Title page of La Silva Curiosa Title page of La Silva Curiosa | |

| Author | Julián Íñiguez de Medrano |

|---|---|

| Original title | La Silva Curiosa |

| Language | Spanish |

| Subject | Renaissance miscellany |

| Genre | Non-fiction, anthology |

| Published | Paris |

| Publisher | Nicolas Chesneau |

| Publication date | 1583 |

| Publication place | Kingdom of France |

| Media type | |

| This is the first volume of seven, however only the first was ever published. | |

La Silva Curiosa (English: The Curious Forest, French: La Silva Curieuse) is a Renaissance miscellany by Julián Íñiguez de Medrano, a poet, playwright, author and Navarrese knight, dedicated to Queen Margaret of Valois. First published by Nicolas Chesneau in 1583, Paris, Medrano divided it into seven books due to the diverse subject matter. He was in Fontainebleau when Queen Margaret of Valois commanded him to compose a book of Spanish emblems and mottoes and some other work in the Spanish language on various and curious subjects. Julián Íñiguez de Medrano spent hours in Saint Maur and in Bois de Vincennes, composing La Silva Curiosa.

Publications

The full title of his book is "La Sylva Curiosa de Julián de Medrano, Caballero Navarrese, which deals with various very subtle and curious things, very appropriate for Ladies and Gentlemen in all virtuous and honest conversations. Addressed to the very high and most serene Queen of Navarre su Sennora, in Paris, Printed at the House of Nicolas Chesneav, MDLXXXIII." published in 1583 by Nicolas Chesneau and edited by Mercedes Alcalá Galán. Until the end of the 18th century, the edition that should be considered the "princeps," the one from Paris, published by Nicolás Chezneau (and not the clearly pirated edition from Zaragoza, published by Joan Escartilla in 1580), remained unknown.

Second edition (1608)

A version of Julian Iñiguez de Medrano's La Silva Curiosa, originally published in 1583, was republished in Paris in 1608. This edition, "corrected in this new edition and improved for readability by César Oudin," introduced a notable addition: Cervantes's "Novela del curioso impertinente" (Novel of the Curious Impertinent), incorporated without attribution to the author. This inclusion sparked speculation, with some attributing the short story to Medrano. The 1608 edition holds significance for Cervantes collectors and scholars as it features an early printing of his Novela del Curioso Impertinente, a narrative later recounted in Don Quixote and first published in 1605. This story concludes La Silva Curiosa, commencing on page 274.

Of note, two copies of both editions can be found in the "Rares" section of the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid. At the time of the publication of his work, Medrano would have been approximately sixty-three years old. Additionally, Nicolas Chesneau, a prominent Catholic printer known for anti-Huguenot propaganda, undertook the publication of La Silva Curiosa.

Background

In 1582, Julian Iñiguez de Medrano found himself in the vicinity of the capital, specifically in Fontainebleau, where he commenced the composition of his work at the behest of the queen. Subsequently, he concluded his writing in the Bois de Vincennes. The authenticity of this information is supported by documents pertaining to the court of Marguerite de Valois, meticulously gathered by Philippe Lauzun. According to explicit statements within the work, Medrano's motivation was not primarily to instruct in the language but rather because the queen had "commanded him to compose a book on Spanish companies and currencies, and some other work in Spanish," encompassing diverse and intriguing subjects. The queen, having a penchant for the Spanish language but experiencing vexation in reading it, sought amusement. Queen Margaret, as attested by Pierre de Bourdeille, Lord of Brantôme, possessed a proficiency in Spanish and Italian as if she had been nurtured and immersed in Italy and Spain throughout her life.

The Curious Forest

In the beginning of La Silva Curiosa, Medrano addresses the reader directly with two octaves:

Here, the keen mind may find a way to lighten the heaviest, dreariest hours, to pass the time in joy and in play, in this garden of sweet and delightful flowers. Here one may behold divine things, indeed, a keen, lofty style, grave and resounding, words of love, in folly and reason, and twenty thousand secrets of nature surrounding.

You who traverse the mountain of Love, seeking curious inventions and delights, enter this forest and, resting within, you will savor two thousand sights. Within, you’ll gather diverse blooms, if you choose to wander these ways, and enchanting away your sorrows and pains, you will forget your troubles and dismay.

According to Mercedes Alcalá Galán (1998: 10-11):

embodies all the generic principles applicable to miscellanies and is particularly notable for its wholly literary and fictional content. The use of the garden metaphor, with its diverse flowers symbolizing a miscellany, reflects an intent for entertainment and a certain freedom in composition, suggesting an improvisational approach to writing.

Testimony of de la Morinière

ABOUT THE CURIOUS FOREST OF DE MEDRANE: Let whoever wishes boast about Apelles, Zeuxis, Lisippus, and those closer to our time, Raphael, Michelangelo, and so many experts in their proportions, shading, and variegation. As for me, I value more the tableau of nature, of manners, of teachings, and of the entire universe, which MEDRANE encloses in his beautiful verses, taking the name and figure from a forest. Their portraits only affect our eyes, and hold our idle minds suspended, perishable otherwise and of no memory. But this speaking tableau is much better adorned and cannot be stifled by time in this way, engraving its beautiful art and glory in minds.

Testimony of Jean Daurat, the Royal Poet

What various peoples and various cities, the great man of former days, an Ithacan, had seen. But still, he brought nothing back to his paternal home: While plundering others, he robs the sea of its riches. Until, at last, he reached the welcoming company of Alcinous: From there, the guest brought back various treasures to his home. Behold, a new Ulysses, like Julius Medrano, From various peoples, from diverse seas, He brings back every kind of gem and every kind of gold: A treasure as great as that of Ulysses, never before seen.

Summary

The Silva Curiosa is a diverse compilation of epitaphs, pastoral poetry, proverbs, and narratives featuring necromancers and ghosts. Within this heteroclite miscellany, Medrano assembles a collection of engaging curiosities. La Silva Curiosa encompasses a wide array of materials, including sayings, sentences, stories, phrases, nicknames, assorted anecdotes, notable quotes from authorities across various subjects, as well as poetic compositions, love stories, and exotic adventures. The work exhibits a deliberate motley disorder, as implied by the very title of Silva.

It cites well-known authors and others who are not so much so: "Antonio Miraldo, Alifarnes, Avicenna, Aristotle, Aeliano, Amato Lusitano, Andrea Matheolo, Fray Alonso del Castillo, St. Augustine, Democritus, Dioscorides, Galen, Plutarch, Peter Messiah, Ptolemy, St. Thomas, but not in others because he is usually a liar, Albert the Great in certain steps, but not in all because he says so much nonsense and lies, Sant Cristobal Navarre, great philosopher and astrologer, the Hermit of Salamanca, very rare in secrets and experiences, above all the friars and hermits of his time, and in the Secrets of Nature very speculative, curious and excellent."

Julian's additional objective comes to light, focused on unraveling the mysteries of nature linked to the persona of the Salamanca hermit. Proficient in wielding and leveraging these secrets to his benefit, Julian imparts this knowledge to his disciples. A juxtaposition emerges between Julian and another character, Cristóbal, who similarly commands the secrets of nature. However, in Cristóbal's case, the perspective takes a darker turn, delving into the realm of necromancy.

Within Medrano's work, "La Silva Curiosa," a precursor to the iconic character Freddy Krueger can be discerned. The narrative unfolds with a German knight entering a diabolical pact, facilitated by a necromancer who, at the culmination of the incantations, is seized by demons. The malevolent necromancer subsequently haunts the knight's dreams, guiding him through a realm of nightmares and ultimately transporting him to the afterlife with eerie screams. This unsettling narrative is just one among several macabre and paranormal episodes found in this section of the work. Notable instances include the accounts of the witch Orcavella and a hermitage famulus who divulges forbidden book secrets and the manipulation of a magic mirror. The famulus possesses the ability to enchant wolves and ravens, conjure ducks, foxes, and badgers, induce hail, and even heal livestock. Woven into the broader narrative, the protagonist Julián Íñiguez de Medrano ("Julio") embarks on a journey from Roncesvalles to the Indies, albeit the details of this segment remain untold. The journey encompasses pilgrimages to Santiago de Compostela and Finisterre, Medrano intricately interlaces tales and compositions, presenting them to Queen Margarita and the inquisitive reader.

Volumes

The 7 books of La Silva Curiosa

The first book of La Silva curiosa ("The Curious Forest"), the only one still readable, is a set of letters, mottoes, sayings, proverbs, moral sentences, verses... Within this, is the "curious vergel" – this is how Medrano defines his work – various "such senses, sharp answers and very funny and recreational tales, with some curious epitaphs." These stories to which Julián Íñiguez de Medrano refers are called anecdotes, jokes, or chascarrillos (stories of few lines; some take up, exceptionally, a little more than a page or a page and a half). The secrets of nature have a presence in the work. Medrano intended to record these secrets in the seventh book of La Silva Curiosa. Furthermore, for the remaining six books, all of them in some way deal with the properties or secrets of nature:

- The second book deals with the nature of herbs and plants and their rarest, proven, and true virtues.

- The third book discusses the properties and virtues of precious stones and the benefits that can be derived from them, chosen through experience.

- The fourth book teaches the properties, nature, and virtues of many terrestrial animals and reveals many proven secrets obtained from them.

- The fifth book focuses on the properties and nature of fish and the benefits derived from them.

- The sixth book delves into the nature, virtues, and benefits of celestial and terrestrial birds, along with many proven and miraculous secrets.

- The seventh book deals with the secrets of nature.

Content

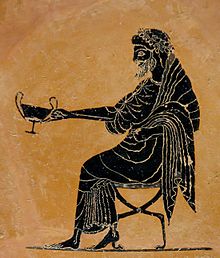

The pages of this work accumulate enigmas, proverbs, games, and natural observations from antiquity, presenting a collection of examples. Palindromes, such as "To the only Rome, Love to los solos sola," enigmas like the intricate one involving a eunuch striking a bat on an elder tree with a rough stone, and goliardic parodies, including a humorous prayer to Bacchus ("Potemus. Oh valde potens, oh fortissime Bacche... Per eundem Bachum qui bibit et potat per pocula poculorum"), adorn these pages. Additionally, the compilation features short stories, some of which are borrowed from Timoneda or Juan Aragonés. Julian Iñiguez de Medrano exhibits a particular fondness for epitaphs, amassing a diverse array in Spanish, French, and Latin. Many of these epitaphs carry a burlesque tone, exemplified by the one for poor Joan Vitulli, a seventeen-year-old boy, written with a touch of reluctance.

Narrratives

One of Julián Íñiguez de Medrano's short-length narrative pieces in La Silva Curiosa inspired Lope de Vega, as has been highlighted by critics: Julián Íñiguez de Medrano's comedy "Lo que ha de ser" is about two men who speak ill of women and promise never to marry; however, one of them falls in love and marries a widow, despite rumours about his bad reputation; at the end, the account ends with the indication that he too falls in love with a widow. He was deceived.

Another, entitled "How funny," reads as follows: “A Wise man saw that all the people of his homeland were in the rain in the country, and the village alone, he also went out, saying, "I would rather be mad with everyone than wise alone."

The narrative titled "Velasquillo's Graceful Revenge, with Three Knights" recounts the tale of three knights purchasing a trout and extending an invitation to a buffoon to join them for a meal. The peculiar dining ritual involves breaking the trout into pieces, and each participant, in their pursuit of a portion, must recite a Bible passage related to the chosen part. One knight claims the head, another the middle, and the third the tail, each citing the corresponding biblical verses. Consequently, Velasquillo is left with only the garlic sauce. Seeking retribution, he humorously sprays the three knights, delivering festive comments in Macaronic Latin: "Aspergues dominates me. Hyssop."

Other examples in La Silva Curiosa

- A poem entitled "The graceful simplicity of a Biscayno" (as there is no executioner in the village, they pay the Biscayan a ducat for hanging an evildoer, and they also give him his clothes; the simple one says that he will hang the entire population, even if they pay him only half a ducat per person);

- A poem entitled "of a painter having erred the work". (the painter portrays the Lord's Supper with thirteen apostles, and to disguise his error he puts one in a postcard; when he is made to see the ruling, he excuses himself by saying that the mail will not "but supper and part").

- A poem entitled "Consolation of a man as they were whipping a thief, and the excutioner was begged not to give so much to one part, but to move when he struck, the excutioner replied: "Shut up, brother, and everything will go away".

- On page 250 of the Silva begins the "Part of the curious epitaphs found."

- A poem entitled "By July in various lands, sent to the wise brave Marfisa, in the same natural languages in which they were composed." (Medrano transcribes and goes on counting where he located them, sometimes with a small history relating to the discovery or the containment of the epitaph in question).

- Julian Iñiguez de Medrano also recounts his encounter with a hermit on the Way of Santiago in the story of the "Indian hermit,"

- A poem entitled "The charming Orcavella"

Poems or Sonnets in Medrano's La Sylva Curiosa

- A Sonnet “to the most serene Reyna su Señora etando en Nerac” dedicated to Queen Margaret of Valois

- A "Sonnet composed in the voice and response called echo"

- A sonnet "To the beautiful shepherdess called Pandora"

- A sonnet by Julián de Medrano on the motto "Who resists Love when angry?"

- "Cruel extremes of love for the beautiful Pandora", which is part of the section "Pastoral verses by Julio M. heartfelt and very funny"

- A sonnet "To the beautiful shepherdess called Constanza"

- A Poem titled "Of a shepherd in love with a very ugly shepherdess"

- A poem titled "Julian Medrano, in praise of women"

- "Pastoral Verses by Julio M., Sentimental and Quite Humorous." found in the first part of "La silva curiosa"

The book ends with some laudatory poems and other postliminary texts: "To the most invincible and powerful Caesar Henry III, King of France and Poland, Julius Medrano, Navarrese"; a few verses in Latin: "Ivlius de Medrano, in Lectorem Zoïlum"; the "Prophecy of the Cave of Salamanca for the present year, and then usque ad finem seculi," etc. The colophon is: "Deo volente, navigabo vimine. / O. DE. EC. SE. AS. ME. /End of this Silva's first book."

'In praise of women' by Julian Iniguez de Medrano

'In praise of women' is a poem found in the first book of La Silva Curiosa first published in 1583. Julián Íñiguez de Medrano explains himself that he is "returning to women, and desiring that they may know the great reverence with which I hold the name of woman, and that, leaving the path of ungrateful and harmful slanderers, I strive to elevate and praise this creature to the highest heaven (since nature in its generation made her so noble, and among all creatures, she emerged so perfect) in return for the many obligations we men owe them, as we are born of them, die without them, live in them, and we couldn't preserve or endure without them. As a token of the pure and natural affection I have for them, I offer them the following verses," which he composed in their favor and in praise of them:

When God created everything and formed man first, you can see that, as for a rough one, He made him from pure mud. But for Eve, as a testimony and proof that we should prefer her, He took her from the rib by subtle and new work. And He commanded that the man He had created in this way should forsake father and mother and join with the woman whom He gave to him as a companion, singularly. Commanding him to guard her as his very own self, as a mirror and a crown in which he should look. Without women, this world would lack pleasures and joy, and it would be like a fair without merchants. Life would be tasteless without them, a people in confusion, a body without a heart, a wandering soul in the wind. Reason without understanding, a tree without fruit or flower, a whip without a master, and a house without a foundation. What are we worth? What are we? What do we deserve? If women were to fail us, to whom would the purpose of what we do and think be directed? Who is the cause that we become partakers of love, which is the sweetest taste that we enjoy in this life? Who would take charge of the household and the particular account of the house and the home, and the estate and the farming? We have their comfort, so certain, so without doubt, in our adversities, hardships, and illnesses on this earth. From them flows all the good that man gains, and they are its glory, the guardians, firmness, and seal of our human nature.

The Enchantress Orcavelle

Julian Iñiguez de Medrano's Greek Manuscript is revealed through the discovery of what is presented as a translation into French of a manuscript found by Louis Adrien Du Perron De Castera in the Abbey of Châtillon (sister-house of Trois-Fontaines Abbey). The National Library of Paris holds a small work in whose exact title is as follows: "RELATION OF THE DISCOVERY OF THE TOMB OF THE ENCHANTRESS ORCAVELLE WITH THE TRAGIC HISTORY OF HER LOVES. Translated from the Spanish of Jule Iniguez de Médrane. IN PARIS, Rue de la Harpe, At the Widow HOURY's, opposite Rue S. Severin, at St. Esprit. MDCCXXIX With Approval & Permission. pp.7".

According to Eva Lara Alberola, in 1729, Relation de la découverte du tombeau de l'enchanteresse Orcavelle was published in Paris, attributed to Julián Íñiguez de Medrano and translated by Louis Adrien Du Perron De Castera. However, the text diverges from Medrano’s Silva Curiosa (1583), and it is likely that De Castera himself authored it, drawing on Medrano’s work as well as Luis Barahona de Soto's Las lágrimas de Angélica (1586). Alberola—at the Catholic University of Valencia—questions De Castera's originality of the Relation and its connections to earlier Spanish sources, particularly in its portrayal of witches and ogresses.

Lara Alberola argues that De Castera's Relation transforms Orcavella into a Gothic antihero and heightens horror elements, making her a supernatural figure depicted through her own voice. Alberola believes that the adaptation shifts from Medrano’s detached storytelling in the Silva Curiosa, where Orcavella’s tale was relayed by a Galician shepherd, to an introspective Gothic style. She asserts that by claiming to translate a “lost manuscript,” De Castera may have used a narrative device to add mystery and authenticity, positioning the Relation as a precursor to Gothic fiction.

Testimony from Louis Adrien Du Perron De Castera

The author of this translation, Louis Adrien Du Perron De Castera, after dedicating it "To His Highness Monseigneur de Bouillon de la Tour d'Auvergne, Grand Chamberlain of France, Governor, and Lieutenant General of the Upper and Lower Regions and the Province of Auvergne, Commander of the Turenne Regiment," then goes on to explain the reasons justifying his translation work:

It is not the itch to be seen as an author that compels me to bring this little work to light; I have merely faithfully translated it from the Spanish of Julian Iniguez de Médrano. If there are some noteworthy features found in it, the glory is solely due to him. He flourished in the time of Queen Marguerite of Navarre, and this Princess, who knew how to value people of wit, believed she gained much by having him at her Court, where he was for several years both an ornament and a delight.

Furthermore, he provides interesting but difficult-to-verify information about Medrano's works: "He has two books to his name, with the titles 'Verger fertile' and 'Fóret curieuse,' both of which have had various editions, followed by general acclaim both in France and Spain". With this, it appears to confirm that Medrano carried out his project of writing his "Vergel curioso," to which he might have given the title "Vergel fértil," if at least De Castera's translation is faithful. The following clarification by de Castera states: "The latter has never been printed; I found the manuscript written by Médrane himself in the illustrious Abbey of Châtillon, where, in the intervals of leisure that more serious studies allowed me, I amused myself by adapting it in a French manner." Adrien Du Perron De Castera supposedly relied on nothing less than an autographed manuscript by Medrano. the translator's remarks leave no doubt about his sincerity, as he emphasizes his role as a translator, even expressing doubts about the truth of Medrano's account after comparing this new story of Orcavella with the one already featured in Medrano's original. Médrano himself presents his original work as an absolute truth and asserts that in Colchis, presently called Mingrelia, he actually discovered the Tomb of the Enchantress Orcavella. Castera becomes the narrator of the events that happened to Medrano, who is thus described in the third person:

Jule Iniguez de Médrano, a Navarrese gentleman, illustrious for his knowledge and celebrated for his travels throughout almost the entire world, recounts that one day, while sitting near Mount Caucasus on a grassy hill, he felt that the grass beneath him was sinking. He moved it aside and saw that it covered a hole the width of a man's body. This hole led to a staircase carved into the rock. Naturally curious, Médrano imagined that it might be an underground passage that perhaps contained some rarity or treasure, and he resolved to descend. To do so, he went to fetch a lantern and, accompanied by a faithful servant, he soon returned to the exact spot he had noticed.

This type of narration continues until the account of Medrano's discovery of a Greek manuscript. This manuscript, which according to De Castera, Medrano claims to have found in a tomb, and contains a confession, in the first person, of a witch named Orcavella, who, after briefly evoking her life as a fat collector, ogress, and vampire, relates the sad story of her love. From there, it could be a faithful translation of Medrano's text, as what precedes clearly corresponds to an account attributable to De Castera, drawing inspiration from the manuscript found in the Abbey of Châtillon and elements from the second part of the Silva Curiosa. Historians compared this introductory narrative with the data contained in the miscellany, and found that it coincides with some elements in the introductory sections of the Silva and in the account of the journey to Santiago.

Dedication to Queen Margaret of Valois

It was Queen Margaret of Valois, eager to read texts in Spanish that commissioned Medrano to write La silva curiosa, the work that she would pass on to posterity. Julian dedicated the Silva Curiosa to Queen Marguerite de Navarre, as indicated in his prologue:

"To the most serene QUEEN, HER LADYSHIP. Just as the good gardener, after patiently enduring the cruel cold of winter (and often toiling amidst the snow and harsh ice, consoled only by the hope that one day he will savor the flowers and delicious fruit promised by nature in reward for his tireless labor in tending to his garden), and one day, at the beginning of spring, while digging and tilling among thorns and vexing weeds, uncovers in a corner a blooming rose, he receives such a stroke of good fortune and immense joy that, forgetting past toils, he tosses his spade to the ground, rushes to seize it, and, with great delight, kisses it and blesses the Lord who created it. He then stops, and while in doubt, ponders who deserves to enjoy this new flower, the harbinger of sweet spring.

In his rustic thoughts, he concludes that only one person is worthy of it, the Lord who gave him the land for his garden, where the rose was born. Therefore, with a heart free from ingratitude, he departs, filled with happiness, and upon reaching the presence of that Lord, he joyfully offers the humble gift. In a similar way, I, Most High and Serene Lady (being a native of Navarre and recognizing that the greater part of the honor, being, and fortune I possess, next to God, springs and proceeds from Your Majesty as the true source of my happiness and life), have found this first and tender flower of my labors among the thorns of my sorrows and toils. I removed it from among them, and not knowing anyone who deserves it as much, nor to whom I owe it, I present it to Your Majesty.

Though this gift may be small, the giver's spirit is great, and I will strive in the future to create something of greater value than this work, which I have divided into seven books due to their diverse subject matter. In this first book, Your Majesty will find various enjoyable subjects. Although the topics in this book are intriguing, I beseech Your Majesty not to stop here but to invest some time in the other six books that follow, written in prose. If in this first book Your Majesty enjoys the flowers, in the subsequent ones, you will savor the delicious fruit of the rarest and most curious secrets of nature that I have been able to learn and gather from Spain, the Indies, and my interactions with Italians and Portuguese. Since I have discovered and acquired them with curiosity and labor, I have no doubt that Your Majesty, recognizing my goodwill, will favor them with your attention. And if it were not for what Your Majesty told me while I was in Fontainebleau, when you commanded me to compose a book of Spanish emblems and mottoes and some other work in the Spanish language on various and curious subjects, I would not dare to offer this Silva to Your Majesty, as it is unworthy of such value and merit.

However, ultimately desiring to conform to your wishes in all things and finding nothing difficult or laborious for your service, and recognizing that Your Majesty naturally takes pleasure in diverse and curious matters and greatly enjoys reading the Spanish language, I spent all the hours this past summer at Saint Maur and in the Bois de Vincennes, which I could honestly divert from serving Your Majesty, in composing this Silva. In it, I have only endeavored to include things that I believe will be entertaining and delightful to Your Majesty, without venturing into the vast ocean of Your Majesty's virtues, gifts, and graces to praise and extol them, as I know that such an endeavor would be as challenging and laborious as attempting to count the leaves of Mount Olympus or the stars in the Empyrean. Some may ask why, given that the discourse of my Silva begins with pastoral verses and other poetic elements, I did not choose such a substantial and excellent subject as the rare gifts of Your Majesty. In response to them, I say that my vessel is too small to sail in such a vast sea. For I recognize that my language is inept, my style coarse, and my intellect feeble and extremely weak to praise a soul as beautiful and divine (enclosed in a body endowed with so many gifts of nature) as Your Majesty.

Therefore, even though this offering of mine is humble, I implore Your Majesty to show me the same kindness as King Alfonso of Aragon did to a poor farmer. This farmer, upon finding a most splendid radish on his land, larger than any that had ever been seen in that region, thought to himself that no one, apart from the King, deserved to eat something so beautiful. With great joy, he wrapped the radish in the folds of his coat and presented it to the King. The King, delighted to see the sincere goodwill of the poor farmer, commended it highly and accepted the humble gift with great pleasure, expressing his infinite gratitude, bestowing favors, and holding the farmer dear for the rest of his life. May my Silva be as fortunate as that radish! Because beyond the contentment, well-being, and favor I would receive from it, this reward would give me the courage and heart to undertake more lofty and serious works to offer to Your Majesty. Though this work may not deserve to reach even the lowest of Your Majesty's merits, I still hope it will be well-received, both because of its virtuous, honest, and curious subject matter, composed in good Spanish, and because of the natural and pure intention with which it has been dedicated to Your Majesty.

Under Your protection and favor, I hope this humble book (and another work I am preparing and reserving for Your Majesty) will come to light and be secure, without fear of the judgments of critics and envious individuals who always criticize and mock everything they see and read. I seek no greater good in this life than the one I hope to obtain whenever it pleases Your Majesty to accept my service and find it pleasing. I conclude, praying for the health of Your Majesty, whose life, honor, and status may God Our Lord guard and increase for many years with all happiness and peace. From this Hermitage in the Bois de Vincennes, on this day of Saint Paul, the twenty-fifth of January, in the year 1583. I kiss the Royal feet of Your Majesty, your most obedient servant, vassal, and subject, Julio Iñiguez de Medrano."

References

- ^ Julián de Medrano, José María Sbarbi y Osuna (1878). La Silva curiosa (in Spanish). University of Michigan. A. Gomez Fuentenebro.

- ^ Medrano, Julian Iniguez de (1608). La silva curiosa, en que se tratan diversas cosas sotilissimas ... (in Spanish). Orry.

- ^ Indurain, Carlos Mata. "Julián Íñiguez de Medrano, su Silva curiosa (1583) y una anécdota tudelana". Academia.

- "CVC. Fortuna de España. Literatura". cvc.cervantes.es. Retrieved 2025-01-12.

- https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/4221694.pdf

- La Sylva Curiosa pp. 103–106

- La Sylva Curiosa (p. 193)

- La Sylva Curiosa (pp. 201- 202)

- La Sylva Curiosa pp. 206–207

- La Sylva Curiosa (p. 211)

- La Sylva Curiosa (p. 209)

- La Sylva Curiosa pp. 285–390

- insulabaranaria (2015-09-16). "Un "Soneto compuesto en la voz y respuesta llamada eco" de Julián de Medrano". Ínsula Barañaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- insulabaranaria (2015-09-14). "El soneto "A la hermosa pastora llamada Pandora" de Julián de Medrano". Ínsula Barañaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- insulabaranaria (2015-09-03). "El soneto "Crueles extremos de amor a la hermosa Pandora" de Julián de Medrano". Ínsula Barañaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- insulabaranaria (2015-09-02). "El soneto "A la hermosa pastora llamada Constanza" incluido en "La Silva curiosa de Julián de Medrano"". Ínsula Barañaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- insulabaranaria (2015-09-01). "Las coplas "De un pastor enamorado de una pastora muy fea", de Julián de Medrano". Ínsula Barañaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- insulabaranaria (2015-09-10). "El poema «Julio Medrano en alabanza de las mujeres» («La silva curiosa de Julián de Medrano», 1583)". Ínsula Barañaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- La Sylva Curiosa p. 169

- insulabaranaria (2015-09-10). "El poema «Julio Medrano en alabanza de las mujeres» («La silva curiosa de Julián de Medrano», 1583)". Ínsula Barañaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- Román d'Amat, Dictionnaire de biographie francaise, Paris, Letouzey, 1970.

- ^ Lara Alberola, Eva (2017-06-26). "Orcavella francesa del siglo XVIII: entre la «Silva curiosa» de Medrano y «Las lágrimas de Angélica» de Barahona de Soto". Castilla. Estudios de Literatura (8): 178–215. doi:10.24197/cel.8.2017.178-215. hdl:20.500.12466/2470. ISSN 1989-7383.

- "La Silva curiosa". A. Gomez Fuentenebro. 1878.

| This article needs additional or more specific categories. Please help out by adding categories to it so that it can be listed with similar articles. (February 2024) |