Medical condition

| Acne | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acne vulgaris |

| |

| Acne vulgaris in an 18-year-old male during puberty | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Blackheads, whiteheads, pimples, oily skin, scarring |

| Complications | Anxiety, reduced self-esteem, depression, thoughts of suicide |

| Usual onset | Puberty |

| Risk factors | Genetics |

| Differential diagnosis | Folliculitis, rosacea, hidradenitis suppurativa, miliaria |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, medications, medical procedures |

| Medication | Azelaic acid, benzoyl peroxide, salicylic acid, antibiotics, birth control pills, co-cyprindiol, retinoids, isotretinoin |

| Frequency | 633 million affected (2015) |

Acne (/ˈækni/ ACK-nee), also known as acne vulgaris, is a long-term skin condition that occurs when dead skin cells and oil from the skin clog hair follicles. Typical features of the condition include blackheads or whiteheads, pimples, oily skin, and possible scarring. It primarily affects skin with a relatively high number of oil glands, including the face, upper part of the chest, and back. The resulting appearance can lead to lack of confidence, anxiety, reduced self-esteem, and, in extreme cases, depression or thoughts of suicide.

Susceptibility to acne is primarily genetic in 80% of cases. The roles of diet and cigarette smoking in the condition are unclear, and neither cleanliness nor exposure to sunlight are associated with acne. In both sexes, hormones called androgens appear to be part of the underlying mechanism, by causing increased production of sebum. Another common factor is the excessive growth of the bacterium Cutibacterium acnes, which is present on the skin.

Treatments for acne are available, including lifestyle changes, medications, and medical procedures. Eating fewer simple carbohydrates such as sugar may minimize the condition. Treatments applied directly to the affected skin, such as azelaic acid, benzoyl peroxide, and salicylic acid, are commonly used. Antibiotics and retinoids are available in formulations that are applied to the skin and taken by mouth for the treatment of acne. However, resistance to antibiotics may develop as a result of antibiotic therapy. Several types of birth control pills help prevent acne in women. Medical professionals typically reserve isotretinoin pills for severe acne, due to greater potential side effects. Early and aggressive treatment of acne is advocated by some in the medical community to decrease the overall long-term impact on individuals.

In 2015, acne affected approximately 633 million people globally, making it the eighth-most common disease worldwide. Acne commonly occurs in adolescence and affects an estimated 80–90% of teenagers in the Western world. Some rural societies report lower rates of acne than industrialized ones. Children and adults may also be affected before and after puberty. Although acne becomes less common in adulthood, it persists in nearly half of affected people into their twenties and thirties, and a smaller group continues to have difficulties in their forties.

Classification

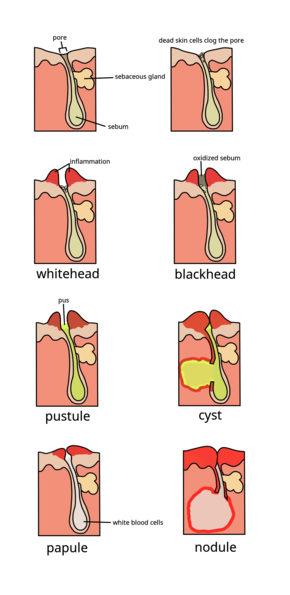

The severity of acne vulgaris (Gr. ἀκμή, "point" + L. vulgaris, "common") can be classified as mild, moderate, or severe to determine an appropriate treatment regimen. There is no universally accepted scale for grading acne severity. The presence of clogged skin follicles (known as comedones) limited to the face with occasional inflammatory lesions defines mild acne. Moderate severity acne is said to occur when a higher number of inflammatory papules and pustules occur on the face, compared to mild cases of acne, and appear on the trunk of the body. Severe acne is said to occur when nodules (the painful 'bumps' lying under the skin) are the characteristic facial lesions, and involvement of the trunk is extensive.

The lesions are usually, polymorphic, meaning they can take many forms, including open or closed comedones (commonly known as blackheads and whiteheads), papules, pustules, and even nodules or cysts so that these lesions often leave behind sequelae, or abnormal conditions resulting from a previous disease, such as scarring or hyperpigmentation.

Large nodules were previously called cysts. The term nodulocystic has been used in the medical literature to describe severe cases of inflammatory acne. True cysts are rare in those with acne, and the term severe nodular acne is now the preferred terminology.

Acne inversa (L. invertō, "upside-down") and acne rosacea (rosa, "rose-colored" + -āceus, "forming") are not forms of acne and are alternate names that respectively refer to the skin conditions hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) and rosacea. Although HS shares certain overlapping features with acne vulgaris, such as a tendency to clog skin follicles with skin cell debris, the condition otherwise lacks the hallmark features of acne and is therefore considered a distinct skin disorder.

Signs and symptoms

A severe case of nodular acne

A severe case of nodular acne Nodular acne on the back

Nodular acne on the back A typical case of a teenager with acne, pimples in various parts of the head

A typical case of a teenager with acne, pimples in various parts of the head

Typical features of acne include increased secretion of oily sebum by the skin, microcomedones, comedones, papules, nodules (large papules), pustules, and often results in scarring. The appearance of acne varies with skin color. It may result in psychological and social problems.

Scars

Acne scars are caused by inflammation within the dermis and are estimated to affect 95% of people with acne vulgaris. Abnormal healing and dermal inflammation create the scar. Scarring is most likely to take place with severe acne but may occur with any form of acne vulgaris. Acne scars are classified based on whether the abnormal healing response following dermal inflammation leads to excess collagen deposition or loss at the site of the acne lesion.

Atrophic acne scars have lost collagen from the healing response and are the most common type of acne scar (accounting for approximately 75% of all acne scars). Ice-pick scars, boxcar scars, and rolling scars are subtypes of atrophic acne scars. Boxcar scars are round or ovoid indented scars with sharp borders and vary in size from 1.5–4 mm across. Ice-pick scars are narrow (less than 2 mm across), deep scars that extend into the dermis. Rolling scars are broader than ice-pick and boxcar scars (4–5 mm across) and have a wave-like pattern of depth in the skin.

Hypertrophic scars are uncommon and are characterized by increased collagen content after the abnormal healing response. They are described as firm and raised from the skin. Hypertrophic scars remain within the original margins of the wound, whereas keloid scars can form scar tissue outside of these borders. Keloid scars from acne occur more often in men and people with darker skin, and usually occur on the trunk of the body.

Pigmentation

After an inflamed nodular acne lesion resolves, it is common for the skin to darken in that area, which is known as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH). The inflammation stimulates specialized pigment-producing skin cells (known as melanocytes) to produce more melanin pigment, which leads to the skin's darkened appearance. PIH occurs more frequently in people with darker skin color. Pigmented scar is a common term used for PIH, but is misleading as it suggests the color change is permanent. Often, PIH can be prevented by avoiding any aggravation of the nodule and can fade with time. However, untreated PIH can last for months, years, or even be permanent if deeper layers of skin are affected. Even minimal skin exposure to the sun's ultraviolet rays can sustain hyperpigmentation. Daily use of SPF 15 or higher sunscreen can minimize such a risk. Whitening agents like azelaic acid, arbutin or else may be used to improve hyperpigmentation.

Causes

Risk factors for the development of acne, other than genetics, have not been conclusively identified. Possible secondary contributors include hormones, infections, diet, and stress. Studies investigating the impact of smoking on the incidence and severity of acne have been inconclusive. Cleanliness (hygiene) and sunlight are not associated with acne.

Genes

Acne appears to be highly heritable; genetics explain 81% of the variation in the population. Studies performed in affected twins and first-degree relatives further demonstrate the strongly inherited nature of acne. Acne susceptibility is likely due to the influence of multiple genes, as the disease does not follow a classic (Mendelian) inheritance pattern. These gene candidates include certain variations in tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), IL-1 alpha, and CYP1A1 genes, among others. The 308 G/A single nucleotide polymorphism variation in the gene for TNF is associated with an increased risk for acne. Acne can be a feature of rare genetic disorders such as Apert's syndrome. Severe acne may be associated with XYY syndrome.

Hormones

Hormonal activity, such as occurs during menstrual cycles and puberty, may contribute to the formation of acne. During puberty, an increase in sex hormones called androgens causes the skin follicle glands to grow larger and make more oily sebum. The androgen hormones testosterone, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) are all linked to acne. High levels of growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) are also associated with worsened acne. Both androgens and IGF-1 seem to be essential for acne to occur, as acne does not develop in individuals with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) or Laron syndrome (insensitivity to GH, resulting in very low IGF-1 levels).

Medical conditions that commonly cause a high-androgen state, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and androgen-secreting tumors, can cause acne in affected individuals. Conversely, people who lack androgenic hormones or are insensitive to the effects of androgens rarely have acne. Pregnancy can increase androgen levels, and consequently, oily sebum synthesis. Acne can be a side effect of testosterone replacement therapy or anabolic steroid use. Over-the-counter bodybuilding and dietary supplements often contain illegally added anabolic steroids.

Infections

The anaerobic bacterial species Cutibacterium acnes (formerly Propionibacterium acnes) contributes to the development of acne, but its exact role is not well understood. There are specific sub-strains of C. acnes associated with normal skin and others with moderate or severe inflammatory acne. It is unclear whether these undesirable strains evolve on-site or are acquired, or possibly both depending on the person. These strains have the capability of changing, perpetuating, or adapting to the abnormal cycle of inflammation, oil production, and inadequate sloughing of dead skin cells from acne pores. Infection with the parasitic mite Demodex is associated with the development of acne. It is unclear whether eradication of the mite improves acne.

Diet

High-glycemic-load diets have been found to have different degrees of effect on acne severity. Multiple randomized controlled trials and nonrandomized studies have found a lower-glycemic-load diet to be effective in reducing acne. There is weak observational evidence suggesting that dairy milk consumption is positively associated with a higher frequency and severity of acne. Milk contains whey protein and hormones such as bovine IGF-1 and precursors of dihydrotestosterone. Studies suggest these components promote the effects of insulin and IGF-1 and thereby increase the production of androgen hormones, sebum, and promote the formation of comedones. Available evidence does not support a link between eating chocolate or salt and acne severity. Few studies have examined the relationship between obesity and acne. Vitamin B12 may trigger skin outbreaks similar to acne (acneiform eruptions), or worsen existing acne when taken in doses exceeding the recommended daily intake.

Stress

There are few high-quality studies to demonstrate that stress causes or worsens acne. Despite being controversial, some research indicates that increased acne severity is associated with high stress levels in certain contexts, such as hormonal changes seen in premenstrual syndrome.

Other

Some individuals experience severe intensification of their acne when they are exposed to hot humid climates; this is due to bacteria and fungus thriving in warm, moist environments. This climate-induced acne exacerbation has been termed tropical acne. Mechanical obstruction of skin follicles with helmets or chinstraps can worsen pre-existing acne. However, acne caused by mechanical obstruction is technically not acne vulgaris, but another acneiform eruption known as acne mechanica.

Several medications can also worsen pre-existing acne; this condition is the acne medicamentosa form of acne. Examples of such medications include lithium, hydantoin, isoniazid, glucocorticoids, iodides, bromides, and testosterone. When acne medicamentosa is specifically caused by anabolic–androgenic steroids it can simply be referred to as steroid acne.

Genetically susceptible individuals can get acne breakouts as a result of polymorphous light eruption; a condition triggered by sunlight and artificial UV light exposure. This form of acne is called Acne aestivalis and is specifically caused by intense UVA light exposure. Affected individuals usually experience seasonal acne breakouts on their upper arms, shoulder girdle, back, and chest. The breakouts typically occur one-to-three days after exposure to intese UVA radiation. Unlike other forms of acne, the condition spares the face; this could possibly be a result of the pathogenesis of polymorphous light eruption, in which areas of the skin that are newly exposed to intense ultraviolet radiation are affected. Since faces are typically left uncovered at all stages of life, there is little-to-no likelihood for an eruption to appear there. Studies show that both polymorphous light eruption outbreaks and the acne aestivalis breakout response can be prevented by topical antioxidants combined with the application of a broad spectrum sunscreen.

Pathophysiology

Acne vulgaris is a chronic skin disease of the pilosebaceous unit and develops due to blockages in the skin's hair follicles.

Traditionally seen as a disease of adolescence, acne vulgaris is also observed in adults, including post-menopausal women. Acne vulgaris manifested in adult female is called adult female acne (AFA), defined as a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit. Particularly in AFA, during the menopausal transition, a relative increase in androgen levels occurs as estrogen levels begin to decline, so that this hormonal shift can manifest as acne; while most women with AFA exhibit few acne lesions and have normal androgen levels, baseline investigations, including an androgen testing panel, can help rule out associated comorbidities such as polycystic ovarian syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, or tumors.

The blockages in the skin's hair follicles that cause acne vulgaris manifestations occur as a result of the following four abnormal processes: increased oily sebum production (influenced by androgens), excessive deposition of the protein keratin leading to comedo formation, colonization of the follicle by Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes) bacteria, and the local release of pro-inflammatory chemicals in the skin.

The earliest pathologic change is the formation of a plug (a microcomedone), which is driven primarily by excessive growth, reproduction, and accumulation of skin cells in the hair follicle. In healthy skin, the skin cells that have died come up to the surface and exit the pore of the hair follicle. In people with acne, the increased production of oily sebum causes the dead skin cells to stick together. The accumulation of dead skin cell debris and oily sebum blocks the pore of the hair follicle, thus forming the microcomedone. The C. acnes biofilm within the hair follicle worsens this process. If the microcomedone is superficial within the hair follicle, the skin pigment melanin is exposed to air, resulting in its oxidation and dark appearance (known as a blackhead or open comedo). In contrast, if the microcomedone occurs deep within the hair follicle, this causes the formation of a whitehead (known as a closed comedo).

The main hormonal driver of oily sebum production in the skin is dihydrotestosterone. Another androgenic hormone responsible for increased sebaceous gland activity is DHEA-S. The adrenal glands secrete higher amounts of DHEA-S during adrenarche (a stage of puberty), and this leads to an increase in sebum production. In a sebum-rich skin environment, the naturally occurring and largely commensal skin bacterium C. acnes readily grows and can cause inflammation within and around the follicle due to activation of the innate immune system. C. acnes triggers skin inflammation in acne by increasing the production of several pro-inflammatory chemical signals (such as IL-1α, IL-8, TNF-α, and LTB4); IL-1α is essential to comedo formation.

C. acnes' ability to bind and activate a class of immune system receptors known as toll-like receptors (TLRs), especially TLR2 and TLR4, is a core mechanism of acne-related skin inflammation. Activation of TLR2 and TLR4 by C. acnes leads to increased secretion of IL-1α, IL-8, and TNF-α. The release of these inflammatory signals attracts various immune cells to the hair follicle, including neutrophils, macrophages, and Th1 cells. IL-1α stimulates increased skin cell activity and reproduction, which, in turn, fuels comedo development. Furthermore, sebaceous gland cells produce more antimicrobial peptides, such as HBD1 and HBD2, in response to the binding of TLR2 and TLR4.

C. acnes also provokes skin inflammation by altering the fatty composition of oily sebum. Oxidation of the lipid squalene by C. acnes is of particular importance. Squalene oxidation activates NF-κB (a protein complex) and consequently increases IL-1α levels. Additionally, squalene oxidation increases 5-lipoxygenase enzyme activity, which catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid to leukotriene B4 (LTB4). LTB4 promotes skin inflammation by acting on the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) protein. PPARα increases the activity of activator protein 1 (AP-1) and NF-κB, thereby leading to the recruitment of inflammatory T cells. C. acnes' ability to convert sebum triglycerides to pro-inflammatory free fatty acids via secretion of the enzyme lipase further explains its inflammatory properties. These free fatty acids spur increased production of cathelicidin, HBD1, and HBD2, thus leading to further inflammation.

This inflammatory cascade typically leads to the formation of inflammatory acne lesions, including papules, infected pustules, or nodules. If the inflammatory reaction is severe, the follicle can break into the deeper layers of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and cause the formation of deep nodules. The involvement of AP-1 in the aforementioned inflammatory cascade activates matrix metalloproteinases, which contribute to local tissue destruction and scar formation.

Along with the bacteria C. acnes, the bacterial species Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis) also takes a part in the physiopathology of acne vulgaris. The proliferation of S. epidermidis with C. acnes causes the formation of biofilms, which blocks the hair follicles and pores, creating an anaerobic environment under the skin. This enables for increased growth of both C. acnes and S. epidermidis under the skin. The proliferation of C. acnes causes the formation of biofilms and a biofilm matrix, making it even harder to treat the acne.

Diagnosis

Acne vulgaris is diagnosed based on a medical professional's clinical judgment. The evaluation of a person with suspected acne should include taking a detailed medical history about a family history of acne, a review of medications taken, signs or symptoms of excessive production of androgen hormones, cortisol, and growth hormone. Comedones (blackheads and whiteheads) must be present to diagnose acne. In their absence, an appearance similar to that of acne would suggest a different skin disorder. Microcomedones (the precursor to blackheads and whiteheads) are not visible to the naked eye when inspecting the skin and require a microscope to be seen. Many features may indicate that a person's acne vulgaris is sensitive to hormonal influences. Historical and physical clues that may suggest hormone-sensitive acne include onset between ages 20 and 30; worsening the week before a woman's period; acne lesions predominantly over the jawline and chin; and inflammatory/nodular acne lesions.

Several scales exist to grade the severity of acne vulgaris, but disagreement persists about the ideal one for diagnostic use. Cook's acne grading scale uses photographs to grade severity from 0 to 8, with higher numbers representing more severe acne. This scale was the first to use a standardized photographic protocol to assess acne severity; since its creation in 1979, the scale has undergone several revisions. The Leeds acne grading technique counts acne lesions on the face, back, and chest and categorizes them as inflammatory or non-inflammatory. Leeds scores range from 0 (least severe) to 10 (most severe) though modified scales have a maximum score of 12. The Pillsbury acne grading scale classifies the severity of the acne from grade 1 (least severe) to grade 4 (most severe).

Differential diagnosis

Many skin conditions can mimic acne vulgaris, and these are collectively known as acneiform eruptions. Such conditions include angiofibromas, epidermal cysts, flat warts, folliculitis, keratosis pilaris, milia, perioral dermatitis, and rosacea, among others. Age is one factor that may help distinguish between these disorders. Skin disorders such as perioral dermatitis and keratosis pilaris can appear similar to acne but tend to occur more frequently in childhood. Rosacea tends to occur more frequently in older adults. Facial redness triggered by heat or the consumption of alcohol or spicy food is also more suggestive of rosacea. The presence of comedones helps health professionals differentiate acne from skin disorders that are similar in appearance. Chloracne and occupational acne due to exposure to certain chemicals & industrial compounds, may look very similar to acne vulgaris.

Management

Many different treatments exist for acne. These include alpha hydroxy acid, anti-androgen medications, antibiotics, antiseborrheic medications, azelaic acid, benzoyl peroxide, hormonal treatments, keratolytic soaps, nicotinamide (niacinamide), retinoids, and salicylic acid. Acne treatments work in at least four different ways, including the following: reducing inflammation, hormonal manipulation, killing C. acnes, and normalizing skin cell shedding and sebum production in the pore to prevent blockage. Typical treatments include topical therapies such as antibiotics, benzoyl peroxide, and retinoids, and systemic therapies, including antibiotics, hormonal agents, and oral retinoids.

Recommended therapies for first-line use in acne vulgaris treatment include topical retinoids, benzoyl peroxide, and topical or oral antibiotics. Procedures such as light therapy and laser therapy are not first-line treatments and typically have only an add on role due to their high cost and limited evidence. Blue light therapy is of unclear benefit. Medications for acne target the early stages of comedo formation and are generally ineffective for visible skin lesions; acne generally improves between eight and twelve weeks after starting therapy.

People often view acne as a short-term condition, some expecting it to disappear after puberty. This misconception can lead to depending on self-management or problems with long-term adherence to treatment. Communicating the long-term nature of the condition and better access to reliable information about acne can help people know what to expect from treatments.

Skin care

In general, it is recommended that people with acne do not wash affected skin more than twice daily. The application of a fragrance-free moisturizer to sensitive and acne-prone skin may reduce irritation. Skin irritation from acne medications typically peaks at two weeks after onset of use and tends to improve with continued use. Dermatologists recommend using cosmetic products that specifically say non-comedogenic, oil-free, and will not clog pores.

Acne vulgaris patients, even those with oily skin, should moisturize in order to support the skin's moisture barrier since skin barrier dysfunction may contribute to acne. Moisturizers, especially ceramide-containing moisturizers, as an adjunct therapy are particularly helpful for the dry skin and irritation that commonly results from topical acne treatment. Studies show that ceramide-containing moisturizers are important for optimal skin care; they enhance acne therapy adherence and complement existing acne therapies. In a study where acne patients used 1.2% clindamycin phosphate / 2.5% benzoyl peroxide gel in the morning and applied a micronized 0.05% tretinoin gel in the evening the overwhelming majority of patients experienced no cutaneous adverse events throughout the study. It was concluded that using ceramide cleanser and ceramide moisturizing cream caused the favorable tolerability, did not interfere with the treatment efficacy, and improved adherence to the regimen. The importance of preserving the acidic mantle and its barrier functions is widely accepted in the scientific community. Thus, maintaining a pH in the range 4.5 – 5.5 is essential in order to keep the skin surface in its optimal, healthy conditions.

Diet

Causal relationship is rarely observed with diet/nutrition and dermatologic conditions. Rather, associations – some of them compelling – have been found between diet and outcomes including disease severity and the number of conditions experienced by a patient. Evidence is emerging in support of medical nutrition therapy as a way of reducing the severity and incidence of dermatologic diseases, including acne. Researchers observed a link between high glycemic index diets and acne. Dermatologists also recommend a diet low in simple sugars as a method of improving acne. As of 2014, the available evidence is insufficient to use milk restriction for this purpose.

Medications

Benzoyl peroxide

Benzoyl peroxide (BPO) is a first-line treatment for mild and moderate acne due to its effectiveness and mild side-effects (mainly skin irritation). In the skin follicle, benzoyl peroxide kills C. acnes by oxidizing its proteins through the formation of oxygen free radicals and benzoic acid. These free radicals likely interfere with the bacterium's metabolism and ability to make proteins. Additionally, benzoyl peroxide is mildly effective at breaking down comedones and inhibiting inflammation. Combination products use benzoyl peroxide with a topical antibiotic or retinoid, such as benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin and benzoyl peroxide/adapalene, respectively. Topical benzoyl peroxide is effective at treating acne.

Side effects include increased skin photosensitivity, dryness, redness, and occasional peeling. Sunscreen use is often advised during treatment, to prevent sunburn. Lower concentrations of benzoyl peroxide are just as effective as higher concentrations in treating acne but are associated with fewer side effects. Unlike antibiotics, benzoyl peroxide does not appear to generate bacterial antibiotic resistance.

Retinoids

Retinoids are medications that reduce inflammation, normalize the follicle cell life cycle, and reduce sebum production. They are structurally related to vitamin A. Studies show dermatologists and primary care doctors underprescribe them for acne. The retinoids appear to influence the cell life cycle in the follicle lining. This helps prevent the accumulation of skin cells within the hair follicle that can create a blockage. They are a first-line acne treatment, especially for people with dark-colored skin. Retinoids are known to lead to faster improvement of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Topical retinoids include adapalene, retinol, retinaldehyde, isotretinoin, tazarotene, trifarotene, and tretinoin. They often cause an initial flare-up of acne and facial flushing and can cause significant skin irritation. Generally speaking, retinoids increase the skin's sensitivity to sunlight and are therefore recommended for use at night. Tretinoin is the least expensive of the topical retinoids and is the most irritating to the skin, whereas adapalene is the least irritating but costs significantly more. Most formulations of tretinoin are incompatible for use with benzoyl peroxide. Tazarotene is the most effective and expensive topical retinoid but is usually not as well tolerated. In 2019 a tazarotene lotion formulation, marketed to be a less irritating option, was approved by the FDA. Retinol is a form of vitamin A that has similar but milder effects and is present in many over-the-counter moisturizers and other topical products.

Isotretinoin is an oral retinoid that is very effective for severe nodular acne, and moderate acne that is stubborn to other treatments. One to two months of use is typically adequate to see improvement. Acne often resolves completely or is much milder after a 4–6 month course of oral isotretinoin. After a single round of treatment, about 80% of people report an improvement, with more than 50% reporting complete remission. About 20% of people require a second course, but 80% of those report improvement, resulting in a cumulative 96% efficacy rate.

There are concerns that isotretinoin is linked to adverse effects, like depression, suicidality, and anemia. There is no clear evidence to support some of these claims. Isotretinoin has been found in some studies to be superior to antibiotics or placebo in reducing acne lesions. However, a 2018 review comparing inflammatory lesions after treatment with antibiotics or isotretinoin found no difference. The frequency of adverse events was about twice as high with isotretinoin use, although these were mostly dryness-related events. No increased risk of suicide or depression was conclusively found.

Medical authorities strictly regulate isotretinoin use in women of childbearing age due to its known harmful effects in pregnancy. For such a woman to be considered a candidate for isotretinoin, she must have a confirmed negative pregnancy test and use an effective form of birth control. In 2008, the United States started the iPLEDGE program to prevent isotretinoin use during pregnancy. iPledge requires the woman to have two negative pregnancy tests and to use two types of birth control for at least one month before isotretinoin therapy begins and one month afterward. The effectiveness of the iPledge program is controversial due to continued instances of contraception nonadherence.

Antibiotics

People may apply antibiotics to the skin or take them orally to treat acne. They work by killing C. acnes and reducing inflammation. Although multiple guidelines call for healthcare providers to reduce the rates of prescribed oral antibiotics, many providers do not follow this guidance. Oral antibiotics remain the most commonly prescribed systemic therapy for acne. Widespread broad-spectrum antibiotic overuse for acne has led to higher rates of antibiotic-resistant C. acnes strains worldwide, especially to the commonly used tetracycline (e.g., doxycycline) and macrolide antibiotics (e.g., topical erythromycin). Therefore, dermatologists prefer antibiotics as part of combination therapy and not for use alone.

Commonly used antibiotics, either applied to the skin or taken orally, include clindamycin, erythromycin, metronidazole, sulfacetamide, and tetracyclines (e.g., doxycycline or minocycline). Doxycycline 40 milligrams daily (low-dose) appears to have similar efficacy to 100 milligrams daily and has fewer gastrointestinal side effects. However, low-dose doxycycline is not FDA-approved for the treatment of acne. Antibiotics applied to the skin are typically used for mild to moderately severe acne. Oral antibiotics are generally more effective than topical antibiotics and produce faster resolution of inflammatory acne lesions than topical applications. The Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne recommends that topical and oral antibiotics are not used together.

Oral antibiotics are recommended for no longer than three months as antibiotic courses exceeding this duration are associated with the development of antibiotic resistance and show no clear benefit over shorter durations. If long-term oral antibiotics beyond three months are used, then it is recommended that benzoyl peroxide or a retinoid be used at the same time to limit the risk of C. acnes developing antibiotic resistance.

The antibiotic dapsone is effective against inflammatory acne when applied to the skin. It is generally not a first-line choice due to its higher cost and a lack of clear superiority over other antibiotics. Topical dapsone is sometimes a preferred therapy in women or for people with sensitive or darker-toned skin. It is not recommended for use with benzoyl peroxide due to the risk of causing yellow-orange skin discoloration with this combination. Minocycline is an effective acne treatment, but it is not a first-line antibiotic due to a lack of evidence that it is better than other treatments, and concerns about its safety compared to other tetracyclines.

Sarecycline is the most recent oral antibiotic developed specifically for the treatment of acne, and is FDA-approved for the treatment of moderate to severe inflammatory acne in patients nine years of age and older. It is a narrow-spectrum tetracycline antibiotic that exhibits the necessary antibacterial activity against pathogens related to acne vulgaris and a low propensity for inducing antibiotic resistance. In clinical trials, sarecycline demonstrated clinical efficacy in reducing inflammatory acne lesions as early as three weeks and reduced truncal (back and chest) acne.

Hormonal agents

In women, the use of combined birth control pills can improve acne. These medications contain an estrogen and a progestin. They work by decreasing the production of androgen hormones by the ovaries and by decreasing the free and hence biologically active fractions of androgens, resulting in lowered skin production of sebum and consequently reduce acne severity. First-generation progestins such as norethindrone and norgestrel have androgenic properties and may worsen acne. Although oral estrogens decrease IGF-1 levels in some situations, which could theoretically improve acne symptoms, combined birth control pills do not appear to affect IGF-1 levels in fertile women. Cyproterone acetate-containing birth control pills seem to decrease total and free IGF-1 levels. Combinations containing third- or fourth-generation progestins, including desogestrel, dienogest, drospirenone, or norgestimate, as well as birth control pills containing cyproterone acetate or chlormadinone acetate, are preferred for women with acne due to their stronger antiandrogenic effects. Studies have shown a 40 to 70% reduction in acne lesions with combined birth control pills. A 2014 review found that oral antibiotics appear to be somewhat more effective than birth control pills at reducing the number of inflammatory acne lesions at three months. However, the two therapies are approximately equal in efficacy at six months for decreasing the number of inflammatory, non-inflammatory, and total acne lesions. The authors of the analysis suggested that birth control pills may be a preferred first-line acne treatment, over oral antibiotics, in certain women due to similar efficacy at six months and a lack of associated antibiotic resistance. In contrast to combined birth control pills, progestogen-only birth control forms that contain androgenic progestins have been associated with worsened acne.

Antiandrogens such as cyproterone acetate and spironolactone can successfully treat acne, especially in women with signs of excessive androgen production, such as increased hairiness or skin production of sebum, or scalp hair loss. Spironolactone is an effective treatment for acne in adult women. Unlike combined birth control pills, it is not approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for this purpose. Spironolactone is an aldosterone antagonist and is a useful acne treatment due to its ability to additionally block the androgen receptor at higher doses. Alone or in combination with a birth control pill, spironolactone has shown a 33 to 85% reduction in acne lesions in women. The effectiveness of spironolactone for acne appears to be dose-dependent. High-dose cyproterone acetate alone reportedly decreases acne symptoms in women by 75 to 90% within three months. It is usually combined with an estrogen to avoid menstrual irregularities and estrogen deficiency. The medication appears to be effective in the treatment of acne in males, with one study finding that a high dosage reduced inflammatory acne lesions by 73%. However, spironolactone and cyproterone acetate's side effects in males, such as gynecomastia, sexual dysfunction, and decreased bone mineral density, generally make their use for male acne impractical.

Pregnant and lactating women should not receive antiandrogens for their acne due to a possibility of birth disorders such as hypospadias and feminization of male babies. Women who are sexually active and who can or may become pregnant should use an effective method of contraception to prevent pregnancy while taking an antiandrogen. Antiandrogens are often combined with birth control pills for this reason, which can result in additive efficacy. The FDA added a black-box warning to spironolactone about possible tumor risks based on preclinical research with very high doses (>100-fold clinical doses) and cautioned that unnecessary use of the medication should be avoided. However, several large epidemiological studies subsequently found no greater risk of tumors in association with spironolactone in humans. Conversely, strong associations of cyproterone acetate with certain brain tumors have been discovered and its use has been restricted. The brain tumor risk with cyproterone acetate is due to its strong progestogenic actions and is not related to antiandrogenic activity nor shared by other antiandrogens.

Flutamide, a pure antagonist of the androgen receptor, is effective in treating acne in women. It appears to reduce acne symptoms by 80 to 90% even at low doses, with several studies showing complete acne clearance. In one study, flutamide decreased acne scores by 80% within three months, whereas spironolactone decreased symptoms by only 40% in the same period. In a large long-term study, 97% of women reported satisfaction with the control of their acne with flutamide. Although effective, flutamide has a risk of serious liver toxicity, and cases of death in women taking even low doses of the medication to treat androgen-dependent skin and hair conditions have occurred. As such, the use of flutamide for acne has become increasingly limited, and it has been argued that continued use of flutamide for such purposes is unethical. Bicalutamide, a pure androgen receptor antagonist with the same mechanism as flutamide and with comparable or superior antiandrogenic efficacy but with a far lower risk of liver toxicity, is an alternative option to flutamide in the treatment of androgen-dependent skin and hair conditions in women.

Clascoterone is a topical antiandrogen that has demonstrated effectiveness in the treatment of acne in both males and females and was approved for clinical use for this indication in August 2020. It has shown no systemic absorption or associated antiandrogenic side effects. In a small direct head-to-head comparison, clascoterone showed greater effectiveness than topical isotretinoin. 5α-Reductase inhibitors such as finasteride and dutasteride may be useful for the treatment of acne in both males and females but have not been adequately evaluated for this purpose. Moreover, 5α-reductase inhibitors have a strong potential for producing birth defects in male babies and this limits their use in women. However, 5α-reductase inhibitors are frequently used to treat excessive facial/body hair in women and can be combined with birth control pills to prevent pregnancy. There is no evidence as of 2010 to support the use of cimetidine or ketoconazole in the treatment of acne.

Hormonal treatments for acne such as combined birth control pills and antiandrogens may be considered first-line therapy for acne under many circumstances, including desired contraception, known or suspected hyperandrogenism, acne during adulthood, acne that flares premenstrually, and when symptoms of significant sebum production (seborrhea) are co-present. Hormone therapy is effective for acne both in women with hyperandrogenism and in women with normal androgen levels.

Azelaic acid

| This section appears to contradict itself on efficacy. Please see the talk page for more information. (December 2023) |

Azelaic acid is effective for mild to moderate acne when applied topically at a 15–20% concentration. Treatment twice daily for six months is necessary, and is as effective as topical benzoyl peroxide 5%, isotretinoin 0.05%, and erythromycin 2%. Azelaic acid is an effective acne treatment due to its ability to reduce skin cell accumulation in the follicle and its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. It has a slight skin-lightening effect due to its ability to inhibit melanin synthesis. Therefore, it is useful in treating individuals with acne who are also affected by post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Azelaic acid may cause skin irritation. It is less effective and more expensive than retinoids. Azelaic acid also led to worse treatment response when compared to benzoyl peroxide. When compared to tretinoin, azelaic acid makes little or no treatment response.

Salicylic acid

Salicylic acid is a topically applied beta-hydroxy acid that stops bacteria from reproducing and has keratolytic properties. It is less effective than retinoid therapy. Salicylic acid opens obstructed skin pores and promotes the shedding of epithelial skin cells. Dry skin is the most commonly seen side effect with topical application, though darkening of the skin can occur in individuals with darker skin types.

Other medications

Topical and oral preparations of nicotinamide (the amide form of vitamin B3) are alternative medical treatments. Nicotinamide reportedly improves acne due to its anti-inflammatory properties (influencing neutrophil chemotaxis, inhibiting the release of histamine, suppressing the lymphocyte transformation test, and reducing nitric oxide synthase production induced by cytokines), its ability to suppress sebum production, and its wound healing properties. Topical and oral preparations of zinc are suggested treatments for acne; evidence to support their use for this purpose is limited. Zinc's capacities to reduce inflammation and sebum production as well as inhibit C. acnes growth are its proposed mechanisms for improving acne. Antihistamines may improve symptoms among those already taking isotretinoin due to their anti-inflammatory properties and their ability to suppress sebum production.

Hydroquinone lightens the skin when applied topically by inhibiting tyrosinase, the enzyme responsible for converting the amino acid tyrosine to the skin pigment melanin, and is used to treat acne-associated post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. By interfering with the production of melanin in the epidermis, hydroquinone leads to less hyperpigmentation as darkened skin cells are naturally shed over time. Improvement in skin hyperpigmentation is typically seen within six months when used twice daily. Hydroquinone is ineffective for hyperpigmentation affecting deeper layers of skin such as the dermis. The use of a sunscreen with SPF 15 or higher in the morning with reapplication every two hours is recommended when using hydroquinone. Its application only to affected areas lowers the risk of lightening the color of normal skin but can lead to a temporary ring of lightened skin around the hyperpigmented area. Hydroquinone is generally well-tolerated; side effects are typically mild (e.g., skin irritation) and occur with the use of a higher than the recommended 4% concentration. Most preparations contain the preservative sodium metabisulfite, which has been linked to rare cases of allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis and severe asthma exacerbations in susceptible people. In extremely rare cases, the frequent and improper application of high-dose hydroquinone has been associated with a systemic condition known as exogenous ochronosis (skin discoloration and connective tissue damage from the accumulation of homogentisic acid).

Combination therapy

Combination therapy—using medications of different classes together, each with a different mechanism of action—has been demonstrated to be a more effective approach to acne treatment than monotherapy. The use of topical benzoyl peroxide and antibiotics together is more effective than antibiotics alone. Similarly, using a topical retinoid with an antibiotic clears acne lesions faster than the use of antibiotics alone. Frequently used combinations include the following: antibiotic and benzoyl peroxide, antibiotic and topical retinoid, or topical retinoid and benzoyl peroxide. Dermatologists generally prefer combining benzoyl peroxide with a retinoid over the combination of a topical antibiotic with a retinoid. Both regimens are effective, but benzoyl peroxide does not lead to antibiotic resistance.

Pregnancy

Although sebaceous gland activity in the skin increases during the late stages of pregnancy, pregnancy has not been reliably associated with worsened acne severity. In general, topically applied medications are considered the first-line approach to acne treatment during pregnancy, as they have little systemic absorption and are therefore unlikely to harm a developing fetus. Highly recommended therapies include topically applied benzoyl peroxide (pregnancy category C) and azelaic acid (category B). Salicylic acid carries a category C safety rating due to higher systemic absorption (9–25%), and an association between the use of anti-inflammatory medications in the third trimester and adverse effects to the developing fetus including too little amniotic fluid in the uterus and early closure of the babies' ductus arteriosus blood vessel. Prolonged use of salicylic acid over significant areas of the skin or under occlusive (sealed) dressings is not recommended as these methods increase systemic absorption and the potential for fetal harm. Tretinoin (category C) and adapalene (category C) are very poorly absorbed, but certain studies have suggested teratogenic effects in the first trimester. The data examining the association between maternal topical retinoid exposure in the first trimester of pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes is limited. A systematic review of observational studies concluded that such exposure does not appear to increase the risk of major birth defects, miscarriages, stillbirths, premature births, or low birth weight. Similarly, in studies examining the effects of topical retinoids during pregnancy, fetal harm has not been seen in the second and third trimesters. Nevertheless, since rare harms from topical retinoids are not ruled out, they are not recommended for use during pregnancy due to persistent safety concerns. Retinoids contraindicated for use during pregnancy include the topical retinoid tazarotene, and oral retinoids isotretinoin and acitretin (all category X). Spironolactone is relatively contraindicated for use during pregnancy due to its antiandrogen effects. Finasteride is not recommended as it is highly teratogenic.

Topical antibiotics deemed safe during pregnancy include clindamycin, erythromycin, and metronidazole (all category B), due to negligible systemic absorption. Nadifloxacin and dapsone (category C) are other topical antibiotics that may be used to treat acne in pregnant women but have received less study. No adverse fetal events have been reported from the topical use of dapsone. If retinoids are used there is a high risk of abnormalities occurring in the developing fetus; women of childbearing age are therefore required to use effective birth control if retinoids are used to treat acne. Oral antibiotics deemed safe for pregnancy (all category B) include azithromycin, cephalosporins, and penicillins. Tetracyclines (category D) are contraindicated during pregnancy as they are known to deposit in developing fetal teeth, resulting in yellow discoloration and thinned tooth enamel. Their use during pregnancy has been associated with the development of acute fatty liver of pregnancy and is further avoided for this reason.

Procedures

Limited evidence supports comedo extraction, but it is an option for comedones that do not improve with standard treatment. Another procedure for immediate relief is the injection of a corticosteroid into an inflamed acne comedo. Electrocautery and electrofulguration are effective alternative treatments for comedones.

Light therapy is a treatment method that involves delivering certain specific wavelengths of light to an area of skin affected by acne. Both regular and laser light have been used. The evidence for light therapy as a treatment for acne is weak and inconclusive. Various light therapies appear to provide a short-term benefit, but data for long-term outcomes, and outcomes in those with severe acne, are sparse; it may have a role for individuals whose acne has been resistant to topical medications. A 2016 meta-analysis was unable to conclude whether light therapies were more beneficial than placebo or no treatment, nor the duration of benefit.

When regular light is used immediately following the application of a sensitizing substance to the skin such as aminolevulinic acid or methyl aminolevulinate, the treatment is referred to as photodynamic therapy (PDT). PDT has the most supporting evidence of all light therapy modalities. PDT treats acne by using various forms of light (e.g., blue light or red light) that preferentially target the pilosebaceous unit. Once the light activates the sensitizing substance, this generates free radicals and reactive oxygen species in the skin, which purposefully damage the sebaceous glands and kill C. acnes bacteria. Many different types of nonablative lasers (i.e., lasers that do not vaporize the top layer of the skin but rather induce a physiologic response in the skin from the light) have been used to treat acne, including those that use infrared wavelengths of light. Ablative lasers (such as CO2 and fractional types) have also been used to treat active acne and its scars. When ablative lasers are used, the treatment is often referred to as laser resurfacing because, as mentioned previously, the entire upper layers of the skin are vaporized. Ablative lasers are associated with higher rates of adverse effects compared with non-ablative lasers, with examples being post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, persistent facial redness, and persistent pain. Physiologically, certain wavelengths of light, used with or without accompanying topical chemicals, are thought to kill bacteria and decrease the size and activity of the glands that produce sebum. Disadvantages of light therapy can include its cost, the need for multiple visits, the time required to complete the procedure(s), and pain associated with some of the treatment modalities. Typical side effects include skin peeling, temporary reddening of the skin, swelling, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Dermabrasion is an effective therapeutic procedure for reducing the appearance of superficial atrophic scars of the boxcar and rolling varieties. Ice-pick scars do not respond well to treatment with dermabrasion due to their depth. The procedure is painful and has many potential side effects such as skin sensitivity to sunlight, redness, and decreased pigmentation of the skin. Dermabrasion has fallen out of favor with the introduction of laser resurfacing. Unlike dermabrasion, there is no evidence that microdermabrasion is an effective treatment for acne.

Dermal or subcutaneous fillers are substances injected into the skin to improve the appearance of acne scars. Fillers are used to increase natural collagen production in the skin and to increase skin volume and decrease the depth of acne scars. Examples of fillers used for this purpose include hyaluronic acid; poly(methyl methacrylate) microspheres with collagen; human and bovine collagen derivatives, and fat harvested from the person's own body (autologous fat transfer).

Microneedling is a procedure in which an instrument with multiple rows of tiny needles is rolled over the skin to elicit a wound healing response and stimulate collagen production to reduce the appearance of atrophic acne scars in people with darker skin color. Notable adverse effects of microneedling include post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and tram track scarring (described as discrete slightly raised scars in a linear distribution similar to a tram track). The latter is thought to be primarily attributable to improper technique by the practitioner, including the use of excessive pressure or inappropriately large needles.

Subcision is useful for the treatment of superficial atrophic acne scars and involves the use of a small needle to loosen the fibrotic adhesions that result in the depressed appearance of the scar.

Chemical peels can be used to reduce the appearance of acne scars. Mild peels include those using glycolic acid, lactic acid, salicylic acid, Jessner's solution, or a lower concentration (20%) of trichloroacetic acid. These peels only affect the epidermal layer of the skin and can be useful in the treatment of superficial acne scars as well as skin pigmentation changes from inflammatory acne. Higher concentrations of trichloroacetic acid (30–40%) are considered to be medium-strength peels and affect the skin as deep as the papillary dermis. Formulations of trichloroacetic acid concentrated to 50% or more are considered to be deep chemical peels. Medium-strength and deep-strength chemical peels are more effective for deeper atrophic scars but are more likely to cause side effects such as skin pigmentation changes, infection, and small white superficial cysts known as milia.

Alternative medicine

Researchers are investigating complementary therapies as treatment for people with acne. Low-quality evidence suggests topical application of tea tree oil or bee venom may reduce the total number of skin lesions in those with acne. Tea tree oil appears to be approximately as effective as benzoyl peroxide or salicylic acid but is associated with allergic contact dermatitis. Proposed mechanisms for tea tree oil's anti-acne effects include antibacterial action against C. acnes and anti-inflammatory properties. Numerous other plant-derived therapies have demonstrated positive effects against acne (e.g., basil oil; oligosaccharides from seaweed; however, few well-done studies have examined their use for this purpose. There is a lack of high-quality evidence for the use of acupuncture, herbal medicine, or cupping therapy for acne.

Self-care

Many over-the-counter treatments in many forms are available, which are often known as cosmeceuticals. Certain types of makeup may be useful to mask acne. In those with oily skin, a water-based product is often preferred.

Prognosis

Acne usually improves around the age of 20 but may persist into adulthood. Permanent physical scarring may occur. Rare complications from acne or its treatment include the formation of pyogenic granulomas, osteoma cutis, and acne with facial edema. Early and aggressive treatment of acne is advocated by some in the medical community to reduce the chances of these poor outcomes.

Mental health impact

There is good evidence to support the idea that acne and associated scarring negatively affect a person's psychological state, worsen mood, lower self-esteem, and are associated with a higher risk of anxiety disorders, depression, and suicidal thoughts.

Misperceptions about acne's causative and aggravating factors are common, and people with acne often blame themselves, and others often blame those with acne for their condition. Such blame can worsen the affected person's sense of self-esteem. Until the 20th century, even among dermatologists, the list of causes was believed to include excessive sexual thoughts and masturbation. Dermatology's association with sexually transmitted infections, especially syphilis, contributed to the stigma.

Another psychological complication of acne vulgaris is acne excoriée, which occurs when a person persistently picks and scratches pimples, irrespective of the severity of their acne. This can lead to significant scarring, changes in the affected person's skin pigmentation, and a cyclic worsening of the affected person's anxiety about their appearance.

Epidemiology

Globally, acne affects approximately 650 million people, or about 9.4% of the population, as of 2010. It affects nearly 90% of people in Western societies during their teenage years, but can occur before adolescence and may persist into adulthood. While acne that first develops between the ages of 21 and 25 is uncommon, it affects 54% of women and 40% of men older than 25 years of age and has a lifetime prevalence of 85%. About 20% of those affected have moderate or severe cases. It is slightly more common in females than males (9.8% versus 9.0%). In those over 40 years old, 1% of males and 5% of females still have problems.

Rates appear to be lower in rural societies. While some research has found it affects people of all ethnic groups, acne may not occur in the non-Westernized peoples of Papua New Guinea and Paraguay.

Acne affects 40–50 million people in the United States (16%) and approximately 3–5 million in Australia (23%). Severe acne tends to be more common in people of Caucasian or Amerindian descent than in people of African descent.

History

Historical records indicate that pharaohs had acne, which may be the earliest known reference to the disease. Sulfur's usefulness as a topical remedy for acne dates back to at least the reign of Cleopatra (69–30 BCE). The sixth-century Greek physician Aëtius of Amida reportedly coined the term "ionthos" (ίονθωξ,) or "acnae", which seems to be a reference to facial skin lesions that occur during "the 'acme' of life" (puberty).

In the 16th century, the French physician and botanist François Boissier de Sauvages de Lacroix provided one of the earlier descriptions of acne. He used the term "psydracia achne" to describe small, red, and hard tubercles that altered a person's facial appearance during adolescence and were neither itchy nor painful.

The recognition and characterization of acne progressed in 1776 when Josef Plenck (an Austrian physician) published a book that proposed the novel concept of classifying skin diseases by their elementary (initial) lesions. In 1808 the English dermatologist Robert Willan refined Plenck's work by providing the first detailed descriptions of several skin disorders using morphologic terminology that remains in use today. Thomas Bateman continued and expanded on Robert Willan's work as his student and provided the first descriptions and illustrations of acne accepted as accurate by modern dermatologists. Erasmus Wilson, in 1842, was the first to make the distinction between acne vulgaris and rosacea. The first professional medical monograph dedicated entirely to acne was written by Lucius Duncan Bulkley and published in New York in 1885.

Scientists initially hypothesized that acne represented a disease of the skin's hair follicle, and occurred due to blockage of the pore by sebum. During the 1880s, they observed bacteria by microscopy in skin samples from people with acne. Investigators believed the bacteria caused comedones, sebum production, and ultimately acne. During the mid-twentieth century, dermatologists realized that no single hypothesized factor (sebum, bacteria, or excess keratin) fully accounted for the disease in its entirety. This led to the current understanding that acne could be explained by a sequence of related events, beginning with blockage of the skin follicle by excessive dead skin cells, followed by bacterial invasion of the hair follicle pore, changes in sebum production, and inflammation.

The approach to acne treatment underwent significant changes during the twentieth century. Retinoids became a medical treatment for acne in 1943. Benzoyl peroxide was first proposed as a treatment in 1958 and remains a staple of acne treatment. The introduction of oral tetracycline antibiotics (such as minocycline) modified acne treatment in the 1950s. These reinforced the idea amongst dermatologists that bacterial growth on the skin plays an important role in causing acne. Subsequently, in the 1970s, tretinoin (original trade name Retin A) was found to be an effective treatment. The development of oral isotretinoin (sold as Accutane and Roaccutane) followed in 1980. After its introduction in the United States, scientists identified isotretinoin as a medication highly likely to cause birth defects if taken during pregnancy. In the United States, more than 2,000 women became pregnant while taking isotretinoin between 1982 and 2003, with most pregnancies ending in abortion or miscarriage. Approximately 160 babies were born with birth defects due to maternal use of isotretinoin during pregnancy.

Treatment of acne with topical crushed dry ice, known as cryoslush, was first described in 1907 but is no longer performed commonly. Before 1960, the use of X-rays was also a common treatment.

Society and culture

The costs and social impact of acne are substantial. In the United States, acne vulgaris is responsible for more than 5 million doctor visits and costs over US$2.5 billion each year in direct costs. Similarly, acne vulgaris is responsible for 3.5 million doctor visits each year in the United Kingdom. Sales for the top ten leading acne treatment brands in the US in 2015 amounted to $352 million.

Acne vulgaris and its resultant scars are associated with significant social and academic difficulties that can last into adulthood. During the Great Depression, dermatologists discovered that young men with acne had difficulty obtaining jobs. Until the 1930s, many people viewed acne as a trivial problem among middle-class girls because, unlike smallpox and tuberculosis, no one died from it, and a feminine problem, because boys were much less likely to seek medical assistance for it. During World War II, some soldiers in tropical climates developed such severe and widespread tropical acne on their bodies that they were declared medically unfit for duty.

Research

Efforts to better understand the mechanisms of sebum production are underway. This research aims to develop medications that target and interfere with the hormones that are known to increase sebum production (e.g., IGF-1 and alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone). Other sebum-lowering medications such as topical antiandrogens, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor modulators, and inhibitors of the stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 enzyme are also a focus of research efforts. Particles that release nitric oxide into the skin to decrease skin inflammation caused by C. acnes and the immune system have shown promise for improving acne in early clinical trials. Another avenue of early-stage research has focused on how to best use laser and light therapy to selectively destroy sebum-producing glands in the skin's hair follicles to reduce sebum production and improve acne appearance.

The use of antimicrobial peptides against C. acnes is under investigation as a treatment for acne to overcoming antibiotic resistance. In 2007, scientists reported the first genome sequencing of a C. acnes bacteriophage (PA6). The authors proposed applying this research toward the development of bacteriophage therapy as an acne treatment to overcome the problems associated with long-term antibiotic use, such as bacterial resistance. Oral and topical probiotics are under evaluation as treatments for acne. Probiotics may have therapeutic effects for those affected by acne due to their ability to decrease skin inflammation and improve skin moisture by increasing the skin's ceramide content. As of 2014, knowledge of the effects of probiotics on acne in humans was limited.

Decreased levels of retinoic acid in the skin may contribute to comedo formation. Researchers are investigating methods to increase the skin's production of retinoic acid to address this deficiency. A vaccine against inflammatory acne has shown promising results in mice and humans. Some have voiced concerns about creating a vaccine designed to neutralize a stable community of normal skin bacteria that is known to protect the skin from colonization by more harmful microorganisms.

Other animals

Acne can occur on cats, dogs, and horses.

References

- ^ Vary JC (November 2015). "Selected Disorders of Skin Appendages--Acne, Alopecia, Hyperhidrosis". The Medical Clinics of North America (Review). 99 (6): 1195–211. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.07.003. PMID 26476248.

- ^ Bhate K, Williams HC (March 2013). "Epidemiology of acne vulgaris". The British Journal of Dermatology (Review). 168 (3): 474–85. doi:10.1111/bjd.12149. PMID 23210645. S2CID 24002879.

- ^ Barnes LE, Levender MM, Fleischer AB, Feldman SR (April 2012). "Quality of life measures for acne patients". Dermatologic Clinics (Review). 30 (2): 293–300, ix. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.11.001. PMID 22284143.

- ^ Goodman G (July 2006). "Acne and acne scarring – the case for active and early intervention". Australian Family Physician. 35 (7): 503–504. PMID 16820822. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ James WD (April 2005). "Clinical practice. Acne". The New England Journal of Medicine (Review). 352 (14): 1463–72. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp033487. PMID 15814882.

- Kahan S (2008). In a Page: Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 412. ISBN 9780781770354. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017.

- ^ Mahmood SN, Bowe WP (April 2014). "[Diet and acne update: carbohydrates emerge as the main culprit]". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology (Review). 13 (4): 428–35. PMID 24719062. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ Titus S, Hodge J (15 October 2012). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Acne". American Family Physician. 86 (8): 734–740. PMID 23062156. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ GBD 2015 Disease Injury Incidence Prevalence Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ Aslam I, Fleischer A, Feldman S (March 2015). "Emerging drugs for the treatment of acne". Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs (Review). 20 (1): 91–101. doi:10.1517/14728214.2015.990373. ISSN 1472-8214. PMID 25474485. S2CID 12685388.(subscription required)

- Tuchayi SM, Makrantonaki E, Ganceviciene R, Dessinioti C, Feldman SR, Zouboulis CC (September 2015). "Acne vulgaris". Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 1: 15033. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2015.33. PMID 27227877. S2CID 44167421.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions: Acne" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Public Health and Science, Office on Women's Health. July 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ Knutsen-Larson S, Dawson AL, Dunnick CA, Dellavalle RP (January 2012). "Acne vulgaris: pathogenesis, treatment, and needs assessment". Dermatologic Clinics (Review). 30 (1): 99–106, viii–ix. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.09.001. PMID 22117871.

- ^ Schnopp C, Mempel M (August 2011). "Acne vulgaris in children and adolescents". Minerva Pediatrica (Review). 63 (4): 293–304. PMID 21909065.

- ^ Zaenglein AL (October 2018). "Acne Vulgaris". The New England Journal of Medicine (Review). 379 (14): 1343–1352. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1702493. PMID 30281982. S2CID 52914179.

- ^ Beylot C, Auffret N, Poli F, Claudel JP, Leccia MT, Del Giudice P, Dreno B (March 2014). "Propionibacterium acnes: an update on its role in the pathogenesis of acne". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (Review). 28 (3): 271–8. doi:10.1111/jdv.12224. PMID 23905540. S2CID 26027411.

- ^ Vallerand IA, Lewinson RT, Farris MS, Sibley CD, Ramien ML, Bulloch AG, Patten SB (January 2018). "Efficacy and adverse events of oral isotretinoin for acne: a systematic review". The British Journal of Dermatology. 178 (1): 76–85. doi:10.1111/bjd.15668. PMID 28542914. S2CID 635373.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, Bolliger IW, Dellavalle RP, Margolis DJ, et al. (June 2014). "The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 134 (6): 1527–1534. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.446. PMID 24166134.

- ^ Taylor M, Gonzalez M, Porter R (May–June 2011). "Pathways to inflammation: acne pathophysiology". European Journal of Dermatology (Review). 21 (3): 323–33. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1357. PMID 21609898. S2CID 7128254.

- ^ Dawson AL, Dellavalle RP (May 2013). "Acne vulgaris". The BMJ (Review). 346 (5): 30–33. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2634. JSTOR 23494950. PMID 23657180. S2CID 5331094.

- ^ Goldberg DJ, Berlin AL (October 2011). Acne and Rosacea: Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. London: Manson Pub. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-84076-150-4. Archived from the original on 2 July 2016.

- ^ Spencer EH, Ferdowsian HR, Barnard ND (April 2009). "Diet and acne: a review of the evidence". International Journal of Dermatology (Review). 48 (4): 339–47. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04002.x. PMID 19335417. S2CID 16534829.

- ^ Admani S, Barrio VR (November 2013). "Evaluation and treatment of acne from infancy to preadolescence". Dermatologic Therapy (Review). 26 (6): 462–6. doi:10.1111/dth.12108. PMID 24552409. S2CID 30549586.

- ""acne", "vulgar"". Oxford English Dictionary (CD-ROM) (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2009.

- ^ Zaenglein AL, Graber EM, Thiboutot DM (2012). "Chapter 80 Acne Vulgaris and Acneiform Eruptions". In Goldsmith, Lowell A., Katz, Stephen I., Gilchrest, Barbara A., Paller, Amy S., Lefell, David J., Wolff, Klaus (eds.). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 897–917. ISBN 978-0-07-171755-7.

- ^ Dias da Rocha MA, Saint Aroman M, Mengeaud V, Carballido F, Doat G, Coutinho A, Bagatin E (2024). "Unveiling the Nuances of Adult Female Acne: A Comprehensive Exploration of Epidemiology, Treatment Modalities, Dermocosmetics, and the Menopausal Influence". Int J Womens Health. 16: 663–678. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S431523. PMC 11034510. PMID 38650835.

- ^ Dessinioti C, Katsambas A, Antoniou C (May–June 2014). "Hidradenitis suppurrativa (acne inversa) as a systemic disease". Clinics in Dermatology (Review). 32 (3): 397–408. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.006. PMID 24767187.

- Moustafa FA, Sandoval LF, Feldman SR (September 2014). "Rosacea: new and emerging treatments". Drugs (Review). 74 (13): 1457–65. doi:10.1007/s40265-014-0281-x. PMID 25154627. S2CID 5205305.

- ^ Dessinioti C, Antoniou C, Katsambas A (January–February 2014). "Acneiform eruptions". Clinics in Dermatology (Review). 32 (1): 24–34. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.05.023. PMID 24314375.

- Adityan B, Kumari R, Thappa DM (May 2009). "Scoring systems in acne vulgaris" (PDF). Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology (Review). 75 (3): 323–6. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.51258. PMID 19439902. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Zhao YE, Hu L, Wu LP, Ma JX (March 2012). "A meta-analysis of association between acne vulgaris and Demodex infestation". Journal of Zhejiang University Science B (Meta-analysis). 13 (3): 192–202. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1100285. PMC 3296070. PMID 22374611.

- ^ Fife D (April 2016). "Evaluation of Acne Scars: How to Assess Them and What to Tell the Patient". Dermatologic Clinics (Review). 34 (2): 207–13. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.11.009. PMID 27015781.

- ^ Levy LL, Zeichner JA (October 2012). "Management of acne scarring, part II: a comparative review of non-laser-based, minimally invasive approaches". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 13 (5): 331–40. doi:10.2165/11631410-000000000-00000. PMID 22849351. S2CID 41448330.

- ^ Sánchez Viera M (July 2015). "Management of acne scars: fulfilling our duty of care for patients". The British Journal of Dermatology (Review). 172 Suppl 1 (Supplement 1): 47–51. doi:10.1111/bjd.13650. PMID 25597636.

- Sobanko JF, Alster TS (October 2012). "Management of acne scarring, part I: a comparative review of laser surgical approaches". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 13 (5): 319–30. doi:10.2165/11598910-000000000-00000. PMID 22612738. S2CID 28374672.

- ^ Chandra M, Levitt J, Pensabene CA (May 2012). "Hydroquinone therapy for post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation secondary to acne: not just prescribable by dermatologists". Acta Dermato-Venereologica (Review). 92 (3): 232–5. doi:10.2340/00015555-1225. PMID 22002814.

- ^ Yin NC, McMichael AJ (February 2014). "Acne in patients with skin of color: practical management". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 15 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1007/s40257-013-0049-1. PMID 24190453. S2CID 43211448.

- ^ Callender VD, St Surin-Lord S, Davis EC, Maclin M (April 2011). "Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: etiologic and therapeutic considerations". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 12 (2): 87–99. doi:10.2165/11536930-000000000-00000. PMID 21348540. S2CID 9997519.

- Liyanage A, Liyanage G, Sirimanna G, Schürer N (February 2022). "Comparative Study on Depigmenting Agents in Skin of Color". The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology. 15 (2): 12–17. ISSN 1941-2789. PMC 8884189. PMID 35309879.

- Rigopoulos E, Korfitis C (2014). "Acne and Smoking". In Zouboulis C, Katsambas A, Kligman AM (eds.). Pathogenesis and Treatment of Acne and Rosacea. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 167–170. ISBN 978-3-540-69374-1.

- InformedHealth.org (26 September 2019). Acne: Overview. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- Yang JK, Wu WJ, Qi J, He L, Zhang YP (February 2014). "TNF-308 G/A polymorphism and risk of acne vulgaris: a meta-analysis". PLOS ONE (Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis). 9 (2): e87806. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...987806Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087806. PMC 3912133. PMID 24498378.

- ^ Fitzpatrick TB (2005). Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Pub. Division. p. 2. ISBN 978-0071440196.

- Hoeger PH, Irvine AD, Yan AC (2011). "Chapter 79: Acne". Harper's Textbook of Pediatric Dermatology (3rd ed.). New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-4536-0.

- Shalita AR, Del Rosso JQ, Webster G, eds. (March 2011). Acne Vulgaris. CRC Press. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-1-61631-009-7. Archived from the original on 9 December 2016.

- Zouboulis CC, Katsambas AD, Kligman AM, eds. (July 2014). Pathogenesis and Treatment of Acne and Rosacea. Springer. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-3-540-69375-8. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016.

- ^ Das S, Reynolds RV (December 2014). "Recent advances in acne pathogenesis: implications for therapy". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 15 (6): 479–88. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0099-z. PMID 25388823. S2CID 28243535.

- ^ Housman E, Reynolds RV (November 2014). "Polycystic ovary syndrome: a review for dermatologists: Part I. Diagnosis and manifestations". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (Review). 71 (5): 847.e1–847.e10, quiz 857–8. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.05.007. PMID 25437977.

- ^ Kong YL, Tey HL (June 2013). "Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation". Drugs (Review). 73 (8): 779–87. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0. PMID 23657872. S2CID 45531743.

- Melnik B, Jansen T, Grabbe S (February 2007). "Abuse of anabolic-androgenic steroids and bodybuilding acne: an underestimated health problem". Journal of the German Society of Dermatology (Review). 5 (2): 110–7. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06176.x. PMID 17274777. S2CID 13382470.

- Joseph JF, Parr MK (January 2015). "Synthetic androgens as designer supplements". Current Neuropharmacology (Review). 13 (1): 89–100. doi:10.2174/1570159X13666141210224756. PMC 4462045. PMID 26074745.

- ^ Simonart T (December 2013). "Immunotherapy for acne vulgaris: current status and future directions". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 14 (6): 429–35. doi:10.1007/s40257-013-0042-8. PMID 24019180. S2CID 37750291.

- ^ Bhate K, Williams HC (April 2014). "What's new in acne? An analysis of systematic reviews published in 2011-2012". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology (Review). 39 (3): 273–7, quiz 277–8. doi:10.1111/ced.12270. PMID 24635060. S2CID 29010884.

- ^ Bronsnick T, Murzaku EC, Rao BK (December 2014). "Diet in dermatology: Part I. Atopic dermatitis, acne, and nonmelanoma skin cancer". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (Review). 71 (6): 1039.e1–1039.e12. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.015. PMID 25454036.

- Melnik BC, John SM, Plewig G (November 2013). "Acne: risk indicator for increased body mass index and insulin resistance". Acta Dermato-Venereologica (Review). 93 (6): 644–9. doi:10.2340/00015555-1677. PMID 23975508.

- ^ Davidovici BB, Wolf R (January 2010). "The role of diet in acne: facts and controversies". Clinics in Dermatology (Review). 28 (1): 12–6. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.03.010. PMID 20082944.

- ^ Ferdowsian HR, Levin S (March 2010). "Does diet really affect acne?". Skin Therapy Letter (Review). 15 (3): 1–2, 5. PMID 20361171. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015.