| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

The effects of a nuclear explosion on its immediate vicinity are typically much more destructive and multifaceted than those caused by conventional explosives. In most cases, the energy released from a nuclear weapon detonated within the lower atmosphere can be approximately divided into four basic categories:

- the blast and shock wave: 50% of total energy

- thermal radiation: 35% of total energy

- ionizing radiation: 5% of total energy (more in a neutron bomb)

- residual radiation: 5–10% of total energy with the mass of the explosion.

Depending on the design of the weapon and the location in which it is detonated, the energy distributed to any one of these categories may be significantly higher or lower. The physical blast effect is created by the coupling of immense amounts of energy, spanning the electromagnetic spectrum, with the surroundings. The environment of the explosion (e.g. submarine, ground burst, air burst, or exo-atmospheric) determines how much energy is distributed to the blast and how much to radiation. In general, surrounding a bomb with denser media, such as water, absorbs more energy and creates more powerful shock waves while at the same time limiting the area of its effect. When a nuclear weapon is surrounded only by air, lethal blast and thermal effects proportionally scale much more rapidly than lethal radiation effects as explosive yield increases. This bubble is faster than the speed of sound. The physical damage mechanisms of a nuclear weapon (blast and thermal radiation) are identical to those of conventional explosives, but the energy produced by a nuclear explosion is usually millions of times more powerful per unit mass, and temperatures may briefly reach the tens of millions of degrees.

Energy from a nuclear explosion is initially released in several forms of penetrating radiation. When there is surrounding material such as air, rock, or water, this radiation interacts with and rapidly heats the material to an equilibrium temperature (i.e. so that the matter is at the same temperature as the fuel powering the explosion). This causes vaporization of the surrounding material, resulting in its rapid expansion. Kinetic energy created by this expansion contributes to the formation of a shock wave which expands spherically from the center. Intense thermal radiation at the hypocenter forms a nuclear fireball which, if the explosion is low enough in altitude, is often associated with a mushroom cloud. In a high-altitude burst where the density of the atmosphere is low, more energy is released as ionizing gamma radiation and X-rays than as an atmosphere-displacing shockwave.

Direct effects

Blast damage

The high temperatures and radiation cause gas to move outward radially in a thin, dense shell called "the hydrodynamic front". The front acts like a piston that pushes against and compresses the surrounding medium to make a spherically expanding shock wave. At first, this shock wave is inside the surface of the developing fireball, which is created in a volume of air heated by the explosion's "soft" X-rays. Within a fraction of a second, the dense shock front obscures the fireball and continues to move past it, expanding outwards and free from the fireball, causing a reduction of light emanating from a nuclear detonation. Eventually the shock wave dissipates to the point where the light becomes visible again giving rise to the characteristic double flash caused by the shock wave–fireball interaction. It is this unique feature of nuclear explosions that is exploited when verifying that an atmospheric nuclear explosion has occurred and not simply a large conventional explosion, with radiometer instruments known as Bhangmeters capable of determining the nature of explosions.

For air bursts at or near sea level, 50–60% of the explosion's energy goes into the blast wave, depending on the size and the yield of the bomb. As a general rule, the blast fraction is higher for low yield weapons. Furthermore, it decreases at high altitudes because there is less air mass to absorb radiation energy and convert it into a blast. This effect is most important for altitudes above 30 km, corresponding to less than 1 percent of sea-level air density.

The effects of a moderate rain storm during an Operation Castle nuclear explosion were found to dampen, or reduce, peak pressure levels by approximately 15% at all ranges.

Much of the destruction caused by a nuclear explosion is from blast effects. Most buildings, except reinforced or blast-resistant structures, will suffer moderate damage when subjected to overpressures of only 35.5 kilopascals (kPa) (5.15 pounds-force per square inch or 0.35 atm). Data obtained from Japanese surveys following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki found that 8 psi (55 kPa) was sufficient to destroy all wooden and brick residential structures. This can reasonably be defined as the pressure capable of producing severe damage.

The blast wind at sea level may exceed 1,000 km/h, or ~300 m/s, approaching the speed of sound in air. The range for blast effects increases with the explosive yield of the weapon and also depends on the burst altitude. Contrary to what might be expected from geometry, the blast range is not maximal for surface or low altitude blasts but increases with altitude up to an "optimum burst altitude" and then decreases rapidly for higher altitudes. This is caused by the nonlinear behavior of shock waves. When the blast wave from an air burst reaches the ground it is reflected. Below a certain reflection angle, the reflected wave and the direct wave merge and form a reinforced horizontal wave, known as the '"Mach stem" and is a form of constructive interference. This phenomenon is responsible for the bumps or 'knees' in the above overpressure range graph.

For each goal overpressure, there is a certain optimum burst height at which the blast range is maximized over ground targets. In a typical air burst, where the blast range is maximized to produce the greatest range of severe damage, i.e. the greatest range that ~10 psi (69 kPa) of pressure is extended over, is a GR/ground range of 0.4 km for 1 kiloton (kt) of TNT yield; 1.9 km for 100 kt; and 8.6 km for 10 megatons (Mt) of TNT. The optimum height of burst to maximize this desired severe ground range destruction for a 1 kt bomb is 0.22 km; for 100 kt, 1 km; and for 10 Mt, 4.7 km.

Two distinct, simultaneous phenomena are associated with the blast wave in the air:

- Static overpressure, i.e., the sharp increase in pressure exerted by the shock wave. The overpressure at any given point is directly proportional to the density of the air in the wave.

- Dynamic pressures, i.e., drag exerted by the blast winds required to form the blast wave. These winds push, tumble and tear objects.

Most of the material damage caused by a nuclear air burst is caused by a combination of the high static overpressures and the blast winds. The long compression of the blast wave weakens structures, which are then torn apart by the blast winds. The compression, vacuum and drag phases together may last several seconds or longer, and exert forces many times greater than the strongest hurricane.

Acting on the human body, the shock waves cause pressure waves through the tissues. These waves mostly damage junctions between tissues of different densities (bone and muscle) or the interface between tissue and air. Lungs and the abdominal cavity, which contain air, are particularly injured. The damage causes severe hemorrhaging or air embolisms, either of which can be rapidly fatal. The overpressure estimated to damage lungs is about 70 kPa. Some eardrums would probably rupture around 22 kPa (0.2 atm) and half would rupture between 90 and 130 kPa (0.9 to 1.2 atm).

Thermal radiation

Nuclear weapons emit large amounts of thermal radiation as visible, infrared, and ultraviolet light, to which the atmosphere is largely transparent. This is known as "flash". The chief hazards are burns and eye injuries. On clear days, these injuries can occur well beyond blast ranges, depending on weapon yield. Fires may also be started by the initial thermal radiation, but the following high winds due to the blast wave may put out almost all such fires, unless the yield is very high where the range of thermal effects vastly outranges blast effects, as observed from explosions in the multi-megaton range. This is because the intensity of the blast effects drops off with the third power of distance from the explosion, while the intensity of radiation effects drops off with the second power of distance. This results in the range of thermal effects increasing markedly more than blast range as higher and higher device yields are detonated.

Thermal radiation accounts for between 35 and 45% of the energy released in the explosion, depending on the yield of the device. In urban areas, the extinguishing of fires ignited by thermal radiation may matter little, as in a surprise attack fires may also be started by blast-effect-induced electrical shorts, gas pilot lights, overturned stoves, and other ignition sources, as was the case in the breakfast-time bombing of Hiroshima. Whether or not these secondary fires will in turn be snuffed out as modern noncombustible brick and concrete buildings collapse in on themselves from the same blast wave is uncertain, not least of which, because of the masking effect of modern city landscapes on thermal and blast transmission are continually examined. When combustible frame buildings were blown down in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they did not burn as rapidly as they would have done had they remained standing. The noncombustible debris produced by the blast frequently covered and prevented the burning of combustible material.

Fire experts suggest that unlike Hiroshima, due to the nature of modern U.S. city design and construction, a firestorm in modern times is unlikely after a nuclear detonation. This does not exclude fires from being started but means that these fires will not form into a firestorm, due largely to the differences between modern building materials and those used in World War II-era Hiroshima.

There are two types of eye injuries from thermal radiation: flash blindness and retinal burn. Flash blindness is caused by the initial brilliant flash of light produced by the nuclear detonation. More light energy is received on the retina than can be tolerated but less than is required for irreversible injury. The retina is particularly susceptible to visible and short wavelength infrared light since this part of the electromagnetic spectrum is focused by the lens on the retina. The result is bleaching of the visual pigments and temporary blindness for up to 40 minutes. A retinal burn resulting in permanent damage from scarring is also caused by the concentration of direct thermal energy on the retina by the lens. It will occur only when the fireball is actually in the individual's field of vision and would be a relatively uncommon injury. Retinal burns may be sustained at considerable distances from the explosion. The height of burst and apparent size of the fireball, a function of yield and range will determine the degree and extent of retinal scarring. A scar in the central visual field would be more debilitating. Generally, a limited visual field defect, which will be barely noticeable, is all that is likely to occur.

When thermal radiation strikes an object, part will be reflected, part transmitted, and the rest absorbed. The fraction that is absorbed depends on the nature and color of the material. A thin material may transmit most of the radiation. A light-colored object may reflect much of the incident radiation and thus escape damage, like anti-flash white paint. The absorbed thermal radiation raises the temperature of the surface and results in scorching, charring, and burning of wood, paper, fabrics, etc. If the material is a poor thermal conductor, the heat is confined to the surface of the material.

The actual ignition of materials depends on how long the thermal pulse lasts and the thickness and moisture content of the target. Near ground zero where the energy flux exceeds 125 J/cm, what can burn, will. Farther away, only the most easily ignited materials will flame. Incendiary effects are compounded by secondary fires started by the blast wave effects such as from upset stoves and furnaces.

In Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, a tremendous firestorm developed within 20 minutes after detonation and destroyed many more buildings and homes, built out of predominantly 'flimsy' wooden materials. A firestorm has gale-force winds blowing in towards the center of the fire from all directions. It is not peculiar to nuclear explosions, having been observed frequently in large forest fires and following incendiary raids during World War II. Despite fires destroying a large area of Nagasaki, no true firestorm occurred in the city even though a higher yielding weapon was used. Many factors explain this seeming contradiction, including a different time of bombing than Hiroshima, terrain, and crucially, a lower fuel loading/fuel density than that of Hiroshima.

Nagasaki probably did not furnish sufficient fuel for the development of a firestorm as compared to the many buildings on the flat terrain at Hiroshima.

2 and N

2) naturally found in air. These two atmospheric gases, though generally unreactive toward each other, form NOx species when heated to excess, specifically nitrogen dioxide, which is largely responsible for the color. There was concern in the 1970s and 1980s, later proven unfounded, regarding fireball NOx and ozone loss.

As thermal radiation travels more or less in a straight line from the fireball (unless scattered), any opaque object will produce a protective shadow that provides protection from the flash burn. Depending on the properties of the underlying surface material, the exposed area outside the protective shadow will be either burnt to a darker color, such as charring wood, or a brighter color, such as asphalt. If such a weather phenomenon as fog or haze is present at the point of the nuclear explosion, it scatters the flash, with radiant energy then reaching burn-sensitive substances from all directions. Under these conditions, opaque objects are therefore less effective than they would otherwise be without scattering, as they demonstrate maximum shadowing effect in an environment of perfect visibility and therefore zero scatterings. Similar to a foggy or overcast day, although there are few if any, shadows produced by the sun on such a day, the solar energy that reaches the ground from the sun's infrared rays is nevertheless considerably diminished, due to it being absorbed by the water of the clouds and the energy also being scattered back into space. Analogously, so too is the intensity at a range of burning flash energy attenuated, in units of J/cm, along with the slant/horizontal range of a nuclear explosion, during fog or haze conditions. So despite any object that casts a shadow being rendered ineffective as a shield from the flash by fog or haze, due to scattering, the fog fills the same protective role, but generally only at the ranges that survival in the open is just a matter of being protected from the explosion's flash energy.

The thermal pulse also is responsible for warming the atmospheric nitrogen close to the bomb and causing the creation of atmospheric NOx smog components. This, as part of the mushroom cloud, is shot into the stratosphere where it is responsible for dissociating ozone there, in the same way combustion NOx compounds do. The amount created depends on the yield of the explosion and the blast's environment. Studies done on the total effect of nuclear blasts on the ozone layer have been at least tentatively exonerating after initial discouraging findings.

Indirect effects

Electromagnetic pulse

Gamma rays from a nuclear explosion produce high energy electrons through Compton scattering. For high altitude nuclear explosions, these electrons are captured in the Earth's magnetic field at altitudes between 20 and 40 kilometers where they interact with the Earth's magnetic field to produce a coherent nuclear electromagnetic pulse (NEMP) which lasts about one millisecond. Secondary effects may last for more than a second. The pulse is powerful enough to cause moderately long metal objects (such as cables) to act as antennas and generate high voltages due to interactions with the electromagnetic pulse. These voltages can destroy unshielded electronics. There are no known biological effects of EMP. The ionized air also disrupts radio traffic that would normally bounce off the ionosphere.

Electronics can be shielded by wrapping them completely in conductive material such as metal foil; the effectiveness of the shielding may be less than perfect. Proper shielding is a complex subject due to the large number of variables involved. Semiconductors, especially integrated circuits, are extremely susceptible to the effects of EMP due to the close proximity of their p–n junctions, but this is not the case with thermionic tubes (or valves) which are relatively immune to EMP. A Faraday cage does not offer protection from the effects of EMP unless the mesh is designed to have holes no bigger than the smallest wavelength emitted from a nuclear explosion.

Large nuclear weapons detonated at high altitudes also cause geomagnetically induced current in very long electrical conductors. The mechanism by which these geomagnetically induced currents are generated is entirely different from the gamma-ray induced pulse produced by Compton electrons.

Radar blackout

See also: Nuclear blackout and Christofilos effectThe heat of the explosion causes air in the vicinity to become ionized, creating the fireball. The free electrons in the fireball affect radio waves, especially at lower frequencies. This causes a large area of the sky to become opaque to radar, especially those operating in the VHF and UHF frequencies, which is common for long-range early warning radars. The effect is less for higher frequencies in the microwave region, as well as lasting a shorter time – the effect falls off both in strength and the affected frequencies as the fireball cools and the electrons begin to re-form onto free nuclei.

A second blackout effect is caused by the emission of beta particles from the fission products. These can travel long distances, following the Earth's magnetic field lines. When they reach the upper atmosphere they cause ionization similar to the fireball but over a wider area. Calculations demonstrate that one megaton of fission, typical of a two-megaton H-bomb, will create enough beta radiation to blackout an area 400 kilometres (250 miles) across for five minutes. Careful selection of the burst altitudes and locations can produce an extremely effective radar-blanking effect. The physical effects giving rise to blackouts also cause EMP, which can also cause power blackouts. The two effects are otherwise unrelated, and the similar naming can be confusing.

Ionizing radiation

About 5% of the energy released in a nuclear air burst is in the form of ionizing radiation: neutrons, gamma rays, alpha particles and electrons moving at speeds up to the speed of light. Gamma rays are high-energy electromagnetic radiation; the others are particles that move slower than light. The neutrons result almost exclusively from the fission and fusion reactions, while the initial gamma radiation includes that arising from these reactions as well as that resulting from the decay of short-lived fission products. The intensity of initial nuclear radiation decreases rapidly with distance from the point of burst because the radiation spreads over a larger area as it travels away from the explosion (the inverse-square law). It is also reduced by atmospheric absorption and scattering.

The character of the radiation received at a given location also varies with the distance from the explosion. Near the point of the explosion, the neutron intensity is greater than the gamma intensity, but with increasing distance the neutron-gamma ratio decreases. Ultimately, the neutron component of the initial radiation becomes negligible in comparison with the gamma component. The range for significant levels of initial radiation does not increase markedly with weapon yield and, as a result, the initial radiation becomes less of a hazard with increasing yield. With larger weapons, above 50 kt (200 TJ), blast and thermal effects are so much greater in importance that prompt radiation effects can be ignored.

The neutron radiation serves to transmute the surrounding matter, often rendering it radioactive. When added to the dust of radioactive material released by the bomb, a large amount of radioactive material is released into the environment. This form of radioactive contamination is known as nuclear fallout and poses the primary risk of exposure to ionizing radiation for a large nuclear weapon.

Details of nuclear weapon design also affect neutron emission: the gun-type assembly Little Boy leaked far more neutrons than the implosion-type 21 kt Fat Man because the light hydrogen nuclei (protons) predominating in the exploded TNT molecules (surrounding the core of Fat Man) slowed down neutrons very efficiently while the heavier iron atoms in the steel nose forging of Little Boy scattered neutrons without absorbing much neutron energy.

It was found in early experimentation that normally most of the neutrons released in the cascading chain reaction of the fission bomb are absorbed by the bomb case. Building a bomb case of materials which transmitted rather than absorbed the neutrons could make the bomb more intensely lethal to humans from prompt neutron radiation. This is one of the features used in the development of the neutron bomb.

Earthquake

The seismic pressure waves created from an explosion may release energy within nearby plates or otherwise cause an earthquake event. An underground explosion concentrates this pressure wave, and a localized earthquake event is more probable. The first and fastest wave, equivalent to a normal earthquake's P wave, can inform the location of the test; the S wave and the Rayleigh wave follow. These can all be measured in most circumstances by seismic stations across the globe, and comparisons with actual earthquakes can be used to help determine estimated yield via differential analysis, by the modelling of the high-frequency (>4 Hz) teleseismic P wave amplitudes. However, theory does not suggest that a nuclear explosion of current yields could trigger fault rupture and cause a major quake at distances beyond a few tens of kilometers from the shot point.

Summary of the effects

The following table summarizes the most important effects of single nuclear explosions under ideal, clear skies, weather conditions. Tables like these are calculated from nuclear weapons effects scaling laws. Advanced computer modelling of real-world conditions and how they impact on the damage to modern urban areas has found that most scaling laws are too simplistic and tend to overestimate nuclear explosion effects. The scaling laws that were used to produce the table below assume (among other things) a perfectly level target area, no attenuating effects from urban terrain masking (e.g. skyscraper shadowing), and no enhancement effects from reflections and tunneling by city streets. As a point of comparison in the chart below, the most likely nuclear weapons to be used against countervalue city targets in a global nuclear war are in the sub-megaton range. Weapons of yields from 100 to 475 kilotons have become the most numerous in the US and Russian nuclear arsenals; for example, the warheads equipping the Russian Bulava submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) have a yield of 150 kilotons. US examples are the W76 and W88 warheads, with the lower yield W76 being over twice as numerous as the W88 in the US nuclear arsenal.

| Effects | Explosive yield / height of burst | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 kt / 200 m | 20 kt / 540 m | 1 Mt / 2.0 km | 20 Mt / 5.4 km | ||

| Blast—effective ground range GR / km | |||||

| Urban areas completely levelled (20 psi or 140 kPa) | 0.2 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 6.4 | |

| Destruction of most civilian buildings (5 psi or 34 kPa) | 0.6 | 1.7 | 6.2 | 17 | |

| Moderate damage to civilian buildings (1 psi or 6.9 kPa) | 1.7 | 4.7 | 17 | 47 | |

| Railway cars thrown from tracks and crushed (62 kPa; values for other than 20 kt are extrapolated using the cube-root scaling) |

≈0.4 | 1.0 | ≈4 | ≈10 | |

| Thermal radiation—effective ground range GR / km | |||||

| Fourth degree burns, Conflagration | 0.5 | 2.0 | 10 | 30 | |

| Third degree burns | 0.6 | 2.5 | 12 | 38 | |

| Second degree burns | 0.8 | 3.2 | 15 | 44 | |

| First degree burns | 1.1 | 4.2 | 19 | 53 | |

| Effects of instant nuclear radiation—effective slant range SR / km | |||||

| Lethal total dose (neutrons and gamma rays) | 0.8 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 4.7 | |

| Total dose for acute radiation syndrome | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 5.4 | |

For the direct radiation effects the slant range instead of the ground range is shown here because some effects are not given even at ground zero for some burst heights. If the effect occurs at ground zero the ground range can be derived from slant range and burst altitude (Pythagorean theorem).

"Acute radiation syndrome" corresponds here to a total dose of one gray, "lethal" to ten grays. This is only a rough estimate since biological conditions are neglected here.

Further complicating matters, under global nuclear war scenarios with conditions similar to that during the Cold War, major strategically important cities like Moscow and Washington are likely to be hit numerous times from sub-megaton multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles, in a cluster bomb or "cookie-cutter" configuration. It has been reported that during the height of the Cold War in the 1970s Moscow was targeted by up to 60 warheads.

The reason that the cluster bomb concept is preferable in the targeting of cities is twofold: the first is that large singular warheads are much easier to neutralize as both tracking and successful interception by anti-ballistic missile systems than it is when several smaller incoming warheads are approaching. This strength in numbers advantage to lower yield warheads is further compounded by such warheads tending to move at higher incoming speeds, due to their smaller, more slender physics package size, assuming both nuclear weapon designs are the same (a design exception being the advanced W88). The second reason for this cluster bomb, or 'layering' (using repeated hits by accurate low yield weapons) is that this tactic along with limiting the risk of failure reduces individual bomb yields, and therefore reduces the possibility of any serious collateral damage to non-targeted nearby civilian areas, including that of neighboring countries. This concept was pioneered by Philip J. Dolan and others.

Other phenomena

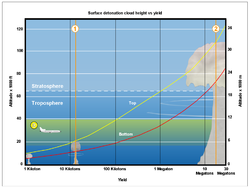

0 = Approx. altitude at which a commercial aircraft operates

1 = Fat Man

2 = Castle Bravo

Gamma rays from the nuclear processes preceding the true explosion may be partially responsible for the following fireball, as they may superheat nearby air and/or other material. The vast majority of the energy that goes on to form the fireball is in the soft X-ray region of the electromagnetic spectrum, with these X-rays being produced by the inelastic collisions of the high-speed fission and fusion products. It is these reaction products and not the gamma rays which contain most of the energy of the nuclear reactions in the form of kinetic energy. This kinetic energy of the fission and fusion fragments is converted into internal and then radiation energy by approximately following the process of blackbody radiation emitting in the soft X-ray region.

As a result of numerous inelastic collisions, part of the kinetic energy of the fission fragments is converted into internal and radiation energy. Some of the electrons are removed entirely from the atoms, thus causing ionization. Others are raised to higher energy (or excited) states while still remaining attached to the nuclei. Within an extremely short time, perhaps a hundredth of a microsecond or so, the weapon residues consist essentially of completely and partially stripped (ionized) atoms, many of the latter being in excited states, together with the corresponding free electrons. The system then immediately emits electromagnetic (thermal) radiation, the nature of which is determined by the temperature. Since this is of the order of 10 degrees, most of the energy emitted within a microsecond or so is in the soft X-ray region. Because temperature depends on the average internal energy/heat of the particles in a certain volume, internal energy or heat is from kinetic energy.

For an explosion in the atmosphere, the fireball quickly expands to maximum size and then begins to cool as it rises like a balloon through buoyancy in the surrounding air. As it does so, it takes on the flow pattern of a vortex ring with incandescent material in the vortex core as seen in certain photographs. This effect is known as a mushroom cloud. Sand will fuse into glass if it is close enough to the nuclear fireball to be drawn into it, and is thus heated to the necessary temperatures to do so; this is known as trinitite. At the explosion of nuclear bombs lightning discharges sometimes occur.

Smoke trails are often seen in photographs of nuclear explosions. These are not from the explosion; they are left by sounding rockets launched just prior to detonation. These trails allow observation of the blast's normally invisible shock wave in the moments following the explosion.

The heat and airborne debris created by a nuclear explosion can cause rain; the debris is thought to do this by acting as cloud condensation nuclei. During the city firestorm which followed the Hiroshima explosion, drops of water were recorded to have been about the size of marbles. This was termed black rain and has served as the source of a book and film by the same name. Black rain is not unusual following large fires and is commonly produced by pyrocumulus clouds during large forest fires. The rain directly over Hiroshima on that day is said to have begun around 9 a.m. with it covering a wide area from the hypocenter to the northwest, raining heavily for one hour or more in some areas. The rain directly over the city may have carried neutron activated building material combustion products, but it did not carry any appreciable nuclear weapon debris or fallout, although this is generally to the contrary to what other less technical sources state. The "oily" black soot particles, are a characteristic of incomplete combustion in the city firestorm.

The element einsteinium was discovered when analyzing nuclear fallout.

A side-effect of the Pascal-B nuclear test during Operation Plumbbob may have resulted in the first man-made object launched on an Earth escape trajectory. The so-called "thunder well" effect from the underground explosion may have launched a metal cover plate into space at six times Earth's escape velocity, although the evidence remains subject to debate, due to aerodynamic heating likely disintegrating it before it could exit the atmosphere.

Ignition of fusion in the environment

Atmospheric ignition

In 1942, there was speculation among the scientists developing the first nuclear weapons in the Manhattan Project that a sufficiently large nuclear explosion might ignite fusion reactions the Earth's atmosphere. Since the proposal of the CNO cycle in 1937, it was known that not only the hydrogen in water vapor, but the carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen nuclei in the atmosphere undergo exothermic fusion reactions to heavier nuclei; at stellar temperatures they behave as a fuel. The fear was that similar temperatures in the bomb's initial fireball might trigger the exothermic reactions or , sustaining itself until all the world's atmospheric nitrogen was consumed. Hans Bethe was assigned to study this hypothesis from the project's earliest days, and he eventually concluded that such a reaction could not sustain itself on a large scale due to cooling of the nuclear fireball through an inverse Compton effect. Richard Hamming was asked to make a similar calculation just before the first nuclear test, and he reached the same conclusion. Nevertheless, the notion has persisted as a rumor for many years and was the source of apocalyptic gallows humor at the Trinity test where Enrico Fermi took side bets on atmospheric ignition.

Subsequent analysis shows that besides the cooling effect, the latter reaction, with a Gamow energy of 16.46 GeV, was unlikely to have occurred in even a single instance during the Trinity test, as the fireball core reached 1.01 × 10 K, equivalent to the far lower thermal energy of 8.7 MeV. However, the possibility of fusion of hydrogen nuclei during the test, whose Gamow energies are on the order of 1 MeV, is not known. The first artificial initiation of a thermonuclear reaction is accepted to be the 1951 American nuclear test Greenhouse George.

Oceanic ignition

Fears of igniting the ocean's higher density of hydrogen, deuterium, or oxygen nuclei during American testing in the Pacific, remained a serious concern, especially as yields increased by orders of magnitude. These were raised from the first air burst over water and submerged tests in Operation Crossroads at Bikini Atoll, and continuing with the first full thermonuclear and megaton-level test of Ivy Mike.

Survivability

Main articles: Duck and Cover (film), Protect and Survive, and Nuclear bombs and healthSurvivability is highly dependent on factors such as if one is indoors or out, the size of the explosion, the proximity to the explosion, and to a lesser degree the direction of the wind carrying fallout. Death is highly likely and radiation poisoning is almost certain if one is caught in the open with no terrain or building masking effects within a radius of 0–3 kilometres (0.0–1.9 mi) from a 1 megaton airburst, and the 50% chance of death from the blast extends out to ~8 kilometres (5.0 mi) from the same 1 megaton atmospheric explosion.

An example that highlights the variability in the real world and the effect of being indoors is Akiko Takakura. Despite the lethal radiation and blast zone extending well past her position at Hiroshima, Takakura survived the effects of a 16 kt atomic bomb at a distance of 300 metres (980 ft) from the hypocenter, with only minor injuries, due mainly to her position in the lobby of the Bank of Japan, a reinforced concrete building, at the time. In contrast, the unknown person sitting outside, fully exposed, on the steps of the Sumitomo Bank, next door to the Bank of Japan, received lethal third-degree burns and was then likely killed by the blast, in that order, within two seconds.

With medical attention, radiation exposure is survivable to 200 rems of acute dose exposure. If a group of people is exposed to a 50 to 59 rems acute (within 24 hours) radiation dose, none will get radiation sickness. If the group is exposed to 60 to 180 rems, 50% will become sick with radiation poisoning. If medically treated, all of the 60–180 rems group will survive. If the group is exposed to 200 to 450 rems, most if not all of the group will become sick; 50% will die within two to four weeks, even with medical attention. If the group is exposed to 460 to 600 rems, 100% of the group will get radiation poisoning, and 50% will die within one to three weeks. If the group is exposed to 600 to 1000 rems, 50% will die in one to three weeks. If the group is exposed to 1,000 to 5,000 rems, 100% of the group will die within 2 weeks. At 5,000 rems, 100% of the group will die within 2 days.

Nuclear explosion impact on humans indoors

Researchers from the University of Nicosia simulated, using high-order computational fluid dynamics, an atomic bomb explosion from a typical intercontinental ballistic missile and the resulting blast wave to see how it would affect people sheltering indoors. They found that the blast wave was enough in the moderate damage zone to topple some buildings and injure people caught outdoors. However, sturdier buildings, such as concrete structures, can remain standing. The team used advanced computer modelling to study how a nuclear blast wave speeds through a standing structure. Their simulated structure featured rooms, windows, doorways, and corridors and allowed them to calculate the speed of the air following the blast wave and determine the best and worst places to be.

The study showed that high airspeeds remain a considerable hazard and can still result in severe injuries or even fatalities. Furthermore, simply being in a sturdy building is not enough to avoid risk. The tight spaces can increase airspeed, and the involvement of the blast wave causes air to reflect off walls and bend around corners. In the worst cases, this can produce a force equivalent to multiple times a human's body weight. The most dangerous critical indoor locations to avoid are windows, corridors, and doors. The study received considerable interest from the international press.

See also

- Bomb pulse

- Effects of nuclear explosions on human health

- Lists of nuclear disasters and radioactive incidents

- List of nuclear weapons tests

- Nuclear warfare

- Nuclear holocaust

- Nuclear terrorism

- Peaceful nuclear explosion

- Rope trick effect

- Underwater explosion

- Visual depictions of nuclear explosions in fiction

References

- "Nuclear Explosions: Weapons, Improvised Nuclear Devices". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 16 February 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- "Nuclear Radiation Protection Guide Civil Defense". www.atomicarchive.com. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- ^ "Yield (kilotons)". Archived from the original on 2013-06-07. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- Glasstone, Samuel; Dolan, Philip J., eds. (1977). The Effects of Nuclear Weapons. U.S. Department of Defense. doi:10.2172/6852629. ISBN 978-0-318-20369-0. OSTI 6852629.

- "The Soviet Weapons Program – The Tsar Bomba". www.nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ AFSWP (30 March 2018). "Military Effects Studies on Operation CASTLE". Retrieved 30 March 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- "The Mach Stem – Effects of Nuclear Weapons". www.atomicarchive.com. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Striving for a Safer World Since 1945".

- http://www.atomicarchive.com/Movies/machstem.shtml video of the Mach 'Y' stem, it is not a phenomenon unique to nuclear explosions, conventional explosions also produce it.

- ^ "Nuclear Bomb Effects". The Atomic Archive. solcomhouse.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ Oughterson, A. W.; LeRoy, G. V.; Liebow, A. A.; Hammond, E. C.; Barnett, H. L.; Rosenbaum, J. D.; Schneider, B. A. (19 April 1951). "Medical Effects Of Atomic Bombs The Report Of The Joint Commission For The Investigation Of The Effects Of The Atomic Bomb In Japan Volume 1". osti.gov. doi:10.2172/4421057. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Modeling the Effects of Nuclear Weapons in an Urban Setting" (PDF). 6 July 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011.

- Glasstone & Dolan (1977) Thermal effects Chapter p. 26

- Planning Guidance for a Response to a Nuclear Detonation (PDF), Federal Emergency Management Agency, June 2010, Wikidata Q63152882, p. 24. Note: No citation is provided to support the claim that "a firestorm in modern times is unlikely".

- Glasstone & Dolan (1977) Thermal effects Chapter p. 304

- "Damage by the Heat Rays/Shadow Imprinted on an Electric Pole". www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp. Archived from the original on 12 September 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Various other effects of the radiated heat were noted, including the lightening of asphalt road surfaces in spots that had not been protected from the radiated heat by any object such as that of a person walking along the road. Various other surfaces were discolored in different ways by the radiated heat." From the Flash Burn Archived 24 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine section of "The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki" Archived 2014-02-24 at the Wayback Machine, a report by the Manhattan Engineering District, 29 June 1946,

- "Glasstone & Dolan 1977 Thermal effects Chapter" (PDF). fourmilab.ch. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Christie, J.D. (20 May 1976). "Atmospheric ozone depletion by nuclear weapons testing". Journal of Geophysical Research. 81 (15): 2583–2594. Bibcode:1976JGR....81.2583C. doi:10.1029/JC081i015p02583. This link is to the abstract; the whole paper is behind a paywall.

- ^ Garwin, Richard L.; Bethe, Hans A. (1968). "Anti-Ballistic-Missile Systems". Scientific American. 218 (3): 21–31. Bibcode:1968SciAm.218c..21G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0368-21. JSTOR 24925996.

- Pattison, J.E.; Hugtenburg, R.P.; Charles, M.W.; Beddoe, A.H. (2 May 2001). "Experimental Simulation of A-Bomb Gamma Ray Spectra for Radiobiology Studies". Radiation Protection Dosimetry. 95 (2): 125–135. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006532. PMID 11572640.

- "Credible effects of nuclear weapons for real-world peace: peace through tested, proved and practical declassified deterrence and countermeasures against collateral damage. Credible deterrence through simple, effective protection against concentrated and dispersed invasions and aerial attacks. Discussions of the facts as opposed to inaccurate, misleading lies of the "disarm or be annihilated" political dogma variety. Hiroshima and Nagasaki anti-nuclear propaganda debunked by the hard facts. Walls, not wars. Walls bring people together by stopping divisive terrorists". glasstone.blogspot.com. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ "How Security Experts Track North Korea's Nuclear Activity". Scientific American.

- Voytan, Dimitri P.; Lay, Thorne; Chaves, Esteban J.; Ohman, John T. (May 2019). "Yield Estimates for the Six North Korean Nuclear Tests from Teleseismic P Wave Modeling and Intercorrelation of P and Pn Recordings". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 124 (5): 4916–4939. Bibcode:2019JGRB..124.4916V. doi:10.1029/2019JB017418. S2CID 150176436.

- "Alsos: Nuclear Explosions and Earthquakes: The Parted Veil". alsos.wlu.edu. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Nuke 2". Archived from the original on 26 May 2006. Retrieved 22 March 2006.

- Paul P. Craig, John A. Jungerman. (1990) The Nuclear Arms Race: Technology and Society p. 258

- Calder, Nigel "The effects of a 100 Megaton bomb" New Scientist, 14 Sep 1961, p. 644

- Sartori, Leo "Effects of nuclear weapons" Physics and Nuclear Arms Today (Readings from Physics Today) p. 2

- "Effects of Nuclear Explosions". nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Modeling the Effects of Nuclear Weapons in an Urban Setting" (PDF). 6 July 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- The modern Russian Bulava SLBM is armed with warheads of 100–150 kilotons in yield. Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Effects of Nuclear War" Office of Technology Assessment, May 1979. pp. 42 and 44. Compare the destruction from a single 1 megaton weapon detonation on Leningrad on page 42 to that of 10 clustered 40 kiloton weapon detonations in a 'cookie-cutter' configuration on page 44; the level of total destruction is similar in both cases despite the total yield in the second attack scenario being less than half of that delivered in the 1 megaton case

- Sartori, Leo "Effects of nuclear weapons" Physics and Nuclear Arms Today (Readings from Physics Today) p. 22

- Robert C. Aldridge (1983) First Strike! The Pentagon's Strategy for Nuclear War p. 65

- "The Nuclear Matters Handbook". Archived from the original on 2 March 2013.

- "The Effects of Nuclear Weapons (1977) Chapter II: 'Descriptions of Nuclear Explosions, Scientific Aspects of Nuclear Explosion Phenomena'". vt.edu. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Photo". nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Robert Hermes and William Strickfaden, 2005, New Theory on the Formation of Trinitite, Nuclear Weapons Journal http://www.wsmr.army.mil/pao/TrinitySite/NewTrinititeTheory.htm Archived 26 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Colvin, J. D.; Mitchell, C. K.; Greig, J. R.; Murphy, D. P.; Pechacek, R. E.; Raleigh, M. (1987). "An empirical study of the nuclear explosion-induced lightning seen on IVY-MIKE". Journal of Geophysical Research. 92 (D5): 5696. Bibcode:1987JGR....92.5696C. doi:10.1029/JD092iD05p05696.

- "What are Those Smoke Trails Doing in That Test Picture?". nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Hersey, John (23 August 1946). "Hiroshima". The New Yorker.

- "Damage of Radiation". hiroshima-spirit.jp. 4 January 2025.

- Strom, P O; Miller, C F (1969). Interaction of Fallout with Fires. OSTI 4078266. DTIC AD0708558.

- Wiescher, Michael; Langanke, Karlheinz (2024-03-01). "Manhattan Project astrophysics" (PDF). Physics Today. 77 (3). AIP Publishing: 34–41. doi:10.1063/pt.jksg.hage. ISSN 0031-9228. Retrieved 2025-01-16.

- Konopinski, E. J; Marvin, C.; Teller, Edward (1946). Ignition of the Atmosphere with Nuclear Bombs (PDF) (Report). Vol. LA–602. Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 6 December 2013. The date of the article is 1946; it may have been written to demonstrate due diligence on the problem. It was declassified in 1970.

- Hamming, Richard (1998). "Mathematics on a Distant Planet". The American Mathematical Monthly. 105 (7): 640–650. doi:10.1080/00029890.1998.12004938. JSTOR 2589247.

- Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J. (2005). "Chapter 22". American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 306.

- Fotedar, Ayush; Boamah, Jeremy Owusu; McCrea, Alec (2024-11-08). "P4 2 Atmospheric Ignition". Physics Special Topics. 23 (1). Retrieved 2025-01-16.

- Rabinowitz, M.; Kim, Y. E.; Rice, R. A.; Chulick, G. S. (1991). Cluster-impact fusion: Bridge between hot and cold fusion?. Vol. 228. AIP. p. 846–866. doi:10.1063/1.40722.

- "Operation Greenhouse". The Nuclear Weapon Archive. 2003-08-02. Retrieved 2025-01-16.

- Wiescher, Michael; Langanke, Karlheinz (2024). "Nuclear astrophysicists at war". Natural Sciences. 4 (1): 13. doi:10.1002/ntls.20230023. ISSN 2698-6248. Retrieved 2025-01-16.

- Kosyakov, Boris (2023-05-16). "A farewell to particles". arXiv.org. Retrieved 2025-01-16.

- Johnston, Wm. Robert (n.d.). "Range of weapons effects". Johnston's Archive. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023.

- Johnston, Wm. Robert (n.d.). "Range of weapons effects". Johnston's Archive. Archived from the original on 10 October 2023.

- "What I Want to Say Now". www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Testimony of Akiko Takakura - The Voice of Hibakusha - The Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki - Historical Documents - atomicarchive.com". www.atomicarchive.com. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Damage by the Heat Rays". Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. n.d. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- McCarthy, Walton (2013). Principles of Protection: U. S. Handbook of NBC Weapon Fundamentals and Shelter Engineering Design Standards (6th ed.). Dallas, TX: Brown Books Publishing Group. p. 420. ISBN 978-1612541143. LCCN 2013946141. OCLC 862209369. OL 27480913M.

- ^ Kokkinakis, Ioannis W.; Drikakis, Dimitris (January 2023). "Nuclear explosion impact on humans indoors". Physics of Fluids. 35 (1): 016114. Bibcode:2023PhFl...35a6114K. doi:10.1063/5.0132565. eISSN 1089-7666. ISSN 1070-6631. S2CID 256124805.

External links

- Nuclear Weapon Testing Effects Archived 2020-05-29 at the Wayback Machine – Comprehensive video archive

- Underground Bomb Shelters Archived 2007-10-14 at the Wayback Machine

- The Federation of American Scientists provide solid information on weapons of mass destruction, including nuclear weapons and their effects

- The Nuclear War Survival Skills is a public domain text and is an excellent source on how to survive a nuclear attack.

- Ground Zero: A Javascript simulation of the effects of a nuclear explosion in a city

- Oklahoma Geological Survey Nuclear Explosion Catalog lists 2,199 explosions with their date, country, location, yield, etc.

- Australian Government database of all nuclear explosions

- Nuclear Weapon Archive from Carey Sublette (NWA) is a reliable source of information and has links to other sources.

- NWA repository of blast models mainly used for the effects table (especially DOS programs BLAST and WE)

- HYDESim: High-Yield Detonation Effects Simulator – Mashup of Google Maps and Javascript to calculate blast effects.

- NUKEMAP – Google Maps/Javascript effects mapper, which includes fireball size, blast pressure, ionizing radiation, and thermal radiation as well as qualitative descriptions.

- Nuclear Weapons Frequently Asked Questions

- Atomic Forum

- Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan, The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, Third Edition, United States Department of Defense & Energy Research and Development Administration Available Online

- Nuclear Emergency and Radiation Resources

- Outrider believes in the power of an informed, engaged public.

| Nuclear technology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

or

or  , sustaining itself until all the world's atmospheric nitrogen was consumed.

, sustaining itself until all the world's atmospheric nitrogen was consumed.