Madrasa (/məˈdræsə/, also US: /-rɑːs-/, UK: /ˈmædrɑːsə/; Arabic: مدرسة [mædˈræ.sæ, ˈmad.ra.sa] , pl. مدارس, madāris), sometimes transliterated as madrasah or madrassa, is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whether for elementary education or higher learning. In countries outside the Arab world, the word usually refers to a specific type of religious school or college for the study of the religion of Islam (loosely equivalent to a Christian seminary), though this may not be the only subject studied.

In an architectural and historical context, the term generally refers to a particular kind of institution in the historic Muslim world which primarily taught Islamic law and jurisprudence (fiqh), as well as other subjects on occasion. The origin of this type of institution is widely credited to Nizam al-Mulk, a vizier under the Seljuks in the 11th century, who was responsible for building the first network of official madrasas in Iran, Mesopotamia, and Khorasan. From there, the construction of madrasas spread across much of the Muslim world over the next few centuries, often adopting similar models of architectural design.

The madrasas became the longest serving institutions of the Ottoman Empire, beginning service in 1330 and operating for nearly 600 years on three continents. They trained doctors, engineers, lawyers and religious officials, among other members of the governing and political elite. The madrasas were a specific educational institution, with their own funding and curricula, in contrast with the Enderun palace schools attended by Devshirme pupils.

Definition

Etymology

The word madrasah derives from the triconsonantal Semitic root د-ر-س D-R-S 'to learn, study', using the wazn (morphological form or template) مفعل(ة); mafʻal(ah), meaning "a place where something is done". Thus, madrasah literally means "a place where learning and studying take place" or "place of study". The word is also present as a loanword with the same general meaning in many Arabic-influenced languages, such as: Urdu, Pashto, Baluchi, Persian, Turkish, Azeri, Kurdish, Indonesian, Somali and Bosnian.

Arabic meaning

In the Arabic language, the word مدرسة madrasah simply means the same as school does in the English language, whether that is private, public or parochial school, as well as for any primary or secondary school whether Muslim, non-Muslim, or secular. Unlike the use of the word school in British English, the word madrasah more closely resembles the term school in American English, in that it can refer to a university-level or post-graduate school as well as to a primary or secondary school. For example, in the Ottoman Empire during the Early Modern Period, madrasas had lower schools and specialised schools where the students became known as danişmends. In medieval usage, however, the term madrasah was usually specific to institutions of higher learning, which generally taught Islamic law and occasionally other subjects, as opposed to elementary schools or children's schools, which were usually known as kuttāb, khalwa or maktab. The usual Arabic word for a university, however, is جامعة (jāmiʻah). The Hebrew cognate midrasha also connotes the meaning of a place of learning; the related term midrash literally refers to study or learning, but has acquired mystical and religious connotations.

Meaning and usage in English

In English, the term madrasah or "madrasa" usually refers more narrowly to Islamic institutions of learning. Historians and other scholars also employ the term to refer to historical learning institutions throughout the Muslim world, which is to say a college where Islamic law was taught along with other secondary subjects, but not to secular science schools, modern or historical. These institutions were typically housed in specially designed buildings which were primarily devoted to this purpose. Such institutions are believed to have originated, or at least proliferated, in the region of Iran in the 11th century under vizier Nizam al-Mulk and subsequently spread to other regions of the Islamic world.

History

See also: Nizamiyya and List of oldest madrasahs in continuous operationEarly history

The first institute of madrasa education was at the estate of Zayd ibn Arqam near a hill called Safa, where Muhammad was the teacher and the students were some of his followers. After Hijrah (migration) the madrasa of "Suffa" was established in Madina on the east side of the Al-Masjid an-Nabawi mosque. Ubada ibn as-Samit was appointed there by Muhammad as teacher and among the students. In the curriculum of the madrasa, there were teachings of The Qur'an, The Hadith, fara'iz, tajweed, genealogy, treatises of first aid, etc. There was also training in horse-riding, the art of war, handwriting and calligraphy, athletics and martial arts. The first part of madrasa-based education is estimated from the first day of "nabuwwat" to the first portion of the Umayyad Caliphate. At the beginning of the Caliphate period, the reliance on courts initially confined sponsorship and scholarly activities to major centres.

In the early history of the Islamic period, teaching was generally carried out in mosques rather than in separate specialized institutions. Although some major early mosques like the Great Mosque of Damascus or the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in Cairo had separate rooms which were devoted to teaching, this distinction between "mosque" and "madrasa" was not very present. Notably, the al-Qarawiyyin (Jāmiʻat al-Qarawīyīn), established in 859 in the city of Fes, present-day Morocco, is considered the oldest university in the world by some scholars, though the application of the term "university" to institutions of the medieval Muslim world is disputed. According to tradition, the al-Qarawiyyin mosque was founded by Fāṭimah al-Fihrī, the daughter of a wealthy merchant named Muḥammad al-Fihrī. This was later followed by the Fatimid establishment of al-Azhar Mosque in 969–970 in Cairo, initially as a center to promote Isma'ili teachings, which later became a Sunni institution under Ayyubid rule (today's Al-Azhar University). By the 900s AD, the Madrasa is noted to have become a successful higher education system.

The development of the formal madrasah

In the late 11th century, during the late ʻAbbāsid period, the Seljuk vizier Niẓām al-Mulk created one of the first major official academic institutions known in history as the Madrasah Niẓāmīyah, based on the informal majālis (sessions of the shaykhs). Niẓām al-Mulk, who would later be murdered by the Assassins (Ḥashshāshīn), created a system of state madrasas (in his time they were called the Niẓāmiyyahs, named after him) in various Seljuk and ʻAbbāsid cities at the end of the 11th century, ranging from Mesopotamia to Khorasan. Although madrasa-type institutions appear to have existed in Iran before Nizam al-Mulk, this period is nonetheless considered by many as the starting point for the proliferation of the formal madrasah across the rest of the Muslim world, adapted for use by all four different Sunni Islamic legal schools and Sufi orders. Part of the motivation for this widespread adoption of the madrasah by Sunni rulers and elites was a desire to counter the influence and spread of Shi'ism at the time, by using these institutions to spread Sunni teachings.

Dimitri Gutas and the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy consider the period between the 11th and 14th centuries to be the "Golden Age" of Arabic and Islamic philosophy, initiated by al-Ghazali's successful integration of logic into the madrasah curriculum and the subsequent rise of Avicennism. In addition to religious subjects, they taught the "rational sciences," as varied as mathematics, astronomy, astrology, geography, alchemy and philosophy depending on the curriculum of the specific institution in question. The madrasas, however, were not centres of advanced scientific study; scientific advances in Islam were usually carried out by scholars working under the patronage of royal courts. During the Islamic Golden Age, the territories under the Caliphate experienced a growth in literacy, having the highest literacy rate of the Middle Ages, comparable to classical Athens' literacy in antiquity but on a much larger scale. The emergence of the maktab and madrasa institutions played a fundamental role in the relatively high literacy rates of the medieval Islamic world.

Under the Anatolian Seljuk, Zengid, Ayyubid, and Mamluk dynasties (11th-16th centuries) in the Middle East, many of the ruling elite founded madrasas through a religious endowment and charitable trust known as a waqf. The first documented madrasa created in Syria was the Madrasa of Kumushtakin, added to a mosque in Bosra in 1136. One of the earliest madrasas in Damascus, and one of the first madrasas to be accompanied by the tomb of its founder, is the Madrasa al-Nuriyya (or Madrasa al-Kubra) founded by Nur al-Din Zengi in 1167–1172. After Salah ad-Din (Saladin) overthrew the Shi'a Fatimids in Egypt in 1171, he founded a Sunni madrasa near the tomb of al-Shafi'i in Cairo in 1176–1177, introducing this institution to Egypt. The Mamluks who succeeded the Ayyubids built many more madrasas across their territories. Not only was the madrasa a potent symbol of status for its patrons but it could also be an effective means of transmitting wealth and status to their descendants. Especially during the Mamluk period, when only former slaves (mamālīk) could assume power, the sons of the ruling Mamluk elites were unable to inherit. Guaranteed positions within the new madrasas (and other similar foundations) thus allowed them to maintain some status and means of living even after their fathers' deaths. Madrasas built in this period were often associated with the mausoleums of their founders.

Further west, the Hafsid dynasty introduced the first madrasas to Ifriqiya, beginning with the Madrasa al-Shamma῾iyya built in Tunis in 1238 (or in 1249 according to some sources). By the late 13th century, the first madrasas were being built in Morocco under the Marinid dynasty, starting with the Saffarin Madrasa in Fes (founded in 1271) and culminating with much larger and more ornate constructions like the Bou Inania Madrasa (founded in 1350).

During the Ottoman period the medrese (Turkish word for madrasah) was a common institution as well, often part of a larger külliye or a waqf-based religious foundation which included other elements like a mosque and a hammam (public bathhouse). The following excerpt provides a brief synopsis of the historical origins and starting points for the teachings that took place in the Ottoman madrasas in the Early Modern Period:

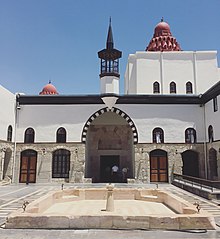

Taşköprülüzâde's concept of knowledge and his division of the sciences provides a starting point for a study of learning and medrese education in the Ottoman Empire. Taşköprülüzâde recognises four stages of knowledge—spiritual, intellectual, oral and written. Thus all the sciences fall into one of these seven categories: calligraphic sciences, oral sciences, intellectual sciences, spiritual sciences, theoretical rational sciences, and practical rational sciences. The first Ottoman medrese was created in İznik in 1331, when a converted Church building was assigned as a medrese to a famous scholar, Dâvûd of Kayseri. Suleyman made an important change in the hierarchy of Ottoman medreses. He established four general medreses and two more for specialised studies, one devoted to the ḥadīth and the other to medicine. He gave the highest ranking to these and thus established the hierarchy of the medreses which was to continue until the end of the empire.

Islamic education in the madrasa

The term "Islamic education" means education in the light of Islam itself, which is rooted in the teachings of the Qur'an - the holy book of the Muslims. Islamic education and Muslim education are not the same. Because Islamic education has epistemological integration which is founded on Tawhid - Oneness or monotheism. To Islam, the Quran is the core of all learning, it is described in this journal as the “Spine of all discipline”

A typical Islamic school usually offers two courses of study: a ḥifẓ course teaching memorization of the Qur'an (the person who commits the entire Qur'an to memory is called a ḥāfiẓ); and an ʻālim course leading the candidate to become an accepted scholar in the community. A regular curriculum includes courses in Arabic, tafsir (Qur'anic interpretation), sharīʻah (Islamic law), hadith, mantiq (logic), and Muslim history. In the Ottoman Empire, during the Early Modern Period, the study of hadiths was introduced by Süleyman I. Depending on the educational demands, some madrasas also offer additional advanced courses in Arabic literature, English and other foreign languages, as well as science and world history. Ottoman madrasas along with religious teachings also taught "styles of writing, grammar, syntax, poetry, composition, natural sciences, political sciences, and etiquette."

People of all ages attend, and many often move on to becoming imams. The certificate of an ʻālim, for example, requires approximately twelve years of study. A good number of the ḥuffāẓ (plural of ḥāfiẓ) are the product of the madrasas. The madrasas also resemble colleges, where people take evening classes and reside in dormitories. An important function of the madrasas is to admit orphans and poor children in order to provide them with education and training. Madrasas may enroll female students; however, they study separately from the men.

Education in historical madrasas

See also: Education in IslamElementary education

Main article: Kuttab

In the medieval Islamic world, an elementary school (for children or for those learning to read) was known as a 'kuttāb' or maktab. Their exact origin is uncertain, but they appear to have been already widespread in the early Abbasid period (8th-9th centuries) and may have played an early role in socializing new ethnic and demographic groups into the Islamic religion during the first few centuries after the Arab-Muslim conquests of the region. Like madrasas (which referred to higher education), a maktab was often attached to an endowed mosque. In the 11th century, the famous Persian Islamic philosopher and teacher Ibn Sīnā (known as Avicenna in the West), in one of his books, wrote a chapter about the maktab entitled "The Role of the Teacher in the Training and Upbringing of Children", as a guide to teachers working at maktab schools. He wrote that children can learn better if taught in classes instead of individual tuition from private tutors, and he gave a number of reasons for why this is the case, citing the value of competition and emulation among pupils, as well as the usefulness of group discussions and debates. Ibn Sīnā described the curriculum of a maktab school in some detail, describing the curricula for two stages of education in a maktab school.

Primary education

Ibn Sīnā wrote that children should be sent to a maktab school from the age of 6 and be taught primary education until they reach the age of 14. During which time, he wrote, they should be taught the Qur'an, Islamic metaphysics, Arabic, literature, Islamic ethics, and manual skills (which could refer to a variety of practical skills).

Secondary education

Ibn Sīnā refers to the secondary education stage of maktab schooling as a period of specialisation when pupils should begin to acquire manual skills, regardless of their social status. He writes that children after the age of 14 should be allowed to choose and specialise in subjects they have an interest in, whether it was reading, manual skills, literature, preaching, medicine, geometry, trade and commerce, craftsmanship, or any other subject or profession they would be interested in pursuing for a future career. He wrote that this was a transitional stage and that there needs to be flexibility regarding the age in which pupils graduate, as the student's emotional development and chosen subjects need to be taken into account.

Higher education

See also: Ijazah

During its formative period, the term madrasah referred to a higher education institution, whose curriculum initially included only the "religious sciences", whilst philosophy and the secular sciences were often excluded. The curriculum slowly began to diversify, with many later madrasas teaching both the religious and the "secular sciences", such as logic, mathematics and philosophy. Some madrasas further extended their curriculum to history, politics, ethics, music, metaphysics, medicine, astronomy and chemistry. The curriculum of a madrasah was usually set by its founder, but most generally taught both the religious sciences and the physical sciences. Madrasas were established throughout the Islamic world, examples being the ninth century University of al-Qarawiyyin, the tenth century al-Azhar University (the most famous), the eleventh century Niẓāmīyah, as well as 75 madrasas in Cairo, 51 in Damascus and up to 44 in Aleppo between 1155 and 1260. Institutions of learning were established in the Andalusian cities of Córdoba, Seville, Toledo, Granada, Murcia, Almería, Valencia and Cádiz during the Caliphate of Córdoba.

In the Ottoman Empire during the early modern period, "Madaris were divided into lower and specialised levels, which reveals that there was a sense of elevation in school. Students who studied in the specialised schools after completing courses in the lower levels became known as danişmends."

Mosques were more than a place of worship as they were also utilized as an area to host community transactions of business. It was the center of most of a city's social and cultural life. Along with this came trades of information and teachings. As the mosque was a starting ground for religious discourse in the Islamic world, these madrasas became more common. In this context, a madrasa would be referred to as a localized area or center within the mosque for studies and teachings relating the Quran. Among the first advanced topics featured at a madrasa was Islamic law. There was a premium fee required to study Islamic law, which was sometimes fronted by state or private subsidiaries. The topics of this higher education also expanded larger than the Islamic time and area. Arab translations of Greco-Roman classical texts were often examined for mathematical and grammatical discourse. Since the focus of theology and legal study was utmost, specified law schools began their own development. On the theological side however, these remained mainly at the general madrasa since it was more common and easier for the lower-level students to approach. The requirement of competent teachers to keep a madrasa up and running was also important. It was not uncommon for these scholars to be involved in multiple fields such as Abd al-Latif who was an expert in medicine, grammar, linguistics, law, alchemy, and philosophy. The choice of freedom in inquiry was also important. Muslim higher education at madrasas offered not only mastery in specified fields but also a more generalized, broader option.

In Muslim India, the madrasa started off as providing higher education similarly to other parts of the Islamic world. The primary function for these institutions was to train and prepare workers for bureaucratic work as well as the judicial system. The curriculum generally consisted of logic, philosophy, law, history, politics, and particularly religious sciences, later incorporating more of mathematics, astronomy, geography, and medicine. Madrasas were often subsidized and founded by states or private individuals, and well-qualified teachers filled in the role for professors. Foundations of Islamic higher education in India is tied to the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in 1206 which set a basis of importance for Muslim education. Under control of the Delhi Sultanate, two early important madrasas were founded. The first was the Mu’zziyya named after Muḥammad Ghuri of the Ghorid Dynasty and his title of Muʿizz al-Dīn and founded by Sultan Iltutmish. The other madrasa was the Nāṣiriyya, named after Nāṣir al-Dīn Maḥmūd and built by Balban. These two madrasas bear importance as a starting point for higher education for Muslim India. Babur of the Mughal Empire founded a madrasa in Delhi which he specifically included the subjects of mathematics, astronomy, and geography besides the standard subjects of law, history, secular and religious sciences. Although little is known about the management and inner workings of these places of Islamic higher education, religious studies bore the focus amongst most other subjects, particularly the rational sciences such as mathematics, logic, medicine, and astronomy. Although some tried to emphasize these subjects more, it is doubtful that every madrasa made this effort.

While "madrasah" can now refer to any type of school, the term madrasah was originally used to refer more specifically to a medieval Islamic centre of learning, mainly teaching Islamic law and theology, usually affiliated with a mosque, and funded by an early charitable trust known as waqf.

Law school

See also: Sharia and FiqhMadrasas were largely centred on the study of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence). The ijāzat al-tadrīs wa-al-iftāʼ ("licence to teach and issue legal opinions") in the medieval Islamic legal education system had its origins in the ninth century after the formation of the madhāhib (schools of jurisprudence). George Makdisi considers the ijāzah to be the origin of the European doctorate. However, in an earlier article, he considered the ijāzah to be of "fundamental difference" to the medieval doctorate, since the former was awarded by an individual teacher-scholar not obliged to follow any formal criteria, whereas the latter was conferred on the student by the collective authority of the faculty. To obtain an ijāzah, a student "had to study in a guild school of law, usually four years for the basic undergraduate course" and ten or more years for a post-graduate course. The "doctorate was obtained after an oral examination to determine the originality of the candidate's theses", and to test the student's "ability to defend them against all objections, in disputations set up for the purpose." These were scholarly exercises practised throughout the student's "career as a graduate student of law." After students completed their post-graduate education, they were awarded ijazas giving them the status of faqīh 'scholar of jurisprudence', muftī 'scholar competent in issuing fatwās', and mudarris 'teacher'.

The Arabic term ijāzat al-tadrīs was awarded to Islamic scholars who were qualified to teach. According to Makdisi, the Latin title licentia docendi 'licence to teach' in the European university may have been a translation of the Arabic, but the underlying concept was very different. A significant difference between the ijāzat al-tadrīs and the licentia docendi was that the former was awarded by the individual scholar-teacher, while the latter was awarded by the chief official of the university, who represented the collective faculty, rather than the individual scholar-teacher.

Much of the study in the madrasah college centred on examining whether certain opinions of law were orthodox. This scholarly process of "determining orthodoxy began with a question which the Muslim layman, called in that capacity mustaftī, presented to a jurisconsult, called mufti, soliciting from him a response, called fatwa, a legal opinion (the religious law of Islam covers civil as well as religious matters). The mufti (professor of legal opinions) took this question, studied it, researched it intensively in the sacred scriptures, in order to find a solution to it. This process of scholarly research was called ijtihād, literally, the exertion of one's efforts to the utmost limit."

Medical school

See also: BimaristanThough Islamic medicine was most often taught at the bimaristan teaching hospitals, there were also several medical madrasas dedicated to the teaching of medicine. For example, of the 155 madrasa colleges in 15th century Damascus, three of them were medical schools.

Toby Huff argues that no medical degrees were granted to students, as there was no faculty that could issue them, and that therefore, no system of examination and certification developed in the Islamic tradition like that of medieval Europe. However, the historians Andrew C. Miller, Nigel J. Shanks and Dawshe Al-Kalai point out that, during this era, physician licensure became mandatory in the Abbasid Caliphate. In 931 AD, Caliph Al-Muqtadir learned of the death of one of his subjects as a result of a physician's error. He immediately ordered his muhtasib Sinan ibn Thabit to examine and prevent doctors from practicing until they passed an examination. From this time on, licensing exams were required and only qualified physicians were allowed to practice medicine. The study of Medicine and many other sciences that took place in Madrasas made large contributions to western societies in later years.

In the Early Modern Period in the Ottoman Empire, "Suleyman I added new curriculums to the Ottoman medreses of which one was medicine, which alongside studying of the ḥadīth was given highest rank."

Madrasa and university

- Note: The word jāmiʻah (Arabic: جامعة) simply means 'university'. For more information, see Islamic university (disambiguation).

Scholars like Arnold H. Green and Seyyed Hossein Nasr have argued that, starting in the tenth century, some medieval Islamic madrasas indeed became universities. However, scholars like George Makdisi, Toby Huff and Norman Daniel argue that the European medieval university has no parallel in the medieval Islamic world. Darleen Pryds questions this view, pointing out that madrasas and European universities in the Mediterranean region shared similar foundations by princely patrons and were intended to provide loyal administrators to further the rulers' agenda. Some other scholars regard the university as uniquely European in origin and characteristics.

Al-Qarawīyīn University in Fez, present-day Morocco is recognised by many historians as the oldest degree-granting university in the world, having been founded in 859 as a mosque by Fatima al-Fihri. While the madrasa college could also issue degrees at all levels, the jāmiʻahs (such as al-Qarawīyīn and al-Azhar University) differed in the sense that they were larger institutions, more universal in terms of their complete source of studies, had individual faculties for different subjects, and could house a number of mosques, madrasas, and other institutions within them. Such an institution has thus been described as an "Islamic university".

Al-Azhar University, founded in Cairo, Egypt in 975 by the Ismaʻīlī Shīʻī Fatimid dynasty as a jāmiʻah, had individual faculties for a theological seminary, Islamic law and jurisprudence, Arabic grammar, Islamic astronomy, early Islamic philosophy and logic in Islamic philosophy. In the second half of the 19th century in Egypt, Muslim Egyptians began to attend secular schools, and a movement arose in the late 19th to the early 20th century to modernize al-Azhar. The postgraduate doctorate in law was only obtained after "an oral examination to determine the originality of the candidate's theses", and to test the student's "ability to defend them against all objections, in disputations set up for the purpose." ‘Abd al-Laṭīf al-Baghdādī also delivered lectures on Islamic medicine at al-Azhar, while Maimonides delivered lectures on medicine and astronomy there during the time of Saladin. Another early jāmiʻah was the Niẓāmīyah of Baghdād (founded 1091), which has been called the "largest university of the Medieval world." Mustansiriya University, established by the ʻAbbāsid caliph al-Mustanṣir in 1227, in addition to teaching the religious subjects, offered courses dealing with philosophy, mathematics and the natural sciences. Madrasas by the 11th century had buildings and full time working educators. These educators were provided with places to live inside the madrasas. The institutions by this time occumulated a wide spread of attendance among the population. The attraction of the educational institution was that it provided free education for everyone in attendance. Furthermore, sciences at madrasas were indeed taught, and much of the material was from well-known scholars of the sciences such as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, who was the “most famous and most successful” editor of the Shi’i law, kalam philosophy which include mathematic works and astrology.

However, the classification of madrasas as "universities" is disputed on the question of understanding of each institution on its own terms. In madrasas, the ijāzahs were only issued in one field, the Islamic religious law of sharīʻah, and in no other field of learning. Other academic subjects, including the natural sciences, philosophy and literary studies, were only treated "ancillary" to the study of the Sharia. For example, at least in Sunni madrasas, astronomy was only studied (if at all) to supply religious needs, like the time for prayer. This is why Ptolemaic astronomy was considered adequate, and is still taught in some modern day madrasas. The Islamic law undergraduate degree from al-Azhar, the most prestigious madrasa, was traditionally granted without final examinations, but on the basis of the students' attentive attendance to courses. In contrast to the medieval doctorate which was granted by the collective authority of the faculty, the Islamic degree was not granted by the teacher to the pupil based on any formal criteria, but remained a "personal matter, the sole prerogative of the person bestowing it; no one could force him to give one".

Although there is a sort of validity to what was just mentioned in this section, more specifically in the previous paragraph, other sources also convey that an emphasis on the teaching of sciences in madrasas, and the licensing of ijāzahs to those who proved satisfactory in the knowledge of their specific scientific field of study, were indeed conducted. It is historically inaccurate to definitively mention that all forms of science were studied solely for the advancement/supplication of religious needs. This can be evident when one further examines the specific fields of secular sciences that have achieved an established position in madrasa curriculum. Such fields included the sciences of mathematics, medicine and pharmacology, natural philosophy, divination, magic, and alchemy (The last three being clumped up into one set of coursework). To support the claims mentioned earlier in this section, it has been noted that ijāzahs are not issued to these sciences as much as they are to religious studies, yet at the same time, there is no evidence fully supporting that none were given to these subjects. Clear examples of the issuing of such ijāzahs can be seen in numerous manuscripts, or more specifically, in Shams al-Din al-Sakhawi's multiple collections of manuscript titles and biographies. Further evidence of this was illustrated by al-Sakhawi. He mentioned that in places like Syria and Egypt, it has been suggested that public performances of knowledge, which its conduction was required for one to finally receive their ijāzah, included mathematics in its content. There are plenty of other examples of the issuance of ijazahs for scientific subjects. Ali b. Muhammad al-Qalasadi, a prominent mathematician in his day, was mentioned to be responsible for giving his students an ijāzah to teach his mathematical treatise on the dust letters. Ibn al-Nafis gave an ijazah to his student al-Quff for proving sufficient in knowledge of his commentary on the medical book, On the Nature of Man. In addition, a copy of a commentary on Hunayn b. Ishaq's, Problems of Medicine for Students, managed to show that one of its readers had sufficient knowledge in the medical text, Synopses of the Alexandrians. Later on in this commentary, an ijazah, issued by a physician from Damascus, was present to confirm that one was indeed issued here for said student. Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi was a student of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi who was considered to be a proficient polymath, astronomer, philosopher, and physician who issued an ijazah to Najm al-Milla wa-l-Din M. b. M. b. Abi Bakr al-Tabrizi. This license was very extensive, allowing him to teach religious, philosophical, and even medical texts like Ibn Sina's first book in his Canon of Medicine. These are just a few select/historical examples of the issuance of ijazahs for scientific subjects, thereby proving that such licenses were indeed issued along with those regarding religious studies. There are many more examples of this that are not listed on this page, but can easily be found. When taking this evidence into account, one may then reasonably assume that the presence, teaching, and licensing of certain sciences in madrasas has been historically underrepresented. This information, along with some of what is discussed in the following sections/paragraphs on this page, may now hopefully help one in identifying whether or not madrasas can indeed be classified as "Universities". However, arguments for why they should not be classified as such will later be proposed as well.

Medievalist specialists who define the university as a legally autonomous corporation disagree with the term "university" for the Islamic madrasas and jāmi‘ahs because the medieval university (from Latin universitas) was structurally different, being a legally autonomous corporation rather than a waqf institution like the madrasa and jāmiʻah. Despite the many similarities, medieval specialists have coined the term "Islamic college" for madrasa and jāmiʻah to differentiate them from the legally autonomous corporations that the medieval European universities were. In a sense, the madrasa resembles a university college in that it has most of the features of a university, but lacks the corporate element. Toby Huff summarises the difference as follows:

From a structural and legal point of view, the madrasa and the university were contrasting types. Whereas the madrasa was a pious endowment under the law of religious and charitable foundations (waqf), the universities of Europe were legally autonomous corporate entities that had many legal rights and privileges. These included the capacity to make their own internal rules and regulations, the right to buy and sell property, to have legal representation in various forums, to make contracts, to sue and be sued."

As Muslim institutions of higher learning, the madrasa had the legal designation of waqf. In central and eastern Islamic lands, the view that the madrasa, as a charitable endowment, will remain under the control of the donor (and their descendant), resulted in a "spurt" of establishment of madrasas in the 11th and 12th centuries. However, in Western Islamic lands, where the Maliki views prohibited donors from controlling their endowment, madrasas were not as popular. Unlike the corporate designation of Western institutions of higher learning, the waqf designation seemed to have led to the exclusion of non-orthodox religious subjects such a philosophy and natural science from the curricula. The madrasa of al-Qarawīyīn, one of the two surviving madrasas that predate the founding of the earliest medieval universities and are thus claimed to be the "first universities" by some authors, has acquired official university status as late as 1947. The other, al-Azhar, did acquire this status in name and essence only in the course of numerous reforms during the 19th and 20th century, notably the one of 1961 which introduced non-religious subjects to its curriculum, such as economics, engineering, medicine, and agriculture. Many medieval universities were run for centuries as Christian cathedral schools or monastic schools prior to their formal establishment as universitas scholarium; evidence of these immediate forerunners of the university dates back to the sixth century AD, thus well preceding the earliest madrasas. George Makdisi, who has published most extensively on the topic concludes in his comparison between the two institutions:

Thus the university, as a form of social organization, was peculiar to medieval Europe. Later, it was exported to all parts of the world, including the Muslim East; and it has remained with us down to the present day. But back in the middle ages, outside of Europe, there was nothing anything quite like it anywhere.

Nevertheless, Makdisi has asserted that the European university borrowed many of its features from the Islamic madrasa, including the concepts of a degree and doctorate. Makdisi and Hugh Goddard have also highlighted other terms and concepts now used in modern universities which most likely have Islamic origins, including "the fact that we still talk of professors holding the 'chairman' of their subject" being based on the "traditional Islamic pattern of teaching where the professor sits on a chair and the students sit around him", the term 'academic circles' being derived from the way in which Islamic students "sat in a circle around their professor", and terms such as "having 'fellows', 'reading' a subject, and obtaining 'degrees', can all be traced back" to the Islamic concepts of aṣḥāb ('companions, as of Muhammad'), qirāʼah ('reading aloud the Qur'an') and ijāzah ('licence ') respectively. Makdisi has listed eighteen such parallels in terminology which can be traced back to their roots in Islamic education. Some of the practices now common in modern universities which Makdisi and Goddard trace back to an Islamic root include "practices such as delivering inaugural lectures, wearing academic robes, obtaining doctorates by defending a thesis, and even the idea of academic freedom are also modelled on Islamic custom." The Islamic scholarly system of fatwá and ijmāʻ, meaning opinion and consensus respectively, formed the basis of the "scholarly system the West has practised in university scholarship from the Middle Ages down to the present day." According to Makdisi and Goddard, "the idea of academic freedom" in universities was also "modelled on Islamic custom" as practised in the medieval Madrasa system from the ninth century. Islamic influence was "certainly discernible in the foundation of the first deliberately planned university" in Europe, the University of Naples Federico II founded by Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor in 1224.

However, all of these facets of medieval university life are considered by other scholars to be independent medieval European developments with no necessary Islamic influence. Norman Daniel criticizes Makdisi for overstating his case by simply resting on "the accumulation of close parallels" while failing to point to convincing channels of transmission between the Muslim and Christian world. Daniel also points out that the Arab equivalent of the Latin disputation, the taliqa, was reserved for the ruler's court, not the madrasa, and that the actual differences between Islamic fiqh and medieval European civil law were profound. The taliqa only reached Islamic Spain, the only likely point of transmission, after the establishment of the first medieval universities. Moroever, there is no Latin translation of the taliqa and, most importantly, no evidence of Latin scholars ever showing awareness of Arab influence on the Latin method of disputation, something they would have certainly found noteworthy. Rather, it was the medieval reception of the Greek Organon which set the scholastic sic et non in motion. Daniel concludes that resemblances in method had more to with the two religions having "common problems: to reconcile the conflicting statements of their own authorities, and to safeguard the data of revelation from the impact of Greek philosophy"; thus Christian scholasticism and similar Arab concepts should be viewed in terms of a parallel occurrence, not of the transmission of ideas from one to the other, a view shared by Hugh Kennedy. Toby Huff, in a discussion of Makdisi's hypothesis, argues:

It remains the case that no equivalent of the bachelor's degree, the licentia docendi, or higher degrees ever emerged in the medieval or early modern Islamic madrasas.

George Saliba criticized Huff's views regarding the legal autonomy of European universities and limited curriculum of Madrasahs, demonstrating that there were many Madrasahs dedicated to the teaching of non-religious subjects and arguing that Madrasahs generally had greater legal autonomy than medieval European universities. According to Saliba, Madrasahs "were fully protected from interference in their curriculum by the very endowments that established them in the first place." Examples include the Dakhwariyya madrasah in Damascus, which was dedicated to medicine, a subject also taught at Islamic hospitals; the Madrasah established by Kamal al-Din Ibn Man`a (d. 1242) in Mosul which taught astronomy, music, and the Old the New Testaments; Ulugh Beg's Madrasah in Samarqand which taught astronomy; and Shi`i madrasahs in Iran which taught astronomy along with religious studies. According to Saliba:

As I noted in my original article, students in the medieval Islamic world, who had the full freedom to chose their teacher and the subjects that they would study together, could not have been worse off than today’s students, who are required to pursue a specific curriculum that is usually designed to promote the ideas of their elders and preserve tradition, rather than introduce them to innovative ideas that challenge ‘received texts.’ Moreover, if Professor Huff had looked more carefully at the European institutions that produced science, he would have found that they were mainly academies and royal courts protected by individual potentates and not the universities that he wishes to promote. But neither universities nor courts were beyond the reach of the Inquisition, which is another point that he seems to neglect.

Female education

See also: Women in Islam, Women's literary salons and societies in the Arab world, and List of female Muslim scholarsPrior to the 12th century, women accounted for less than one percent of the world's Islamic scholars. However, al-Sakhawi and Mohammad Akram Nadwi have since found evidence of over 8,000 female scholars since the 15th century. al-Sakhawi devotes an entire volume of his 12-volume biographical dictionary al-Ḍawʾ al-lāmiʻ to female scholars, giving information on 1,075 of them. More recently, the scholar Mohammad Akram Nadwi, currently a researcher from the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, has written 40 volumes on the muḥaddithāt (the women scholars of hadith), and found at least 8,000 of them.

From around 750, during the Abbasid Caliphate, women "became renowned for their brains as well as their beauty". In particular, many well known women of the time were trained from childhood in music, dancing and poetry. Mahbuba was one of these. Another female (albeit probably fictional) figure to be remembered for her achievements was Tawaddud, "a slave girl who was said to have been bought at great cost by Hārūn al-Rashīd because she had passed her examinations by the most eminent scholars in astronomy, medicine, law, philosophy, music, history, Arabic grammar, literature, theology and chess". Moreover, among the most prominent feminine figures was Shuhda who was known as "the Scholar" or "the Pride of Women" during the 12th century in Baghdad. Despite the recognition of women's aptitudes during the Abbasid dynasty, all these came to an end in Iraq with the sack of Baghdad in 1258.

According to the Sunni scholar Ibn ʻAsākir in the 12th century, there were opportunities for female education in the medieval Islamic world, writing that women could study, earn ijazahs (academic degrees), and qualify as scholars and teachers. This was especially the case for learned and scholarly families, who wanted to ensure the highest possible education for both their sons and daughters. Ibn ʻAsakir had himself studied under 80 different female teachers in his time. Female education in the Islamic world was inspired by Muhammad's wives, such as Khadijah, a successful businesswoman, and 'A'isha, a strong leader and interpreter of the Prophet's actions. According to a hadith attributed both to Muhammad and 'A'isha, the women of Medina were praiseworthy because of their desire for religious knowledge: Although female madrasas did exist before the 1970s large strides were made is regards to female education. After the 1970s a large increase in total female madrasas took place expanded very rapidly across the region.

How splendid were the women of the ansar; shame did not prevent them from becoming learned in the faith.

While it was not common for women to enroll as students in formal classes, it was common for women to attend informal lectures and study sessions at mosques, madrasas and other public places. While there were no legal restrictions on female education, some men did not approve of this practice, such as Muhammad ibn al-Hajj (d. 1336) who was appalled at the behaviour of some women who informally audited lectures in his time:

what some women do when people gather with a shaykh to hear books. At that point women come, too, to hear the readings; the men sit in one place, the women facing them. It even happens at such times that some of the women are carried away by the situation; one will stand up, and sit down, and shout in a loud voice. her awra will appear; in her house, their exposure would be forbidden — how can it be allowed in a mosque, in the presence of men?

The term ʻawrah is often translated as 'that which is indecent', which usually meant the exposure of anything other than a woman's face and hands, although scholarly interpretations of the ʻawrah and ḥijāb have always tended to vary, with some more or less strict than others.

Women played an important role in the foundations of many Islamic educational institutions, such as Fatima al-Fihri's founding of the al-Qarawiyyin mosque in 859, which later developed into a madrasa. The role of female patrons was also evident during the Ayyubid dynasty in the 12th and 13th centuries, when 160 mosques and madrasas were established in Damascus, 26 of which were funded by women through the waqf (charitable trust) system. Half of all the royal patrons for these institutions were also women. Royal women were also major patrons of culture and architecture in the Ottoman Empire, founding many külliyes (religious and charitable complexes) that included madrasas.

In the 20th century in Indonesia, madrasas founded by women played an important role in increasing educational standards in the country. In November 1923, Rahmah el Yunusiyah opened a school located in Padang Panjang called Diniyah School Putri or Madrasah Diniyah Li al-Banat. This school is generally thought to be the first Muslim religious school in the country for young girls. El Yunusiyah, a deeply religious woman, believed that Islam demanded a central role for women and women's education. The school gained considerable popularity and by the end of the 1930s had as many as five hundred students. The scholar Audrey Kahin calls Diniyah Putri "one of the most successful and influential of the schools for women" in pre-independence Indonesia.

While madrasas continue to play a pivotal role in the education of many, including young girls, there are still some cultural norms that find their way into the hallways and classrooms of these institutions. In article from 2021, Hem Borker, a professor at Jamia Millia Islamia, had the opportunity to travel to India and see the daily life of girls at a residential madrasa. In these madrasas in Northern India, young girls have the ability to receive an education, however, many of the practices within these institutions can be seen as very restrictive or at least by Western standards. Many madrasas that enroll girls act as "purdah institutions." In Persian, purdah translates to curtain or cover. With respect to these madrasas in Northern India, a purdah institution is an institution in which there are several guidelines female students must adhere to as a way to cover themselves both physically and culturally, These restrictions are based on the students' gender and create a segregation of sorts. Girls are expected to wear veils over their faces and cover their entire bodies as a means of dressing modestly by cultural standards. In addition to the clothes that these girls wear, the physical building itself also adheres to the ideals of a purdah institution. Classrooms and hallways are separated by gender in order to prevent fraternization. Within many of these madrasas, even the windows are lined with metal grills in order to prevent students from looking to the outside as well as to prevent people on the outside to look inward. In addition to the physical layout of the building, there are a series of rules female students must adhere to. Some of these rules include girls must lower their head and their voice when addressing their male counterparts. As they pass windows, even with barriers blocking most of their view to the outside and blocking the view of those on the outside, they are expected to lower their gaze. Going back to the idea of clothing, they must wear a niqāb in order to go outside. Within a cultural context, these rules are very appropriate. In addition to teaching specific subject academic content, institutions such as these purdah madrasas are also incorporating appropriate cultural and societal behavior outside the walls of the building.

Architecture

See also: Islamic architectureArchitectural origins

Madrasas were generally centered around an interior courtyard and the classical madrasa form generally featured four iwans (vaulted chambers open on one side) arranged symmetrically around the courtyard. The origin of this architectural model may have been Buddhist monasteries in Transoxiana (Central Asia), of which some early surviving remains demonstrate this type of layout. Another possible origin may have been domestic houses in the region of Khorasan. Practically none of the first madrasas founded under Nizam al-Mulk (Seljuk vizier between 1064 and 1092) have survived, though partial remains of one madrasa in Khargerd, Iran, include an iwan and an inscription attributing it to Nizam al-Mulk. Nonetheless, it is clear that the Seljuks constructed many madrasas across their empire within a relatively short period of time, thus spreading both the idea of this institution and the architectural models on which later examples were based.

Evolution and spread across different regions

Seljuk Anatolia

In contrast to early Iranian Seljuk madrasas, a large number of madrasas from the Anatolian Seljuk Empire (between 1077 and 1308) have survived, and are the closest examples we have of Iranian-influenced early madrasa architecture. However, though each usually included a large central courtyard, their overall layouts were more variable and may have reflected more multi-purpose functions, often with an attached mausoleum, a minaret, and an ornate entrance portal. The courtyards were sometimes covered by a large dome (as with the Karatay Madrasa, founded in 1279, and other madrasas in Konya), reflecting an ongoing transition to domed Islamic buildings in Anatolia and later Ottoman architecture.

Syria and Egypt

In Syria and the surrounding region, the earliest madrasas were often relatively small buildings, the earliest example of which is one in Bosra founded in 1136–37. Madrasa architecture in this region appears to have evolved out of Seljuk prototypes. Another early important example is the Madrasa of Nur al-Din from 1167. Under the Ayyubid dynasty madrasas began to take on added importance, with the first madrasa in Egypt (no longer extant) being built by Salah ad-Din (Saladin) in 1180 next to the Mausoleum of Imam al-Shafi'i in Cairo's Qarafa Cemetery. As with the earlier Seljuk madrasas, it is likely that these foundations were motivated by a desire to counteract the influence of Isma'ili proselytism and propaganda during the Fatimid Caliphate. Among the surviving Ayyubid madrasas in Egypt are the remains of the Madrasa of al-Kamil (founded by Sultan al-Kamil Ayyub in 1229) and the more important Madrasa al-Salihiyya founded by Sultan al-Salih Ayyub founded in 1242, to which was later attached al-Salih's mausoleum. In Syria, an exceptional example of a monumental madrasa from this period is the al-Firdaws Madrasa in Aleppo. Many more examples from this period, however, have not survived.

After the faltering of the Ayyubid dynasty and the transition to the Mamluk Sultanate around 1250, the Mamluks became eager patrons of architecture. Many of their projects involved the construction of madrasas as part of larger multi-functional religious complexes, usually attached to their personal mausoleums, which provided services to the general population while also promoting their own prestige and pious reputations. In Egyptian Mamluk architecture, which largely used stone, the madrasa layout generally had two prominent iwans which were aligned to the qibla and faced each other across a central courtyard, while two "lateral" iwans faced each across each on the other two sides of the courtyard. Prominent examples of these include the madrasa of the Sultan Qalawun complex (built in 1284–1285) and the neighbouring complex of his son al-Nasir Muhammad (finished in 1304). One exceptional madrasa, which also served as a mosque and was easily one of the most massive structures of its time, was the monumental Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Hasan (built from 1356 to 1363), with a large central courtyard surrounded by four enormous iwans. While the unique Madrasa of Sultan Hasan provided instruction in all four Sunni legal schools of thought, most madrasas and mosques in Egypt followed the Shafi'i school. Moreover, due to the already dense urban fabric of Cairo, Mamluk architectural complexes adopted increasingly irregular and creatively designed floor plans to compensate for limited space while simultaneously attempting to maximize their prominence and visibility from the street.

While Mamluk architecture outside Cairo was generally of lesser quality and craftsmanship, there were nonetheless many examples. The Madrasa al-Zahiriyya in Damascus, which contains the mausoleum of Sultan Baybars I, is still essentially Ayyubid in style. The city of Tripoli in Lebanon also holds a concentration of Mamluk-era architecture, including madrasas. However, the most significant Mamluk archtiectural patronage outside of Cairo is likely in Jerusalem, as with the example of the major al-Ashrafiyya Madrasa on the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif), which was rebuilt in its current form by Sultan Qaytbay in the late 15th century.

Cruciform madrasas, which have a four-iwan plan, came to prominence in Egypt. They also appeared in Syria-Palestine, e.g., Jerusalem's Tankiziyya, Arghūniyya, Ṭashtamuriyya, Muzhiriyya, and Damascus's Ẓāhirīyah.

Maghreb (North Africa)

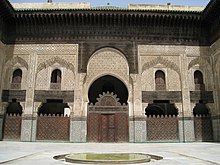

In northwestern Africa (the Maghrib or Maghreb), including Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, madrasas began to be constructed in the 13th century under the Marinid and Hafsid dynasties. In Tunisia (or Ifriqiya), the earliest Hafsid madrasa was the Madrasa al-Shamma'iyya founded in 1238 (or in 1249 according to some sources). In Morocco, the first madrasa was the Madrasa as-Saffarin built in Fes in 1271, followed by many others constructed around the country. The main architectural highlights among these are the Madrasa as-Sahrij (built in 1321–1328), the Madrasa al-Attarin (built in 1323–1325), and the Madrasa of Salé (completed in 1341), all of which are lavishly decorated with sculpted wood, carved stucco, and zellij mosaic tilework. The Bou Inania Madrasa in Fes, built in 1350–1355, distinguished itself from other madrasas by its size and by being the only madrasa which also officially functioned as a public Friday mosque. The Marinids also built madrasas in Algeria, particularly in Tlemcen.

In Morocco, madrasas were generally built in brick and wood and were still centered around a main internal courtyard with a central fountain or water basin, around which student dorms were distributed across one or two floors. A prayer hall or mosque chamber usually stood opposite the entrance on one side of the courtyard. The Bou Inania Madrasa in Fes also contained two side-chambers opening off the lateral sides of its courtyard, which may reflect an influence of the older four-iwan layout. However, most other Moroccan madrasas did not have this feature and the courtyards were instead flanked by ornate galleries. By contrast with Mamluk structures to the east, Moroccan and Maghrebi madrasas were not prominently distinguishable from the outside except for an ornate entrance portal decorated with carved wood and stucco. This model continued to be found in later madrasas like the Ben Youssef Madrasa of the 16th century in Marrakesh.

Iran, Iraq, and Central Asia

Very few if any formal madrasas from before the Mongol invasions have survived in Iran. One exception is the Mustansiriyya Madrasa in Baghdad, which dates from 1227 and is also the earliest "universal" madrasa, which is to say the first madrasa that taught all four Sunni maddhabs (legal schools of thought). Later, the Mongol Ilkhanid dynasty and the many dynasties that followed them (e.g. the Timurids and Safavids) nonetheless built numerous monumental madrasas, many of which are excellent examples of Iranian Islamic architecture. In some cases, these madrasas were directly attached and integrated into larger mosques, as with those attached to the Shah Mosque in Isfahan (17th century). In other cases they were built as more or less separate entities, such as with the Chahar Bagh Madrasa (also in Isfahan, 17th-18th centuries), or the 15th-century Timurid Ulugh Beg Madrasa and two other monumental 17th-century madrasas at the Registan complex in Samarkand.

The form of the madrasa does not appear to have changed significantly over time in this region. The Timurid period (late 14th and 15th century), however, was a "golden age" of Iranian madrasas, during which the four-iwan model was made much larger and more monumental, on a par with major mosques, thanks to intense patronage from Timur and his successors. Madrasas in the Iranian architectural tradition continued to be centered around a large square or rectangular courtyard with a central water basin and surrounded by a one or two-story arcade. Either two or four large iwans stood at the ends of the central axes of the courtyard.

Ottoman Empire

Ottoman architecture evolved out of its Anatolian Seljuk predecessors into a particular style. In the classical Ottoman period (15th-16th centuries), the typical form of the madrasa had become a large courtyard surrounded by an arched gallery covered by a series of domes, similar to the sahn (courtyard) of imperial mosques. Madrasas were generally limited to a main ground floor, and were often built as auxiliary buildings to a central mosque which anchored a külliye or charitable complex. This marked a certain departure from other madrasa styles as it emphasized the feeling of space for its own sake instead of focusing on the practical function of housing as many students as possible within a small area. This is evident in the külliye complex of Mehmet II Fatih, which included 16 madrasa buildings arranged symmetrically around the Fatih Mosque. The Süleymaniye complex, often considered the apogee of Ottoman architecture, included four madrasas as part of a vast and carefully designed architectural ensemble at the top of one of Istanbul's highest hills.

Madrasas by region

Ottoman Empire

| This section possibly contains original research. It cites sources in support of certain statements and quotes, but these are used as arguments leading to conclusions with no supporting citations. (See also WP:NOTESSAY.) Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (December 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

"The first Ottoman Medrese was created in İznik in 1331 and most Ottoman medreses followed the traditions of Sunni Islam." "When an Ottoman sultan established a new medrese, he would invite scholars from the Islamic world—for example, Murad II brought scholars from Persia, such as ʻAlāʼ al-Dīn and Fakhr al-Dīn who helped enhance the reputation of the Ottoman medrese". This reveals that the Islamic world was interconnected in the early modern period as they travelled around to other Islamic states exchanging knowledge. This sense that the Ottoman Empire was becoming modernised through globalization is also recognised by Hamadeh who says: "Change in the eighteenth century as the beginning of a long and unilinear march toward westernisation reflects the two centuries of reformation in sovereign identity." İnalcık also mentions that while scholars from for example Persia travelled to the Ottomans in order to share their knowledge, Ottomans travelled as well to receive education from scholars of these Islamic lands, such as Egypt, Persia and Turkestan. Hence, this reveals that similar to today's modern world, individuals from the early modern society travelled abroad to receive education and share knowledge and that the world was more interconnected than it seems. Also, it reveals how the system of "schooling" was also similar to today's modern world where students travel abroad to different countries for studies. Examples of Ottoman madrasas are the ones built by Muhammad the Conqueror. He built eight madrasas that were built "on either side of the mosque where there were eight higher madrasas for specialised studies and eight lower medreses, which prepared students for these." The fact that they were built around, or near mosques reveals the religious impulses behind madrasa building and it reveals the interconnectedness between institutions of learning and religion. The students who completed their education in the lower medreses became known as danismends. This reveals that similar to the education system today, the Ottomans' educational system involved different kinds of schools attached to different kinds of levels. For example, there were lower madrasas and specialised ones, and for one to get into the specialised area meant that he had to complete the classes in the lower one in order to adequately prepare himself for higher learning.

This is the rank of madrasas in the Ottoman Empire from the highest ranking to the lowest: (From İnalcık, 167).

- Semniye

- Darulhadis

- Madrasas built by earlier sultans in Bursa.

- Madrasas endowed by great men of state.

Although Ottoman madrasas had a number of different branches of study, such as calligraphic sciences, oral sciences, and intellectual sciences, they primarily served the function of an Islamic centre for spiritual learning. Often mentioned by critics that madrasas did not include a variety of natural sciences during the time of the Ottoman Empire, madrasas included curriculums that included a wide range of natural sciences. There were many well-known Muslim scholars, mathematicians, and scientists that all worked to teach high-ranking families and children of the sciences. it known that "The goal of all knowledge and in particular, of the spiritual sciences is knowledge of God." Religion, for the most part, determines the significance and importance of each science. As İnalcık mentions: "Those which aid religion are good and sciences like astrology are bad." However, even though mathematics, or studies in logic were part of the madrasa's curriculum, they were all primarily concerned with religion. Even mathematics had a religious impulse behind its teachings. "The Ulema of the Ottoman medreses held the view that hostility to logic and mathematics was futile since these accustomed the mind to correct thinking and thus helped to reveal divine truths" – key word being "divine". İnalcık also mentions that even philosophy was only allowed to be studied so that it helped to confirm the doctrines of Islam." Hence, madrasas – schools were basically religious centres for religious teachings and learning in the Ottoman world. Although scholars such as Goffman have argued that the Ottomans were highly tolerant and lived in a pluralistic society, it seems that schools that were the main centres for learning were in fact heavily religious and were not religiously pluralistic, but rather Islamic in nature. Similarly, in Europe "Jewish children learned the Hebrew letters and texts of basic prayers at home, and then attended a school organised by the synagogue to study the Torah." Wiesner-Hanks also says that Protestants also wanted to teach "proper religious values." This shows that in the early modern period, Ottomans and Europeans were similar in their ideas about how schools should be managed and what they should be primarily focused on. Thus, Ottoman madrasas were very similar to present day schools in the sense that they offered a wide range of studies; however, these studies, in their ultimate objective, aimed to further solidify and consolidate Islamic practices and theories.

Curricula

As is previously mentioned, religion dominated much of the knowledge and teachings that were endowed upon students. "Religious learning as the only true science, whose sole aim was the understanding of God's word."

The following is taken from İnalcık.

- A) Calligraphic sciences—such as styles of writing.

- B) Oral sciences—such as Arabic language, grammar and syntax.

- C) Intellectual sciences—logic in Islamic philosophy.

- D) Spiritual sciences—theoretical, such as Islamic theology and mathematics; and practical, such as Islamic ethics and politics.

Social life and the medrese

As with any other country during the Early Modern Period, such as Italy and Spain in Europe, the Ottoman social life was interconnected with the medrese. Medreses were built in as part of a Mosque complex where many programmes, such as aid to the poor through soup kitchens, were held under the infrastructure of a mosque, which reveals the interconnectedness of religion and social life during this period. "The mosques to which medreses were attached, dominated the social life in Ottoman cities." Social life was not dominated by religion only in the Muslim world of the Ottoman Empire; it was also quite similar to the social life of Europe during this period. As Goffman says: "Just as mosques dominated social life for the Ottomans, churches and synagogues dominated life for the Christians and Jews as well." Hence, social life and the medrese were closely linked, since medreses taught many curricula, such as religion, which highly governed social life in terms of establishing orthodoxy. "They tried moving their developing state toward Islamic orthodoxy." Overall, the fact that mosques contained medreses comes to show the relevance of education to religion in the sense that education took place within the framework of religion and religion established social life by trying to create a common religious orthodoxy. Hence, medreses were simply part of the social life of society as students came to learn the fundamentals of their societal values and beliefs.

Maghreb

In northwestern Africa (the Maghrib or Maghreb), including Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, the appearance of madrasas was delayed until after the fall of the Almohad dynasty, who espoused a reformist doctrine generally considered unorthodox by other Sunnis. As such, it only came to flourish in the region in the 13th century, under the Marinid and Hafsid dynasties which succeeded them. In Tunisia (or Ifriqiya), the earliest Hafsid madrasa was the Madrasat al-Ma'raḍ, founded in Tunis in 1252 and followed by many others. In Morocco, the first madrasa was the Madrasa as-Saffarin built in Fes in 1271, followed by many others constructed around the country. The Marinids also built madrasas in Algeria, particularly in Tlemcen.

As elsewhere, rulers in the Maghreb built madrasas to bolster their political legitimacy and that of their dynasty. The Marinids used their patronage of madrasas to cultivate the loyalty of Morocco's influential but independent religious elites and also to portray themselves to the general population as protectors and promoters of orthodox Sunni Islam. Madrasas also served to train the scholars and educated elites who generally operated the state bureaucracy. A number of madrasas also played a supporting role to major learning institutions like the older Qarawiyyin Mosque-University and the al-Andalusiyyin Mosque (both located in Fes) because they provided accommodations for students coming from other cities. Many of these students were poor, seeking sufficient education to gain a higher position in their home towns, and the madrasas provided them with basic necessities such as lodging and bread. However, the madrasas were also teaching institutions in their own right and offered their own courses, but usually with much narrower and more limited curriculums than the Qarawiyyin. The Bou Inania Madrasa in Fes, distinguished itself from other madrasas by its size and by being the only madrasa which also officially functioned as a public Friday mosque.

While some historical madrasas in Morocco remained in use well into the 20th century, most are no longer used for their original purpose following the reorganization of the Moroccan education system under French colonial rule and in the period following independence in 1956. Likewise, while some madrasas are still used for learning in Tunisia, many have since been converted to other uses in modern times.

Iran

Twelver Shi'ism has been the official religion of Iran since the Safavids declared it to be at the beginning of the 16th century, and the number of Shiʿite madrasas in Iran (or Persia) grew rapidly from that time on. Since 1979, the Islamic Republic of Iran, the head of state ("Supreme Leader"), has been a Twelver Shi'i faqih cleric. ("The vast majority" of the population is Twelver Shia Muslim. There are nearly three hundred thousand clerics in Iran's seminaries.

20th century

Historically, its estimated that there were about 5,000 religious students in Iran/Persia in 1924–25, but, that number dropped sharply owing to the anticlerical policy of Reżā Shah (1925–41), and made a gradual comeback—though lagging behind growth of Iran's population, "between 1920 and 1979 the Persian population tripled ... but enrollment in madrasas only doubled"—in the four decades before the revolution when his son (Mohammad Reza Pahlavi) ruled. At the biggest religious center in Iran, Qom, stipends for students came from religious taxes starting in the 1920s.

South Asia

Afghanistan

As of early 2021, Afghanistan had some 5000 madrasas registered with the Ministry of Hajj and Religious Affairs (unregistered ones being uncounted) with around 250 in Kabul, including the Darul-Ulom Imam Abu Hanifa which has 200 teachers and 3000 students, and in all, some 380,000 students were enrolled in these government recognized madrasas, including 55,000 girls.

Bangladesh

There are three different madrasa education systems in Bangladesh: the original darse nizami system, the redesigned nizami system, and the higher syllabus alia nisab. The first two categories are commonly called Qawmi or non-government madrasas. Amongst them the most notable are Al-Jamiatul Ahlia Darul Ulum Moinul Islam in Hathazari, Al-Jamiah Al-Islamiah Patiya, in Patiya, and Jamia Tawakkulia Renga Madrasah in Sylhet.

In 2006 there were 15,000 registered Qawmi madrasas with the Befaqul Mudarressin of Bangladesh Qawmi Madrasah Education Board, though the figure could be well over double that number if unregistered madrasas were counted.

The madrasas regulated by the government through the Bangladesh Madrasah Education Board are called the Alia madrasas and they number some 7,000, offering, in addition to religious instruction, subjects such as English and science, and its graduates often complete their education in secular institutions, to the extent that some 32% of the university teachers in the humanities and the social sciences are graduates of these Alia madrasas.

India

In 2008, India's madrassas were estimated to number between 8000 and 30,000, the state of Uttar Pradesh hosting most of them, estimated by the Indian government to have 10,000 of those back then.

The majority of these schools follow the Hanafi school of thought. The religious establishment forms part of the mainly two large divisions within the country, namely the Deobandis, who dominate in numbers (of whom the Darul Uloom Deoband constitutes one of the biggest madrasas) and the Barelvis, who also make up a sizeable portion (Sufi-oriented). Some notable establishments include: Aljamea-tus-Saifiyah (Isma'ilism), Al Jamiatul Ashrafia, Mubarakpur, Manzar Islam Bareilly, Jamia Nizamdina New Delhi, Jamia Nayeemia Muradabad which is one of the largest learning centres for the Barelvis. The HR ministry of the government of India has recently declared that a Central Madrasa Board would be set up. This will enhance the education system of madrasas in India. Though the madrasas impart Quranic education mainly, efforts are on to include Mathematics, Computers and science in the curriculum.

In July 2015, the state government of Maharashtra created a stir when it de-recognised madrasa education, receiving criticism from several political parties with the NCP accusing the ruling BJP of creating Hindu-Muslim friction in the state, and Kamal Farooqui of the All India Muslim Personal Law Board saying it was "ill-designed"

In March 2024, the Allahabad High Court in Uttar Pradesh declared the Madrasa Act of 2004 to be unconstitutional, according to a court order, while ordering the state government to move students enrolled in the Islamic system into mainstream schools.

In Kerala

Main article: Arabic CollegeMost of the Muslims of Kerala follow the traditional Shāfiʿī school of religious law (known in Kerala as the traditionalist 'Sunnis') while a large minority follow modern movements that developed within Sunni Islam. The latter section consists of majority Salafists (the Mujahids) and the minority Islamists (political Islam).

- A 'madrasa' in Kerala refers to an extra-curricular institution where children receive basic (Islamic) religious and Arabic language instruction.

- The so-called 'Arabic Colleges' of Kerala are the equivalent of north Indian madrasas.

Pakistan

Main article: Madrassas in PakistanIt is sometimes speculated that parents send their children to madrasas in Pakistan due to the inability to afford a good education. Although Madrasas are free they do provide adequate education for their students. It is sometimes speculated that due to lower quality of education those who finish have a hard time finding employment. Those who attended Madrasas have problem finding a job soon after. The education those receive madrasas in Pakistan closely resembles public institutions in the United States.

The madrasas rose as colleges of learning in the Islamic world in the 11th century, though there were institutions of learning earlier. They catered not only to the religious establishment, though that was the dominant influence over them, but also the secular one. To the latter they supplied physicians, administrative officials, judges and teachers. Today many registered madrasas are working effectively and coping up with modern education system such as Jamia-tul-Madina, which is a chain of Islamic schools in Pakistan and in European and other countries established by Dawat-e-Islami. The Jamia-tul-Madina are also known as Faizan-e-Madina. Dawat-e-Islami has grown its network of madrasas from Pakistan to Europe. In today's time the most centralized location of madrasas is in Pakistan. Although Pakistan hold the most Madrasas the number is still growing in many different countries.

Nepal

Nepal has 907 madrasas recognized on the same level as government schools but the total number in the country is around 4000.

Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia, Muslim students have a choice of attending a secular government or an Islamic school. Madrasas or Islamic schools are known as Sekolah Agama (Malay: religious school) in Malaysia and Indonesia, โรงเรียนศาสนาอิสลาม (Thai: school of Islam) in Thailand and madaris in the Philippines. In countries where Islam is not the majority or state religion, Islamic schools are found in regions such as southern Thailand (near the Thai-Malaysian border) and the southern Philippines in Mindanao, where a significant Muslim population can be found.

Indonesia

Main article: PesantrenThe number of madrasas more than doubled from 2002/2003 to 2011/2012, going from 63,000 to 145,000, unrecognized madrasas accounting for 17% of all schools in the country while the recognized madrasas account for nearly 1/3 of the secondary schools.

The word madrasah in Indonesia is also refer to secular-style public and private schools with more Islamic subjects in its curriculum. There are several levels of madrasah: Madrasah Ibtidaiyah (MI, the equivalent of elementary school), Madrasah Tsanawiyah (MTs, the equivalent of junior high school), Madrasah Aliyah (MA, the equivalent of senior high school), and Madrasah Aliyah Kejuruan (MAK, the equivalent of vocational high school).

Singapore

Main article: Madrasahs in Singapore

In Singapore, madrasahs are private schools which are overseen by Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura (MUIS, Islamic Religious Council of Singapore). There are six Madrasahs in Singapore, catering to students from Primary 1 to Secondary 4 (and junior college equivalent, or "Pre-U", at several schools). Four Madrasahs are coeducational and two are for girls. Students take a range of Islamic Studies subjects in addition to mainstream MOE curriculum subjects and sit for the PSLE and GCE 'O' Levels like their peers. In 2009, MUIS introduced the "Joint Madrasah System" (JMS), a joint collaboration of Madrasah Al-Irsyad Al-Islamiah primary school and secondary schools Madrasah Aljunied Al-Islamiah (offering the ukhrawi, or religious stream) and Madrasah Al-Arabiah Al-Islamiah (offering the academic stream). The JMS aims to introduce the International Baccalaureate (IB) programme into the Madrasah Al-Arabiah Al-Islamiah by 2019. Students attending a madrasah are required to wear the traditional Malay attire, including the songkok for boys and tudong for girls, in contrast to mainstream government schools which ban religious headgear as Singapore is officially a secular state. Students who wish to attend a mainstream school may opt to take classes on weekends at the madrasah instead of enrolling full-time.

Philippines