| Hawaiʻi Sign Language | |

|---|---|

| Hoailona ʻŌlelo o Hawaiʻi | |

| Native to | United States |

| Region | Hawaii |

| Native speakers | 40 (2019) Moribund; a few elderly signers are bilingual with the dominant ASL. It may be that all speak mixed HSL/ASL, a.k.a. Creolized Hawai‘i Sign Language (CHSL). |

| Language family | Isolate |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | hps |

| Glottolog | hawa1235 |

| ELP | Hawai'i Sign Language |

Hawaiʻi Sign Language or Hawaiian Sign Language (HSL; Hawaiian: Hoailona ʻŌlelo o Hawaiʻi), also known as Hoailona ʻŌlelo, Old Hawaiʻi Sign Language and Hawaiʻi Pidgin Sign Language, is an indigenous sign language native to Hawaiʻi. Historical records document its presence on the islands as early as the 1820s, but HSL was not formally recognized by linguists until 2013.

Although previously believed to be related to American Sign Language (ASL), the two languages are unrelated. In 2013, HSL was used by around 40 people, mostly over 80 years old. An HSL–ASL creole, Creole Hawaiʻi Sign Language (CHSL), is used by approximately 40 individuals in the generations between those who signed HSL exclusively and those who sign ASL exclusively. Since the 1940s, ASL has almost fully replaced the use of HSL on the islands of Hawaiʻi and CHSL is likely to also be lost in the next 50 years. HSL is considered critically endangered.

History

Although HSL is not itself a pidgin, it is commonly known as Hawaiʻi Pidgin Sign Language or Pidgin Sign Language due to its historical association with Hawaiʻi Pidgin. Linguists who have begun to document the language and community members prefer the name Hawaiʻi Sign Language, and that is the name used for it in ISO 639-3 as of 2014.

Village sign use, by both Deaf and hearing, is attested from 1820. There is the possibility of influence from immigrant sign later that century, though HSL has little in common today with ASL or other signed and spoken languages it has come in contact with. The establishment of a school for the deaf in 1914 strengthened the use of sign, primarily HSL, among the students. A Chinese-Hawaiian Deaf man named Edwin Inn taught HSL to other d/Deaf adults and also stood as president of a Deaf club. However, the introduction of ASL in 1941 in place of purely oral instruction resulted in a shift from HSL.

Recognition

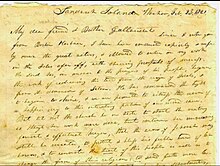

HSL was recognized by linguists on March 1, 2013, by a research group from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. The research team found a letter from Reverend Hiram Bingham to Reverend Thomas H. Gallaudet from Feb. 23, 1821. The letter described several instances of deaf Kānaka Maoli communicating to Bingham in their own sign language. The initial research team interviewed 19 Deaf people and two children of Deaf parents on four islands. Eighty percent of HSL vocabulary is different from American Sign Language.

Some reports on HSL claimed it to be "the first new language to be uncovered within the United States since the 1930s," or that it may be the "last undiscovered language in the country."

Prior to 2013, HSL was largely undocumented. HSL is at risk of becoming dormant due to its low number of signers and the adoption of ASL.

HSL and ASL Comparisons

HSL shares few lexical and grammatical components with ASL. While HSL follows subject, object, verb (SOV) typology, ASL follows subject, verb, object (SVO) typology. HSL does not have verbal classifiers – these were previously thought to be universal in sign languages, and ASL makes extensive use of these. HSL also has several entirely non-manual lexical items, including verbs and nouns, which are not typical in ASL.

HSL Today

An estimated 15,857 of the total 833,610 residents of Hawaiʻi (1.9%) are audiologically deaf. Among this population, ASL is now significantly more common than HSL. There are a handful of services available to help d/Deaf Hawaiian residents learn ASL and also for those who wish to learn ASL to become interpreters, such as the Aloha State Association of the Deaf and the American Sign Language Interpreter Education Program. Equivalent services for HSL are nearly non-existent, partially because some members of the Deaf community in Hawaiʻi have felt that it is not worth preservation.

Researchers at the Sign Language Documentation Training Center and the University of Hawaiʻi have begun projects to document HSL. Their first goal is to teach graduate students and other linguists how to document HSL and other small sign languages used in Hawaiʻi. Their second goal is to have 20 hours of translated HSL on video. As of 2016, a dictionary and video archive of speakers had been created.

References

- ^ Hawaiʻi Sign Language at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023) [REDACTED]

- ^ "Hawai'i Sign Language". Endangered Languages Project. Archived from the original on Dec 7, 2023.

- ^ "Linguists say Hawaii Sign Language found to be distinct language". Washington Post. 1 March 2013. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- Wittmann, Henri (1991). "Classification linguistique des langues signées non vocalement." Revue québécoise de linguistique théorique et appliquée 10:1.215–88.

- ^ Lambrecht, Earth & Woodward 2013.

- ^ Rarrick & Labrecht 2016.

- Mcavoy, A. (2013, March 01). Hawaii Sign Language found to be distinct language. Associated Press. Retrieved April 30, 2017

- ^ Clark et al. 2016.

- ^ Wiecha, Karin (March 8, 2013). "Linguists Discover Existence of Distinct Hawaiian Sign Language". The Rosetta Project. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

- Ethnologue

- "Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: hps". Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ^ "Mānoa: Research team discovers existence of Hawaiʻi Sign Language | University of Hawaii News". manoa.hawaii.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

- Lincoln, M. (2013, March 01). Nearly lost language discovered in Hawaiʻi. Retrieved April 30, 2017

- ^ Clark, B., Lambrecht, L., Rarrick, S., Stabile, C., & Woodward, J. (2013). DOCUMENTATION OF HAWAIʻI SIGN LANGUAGE: AN OVERVIEW OF SOME RECENT MAJOR RESEARCH FINDINGS . University of Hawaiʻi, 1-2. Retrieved April 30, 2017

- Wilcox, D. (n.d.). Linguists rediscover Hawaiian Sign Language Archived 2018-11-08 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 30, 2017

- ^ Perlin, Ross (August 10, 2016). "The Race to Save a Dying Language". The Guardian.

- "Endangered Languages: Key Terms". The Linguists. Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- Hornsby, Michael (December 2012). "Sleeping languages: Exercises on language revival" (PDF). Languages in Danger. Adam Mickiewicz University. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- Browning, Daniel (7 July 2017). "NAIDOC Week: Indigenous languages aren't dead, just sleeping — and this is why they matter". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Tanigawa, N. (2016, NOV 22). Hawai'i Sign Language Still Whispers. Retrieved May 1, 2017

- HMSA. "sign preservation". islandscene.com. Retrieved 2021-08-20.

- "Hawaii Sign Language". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- "American Sign Language". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- Rarrick 2015.

- Smith, Sarah Hamrick, Laura Jacobi, Patrick Oberholtzer, Elizabeth Henry, Jamie. "LibGuides. Deaf Statistics. Deaf population of the U.S." libguides.gallaudet.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Signs of Self". www.signsofself.org. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

- Rarrick & Wilson 2016.

- "Documentation of Hawaii Sign Language: Building the Foundation for Documentation, Conservation, and Revitalization of Endangered Pacific Island Sign Languages". Endangered Languages Archive at SOAS University of London. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

Bibliography

- Lambrecht, Linda; Earth, Barbara; Woodward, James (March 3, 2013), History and Documentation of Hawaiʻi Sign Language: First Report, University of Hawaiʻi: 3rd International Conference on Language Documentation and Conservation, hdl:10125/26133

- Rarrick, Samantha (2015). "A Sketch of Handshape Morphology in Hawai'i Sign Language". University of Hawai'i at Manoa Working Papers in Linguistics. 46 (6). hdl:10125/73260.

- Clark, Brenda; Rarrick, Samantha; Rentz, Bradley; Stabile, Claire; Woodward, James; Uno, Sarah (2016). "Uncovering Creole Hawaiʻi Sign Language: Evidence from a case study". Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research (TISLR). 12.

- Rarrick, Samantha; Labrecht, Linda (2016). "Hawaiʻi Sign Language". The SAGE Deaf Studies Encyclopedia: 781–785. doi:10.4135/9781483346489.n247. hdl:10072/394832.

- Rarrick, Samantha; Wilson, Brittany (2016). "Documenting Hawai'i's Sign Languages". Language Documentation & Conservation. 10: 337–346. hdl:10125/24697. ISSN 1934-5275.

External links

- Hawaii Links & Resources. Signs of Self: Independent Living Services for People who are Deaf, Hard of Hearing, or Deaf-Blind

- Rarrick, Samantha & Brittany Wilson. 2015. Documenting Hawai'i's Sign Language.

- ELAR archive of Documentation of Hawaii Sign Language

- Hawai'i Sign Language

- Hawaiian Sign Language vs. American Sign Language

| State of Hawaii | |

|---|---|

| Honolulu (capital) | |

| Topics | |

| Society | |

| Main islands | |

| Northwestern Islands | |

| Notable communities | |

| Counties | |

| Pre-statehood history | |

| Languages of Hawaii | |

|---|---|

| Official languages | |

| Pidgins and Creole languages | |

| Sign languages | |

| Sign language | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language families |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| By region |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASL | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Extinct languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Linguistics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fingerspelling | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Writing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Language contact |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Media | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Persons | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Organisations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellaneous | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ^a Sign-language names reflect the region of origin. Natural sign languages are not related to the spoken language used in the same region. For example, French Sign Language originated in France, but is not related to French. Conversely, ASL and BSL both originated in English-speaking countries but are not related to each other; ASL however is related to French Sign Language.

^b Denotes the number (if known) of languages within the family. No further information is given on these languages. ^c Italics indicate extinct languages. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||