| Mowry massacres | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Apache Wars, American Civil War | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

| Apache | ||||

| Engagements in Confederate Arizona | |

|---|---|

The Mowry massacres, also known as the Mowry murders, were a series of Apache attacks in and around the mining town of Mowry, Arizona between 1863 and 1865. At least sixteen American settlers were killed during the period.

Background

Former United States Army Lieutenant Sylvester Mowry purchased the Patagonia mine in 1860 from a party of Mexicans. Soon after, Mowry began operating the mine and attracted miners to the area for work. The Chiricahua and other Apache bands were also attracted though, and they considered the Santa Rita Mountains to be sacred ground, and they defended it accordingly by raiding and ambushing settlers. As the American Civil War began, United States Army troops were withdrawn from the frontier of Arizona to fight the Confederates in the South. This left the settlers unprotected and vulnerable to attack, even after Union troops from California arrived.

First attack

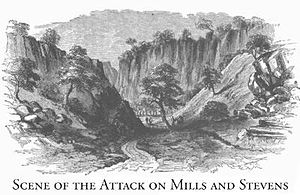

Writer and explorer John Ross Browne visited the area in early 1864, and he described the situation in his book "Adventures in the Apache Country." According to Browne, early in the morning on December 29, 1863, two young men named J.B. Mills and Edwin Stevens were traveling on the trail to the Mowry Mine, both were employees of Mowry. Two young Mexican boys were traveling nearby and discovered Apache tracks, after which they saw Mills and Stevens riding to the entrance of the canyon. The boys suspected an attack so they shouted "Los Apaches" at the riders but they did not hear. The Mills and Stevens were about four miles away from the settlement when they were attacked by the Apaches hiding in the bushes at the entrance of a canyon. Several shots were fired in rapid succession, and Stevens was killed and fell off his horse. Mills was armed so he fought the Apache until bleeding to death from his wounds. After hearing the massacre, the boys turned around and rushed back to Mowry where a four-man posse was formed and sent to the canyon within minutes but by that time it was already to late and the Apaches had escaped.

Browne visited the canyon 31 days after the attack. He reported that signs of struggle were still visible: broken arrows were found lying on the path, some of them bloodied. In Browne's account both men were badly mutilated; Stevens was pierced with a spear many times after his death, and Mills' body revealed seventeen separate wounds from arrows, musket balls and spears.

Second attack

Browne describes a second massacre at the same site almost two years later in 1865. A doctor named Titus who lived and worked at the Mowry Mine was killed at the canyon along with a Delaware Native American who was guiding him. The guide was killed at the first volley of muskets and arrows which left Titus alone, so he dismounted from his horse and fought his way 200 yards through the canyon until being shot from a hidden native in the hip with an arrow. The doctor fell to the ground, and instead of being hung from a tree and burned alive, which was a usual Apache method of torture, Titus shot himself in the head with his revolver. The Apache chief who was present spared the doctor's body from mutilation because he had shown incredible bravery in the fight.

Aftermath

Browne wrote that at Mowry, of the seventeen plots in the graveyard, fifteen of the dead were victims of Apache attacks while only two died of natural causes.

Sylvester Mowry was arrested during this period by the Union General James H. Carleton. He was charged with selling lead to rebels but was later released after convincing his judge that he was only aiding fellow settlers in their defense against the natives. The mining town was eventually destroyed by the Apache but was later repopulated.

See also

Notes

References

- Browne, R. John (1869). Adventures in the Apache County: a tour through Arizona and Sonora with notes on the silver regions of Nevada. New York: Harpers&Brothers Publishers.

- Native American history of Arizona

- Massacres of the Apache Wars

- Massacres of the American Civil War

- Massacres by Native Americans

- 1863 in Arizona Territory

- 1864 in Arizona Territory

- 1865 in Arizona Territory

- Massacres in 1863

- Massacres in 1864

- Massacres in 1865

- 1863 murders in the United States

- 1864 murders in the United States

- 1865 murders in the United States

- Murder in Arizona

- Arizona in the American Civil War