Iron gall ink (also known as common ink, standard ink, oak gall ink or iron gall nut ink) is a purple-black or brown-black ink made from iron salts and tannic acids from vegetable sources. It was the standard ink formulation used in Europe for the 1400-year period between the 5th and 19th centuries, remained in widespread use well into the 20th century, and is still sold today.

Preparation and use

The ink was traditionally prepared by adding some iron(II) sulfate (FeSO4) to a solution of tannic acid, but any iron ion donor can be used. The gallotannic acid was usually extracted from oak galls or galls of other trees, hence the name. Fermentation or hydrolysis of the extract releases glucose and gallic acid, which yields a darker purple-black ink, due to the formation of iron gallate.

The fermented extract was combined with the iron(II) sulfate. After filtering, the resulting pale-grey solution had a binder added to it (most commonly gum arabic) and was used to write on paper or parchment. A well-prepared ink would gradually darken to an intense purplish black. The resulting marks would adhere firmly to the parchment or vellum, and (unlike india ink or other formulas) could not be erased by rubbing or washing. The marks could only be erased by scraping a thin layer off the writing surface.

Chemistry

By mixing tannin with iron sulfate, a water-soluble ferrous tannate complex is formed. Because of its solubility, the ink is able to penetrate the paper surface, making it difficult to erase. When exposed to air, it converts to a ferric tannate, which is a darker pigment. This product is not water-soluble, contributing to its permanence as a writing ink.

The darkening process of the ink is due to the oxidation of the iron ions from ferrous (Fe) to ferric (Fe) state by atmospheric oxygen. For that reason, the liquid ink needs to be stored in a well-stoppered bottle, and often becomes unusable after a time. The ferric ions react with the tannic acid or some derived compound (possibly gallic acid or pyrogallol) to form a polymeric organometallic compound.

While a very effective ink, the formula was less than ideal. Iron gall ink is acidic. Depending on the writing surface being used, iron gall ink can have unsightly "ghost writing" on the obverse face of the writing surface (most commonly parchment or paper). Ultimately it may eat holes through the surface it was on. This is accelerated by high temperature and humidity. However, some manuscripts written with it, such as the Book of Magical Charms, have survived hundreds of years without it damaging the paper on which it was used.

History

The earliest recipes for oak gall ink come from Pliny the Elder, and are vague at best. Many famous and important manuscripts have been written using ferrous oak gall ink, including the Codex Sinaiticus, the oldest, most complete Bible currently known to exist, thought to be written in the middle of the fourth century. Due to the ease of making iron gall ink and its quality of permanence and water resistance this ink became the favored one for scribes in the European corridor as well as around the Mediterranean Sea. Surviving manuscripts from the Middle Ages as well as the Renaissance bear this out as the vast majority are written using iron gall ink, the balance being written using lamp black or carbon black inks. Many drawings by Leonardo da Vinci were made with iron gall ink. Laws were enacted in Great Britain and France specifying the content of iron gall ink for all royal and legal records to ensure permanence in this time period as well.

The popularity of iron gall ink traveled around the world during the colonization period and beyond. The United States Postal Service had its own official recipe that was to be used in all post office branches for the use of their customers. It was not until the invention of chemically-produced inks and writing fluids in the latter half of the 20th century that iron gall ink fell from common use.

Waning use

The permanence and water-resistance of the iron and gall-nut formula made it the standard writing ink in Europe for over 1,400 years, and in America after European colonisation. Its use and production started to decline only in the 20th century, when other waterproof formulas (better suited for writing on paper) became available. Today, iron gall ink is manufactured by a small number of companies and used by fountain pen enthusiasts and artists, but has fewer administrative applications.

While its use is waning globally, it is still required (along with Klaf) by Jewish Halakha for various religious documents, such as a Get, a Ketubah, Mezuzahs, and Torah Scrolls.

Fountain pens

Traditional iron gall inks intended for dip pens are not suitable for fountain pens which operate on the principle of capillary action. Ferro-gallic deposit accumulation in the feed system can clog the small ink passages in fountain pen feeds. Further, very acidic traditional iron gall inks intended for dip pens can corrode metal pen parts (a phenomenon known as redox reaction/flash corrosion). These phenomena can destroy the functionality of fountain pens.

Instead, modern surrogate iron gall formulas are offered for fountain pens, such as blue-black bottled inks by Lamy (discontinued in 2012), Montblanc (discontinued in 2012), Chesterfield Archival Vault (discontinued in 2016), Diamine Registrar's Ink, Ecclesiastical Stationery Supplies Registrars Ink, Hero 232, and Organics Studios Aristotle Iron Gall. Other manufacturers offer besides blue-black other colored iron gall inks such as Gutenberg Urkundentinte G10 Schwarz (certificate ink G10 black), KWZ Iron Gall inks, Platinum Classic inks, Rohrer & Klingner "Salix" (blue-black) and "Scabiosa" (purplish-grey) inks, and Stipula Ferrogallico inks for fountain pens.

These modern iron gall inks contain a small amount of ferro-gallic compounds and are also more likely to have a formulation which is stoichiometrically optimised. Historical inks often contained excess acid which was not consumed in the oxidation of the ferro-gallic compounds. Modern formulations also tend to use hydrochloric acid whereas many historical inks used sulfuric acid. Hydrochloric acid is a gas in solution, which will evaporate. As a result, modern fountain pen iron gall inks are less likely to damage paper than historical inks and are gentler for the inside of a fountain pen, but can still cause problems if left in a pen for a long period. Manufacturers or retailers of modern iron gall inks intended for fountain pens sometimes advise a more thorough than usual cleaning regimen – which requires the ink to be flushed out regularly with water – to avoid clogging or corrosion on delicate pen parts. For more thoroughly cleaning iron gall ink out of a fountain pen, sequential flushes of the pen with water, diluted vinegar or citric acid (to flush out residual iron gall compounds), water, diluted ammonia (if needed to flush out residual colour dye stains), then finally water are often recommended.

The colour dye in these modern iron gall formulas functions as a temporary colourant to make these inks clearly visible whilst writing. The ferro-gallic compounds through a gradual oxidation process cause an observable gradual colour change to grey/black whilst these inks completely dry and makes the writing waterproof. The colour-changing property of the ink also depends on the properties of the used paper. In general, the darkening process will progress more quickly and visibly on papers containing relatively high bleaching agent residues.

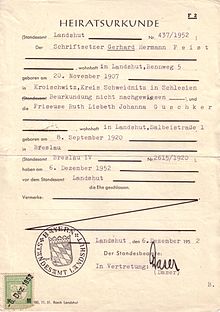

Though not in mainstream 21st-century use like dye-based fountain pen inks, modern iron gall inks are still used in fountain pens where permanence is required. In the United Kingdom the use of special blue-black archival quality Registrars' Ink containing ferro-gallic compounds is required in register offices for official documents such as birth certificates, marriage certificates, death certificates and on clergy rolls and ships' logbooks. In Germany the use of special blue or black urkunden- oder dokumentenechte Tinte or documentary use permanent inks is required in notariellen Urkunden (Civil law notary legal instruments).

German regulation for Urkundentinte inks (1933)

- In a litre of ink there must be at least 27 g of tannic acid and gallic acid, and at least 4 g of iron content. The maximum iron content is 6 g/L.

- After 14 days' storage in a glass container the ink must not have stained the glass or show sedimentation.

- Eight-day-old writings, after washing with water and alcohol, must remain very dark.

- The ink must flow easily from the pen, and may not be sticky even immediately after drying.

U.S. government "standard ink" formula (1935)

- 11.7 g tannic acid

- 3.8 g gallic acid C

6H

2(OH)

3COOH - 15 g iron(II) sulfate

- 3 cm hydrochloric acid (used to prevent sediment forming)

- 1 g carbolic acid (phenol, C

6H

5OH, biocide) (preservative) - 3.5 g china-blue aniline dye (water-soluble)

- 1000 cm distilled water

The Popular Science iron gall writing ink article also mentions methyl violet dye could be used to make a violet iron gall ink without revealing the amount and soluble nigrosine dye for an immediate black iron gall ink. To avoid the toxic carbolic acid biocide used as a preservative in the U.S. government "standard ink" formula, 2 g salicylic acid C

6H

4(OH)COOH can be used as a safer biocide alternative to prevent mold in the ink bottle. Both preservatives are enhanced by lowering the pH-value (acidifying the ink by adding hydrochloric acid).

Indian Standard 220 (1988)

In India, the IS 220 (1988): Fountain Pen Ink – Ferro-gallo Tannate (0.1 percent iron content) Third Revision standard, which was reaffirmed in 2010, is in use. This Indian Standard was adopted by the Bureau of Indian Standards on 21 November 1988, after the draft finalized by the Inks and Allied Products Sectional Committee had been approved by the Chemical Division Council. IS 220 prescribes the requirements and the methods of sampling and tests for ferrogallo tannate fountain pen inks containing not less than 0.1 percent of iron.

Annex M stipulates that the IS 220 reference ink shall be prepared according to the following formula:

- 4.0 g tannic acid

- 1.5 g gallic acid

- 5.5 g ferrous sulfate crystals FeSO

4·7H

2O - 5.0 g concentrated hydrochloric acid

- 5.0 g dye, ink blue (see IS 8642 : 1977)

- provisional dye (for inks other than blue black) As advised by supplier.

- phenol (see IS 538 : 1968)

- distilled water (to make the total volume one litre).

The IS 220 reference ink shall not be used for more than one month after the date of preparation and shall be stored in amber-coloured reagent bottles (see IS 1388 : 1959).

See also

References

- Diringer, David (1 March 1982). The Book Before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental. Dover Publications. pp. 551–2.

- Flemay, Marie (21 March 2013). "Iron Gall Ink". Traveling Scriptorium. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Eusman, Elmer (1998). "Iron gall ink – Chemistry". The Iron Gall Ink Website. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Fruen, Lois (2002). "Iron Gall Ink". The Real World of Chemistry. Kendall/Hunt Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7872-9677-3. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016.

- Liu, Yun; Cigić, Irena Kralj; Strliča, Matija (2017). "Kinetics of accelerated degradation of historic iron gall ink-containing paper" (PDF). Polymer Degradation and Stability. 142: 255–262. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2017.07.010.

- Christopher Borrelli (30 October 2017). "Newberry Library's 'Book of Magical Charms' is the 'stuff of nightmares'". Chicago Tribune.

- Mazzarino, Sara. "Report on the different inks used in Codex Sinaiticus and assessment of their condition". Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- White, Susan D. (2006). Draw Like Da Vinci. London: Cassell Illustrated, pp.18-19, ISBN 9781844034444.

- "How Is the Torah Made?". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- LIST OF IRON-GALL-BASED FOUNTAIN PEN INKS, compiled by T. Medeiros

- "KWZ Iron Gall inks". Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- "Platinum Classic iron gall inks". Archived from the original on 9 March 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- Platinum Classic Ink - Sepia Black Iron Gall

- LIST OF IRON-GALL-BASED FOUNTAIN PEN INKS, compiled by T. Medeiros

- Registrars' Ink

- Henry 'Inky' Stephens – the inventor of blue-black ink (Stephens Blue-Black Registrar's Ink) at BBC Radio 4

- A Guide for Authorised Persons, HM Passport Office, General Register Office, Issued: 2012, Last Updated: February 2015, Registration stock, 1.18, Page 5

- "Guidebook for The Clergy, HM Passport Office, General Register Office, Issued: 2011, Last Updated: February 2015, Ink, 1.9, Page 7" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- "Dienstordnung für Notarinnen und Notare (DONot), Abschnitt Herstellung der notariellen Urkunden § 29" (in German). Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- Buchheister-Ottersbach: Vorschriften für Drogisten. 11. Auflage von Georg Ottersbach (Volksdorf/Hamburg). Verlag Julius Springer, Berlin 1933 (in German)

- Wailes, Raymond B. (January 1935). "Things to make in your home laboratory". Popular Science Monthly. 126 (1): 54–55.

- "IS 220 (1988): Fountain Pen Ink – Ferro-gallo Tannate (0.1 percent iron content) Third Revision" (PDF). Bureau of Indian Standards. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

External links

- Iron Gall Ink – Traveling Scriptorium – A Teaching Kit by the Yale University Library 21 March 2013

- The Iron Gall Ink Website

- Forty Centuries of Ink by David Carvalho (Project Gutenberg)

- IRON GALLATE INKS-LIQUID AND POWDER by Elmer W. Zimmerman, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS RESEARCH PAPER RP807 Part of Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards, Volume 15, July 1935

| Pens | |

|---|---|

| Types | |

| Parts and tools | |

| Inks | |

| Other | |

| Related | |