| John Ashley | |

|---|---|

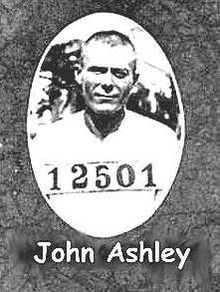

Police mugshot of John Ashley, c. 1914, from the Florida State Archives Police mugshot of John Ashley, c. 1914, from the Florida State Archives | |

| Born | John Hopkin Ashley (1888-03-19)March 19, 1888 near Fort Myers, Florida, US |

| Died | November 1, 1924(1924-11-01) (aged 36) St. Sebastian River Bridge, Roseland, Florida, US |

| Cause of death | Killed by police |

| Other names | King of the Everglades, Swamp Bandit |

| Criminal status | Escaped in 1918; recaptured in 1921 Escaped in 1923 |

| Spouse | Laura Upthegrove |

| Conviction(s) | Armed robbery (1916) |

| Criminal penalty | 17 years imprisonment |

John Hopkin Ashley (March 19, 1888 – November 1, 1924) was an American outlaw, bank robber, bootlegger, and occasional pirate active in southern Florida during the 1910s and 1920s. Between 1915 and 1924, the self-styled "King of the Everglades" or "Swamp Bandit" operated from various hideouts in the Florida Everglades. His gang robbed nearly $1 million from at least 40 banks while at the same time hijacking numerous shipments of illegal whiskey being smuggled into the state from the Bahamas. Indeed, Ashley's gang was so effective that rum-running on the Florida coast virtually ceased while the gang was active. His two-man raid on the West End in the Bahamas in 1924 marked the first time in over a century that American pirates had attacked a British Crown colony.

Among poor Florida "crackers", he was considered a folk hero who represented a symbol of resistance to bankers, lawmen and wealthy landowners. Ashley's activities also hindered Prohibition bootleggers in major cities, whose importation of foreign liquor undermined local moonshiners. Even the newspapers of the era frequently compared him to Jesse James. Almost every major crime in Florida was blamed on Ashley and his gang and one Florida official called him the greatest threat to the state since the Seminole Wars. His near 13-year feud with Palm Beach County Sheriff George B. Baker ended in the death of Ashley and his three lieutenants in 1924.

Biography

Early life and Desoto Tiger murder

John Ashley was born and raised in the backwoods country along the Caloosahatchee River in the community of Buckingham, Florida, near Fort Myers, Florida. He was one of nine children born to Joe Ashley, a poor Florida woodsman, who made his living by fishing, hunting, and trapping otters. The Ashley family moved from Fort Myers to Pompano in the 1890s, where Joe Ashley and his older sons worked on the new railroad being built by industrialist Henry Flagler. In 1911, Joe moved his family to West Palm Beach and briefly served as county sheriff. John Ashley spent much of his youth in the Florida Everglades and, like his father, became a skilled trapper and alligator hunter.

On December 29, 1911, a dredging crew working near Lake Okeechobee discovered the body of Seminole trapper Desoto Tiger. An investigation was held and John Ashley soon came under suspicion. According to fellow Seminole Jimmy Gopher, Ashley had been last seen with Tiger traveling in a canoe together with a boatload of otter hides to sell at a local market. Authorities were later told by fur traders in Miami, the Girtman Brothers, that John Ashley had sold them the hides for $1,200; the previous day he had also been arrested in West Palm Beach on a charge of "recklessly displaying firearms". Two deputies, S.A. Barfield and Bob Hannon, found Ashley camping in a palmetto thicket near Hobe Sound and attempted to take him into custody. However, they were surprised by his brother Bob Ashley and were disarmed at gunpoint. John Ashley then sent the officers back with a message for Sheriff George B. Baker "not to send anymore chicken-hearted men with rifles or they are apt to get hurt".

In his trial for the murder of Tiger in 1910, despite overwhelming evidence, Ashley was not convicted. In a second trial in 1915, he was sentenced to hang for Tiger's murder, but that conviction was overturned by the Florida Supreme Court. Ashley repeatedly escaped from various local jails and eluded law enforcement until he was gunned down at the St. Sebastian River bridge in Roseland. Although he was incarcerated for other crimes, Ashley never served any time for the murder of Desoto Tiger.

Formation of the Ashley Gang

When the Seminole Nation raised protest over the murder, the US federal government threatened to intervene. John Ashley fled to New Orleans for a year or two before returning to Florida around 1914. He may have worked as a logger in Seattle, and later claimed to have robbed a bank in Canada. Upon his return, he surrendered himself to authorities in West Palm Beach where he was imprisoned until his trial. Ashley may have hoped that a hometown jury might sympathize with him, however the local prosecutor petitioned the judge for a change of venue to Miami. Hearing of the prosecutor's plans, he decided to escape. According to contemporary accounts, Ashley was being escorted to his cell by Sheriff Baker's son, Robert C. Baker, when he suddenly broke away, ran out an unlocked door and climbed a 10-foot fence to freedom.

He and his brothers then became outlaws and, with other occasional partners, formed a criminal gang. In 1915, he and Bob Ashley robbed an FEC passenger train with Chicago mobster Kid Lowe. Their first attempt was less than successful as they failed to agree on who would collect valuables from the passengers and who would rob the mail car. That same year, they stole $45,000 in silver and cash in a daring daylight bank robbery in Stuart, Florida. During their getaway however, Lowe accidentally shot John Ashley in the jaw, costing him the sight in one of his eyes. When Ashley attempted to get medical attention for his eye, he was captured and held in the Dade County jailhouse to await trial. He was taken to Miami to stand trial for the murder of Tiger, however, the state's attorney believed that that had a better chance of prosecuting Ashley for the Stuart robberies in West Palm Beach.

On June 2, 1915, Bob Ashley attempted to break his brother John out of jail. Entering the jailer's house, Bob Ashley shot Deputy Sheriff Wilber W. Hendrickson at point-blank range and left with his jail keys. He then ran from the house to the garage where gang members had left him a getaway car. When he found he was unable to drive the particular car left for him, he attempted to force several men at gunpoint to drive the car for him. Each of the men claimed to not know how to drive the car either so Bob Ashley jumped on the running board of a passing truck and forced the driver, T.H. Duckett, to take him out of town. A deputy, officer J.R. Riblet, spotted Ashley and gave chase. When the truck suddenly stalled in the middle of the street, a shootout occurred resulting in the deaths of both Bob Ashley and Riblet. Angered by Bob's killing spree, several thousand Miami residents threatened the jailhouse and talked of lynching John Ashley in his cell. It was only after police paraded the body of Bob Ashley through the streets that the mob dispersed.

Kid Lowe, possibly out of guilt for shooting John Ashley, sent a note to Dade County sheriff Dan Hardie demanding the release of Ashley:

Dear Sir,

We were in your city at the time one of our gang, young Bob Ashley, was brutally shot to death by your officers and now your town can expect to feel the result of it any hour. And if John Ashley is not fairly dealt with and given a fair trial and turned loose simply for the life of a God-damn Seminole Indian we expect to shoot up the hole God-damn town regardless of what the results might be. We expect to make our appearance at an early date.

However, no attack from the Ashley Gang came and the town proceeded with the prosecution. On November 23, 1916, John Ashley pleaded guilty to robbery and was sentenced to 17 years in the state penitentiary at Raiford.

Ashley and the Queen of the Everglades

Prior to his arrest, Ashley began a relationship with Laura Upthegrove. Upthegrove acted primarily as the gang's lookout. Whenever she heard authorities were nearing one of Ashley's hideouts, she would drive her car through secret backwoods trails, often without headlights if at night, to warn fellow gang members. Laura also cased banks and served as a getaway driver. While they were together, she became known as the "Queen of the Everglades", and took a central role in the gang while Ashley was incarcerated.

Escape and foray into piracy

Ashley behaved as a model prisoner for two years until escaping from a road camp, with the assistance of fellow bank robber Tom Maddox, on March 31, 1918. With the start of Prohibition, he began moonshining with his gang before his eventual recapture in June 1921. The Ashley gang continued moonshining in his absence, maintaining their many stills in the woods of central Florida, and began hijacking rum runners as well under Clarence Middleton or Roy Matthews. Joe Ashley had several stills in Palm Beach County while John's brothers Ed and Frank Ashley ran liquor from the Bahamas to Jupiter Inlet and Stuart. While John Ashley was still in jail, his brothers disappeared while on a return voyage from Bimini in October 1921.

The circumstances surrounding Ashley's third and final escape remain a mystery, only that he "vanished from his cell", and returned to bank robbery with his gang. In one of their more memorable robberies, the gang managed to rob the Stuart bank a second time in September 1923 after Ashley's teenage nephew Hanford Mobley sneaked into the building disguised as a woman and escaped with several thousand dollars. Shortly after the robbery, Mobley and Middleton were caught in Plant City and Matthews in Georgia, however all escaped and were back together in the woods near Gomez by the end of the year.

In November 1923, the gang robbed $23,000 in cash and securities from a bank in Pompano. Like many of their heists, this was followed by reckless celebrating in the streets. After wrapping the loot in a bedsheet, they slowly drove through the middle of the town in a stolen taxi. They waved a bottle of whiskey to onlookers and shouted "We got it all!". Leaving the town, they crossed a canal and disappeared into the swamp near Clewiston. Ashley supposedly left a bullet with one of the victims to give to Sheriff Baker if he "ever got out to the 'Glades".

The gang leader also tried his hand at piracy, intercepting many rum-runners along the coast of southern Florida. Many chose to pay the Ashleys protection money. In 1924, he and his nephew Hanford Mobley stole a sea skiff and led a raid against rum-runners in the Bahamas' West End leaving with $8,000 from four wholesale liquor warehouses. Hours before the raid, however, an express boat carrying a quarter-million dollars had left for Nassau.

Within a few years of Prohibition, the Ashley Gang was so feared by Florida bootleggers that many began deserting the area looking for safer routes far out of reach of the gang. As a result, the Ashleys' opportunities for liquor piracy dwindled and they eventually returned to bank robbery as their primary activity.

Feud with Sheriff Baker

By this time, Ashley and Sheriff Baker were engaging in a personal feud. The sheriff had received a tip from a local car salesman and had set a trap on the eve of the Bahamas raid. Suspecting that the law might be on to his plans, Ashley changed his route at the last minute and sailed through St. Lucie Inlet, narrowly avoiding capture.

Baker spent months searching the Everglades and came up empty-handed. This was in part the result of help from fellow Florida "crackers" and a "grapevine telegraph of the 'glades". Per historian Steve Carr, Baker was a corrupt sheriff who wasn't above shaking down poor people trying to live off the land. Since he also had ties to the Ku Klux Klan, the local Black community helped the Ashley gang.

In early 1924, Baker finally got a lead on Ashley's location. Through his informants, Baker learned that Ashley was staying with family members in a moonshiner's cabin hidden in a swamp about 2 miles (3.2 km) south of the Ashley family home. The short bushes and palmetto scrub made it very difficult, if not impossible, to approach the cabin, making it an ideal hideout. Baker was determined to capture Ashley and, with weapons from the Florida National Guard and deputized civilians, made plans to surround the cabin and starve him out. On January 10, 1924, he sent eight of his deputies to the house early in the morning; they were in position by dawn.

Just as the deputies were about to make their move, Ashley's dog began barking at the lawmen. The deputies fired at the dog, causing Ashley to return fire; he killed one of the deputies, the sheriff's cousin Fred Baker, in the resulting gunfight. His father, Joe Ashley, was killed in his bunk while his partner, Albert Miller, and Laura were seriously wounded by buckshot from a deputy's shotgun. Forced to leave his wife behind, Ashley escaped through a secret entrance; his wife's screaming caused the deputies to hold their fire, which helped enable the escape. Despite a manhunt involving 200 men, during which the homes of both Joe Ashley and Hanford Mobley were burned (as well as a small grocery owned by Miller), Ashley remained in the area where Laura was being held by police. He hoped to plan a jail break for her, as well as avenge the death of his father, but as more time passed he left for California to lie low.

Death

Ashley returned to Florida and spent several months with his gang planning their revenge. He apparently developed a plot to kill Sheriff Baker at the Jacksonville courthouse following his election in November.

On November 1, 1924, Baker received a tip from an anonymous source, believed to be a gang member's girlfriend (or a disgruntled brother-in-law), that Ashley would be travelling up the coast on the Dixie Highway to rob a bank in Jacksonville. That same day, Baker arranged an ambush at the bridge over the St. Sebastian River in Roseland, blocking the road with a chain with a red lantern across the bridge. As the bridge was out of his jurisdiction, the actual operation was overseen by the sheriff of St. Lucie County, J.R. Merritt, along with three of Baker's deputies. An hour after the ambush was laid, Ashley's black touring car was spotted. Once it stopped at the bridge, the deputies approached the car from behind and ordered the gang out of the vehicle. According to the official story, the deputies searched the car and found several guns while Ashley, Ray Lynn, Hanford Mobley, and Clarence Middleton were lined up outside the car. John Ashley then pulled out a concealed weapon, causing the deputies to open fire. Ashley and his three partners were killed in the shootout.

There are two alternate versions, however. The first, according to two men who witnessed their arrest, claim they had also been stopped on the bridge and saw the officers approach Ashley's car behind them. When police directed them to leave the scene, both men insisted that Ashley and the others were handcuffed. There were marks that could have been made by handcuffs, however police claimed the marks were the result of the coroner examining the bodies. This explanation was accepted by a coroner's jury. A third theory, one thought to be closer to the truth, was offered in the 1996 book Florida's Ashley Gang by historian Ada Coats Williams: an unidentified deputy claimed that, while in handcuffs, Ashley made a sudden move forward and dropped his hands, causing officers to fire. He had told Williams this during the 1950s on the promise that she not reveal this information until all the deputies had died. At the time of Ashley's death, however, it was widely believed among poor "crackers" that he had been executed by the police as a form of frontier justice.

Aftermath

After her husband's death, Laura Upthegrove lived under an assumed name in western Florida for a time. In the next two years, she was arrested on several occasions before eventually opening a gas station at Canal Point on Lake Okeechobee. She later moved in with her mother in Upthegrove Beach. On August 6, 1927, she died during an argument with a man trying to buy moonshine from her. In the heat of the moment, she swallowed a bottle of disinfectant and died within minutes. It is unclear whether it was an accident, as some claim she mistook it for a bottle of gin, but it was widely reported that she had committed suicide. She was 30 years old.

A few members of the Ashley gang still remained, although they were eventually killed, captured, or fled the state within a few years. Only $32,000 of the gang's fortune was ever recovered; it was found only with the help of ex-gang member Joe Tracy. A reported $110,000 and other Everglades stashes have never been reported as found.

Ashley, Mobley, and Lynn (Middleton was buried in Jacksonville) were buried in a family cemetery, the Little Ashley Cemetery, outside Gomez, where the Ashley family home once stood. Six members of the Ashley clan were buried there, all having died a violent death with the exception of an infant grandchild. The cemetery eventually became part of an exclusive residential neighborhood, Mariner Sands, and it is rumored that some unrecovered loot is buried somewhere on this property. A state historical marker was placed at Sebastian Inlet but disappeared when a new bridge was built over the river.

In popular culture

- John Ashley was portrayed by James Carlos Blake in his 2000 historical novel Red Grass River: A Legend, winner of the 1999 Chautauqua South Book Award and the 2013 French Grand Prix du Roman Noir Étranger.

- John Ashley and Laura Upthegrove were the subject of the 1973 film Little Laura and Big John starring Fabian and Karen Black.

- The Ashley Gang is a Folk/Americana/Acoustic Rock band based in Sebastian, Florida. It is named after the gang and its original songs include, "The Ashley Gang".

- The Destroyer song "Blue Eyes," from the 2011 album Kaputt, features a lyric referencing the "King of the Everglades."

References

- General

- "What Really Happened The Night Ashley Gang Was Killed?". Orlando Sentinel. June 26, 1933. Archived from the original on October 4, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- Specific

- ^ Burnett, Gene M. Florida's Past: People and Events That Shaped the State. Vol. 3. Sarasota: Pineapple Press Inc, 1996. (pg. 85-89) ISBN 1-56164-115-4

- ^ Moran, Mark, Charlie Carlson and Mark Sceurman. Weird Florida: Your Travel Guide to Florida's Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets. New York: Sterling Publishing Company, 2009. (pg. 101-104) ISBN 1-4027-6684-X

- ^ Reilly, Benjamin. Tropical Surge: A History of Ambition and Disaster on the Florida Shore. Sarasota: Pineapple Press Inc, 2005. (pg. 186-192) ISBN 1-56164-330-0

- ^ McGoun, William E. Southeast Florida Pioneers: The Palm and Treasure Coasts. Sarasota: Pineapple Press Inc, 1998. (pg. 136-140) ISBN 1-56164-157-X

- Cole, Stephanie; Ring, Natalie J. The Folly of Jim Crow: Rethinking the Segregated South. A & M University Press. p. 64.

- ^ Kleinberg, Eliot. Palm Beach Past: The Best of "Post Time". Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2006. (pg. 72) ISBN 1-59629-115-X

- "A Desperado on the Florida frontier". 9 October 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ Ling, Sally J. Run the Rum In: South Florida During Prohibition. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2007. (pg. 87, 89, 91) ISBN 1-59629-249-0

- Officer Down Memorial Page. "Deputy Sheriff Wilber W. Hendrickson, Dade County Sheriff's Department, Florida". ODMP.org. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- Officer Down Memorial Page. "Officer John Rhinehart "Bob" Riblet, Miami Police Department, Florida". ODMP.org. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- Tichy, John; Banta, Debbie; Walters, Judy (20 January 2022). "Local history: Rumrunning trade roared along Florida's Treasure Coast". TC Palm. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- "Funeral of deputy sheriff Morris Raiford Johns". Stuart Messenger. October 9, 1924.

Six robed Klansmen took part in the ceremony at the grave.

- Fontenay, Blake (February 25, 2022). "Black community helped Ashley Gang in fight against Treasure Coast corruption". TC Palm. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- Blake, James Carlos (2000). Red Grass River: A Legend. Harper Perennial. ISBN 9780380792429.

- Lloyd, Rob. You got me!--Florida. Sarasota: Pineapple Press Inc, 1999. (pg. 80) ISBN 1-56164-183-9

- eMinor. "The Ashley Gang | Folk from Sebastian, FL". ReverbNation. Retrieved 2022-02-14.

- "The Ashley gang". The Ashley gang. Retrieved 2022-02-14.

Further reading

- Stuart, Hix Cook. The Notorious Ashley Gang: A Saga of the King and Queen of the Everglades. Stuart, Florida: St. Lucie Printing Co., 1928.

- Williams, Ada Coats. Florida's Ashley Gang. Port Salerno, Florida: Florida Classics Library, 1996.

External links

- John Ashley at the National Museum of Crime & Punishment

- The Spanish Papers: Boca Raton, 1915-1950 by the Boca Raton Historical Society

- Indian River Lagoon early 1900s - The Dreaded Ashley Gang

- The Day the Ashley gang robbed the Pompano bank by Bud Garner

- The Ashley Gang: What really happened by Warren Sonne

- The Ashely Gang and Frontier Justice by Richard Procyk

- 1888 births

- 1924 deaths

- 20th-century pirates

- American bootleggers

- American bank robbers

- American pirates

- Criminals from Florida

- Deaths by firearm in Florida

- People from Fort Myers, Florida

- People from West Palm Beach, Florida

- People shot dead by law enforcement officers in the United States

- American gangsters of the interwar period