| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (November 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The margin of error is a statistic expressing the amount of random sampling error in the results of a survey. The larger the margin of error, the less confidence one should have that a poll result would reflect the result of a census of the entire population. The margin of error will be positive whenever a population is incompletely sampled and the outcome measure has positive variance, which is to say, whenever the measure varies.

The term margin of error is often used in non-survey contexts to indicate observational error in reporting measured quantities.

Concept

Consider a simple yes/no poll as a sample of respondents drawn from a population reporting the percentage of yes responses. We would like to know how close is to the true result of a survey of the entire population , without having to conduct one. If, hypothetically, we were to conduct a poll over subsequent samples of respondents (newly drawn from ), we would expect those subsequent results to be normally distributed about , the true but unknown percentage of the population. The margin of error describes the distance within which a specified percentage of these results is expected to vary from .

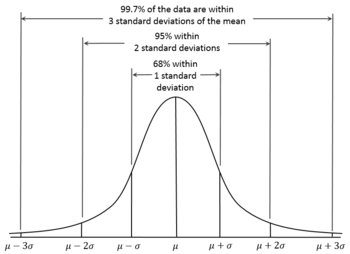

Going by the Central limit theorem, the margin of error helps to explain how the distribution of sample means (or percentage of yes, in this case) will approximate a normal distribution as sample size increases. If this applies, it would speak about the sampling being unbiased, but not about the inherent distribution of the data.

According to the 68-95-99.7 rule, we would expect that 95% of the results will fall within about two standard deviations () either side of the true mean . This interval is called the confidence interval, and the radius (half the interval) is called the margin of error, corresponding to a 95% confidence level.

Generally, at a confidence level , a sample sized of a population having expected standard deviation has a margin of error

where denotes the quantile (also, commonly, a z-score), and is the standard error.

Standard deviation and standard error

We would expect the average of normally distributed values to have a standard deviation which somehow varies with . The smaller , the wider the margin. This is called the standard error .

For the single result from our survey, we assume that , and that all subsequent results together would have a variance .

Note that corresponds to the variance of a Bernoulli distribution.

Maximum margin of error at different confidence levels

For a confidence level , there is a corresponding confidence interval about the mean , that is, the interval within which values of should fall with probability . Precise values of are given by the quantile function of the normal distribution (which the 68–95–99.7 rule approximates).

Note that is undefined for , that is, is undefined, as is .

| 0.84 | 0.994457883210 | 0.9995 | 3.290526731492 | |

| 0.95 | 1.644853626951 | 0.99995 | 3.890591886413 | |

| 0.975 | 1.959963984540 | 0.999995 | 4.417173413469 | |

| 0.99 | 2.326347874041 | 0.9999995 | 4.891638475699 | |

| 0.995 | 2.575829303549 | 0.99999995 | 5.326723886384 | |

| 0.9975 | 2.807033768344 | 0.999999995 | 5.730728868236 | |

| 0.9985 | 2.967737925342 | 0.9999999995 | 6.109410204869 |

The inset parabola illustrates the relationship between at and at . In the example, MOE95(0.71) ≈ 0.9 × ±3.1% ≈ ±2.8%.

Since at , we can arbitrarily set , calculate , , and to obtain the maximum margin of error for at a given confidence level and sample size , even before having actual results. With

Also, usefully, for any reported

Specific margins of error

If a poll has multiple percentage results (for example, a poll measuring a single multiple-choice preference), the result closest to 50% will have the highest margin of error. Typically, it is this number that is reported as the margin of error for the entire poll. Imagine poll reports as

- (as in the figure above)

As a given percentage approaches the extremes of 0% or 100%, its margin of error approaches ±0%.

Comparing percentages

Imagine multiple-choice poll reports as . As described above, the margin of error reported for the poll would typically be , as is closest to 50%. The popular notion of statistical tie or statistical dead heat, however, concerns itself not with the accuracy of the individual results, but with that of the ranking of the results. Which is in first?

If, hypothetically, we were to conduct a poll over subsequent samples of respondents (newly drawn from ), and report the result , we could use the standard error of difference to understand how is expected to fall about . For this, we need to apply the sum of variances to obtain a new variance, ,

where is the covariance of and .

Thus (after simplifying),

Note that this assumes that is close to constant, that is, respondents choosing either A or B would almost never choose C (making and close to perfectly negatively correlated). With three or more choices in closer contention, choosing a correct formula for becomes more complicated.

Effect of finite population size

The formulae above for the margin of error assume that there is an infinitely large population and thus do not depend on the size of population , but only on the sample size . According to sampling theory, this assumption is reasonable when the sampling fraction is small. The margin of error for a particular sampling method is essentially the same regardless of whether the population of interest is the size of a school, city, state, or country, as long as the sampling fraction is small.

In cases where the sampling fraction is larger (in practice, greater than 5%), analysts might adjust the margin of error using a finite population correction to account for the added precision gained by sampling a much larger percentage of the population. FPC can be calculated using the formula

...and so, if poll were conducted over 24% of, say, an electorate of 300,000 voters,

Intuitively, for appropriately large ,

In the former case, is so small as to require no correction. In the latter case, the poll effectively becomes a census and sampling error becomes moot.

See also

References

- Siegfried, Tom (2014-07-03). "Scientists' grasp of confidence intervals doesn't inspire confidence | Science News". Science News. Retrieved 2024-08-06.

- Isserlis, L. (1918). "On the value of a mean as calculated from a sample". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 81 (1). Blackwell Publishing: 75–81. doi:10.2307/2340569. JSTOR 2340569. (Equation 1)

Sources

- Sudman, Seymour and Bradburn, Norman (1982). Asking Questions: A Practical Guide to Questionnaire Design. San Francisco: Jossey Bass. ISBN 0-87589-546-8

- Wonnacott, T.H.; R.J. Wonnacott (1990). Introductory Statistics (5th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-61518-8.

External links

- "Errors, theory of", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Margin of Error". MathWorld.

as a sample of

as a sample of  respondents drawn from a population

respondents drawn from a population  reporting the percentage

reporting the percentage  of yes responses. We would like to know how close

of yes responses. We would like to know how close  , without having to conduct one. If, hypothetically, we were to conduct a poll

, without having to conduct one. If, hypothetically, we were to conduct a poll  to be normally distributed about

to be normally distributed about  , the true but unknown percentage of the population. The margin of error describes the distance within which a specified percentage of these results is expected to vary from

, the true but unknown percentage of the population. The margin of error describes the distance within which a specified percentage of these results is expected to vary from  ) either side of the true mean

) either side of the true mean  , a sample sized

, a sample sized  has a margin of error

has a margin of error

denotes the quantile (also, commonly, a

denotes the quantile (also, commonly, a  is the

is the  .

.

, and that all subsequent results

, and that all subsequent results  .

.

corresponds to the variance of a

corresponds to the variance of a  , that is, the interval

, that is, the interval  within which values of

within which values of  , that is,

, that is,  is undefined, as is

is undefined, as is  .

.

vs sample size n and confidence level γ. The arrows show that the maximum margin error for a sample size of 1000 is ±3.1% at 95% confidence level, and ±4.1% at 99%.

vs sample size n and confidence level γ. The arrows show that the maximum margin error for a sample size of 1000 is ±3.1% at 95% confidence level, and ±4.1% at 99%. illustrates the relationship between

illustrates the relationship between  at

at  and

and  at

at  . In the example, MOE95(0.71) ≈ 0.9 × ±3.1% ≈ ±2.8%.

. In the example, MOE95(0.71) ≈ 0.9 × ±3.1% ≈ ±2.8%. at

at  , calculate

, calculate  ,

,  to obtain the maximum margin of error for

to obtain the maximum margin of error for

as

as

(as in the figure above)

(as in the figure above)

. As described above, the margin of error reported for the poll would typically be

. As described above, the margin of error reported for the poll would typically be  , as

, as  is closest to 50%. The popular notion of statistical tie or statistical dead heat, however, concerns itself not with the accuracy of the individual results, but with that of the ranking of the results. Which is in first?

is closest to 50%. The popular notion of statistical tie or statistical dead heat, however, concerns itself not with the accuracy of the individual results, but with that of the ranking of the results. Which is in first?

, we could use the standard error of difference to understand how

, we could use the standard error of difference to understand how  is expected to fall about

is expected to fall about  . For this, we need to apply the sum of variances to obtain a new variance,

. For this, we need to apply the sum of variances to obtain a new variance,  ,

,

is the

is the  and

and  .

.

is close to constant, that is, respondents choosing either A or B would almost never choose C (making

is close to constant, that is, respondents choosing either A or B would almost never choose C (making