The Doppler effect (also Doppler shift) is the change in the frequency of a wave in relation to an observer who is moving relative to the source of the wave. The Doppler effect is named after the physicist Christian Doppler, who described the phenomenon in 1842. A common example of Doppler shift is the change of pitch heard when a vehicle sounding a horn approaches and recedes from an observer. Compared to the emitted frequency, the received frequency is higher during the approach, identical at the instant of passing by, and lower during the recession.

When the source of the sound wave is moving towards the observer, each successive cycle of the wave is emitted from a position closer to the observer than the previous cycle. Hence, from the observer's perspective, the time between cycles is reduced, meaning the frequency is increased. Conversely, if the source of the sound wave is moving away from the observer, each cycle of the wave is emitted from a position farther from the observer than the previous cycle, so the arrival time between successive cycles is increased, thus reducing the frequency.

For waves that propagate in a medium, such as sound waves, the velocity of the observer and of the source are relative to the medium in which the waves are transmitted. The total Doppler effect in such cases may therefore result from motion of the source, motion of the observer, motion of the medium, or any combination thereof. For waves propagating in vacuum, as is possible for electromagnetic waves or gravitational waves, only the difference in velocity between the observer and the source needs to be considered.

History

Doppler first proposed this effect in 1842 in his treatise "Über das farbige Licht der Doppelsterne und einiger anderer Gestirne des Himmels" (On the coloured light of the binary stars and some other stars of the heavens). The hypothesis was tested for sound waves by Buys Ballot in 1845. He confirmed that the sound's pitch was higher than the emitted frequency when the sound source approached him, and lower than the emitted frequency when the sound source receded from him. Hippolyte Fizeau discovered independently the same phenomenon on electromagnetic waves in 1848 (in France, the effect is sometimes called "effet Doppler-Fizeau" but that name was not adopted by the rest of the world as Fizeau's discovery was six years after Doppler's proposal). In Britain, John Scott Russell made an experimental study of the Doppler effect (1848).

General

In classical physics, where the speeds of source and the receiver relative to the medium are lower than the speed of waves in the medium, the relationship between observed frequency and emitted frequency is given by: where

- is the propagation speed of waves in the medium;

- is the speed of the receiver relative to the medium. In the formula, is added to if the receiver is moving towards the source, subtracted if the receiver is moving away from the source;

- is the speed of the source relative to the medium. is subtracted from if the source is moving towards the receiver, added if the source is moving away from the receiver.

Note this relationship predicts that the frequency will decrease if either source or receiver is moving away from the other.

Equivalently, under the assumption that the source is either directly approaching or receding from the observer: where

- is the wave's speed relative to the receiver;

- is the wave's speed relative to the source;

- is the wavelength.

If the source approaches the observer at an angle (but still with a constant speed), the observed frequency that is first heard is higher than the object's emitted frequency. Thereafter, there is a monotonic decrease in the observed frequency as it gets closer to the observer, through equality when it is coming from a direction perpendicular to the relative motion (and was emitted at the point of closest approach; but when the wave is received, the source and observer will no longer be at their closest), and a continued monotonic decrease as it recedes from the observer. When the observer is very close to the path of the object, the transition from high to low frequency is very abrupt. When the observer is far from the path of the object, the transition from high to low frequency is gradual.

If the speeds and are small compared to the speed of the wave, the relationship between observed frequency and emitted frequency is approximately

| Observed frequency | Change in frequency |

|---|---|

where

- is the opposite of the relative speed of the receiver with respect to the source: it is positive when the source and the receiver are moving towards each other.

Given

we divide for

Since we can substitute using the Taylor's series expansion of truncating all and higher terms:

When substituted in the last line, one gets:

For small and , the last term becomes insignificant, hence:

-

Stationary sound source produces sound waves at a constant frequency f, and the wave-fronts propagate symmetrically away from the source at a constant speed c. The distance between wave-fronts is the wavelength. All observers will hear the same frequency, which will be equal to the actual frequency of the source where f = f0.

Stationary sound source produces sound waves at a constant frequency f, and the wave-fronts propagate symmetrically away from the source at a constant speed c. The distance between wave-fronts is the wavelength. All observers will hear the same frequency, which will be equal to the actual frequency of the source where f = f0.

-

The same sound source is radiating sound waves at a constant frequency in the same medium. However, now the sound source is moving with a speed υs = 0.7 c. Since the source is moving, the centre of each new wavefront is now slightly displaced to the right. As a result, the wave-fronts begin to bunch up on the right side (in front of) and spread further apart on the left side (behind) of the source. An observer in front of the source will hear a higher frequency f = c + 0/c – 0.7c f0 = 3.33 f0 and an observer behind the source will hear a lower frequency f = c − 0/c + 0.7c f0 = 0.59 f0.

The same sound source is radiating sound waves at a constant frequency in the same medium. However, now the sound source is moving with a speed υs = 0.7 c. Since the source is moving, the centre of each new wavefront is now slightly displaced to the right. As a result, the wave-fronts begin to bunch up on the right side (in front of) and spread further apart on the left side (behind) of the source. An observer in front of the source will hear a higher frequency f = c + 0/c – 0.7c f0 = 3.33 f0 and an observer behind the source will hear a lower frequency f = c − 0/c + 0.7c f0 = 0.59 f0.

-

Now the source is moving at the speed of sound in the medium (υs = c). The wave fronts in front of the source are now all bunched up at the same point. As a result, an observer in front of the source will detect nothing until the source arrives and an observer behind the source will hear a lower frequency f = c – 0/c + c f0 = 0.5 f0.

Now the source is moving at the speed of sound in the medium (υs = c). The wave fronts in front of the source are now all bunched up at the same point. As a result, an observer in front of the source will detect nothing until the source arrives and an observer behind the source will hear a lower frequency f = c – 0/c + c f0 = 0.5 f0.

-

The sound source has now surpassed the speed of sound in the medium, and is traveling at 1.4 c. Since the source is moving faster than the sound waves it creates, it actually leads the advancing wavefront. The sound source will pass by a stationary observer before the observer hears the sound. As a result, an observer in front of the source will detect nothing and an observer behind the source will hear a lower frequency f = c – 0/c + 1.4c f0 = 0.42 f0.

The sound source has now surpassed the speed of sound in the medium, and is traveling at 1.4 c. Since the source is moving faster than the sound waves it creates, it actually leads the advancing wavefront. The sound source will pass by a stationary observer before the observer hears the sound. As a result, an observer in front of the source will detect nothing and an observer behind the source will hear a lower frequency f = c – 0/c + 1.4c f0 = 0.42 f0.

Consequences

Assuming a stationary observer and a wave source moving towards the observer at (or exceeding) the speed of the wave, the Doppler equation predicts an infinite (or negative) frequency as from the observer's perspective. Thus, the Doppler equation is inapplicable for such cases. If the wave is a sound wave and the sound source is moving faster than the speed of sound, the resulting shock wave creates a sonic boom.

Lord Rayleigh predicted the following effect in his classic book on sound: if the observer were moving from the (stationary) source at twice the speed of sound, a musical piece previously emitted by that source would be heard in correct tempo and pitch, but as if played backwards.

Applications

Sirens

A siren on a passing emergency vehicle will start out higher than its stationary pitch, slide down as it passes, and continue lower than its stationary pitch as it recedes from the observer. Astronomer John Dobson explained the effect thus:

The reason the siren slides is because it doesn't hit you.

In other words, if the siren approached the observer directly, the pitch would remain constant, at a higher than stationary pitch, until the vehicle hit him, and then immediately jump to a new lower pitch. Because the vehicle passes by the observer, the radial speed does not remain constant, but instead varies as a function of the angle between his line of sight and the siren's velocity: where is the angle between the object's forward velocity and the line of sight from the object to the observer.

Astronomy

Main article: Relativistic Doppler effect

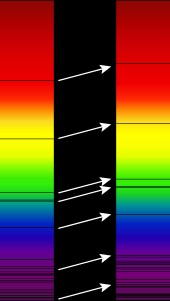

The Doppler effect for electromagnetic waves such as light is of widespread use in astronomy to measure the speed at which stars and galaxies are approaching or receding from us, resulting in so called blueshift or redshift, respectively. This may be used to detect if an apparently single star is, in reality, a close binary, to measure the rotational speed of stars and galaxies, or to detect exoplanets. This effect typically happens on a very small scale; there would not be a noticeable difference in visible light to the unaided eye. The use of the Doppler effect in astronomy depends on knowledge of precise frequencies of discrete lines in the spectra of stars.

Among the nearby stars, the largest radial velocities with respect to the Sun are +308 km/s (BD-15°4041, also known as LHS 52, 81.7 light-years away) and −260 km/s (Woolley 9722, also known as Wolf 1106 and LHS 64, 78.2 light-years away). Positive radial speed means the star is receding from the Sun, negative that it is approaching.

The relationship between the expansion of the universe and the Doppler effect is not simple matter of the source moving away from the observer. In cosmology, the redshift of expansion is considered separate from redshifts due to gravity or Doppler motion.

Distant galaxies also exhibit peculiar motion distinct from their cosmological recession speeds. If redshifts are used to determine distances in accordance with Hubble's law, then these peculiar motions give rise to redshift-space distortions.

Radar

Main article: Doppler radar

The Doppler effect is used in some types of radar, to measure the velocity of detected objects. A radar beam is fired at a moving target – e.g. a motor car, as police use radar to detect speeding motorists – as it approaches or recedes from the radar source. Each successive radar wave has to travel farther to reach the car, before being reflected and re-detected near the source. As each wave has to move farther, the gap between each wave increases, increasing the wavelength. In some situations, the radar beam is fired at the moving car as it approaches, in which case each successive wave travels a lesser distance, decreasing the wavelength. In either situation, calculations from the Doppler effect accurately determine the car's speed. Moreover, the proximity fuze, developed during World War II, relies upon Doppler radar to detonate explosives at the correct time, height, distance, etc.

Because the Doppler shift affects the wave incident upon the target as well as the wave reflected back to the radar, the change in frequency observed by a radar due to a target moving at relative speed is twice that from the same target emitting a wave:

Medical

Main article: Doppler ultrasonography

An echocardiogram can, within certain limits, produce an accurate assessment of the direction of blood flow and the velocity of blood and cardiac tissue at any arbitrary point using the Doppler effect. One of the limitations is that the ultrasound beam should be as parallel to the blood flow as possible. Velocity measurements allow assessment of cardiac valve areas and function, abnormal communications between the left and right side of the heart, leaking of blood through the valves (valvular regurgitation), and calculation of the cardiac output. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound using gas-filled microbubble contrast media can be used to improve velocity or other flow-related medical measurements.

Although "Doppler" has become synonymous with "velocity measurement" in medical imaging, in many cases it is not the frequency shift (Doppler shift) of the received signal that is measured, but the phase shift (when the received signal arrives).

Velocity measurements of blood flow are also used in other fields of medical ultrasonography, such as obstetric ultrasonography and neurology. Velocity measurement of blood flow in arteries and veins based on Doppler effect is an effective tool for diagnosis of vascular problems like stenosis.

Flow measurement

Instruments such as the laser Doppler velocimeter (LDV), and acoustic Doppler velocimeter (ADV) have been developed to measure velocities in a fluid flow. The LDV emits a light beam and the ADV emits an ultrasonic acoustic burst, and measure the Doppler shift in wavelengths of reflections from particles moving with the flow. The actual flow is computed as a function of the water velocity and phase. This technique allows non-intrusive flow measurements, at high precision and high frequency.

Velocity profile measurement

Developed originally for velocity measurements in medical applications (blood flow), Ultrasonic Doppler Velocimetry (UDV) can measure in real time complete velocity profile in almost any liquids containing particles in suspension such as dust, gas bubbles, emulsions. Flows can be pulsating, oscillating, laminar or turbulent, stationary or transient. This technique is fully non-invasive.

Satellites

|

|

|

Satellite navigation

Main article: Satellite navigationThe Doppler shift can be exploited for satellite navigation such as in Transit and DORIS.

Satellite communication

Main article: Satellite communicationDoppler also needs to be compensated in satellite communication. Fast moving satellites can have a Doppler shift of dozens of kilohertz relative to a ground station. The speed, thus magnitude of Doppler effect, changes due to earth curvature. Dynamic Doppler compensation, where the frequency of a signal is changed progressively during transmission, is used so the satellite receives a constant frequency signal. After realizing that the Doppler shift had not been considered before launch of the Huygens probe of the 2005 Cassini–Huygens mission, the probe trajectory was altered to approach Titan in such a way that its transmissions traveled perpendicular to its direction of motion relative to Cassini, greatly reducing the Doppler shift.

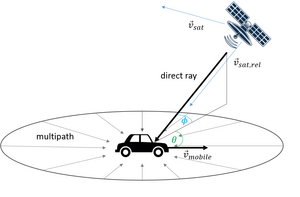

Doppler shift of the direct path can be estimated by the following formula: where is the speed of the mobile station, is the wavelength of the carrier, is the elevation angle of the satellite and is the driving direction with respect to the satellite.

The additional Doppler shift due to the satellite moving can be described as: where is the relative speed of the satellite.

Audio

The Leslie speaker, most commonly associated with and predominantly used with the famous Hammond organ, takes advantage of the Doppler effect by using an electric motor to rotate an acoustic horn around a loudspeaker, sending its sound in a circle. This results at the listener's ear in rapidly fluctuating frequencies of a keyboard note.

Vibration measurement

A laser Doppler vibrometer (LDV) is a non-contact instrument for measuring vibration. The laser beam from the LDV is directed at the surface of interest, and the vibration amplitude and frequency are extracted from the Doppler shift of the laser beam frequency due to the motion of the surface.

Robotics

Dynamic real-time path planning in robotics to aid the movement of robots in a sophisticated environment with moving obstacles often take help of Doppler effect. Such applications are specially used for competitive robotics where the environment is constantly changing, such as robosoccer.

Inverse Doppler effect

Since 1968 scientists such as Victor Veselago have speculated about the possibility of an inverse Doppler effect. The size of the Doppler shift depends on the refractive index of the medium a wave is traveling through. Some materials are capable of negative refraction, which should lead to a Doppler shift that works in a direction opposite that of a conventional Doppler shift. The first experiment that detected this effect was conducted by Nigel Seddon and Trevor Bearpark in Bristol, United Kingdom in 2003. Later, the inverse Doppler effect was observed in some inhomogeneous materials, and predicted inside a Vavilov–Cherenkov cone.

See also

- Bistatic Doppler shift

- Differential Doppler effect

- Doppler cooling

- Dopplergraph

- Fading

- Fizeau experiment

- Photoacoustic Doppler effect

- Range rate

- Rayleigh fading

- Redshift

- Laser Doppler imaging

- Relativistic Doppler effect

Primary sources

- Buys Ballot (1845). "Akustische Versuche auf der Niederländischen Eisenbahn, nebst gelegentlichen Bemerkungen zur Theorie des Hrn. Prof. Doppler (in German)". Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 142 (11): 321–351. Bibcode:1845AnP...142..321B. doi:10.1002/andp.18451421102.

- Fizeau: "Acoustique et optique". Lecture, Société Philomathique de Paris, 29 December 1848. According to Becker(pg. 109), this was never published, but recounted by M. Moigno(1850): "Répertoire d'optique moderne" (in French), vol 3. pp 1165–1203 and later in full by Fizeau, "Des effets du mouvement sur le ton des vibrations sonores et sur la longeur d'onde des rayons de lumière"; . Annales de Chimie et de Physique, 19, 211–221.

- Scott Russell, John (1848). "On certain effects produced on sound by the rapid motion of the observer". Report of the Eighteenth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. 18 (7): 37–38. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Petrescu, Florian Ion T (2015). "Improving Medical Imaging and Blood Flow Measurement by using a New Doppler Effect Relationship". American Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences. 8 (4): 582–588. doi:10.3844/ajeassp.2015.582.588 – via ProQuest.

- Kozyrev, Alexander B.; van der Weide, Daniel W. (2005). "Explanation of the Inverse Doppler Effect Observed in Nonlinear Transmission Lines". Physical Review Letters. 94 (20): 203902. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..94t3902K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.203902. PMID 16090248.

References

- United States. Navy Department (1969). Principles and Applications of Underwater Sound, Originally Issued as Summary Technical Report of Division 6, NDRC, Vol. 7, 1946, Reprinted...1968. p. 194. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- Joseph, A. (2013). Measuring Ocean Currents: Tools, Technologies, and Data. Elsevier Science. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-12-391428-6. Retrieved 2021-03-30.

- ^ Giordano, Nicholas (2009). College Physics: Reasoning and Relationships. Cengage Learning. pp. 421–424. ISBN 978-0534424718.

- ^ Possel, Markus (2017). "Waves, motion and frequency: the Doppler effect". Einstein Online, Vol. 5. Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics, Potsdam, Germany. Archived from the original on September 14, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- Henderson, Tom (2017). "The Doppler Effect – Lesson 3, Waves". Physics tutorial. The Physics Classroom. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- Alec Eden The search for Christian Doppler, Springer-Verlag, Wien 1992. Contains a facsimile edition with an English translation.

- Becker (2011). Barbara J. Becker, Unravelling Starlight: William and Margaret Huggins and the Rise of the New Astronomy, illustrated Edition, Cambridge University Press, 2011; ISBN 110700229X, 9781107002296.

- ^ Walker, Jearl; Resnick, Robert; Halliday, David (2007). Halliday & Resnick Fundamentals of Physics (8th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 9781118233764. OCLC 436030602.

- Strutt (Lord Rayleigh), John William (1896). MacMillan & Co (ed.). The Theory of Sound. Vol. 2 (2 ed.). Macmillan. p. 154.

- "Doppler Shift". astro.ucla.edu.

- JA Peacock (2008). "A diatribe on expanding space". arXiv:0809.4573 .

- Bunn, E. F.; Hogg, D. W. (2009). "The kinematic origin of the cosmological redshift". American Journal of Physics. 77 (8): 688–694. arXiv:0808.1081. Bibcode:2009AmJPh..77..688B. doi:10.1119/1.3129103. S2CID 1365918.

- Harrison, Edward Robert (2000). Cosmology: The Science of the Universe (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 306ff. ISBN 978-0-521-66148-5.

- An excellent review of the topic in technical detail is given here: Percival, Will; Samushia, Lado; Ross, Ashley; Shapiro, Charles; Raccanelli, Alvise (2011). "Review article: Redshift-space distortions". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 369 (1957): 5058–67. Bibcode:2011RSPTA.369.5058P. doi:10.1098/rsta.2011.0370. PMID 22084293.

- Wolff, Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Christian. "Radar Basics". radartutorial.eu. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Davies, MJ; Newton, JD (2 July 2017). "Non-invasive imaging in cardiology for the generalist". British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 78 (7): 392–398. doi:10.12968/hmed.2017.78.7.392. PMID 28692375.

- Appis, AW; Tracy, MJ; Feinstein, SB (1 June 2015). "Update on the safety and efficacy of commercial ultrasound contrast agents in cardiac applications". Echo Research and Practice. 2 (2): R55–62. doi:10.1530/ERP-15-0018. PMC 4676450. PMID 26693339.

- Evans, D. H.; McDicken, W. N. (2000). Doppler Ultrasound (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-97001-9.

- Otilia Popescuy, Jason S. Harrisz and Dimitrie C. Popescuz, Designing the Communica- tion Sub-System for Nanosatellite CubeSat Missions: Operational and Implementation Perspectives, 2016, IEEE

- Qingchong, Liu (1999). "Doppler measurement and compensation in mobile satellite communications systems". MILCOM 1999. IEEE Military Communications. Conference Proceedings (Cat. No.99CH36341). Vol. 1. pp. 316–320. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.674.3987. doi:10.1109/milcom.1999.822695. ISBN 978-0-7803-5538-5. S2CID 12586746.

- Oberg, James (October 4, 2004). "Titan Calling". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. (offline as of 2006-10-14, see Internet Archive version)

- Arndt, D. (2015). On Channel Modelling for Land Mobile Satellite Reception (Doctoral dissertation).

- Agarwal, Saurabh; Gaurav, Ashish Kumar; Nirala, Mehul Kumar; Sinha, Sayan (2018). "Potential and Sampling Based RRT Star for Real-Time Dynamic Motion Planning Accounting for Momentum in Cost Function". Neural Information Processing. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 11307. pp. 209–221. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04239-4_19. ISBN 978-3-030-04238-7.

- "Doppler shift is seen in reverse". Physics World. 10 March 2011.

- Shi, Xihang; Lin, Xiao; Kaminer, Ido; Gao, Fei; Yang, Zhaoju; Joannopoulos, John D.; Soljačić, Marin; Zhang, Baile (October 2018). "Superlight inverse Doppler effect". Nature Physics. 14 (10): 1001–1005. arXiv:1805.12427. Bibcode:2018NatPh..14.1001S. doi:10.1038/s41567-018-0209-6. ISSN 1745-2473. S2CID 125790662.

Further reading

- Doppler, C. (1842). Über das farbige Licht der Doppelsterne und einiger anderer Gestirne des Himmels (About the coloured light of the binary stars and some other stars of the heavens). Publisher: Abhandlungen der Königl. Böhm. Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften (V. Folge, Bd. 2, S. 465–482) ; Prague: 1842 (Reissued 1903). Some sources mention 1843 as year of publication because in that year the article was published in the Proceedings of the Bohemian Society of Sciences. Doppler himself referred to the publication as "Prag 1842 bei Borrosch und André", because in 1842 he had a preliminary edition printed that he distributed independently.

- "Doppler and the Doppler effect", E. N. da C. Andrade, Endeavour Vol. XVIII No. 69, January 1959 (published by ICI London). Historical account of Doppler's original paper and subsequent developments.

- David Nolte (2020). The fall and rise of the Doppler effect. Physics Today, v. 73, pp. 31–35. DOI: 10.1063/PT.3.4429

- Adrian, Eleni (24 June 1995). "Doppler Effect". NCSA. Archived from the original on 12 May 2009. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

External links

- [REDACTED] Media related to Doppler effect at Wikimedia Commons

- The Doppler effect – The Feynman Lectures on Physics

- Doppler Effect, ScienceWorld

and emitted frequency

and emitted frequency  is given by:

is given by:

where

where

is the propagation speed of waves in the medium;

is the propagation speed of waves in the medium; is the speed of the receiver relative to the medium. In the formula,

is the speed of the receiver relative to the medium. In the formula,  is the speed of the source relative to the medium.

is the speed of the source relative to the medium.  where

where

is the wave's speed relative to the receiver;

is the wave's speed relative to the receiver; is the wave's speed relative to the source;

is the wave's speed relative to the source; is the wavelength.

is the wavelength. are small compared to the speed of the wave, the relationship between observed frequency

are small compared to the speed of the wave, the relationship between observed frequency

is the opposite of the relative speed of the receiver with respect to the source: it is positive when the source and the receiver are moving towards each other.

is the opposite of the relative speed of the receiver with respect to the source: it is positive when the source and the receiver are moving towards each other.

we can substitute using the

we can substitute using the  truncating all

truncating all  and higher terms:

and higher terms:

becomes insignificant, hence:

becomes insignificant, hence:

where

where  is the angle between the object's forward velocity and the line of sight from the object to the observer.

is the angle between the object's forward velocity and the line of sight from the object to the observer.

is twice that from the same target emitting a wave:

is twice that from the same target emitting a wave:

= 750 km). Fixed ground station.

= 750 km). Fixed ground station. is the velocity of the mobile station,

is the velocity of the mobile station,  is the velocity of the satellite,

is the velocity of the satellite,  is the relative velocity of the satellite,

is the relative velocity of the satellite,  is the elevation angle of the satellite and

is the elevation angle of the satellite and  is the carrier frequency,

is the carrier frequency,  is the maximum Doppler shift due to the mobile station moving (see

is the maximum Doppler shift due to the mobile station moving (see  is the additional Doppler shift due to the satellite moving.

is the additional Doppler shift due to the satellite moving. where

where  is the speed of the mobile station,

is the speed of the mobile station,  is the wavelength of the carrier,

is the wavelength of the carrier,  where

where  is the relative speed of the satellite.

is the relative speed of the satellite.