Keystroke logging, often referred to as keylogging or keyboard capturing, is the action of recording (logging) the keys struck on a keyboard, typically covertly, so that a person using the keyboard is unaware that their actions are being monitored. Data can then be retrieved by the person operating the logging program. A keystroke recorder or keylogger can be either software or hardware.

While the programs themselves are legal, with many designed to allow employers to oversee the use of their computers, keyloggers are most often used for stealing passwords and other confidential information. Keystroke logging can also be utilized to monitor activities of children in schools or at home and by law enforcement officials to investigate malicious usage.

Keylogging can also be used to study keystroke dynamics or human-computer interaction. Numerous keylogging methods exist, ranging from hardware and software-based approaches to acoustic cryptanalysis.

History

In the mid-1970s, the Soviet Union developed and deployed a hardware keylogger targeting typewriters. Termed the "selectric bug", it measured the movements of the print head of IBM Selectric typewriters via subtle influences on the regional magnetic field caused by the rotation and movements of the print head. An early keylogger was written by Perry Kivolowitz and posted to the Usenet newsgroup net.unix-wizards, net.sources on November 17, 1983. The posting seems to be a motivating factor in restricting access to /dev/kmem on Unix systems. The user-mode program operated by locating and dumping character lists (clients) as they were assembled in the Unix kernel.

In the 1970s, spies installed keystroke loggers in the US Embassy and Consulate buildings in Moscow. They installed the bugs in Selectric II and Selectric III electric typewriters.

Soviet embassies used manual typewriters, rather than electric typewriters, for classified information—apparently because they are immune to such bugs. As of 2013, Russian special services still use typewriters.

Application of keylogger

Software-based keyloggers

A software-based keylogger is a computer program designed to record any input from the keyboard. Keyloggers are used in IT organizations to troubleshoot technical problems with computers and business networks. Families and businesspeople use keyloggers legally to monitor network usage without their users' direct knowledge. Microsoft publicly stated that Windows 10 has a built-in keylogger in its final version "to improve typing and writing services". However, malicious individuals can use keyloggers on public computers to steal passwords or credit card information. Most keyloggers are not stopped by HTTPS encryption because that only protects data in transit between computers; software-based keyloggers run on the affected user's computer, reading keyboard inputs directly as the user types.

From a technical perspective, there are several categories:

- Hypervisor-based: The keylogger can theoretically reside in a malware hypervisor running underneath the operating system, which thus remains untouched. It effectively becomes a virtual machine. Blue Pill is a conceptual example.

- Kernel-based: A program on the machine obtains root access to hide in the OS and intercepts keystrokes that pass through the kernel. This method is difficult both to write and to combat. Such keyloggers reside at the kernel level, which makes them difficult to detect, especially for user-mode applications that do not have root access. They are frequently implemented as rootkits that subvert the operating system kernel to gain unauthorized access to the hardware. This makes them very powerful. A keylogger using this method can act as a keyboard device driver, for example, and thus gain access to any information typed on the keyboard as it goes to the operating system.

- API-based: These keyloggers hook keyboard APIs inside a running application. The keylogger registers keystroke events as if it was a normal piece of the application instead of malware. The keylogger receives an event each time the user presses or releases a key. The keylogger simply records it.

- Form grabbing based: Form grabbing-based keyloggers log Web form submissions by recording the form data on submit events. This happens when the user completes a form and submits it, usually by clicking a button or pressing enter. This type of keylogger records form data before it is passed over the Internet.

- JavaScript-based: A malicious script tag is injected into a targeted web page, and listens for key events such as

onKeyUp(). Scripts can be injected via a variety of methods, including cross-site scripting, man-in-the-browser, man-in-the-middle, or a compromise of the remote website. - Memory-injection-based: Memory Injection (MitB)-based keyloggers perform their logging function by altering the memory tables associated with the browser and other system functions. By patching the memory tables or injecting directly into memory, this technique can be used by malware authors to bypass Windows UAC (User Account Control). The Zeus and SpyEye trojans use this method exclusively. Non-Windows systems have protection mechanisms that allow access to locally recorded data from a remote location. Remote communication may be achieved when one of these methods is used:

- Data is uploaded to a website, database or an FTP server.

- Data is periodically emailed to a pre-defined email address.

- Data is wirelessly transmitted employing an attached hardware system.

- The software enables a remote login to the local machine from the Internet or the local network, for data logs stored on the target machine.

Keystroke logging in writing process research

Since 2006, keystroke logging has been an established research method for the study of writing processes. Different programs have been developed to collect online process data of writing activities, including Inputlog, Scriptlog, Translog and GGXLog.

Keystroke logging is used legitimately as a suitable research instrument in several writing contexts. These include studies on cognitive writing processes, which include

- descriptions of writing strategies; the writing development of children (with and without writing difficulties),

- spelling,

- first and second language writing, and

- specialist skill areas such as translation and subtitling.

Keystroke logging can be used to research writing, specifically. It can also be integrated into educational domains for second language learning, programming skills, and typing skills.

Related features

Software keyloggers may be augmented with features that capture user information without relying on keyboard key presses as the sole input. Some of these features include:

- Clipboard logging. Anything that has been copied to the clipboard can be captured by the program.

- Screen logging. Screenshots are taken to capture graphics-based information. Applications with screen logging abilities may take screenshots of the whole screen, of just one application, or even just around the mouse cursor. They may take these screenshots periodically or in response to user behaviors (for example, when a user clicks the mouse). Screen logging can be used to capture data inputted with an on-screen keyboard.

- Programmatically capturing the text in a control. The Microsoft Windows API allows programs to request the text 'value' in some controls. This means that some passwords may be captured, even if they are hidden behind password masks (usually asterisks).

- The recording of every program/folder/window opened including a screenshot of every website visited.

- The recording of search engines queries, instant messenger conversations, FTP downloads and other Internet-based activities (including the bandwidth used).

Hardware-based keyloggers

Hardware-based keyloggers do not depend upon any software being installed as they exist at a hardware level in a computer system.

- Firmware-based: BIOS-level firmware that handles keyboard events can be modified to record these events as they are processed. Physical and/or root-level access is required to the machine, and the software loaded into the BIOS needs to be created for the specific hardware that it will be running on.

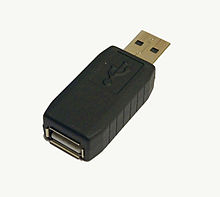

- Keyboard hardware: Hardware keyloggers are used for keystroke logging utilizing a hardware circuit that is attached somewhere in between the computer keyboard and the computer, typically inline with the keyboard's cable connector. There are also USB connector-based hardware keyloggers, as well as ones for laptop computers (the Mini-PCI card plugs into the expansion slot of a laptop). More stealthy implementations can be installed or built into standard keyboards so that no device is visible on the external cable. Both types log all keyboard activity to their internal memory, which can be subsequently accessed, for example, by typing in a secret key sequence. Hardware keyloggers do not require any software to be installed on a target user's computer, therefore not interfering with the computer's operation and less likely to be detected by software running on it. However, its physical presence may be detected if, for example, it is installed outside the case as an inline device between the computer and the keyboard. Some of these implementations can be controlled and monitored remotely using a wireless communication standard.

- Wireless keyboard and mouse sniffers: These passive sniffers collect packets of data being transferred from a wireless keyboard and its receiver. As encryption may be used to secure the wireless communications between the two devices, this may need to be cracked beforehand if the transmissions are to be read. In some cases, this enables an attacker to type arbitrary commands into a victim's computer.

- Keyboard overlays: Criminals have been known to use keyboard overlays on ATMs to capture people's PINs. Each keypress is registered by the keyboard of the ATM as well as the criminal's keypad that is placed over it. The device is designed to look like an integrated part of the machine so that bank customers are unaware of its presence.

- Acoustic keyloggers: Acoustic cryptanalysis can be used to monitor the sound created by someone typing on a computer. Each key on the keyboard makes a subtly different acoustic signature when struck. It is then possible to identify which keystroke signature relates to which keyboard character via statistical methods such as frequency analysis. The repetition frequency of similar acoustic keystroke signatures, the timings between different keyboard strokes and other context information such as the probable language in which the user is writing are used in this analysis to map sounds to letters. A fairly long recording (1000 or more keystrokes) is required so that a large enough sample is collected.

- Electromagnetic emissions: It is possible to capture the electromagnetic emissions of a wired keyboard from up to 20 metres (66 ft) away, without being physically wired to it. In 2009, Swiss researchers tested 11 different USB, PS/2 and laptop keyboards in a semi-anechoic chamber and found them all vulnerable, primarily because of the prohibitive cost of adding shielding during manufacture. The researchers used a wide-band receiver to tune into the specific frequency of the emissions radiated from the keyboards.

- Optical surveillance: Optical surveillance, while not a keylogger in the classical sense, is nonetheless an approach that can be used to capture passwords or PINs. A strategically placed camera, such as a hidden surveillance camera at an ATM, can allow a criminal to watch a PIN or password being entered.

- Physical evidence: For a keypad that is used only to enter a security code, the keys which are in actual use will have evidence of use from many fingerprints. A passcode of four digits, if the four digits in question are known, is reduced from 10,000 possibilities to just 24 possibilities (10 versus 4! ). These could then be used on separate occasions for a manual "brute force attack".

- Smartphone sensors: Researchers have demonstrated that it is possible to capture the keystrokes of nearby computer keyboards using only the commodity accelerometer found in smartphones. The attack is made possible by placing a smartphone near a keyboard on the same desk. The smartphone's accelerometer can then detect the vibrations created by typing on the keyboard and then translate this raw accelerometer signal into readable sentences with as much as 80 percent accuracy. The technique involves working through probability by detecting pairs of keystrokes, rather than individual keys. It models "keyboard events" in pairs and then works out whether the pair of keys pressed is on the left or the right side of the keyboard and whether they are close together or far apart on the QWERTY keyboard. Once it has worked this out, it compares the results to a preloaded dictionary where each word has been broken down in the same way. Similar techniques have also been shown to be effective at capturing keystrokes on touchscreen keyboards while in some cases, in combination with gyroscope or with the ambient-light sensor.

- Body keyloggers: Body keyloggers track and analyze body movements to determine which keys were pressed. The attacker needs to be familiar with the keys layout of the tracked keyboard to correlate between body movements and keys position, although with a suitably large sample this can be deduced. Tracking audible signals of the user' interface (e.g. a sound the device produce to informs the user that a keystroke was logged) may reduce the complexity of the body keylogging algorithms, as it marks the moment at which a key was pressed.

Cracking

Writing simple software applications for keylogging can be trivial, and like any nefarious computer program, can be distributed as a trojan horse or as part of a virus. What is not trivial for an attacker, however, is installing a covert keystroke logger without getting caught and downloading data that has been logged without being traced. An attacker that manually connects to a host machine to download logged keystrokes risks being traced. A trojan that sends keylogged data to a fixed e-mail address or IP address risks exposing the attacker.

Trojans

Researchers Adam Young and Moti Yung discussed several methods of sending keystroke logging. They presented a deniable password snatching attack in which the keystroke logging trojan is installed using a virus or worm. An attacker who is caught with the virus or worm can claim to be a victim. The cryptotrojan asymmetrically encrypts the pilfered login/password pairs using the public key of the trojan author and covertly broadcasts the resulting ciphertext. They mentioned that the ciphertext can be steganographically encoded and posted to a public bulletin board such as Usenet.

Use by police

In 2000, the FBI used FlashCrest iSpy to obtain the PGP passphrase of Nicodemo Scarfo, Jr., son of mob boss Nicodemo Scarfo. Also in 2000, the FBI lured two suspected Russian cybercriminals to the US in an elaborate ruse, and captured their usernames and passwords with a keylogger that was covertly installed on a machine that they used to access their computers in Russia. The FBI then used these credentials to gain access to the suspects' computers in Russia to obtain evidence to prosecute them.

Countermeasures

The effectiveness of countermeasures varies because keyloggers use a variety of techniques to capture data and the countermeasure needs to be effective against the particular data capture technique. In the case of Windows 10 keylogging by Microsoft, changing certain privacy settings may disable it. An on-screen keyboard will be effective against hardware keyloggers; transparency will defeat some—but not all—screen loggers. An anti-spyware application that can only disable hook-based keyloggers will be ineffective against kernel-based keyloggers.

Keylogger program authors may be able to update their program's code to adapt to countermeasures that have proven effective against it.

Anti-keyloggers

Main article: Anti-keyloggerAn anti-keylogger is a piece of software specifically designed to detect keyloggers on a computer, typically comparing all files in the computer against a database of keyloggers, looking for similarities which might indicate the presence of a hidden keylogger. As anti-keyloggers have been designed specifically to detect keyloggers, they have the potential to be more effective than conventional antivirus software; some antivirus software do not consider keyloggers to be malware, as under some circumstances a keylogger can be considered a legitimate piece of software.

Live CD/USB

Rebooting the computer using a Live CD or write-protected Live USB is a possible countermeasure against software keyloggers if the CD is clean of malware and the operating system contained on it is secured and fully patched so that it cannot be infected as soon as it is started. Booting a different operating system does not impact the use of a hardware or BIOS based keylogger.

Anti-spyware / Anti-virus programs

Many anti-spyware applications can detect some software based keyloggers and quarantine, disable, or remove them. However, because many keylogging programs are legitimate pieces of software under some circumstances, anti-spyware often neglects to label keylogging programs as spyware or a virus. These applications can detect software-based keyloggers based on patterns in executable code, heuristics and keylogger behaviors (such as the use of hooks and certain APIs).

No software-based anti-spyware application can be 100% effective against all keyloggers. Software-based anti-spyware cannot defeat non-software keyloggers (for example, hardware keyloggers attached to keyboards will always receive keystrokes before any software-based anti-spyware application).

The particular technique that the anti-spyware application uses will influence its potential effectiveness against software keyloggers. As a general rule, anti-spyware applications with higher privileges will defeat keyloggers with lower privileges. For example, a hook-based anti-spyware application cannot defeat a kernel-based keylogger (as the keylogger will receive the keystroke messages before the anti-spyware application), but it could potentially defeat hook- and API-based keyloggers.

Network monitors

Network monitors (also known as reverse-firewalls) can be used to alert the user whenever an application attempts to make a network connection. This gives the user the chance to prevent the keylogger from "phoning home" with their typed information.

Automatic form filler programs

Main article: Form fillerAutomatic form-filling programs may prevent keylogging by removing the requirement for a user to type personal details and passwords using the keyboard. Form fillers are primarily designed for Web browsers to fill in checkout pages and log users into their accounts. Once the user's account and credit card information has been entered into the program, it will be automatically entered into forms without ever using the keyboard or clipboard, thereby reducing the possibility that private data is being recorded. However, someone with physical access to the machine may still be able to install software that can intercept this information elsewhere in the operating system or while in transit on the network. (Transport Layer Security (TLS) reduces the risk that data in transit may be intercepted by network sniffers and proxy tools.)

One-time passwords (OTP)

Using one-time passwords may prevent unauthorized access to an account which has had its login details exposed to an attacker via a keylogger, as each password is invalidated as soon as it is used. This solution may be useful for someone using a public computer. However, an attacker who has remote control over such a computer can simply wait for the victim to enter their credentials before performing unauthorized transactions on their behalf while their session is active.

Another common way to protect access codes from being stolen by keystroke loggers is by asking users to provide a few randomly selected characters from their authentication code. For example, they might be asked to enter the 2nd, 5th, and 8th characters. Even if someone is watching the user or using a keystroke logger, they would only get a few characters from the code without knowing their positions.

Security tokens

Use of smart cards or other security tokens may improve security against replay attacks in the face of a successful keylogging attack, as accessing protected information would require both the (hardware) security token as well as the appropriate password/passphrase. Knowing the keystrokes, mouse actions, display, clipboard, etc. used on one computer will not subsequently help an attacker gain access to the protected resource. Some security tokens work as a type of hardware-assisted one-time password system, and others implement a cryptographic challenge–response authentication, which can improve security in a manner conceptually similar to one time passwords. Smartcard readers and their associated keypads for PIN entry may be vulnerable to keystroke logging through a so-called supply chain attack where an attacker substitutes the card reader/PIN entry hardware for one which records the user's PIN.

On-screen keyboards

Most on-screen keyboards (such as the on-screen keyboard that comes with Windows XP) send normal keyboard event messages to the external target program to type text. Software key loggers can log these typed characters sent from one program to another.

Keystroke interference software

Keystroke interference software is also available. These programs attempt to trick keyloggers by introducing random keystrokes, although this simply results in the keylogger recording more information than it needs to. An attacker has the task of extracting the keystrokes of interest—the security of this mechanism, specifically how well it stands up to cryptanalysis, is unclear.

Speech recognition

Similar to on-screen keyboards, speech-to-text conversion software can also be used against keyloggers, since there are no typing or mouse movements involved. The weakest point of using voice-recognition software may be how the software sends the recognized text to target software after the user's speech has been processed.

Handwriting recognition and mouse gestures

Many PDAs and lately tablet PCs can already convert pen (also called stylus) movements on their touchscreens to computer understandable text successfully. Mouse gestures use this principle by using mouse movements instead of a stylus. Mouse gesture programs convert these strokes to user-definable actions, such as typing text. Similarly, graphics tablets and light pens can be used to input these gestures, however, these are becoming less common.

The same potential weakness of speech recognition applies to this technique as well.

Macro expanders/recorders

With the help of many programs, a seemingly meaningless text can be expanded to a meaningful text and most of the time context-sensitively, e.g. "en.wikipedia.org" can be expanded when a web browser window has the focus. The biggest weakness of this technique is that these programs send their keystrokes directly to the target program. However, this can be overcome by using the 'alternating' technique described below, i.e. sending mouse clicks to non-responsive areas of the target program, sending meaningless keys, sending another mouse click to the target area (e.g. password field) and switching back-and-forth.

Deceptive typing

Alternating between typing the login credentials and typing characters somewhere else in the focus window can cause a keylogger to record more information than it needs to, but this could be easily filtered out by an attacker. Similarly, a user can move their cursor using the mouse while typing, causing the logged keystrokes to be in the wrong order e.g., by typing a password beginning with the last letter and then using the mouse to move the cursor for each subsequent letter. Lastly, someone can also use context menus to remove, cut, copy, and paste parts of the typed text without using the keyboard. An attacker who can capture only parts of a password will have a larger key space to attack if they choose to execute a brute-force attack.

Another very similar technique uses the fact that any selected text portion is replaced by the next key typed. e.g., if the password is "secret", one could type "s", then some dummy keys "asdf". These dummy characters could then be selected with the mouse, and the next character from the password "e" typed, which replaces the dummy characters "asdf".

These techniques assume incorrectly that keystroke logging software cannot directly monitor the clipboard, the selected text in a form, or take a screenshot every time a keystroke or mouse click occurs. They may, however, be effective against some hardware keyloggers.

See also

- Anti-keylogger

- Black-bag cryptanalysis

- Computer surveillance

- Cybercrime

- Digital footprint

- Hardware keylogger

- Reverse connection

- Session replay

- Spyware

- Trojan horse

- Virtual keyboard

- Web tracking

References

- Nyang, DaeHun; Mohaisen, Aziz; Kang, Jeonil (2014-11-01). "Keylogging-Resistant Visual Authentication Protocols". IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing. 13 (11): 2566–2579. doi:10.1109/TMC.2014.2307331. ISSN 1536-1233. S2CID 8161528.

- Conijn, Rianne; Cook, Christine; van Zaanen, Menno; Van Waes, Luuk (2021-08-24). "Early prediction of writing quality using keystroke logging". International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education. 32 (4): 835–866. doi:10.1007/s40593-021-00268-w. hdl:10067/1801420151162165141. ISSN 1560-4292. S2CID 238703970.

- Use of legal software products for computer monitoring, keylogger.org

- "Keylogger". Oxford dictionaries. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2013-08-03.

- Keyloggers: How they work and how to detect them (Part 1), Secure List, "Today, keyloggers are mainly used to steal user data relating to various online payment systems, and virus writers are constantly writing new keylogger Trojans for this very purpose."

- Rai, Swarnima; Choubey, Vaaruni; Suryansh; Garg, Puneet (2022-07-08). "A Systematic Review of Encryption and Keylogging for Computer System Security". 2022 Fifth International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Technologies (CCICT). IEEE. pp. 157–163. doi:10.1109/CCiCT56684.2022.00039. ISBN 978-1-6654-7224-1. S2CID 252849669.

- Stefan, Deian, Xiaokui Shu, and Danfeng Daphne Yao. "Robustness of keystroke-dynamics based biometrics against synthetic forgeries." computers & security 31.1 (2012): 109-121.

- "Selectric bug".

- "The Security Digest Archives". Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- "Soviet Spies Bugged World's First Electronic Typewriters". qccglobal.com. Archived from the original on 2013-12-20. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- ^ Geoffrey Ingersoll. "Russia Turns To Typewriters To Protect Against Cyber Espionage". 2013.

- ^ Sharon A. Maneki. "Learning from the Enemy: The GUNMAN Project" Archived 2017-12-03 at the Wayback Machine. 2012.

- Agence France-Presse, Associated Press (13 July 2013). "Wanted: 20 electric typewriters for Russia to avoid leaks". inquirer.net.

- Anna Arutunyan. "Russian security agency to buy typewriters to avoid surveillance" Archived 2013-12-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- "What is a Keylogger?". PC Tools.

- Caleb Chen (2017-03-20). "Microsoft Windows 10 has a keylogger enabled by default – here's how to disable it".

- "The Evolution of Malicious IRC Bots" (PDF). Symantec. 2005-11-26. pp. 23–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 15, 2006. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- Jonathan Brossard (2008-09-03). "Bypassing pre-boot authentication passwords by instrumenting the BIOS keyboard buffer (practical low level attacks against x86 pre-boot authentication software)" (PDF). iViz Security. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-13. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- "Web-Based Keylogger Used to Steal Credit Card Data from Popular Sites". Threatpost | The first stop for security news. 2016-10-06. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- "SpyEye Targets Opera, Google Chrome Users". Krebs on Security. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- K.P.H. Sullivan & E. Lindgren (Eds., 2006), Studies in Writing: Vol. 18. Computer Key-Stroke Logging and Writing: Methods and Applications. Oxford: Elsevier.

- V. W. Berninger (Ed., 2012), Past, present, and future contributions of cognitive writing research to cognitive psychology. New York/Sussex: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781848729636

- Vincentas (11 July 2013). "Keystroke Logging in SpyWareLoop.com". Spyware Loop. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Microsoft. "EM_GETLINE Message()". Microsoft. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- "Apple keyboard hack". Digital Society. Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- "Keylogger Removal". SpyReveal Anti Keylogger. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- "Keylogger Removal". SpyReveal Anti Keylogger. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- Jeremy Kirk (2008-12-16). "Tampered Credit Card Terminals". IDG News Service. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- Andrew Kelly (2010-09-10). "Cracking Passwords using Keyboard Acoustics and Language Modeling" (PDF).

- Sarah Young (14 September 2005). "Researchers recover typed text using audio recording of keystrokes". UC Berkeley NewsCenter.

- Knight, Will. "A Year Ago: Cypherpunks publish proof of Tempest". ZDNet.

- Martin Vuagnoux and Sylvain Pasini (2009-06-01). Vuagnoux, Martin; Pasini, Sylvain (eds.). "Compromising Electromagnetic Emanations of Wired and Wireless Keyboards". Proceedings of the 18th Usenix Security Symposium: 1–16.

- "ATM camera". www.snopes.com. 19 January 2004. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- Maggi, Federico; Volpatto, Alberto; Gasparini, Simone; Boracchi, Giacomo; Zanero, Stefano (2011). "A fast eavesdropping attack against touchscreens" (PDF). 2011 7th International Conference on Information Assurance and Security (IAS). 7th International Conference on Information Assurance and Security. IEEE. pp. 320–325. doi:10.1109/ISIAS.2011.6122840. ISBN 978-1-4577-2155-7.

- Marquardt, Philip; Verma, Arunabh; Carter, Henry; Traynor, Patrick (2011). (sp)iPhone: decoding vibrations from nearby keyboards using mobile phone accelerometers. Proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on Computer and communications security. ACM. pp. 561–562. doi:10.1145/2046707.2046771.

- "iPhone Accelerometer Could Spy on Computer Keystrokes". Wired. 19 October 2011. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- Owusu, Emmanuel; Han, Jun; Das, Sauvik; Perrig, Adrian; Zhang, Joy (2012). ACCessory: password inference using accelerometers on smartphones. Proceedings of the Thirteenth Workshop on Mobile Computing Systems and Applications. ACM. doi:10.1145/2162081.2162095.

- Aviv, Adam J.; Sapp, Benjamin; Blaze, Matt; Smith, Jonathan M. (2012). "Practicality of accelerometer side channels on smartphones". Proceedings of the 28th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference on - ACSAC '12. Proceedings of the 28th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference. ACM. p. 41. doi:10.1145/2420950.2420957. ISBN 9781450313124.

- Cai, Liang; Chen, Hao (2011). TouchLogger: inferring keystrokes on touch screen from smartphone motion (PDF). Proceedings of the 6th USENIX conference on Hot topics in security. USENIX. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- Xu, Zhi; Bai, Kun; Zhu, Sencun (2012). TapLogger: inferring user inputs on smartphone touchscreens using on-board motion sensors. Proceedings of the fifth ACM conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks. ACM. pp. 113–124. doi:10.1145/2185448.2185465.

- Miluzzo, Emiliano; Varshavsky, Alexander; Balakrishnan, Suhrid; Choudhury, Romit Roy (2012). Tapprints: your finger taps have fingerprints. Proceedings of the 10th international conference on Mobile systems, applications, and services. ACM. pp. 323–336. doi:10.1145/2307636.2307666.

- Spreitzer, Raphael (2014). PIN Skimming: Exploiting the Ambient-Light Sensor in Mobile Devices. Proceedings of the 4th ACM Workshop on Security and Privacy in Smartphones & Mobile Devices. ACM. pp. 51–62. arXiv:1405.3760. doi:10.1145/2666620.2666622.

- Hameiri, Paz (2019). "Body Keylogging". Hakin9 IT Security Magazine. 14 (7): 79–94.

- Young, Adam; Yung, Moti (1997). "Deniable password snatching: On the possibility of evasive electronic espionage". Proceedings. 1997 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (Cat. No.97CB36097). pp. 224–235. doi:10.1109/SECPRI.1997.601339. ISBN 978-0-8186-7828-8. S2CID 14768587.

- Young, Adam; Yung, Moti (1996). "Cryptovirology: Extortion-based security threats and countermeasures". Proceedings 1996 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. pp. 129–140. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.44.9122. doi:10.1109/SECPRI.1996.502676. ISBN 978-0-8186-7417-4. S2CID 12179472.

- John Leyden (2000-12-06). "Mafia trial to test FBI spying tactics: Keystroke logging used to spy on mob suspect using PGP". The Register. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- John Leyden (2002-08-16). "Russians accuse FBI Agent of Hacking". The Register.

- Alex Stim (2015-10-28). "3 methods to disable Windows 10 built-in Spy Keylogger".

- "What is Anti Keylogger?". 23 August 2018.

- Creutzburg, Reiner (2017-01-29). "The strange world of keyloggers - an overview, Part I". Electronic Imaging. 2017 (6): 139–148. doi:10.2352/ISSN.2470-1173.2017.6.MOBMU-313.

- Goring, Stuart P.; Rabaiotti, Joseph R.; Jones, Antonia J. (2007-09-01). "Anti-keylogging measures for secure Internet login: An example of the law of unintended consequences". Computers & Security. 26 (6): 421–426. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2007.05.003. ISSN 0167-4048.

- Austin Modine (2008-10-10). "Organized crime tampers with European card swipe devices". The Register. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- Scott Dunn (2009-09-10). "Prevent keyloggers from grabbing your passwords". Windows Secrets. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- Christopher Ciabarra (2009-06-10). "Anti Keylogger". Networkintercept.com. Archived from the original on 2010-06-26.

- Cormac Herley and Dinei Florencio (2006-02-06). "How To Login From an Internet Cafe Without Worrying About Keyloggers" (PDF). Microsoft Research. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

External links

[REDACTED] Media related to Keystroke logging at Wikimedia Commons

| Malware topics | |

|---|---|

| Infectious malware | |

| Concealment | |

| Malware for profit | |

| By operating system | |

| Protection | |

| Countermeasures | |