| Mathematical analysis → Complex analysis |

| Complex analysis |

|---|

|

| Complex numbers |

| Complex functions |

| Basic theory |

| Geometric function theory |

| People |

In complex analysis, a branch of mathematics, Morera's theorem, named after Giacinto Morera, gives an important criterion for proving that a function is holomorphic.

Morera's theorem states that a continuous, complex-valued function f defined on an open set D in the complex plane that satisfies for every closed piecewise C curve in D must be holomorphic on D.

The assumption of Morera's theorem is equivalent to f having an antiderivative on D.

The converse of the theorem is not true in general. A holomorphic function need not possess an antiderivative on its domain, unless one imposes additional assumptions. The converse does hold e.g. if the domain is simply connected; this is Cauchy's integral theorem, stating that the line integral of a holomorphic function along a closed curve is zero.

The standard counterexample is the function f(z) = 1/z, which is holomorphic on C − {0}. On any simply connected neighborhood U in C − {0}, 1/z has an antiderivative defined by L(z) = ln(r) + iθ, where z = re. Because of the ambiguity of θ up to the addition of any integer multiple of 2π, any continuous choice of θ on U will suffice to define an antiderivative of 1/z on U. (It is the fact that θ cannot be defined continuously on a simple closed curve containing the origin in its interior that is the root of why 1/z has no antiderivative on its entire domain C − {0}.) And because the derivative of an additive constant is 0, any constant may be added to the antiderivative and the result will still be an antiderivative of 1/z.

In a certain sense, the 1/z counterexample is universal: For every analytic function that has no antiderivative on its domain, the reason for this is that 1/z itself does not have an antiderivative on C − {0}.

Proof

There is a relatively elementary proof of the theorem. One constructs an anti-derivative for f explicitly.

Without loss of generality, it can be assumed that D is connected. Fix a point z0 in D, and for any , let be a piecewise C curve such that and . Then define the function F to be

To see that the function is well-defined, suppose is another piecewise C curve such that and . The curve (i.e. the curve combining with in reverse) is a closed piecewise C curve in D. Then,

And it follows that

Then using the continuity of f to estimate difference quotients, we get that F′(z) = f(z). Had we chosen a different z0 in D, F would change by a constant: namely, the result of integrating f along any piecewise regular curve between the new z0 and the old, and this does not change the derivative.

Since f is the derivative of the holomorphic function F, it is holomorphic. The fact that derivatives of holomorphic functions are holomorphic can be proved by using the fact that holomorphic functions are analytic, i.e. can be represented by a convergent power series, and the fact that power series may be differentiated term by term. This completes the proof.

Applications

Morera's theorem is a standard tool in complex analysis. It is used in almost any argument that involves a non-algebraic construction of a holomorphic function.

Uniform limits

For example, suppose that f1, f2, ... is a sequence of holomorphic functions, converging uniformly to a continuous function f on an open disc. By Cauchy's theorem, we know that for every n, along any closed curve C in the disc. Then the uniform convergence implies that for every closed curve C, and therefore by Morera's theorem f must be holomorphic. This fact can be used to show that, for any open set Ω ⊆ C, the set A(Ω) of all bounded, analytic functions u : Ω → C is a Banach space with respect to the supremum norm.

Infinite sums and integrals

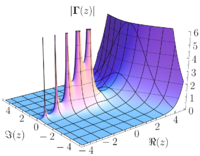

Morera's theorem can also be used in conjunction with Fubini's theorem and the Weierstrass M-test to show the analyticity of functions defined by sums or integrals, such as the Riemann zeta function or the Gamma function

Specifically one shows that for a suitable closed curve C, by writing and then using Fubini's theorem to justify changing the order of integration, getting

Then one uses the analyticity of α ↦ x to conclude that and hence the double integral above is 0. Similarly, in the case of the zeta function, the M-test justifies interchanging the integral along the closed curve and the sum.

Weakening of hypotheses

The hypotheses of Morera's theorem can be weakened considerably. In particular, it suffices for the integral to be zero for every closed (solid) triangle T contained in the region D. This in fact characterizes holomorphy, i.e. f is holomorphic on D if and only if the above conditions hold. It also implies the following generalisation of the aforementioned fact about uniform limits of holomorphic functions: if f1, f2, ... is a sequence of holomorphic functions defined on an open set Ω ⊆ C that converges to a function f uniformly on compact subsets of Ω, then f is holomorphic.

See also

- Cauchy–Riemann equations

- Methods of contour integration

- Residue (complex analysis)

- Mittag-Leffler's theorem

References

- Ahlfors, Lars (January 1, 1979), Complex Analysis, International Series in Pure and Applied Mathematics, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-000657-7, Zbl 0395.30001.

- Conway, John B. (1973), Functions of One Complex Variable I, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 11, Springer Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-90328-4, Zbl 0277.30001.

- Greene, Robert E.; Krantz, Steven G. (2006), Function Theory of One Complex Variable, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, vol. 40, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-8218-3962-4

- Morera, Giacinto (1886), "Un teorema fondamentale nella teorica delle funzioni di una variabile complessa", Rendiconti del Reale Instituto Lombardo di Scienze e Lettere (in Italian), 19 (2): 304–307, JFM 18.0338.02.

- Rudin, Walter (1987) , Real and Complex Analysis (3rd ed.), McGraw-Hill, pp. xiv+416, ISBN 978-0-07-054234-1, Zbl 0925.00005.

External links

- "Morera theorem", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Morera's Theorem". MathWorld.

for every closed piecewise C curve

for every closed piecewise C curve  in D must be holomorphic on D.

in D must be holomorphic on D.

, let

, let  be a piecewise C curve such that

be a piecewise C curve such that  and

and  . Then define the function F to be

. Then define the function F to be

is another piecewise C curve such that

is another piecewise C curve such that  and

and  . The curve

. The curve  (i.e. the curve combining

(i.e. the curve combining  in reverse) is a closed piecewise C curve in D. Then,

in reverse) is a closed piecewise C curve in D. Then,

for every n, along any closed curve C in the disc. Then the uniform convergence implies that

for every n, along any closed curve C in the disc. Then the uniform convergence implies that

for every closed curve C, and therefore by Morera's theorem f must be holomorphic. This fact can be used to show that, for any

for every closed curve C, and therefore by Morera's theorem f must be holomorphic. This fact can be used to show that, for any  or the

or the

for a suitable closed curve C, by writing

for a suitable closed curve C, by writing

and then using Fubini's theorem to justify changing the order of integration, getting

and then using Fubini's theorem to justify changing the order of integration, getting

and hence the double integral above is 0. Similarly, in the case of the zeta function, the M-test justifies interchanging the integral along the closed curve and the sum.

and hence the double integral above is 0. Similarly, in the case of the zeta function, the M-test justifies interchanging the integral along the closed curve and the sum.

to be zero for every closed (solid) triangle T contained in the region D. This in fact

to be zero for every closed (solid) triangle T contained in the region D. This in fact