Ambiguity is the type of meaning in which a phrase, statement, or resolution is not explicitly defined, making for several interpretations; others describe it as a concept or statement that has no real reference. A common aspect of ambiguity is uncertainty. It is thus an attribute of any idea or statement whose intended meaning cannot be definitively resolved, according to a rule or process with a finite number of steps. (The prefix ambi- reflects the idea of "two", as in "two meanings").

The concept of ambiguity is generally contrasted with vagueness. In ambiguity, specific and distinct interpretations are permitted (although some may not be immediately obvious), whereas with vague information it is difficult to form any interpretation at the desired level of specificity.

Linguistic forms

Lexical ambiguity is contrasted with semantic ambiguity. The former represents a choice between a finite number of known and meaningful context-dependent interpretations. The latter represents a choice between any number of possible interpretations, none of which may have a standard agreed-upon meaning. This form of ambiguity is closely related to vagueness.

Ambiguity in human language is argued to reflect principles of efficient communication. Languages that communicate efficiently will avoid sending information that is redundant with information provided in the context. This can be shown mathematically to result in a system that is ambiguous when context is neglected. In this way, ambiguity is viewed as a generally useful feature of a linguistic system.

Linguistic ambiguity can be a problem in law, because the interpretation of written documents and oral agreements is often of paramount importance.

Pepe vio a Pablo enfurecido.

Interpretation 1: When Pepe was angry, then he saw Pablo.

Interpretation 2: Pepe saw that Pablo was angry.

Here, the syntactic tree in figure represents interpretation 2.

Lexical ambiguity

The lexical ambiguity of a word or phrase applies to it having more than one meaning in the language to which the word belongs. "Meaning" here refers to whatever should be represented by a good dictionary. For instance, the word "bank" has several distinct lexical definitions, including "financial institution" and "edge of a river". Or consider "apothecary". One could say "I bought herbs from the apothecary". This could mean one actually spoke to the apothecary (pharmacist) or went to the apothecary (pharmacy).

The context in which an ambiguous word is used often makes it clearer which of the meanings is intended. If, for instance, someone says "I put $100 in the bank", most people would not think someone used a shovel to dig in the mud. However, some linguistic contexts do not provide sufficient information to make a used word clearer.

Lexical ambiguity can be addressed by algorithmic methods that automatically associate the appropriate meaning with a word in context, a task referred to as word-sense disambiguation.

The use of multi-defined words requires the author or speaker to clarify their context, and sometimes elaborate on their specific intended meaning (in which case, a less ambiguous term should have been used). The goal of clear concise communication is that the receiver(s) have no misunderstanding about what was meant to be conveyed. An exception to this could include a politician whose "weasel words" and obfuscation are necessary to gain support from multiple constituents with mutually exclusive conflicting desires from his or her candidate of choice. Ambiguity is a powerful tool of political science.

More problematic are words whose multiple meanings express closely related concepts. "Good", for example, can mean "useful" or "functional" (That's a good hammer), "exemplary" (She's a good student), "pleasing" (This is good soup), "moral" (a good person versus the lesson to be learned from a story), "righteous", etc. "I have a good daughter" is not clear about which sense is intended. The various ways to apply prefixes and suffixes can also create ambiguity ("unlockable" can mean "capable of being opened" or "impossible to lock").

Semantic and syntactic ambiguity

Semantic ambiguity occurs when a word, phrase or sentence, taken out of context, has more than one interpretation. In "We saw her duck" (example due to Richard Nordquist), the words "her duck" can refer either

- to the person's bird (the noun "duck", modified by the possessive pronoun "her"), or

- to a motion she made (the verb "duck", the subject of which is the objective pronoun "her", object of the verb "saw").

Syntactic ambiguity arises when a sentence can have two (or more) different meanings because of the structure of the sentence—its syntax. This is often due to a modifying expression, such as a prepositional phrase, the application of which is unclear. "He ate the cookies on the couch", for example, could mean that he ate those cookies that were on the couch (as opposed to those that were on the table), or it could mean that he was sitting on the couch when he ate the cookies. "To get in, you will need an entrance fee of $10 or your voucher and your drivers' license." This could mean that you need EITHER ten dollars OR BOTH your voucher and your license. Or it could mean that you need your license AND you need EITHER ten dollars OR a voucher. Only rewriting the sentence, or placing appropriate punctuation can resolve a syntactic ambiguity. For the notion of, and theoretic results about, syntactic ambiguity in artificial, formal languages (such as computer programming languages), see Ambiguous grammar.

Usually, semantic and syntactic ambiguity go hand in hand. The sentence "We saw her duck" is also syntactically ambiguous. Conversely, a sentence like "He ate the cookies on the couch" is also semantically ambiguous. Rarely, but occasionally, the different parsings of a syntactically ambiguous phrase result in the same meaning. For example, the command "Cook, cook!" can be parsed as "Cook (noun used as vocative), cook (imperative verb form)!", but also as "Cook (imperative verb form), cook (noun used as vocative)!". It is more common that a syntactically unambiguous phrase has a semantic ambiguity; for example, the lexical ambiguity in "Your boss is a funny man" is purely semantic, leading to the response "Funny ha-ha or funny peculiar?"

Spoken language can contain many more types of ambiguities that are called phonological ambiguities, where there is more than one way to compose a set of sounds into words. For example, "ice cream" and "I scream". Such ambiguity is generally resolved according to the context. A mishearing of such, based on incorrectly resolved ambiguity, is called a mondegreen.

Philosophy

Philosophers (and other users of logic) spend a lot of time and effort searching for and removing (or intentionally adding) ambiguity in arguments because it can lead to incorrect conclusions and can be used to deliberately conceal bad arguments. For example, a politician might say, "I oppose taxes which hinder economic growth", an example of a glittering generality. Some will think they oppose taxes in general because they hinder economic growth. Others may think they oppose only those taxes that they believe will hinder economic growth. In writing, the sentence can be rewritten to reduce possible misinterpretation, either by adding a comma after "taxes" (to convey the first sense) or by changing "which" to "that" (to convey the second sense) or by rewriting it in other ways. The devious politician hopes that each constituent will interpret the statement in the most desirable way, and think the politician supports everyone's opinion. However, the opposite can also be true—an opponent can turn a positive statement into a bad one if the speaker uses ambiguity (intentionally or not). The logical fallacies of amphiboly and equivocation rely heavily on the use of ambiguous words and phrases.

In continental philosophy (particularly phenomenology and existentialism), there is much greater tolerance of ambiguity, as it is generally seen as an integral part of the human condition. Martin Heidegger argued that the relation between the subject and object is ambiguous, as is the relation of mind and body, and part and whole. In Heidegger's phenomenology, Dasein is always in a meaningful world, but there is always an underlying background for every instance of signification. Thus, although some things may be certain, they have little to do with Dasein's sense of care and existential anxiety, e.g., in the face of death. In calling his work Being and Nothingness an "essay in phenomenological ontology" Jean-Paul Sartre follows Heidegger in defining the human essence as ambiguous, or relating fundamentally to such ambiguity. Simone de Beauvoir tries to base an ethics on Heidegger's and Sartre's writings (The Ethics of Ambiguity), where she highlights the need to grapple with ambiguity: "as long as there have been philosophers and they have thought, most of them have tried to mask it ... And the ethics which they have proposed to their disciples has always pursued the same goal. It has been a matter of eliminating the ambiguity by making oneself pure inwardness or pure externality, by escaping from the sensible world or being engulfed by it, by yielding to eternity or enclosing oneself in the pure moment." Ethics cannot be based on the authoritative certainty given by mathematics and logic, or prescribed directly from the empirical findings of science. She states: "Since we do not succeed in fleeing it, let us, therefore, try to look the truth in the face. Let us try to assume our fundamental ambiguity. It is in the knowledge of the genuine conditions of our life that we must draw our strength to live and our reason for acting". Other continental philosophers suggest that concepts such as life, nature, and sex are ambiguous. Corey Anton has argued that we cannot be certain what is separate from or unified with something else: language, he asserts, divides what is not, in fact, separate. Following Ernest Becker, he argues that the desire to 'authoritatively disambiguate' the world and existence has led to numerous ideologies and historical events such as genocide. On this basis, he argues that ethics must focus on 'dialectically integrating opposites' and balancing tension, rather than seeking a priori validation or certainty. Like the existentialists and phenomenologists, he sees the ambiguity of life as the basis of creativity.

Literature and rhetoric

In literature and rhetoric, ambiguity can be a useful tool. Groucho Marx's classic joke depends on a grammatical ambiguity for its humor, for example: "Last night I shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas, I'll never know". An additional example of ambiguous humor comes from Shakespeare's Othello:

Cassio: Dost thou hear, my honest friend?

Clown: No, I hear not your honest friend. I hear you. (Othello, III, i)

Songs and poetry often rely on ambiguous words for artistic effect, as in the song title "Don't It Make My Brown Eyes Blue" (where "blue" can refer to the color, or to sadness).

In the narrative, ambiguity can be introduced in several ways: motive, plot, character. F. Scott Fitzgerald uses the latter type of ambiguity with notable effect in his novel The Great Gatsby.

Mathematical notation

Mathematical notation is a helpful tool that eliminates a lot of misunderstandings associated with natural language in physics and other sciences. Nonetheless, there are still some inherent ambiguities due to lexical, syntactic, and semantic reasons that persist in mathematical notation.

Names of functions

The ambiguity in the style of writing a function should not be confused with a multivalued function, which can (and should) be defined in a deterministic and unambiguous way. Several special functions still do not have established notations. Usually, the conversion to another notation requires to scale the argument or the resulting value; sometimes, the same name of the function is used, causing confusions. Examples of such underestablished functions:

- Sinc function

- Elliptic integral of the third kind; translating elliptic integral form MAPLE to Mathematica, one should replace the second argument to its square; dealing with complex values, this may cause problems.

- Exponential integral

- Hermite polynomial

Expressions

Ambiguous expressions often appear in physical and mathematical texts. It is common practice to omit multiplication signs in mathematical expressions. Also, it is common to give the same name to a variable and a function, for example, . Then, if one sees , there is no way to distinguish whether it means multiplied by , or function evaluated at argument equal to . In each case of use of such notations, the reader is supposed to be able to perform the deduction and reveal the true meaning.

Creators of algorithmic languages try to avoid ambiguities. Many algorithmic languages (C++ and Fortran) require the character * as symbol of multiplication. The Wolfram Language used in Mathematica allows the user to omit the multiplication symbol, but requires square brackets to indicate the argument of a function; square brackets are not allowed for grouping of expressions. Fortran, in addition, does not allow use of the same name (identifier) for different objects, for example, function and variable; in particular, the expression is qualified as an error.

The order of operations may depend on the context. In most programming languages, the operations of division and multiplication have equal priority and are executed from left to right. Until the last century, many editorials assumed that multiplication is performed first, for example, is interpreted as ; in this case, the insertion of parentheses is required when translating the formulas to an algorithmic language. In addition, it is common to write an argument of a function without parenthesis, which also may lead to ambiguity. In the scientific journal style, one uses roman letters to denote elementary functions, whereas variables are written using italics. For example, in mathematical journals the expression does not denote the sine function, but the product of the three variables , , , although in the informal notation of a slide presentation it may stand for .

Commas in multi-component subscripts and superscripts are sometimes omitted; this is also potentially ambiguous notation. For example, in the notation , the reader can only infer from the context whether it means a single-index object, taken with the subscript equal to product of variables , and , or it is an indication to a trivalent tensor.

Examples of potentially confusing ambiguous mathematical expressions

An expression such as can be understood to mean either or . Often the author's intention can be understood from the context, in cases where only one of the two makes sense, but an ambiguity like this should be avoided, for example by writing or .

The expression means in several texts, though it might be thought to mean , since commonly means . Conversely, might seem to mean , as this exponentiation notation usually denotes function iteration: in general, means . However, for trigonometric and hyperbolic functions, this notation conventionally means exponentiation of the result of function application.

The expression can be interpreted as meaning ; however, it is more commonly understood to mean .

Notations in quantum optics and quantum mechanics

It is common to define the coherent states in quantum optics with and states with fixed number of photons with . Then, there is an "unwritten rule": the state is coherent if there are more Greek characters than Latin characters in the argument, and -photon state if the Latin characters dominate. The ambiguity becomes even worse, if is used for the states with certain value of the coordinate, and means the state with certain value of the momentum, which may be used in books on quantum mechanics. Such ambiguities easily lead to confusions, especially if some normalized adimensional, dimensionless variables are used. Expression may mean a state with single photon, or the coherent state with mean amplitude equal to 1, or state with momentum equal to unity, and so on. The reader is supposed to guess from the context.

Ambiguous terms in physics and mathematics

Some physical quantities do not yet have established notations; their value (and sometimes even dimension, as in the case of the Einstein coefficients), depends on the system of notations. Many terms are ambiguous. Each use of an ambiguous term should be preceded by the definition, suitable for a specific case. Just like Ludwig Wittgenstein states in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: "... Only in the context of a proposition has a name meaning."

A highly confusing term is gain. For example, the sentence "the gain of a system should be doubled", without context, means close to nothing.

- It may mean that the ratio of the output voltage of an electric circuit to the input voltage should be doubled.

- It may mean that the ratio of the output power of an electric or optical circuit to the input power should be doubled.

- It may mean that the gain of the laser medium should be doubled, for example, doubling the population of the upper laser level in a quasi-two level system (assuming negligible absorption of the ground-state).

The term intensity is ambiguous when applied to light. The term can refer to any of irradiance, luminous intensity, radiant intensity, or radiance, depending on the background of the person using the term.

Also, confusions may be related with the use of atomic percent as measure of concentration of a dopant, or resolution of an imaging system, as measure of the size of the smallest detail that still can be resolved at the background of statistical noise. See also Accuracy and precision.

The Berry paradox arises as a result of systematic ambiguity in the meaning of terms such as "definable" or "nameable". Terms of this kind give rise to vicious circle fallacies. Other terms with this type of ambiguity are: satisfiable, true, false, function, property, class, relation, cardinal, and ordinal.

Mathematical interpretation of ambiguity

In mathematics and logic, ambiguity can be considered to be an instance of the logical concept of underdetermination—for example, leaves open what the value of is—while overdetermination, except when like , is a self-contradiction, also called inconsistency, paradoxicalness, or oxymoron, or in mathematics an inconsistent system—such as , which has no solution.

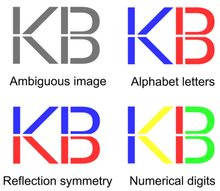

Logical ambiguity and self-contradiction is analogous to visual ambiguity and impossible objects, such as the Necker cube and impossible cube, or many of the drawings of M. C. Escher.

Constructed language

Some languages have been created with the intention of avoiding ambiguity, especially lexical ambiguity. Lojban and Loglan are two related languages that have been created for this, focusing chiefly on syntactic ambiguity as well. The languages can be both spoken and written. These languages are intended to provide a greater technical precision over big natural languages, although historically, such attempts at language improvement have been criticized. Languages composed from many diverse sources contain much ambiguity and inconsistency. The many exceptions to syntax and semantic rules are time-consuming and difficult to learn.

Biology

In structural biology, ambiguity has been recognized as a problem for studying protein conformations. The analysis of a protein three-dimensional structure consists in dividing the macromolecule into subunits called domains. The difficulty of this task arises from the fact that different definitions of what a domain is can be used (e.g. folding autonomy, function, thermodynamic stability, or domain motions), which sometimes results in a single protein having different—yet equally valid—domain assignments.

Christianity and Judaism

Christianity and Judaism employ the concept of paradox synonymously with "ambiguity". Many Christians and Jews endorse Rudolf Otto's description of the sacred as 'mysterium tremendum et fascinans', the awe-inspiring mystery that fascinates humans. The apocryphal Book of Judith is noted for the "ingenious ambiguity" expressed by its heroine; for example, she says to the villain of the story, Holofernes, "my lord will not fail to achieve his purposes", without specifying whether my lord refers to the villain or to God.

The orthodox Catholic writer G. K. Chesterton regularly employed paradox to tease out the meanings in common concepts that he found ambiguous or to reveal meaning often overlooked or forgotten in common phrases: the title of one of his most famous books, Orthodoxy (1908), itself employed such a paradox.

Music

In music, pieces or sections that confound expectations and may be or are interpreted simultaneously in different ways are ambiguous, such as some polytonality, polymeter, other ambiguous meters or rhythms, and ambiguous phrasing, or (Stein 2005, p. 79) any aspect of music. The music of Africa is often purposely ambiguous. To quote Sir Donald Francis Tovey (1935, p. 195), "Theorists are apt to vex themselves with vain efforts to remove uncertainty just where it has a high aesthetic value."

Visual art

In visual art, certain images are visually ambiguous, such as the Necker cube, which can be interpreted in two ways. Perceptions of such objects remain stable for a time, then may flip, a phenomenon called multistable perception. The opposite of such ambiguous images are impossible objects.

Pictures or photographs may also be ambiguous at the semantic level: the visual image is unambiguous, but the meaning and narrative may be ambiguous: is a certain facial expression one of excitement or fear, for instance?

Social psychology and the bystander effect

In social psychology, ambiguity is a factor used in determining peoples' responses to various situations. High levels of ambiguity in an emergency (e.g. an unconscious man lying on a park bench) make witnesses less likely to offer any sort of assistance, due to the fear that they may have misinterpreted the situation and acted unnecessarily. Alternately, non-ambiguous emergencies (e.g. an injured person verbally asking for help) elicit more consistent intervention and assistance. With regard to the bystander effect, studies have shown that emergencies deemed ambiguous trigger the appearance of the classic bystander effect (wherein more witnesses decrease the likelihood of any of them helping) far more than non-ambiguous emergencies.

Computer science

In computer science, the SI prefixes kilo-, mega- and giga- were historically used in certain contexts to mean either the first three powers of 1024 (1024, 1024 and 1024) contrary to the metric system in which these units unambiguously mean one thousand, one million, and one billion. This usage is particularly prevalent with electronic memory devices (e.g. DRAM) addressed directly by a binary machine register where a decimal interpretation makes no practical sense.

Subsequently, the Ki, Mi, and Gi prefixes were introduced so that binary prefixes could be written explicitly, also rendering k, M, and G unambiguous in texts conforming to the new standard—this led to a new ambiguity in engineering documents lacking outward trace of the binary prefixes (necessarily indicating the new style) as to whether the usage of k, M, and G remains ambiguous (old style) or not (new style). 1 M (where M is ambiguously 1000000 or 1048576) is less uncertain than the engineering value 1.0×10 (defined to designate the interval 950000 to 1050000). As non-volatile storage devices begin to exceed 1 GB in capacity (where the ambiguity begins to routinely impact the second significant digit), GB and TB almost always mean 10 and 10 bytes.

See also

- Misplaced Pages:Ambiguous words

- Abbreviation

- Ambiguity (law)

- Ambiguity tolerance–intolerance

- Amphibology

- Buzzword

- Decision problem

- Discrete mathematics

- Double entendre

- Equivocation

- Essentially contested concept

- Fallacy

- Formal fallacy

- Golden hammer

- Informal fallacy

- Pleonasm

- Self reference

- Semantics

- Uncertainty

- Volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity

- Word-sense disambiguation

References

- "And do you see its long nose and chin? At least, they look exactly like a nose and chin, that is don't they? But they really are two of its legs. You know a Caterpillar has got quantities of legs: you can see more of them, further down." Carroll, Lewis. The Nursery "Alice". Dover Publications (1966), p 27.

- Piantadosi, Steven; Tily, Hal; Gibson, Edward (2012). "The communicative function of ambiguity in language". Cognition. 122 (3): 280–291. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2011.10.004. hdl:1721.1/102465. PMID 22192697. S2CID 13726095.

- Finn, Emily (19 January 2012). "The advantage of ambiguity". MIT Press.

- Steven L. Small; Garrison W Cottrell; Michael K Tanenhaus (22 October 2013). Lexical Ambiguity Resolution: Perspective from Psycholinguistics, Neuropsychology and Artificial Intelligence. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-08-051013-2.

- ^ Critical Thinking, 10th ed., Ch 3, Moore, Brooke N. and Parker, Richard. McGraw-Hill, 2012

- ^ Abramovits, M.; Stegun, I. Handbook on mathematical functions. p. 228.

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1999). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Dover Publications Inc. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-486-40445-5.

- Russell/Whitehead, Principia Mathematica

- Goldstein, Laurence (1996). "Reflexivity, Contradiction, Paradox and M. C. Escher". Leonardo. 29 (4): 299–308. doi:10.2307/1576313. JSTOR 1576313. S2CID 191403643.

- ^ Postic, Guillaume; Ghouzam, Yassine; Chebrek, Romain; Gelly, Jean-Christophe (2017). "An ambiguity principle for assigning protein structural domains". Science Advances. 3 (1): e1600552. Bibcode:2017SciA....3E0552P. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1600552. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 5235333. PMID 28097215.

- Jerusalem Bible (1966), footnote a at Judith 11:5

- Judith 11:6

- deSilva, David A. (20 February 2018). Introducing the Apocrypha: Message, Context, and Significance. Baker Books. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-4934-1307-2.

- Chesterton, G. K., Orthodoxy, especially p. 32

- Seckel, Al (2009). Optical Illusions: The Science of Visual Perception. Canada: Firefly Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1554071722.

- Mason, David; Allen, Bem P. (1976). "The Bystander Effect as a Function of Ambiguity and Emergency Character". The Journal of Social Psychology. 100: 145–146. doi:10.1080/00224545.1976.9711917.

External links

- [REDACTED] Media related to Ambiguity at Wikimedia Commons

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Ambiguity". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Ambiguity at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- Ambiguity at PhilPapers

- Collection of Ambiguous or Inconsistent/Incomplete Statements

- Leaving out ambiguities when writing

| Common fallacies (list) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Informal |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Philosophical logic | |

|---|---|

| Critical thinking and informal logic | |

| Theories of deduction | |

. Then, if one sees

. Then, if one sees  , there is no way to distinguish whether it means

, there is no way to distinguish whether it means  , or function

, or function  evaluated at argument equal to

evaluated at argument equal to  is interpreted as

is interpreted as  ; in this case, the insertion of parentheses is required when translating the formulas to an algorithmic language. In addition, it is common to write an argument of a function without parenthesis, which also may lead to ambiguity.

In the

; in this case, the insertion of parentheses is required when translating the formulas to an algorithmic language. In addition, it is common to write an argument of a function without parenthesis, which also may lead to ambiguity.

In the  does not denote the

does not denote the  ,

,  ,

,  , although in the informal notation of a slide presentation it may stand for

, although in the informal notation of a slide presentation it may stand for  .

.

, the reader can only infer from the context whether it means a single-index object, taken with the subscript equal to product of variables

, the reader can only infer from the context whether it means a single-index object, taken with the subscript equal to product of variables  ,

,  , or it is an indication to a trivalent

, or it is an indication to a trivalent  can be understood to mean either

can be understood to mean either  or

or  . Often the author's intention can be understood from the context, in cases where only one of the two makes sense, but an ambiguity like this should be avoided, for example by writing

. Often the author's intention can be understood from the context, in cases where only one of the two makes sense, but an ambiguity like this should be avoided, for example by writing  or

or  .

.

means

means  in several texts, though it might be thought to mean

in several texts, though it might be thought to mean  , since

, since  commonly means

commonly means  . Conversely,

. Conversely,  might seem to mean

might seem to mean  , as this

, as this  means

means  . However, for

. However, for  can be interpreted as meaning

can be interpreted as meaning  ; however, it is more commonly understood to mean

; however, it is more commonly understood to mean  .

.

and states with fixed number of photons with

and states with fixed number of photons with  . Then, there is an "unwritten rule": the state is coherent if there are more Greek characters than Latin characters in the argument, and

. Then, there is an "unwritten rule": the state is coherent if there are more Greek characters than Latin characters in the argument, and  is used for the states with certain value of the coordinate, and

is used for the states with certain value of the coordinate, and  means the state with certain value of the momentum, which may be used in books on

means the state with certain value of the momentum, which may be used in books on  may mean a state with single photon, or the coherent state with mean amplitude equal to 1, or state with momentum equal to unity, and so on. The reader is supposed to guess from the context.

may mean a state with single photon, or the coherent state with mean amplitude equal to 1, or state with momentum equal to unity, and so on. The reader is supposed to guess from the context.

leaves open what the value of

leaves open what the value of  is—while overdetermination, except when like

is—while overdetermination, except when like  , is a

, is a  , which has no solution.

, which has no solution.