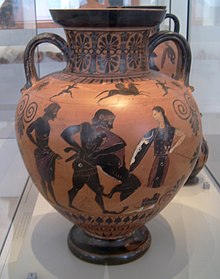

The Neck Amphora by Exekias is a neck amphora in the black figure style by the Attic vase painter and potter Exekias. It is found in the possession of the Antikensammlung Berlin under the inventory number F 1720 and is on display in the Altes Museum. It depicts Herakles' battle with the Nemean lion on one side and the sons of Theseus on the other (their earliest appearance in Athenian art). The amphora could only be restored for the first time almost a hundred and fifty years after its original discovery due to negligence and political difficulties.

Description

The clay neck amphora is 40.5 cm high. It is dated to around 545/0 BC and is executed in the black figure style, which was still common at the time. The painter Exekias was a master of this style, which he brought to its peak. He added his own innovations and modifications which appear in part also in the amphora. The vase is fragmentary, but large portions survive. Conspicuous absences include the loss of one of the two handles, and a pair of sherds from the body of the vase. The surviving pieces are in good condition.

Both sides of the amphora's belly are framed above and below by chains of painted and stylisted lotus flowers and buds. The area around the handles is decorated with volutes and palmettes. The scenes on each side are of similar size and are not divided into a front main image and a reversed opposite on the reverse as in later times. On the edge of the mouth there is a signature of Exekias, the most well-known Attic vase painter and potter, which reads ΕΞΣΕΚΙΑΣ ΕΓΡΑΦΣΕ ΚΑ ΠΟΕΣΕ ΜΕ, "Exekias painted and made me."

On one side the battle between Herakles and the Nemean lion is depicted – one of the twelve labours which the son of Zeus had to perform in the service of King Eurystheus. Herakles strangles the lion, whose skin could not be wounded, while his brother Iolaos and the goddess Athena look on, serving to frame the scene. The naked Herakles has his left arm on the neck of the lion and holds the paw of the lion in his right hand. The lion is attempting to free itself from the hero's grip. Many details are indicated in red paint, like Iolaos' beard, Athena's shield and details of the lion's mane. On the other side of the vase is a depiction of the two sons of Theseus, Akamas and Demophon with their horses, which are named by inscriptions (just like the sons) as Kalliphora and Phalios. Between the two horses, which are led to the right by their masters, is a vertical Kalos inscription, reading ΟΝΕΤΟΡΙΔΕΣ ΚΑΛΟΣ, "Onetorides is gorgeous". Both men carry a large round shield on their backs and two spears over their shoulders. The shields are detailed in white paint. Their helmets have high plumes painted in red. The sons of Theseus are presumably departing to fight in the Trojan War.

The scenes can be understood as combining two Greek regions which frequently interacted with each other: Herakles is the hero of the Peloponnese, while Theseus' sons represent the Athenians' conception of themselves. This vase marks the first appearance of the sons of Theseus in Attic art. The scene from the outbreak of the Trojan War stresses increasing Athenian self-importance. The participation of their heroes in the legendary Trojan War symbolically placed Athens on the same level as the traditionally important city-states of the Peloponnese, including the leading power of the time, Sparta. In subsequent Athenian art, the sons of Theseus were symbols of the new self-consciousness of the Athenian aristocracy.

Discovery and restoration

In addition to the art historical significance of the vase, the fate of the amphora and its individual sherds since its discovery is also of archaeological-historical significance. The vase was found in the Etruscan necropolis of Ponte dell' Abbadia near Vulci. In Athens, vases were produced largely for export to Etruria, where they were often used as grave goods. Thus, several works of Exekias have been found in Etruscan cemeteries. When the amphora was discovered in one of the Etruscan graves at Vulci which had been under excavation from 1828, it was already broken and was probably no longer complete. The sherds that were discovered were not very carefully collected. The reconstruction of the vase from its sherds was, by modern standards, faulty. As was common in the mid-nineteenth century, missing pieces were replaced and repainted to create the appearance of a complete work. After the restoration, the amphora came into the possession of the painter Eduard Magnus. The sale of smaller archaeological discoveries was common at the time, particularly when no other, more expensive and higher valued artworks (statuary or precious metals) could be found. Together with the painter's other pieces (known as the Dorow-Magnus Collection), the amphora soon entered the newly founded Museum at Lustgarten, in 1831. It stayed, with other items of portable art, in the semi-basement of the museum. According to Jakob Andreas Konrad Levezow's 1834 exhibition catalogue, the vase stood on one of the glass tables placed in a prominent position. When the portable art collection was transferred to the Neue Galerie New York, Exekias' Amphora was taken there as well.

In the 1920s, the amphoras had to be restored for reasons which are no longer known. In the process, the retouching and additions from the original restoration were largely removed. The additions were now made clearly distinct from the original sherds. Due to the war, the amphora was inventoried as "Berlin F 1720" and stored in box 167 in the Zoobunker. In 1945, the box was taken to the Soviet Union as booty. As part of the return of art to the DDR, the amphora was brought back to the Antikensammlung Berlin (unlike many other pieces from box 167) in 1958, which was now divided between East and West Berlin. The Exekian Neck Amphora was one of the few vases which came into the possession of the East Berlin Pergamonmuseum, since the majority of the vases had been kept in the magazin before the war and were hence stored in a different location during the war and ended up in the West Berlin Antikensammlung in Charlottenburg afterwards. The amphora was on display as part of the regular exhibition of the museum.

In the 1970s, the archaeologist Erika Kunze-Götte found a two-piece fragment during work on a volume of the Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum in Munich which she suggested belonged to the Exekias neck amphora. As a result, a lively correspondence sprung up between Munich and East Berlin. Photos and line drawings were exchanged and measurements were produced. A silicon cast finally confirmed that the pieces belonged. Probably the individual sherds were excavated later than the rest of the amphora or mistakenly not connected with it. There was a question of whether the museums ought to carry out an exchange or make a loan agreement, eventually settled in favour of the former option. In exchange for the sherds, the Staatliche Antikensammlung in Munich was to receive an ornamental-black figure/polychrome painted lid from the Pergamonmuseum. Although this was quickly agreed on an academic level, it took a significant time to formalise the agreement, since the DDR officials delayed things for seven years. On 7 January 1988, it finally came to Munich in exchange for the sherds.

After the pieces were reunited, the vase had to be restored again in 1990. Firstly they attempted to remove the modern additions and to insert the new fragment. In the process it was discovered that the earlier restoration had miscalculated the size of the gaps – they were too small. As a result, the vase had to be disassembled. This turned out to be a blessing in disguise. For instance, during the process, Priska Schilling uncovered the letter "ο" in the caption reading (Ι)ΟΛΑΟΣ under a modern layer of paint. Where a handle had been reconstructed, the original handle attachment was discovered underneath. Several incised inscriptions were found on the interior sides of sherds, such as Ο ΠΑΙΣ ΚΑΛΟΣ, "The boy is gorgeous" and ΚΑΛΟΣ, "He is gorgeous." It is suggested that this was a hoax by an earlier restorer, possibly Domenico Campanari in the first half of the nineteenth century. The restoration was completed in 1991.

Today the amphora is on display in the Altes Museum in the Lustgarten, along with the Tombstones of Exekias and an amphora from the outer circle of Group E, which was probably made in Exekias' workshop. This contemporary amphora also depicts Herakles fighting with the Nemean lion.

Bibliography

- Adolf Furtwängler. Beschreibung der Vasensammlung im Antiquarium, Berlin 1885, No. 1720.

- John D. Beazley. Attic Black-figure Vase-painters. Oxford 1956, pp. 143–144 No. 1.

- Ursula Kästner. "Ein deutsch-deutsches Vasenschicksal," EOS IX (November 1999), pp. VII-IX

- Ursula Kästner. "Amphora des Töpfers und Vasenmalers Exekias," in Andreas Scholl and Gertrud Platz-Horster (Ed.): Altes Museum. Pergamonmuseum. Die Antikensammlung., von Zabern, Mainz 2007, p. 57 ISBN 978-3-8053-2449-6

External links

References

- On the date, see the Perseus Project

- This description of the vase follows Ursula Kästner's description in the catalogue of the Antikensammlung (see Bibliography) and the vase's page on the Perseus Project

- See, for example, Frank Brommer, Herakles. Die zwölf Taten des Helden in antiker Kunst und Literatur, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1972 ISBN 3-412-90572-0

- The description of the discovery follows Ursula Kästner, "Ein deutsch-deutsches Vasenschicksal", EOS IX (November 1999), pp. VII–IX

| Greek amphorae | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Neck amphorae | |||

| Belly amphorae |

| ||

| Panathenaic amphorae | |||

52°31′10″N 13°23′54″E / 52.51944°N 13.39833°E / 52.51944; 13.39833

Categories: