| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Fort King George" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

United States historic place

| Fort King George State Historic Site | |

| U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

Main façade of the reconstructed fort Main façade of the reconstructed fort | |

| |

| Location | McIntosh County, Georgia |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Darien, Georgia |

| Coordinates | 31°21′50″N 81°24′54″W / 31.36384°N 81.41493°W / 31.36384; -81.41493 |

| Area | 12 acres (4.9 ha) |

| Built | 1721 |

| Architect | Colonel John "Tuscarora Jack" Barnwell |

| Architectural style | Earthen palisade |

| NRHP reference No. | 71001101 |

| Added to NRHP | December 9, 1971 |

Fort King George State Historic Site is a fort located in the U.S. state of Georgia in McIntosh County, adjacent to Darien. The fort was built in 1721 along what is now known as the Darien River and served as the southernmost outpost of the British Empire in the Americas until 1727. The fort was constructed in what was then considered part of the colony of South Carolina, but was territory later settled as Georgia. It was part of a defensive line intended to encourage settlement along the colony's southern frontier, from the Savannah River to the Altamaha River. Great Britain, France, and Spain were competing to control the American Southeast, especially the Savannah-Altamaha River region.

Fort King George was a hardship post for troops assigned there. A total of 140 officers (including Col. Barnwell) and soldiers died, mostly from camp diseases such as dysentery and malaria, due to poor sanitation (none from battle). The soldiers made up The Independent Company of South Carolina, an "invalid" company of elderly British Regulars, one hundred in all, sent over from Great Britain. Their suffering was largely caused by their own poor health, and inadequate provisions due to poor funding. Problems such as periodic river flooding, indolence, starvation, excessive alcoholism, desertion, enemy threats, and potential mutiny exacerbated hardships at the fort.

The fort was a model for General James Oglethorpe when he set up his southern defense system for Georgia and established a settlement along the Altamaha River. In 1736, Oglethorpe brought Scottish colonists to settle the site of the abandoned Fort King George. They called their village New Inverness, later named Darien. That same year, Oglethorpe built Fort Frederica on Saint Simons Island. Oglethorpe borrowed extensively from ideas laid out earlier when South Carolina imperialists, such as John Barnwell, Joseph Bowdler, and Francis Nicholson, planned Fort King George as part of a defensive system. Oglethorpe decided to dismantle the fort in 1738.

Operated by the state of Georgia, the fort has been reconstructed and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is open to the public for historical tours. Structures include a blockhouse, officers' quarters, barracks, a guardhouse, baking and brewing house, blacksmith shop, moat, and palisades. The park's museum focuses on the 18th-century cultural history of the area, including the Guale, the 17th-century Spanish mission Santo Domingo de Talaje, the fort, and the Scottish colonists. An exhibit explains the 19th-century sawmilling at the site and the remains of two sawmills and ruins. Tabby cement ruins, based on a regional building material, also can be found on the property. Site staff offers living history programs year-round.

Background information

For nearly 200 years before the establishment of Georgia in 1733, Europeans of various nations had struggled to claim footholds in this vast territory. At one time, it was one of the most coveted regions in all of North America. Its bountiful river systems, the Altamaha, Ogeechee, and Savannah rivers, offered valuable conduits of transportation for empire building during the Age of Mercantilism. Europeans believed they could conquer its Native American peoples. The area's coastline had a labyrinth of barrier islands, mud shoals, sandbars, and impassable rivers that afforded a great natural barrier system for whoever controlled it.

Over time, this territory would become a "debatable land" for which Europe's three mightiest countries of the time: Spain, France, and Great Britain, all competed. This international rivalry brought many outcomes. First, the Spanish founded St. Augustine, Florida in 1565 to protect their shipping lanes for treasure-laden ships sailing up from South America.

As the French sought newer fur trade markets in the South, and ultimately the Southeast, French Louisiana was expanded in the late 17th century down the Mississippi and into the Gulf region. To curb French encroachment from the west, and to undermine Spain's traditional claims to areas north of Florida, the British colonists deemed it vital to expand and defend their southern borders, especially at the Savannah River. The resultant clash of European forces affected most of the regional Native American peoples, eventually destroying their traditional cultures and their independence.

The imperial struggle contributed in the 1720s to the establishment of Fort King George by the British, built at the headwaters of the Altamaha River, 3 miles (5 km) inland from Sapelo Island. Trade was also a key aspect of founding the fort. In 2011, an old map, dated 1721 and drawn by John Barnwell, was found in the fort's storeroom. It shows two roads from the fort: one leading north and the other along the river to a Muscogee (Creek) path, the tribe who were the desired trading partners. Spain sought to protect its rich harvest of precious metals in the Americas. France and England competed for control over the lucrative fur trade with the Native Americans. Additional resources such as timber, naval stores, and cash crops were also at stake for the British.

The British built Fort King George as a step toward settling the Altamaha River region. The British needed to control the river systems in order to control economic activities and commerce in the Southeast, especially that pertaining to the fur trade. The Altamaha River is one of the largest and far-reaching rivers in the region, and it allowed passage throughout the territory, especially to the powerful tribes of the Creek/Muskogee found west of the river system. Fort King George was part of a plan by the British to control the Altamaha and to secure economic imperial superiority in the Southeast.

Contest for empire in the Southeast

The Spanish were the first to arrive in the Southeast, first with explorers, then with the settlement of St. Augustine in present-day Florida in 1565. They started creating a mission system, converting the Native American tribes and using them as workers for agricultural production. The city became a base so that the Spanish could protect their treasure ships carrying gold and silver from the South. They used missions to expand the Catholic faith to the numerous tribes found in the Southeast. The converted Native Americans were incorporated into the Spanish system of repartimiento. They used an indigenous labor force capable of growing surplus grains for needy colonists in the Spanish-American Empire.

By the mid-17th century, dozens of Spanish missions controlled the southeastern coastline with thousands of Native Americans drawn into and around them. This system centered on missions accompanied with troops occupying presidios.

They created four mission provinces: Tumucua (interior northern Florida), Apalachee (northwestern Florida), Guale (Georgia coast north of the Altamaha River), and Mocama (from the Altamaha River south to the St. Johns River). The name Guale was possibly derived from a Native American chief of that name who was visited by Pedro Menéndez on St. Catherines Island in 1566. In that year, Menéndez established troops on that island. Santa Catalina de Guale would later become one of the largest and most productive missions by the mid-17th century.

Another successful mission was Santo Domingo de Talaje. Established sometime in the early 17th century, this mission was located on a large bluff 3 miles (5 km) up the north branch of the Altamaha River. Native Americans had inhabited the bluff for thousands of years. The English later used this site as the location for Fort King George in the 1720s.

Guale was threatened by the settlement of English Carolina immediately to the north, where Charlestown was established in 1670. Through the late seventeenth century, Carolinian forces and their Indian allies were successful at destroying the Spanish mission system. Throughout the 1670s and 1680s, they attacked and destroyed missions on Saint Catherines Island, St Simons Island, Cumberland Island, and several interior missions situated close to the coast. San Joseph de Sapala on Sapelo Island was destroyed by pirates in 1683, leading to Spanish abandonment of the Guale and Mocama provinces. Likewise, the British and allied forces reduced the Apalachee mission province during the first decade of the 18th century. The surviving mission Indians retreated and aggregated farther south until their remnants were situated just north of the Saint Augustine base near the St. Johns River. During the 1680s, the Carolina colonists had effectively driven the Spanish entirely from the modern Georgia coast. This campaign intensified hostilities between the Spanish and the English. It catalyzed British interest in settling the Savannah-Altamaha River region.

Further west, the French were moving down the Mississippi and into the Gulf region. In 1699 Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville founded Biloxi, and Mobile, the first capital of French Louisiana, was settled in 1702. From these bases, French fur traders planned to move eastward to incorporate regional tribes, especially the Creek, into their business enterprise. In 1718, they built Fort Toulouse at the forks of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers, in the heart of Creek country. This settlement, designed to take business from Carolina traders, was close to the Creek capital of Coweta. The British perceived it as a threat to their plans to control trade networks throughout the Southeast, especially among the Creek and Cherokee. The tribes' geographical proximity to the Carolina colony made their stability vital. The British intended to expand their trade westward to other Southeast tribes, such as the Choctaw and Chickasaw.

In 1702, during the War of Spanish Succession, Spain and France allied against Great Britain. South Carolinians were bordered by enemies to the south and west, which intensified the competition for Native American alliances. That year, the British colonists learned of their enemies' plan known as "Projet Sur La Caroline". Spanish Florida and French Louisiana allied forces intended to encircle South Carolina, especially with Native Americans. Officials in South Carolina convinced a large number of Yamasee to settle in the Beaufort, South Carolina area just north of the Savannah River basin. Good relations with the Yamasee ensured a protective buffer along the southern borders of the colony. The British also worked to maintain relations with the Creek and Cherokee tribes to the west. "Projet Sur La Caroline", while never implemented, left the South Carolina colonists with high anxiety for many years, and convinced officials of the necessity to maintain good Indian alliances.

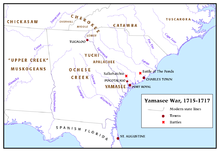

The Yamasee War of 1715–1717 broke out. This war started because of grave injustices carried out by Carolina traders against their Native American clients. For many years the traders had been systematically cheating the Indians in the fur trade by using bogus weights and measures, applying tough credit standards, severely indebting Native American suppliers, and taking Indian slaves for unpaid debts. Finally, the Yamasee turned on South Carolina and nearly destroyed the colony. Virginia's support and Cherokee warriors helped deflect the Yamasee attacks.

After the surviving Yamasee were expelled, they migrated to the St. Augustine area and cultivated a new alliance with the Spanish. South Carolina was left weak and vulnerable with no military buffer along its southern fringes, and the war alienated the Creek tribes to the west.

During this same period, the number of slaves in the colony was growing exponentially to the point that blacks outnumbered whites. The Spanish attempted to incite revolts by offering runaway slaves freedom and land in St. Augustine. They enrolled escaped slaves into the Spanish army.

In 1718, French colonists successfully attacked Pensacola, a settlement controlled by Spanish Florida. By this time, Spain and France had started the War of the Quadruple Alliance. The French success threatened Charlestown officials, who were convinced the French aimed to conquer the Southeast. They built Fort Toulouse had been built in the heart of Creek country earlier that year. The French were more active among the Creek and it appeared as though they had designs to expand further east.

Frightened and upset, the colonists finally exercised their own revolt. They rebelled against the ineffective rule of the Proprietors back in England. South Carolina, being a colony that was governed by eight proprietors from across the ocean, had suffered under a proprietary rule. The economy of the colony was hampered by runaway inflation caused by reckless economic policies and unreasonable restrictions on land ownership and trade regulation. Of graver concern were the issues related to defense. The colonists and their officials wanted greater protection from the enemies on their borders. The Proprietors were not willing to fund greater military development. In 1719, the colonists finally had enough. That year they ousted governor Robert Johnson, a proprietary governor, and chose James Moore, an outspoken opponent of the proprietary rule, as his replacement. Secondly, they sent Carolina planter John Barnwell to petition British Parliament that South Carolina become a Royal colony. It just so happened that Parliament had been taking a greater interest in the colony and the prospects of bringing it under royal dominion. Though the colony was having internal economic problems, overall it was one of the most productive in producing cash crops such as rice and indigo.

Furthermore, the fur trade in the colony, creating nearly a fifth of its exports to Great Britain, was quite lucrative for merchants back in England. Finally, the Yamasee War had made many English officials realize that the preservation of South Carolina was principal in defending the British North American Empire. Without the colony and its economic activities, the empire would be significantly weakened. Therefore, the petition was granted and in August 1720, South Carolina became a royal colony, though in name only as it would be nearly a decade later until the Proprietors were truly nullified and the colony was officially taken over by the Crown in practice.

Many felt Royal control would improve defensive measures for the colony. However, things did not vastly improve, though Parliament did seem receptive to newer ideas and token measures were taken to aid the colony's defense.

Colonel John "Tuscarora Jack" Barnwell had come to South Carolina in 1699 from northern Ireland. He was a man of considerable talent and leadership skills. He gained a reputation during his successful fight against the Tuscarora Indians in North Carolina in 1712. He owned a large and successful plantation in Beaufort, South Carolina. Barnwell was influential in the colony and proposed defensive measures for it. He developed a plan that became the inspiration for Georgia. It involved building a series of forts in strategic locations along South Carolina's frontiers in order to check French and Spanish expansion. These forts would serve as launching points for towns where soldiers would receive land allotments and other furnishings to facilitate settlement. The settlements would be used to expand the colony's territory and trade with the Natives.

During his visit to Parliament in 1720, Barnwell petitioned the British Board of Trade to help implement his plan. He emphasized the French threat as opposed to the Spanish one, since at the time the French seemed to be gaining considerable ground in the Southeast. Before the Board, Barnwell argued the strong possibility of a French attack on the colony and possible takeover of its southern borders, especially at the headwaters of the Altamaha River (called the River May by the French). To secure this area from French encroachment, his first proposal was for a fort to be built along the Altamaha River. The British Board of Trade approved of his plan in building this fort.

Due to the South Sea Bubble financial crisis, the British economy was in shambles. The government had minimal funds to spare and it showed in how Fort King George was operated, resourced, and funded. Barnwell requested "young, robust" soldiers to man the fort. He realized that the environment along the Altamaha would be a tough one. A long seasoning process was inevitable for the settlers and it would take time for them to adapt and properly outfit the settlement. Instead, the British sent elderly "invalids" from Colonel Felding's 41st Regiment. This Independent Company, thereafter known as His Majesty's Independent Company of Foot of South Carolina, was composed of three sergeants, three corporals, two drummers, and one hundred privates, all older men well past their prime. Governor Francis Nicholson of South Carolina was commissioned Captain of the Independent Company with Barnwell later being named Colonel. Initial officers included Lt. Joseph Lambert, Lt. John Emmenes, Ensigns Thomas Merryman and John Bowdler, Robert Mason as the surgeon, with Thomas Hesketh as Chaplain. Most of the soldiers and officers, including Barnwell, perished at the fort by 1727.

With the land allotments, tools, and farming implements, the soldiers were expected to establish a new settlement around the fort. This was the first British attempt to populate the Altamaha River region. It planned to have other settlers follow to the fort. Fort King George was highly significant in that it represented the culmination of a nearly 200-year European struggle to control the Southeast. By constructing the fort, the British dominated the river and its surrounding territory. It started a diplomatic feud with the Spanish, eventually leading to war between the two nations. The feud ended with the British success at the Battle of Bloody Marsh on St. Simons Island in 1742, several years after the fort had been abandoned. Though the fort was considered a failure in the near term, it ultimately contributed to Georgia's establishment and early success.

The Fort's construction and demise

From the time of its construction in 1721 to its abandonment in 1727, Fort King George was beset by one miserable experience after another. When the Independent Company embarked from London in November 1720, there may have been some room for optimism among the soldiers. Each was to receive many acres of land surrounding the fort, something unimaginable in the class-driven societies of England. Additionally, they would be given cattle and seed for growing crops to develop farms. Also, resources necessary for developing new homes and farms would be available. However, such possible optimism probably soon faded beneath a very harsh reality. All the soldiers contracted scurvy on the voyage over to South Carolina. Immediately upon landing the following March, the soldiers were placed in a hospital in Port Royal, South Carolina, where they would spend time recovering throughout the remainder of that year.

Left with no troops, Colonel Barnwell's only option was to enlist Coastal Scouts and civilians to help him construct the fort. Coastal Scouts were hardened seamen whose organization dated all the way back to the early 18th century in South Carolina. They were formed to establish some semblance of a navy for the colony. Their role was akin to marines, to patrol the waterways in scout boats up and down the coast between Beaufort and St. Augustine, and engage the enemy from their boats if necessary. They were also charged with the task of provisioning outlying forts on the frontier. Many scouts may have been former pirates as South Carolina was a den for many in the 1680s and 1690s when the colony started cracking down on piracy, arresting pirates and then offering them clemency in exchange for their oath to the King and services in the colony. Barnwell complained bitterly in his journal about all his troubles with them. He referred to them as "Continually (sic) sotting" and described them as "a wild Idle (sic) people" who were highly disobedient.

In one incident, during a bout of drunkenness, one prankster scout actually picked Barnwell up and heaved him over his shoulder pretending to carry Barnwell to his boat. Instead, he dropped the colonel in the water, forcing Barnwell to lie all night in wet clothes on his boat, something Barnwell later attributed to a sickness he soon contracted. Barnwell, ill-tempered, no doubt got his revenge somehow, but the incident goes to show there was little formal discipline in the wild frontiers of South Carolina. Barnwell needed the scouts to get the fort underway, and they were noted for being highly prone toward dissension and possible mutiny. Given the proximity to St. Augustine and the likeliness of desertion Barnwell, no doubt, had to be quite a bit more tolerant than most Colonels dealing with troops on the front lines of Europe.

Although their relationship was rough, Barnwell did manage to gain some progress during construction of the fort that summer in 1721. The fort's blockhouse was completed by the fall. The men had to go 3 miles (5 km) upriver to find adequate cypress trees to cut for the blockhouse's framework and siding. They nearly mutinied so Barnwell had to offer extra pay, and probably extra rum rations, to provide incentives for the men to go back out to cut more trees. Also, in addition to these accomplishments, Barnwell managed to sound out much of the river and charted a route down the coast to St. Simons Island. He was impressed with the obvious logistical advantage of this island and decided to propose moving the fort there. He was repeatedly denied by the legislature due to cost prohibitions.

By early 1722, the Independent Company was stationed at Fort King George. Within a year nearly half of them had died, mostly from diseases such as dysentery and malaria. The fort's officers periodically intimated in letters that the men were not well motivated. They had difficulty getting the men to tend to their lots, to build fences in order to entrap roaming cattle supplied for the troops and to grow crops. A lack of development made life even more miserable. A few soldiers deserted to St. Augustine. Still, others stayed through death from the elements was nearly a certainty. By later that year the fort's guardhouse was being called a hospital for "treating the sick".

Some excitement did occur periodically. In 1722, Indian agent Theophilus Hastings reported to the legislature that 170 Yamasee Indians were prepared to attack Fort King George. It seems, he indicated, that the Spanish "were playing their old game". Apparently, it was presumed that the Spanish were inciting the attack to test the fort's defensibility. Unfortunately, the records do not indicate whether or not the attack actually happened, however, if it did the fort must have survived unabated.

Later on that year, some unexpected visitors arrived at the fort. A company of "Switzers", Swiss soldiers, had deserted a settlement on the Mississippi River and had made their way to Fort King George where they sought asylum. Switzers were under the employ of the French government in their colony of Louisiana. These men were charged with the toilsome duty of digging canals and were often overworked and mistreated. This was probably the reason for their desertion. It also indicates that the French were quite aware of Britain's occupation at the mouth of the Altamaha and were apparently discussing it openly among all Louisiana settlers. Even though Carolina officials were having a hard time getting much-needed recruits at the fort, to replace the dying soldiers, they did not let all the Switzers stay there.

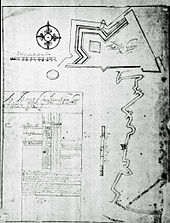

Instead, they allowed them to "disperse themselves into the colony as they pleased". However, they did request that any skilled Switzers, up to six total, stay behind to assist with construction. One of them obviously was a skilled artist and penned one of the fort's most descriptive drawings entitled, "A Plan of Fort King George at Allatamaha South Carolina". The drawing clearly displays intentions for the fort to be a triangular-shaped structure with only one bastion jutting out on the northwestern side, the only direction in which the fort could most likely be attacked by land. The eastern and southern sides of the fort were fully protected by natural wetlands thus making a land assault from those directions impossible. Also, the fort was designed to include a barracks, ninety feet long and fourteen feet wide, a guardhouse, an officers’ quarters, several indigenous huts, a very impressive parapet, a house of office (privy), and a dock for the scout boat, in addition to the blockhouse discussed previously.

The Spanish had been protesting the British occupation of the Altamaha ever since Fort King George was first built. In 1724, some Spanish envoys came to address grievances over the construction of the fort. However, they were not allowed to enter Fort King George because the Governor and commanders were worried that if they were to enter and inspect, the fort's security could be compromised. As such, the envoys were diverted to Charlestown where they had to express their grievances. Although Governor Nicholson welcomed them and treated them graciously, he did not accept their arguments and maintained the right of the British to settle the Altamaha River region. The Spanish were infuriated and over the next several years an intense game of diplomatic jousting ensued.

More drawings of the fort indicate that the fort was developing even though hardships seemed abundant. A 1726 drawing reveals the fort was fortified with a parapet that, in critical places, consisted of firing steps, a firing wall held against a breastwork made of earth, a palisade fence, and a moat. Fronting the river to the south, the fort was protected from naval assault by nine cannon emplacements. Each emplacement had a six-pounder cannon mounted on it. Also, several swivel guns were positioned throughout the fort, primarily around the gates. Most important, the fort was positioned on the closed end of a horseshoe-shaped bend in the river. Typical of the time period, this positioning prevented passing enemy ships a convenient firing off broadsides on the fort.

Instead, all ships would have to approach the fort bow (nose) first, thus making it harder for enemy sailors to position the boat sideways so as to fire through cannon ports at the fort. The fort was by all appearances a standard "pallisado" fort very typical of the type built on frontiers during the time period. They were primarily designed to be temporary until something more substantial could be built. Such forts, made from earthen materials and indigenous wood, were very practical for frontier defense as the materials were relatively easy to gather and transport to site. Also, these fortifications could easily be repaired if damaged, as materials were relatively available and indigenous to the area.

In 1724, Colonel Barnwell died at his plantation in Beaufort due to failing health, probably brought on by hardships during his tenure at the fort. Earlier, he had been declared to be Governor of the territory in addition to being the fort's commander. Though his dreams of seeing South Carolina bounded by a barrier of defensive settlements had been initiated, by the time of his death the reality of its successful fruition seemed bleak. Though dead, his legacy lived on later through General James Oglethorpe who borrowed heavily from Colonel Barnwell's ideas.

In late 1725 or early 1726, the fort burned under mysterious circumstances. It was suggested by the fort's reporting officer, Capt. Edward Massey, that the men stationed there may have been responsible for it, or at least, they did not rush to put the fires out "in hopes by the destruction of the Fort (sic) they should be delivered from the Miseries (sic) they had so long suffered." The soldiers probably desperately wanted to go back home or anywhere but Fort King George, three days away from Beaufort. If this was the case, their wishes did not come true. The fort was ordered rebuilt, this time with inferior cypress deal planking. Life did not improve.

Finally, in 1727, British Parliament ordered that Fort King George be abandoned and that the Independent Company be moved to Port Royal, South Carolina. In all, one hundred and forty soldiers and officers lost their lives at the fort, probably mostly from the diseases. The fort's officer, Lt. Emmenes, writing the justification of the fort's evacuation, set the unwholesome climate and the ineffectiveness of the fort's location. He stated that the fort would be no more useful to the safety of the colony if it had been "placed in Japan." Writing with a clear hint of indignation, Massey complained about the poor provisions and indicated grave concern that the men may mutiny if "they have no hopes of being relieved." Also, the fort was prone to periodic flooding which worsened conditions. Yamasee Indian raids were still occurring along the southern borders thus illustrating the failure of Fort King George's intent to secure the southern border.

Six years after its establishment the fort was abandoned with two lookouts left behind. South Carolina colonists and officials were gravely disappointed and even more so alarmed by the diplomatic sensitivities it had flared. Until Georgia was settled, expansionists were determined to re-establish some settlement on the Altamaha. By 1730, the issue of southern border defense had become an even more vexing and contentious one. Around this time, Governor Robert Johnson ordered that several towns be settled along the Altamaha in order to maintain Britain's claim to the area. Also, the South Carolina legislature relayed desires to have another fort or settlement built along the Altamaha. However, these measures never came to fruition. The demise of Fort King George once again brought an increase in anxieties over South Carolina's security.

Though the outlook may have seemed disappointing, there were a few silver linings. Fort King George actually did serve the colony well, not for its effectiveness, because it was largely ineffective, but for what it taught British imperialists. First, the hardships suffered by the Company of "Invalids" at Fort King George taught imperialists the necessity of peopling the Altamaha with a young, tough, and hardy people. It was a harsh, dangerous environment that could not be tamed by the weak-of-heart or faint-in-design. Settlers there would have to be able to withstand a harsh seasoning period. Also, being so far removed from civilization, Altamaha settlers would have to be thrifty, self-reliant, and industrious. Furthermore, these people would need incentives to develop a strong settlement and establish the industry. Secondly, diplomatic entanglements with the Spanish over Fort King George shifted much focus away from the French and problems of western defense, and more toward defenses on the southern frontier. As such, there was a greater focus on protecting the colony with fortresses and settlements along the coastal area, especially the barrier islands and their surrounding inlets. This is why General Oglethorpe later borrowed from Barnwell's idea for a fort to be built on St. Simons Island, where Fort Frederica, Oglethorpe's military base, was constructed in 1736.

Additionally, he added forts and settlements near Skidaway Island, near the mouth of the Ogeechee River, near the headwaters of the Altamaha, on Cumberland Island, and on Amelia Island. This coastal defense system was instrumental in the eventual successful defense of Georgia under Spanish attack in the 1740s. As such, the struggles and failures of Fort King George showed future empire builders a better way of defense, thus lending much credit to them for heeding the old adage, "those who do not learn from history are destined to repeat it." Oglethorpe and his fellow Georgians did not repeat the mistakes made in the handling of Fort King George, though they did largely stick to a similar plan of defense. However, the plan was implemented with a much more effective, well-planned, and well-supported strategy.

Fort King George's legacy for Georgia

During Fort King George's existence and demise, the South Carolina Legislature, Governor, and other imperialists started developing other alternatives for defending the colony's vulnerable southern border. During the 1720s, a Swiss gentleman, entrepreneur, and colonial adventurer Jean-Pierre de Pury started planning for a settlement of Swiss colonists in the area between the Savannah and Altamaha Rivers. Proclaiming its location to be in the Earth's ideal climate region, near 33 degrees latitude, he proposed that the name of the colony be Georgia. Though this settlement looked quite promising at first, it fell apart at the last moment due to a lack of adequate funding and support from the Proprietors. Eventually, however, Pury would settle Purrysburg, but it would be after Georgia's founding, and it was positioned north of the Savannah River rather than south of it. However, though the project did fail, it was successful in drawing greater attention throughout England to the area and proved especially enticing to English philanthropists looking to provide some sort of refuge for poor debtors.

This issue of defense coincided with a period of intense philanthropy in England. Certain members of Parliament and society aimed to improve the conditions of prisons in the country. One such gentleman, Sir James Edward Oglethorpe, while in Parliament, served on a committee to investigate conditions at prisons in the country. What he and his committee uncovered were horrific conditions. Many prisoners were released as a result but left with no employment and bereft of any livelihood. Oglethorpe was also interested in colonization and in defending Great Britain's vast holdings in North America.

From these two interests, the idea Georgia was spawned. Once a group of Trustees was formed, they decided to use debtor-prisoners to people the colony of Georgia, which was to be nestled in the Savannah-Altamaha River region, formerly known as the Margravate of Azilla, based upon a previously failed settlement scheme in 1717. This would allow them to escape the misfortune of Britain's harsh penal code and poverty, and to start over in a new land while simultaneously serving a valuable function for the British Crown. However, by the time recruitment efforts were complete, and the ships were loaded for the voyage to Georgia, not a single colonists was in debt. In fact, most were middle-class artisans and craftsmen whose interests in starting life new abroad was so great, the earlier plan for a debtors’ colony ended up being quite changed. Nevertheless, the colony was to be established as a haven for citizen-soldiers whose primary purpose was in defending the empire, while simultaneously contributing to her mercantilist economy as well with the production of cash crops, timber, furs, and naval stores. Lawyers were forbidden, for obvious reasons, as were , for security reasons.

The colony had many early growing pains that included a harsh seasoning period when many settlers died, struggles over whether to admit slaves, conflicts with South Carolina over fur trading rights, and disputes over everything from legalization of rum consumption to land rights. Still, Oglethorpe was quite adept at using his Native American neighbors to facilitate the colony's initial success.

He was also quite savvy at using the previous history as a guide. Oglethorpe knew he had to establish a successful settlement on the Altamaha and the surrounding areas. In 1735 he had Captain George Dunbar visit the ruins of Fort King George. Though his report on the site is vague (it only talks about surveyor lines being laid out, probably done so by the soldiers earlier at Fort King George), Oglethorpe's later actions demonstrate his unhappiness with the site.

Oglethorpe ordered the Highlanders to land at "Barnwell's Bluff", but later moved the settlement about 1 mile (2 km) farther up-river, probably due to the periodic flooding of the bluff and its proximity to the marsh, something attributable to malaria outbreaks in this time period Also, though it is not stated in records, it stands to reason that Oglethorpe was familiar with the earlier hardships endured at Fort King George. He may even have read Barnwell's journal and other records indicating the difficulties of settling the site on the Altamaha. The intense climate and harsh natural surroundings along the Altamaha, coupled with history, compelled Oglethorpe to seek a resilient group of people to settle the area. Also, he knew he had to use good logistics in how he established his fortification system along this vast stretch of coast, and that the Altamaha settlement would be a crucial cornerstone of his system.

The Georgia coast was as geologically unique in the early 18th century as it is to this day. Approximately one-third of all marshlands found on the east coast lie in coastal Georgia, which dips away from the continental shelf considerably farther than any other section of eastern North America. This produces a funnel effect that causes Georgia's coastline to ensure a greater concentration of tidal waters. The results are excessive fluctuations in tides, sometimes as high as 10 to 12 feet. Over years, this dramatic tidal shift has produced dynamic currents that have created a labyrinth of rivers, inlets, shoals, sounds, and sandbars contained behind ever-changing barrier islands. From a military perspective, due to its geographical complexity, the Georgia coast is the ideal place to build a defensive system.

In part due to this, Oglethorpe chose to use the barrier islands to his advantage for his defenses south of the Altamaha. Fort Frederica was placed on the inside side of St. Simons Island. On the south end of the Island, he also placed Fort St. Simons and Delegal's Fort. With these forts and the others positioned among the barrier islands, the main focus was to keep enemies out of the Altamaha river system. In an era long before highways, interstates, planes, or even adequate trails, controlling a river system was tantamount to controlling all the lands adjacent to it, and the region surrounding it. The Altamaha River bordered vast swamps full of valuable resources such as timber and precious pine sap for naval stores. Furthermore, it was a fine artery of travel far into the colony thus facilitating trade with distant Native American tribes.

This is exactly why Oglethorpe was very careful in the people he chose to settle and defend the Altamaha. Oglethorpe's military experience and training had taught him that Scottish Highlanders were among the toughest people in the world. For generations, they had forged a livelihood out of the mountainous ranges of the Highlands with its rocky, stubborn soils, and cruel weather patterns. The Scots had been united with the English into the United Kingdom since the Act of Union in 1707 however it was hardly a relationship of equals. Scottish people over many centuries had endured many cases of abuse from the English. When they weren't being exploited at home, Scottish troops were often hired mercenaries used to fight British wars abroad. With their broadswords, targes (pronounced targe, and used as a hand shield), and their dirks, they were the finest hand-to-hand combatants in the world. Though clannish, often insular, and politically unstable at home, the Scots were a force to be reckoned with on the battlefield, a perfect ingredient for frontier defense in the wildernesses along the Georgia coast where conventional warfare was not going to be the norm.

Thus, in late 1735 Oglethorpe sent Captain Dunbar and Lt. Hugh MacKay to the Highlands of Scotland to recruit potential settlers for Georgia's Altamaha frontier settlement. Many Scots were eager to come. Home life was rough due to English oppression and a feudal system that tied many Scottish families to small unproductive lands with limited opportunities, but North America offered plenty of hope. To lure them, the Trustees offered each family 50 acres (200,000 m) allotments, something most Scotsmen never even dreamed of owning in their homeland. Also, recruiters told the Scots each man would be armed with a firelock, a broadsword, and an axe. Recently, the English had passed laws disarming the Scots and making it unlawful for them to bear their traditional weapons. They were also to be given cattle, farming implements, and seed for crops. 177 Scots boarded the Prince of Wales in November 1735, en route to their new home in Georgia. Of these, most came from the Inverness area and were a part of the Chattan Confederation. They consisted of McIntoshes, McDonalds, MacBeans, MacKays, Frasers, Forbes, Clarks, Baillies, Cameron, and a host of other traditional Highland clan names. They disembarked at Savannah in early January 1736, and a short time later made their way to the new settlement on the Altamaha. Their settlement began at "Barnwell's Bluff", near the old ruins of Fort King George.

Oglethorpe visited the site the following February and was informed that the Scots had chosen to name their town Darien. This was to honor the previous Scottish settlement of Darien that had occurred earlier on the Isthmus of Panama in 1695, only to be subsequently destroyed by the Spanish. On his visit, Oglethorpe dressed in the traditional Highland kilt to show his respect for the Scots. As an additional show of respect, he refused comfortable sleeping quarters and preferred to sleep with the Highlander men out under a large oak tree.

One other issue probably addressed by Oglethorpe at this time was related to the place of settlement. He clearly must not have liked Lower Bluff where old Fort King George once was and at some point, he ordered the Scots to move their town further up the bluff (the modern-day site of the Darien bridge).

By the end of 1736, the Scots had moved their town and it began to thrive. Though there were definitely hardships along the way, the Scots of Darien went on to be Georgia's most useful settlers. In the ensuing years, they were integral in establishing a timber industry in Georgia as thousands of feet of lumber were shipped down the Altamaha River and processed at sawmills in Darien. Also, key Scottish figures in Georgia were instrumental in establishing better trade relations with the Creek Native Americans. There were numerous other commercial and social contributions given by the Scots at Darien. However, their most crucial role was that of a military nature. When the Spanish invaded Georgia out of Florida in July 1742, it was the Scots of Darien who were instrumental in defeating the Spanish at the Battle of Bloody Marsh on St. Simons Island, July 7, 1742. This successful battle helped bring to an end the struggle for empire in the Southeast and worked to cement Great Britain's hold on the area, as the Spanish never again really posed a serious threat to Georgia.

Over the next many generations, the Scots of Darien branched out into other frontiers of North America. Today, many families of Scottish ancestry owe their existence in the United States to those Scots who came to Darien, Georgia, a major gateway of Scottish settlement in the colonial era.

All these developments were made possible through the idea and existence of Fort King George. It served in some way as a blueprint toward the successful defense of Georgia, and consequently, inspired an economy and commerce that lent itself tremendously toward the colony's early success. Much of the colony's early structures were built out of cypress and yellow pine cut from swamps along the Altamaha River. This industry in timber became a staple element of Georgia's economy throughout the colonial period and on into the 20th century. It is ironic that Fort King George had to fail for Georgia to succeed. It was the lessons wrought from experiences at the frontier fort that helped guide Oglethorpe in his defensive efforts of the colony. Also, had Fort King George succeeded, the colony of South Carolina would have been expanded to the Altamaha River and South Carolina would have progressed from there, leaving little reason or justification for the colony of Georgia. Of even greater import are the lessons Fort King George taught about the type of settlers necessary on the Georgia frontier. When Oglethorpe and the Trustees developed plans for the colony, they envisaged a colony of citizen-soldiers whose dual roles of defense and development would achieve success. Although they did serve as soldiers, it was the early colonists’ role as citizens that counted most toward the growth of the colony's commerce and economy. Families, as opposed to soldiers alone, proved more likely to develop a devout personal interest in defending their new home, especially as the economy developed and homesteads were established. Finally, the town of Darien owes its origins to Fort King George. The site is where the town and its sawmilling tradition began.

Fort King George State Historic Site development

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Fort King George" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

For nearly two centuries after its evacuation, little was written about or known of Fort King George. Occasionally, there are references to a "Barnwell's Bluff", "Old Fort", or "First Landing", in the records, but Fort King George seemed to have faded into history. In the early 20th century there was groundbreaking research into the early history of the state, and much work was published about the early struggles for empire in the colonial era. In 1929 historian Verner Crane published his monumental book, The Southern Frontier, which comprehensively covered the period from 1670 to 1732. Other works, such as Herbert Bolton and Mary Ross's The Debatable Land helped shed light on the military struggles of the Southeast during the colonial period. Also, a plethora of articles on Georgia's early colonial struggles were written during this period. Crane's work about the contentious southern frontier was the first to describe the context for Fort King George and Barnwell's scheme of settling the Altamaha River region.

Sometime in the 1930s, Darien's local historian Bessie Lewis, then a history teacher, read Crane's monumental work. She made many trips to Charleston to study British Public Records for information about the former Fort King George. Lewis, or "Miss Bessie", as the locals fondly called her, discovered extensive material about the fort, including vital written records, descriptions, account ledgers, and several drawings with geographical details. This guided her in trying to locate the original site of the fort. Archeological excavations conducted later helped substantiate her claims. During the first excavations on the site in the 1940s, more than one dozen soldiers' graves were uncovered.

Miss Bessie and other locals organized the Fort King George Association and worked to have the site developed for a state historic site. In 1949, the state acquired the fort site from the Sea Island Company, a development organization. The Association envisioned a site with a museum and reconstructed replica of Fort King George, but little development took place. In the 1950s, the state installed a monument and headstones in the soldiers’ cemetery and a few picnic tables. The Association continued to lobby for reconstruction of the fort.

In the late 1960s, the Georgia Historical Commission acquired the site. Money was allotted for building a museum in 1967, and Fort King George Historic Site became a reality. In 1972, the site was taken over by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources (DNR) - the Parks, Recreation, and Historic Sites Division. In 1987, the site manager Ken Akins and the Lower Altamaha Historical Society teamed up in a drive to raise money to reconstruct the fort's blockhouse. With a matching fund from the DNR, the fort's reconstructed blockhouse was completed and dedicated in fall 1988. It was the center of the site's activities and programs until development in the late 1990s.

Georgia State Senator Renee Kemp, from 1999 to 2002, helped gain several hundred thousand dollars in capital investment for the site to reconstruct the fort's enlisted soldiers’ barracks, guardhouse, and officers’ quarters. Site staff re-constructed the fort's firing walls and firing steps. Over the years, site staff has added various other features. In 2004, with the installation of the fort's front and back gates, the fort was officially declared to be entirely reconstructed, something Miss Bessie had dreamed of more than five decades earlier but not lived to see.

Fort King George Historic Site has become one of Georgia's premier tourist attractions, with more than 30,000 visitors annually. Site personnel provide a wide range of living history programs dealing with Colonial Life and Military Science.

See also

- Georgia State Parks

- Darien, Georgia

- McIntosh County, Georgia

- Fort Frederica National Monument

- Fort St. Andrews

- Fort Barrington

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- William R, Mitchell Jr.; Nancy O'Hare (May 17, 1971). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Fort King George". National Park Service. with four photos from 1970

- "America and West Indies: April 1738." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 44, 1738. Ed. K G Davies. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1969. 59-74. British History Online Retrieved 1 July 2021

- Manucy (1945), p. 14

- Oatis (2004), p. 16

- Crane (1929), pp. 47–49

- Gregory A Waselkov, pp. 23-32

- Louie Brogdon, "Artifacts help bring coastal history to life", (AP), Brunswick, Georgia, May 2011, in News From Indian Country. Accessed November 7, 2011.

- Cook (1990), pp. 1–4, 9, 17

- Crane (1929), pp. 233–234, 241

- Corkran (1967), p. 69

- Corkran (1967), pp. 16–18

- Bolton & Ross (1925), pp. 10–18

- Bolton & Ross (1925), p. 9

- Worth (1995), p. 13

- Worth (1995), pp. 30–36, 39–44

- Jefferies & Moore (2008), pp. 58–60

- Crane (1929), pp. 47–50

- Oatis (2004), pp. 42, 67, 215

- Oatis (2004), pp. 50–53, 58–59, 213–222

- Corkran (1967), pp. 61–81

- Crane (1929), pp. 71–73, 88, 91, 162

- Oatis (2004), pp. 58–59, 63, 80

- Bolton & Ross (1925), p. 62

- Oatis (2004), pp. 168–186

- Bolton & Ross (1925), pp. 64–65

- Oatis (2004), pp. 96–99, 106–107

- Oatis (2004), pp. 220–225

- Crane (1929), pp. 115, 208, 214–220

- Weir (1997), pp. 90–101

- Oatis (2004), pp. 162–166

- For more background on John Barnwell, see Barnwell (1969)

- Crane (1929), pp. 220, 229–231

- Rowland, Moore & Rogers (1996), p. 103

- Colonial Office Library (CO) 5:400 South Carolina Entry Book 1720–1730 August 3, 1720

- Historical Collections of South Carolina vol 1, p. 254

- Foote (1961), pp. 195–196

- Crane (1929), pp. 235–237

- Williams, 183-185

- The only recorded uniform materials of the soldiers can be found in Barnwell's List of Necessities at British Public Records of South Carolina Board of Trade vol 1a, p. 11

- Crane (1929), pp. 233–234

- ^ Historical Collections of South Carolina vol 1, p. 257

- Barnwell (1926), pp. 193–195

- Ivers (1972), pp. 121–122

- Barnwell (1926), pp. 197–198

- August 3, 1722

CJ 1722-24 vol 2, pp. 71-72 - William Foote, "The American Independent Companies of the British Army", (UMI Dissertation Services, 1966), 306-307

- CO 5/425 LJ May, 1721-Feb. 1723, Dec. 5, 1722

- January 23, 1723 CJ 1722-24 vol 2, p. 148.

- December 8, 1722 CO 5/425 LJ May, 1721-Feb. 1723

- Cook (1990), pp. 48–49

- Feb. 27, 1724 BPRO SC vol 11, p. 32

- September 10, 1725

- BPRO SC vol 10, pp. 335-36

- Historical Collections of South Carolina vol 1, p. 236

- December 20, 1722 Historical Collections of South Carolina vol 3, p. 280

- May 24, 1722 CJ 1722-1724 v. 2 p.2

- Feb. 17, 1722 CO 5/425 LJ May, 1721-Feb. 1723

- Barnwell (1969), p. 16

- Crane (1929), pp. 251, 229

- June 19, 1722 C.O. 5/425 LJ May, 1721-Feb. 1723

- Crane (1929), pp. 245

- C.O. 5:360, C 2 (enclosure)

- Crane (1929), pp. 245–246

- Crane (1929), p. 247

- April 26, 1727 BPRO vol 12, pp. 247-250 Historical Collections of South Carolina vol 1, p. 292

- Historical Collections of South Carolina v. 1 p. 292-293

- August 10, 1731COSC v. 5 p. 31

- November 14, 1731COSC vol 15, p. 38

- Date Unknown COSC 1730-34 vol 5, p. 451

- Crane (1929), pp. 283–287

- Crane (1929), pp. 210–214, 303–325

- Coleman (1991), pp. 16–18

- Gober Temple & Coleman (1961), pp. 65–70

- Kenneth Coleman, Colonial Records of Georgia, v. ??, George Dunbar to James Ogelthorpe, Jan. 23, 1734/35, p. 193

- Ivers (1974), pp. 51, 136

- Schuttle (2001)

- Parker (1997), pp. 23, 34–35

- Schaitberger (n.d.), pp. 5–12

- Sullivan (2001), p. 17

- Schaitberger (n.d.), pp. 18–22

- Parker (1997), pp. 39, 53–55

- Lewis (2002), pp. 11–19

- Parker (1997), pp. 56–57, 101–105

- Cashin (1992)

- Ivers (1974), pp. 45–46

- Sullivan (2001), pp. 144–149

- Floyd, Joseph (2013). "Ghosts of Guale: Sugar Houses, Spanish Missions, and the Struggle for Georgia's Colonial Heritage". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 97 (4): 387.

Sources cited

- Barnwell, Joseph W., ed. (1926). "Fort King George – Journal of Col. John Barnwell". South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine. 27.

- Barnwell, Stephen B. (1969). The Story of An American Family. Marquette: Privately printed.

- Bolton, Herbert; Ross, Mary (1925). The Debatable Land: A Sketch of the Anglo-Spanish Contest for the Georgia Country. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Cashin, Edward (1992). Lachlan McGillivray, Indian Trader: The Shaping of the Southern Colonial Frontier. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- Cook, Jeannine (1990). "Fort King George: Step One to Statehood". The Darien News.

- Coleman, Kenneth (1991). A History of Georgia. The University of Georgia.

- Corkran, David H. (1967). The Creek Frontier, 1540–1783. New York, NY: Norman Press.

- Crane, Verner (1929). The Southern Frontier.

- Foote, William (1961). "The South Carolina Independents". The South Carolina Historical Magazine. 112.

- Gober Temple, Sarah B.; Coleman, Kenneth (1961). Georgia Journeys: Being an Account of the Lives of Georgia's Original Settlers and Many Other Early Settlers from the Founding of the Colony in 1732 until the Institution of Royal Government in 1754. Athens, GA: University of Georgia.

- Hughson, Shirley Carter (1992). The Carolina Pirates and Colonial Commerce, 1670–1740. Spartanburg: The Reprint Company.

- Ivers, Larry (1972). "Scouting the Inland Passage, 1685–1737". The South Carolina Historical Magazine. 73.

- Ivers, Larry (1974). British Drums on the Southern Frontier. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina. ISBN 9780807812112.

- Jefferies, Richard; Moore, Christopher R. (April 26, 2008). Recent Mission Period Archaeological Investigations on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Spring Meeting of the Society for Georgia Archaeology Fernbank Museum of Natural History Atlanta, Georgia.

- Lewis, Bessie (2002). "They Called Their Town Darien". The Darien News.

- Manucy, Albert C., ed. (1945). The History of Castillo de San Marcos & Fort Matanzas: From Contemporary Narratives and Letters. Washington, DC: National Park Service.

- Oatis, Steven J. (2004). A Colonial Complex: South Carolina's Frontiers in the Era of the Yamasee War. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Parker, Anthony (1997). Scottish Highlanders in Colonial Georgia: The Recruitment, Emigration, and Settlement at Darien. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia.

- Rowland, Lawrence Sanders; Moore, Alexander; Rogers, George C. (1996). The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina: Volume 1, 1514–1861. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

- Schaitberger, Lillian B. (n.d.). The Scots of McIntosh. Darien, GA: The Lower Altamaha Historical Society.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Schuttle, Taylor (2001). A Guide to a Georgia Barrier Island. St. Simons: Watermarks Publishing.

- Sullivan, Buddy (2001). Early Days on the Georgia Tidewater: The Story of McIntosh County and Sapelo. Darien, GA: Darien Printing & Graphics.

- Thomas, David Hurst (1992). "The Spanish Mission Experience in La Florida". In Jeannine Cook (ed.). Columbus and the Land of Ayllon: The Exploration and Settlement of the Southeast. Darien, GA: The Lower Altamaha Historical Society.

- Waselkov, Gregory A. (1996). The French on the Southern Colonial Frontier. Drums Along the Altamaha: a Historic Symposium Held at Fort King George State Historic Site November 10, Darien, Ga.

- Weir, Robert M. (1997). Colonial South Carolina: A History. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

- Williams, W. R. (1932). "British-American Officers 1720 to 1763". The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine. 33.

- Worth, John (1995). "The Struggle for the Georgia Coast: an 18th Century Spanish Retrospective of Guale and Mocama". Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. 75.

External links

- Fort King George Historic Site - official site at GA State Parks & Historic Sites

- [REDACTED] Media related to Fort King George (Georgia) at Wikimedia Commons

- Forts in Georgia (U.S. state)

- History of the Thirteen Colonies

- Military facilities on the National Register of Historic Places in Georgia (U.S. state)

- State parks of Georgia (U.S. state)

- History museums in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Museums in McIntosh County, Georgia

- Military and war museums in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Government buildings completed in 1721

- Military installations established in the 1720s

- British forts in the United States

- Colonial forts in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Protected areas established in 1949

- Protected areas of McIntosh County, Georgia

- Forts on the National Register of Historic Places in Georgia (U.S. state)

- National Register of Historic Places in McIntosh County, Georgia

- 1721 establishments in the British Empire