| Thermodynamics | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The classical Carnot heat engine The classical Carnot heat engine | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Branches | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Laws | |||||||||||||||||||||

Systems

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

System propertiesNote: Conjugate variables in italics

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Material properties

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Equations | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potentials | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientists | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Specific heat capacity | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Specific heat |

| Common symbols | c |

| SI unit | J⋅kg⋅K |

| In SI base units | m⋅K⋅s |

| Intensive? | Yes |

| Dimension | L⋅T⋅K |

In thermodynamics, the specific heat capacity (symbol c) of a substance is the amount of heat that must be added to one unit of mass of the substance in order to cause an increase of one unit in temperature. It is also referred to as Massic heat capacity or as the Specific heat. More formally it is the heat capacity of a sample of the substance divided by the mass of the sample. The SI unit of specific heat capacity is joule per kelvin per kilogram, J⋅kg⋅K. For example, the heat required to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water by 1 K is 4184 joules, so the specific heat capacity of water is 4184 J⋅kg⋅K.

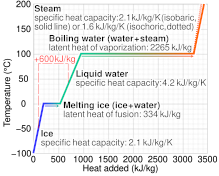

Specific heat capacity often varies with temperature, and is different for each state of matter. Liquid water has one of the highest specific heat capacities among common substances, about 4184 J⋅kg⋅K at 20 °C; but that of ice, just below 0 °C, is only 2093 J⋅kg⋅K. The specific heat capacities of iron, granite, and hydrogen gas are about 449 J⋅kg⋅K, 790 J⋅kg⋅K, and 14300 J⋅kg⋅K, respectively. While the substance is undergoing a phase transition, such as melting or boiling, its specific heat capacity is technically undefined, because the heat goes into changing its state rather than raising its temperature.

The specific heat capacity of a substance, especially a gas, may be significantly higher when it is allowed to expand as it is heated (specific heat capacity at constant pressure) than when it is heated in a closed vessel that prevents expansion (specific heat capacity at constant volume). These two values are usually denoted by and , respectively; their quotient is the heat capacity ratio.

The term specific heat may also refer to the ratio between the specific heat capacities of a substance at a given temperature and of a reference substance at a reference temperature, such as water at 15 °C; much in the fashion of specific gravity. Specific heat capacity is also related to other intensive measures of heat capacity with other denominators. If the amount of substance is measured as a number of moles, one gets the molar heat capacity instead, whose SI unit is joule per kelvin per mole, J⋅mol⋅K. If the amount is taken to be the volume of the sample (as is sometimes done in engineering), one gets the volumetric heat capacity, whose SI unit is joule per kelvin per cubic meter, J⋅m⋅K.

History

Discovery of specific heat

One of the first scientists to use the concept was Joseph Black, an 18th-century medical doctor and professor of medicine at Glasgow University. He measured the specific heat capacities of many substances, using the term capacity for heat. In 1756 or soon thereafter, Black began an extensive study of heat. In 1760 he realized that when two different substances of equal mass but different temperatures are mixed, the changes in number of degrees in the two substances differ, though the heat gained by the cooler substance and lost by the hotter is the same. Black related an experiment conducted by Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit on behalf of Dutch physician Herman Boerhaave. For clarity, he then described a hypothetical, but realistic variant of the experiment: If equal masses of 100 °F water and 150 °F mercury are mixed, the water temperature increases by 20 ° and the mercury temperature decreases by 30 ° (both arriving at 120 °F), even though the heat gained by the water and lost by the mercury is the same. This clarified the distinction between heat and temperature. It also introduced the concept of specific heat capacity, being different for different substances. Black wrote: “Quicksilver ... has less capacity for the matter of heat than water.”

Definition

The specific heat capacity of a substance, usually denoted by or , is the heat capacity of a sample of the substance, divided by the mass of the sample: where represents the amount of heat needed to uniformly raise the temperature of the sample by a small increment .

Like the heat capacity of an object, the specific heat capacity of a substance may vary, sometimes substantially, depending on the starting temperature of the sample and the pressure applied to it. Therefore, it should be considered a function of those two variables.

These parameters are usually specified when giving the specific heat capacity of a substance. For example, "Water (liquid): = 4187 J⋅kg⋅K (15 °C)." When not specified, published values of the specific heat capacity generally are valid for some standard conditions for temperature and pressure.

However, the dependency of on starting temperature and pressure can often be ignored in practical contexts, e.g. when working in narrow ranges of those variables. In those contexts one usually omits the qualifier and approximates the specific heat capacity by a constant suitable for those ranges.

Specific heat capacity is an intensive property of a substance, an intrinsic characteristic that does not depend on the size or shape of the amount in consideration. (The qualifier "specific" in front of an extensive property often indicates an intensive property derived from it.)

Variations

The injection of heat energy into a substance, besides raising its temperature, usually causes an increase in its volume and/or its pressure, depending on how the sample is confined. The choice made about the latter affects the measured specific heat capacity, even for the same starting pressure and starting temperature . Two particular choices are widely used:

- If the pressure is kept constant (for instance, at the ambient atmospheric pressure), and the sample is allowed to expand, the expansion generates work, as the force from the pressure displaces the enclosure or the surrounding fluid. That work must come from the heat energy provided. The specific heat capacity thus obtained is said to be measured at constant pressure (or isobaric) and is often denoted .

- On the other hand, if the expansion is prevented – for example, by a sufficiently rigid enclosure or by increasing the external pressure to counteract the internal one – no work is generated, and the heat energy that would have gone into it must instead contribute to the internal energy of the sample, including raising its temperature by an extra amount. The specific heat capacity obtained this way is said to be measured at constant volume (or isochoric) and denoted .

The value of is always less than the value of for all fluids. This difference is particularly notable in gases where values under constant pressure are typically 30% to 66.7% greater than those at constant volume. Hence the heat capacity ratio of gases is typically between 1.3 and 1.67.

Applicability

The specific heat capacity can be defined and measured for gases, liquids, and solids of fairly general composition and molecular structure. These include gas mixtures, solutions and alloys, or heterogenous materials such as milk, sand, granite, and concrete, if considered at a sufficiently large scale.

The specific heat capacity can be defined also for materials that change state or composition as the temperature and pressure change, as long as the changes are reversible and gradual. Thus, for example, the concepts are definable for a gas or liquid that dissociates as the temperature increases, as long as the products of the dissociation promptly and completely recombine when it drops.

The specific heat capacity is not meaningful if the substance undergoes irreversible chemical changes, or if there is a phase change, such as melting or boiling, at a sharp temperature within the range of temperatures spanned by the measurement.

Measurement

The specific heat capacity of a substance is typically determined according to the definition; namely, by measuring the heat capacity of a sample of the substance, usually with a calorimeter, and dividing by the sample's mass. Several techniques can be applied for estimating the heat capacity of a substance, such as differential scanning calorimetry.

The specific heat capacities of gases can be measured at constant volume, by enclosing the sample in a rigid container. On the other hand, measuring the specific heat capacity at constant volume can be prohibitively difficult for liquids and solids, since one often would need impractical pressures in order to prevent the expansion that would be caused by even small increases in temperature. Instead, the common practice is to measure the specific heat capacity at constant pressure (allowing the material to expand or contract as it wishes), determine separately the coefficient of thermal expansion and the compressibility of the material, and compute the specific heat capacity at constant volume from these data according to the laws of thermodynamics.

Units

International system

The SI unit for specific heat capacity is joule per kelvin per kilogram J/kg⋅K, J⋅K⋅kg. Since an increment of temperature of one degree Celsius is the same as an increment of one kelvin, that is the same as joule per degree Celsius per kilogram: J/(kg⋅°C). Sometimes the gram is used instead of kilogram for the unit of mass: 1 J⋅g⋅K = 1000 J⋅kg⋅K.

The specific heat capacity of a substance (per unit of mass) has dimension L⋅Θ⋅T, or (L/T)/Θ. Therefore, the SI unit J⋅kg⋅K is equivalent to metre squared per second squared per kelvin (m⋅K⋅s).

Imperial engineering units

Professionals in construction, civil engineering, chemical engineering, and other technical disciplines, especially in the United States, may use English Engineering units including the pound (lb = 0.45359237 kg) as the unit of mass, the degree Fahrenheit or Rankine (°R = 5/9 K, about 0.555556 K) as the unit of temperature increment, and the British thermal unit (BTU ≈ 1055.056 J), as the unit of heat.

In those contexts, the unit of specific heat capacity is BTU/lb⋅°R, or 1 BTU/lb⋅°R = 4186.68J/kg⋅K. The BTU was originally defined so that the average specific heat capacity of water would be 1 BTU/lb⋅°F. Note the value's similarity to that of the calorie - 4187 J/kg⋅°C ≈ 4184 J/kg⋅°C (~.07%) - as they are essentially measuring the same energy, using water as a basis reference, scaled to their systems' respective lbs and °F, or kg and °C.

Calories

In chemistry, heat amounts were often measured in calories. Confusingly, there are two common units with that name, respectively denoted cal and Cal:

- the small calorie (gram-calorie, cal) is 4.184 J exactly. It was originally defined so that the specific heat capacity of liquid water would be 1 cal/(°C⋅g).

- The grand calorie (kilocalorie, kilogram-calorie, food calorie, kcal, Cal) is 1000 small calories, 4184 J exactly. It was defined so that the specific heat capacity of water would be 1 Cal/(°C⋅kg).

While these units are still used in some contexts (such as kilogram calorie in nutrition), their use is now deprecated in technical and scientific fields. When heat is measured in these units, the unit of specific heat capacity is usually:

1 cal/°C⋅g = 1 Cal/°C⋅kg = 1 kcal/°C⋅kg = 4184 J/kg⋅K = 4.184 kJ/kg⋅K.Note that while cal is 1⁄1000 of a Cal or kcal, it is also per gram instead of kilogram: ergo, in either unit, the specific heat capacity of water is approximately 1.

Physical basis

Main article: Molar heat capacity § Physical basisThe temperature of a sample of a substance reflects the average kinetic energy of its constituent particles (atoms or molecules) relative to its center of mass. However, not all energy provided to a sample of a substance will go into raising its temperature, exemplified via the equipartition theorem.

Monatomic gases

Statistical mechanics predicts that at room temperature and ordinary pressures, an isolated atom in a gas cannot store any significant amount of energy except in the form of kinetic energy, unless multiple electronic states are accessible at room temperature (such is the case for atomic fluorine). Thus, the heat capacity per mole at room temperature is the same for all of the noble gases as well as for many other atomic vapors. More precisely, and , where is the ideal gas unit (which is the product of Boltzmann conversion constant from kelvin microscopic energy unit to the macroscopic energy unit joule, and the Avogadro number).

Therefore, the specific heat capacity (per gram, not per mole) of a monatomic gas will be inversely proportional to its (adimensional) atomic weight . That is, approximately,

For the noble gases, from helium to xenon, these computed values are

| Gas | He | Ne | Ar | Kr | Xe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.00 | 20.17 | 39.95 | 83.80 | 131.29 | |

| (J⋅K⋅kg) | 3118 | 618.3 | 312.2 | 148.8 | 94.99 |

| (J⋅K⋅kg) | 5197 | 1031 | 520.3 | 248.0 | 158.3 |

Polyatomic gases

On the other hand, a polyatomic gas molecule (consisting of two or more atoms bound together) can store heat energy in additional degrees of freedom. Its kinetic energy contributes to the heat capacity in the same way as monatomic gases, but there are also contributions from the rotations of the molecule and vibration of the atoms relative to each other (including internal potential energy).

There may also be contributions to the heat capacity from excited electronic states for molecules where the energy gap between the ground state and the excited state is sufficiently small, such as NO. For a few systems, quantum spin statistics can also be important contributions to the heat capacity, even at room temperature. The analysis of the heat capacity of H

2 due to ortho/para separation, which arises from nuclear spin statistics, has been referred to as "one of the great triumphs of post-quantum mechanical statistical mechanics."

These extra degrees of freedom or "modes" contribute to the specific heat capacity of the substance. Namely, when heat energy is injected into a gas with polyatomic molecules, only part of it will go into increasing their kinetic energy, and hence the temperature; the rest will go to into the other degrees of freedom. To achieve the same increase in temperature, more heat energy is needed for a gram of that substance than for a gram of a monatomic gas. Thus, the specific heat capacity per mole of a polyatomic gas depends both on the molecular mass and the number of degrees of freedom of the molecules.

Quantum statistical mechanics predicts that each rotational or vibrational mode can only take or lose energy in certain discrete amounts (quanta), and that this affects the system’s thermodynamic properties. Depending on the temperature, the average heat energy per molecule may be too small compared to the quanta needed to activate some of those degrees of freedom. Those modes are said to be "frozen out". In that case, the specific heat capacity of the substance increases with temperature, sometimes in a step-like fashion as mode becomes unfrozen and starts absorbing part of the input heat energy.

For example, the molar heat capacity of nitrogen N

2 at constant volume is (at 15 °C, 1 atm), which is . That is the value expected from the Equipartition Theorem if each molecule had 5 kinetic degrees of freedom. These turn out to be three degrees of the molecule's velocity vector, plus two degrees from its rotation about an axis through the center of mass and perpendicular to the line of the two atoms. Because of those two extra degrees of freedom, the specific heat capacity of N

2 (736 J⋅K⋅kg) is greater than that of an hypothetical monatomic gas with the same molecular mass 28 (445 J⋅K⋅kg), by a factor of 5/3. The vibrational and electronic degrees of freedom do not contribute significantly to the heat capacity in this case, due to the relatively large energy level gaps for both vibrational and electronic excitation in this molecule.

This value for the specific heat capacity of nitrogen is practically constant from below −150 °C to about 300 °C. In that temperature range, the two additional degrees of freedom that correspond to vibrations of the atoms, stretching and compressing the bond, are still "frozen out". At about that temperature, those modes begin to "un-freeze" as vibrationally excited states become accessible. As a result starts to increase rapidly at first, then slower as it tends to another constant value. It is 35.5 J⋅K⋅mol at 1500 °C, 36.9 at 2500 °C, and 37.5 at 3500 °C. The last value corresponds almost exactly to the value predicted by the Equipartition Theorem, since in the high-temperature limit the theorem predicts that the vibrational degree of freedom contributes twice as much to the heat capacity as any one of the translational or rotational degrees of freedom.

Derivations of heat capacity

Relation between specific heat capacities

Starting from the fundamental thermodynamic relation one can show,

where

- is the coefficient of thermal expansion,

- is the isothermal compressibility, and

- is density.

A derivation is discussed in the article Relations between specific heats.

For an ideal gas, if is expressed as molar density in the above equation, this equation reduces simply to Mayer's relation,

where and are intensive property heat capacities expressed on a per mole basis at constant pressure and constant volume, respectively.

Specific heat capacity

The specific heat capacity of a material on a per mass basis is

which in the absence of phase transitions is equivalent to

where

- is the heat capacity of a body made of the material in question,

- is the mass of the body,

- is the volume of the body, and

- is the density of the material.

For gases, and also for other materials under high pressures, there is need to distinguish between different boundary conditions for the processes under consideration (since values differ significantly between different conditions). Typical processes for which a heat capacity may be defined include isobaric (constant pressure, ) or isochoric (constant volume, ) processes. The corresponding specific heat capacities are expressed as

A related parameter to is , the volumetric heat capacity. In engineering practice, for solids or liquids often signifies a volumetric heat capacity, rather than a constant-volume one. In such cases, the mass-specific heat capacity is often explicitly written with the subscript , as . Of course, from the above relationships, for solids one writes

For pure homogeneous chemical compounds with established molecular or molar mass or a molar quantity is established, heat capacity as an intensive property can be expressed on a per mole basis instead of a per mass basis by the following equations analogous to the per mass equations:

where n = number of moles in the body or thermodynamic system. One may refer to such a per mole quantity as molar heat capacity to distinguish it from specific heat capacity on a per-mass basis.

Polytropic heat capacity

The polytropic heat capacity is calculated at processes if all the thermodynamic properties (pressure, volume, temperature) change

The most important polytropic processes run between the adiabatic and the isotherm functions, the polytropic index is between 1 and the adiabatic exponent (γ or κ)

Dimensionless heat capacity

The dimensionless heat capacity of a material is

where

- C is the heat capacity of a body made of the material in question (J/K)

- n is the amount of substance in the body (mol)

- R is the gas constant (J⋅K⋅mol)

- N is the number of molecules in the body. (dimensionless)

- kB is the Boltzmann constant (J⋅K)

Again, SI units shown for example.

Read more about the quantities of dimension one at BIPM

In the Ideal gas article, dimensionless heat capacity is expressed as .

Heat capacity at absolute zero

From the definition of entropy

the absolute entropy can be calculated by integrating from zero kelvins temperature to the final temperature Tf

The heat capacity must be zero at zero temperature in order for the above integral not to yield an infinite absolute entropy, thus violating the third law of thermodynamics. One of the strengths of the Debye model is that (unlike the preceding Einstein model) it predicts the proper mathematical form of the approach of heat capacity toward zero, as absolute zero temperature is approached.

Solid phase

The theoretical maximum heat capacity for larger and larger multi-atomic gases at higher temperatures, also approaches the Dulong–Petit limit of 3R, so long as this is calculated per mole of atoms, not molecules. The reason is that gases with very large molecules, in theory have almost the same high-temperature heat capacity as solids, lacking only the (small) heat capacity contribution that comes from potential energy that cannot be stored between separate molecules in a gas.

The Dulong–Petit limit results from the equipartition theorem, and as such is only valid in the classical limit of a microstate continuum, which is a high temperature limit. For light and non-metallic elements, as well as most of the common molecular solids based on carbon compounds at standard ambient temperature, quantum effects may also play an important role, as they do in multi-atomic gases. These effects usually combine to give heat capacities lower than 3R per mole of atoms in the solid, although in molecular solids, heat capacities calculated per mole of molecules in molecular solids may be more than 3R. For example, the heat capacity of water ice at the melting point is about 4.6R per mole of molecules, but only 1.5R per mole of atoms. The lower than 3R number "per atom" (as is the case with diamond and beryllium) results from the “freezing out” of possible vibration modes for light atoms at suitably low temperatures, just as in many low-mass-atom gases at room temperatures. Because of high crystal binding energies, these effects are seen in solids more often than liquids: for example the heat capacity of liquid water is twice that of ice at near the same temperature, and is again close to the 3R per mole of atoms of the Dulong–Petit theoretical maximum.

For a more modern and precise analysis of the heat capacities of solids, especially at low temperatures, it is useful to use the idea of phonons. See Debye model.

Theoretical estimation

The path integral Monte Carlo method is a numerical approach for determining the values of heat capacity, based on quantum dynamical principles. However, good approximations can be made for gases in many states using simpler methods outlined below. For many solids composed of relatively heavy atoms (atomic number > iron), at non-cryogenic temperatures, the heat capacity at room temperature approaches 3R = 24.94 joules per kelvin per mole of atoms (Dulong–Petit law, R is the gas constant). Low temperature approximations for both gases and solids at temperatures less than their characteristic Einstein temperatures or Debye temperatures can be made by the methods of Einstein and Debye discussed below.

- Water (liquid): CP = 4185.5 J⋅K⋅kg (15 °C, 101.325 kPa)

- Water (liquid): CVH = 74.539 J⋅K⋅mol (25 °C)

For liquids and gases, it is important to know the pressure to which given heat capacity data refer. Most published data are given for standard pressure. However, different standard conditions for temperature and pressure have been defined by different organizations. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) changed its recommendation from one atmosphere to the round value 100 kPa (≈750.062 Torr).

Relation between heat capacities

Main article: Relations between heat capacitiesMeasuring the specific heat capacity at constant volume can be prohibitively difficult for liquids and solids. That is, small temperature changes typically require large pressures to maintain a liquid or solid at constant volume, implying that the containing vessel must be nearly rigid or at least very strong (see coefficient of thermal expansion and compressibility). Instead, it is easier to measure the heat capacity at constant pressure (allowing the material to expand or contract freely) and solve for the heat capacity at constant volume using mathematical relationships derived from the basic thermodynamic laws.

The heat capacity ratio, or adiabatic index, is the ratio of the heat capacity at constant pressure to heat capacity at constant volume. It is sometimes also known as the isentropic expansion factor.

Ideal gas

For an ideal gas, evaluating the partial derivatives above according to the equation of state, where R is the gas constant, for an ideal gas

Substituting

this equation reduces simply to Mayer's relation:

The differences in heat capacities as defined by the above Mayer relation is only exact for an ideal gas and would be different for any real gas.

Specific heat capacity

The specific heat capacity of a material on a per mass basis is

which in the absence of phase transitions is equivalent to

where

- is the heat capacity of a body made of the material in question,

- is the mass of the body,

- is the volume of the body,

- is the density of the material.

For gases, and also for other materials under high pressures, there is need to distinguish between different boundary conditions for the processes under consideration (since values differ significantly between different conditions). Typical processes for which a heat capacity may be defined include isobaric (constant pressure, ) or isochoric (constant volume, ) processes. The corresponding specific heat capacities are expressed as

From the results of the previous section, dividing through by the mass gives the relation

A related parameter to is , the volumetric heat capacity. In engineering practice, for solids or liquids often signifies a volumetric heat capacity, rather than a constant-volume one. In such cases, the specific heat capacity is often explicitly written with the subscript , as . Of course, from the above relationships, for solids one writes

For pure homogeneous chemical compounds with established molecular or molar mass, or a molar quantity, heat capacity as an intensive property can be expressed on a per-mole basis instead of a per-mass basis by the following equations analogous to the per mass equations:

where n is the number of moles in the body or thermodynamic system. One may refer to such a per-mole quantity as molar heat capacity to distinguish it from specific heat capacity on a per-mass basis.

Polytropic heat capacity

The polytropic heat capacity is calculated at processes if all the thermodynamic properties (pressure, volume, temperature) change:

The most important polytropic processes run between the adiabatic and the isotherm functions, the polytropic index is between 1 and the adiabatic exponent (γ or κ).

Dimensionless heat capacity

The dimensionless heat capacity of a material is

where

- is the heat capacity of a body made of the material in question (J/K),

- n is the amount of substance in the body (mol),

- R is the gas constant (J/(K⋅mol)),

- N is the number of molecules in the body (dimensionless),

- kB is the Boltzmann constant (J/(K⋅molecule)).

In the ideal gas article, dimensionless heat capacity is expressed as and is related there directly to half the number of degrees of freedom per particle. This holds true for quadratic degrees of freedom, a consequence of the equipartition theorem.

More generally, the dimensionless heat capacity relates the logarithmic increase in temperature to the increase in the dimensionless entropy per particle , measured in nats.

Alternatively, using base-2 logarithms, relates the base-2 logarithmic increase in temperature to the increase in the dimensionless entropy measured in bits.

Heat capacity at absolute zero

From the definition of entropy

the absolute entropy can be calculated by integrating from zero to the final temperature Tf:

Thermodynamic derivation

In theory, the specific heat capacity of a substance can also be derived from its abstract thermodynamic modeling by an equation of state and an internal energy function.

State of matter in a homogeneous sample

To apply the theory, one considers the sample of the substance (solid, liquid, or gas) for which the specific heat capacity can be defined; in particular, that it has homogeneous composition and fixed mass . Assume that the evolution of the system is always slow enough for the internal pressure and temperature be considered uniform throughout. The pressure would be equal to the pressure applied to it by the enclosure or some surrounding fluid, such as air.

The state of the material can then be specified by three parameters: its temperature , the pressure , and its specific volume , where is the volume of the sample. (This quantity is the reciprocal of the material's density .) Like and , the specific volume is an intensive property of the material and its state, that does not depend on the amount of substance in the sample.

Those variables are not independent. The allowed states are defined by an equation of state relating those three variables: The function depends on the material under consideration. The specific internal energy stored internally in the sample, per unit of mass, will then be another function of these state variables, that is also specific of the material. The total internal energy in the sample then will be .

For some simple materials, like an ideal gas, one can derive from basic theory the equation of state and even the specific internal energy In general, these functions must be determined experimentally for each substance.

Conservation of energy

The absolute value of this quantity is undefined, and (for the purposes of thermodynamics) the state of "zero internal energy" can be chosen arbitrarily. However, by the law of conservation of energy, any infinitesimal increase in the total internal energy must be matched by the net flow of heat energy into the sample, plus any net mechanical energy provided to it by enclosure or surrounding medium on it. The latter is , where is the change in the sample's volume in that infinitesimal step. Therefore

hence

If the volume of the sample (hence the specific volume of the material) is kept constant during the injection of the heat amount , then the term is zero (no mechanical work is done). Then, dividing by ,

where is the change in temperature that resulted from the heat input. The left-hand side is the specific heat capacity at constant volume of the material.

For the heat capacity at constant pressure, it is useful to define the specific enthalpy of the system as the sum . An infinitesimal change in the specific enthalpy will then be

therefore

If the pressure is kept constant, the second term on the left-hand side is zero, and

The left-hand side is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure of the material.

Connection to equation of state

In general, the infinitesimal quantities are constrained by the equation of state and the specific internal energy function. Namely,

Here denotes the (partial) derivative of the state equation with respect to its argument, keeping the other two arguments fixed, evaluated at the state in question. The other partial derivatives are defined in the same way. These two equations on the four infinitesimal increments normally constrain them to a two-dimensional linear subspace space of possible infinitesimal state changes, that depends on the material and on the state. The constant-volume and constant-pressure changes are only two particular directions in this space.

This analysis also holds no matter how the energy increment is injected into the sample, namely by heat conduction, irradiation, electromagnetic induction, radioactive decay, etc.

Relation between heat capacities

For any specific volume , denote the function that describes how the pressure varies with the temperature , as allowed by the equation of state, when the specific volume of the material is forcefully kept constant at . Analogously, for any pressure , let be the function that describes how the specific volume varies with the temperature, when the pressure is kept constant at . Namely, those functions are such that

and

for any values of . In other words, the graphs of and are slices of the surface defined by the state equation, cut by planes of constant and constant , respectively.

Then, from the fundamental thermodynamic relation it follows that

This equation can be rewritten as

where

- is the coefficient of thermal expansion,

- is the isothermal compressibility,

both depending on the state .

The heat capacity ratio, or adiabatic index, is the ratio of the heat capacity at constant pressure to heat capacity at constant volume. It is sometimes also known as the isentropic expansion factor.

Calculation from first principles

The path integral Monte Carlo method is a numerical approach for determining the values of heat capacity, based on quantum dynamical principles. However, good approximations can be made for gases in many states using simpler methods outlined below. For many solids composed of relatively heavy atoms (atomic number > iron), at non-cryogenic temperatures, the heat capacity at room temperature approaches 3R = 24.94 joules per kelvin per mole of atoms (Dulong–Petit law, R is the gas constant). Low temperature approximations for both gases and solids at temperatures less than their characteristic Einstein temperatures or Debye temperatures can be made by the methods of Einstein and Debye discussed below. However, attention should be made for the consistency of such ab-initio considerations when used along with an equation of state for the considered material.

Ideal gas

For an ideal gas, evaluating the partial derivatives above according to the equation of state, where R is the gas constant, for an ideal gas

Substituting

this equation reduces simply to Mayer's relation:

The differences in heat capacities as defined by the above Mayer relation is only exact for an ideal gas and would be different for any real gas.

See also

- Specific heat of melting (Enthalpy of fusion)

- Specific heat of vaporization (Enthalpy of vaporization)

- Frenkel line

- Heat capacity ratio

- Heat equation

- Heat transfer coefficient

- History of thermodynamics

- Joback method (Estimation of heat capacities)

- Latent heat

- Material properties (thermodynamics)

- Quantum statistical mechanics

- R-value (insulation)

- Enthalpy of vaporization

- Enthalpy of fusion

- Statistical mechanics

- Table of specific heat capacities

- Thermal mass

- Thermodynamic databases for pure substances

- Thermodynamic equations

- Volumetric heat capacity

Notes

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Standard Pressure". doi:10.1351/goldbook.S05921.

References

- Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert; Walker, Jearl (2001). Fundamentals of Physics (6th ed.). New York, NY US: John Wiley & Sons.

- Open University (2008). S104 Book 3 Energy and Light, p. 59. The Open University. ISBN 9781848731646.

- Open University (2008). S104 Book 3 Energy and Light, p. 179. The Open University. ISBN 9781848731646.

- Engineering ToolBox (2003). "Specific Heat of some common Substances".

- (2001): Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed.; as quoted by Encyclopedia.com. Columbia University Press. Accessed on 2019-04-11.

- Laidler, Keith J. (1993). The World of Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855919-4.

- Ramsay, William (1918). The life and letters of Joseph Black, M.D. Constable. pp. 38–39.

- Black, Joseph (1807). Robison, John (ed.). Lectures on the Elements of Chemistry: Delivered in the University of Edinburgh. Vol. 1. Mathew Carey. pp. 76–77.

- West, John B. (2014-06-15). "Joseph Black, carbon dioxide, latent heat, and the beginnings of the discovery of the respiratory gases". American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 306 (12): L1057 – L1063. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00020.2014. ISSN 1040-0605.

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-04, retrieved 2021-12-16

- "Water – Thermal Properties". Engineeringtoolbox.com. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Physical Chemistry Division. "Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry" (PDF). Blackwell Sciences. p. 7.

The adjective specific before the name of an extensive quantity is often used to mean divided by mass.

- Lange's Handbook of Chemistry, 10th ed., page 1524.

- Quick, C. R.; Schawe, J. E. K.; Uggowitzer, P. J.; Pogatscher, S. (2019-07-01). "Measurement of specific heat capacity via fast scanning calorimetry—Accuracy and loss corrections". Thermochimica Acta. Special Issue on occasion of the 65th birthday of Christoph Schick. 677: 12–20. Bibcode:2019TcAc..677...12Q. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2019.03.021. ISSN 0040-6031.

- Pogatscher, S.; Leutenegger, D.; Schawe, J. E. K.; Uggowitzer, P. J.; Löffler, J. F. (September 2016). "Solid–solid phase transitions via melting in metals". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 11113. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711113P. doi:10.1038/ncomms11113. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4844691. PMID 27103085.

- Koch, Werner (2013). VDI Steam Tables (4 ed.). Springer. p. 8. ISBN 9783642529412. Published under the auspices of the Verein Deutscher Ingenieure (VDI).

- Cardarelli, Francois (2012). Scientific Unit Conversion: A Practical Guide to Metrication. M.J. Shields (translation) (2 ed.). Springer. p. 19. ISBN 9781447108054.

- From direct values: 1BTU/lb⋅°R × 1055.06J/BTU × (1/0.45359237)lb/kg x 9/5°R/K = 4186.82J/kg⋅K

- °F=°R

- °C=K

- McQuarrie, Donald A. (1973). Statistical Thermodynamics. New York, NY: University Science Books. pp. 83–85.

- "6.6: Electronic Partition Function". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2020-11-26. Retrieved 2024-12-16.

- Bonhoeffer, K.F.; Harteck, P. (1926). "Über Para- und Orthowasserstoff". Z. Phys. Chem. 4B: 113.

- McQuarrie, Donald A. (1973). Statistical Thermodynamics. New York, NY: University Science Books. p. 107.

- Feynman, R., The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. 1, ch. 40, pp. 7–8

- Reif, F. (1965). Fundamentals of statistical and thermal physics. McGraw-Hill. pp. 253–254.

- Kittel, Charles; Kroemer, Herbert (2000). Thermal physics. W. H. Freeman. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-7167-1088-2.

- Thornton, Steven T. and Rex, Andrew (1993) Modern Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Saunders College Publishing

- Chase, M.W. Jr. (1998) NIST-JANAF Themochemical Tables, Fourth Edition, In Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, Monograph 9, pages 1–1951.

- "About the unit one".

- Yunus A. Cengel and Michael A. Boles, Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 7th Edition, McGraw-Hill, 2010, ISBN 007-352932-X.

- Fraundorf, P. (2003). "Heat capacity in bits". American Journal of Physics. 71 (11): 1142. arXiv:cond-mat/9711074. Bibcode:2003AmJPh..71.1142F. doi:10.1119/1.1593658. S2CID 18742525.

- Feynman, Richard, The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. 1, Ch. 45

- S. Benjelloun, "Thermodynamic identities and thermodynamic consistency of Equation of States", Link to Archiv e-print Link to Hal e-print

- Cengel, Yunus A. and Boles, Michael A. (2010) Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 7th Edition, McGraw-Hill ISBN 007-352932-X.

Further reading

- Emmerich Wilhelm & Trevor M. Letcher, Eds., 2010, Heat Capacities: Liquids, Solutions and Vapours, Cambridge, U.K.:Royal Society of Chemistry, ISBN 0-85404-176-1. A very recent outline of selected traditional aspects of the title subject, including a recent specialist introduction to its theory, Emmerich Wilhelm, "Heat Capacities: Introduction, Concepts, and Selected Applications" (Chapter 1, pp. 1–27), chapters on traditional and more contemporary experimental methods such as photoacoustic methods, e.g., Jan Thoen & Christ Glorieux, "Photothermal Techniques for Heat Capacities," and chapters on newer research interests, including on the heat capacities of proteins and other polymeric systems (Chs. 16, 15), of liquid crystals (Ch. 17), etc.

External links

- (2012-05may-24) Phonon theory sheds light on liquid thermodynamics, heat capacity – Physics World The phonon theory of liquid thermodynamics | Scientific Reports

and

and  , respectively; their quotient

, respectively; their quotient  is the

is the  or

or  , is the heat capacity

, is the heat capacity  of a sample of the substance, divided by the mass

of a sample of the substance, divided by the mass  of the sample:

of the sample:

where

where

.

.

applied to it. Therefore, it should be considered a function

applied to it. Therefore, it should be considered a function  of those two variables.

of those two variables.

and approximates the specific heat capacity by a constant

and approximates the specific heat capacity by a constant  and

and  , where

, where  is the

is the  . That is, approximately,

. That is, approximately,

(at 15 °C, 1 atm), which is

(at 15 °C, 1 atm), which is  . That is the value expected from the

. That is the value expected from the

is the

is the  is the

is the  is

is

and

and  are

are

is the mass of the body,

is the mass of the body, is the density of the material.

is the density of the material. ) or

) or  ) processes. The corresponding specific heat capacities are expressed as

) processes. The corresponding specific heat capacities are expressed as

, the

, the  . Of course, from the above relationships, for solids one writes

. Of course, from the above relationships, for solids one writes

is expressed as

is expressed as  .

.

) or

) or  ) processes. The corresponding specific heat capacities are expressed as

) processes. The corresponding specific heat capacities are expressed as

, the

, the

, measured in

, measured in

and temperature

and temperature  , where

, where  of the material's

of the material's  .) Like

.) Like  is an intensive property of the material and its state, that does not depend on the amount of substance in the sample.

is an intensive property of the material and its state, that does not depend on the amount of substance in the sample.

The function

The function  depends on the material under consideration. The

depends on the material under consideration. The  of these state variables, that is also specific of the material. The total internal energy in the sample then will be

of these state variables, that is also specific of the material. The total internal energy in the sample then will be  .

.

and even the specific internal energy

and even the specific internal energy  In general, these functions must be determined experimentally for each substance.

In general, these functions must be determined experimentally for each substance.

in the total internal energy

in the total internal energy  must be matched by the net flow of heat energy

must be matched by the net flow of heat energy  , where

, where  is the change in the sample's volume in that infinitesimal step. Therefore

is the change in the sample's volume in that infinitesimal step. Therefore

is zero (no mechanical work is done). Then, dividing by

is zero (no mechanical work is done). Then, dividing by

. An infinitesimal change in the specific enthalpy will then be

. An infinitesimal change in the specific enthalpy will then be

of the material.

of the material.

are constrained by the equation of state and the specific internal energy function. Namely,

are constrained by the equation of state and the specific internal energy function. Namely,

denotes the (partial) derivative of the state equation

denotes the (partial) derivative of the state equation  in question. The other partial derivatives are defined in the same way. These two equations on the four infinitesimal increments normally constrain them to a two-dimensional linear subspace space of possible infinitesimal state changes, that depends on the material and on the state. The constant-volume and constant-pressure changes are only two particular directions in this space.

in question. The other partial derivatives are defined in the same way. These two equations on the four infinitesimal increments normally constrain them to a two-dimensional linear subspace space of possible infinitesimal state changes, that depends on the material and on the state. The constant-volume and constant-pressure changes are only two particular directions in this space.

the function that describes how the pressure varies with the temperature

the function that describes how the pressure varies with the temperature  be the function that describes how the specific volume varies with the temperature, when the pressure is kept constant at

be the function that describes how the specific volume varies with the temperature, when the pressure is kept constant at  and

and

. In other words, the graphs of

. In other words, the graphs of

.

.

of the heat capacity at constant pressure to heat capacity at constant volume. It is sometimes also known as the isentropic expansion factor.

of the heat capacity at constant pressure to heat capacity at constant volume. It is sometimes also known as the isentropic expansion factor.