negative media and crowd reaction. Although Lindwall did not retaliate, Miller did so with four consecutive bouncers, earning the ire of the crowd. He struck Edrich on the body before Bradman intervened and ordered him to stop, before apologising to Edrich. England reached 3/174, a lead of 316, at the end of day three, but declared on the fifth morning after the fourth day was washed out. Bradman chose the light roller and play was supposed to begin after lunch. However, play did not begin until after tea and the pitch played very slowly because of the excess moisture. With Australia not looking to chase the runs, Yardley often had seven men in close catching positions. Australia showed little attacking intent and Bradman joined Morris with Australia at 1/10 after 32 minutes.

Bradman then played 11 balls from Young without scoring. Yardley used the spin of Young and Compton for an hour, while Morris and Bradman made little effort to score. For 105 minutes, Morris stayed at one end and Bradman at the other; neither looked to rotate the strike with singles. Bradman only played eight balls from Morris's main end, and at one point was so startled that Morris wanted a single that he sent him back. The tourists thereafter batted safely in a defensive manner to ensure a draw. They ended at 1/92 in 61 overs, a run rate of 1.50, with 35 maidens, which was the slowest innings run rate to date in the series. Bradman finished unbeaten on 30 from 146 balls when the oft-interrupted match was finally terminated by a series of periodic rain interruptions. O'Reilly criticised the approach taken by the Australians in the closing stages of the match, attributing it to Bradman's orders. He said that the pitch was made so tame by the heavy rain that they could have played in a natural and attractive manner to entertain the spectators, rather than defending carefully. He said that Bradman's "unwillingness to take a risk or to accept the challenging call of some particular phase of the game is one of the greatest flaws" in his leadership.

After the Test, Bradman managed only six as Australia scored 317 and 0/22 to defeat Middlesex by ten wickets in their only county match between Tests. He was again caught in the leg trap by Denis Compton.

Fourth Test

Main article: Fourth Test, 1948 Ashes seriesThe Fourth Test was played at Headingley, starting on 22 July, and Australia made two changes. Harvey replaced the injured Sid Barnes, while Ron Saggers replaced Don Tallon, who had a finger injury, as wicket-keeper. Brown was not recalled for the Fourth Test to open; instead, Hassett was promoted to open with Morris, while the teenaged Harvey came into the middle-order. As Australia were leading 2–0 after three Tests, England needed to win the last two Tests to square the series. England won the toss and elected to bat on an ideal batting pitch.

At the start of the innings, Bradman used off theory, but left a large gap square of the wicket in an attempt to coax England's out-of-form top-order to play risky shots into the inviting gap. However, Bradman's offer was spurned as Hutton and Washbrook played cautiously. Meanwhile, Australia's attack appeared unsettled. Bradman set defensive fields for most of the first day as England's openers put on 168 for the first wicket. O'Reilly said that Bradman's defensive field settings "made the sorry admission of impotency". England's batsmen dominated to reach stumps at 2/268. Jack Fingleton said that Australia's day went "progressively downhill" and was its worst day of bowling since the Second World War, citing the proliferation of full tosses. O'Reilly criticised the display as the worst by the Australians on tour and said that no bowler could be excused. He said that the attack "functioned without object—hopelessly and meaninglessly" throughout the day. He lambasted the bowlers for performing at a standard akin to county cricket. O'Reilly criticised the players for having a casual and lethargic manner, speculating that Bradman had been allowed them to become complacent.

On the second day, Bradman continued to use defensive tactics for most of the day as England continued to dominate. Australia had trouble removing night-watchman Bedser, who helped take the score to 2/423. Bradman gave his leading bowler Lindwall a heavy workload as the other bowlers appeared unthreatening. O'Reilly decried the use of Lindwall as excessive and potentially harmful to his longevity. The hosts were eventually out for 496, their largest score of the series, after a largely self-inflicted collapse late on the second day. Bedser removed Morris for six to leave Australia at 1/13. This brought Bradman to the crease and he was mobbed by the spectators on a ground where he had previously scored two triple centuries and another century in three Tests at the venue. He had made a Test world record of 334 in 1930, scoring 309 in one day's play. Many spectators walked onto the playing arena to greet the arrival of Bradman and he doffed his baggy green and raised his bat to greet them. Fingleton opined that "on this field he has won his greatest honours; nowhere else has he been so idolatrously acclaimed". Bradman got off the mark from his first ball, which Compton prevented from going for four with a diving stop near the boundary. Hassett was restrained, while Bradman attacked, taking three fours from one Edrich over. Bradman was 31 and Hassett 13 as the tourists reached stumps at 2/63. Bradman did the majority of the scoring in the late afternoon, scoring 31 in a partnership of 50.

On the third morning, Bradman resumed proceedings by taking a single from a Bedser no-ball. In same over, one ball reared from the pitch and moved into Bradman, hitting him in the groin, causing a delay as he recovered from the pain and recomposed himself before play resumed. In the second over bowled by Pollard, Hassett fell for 13 on the second ball, which lifted suddenly after bouncing. Miller came to the crease and drove his first ball for three runs, bringing Bradman on strike for the fourth ball of the over. Pollard then pitched a ball in the same place as he did to Hassett, but this time it skidded off the pitch and knocked out Bradman's off stump for 33. According to O'Reilly, Bradman backed away from the ball as it cut off the pitch with a noticeable flinch. O'Reilly attributed Bradman's unwillingness to get behind the ball to the blow inflicted on him by Bedser in the previous over and the rearing ball that dismissed Hassett. The crowd, sensing the importance of the two quick wickets, in particular that of Bradman, who had been so productive at Headingley, erupted. This left Australia struggling at 3/68, but a rapid counterattack by the middle and lower order took them to 9/457 at stumps and eventually 458 on the fourth morning.

England batted for the second time, and after lunch on the fourth afternoon, Bradman set fields to restrict the scoring, as England passed 100 without loss. Washbrook then hooked Johnston and top edged it, but Bradman failed to take the catch. He repeated the shot soon after and Harvey took the catch at 1/129, so the Australian captain's miss cost little. Johnson then removed Hutton for 57 without further addition to the total, caught by Bradman on the run, leaving England at 2/129. During most of the afternoon, Bradman used a strategy of rotating his bowlers in short spells, and set a defensive, well-spread field for Johnson, who had been repeatedly attacked by the batsmen. England then reached 8/362 at the close, a lead of 400. England batted on for five minutes on the final morning, adding three runs in two overs before Yardley declared at 8/365. As the batting team is allowed to choose which (if any) roller can be used at the start of the day's play, this ploy allowed Yardley to ask the groundsman to use a heavy roller, which would help to break up the wicket and make the surface more likely to spin. Bradman had done a similar thing during the previous Ashes series in Australia in order to make the batting conditions harder for England. At the start of any innings, the batting captain also has the choice of having the pitch rolled. Bradman elected to not have the pitch rolled at all, demonstrating his opinion that such a device would disadvantage his batsmen. This left Australia to chase 404 runs for victory. At the time, this would have been the highest ever fourth innings score to result in a Test victory. Australia had only 345 minutes to reach the target, and the local press wrote them off, predicting that they would be dismissed by lunchtime on a deteriorating spinners' wicket. Morris and Hassett started slowly, with only six runs in the first six overs on a pitch that offered spin and bounce. Only 44 runs came in the first hour, leaving 360 runs needed in 285 minutes. Both players survived close calls before Hassett fell at 1/57.

Bradman joined Morris with 347 runs needed in 257 minutes. After receiving another rapturous welcome from the Headingley spectators, Bradman signalled his intentions by hitting a boundary from Compton; and then, on his first ball from Laker, cover driving against the spin for a boundary. He reached 12 in six minutes. Yardley then called upon the occasional leg spin of Hutton in an attempt to exploit the turning wicket. Morris promptly joined Bradman in the counter-attack, and 20 runs in two Hutton overs, which Fingleton described as "rather terrible" due to the errant length. Bradman took two fours off Hutton's second over before almost holing out to Yardley. This let Australia reach 1/96 from 90 minutes.

In the next over, Compton deceived Bradman with a googly. Bradman expected the ball to turn in, but it went the other way, took the outside edge and ran away past slip for four. Bradman leg-glanced the next one for another boundary, before again failing to read a googly on the third ball. This time the edge went to Crapp, who failed to hold on. The sixth ball of Compton's over beat Bradman and hit him on the pads. At the other end, Morris continued to plunder Hutton's inaccurate leg breaks, and Australia reached lunch at 1/121, with Morris on 63 and Bradman on 35. Hutton had conceded 30 runs in four overs, and in the half-hour preceding the interval, Australia had added 64 runs. Both players had been given lives. Although Australia had scored at a reasonable rate, they had also been troubled by many of the deliveries and were expected to face further difficulty if they were to avoid defeat.

After the break, Morris added 37 runs in 14 minutes from a series of Compton full tosses and long hops, while Bradman had only added three. This prompted Yardley to take the new ball. Bradman reached 50 in 60 minutes and then aimed a drive from Ken Cranston, but sliced it in the air to point. Yardley dived and got his hands to the ball, but failed to hold on. Australia reached 202—halfway to the required total—with 165 minutes left, after Morris dispatched consecutive full tosses from Laker. Bradman then hooked two boundaries, but suffered a fibrositis attack, which put him in significant pain. Drinks were then taken, and Morris had to farm the strike until Bradman's pain had subsided. Australia then reached 250 shortly before tea with Morris on 133 and Bradman on 92. Bradman then reached his century in 147 minutes as the second-wicket stand passed 200.

Bradman was given another life at 108 when he advanced two metres down the pitch to Jim Laker and missed, but Evans fumbled the stumping opportunity. Australia reached tea at 1/292 having added 171 during the session. Morris was eventually dismissed for 182, having partnered Bradman in a stand of 301 in 217 minutes. This brought Miller to the crease with 46 runs still required. He struck two boundaries and helped take the score to 396 before falling with eight runs still needed. Harvey came in and got off the mark with a boundary that brought up the winning runs. This sealed an Australian victory by seven wickets, setting a new world record for the highest successful Test run-chase, with Bradman unbeaten on 173 with 29 fours in only 255 minutes.

Immediately after the Fourth Test, Bradman scored 62, before being bowled attempting a pull shot to a ball that kept low, as Australia compiled 456 and defeated Derbyshire by an innings. Bradman rested himself in the next match against Glamorgan, a rain-affected draw that did not reach the second innings. He then scored 31 and 13 not out, bowled by Eric Hollies as Australia defeated Warwickshire by nine wickets. Hollies's 8/107 was the best innings bowling figures against the Australians for the summer and earned him selection for the Fifth Test, where he famously dismissed Bradman in his final Test innings for a duck. Australia proceeded to face and draw with Lancashire for the second time on the tour. Bradman made 28 after being dropped twice in Australia's 321, before taking two catches as the tourists took a 191-run lead. He then came in at 1/16 and put on 161 for the second wicket with Barnes, and was unbeaten on 133 when he declared at 3/265. The home side hung on for a draw at 7/199 when time ran out. Bradman then rested himself during the non-first-class match against Durham, a rain-affected draw that was washed out after the first day.

Fifth Test

Main article: Fifth Test, 1948 Ashes seriesAfter the match against Durham, Australia headed south to The Oval for the Fifth Test, which started on 14 August. Barnes and Tallon returned from injury, while Ernie Toshack was omitted with knee troubles, and the leg spin of Doug Ring replaced Johnson's off spin. Overnight, hundreds of spectators had slept on wet pavements in rainy weather to queue for tickets. Bradman had already announced that he would retire at the end of the season, and the public were anxious to witness his last Test appearance.

English skipper Norman Yardley won the toss and elected to bat on a rain-affected pitch. Yardley's decision was regarded as a surprise; although The Oval had traditionally been a batting paradise, weather conditions suggested that bowlers would have the advantage. Jack Fingleton speculated that Australia would have bowled first if Bradman had won the toss. Propelled by Lindwall's 6/20, England were dismissed for 52 in 42.1 overs on the first afternoon.

In contrast, Australia batted much more fluently as the overcast skies cleared and the sun came out. Australia had reached 100 at 17:30 with Barnes on 52 and Morris on 47. The score had reached 117 before Barnes was removed by Hollies for 61. This brought Bradman to the crease shortly before 18:00, late on the first day. As Bradman had announced that the tour was his last at international level, the innings would be his last at Test level if Australia batted only once. The crowd gave him a standing ovation as he walked out to bat. Yardley led the Englishmen in giving his Australian counterpart three cheers before shaking Bradman's hand. With 6996 Test career runs, he only needed four runs to average 100 in Test cricket. Bradman took guard and played the first ball from Hollies from the back foot. Hollies pitched the next ball up, bowling Bradman for a duck with a googly that went between bat and pad as the batsman leaned forward. Bradman appeared stunned by what had happened and slowly turned around and walked back to the pavilion, receiving another large round of applause. Australia went on to make 389 and then bowled England out for 188 to win by an innings and 149 runs.

This result sealed the series 4–0 in favour of Australia. The match was followed by a series of congratulatory speeches.

Bradman said

No matter what you may read to the contrary, this is definitely my last Test match ever. I am sorry my personal contribution has been so small ... It has been a great pleasure for me to come on this tour and I would like you all to know how much I have appreciated it ... We have played against a very lovable opening skipper ... It will not be my pleasure to play ever again on this Oval but I hope it will not be the last time I come to England.

Yardley said

In saying good-bye to Don we are saying good-bye to the greatest cricketer of all time. He is not only a great cricketer but a great sportsman, on and off the field. I hope this is not the last time we see Don Bradman in this country.

Bradman was then given three cheers and the crowd sung "For he's a jolly good fellow" before dispersing.

Later tour matches

Seven matches remained on Bradman's quest to complete an English season without defeat. Australia batted first against Kent and Bradman made 65, putting on 104 with Brown as Australia made 361 and won by an innings. In the next match against the Gentlemen of England, Bradman came to the crease at 1/40 and featured in a 180-run second wicket partnership with Brown, before adding another 110 with Hassett. He was out for 150 at 3/331 before declaring at 5/610 against a team that included eight Test players. Australia went on to win by an innings. He then rested himself as Australia defeated Somerset by an innings and 374 runs. Bradman returned to make 143 against the South of England, adding 188 for the third wicket with Hassett. Australia declared at 7/522 and bowled out the hosts for 298 before rain ended the match.

Australia's biggest challenge in the post-Test tour matches was against the Leveson-Gower's XI starting on 8 September, its last first-class match for the tour. During the last tour in 1938, this team was effectively a full-strength England outfit and had defeated Australia, but this time Bradman insisted that only six current Test players be allowed to represent the hosts. Bradman then fielded a full-strength team; the only difference from the Fifth Test team was Johnson's inclusion at the expense of Ring. His bowlers skittled the hosts for 177, and Morris and Barnes put on an opening stand of 102 before Morris was out for 62. Bradman joined Barnes and they put on 225 runs for the second wicket. Bradman top-scored with 153 as Australia declared at 8/469 late on the final day. Upon reaching 153, he threw away his wicket with a lofted cover drive, having decided to attempt sixes to give Alec Bedser his wicket. He was already running towards the pavilion before the catch was taken, ending his last first-class innings in England. The hosts were 2/75 when the match ended in a draw after multiple rain delays. When it became obvious that Australia would not lose, Bradman bowled his only over of the tour, conceding two runs.

The tour ended with two non-first-class matches against Scotland. In the first match, Bradman made 27 of Australia's 236 as the tourists took an innings victory. In the second match, Bradman top-scored with 123 not out batting at No. 6, hitting 17 fours and two sixes in 89 minutes as Australia declared at 6/407. Australia ended the tour with another innings victory. Once Australia were in an unassailable position during Scotland's second innings, Bradman relaxed and allowed nine players to bowl, including the wicket-keeper Tallon, who took two wickets, while Johnson stood in as the wicket-keeper. When the victory was sealed on 18 September, Bradman's men became the first side to go through an English season without defeat.

Role

Along with Chappie Dwyer and Jack Ryder, Bradman was one of the three selectors who chose the squad to tour England. This gave Bradman more power than other Australian captains, who did not have an explicit vote in team selection. This was further magnified by Bradman being a member of the Board of Control while an active player, a threefold combination that he alone has occupied in Australian cricket history. According to Gideon Haigh, he "was the dominant figure in Australian cricket", who went on to become an "unimpeachable figure".

Turning 40 in August during the tour, Bradman was by far the most senior and oldest player on the team. Bill Brown was the next oldest, making his third tour of England at 36. His vice-captain Lindsay Hassett was the third-oldest player, at the age of 35. Ernie Toshack was born in December 1914, and the remaining 13 players were born in 1916 or later. Five players, including Ray Lindwall, Bill Johnston and Morris, his two most prolific Test bowlers and batsman respectively, were more than 12 years younger than he was. Neil Harvey, the youngest player at the age of 19, was only two months old when Bradman made his Test debut. Bradman was viewed as a father figure by players such as Harvey and Sam Loxton. Before the tour, Bradman had played 47 Tests; Brown, the only other member who had played regularly before the Second World War, had appeared in 20 Tests. For Bradman, it was the most personally fulfilling period of his playing days, as the divisiveness within the team of the 1930s had passed. He wrote:

Knowing the personnel, I was confident that here at last was the great opportunity which I had longed for. A team of cricketers whose respect and loyalty were unquestioned, who would regard me in a fatherly sense and listen to my advice, follow my guidance and not question my handling of affairs ... there are no longer any fears that they will query the wisdom of what you do. The result is a sense of freedom to give full reign to your own creative ability and personal judgment.

However, some players expressed displeasure at Bradman's ruthless obsession towards annihilating the opposition. The all rounder Keith Miller, who was one of two bowling spearheads, deliberately allowed himself to be bowled first ball for duck during the match against Essex, while Bradman was his batting partner, in a protest against Australia's world record of scoring 721 runs in one day. Miller also deplored Bradman's hard-nosed attitude in the match against Leveson-Gower's XI, which was traditionally regarded as a "festival match". Feeling that Bradman was needlessly batting Australia far beyond impregnability, Miller played with reckless aggression, rather than a measured style in line with Bradman's aim of remaining undefeated. Bradman's later letter revealed his hostility towards Miller. Sid Barnes later criticised Bradman for his reluctance to allow Ron Hamence—one of the reserve batsmen—to partake in meaningful matchplay; due to Bradman's reluctance to risk Australia's unbeaten run, Hamence usually batted low in the order and had limited opportunities because the senior batsmen were rarely dismissed cheaply. Along with fringe bowlers Doug Ring and Colin McCool, Hamence called himself "Ground Staff" due to the trio's lack of on-field duties, and they often sang ironic songs about their status.

Bradman's relentless use of his pace attack and fieldsmen also raised eyebrows. At the time, Lindwall and Miller were groundbreaking fast bowlers, with high pace and the ability to deliver menacing short-pitched bowling at the upper body of the English batsmen. Prior to the Second World War, pace bowlers were generally much slower and did not often bowl at the body. England had yet to develop bowlers such as Lindwall and Miller, and as a result, Australia were able to pepper the upper body of the opposition without fear of retaliation. At times, the public found Lindwall and Miller's short-pitched bowling to be excessive and booed the Australians. On the fielding front, Barnes was deployed as close to the bat as possible at either forward short-leg or point, with one foot on the pitch. This had an intimidatory effect on the batsmen and led many to question whether it was in the spirit of the game.

Bradman's dominant cricketing stature was also a key platform of his team's popularity with the public. The leading English writer R. C. Robertson-Glasgow said "we want him to do well. We feel we have a share in him. He is more than Australian. He is a world batsman." Haigh opined that "perhaps no touring cricketer ... has been as feted as Bradman in that northern summer". The Australians were invariably greeted by record crowds and gate receipts across the country. The attendance at the Fourth Test remains a record for a Test on English soil. The Australian journalist Andy Flanagan said that "cities, towns and hotels are beflagged, carpets set down, and dignitaries wait to extend an official welcome. He is the Prince of Cricketers." Haigh said that "cricket approached the 50s at the peak of its popularity, albeit, after Bradman's final Test ... without the player chiefly responsible for it". Bradman received hundreds of personal letters every day, and one of his dinner speeches was broadcast live, causing the British Broadcasting Corporation to postpone the news bulletin. Of Bradman's retirement, Robertson-Glasgow said "... a miracle has been removed from among us... So must ancient Italy have felt when she heard of the death of Hannibal."

Bradman ended the first-class matches atop the batting aggregates and averages, with 2428 runs at 89.92, and eleven centuries, the most by any player. The next most prolific scorer was Morris with 1922 runs, and Hassett had the next best average with 74.42. His highest score of the tour was 187 against Essex, and he reached 150 on four occasions. Despite his success, he also gained attention for his troubles against Alec Bedser's leg trap; Bradman was dismissed three consecutive times in the Tests in this manner, and twice outside the Tests to other bowlers using the same ploy. Robertson-Glasgow said "at last his batting showed human fallibility. Often, especially at the start of the innings, he played where the ball wasn't, and spectators rubbed their eyes". In the Tests, Bradman finished with 508 runs at 72.57 and two centuries. Only Morris and Barnes averaged higher and only Morris and Denis Compton of England aggregated more. Apart from the match against Leicestershire, when he batted at No. 4, and the two non-first-class matches against Scotland, Bradman always batted at No. 3. He bowled only one over during the tour, against the Leveson-Gower's XI when the result of the match was beyond doubt.

Notes

Statistical note

n- This statement can be verified by consulting all of the scorecards for the matches, as listed here.

General notes

- This notation means that three wickets were lost in the process of scoring 404 runs.

- ^ Stephens, Tony (18 January 2003). "Why the Don nearly declined invincibility". The Age. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- ^ Perry (2005), pp. 222–225.

- ^ "1st Test England v Australia at Nottingham Jun 10-15 1948". Cricinfo. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- ^ "2nd Test England v Australia at Lord's Jun 24–29 1948". Cricinfo. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- ^ "3rd Test England v Australia at Manchester Jul 8-13 1948". Cricinfo. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- ^ "4th Test England v Australia at Leeds Jul 22-27 1948". Cricinfo. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- ^ "5th Test England v Australia at The Oval Aug 14–18 1948". Cricinfo. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- ^ Haigh, Gideon (26 May 2007). "Gentrifying the game". Cricinfo. Retrieved 1 June 2007.

- ^ "Worcestershire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Fingleton, pp. 46–47.

- ^ "Leicestershire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Fingleton, p. 49.

- ^ "Matches, Australia tour of England, Apr-Sep 1948". Cricinfo. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ "Player Oracle DG Bradman 1948". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Fingleton, pp. 53–55.

- ^ "Yorkshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Fingleton, pp. 53–57.

- Fingleton, p. 57.

- ^ "Surrey v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Fingleton, pp. 59–60.

- ^ "Cambridge University v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- ^ "Essex v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- "Player Profile: Frank Vigar". CricInfo. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 67.

- ^ Perry (2005), p. 226.

- ^ "Oxford University v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- ^ "MCC v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Fingleton, p. 72.

- Fingleton, p. 75.

- ^ "Lancashire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Fingleton, p. 76.

- ^ "Nottinghamshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- ^ "Hampshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Sussex v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 79.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 82.

- "Statsguru – Australia – Tests – Results list". Cricinfo. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- Perry (2002), p. 100.

- Fingleton, p. 87.

- ^ "First Test Match England v Australia". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. Wisden. 1949. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- ^ O'Reilly, p. 35.

- Fingleton, p. 90.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 91.

- O'Reilly, p. 38.

- ^ Arlott, p. 36.

- Perry (2005), p. 235.

- ^ O'Reilly, p. 39.

- Arlott, p. 37.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 92.

- Arlott, pp. 37–38.

- Arlott, p. 38.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 93.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 96.

- O'Reilly, p. 42.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 101.

- Fingleton, p. 103.

- ^ O'Reilly, p. 52.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 105.

- O'Reilly, p. 53.

- Arlott, p. 51.

- ^ "Northamptonshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Yorkshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- Fingleton, p. 193.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 109.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 195.

- ^ Perry (2001), p. 223.

- Perry (2001), p. 233.

- Perry (2005), p. 239.

- ^ "Second Test Match England v Australia". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. Wisden. 1949. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 108.

- O'Reilly, p. 60.

- ^ Arlott, p. 56.

- O'Reilly, p. 61.

- O'Reilly, p. 62.

- O'Reilly, p. 64.

- Perry (2005), p. 240.

- Growden, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Growden, p. 203.

- Perry (2005), pp. 105–120.

- O'Reilly, p. 71.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 116.

- O'Reilly, pp. 73–74.

- O'Reilly, p. 74.

- Fingleton, p. 117.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 118.

- ^ Perry (2005), p. 241.

- Fingleton, p. 120.

- O'Reilly, p. 76.

- "Australians in England, 1948". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack (1949 ed.). Wisden. pp. 237–238.

- ^ "Surrey v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Fingleton, p. 196.

- ^ "Gloucestershire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 136.

- Arlott, p. 87.

- ^ O'Reilly, p. 97.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 137.

- Perry (2005), p. 243.

- Perry (2005), p. 244.

- Fingleton, p. 143.

- Fingleton, p. 145.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 146.

- "Third Test Match England v Australia". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. Wisden. 1949. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- O'Reilly, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 200.

- Perry (2002), p. 101.

- Lemmon, p. 103.

- ^ "Fourth Test Match England v Australia". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. Wisden. 1949. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- O'Reilly, p. 113.

- Arlott, p. 99.

- ^ O'Reilly, p. 114.

- Fingleton, p. 152.

- Fingleton, p. 154.

- O'Reilly, p. 115.

- O'Reilly, p. 118.

- Fingleton, p. 158.

- ^ Fingleton, pp. 158–159.

- Cashman, pp. 20–30.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 159.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 160.

- ^ O'Reilly, p. 123.

- Fingleton, p. 169.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 170.

- O'Reilly, p. 135.

- Arlott, p. 114.

- Fingleton, p. 172.

- Fingleton, p. 173.

- ^ Perry (2001), pp. 84–89.

- ^ Pollard, p. 15.

- Fingleton, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 175.

- Fingleton, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 176.

- O'Reilly, p. 139.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 177.

- ^ "Derbyshire v Australians". CricketArchive. 28 July 1948. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Fingleton, pp. 204–205.

- Fingleton, p. 206.

- ^ "Lancashire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Durham v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Fifth Test Match England v Australia". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. Wisden. 1949. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 186.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 183.

- "Biographical essay by Michael Page". State Library South Australia. Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ^ Cashman, pp. 33–38.

- Fingleton, p. 187.

- ^ Fingleton, p. 191.

- ^ "Kent v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- ^ "Gentlemen v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- ^ Perry (2005), pp. 253–254.

- Fingleton, pp. 207–209.

- ^ "H.D.G. Leveson-Gower's XI v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Fingleton, p. 209.

- ^ "Scotland v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Scotland v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Perry (2005), pp. 159, 262.

- ^ Haigh and Frith, p. 100.

- Haigh and Frith, p. 88.

- Cashman, p. 33.

- ^ Cashman, p. 38.

- Cashman, p. 119.

- Cashman, p. 299.

- Cashman, pp. 14–15, 115, 152, 199, 212–213, 258–259, 267, 289.

- Cashman, pp. 153, 174, 176, 215–216, 118.

- Cashman, pp. 33, 118.

- Perry (2006), p. 168.

- Bradman (1950), p 152.

- Fingleton, p. 63.

- ^ Perry (2005), pp. 250–255.

- ^ Barnes, p. 180.

- "Player Oracle RA Hamence 1948". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Fingleton, pp. 125–130.

- Fingleton, p. 99.

- Fingleton, pp. 73–74.

- "Australians in England". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack (1949 ed.). Wisden. pp. 240–241.

- ^ Haigh and Frith, p. 101.

- ^ Robertson-Glasgow, R. C. (1949). "A Miracle Has Been Removed From Among Us". Wisden. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- ^ "Batting and bowling averages Australia tour of England, Apr-Sep 1948 – First-class matches". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- "Batting and bowling averages The Ashes, 1948 – Australia". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- "Batting and bowling averages The Ashes, 1948 – England". Cricinfo. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- "Middlesex v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- "Glamorgan v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- "Warwickshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- "South of England v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- "Somerset v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

References

- Arlott, John (1949). Gone to the test match : being primarily an account of the test series of 1948. London: Longmans.

- Barnes, Sid (1953). It Isn't Cricket. London and Sydney: Collins.

- Bradman, Donald (1950). Farewell to Cricket. London: Pavilion Library. ISBN 1-85145-225-7.

- Cashman, Richard; Franks, Warwick; Maxwell, Jim; Sainsbury, Erica; Stoddart, Brian; Weaver, Amanda; Webster, Ray (1997). The A–Z of Australian cricketers. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-9756746-1-7.

- Fingleton, Jack (1949). Brightly fades the Don. London: Collins.

- Growden, Greg (2008). Jack Fingleton : the man who stood up to Bradman. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-548-0.

- Haigh, Gideon; Frith, David (2007). Inside story:unlocking Australian cricket's archives. Southbank, Victoria: News Custom Publishing. ISBN 978-1-921116-00-1.

- Lemmon, David (1984). The great wicket-keepers. London: Stanley Paul. ISBN 0-09-155210-9.

- O'Reilly, W. J. (1949). Cricket conquest: the story of the 1948 test tour. London: Werner Laurie.

- Perry, Roland (2000). Captain Australia: A history of the celebrated captains of Australian Test cricket. Milsons Point, New South Wales: Random House Australia. ISBN 1-74051-174-3.

- Perry, Roland (2001). Bradman's best: Sir Donald Bradman's selection of the best team in cricket history. Milsons Point, New South Wales: Random House Australia. ISBN 0-09-184051-1.

- Perry, Roland (2002). Bradman's best Ashes teams : Sir Donald Bradman's selection of the best ashes teams in cricket history. Milsons Point, New South Wales: Random House Australia. ISBN 1-74051-125-5.

- Perry, Roland (2005). Miller's Luck: the life and loves of Keith Miller, Australia's greatest all-rounder. Milsons Point, New South Wales: Random House Australia. ISBN 978-1-74166-222-1.

- Perry, Roland (2006). The Ashes: a celebration. Milsons Point, New South Wales: Random House Australia. ISBN 1-74166-490-X.

- Pollard, Jack (1990). From Bradman to Border: Australian Cricket 1948–89. North Ryde, New South Wales: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-207-16124-0.

| Australia squad – The Invincibles | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||