| This article is missing information about details of color perception. Please expand the article to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (June 2022) |

The opponent process is a color theory that states that the human visual system interprets information about color by processing signals from photoreceptor cells in an antagonistic manner. The opponent-process theory suggests that there are three opponent channels, each comprising an opposing color pair: red versus green, blue versus yellow, and black versus white (luminance). The theory was first proposed in 1892 by the German physiologist Ewald Hering.

Color theory

Complementary colors

Main article: Complementary colorsWhen staring at a bright color for a while (e.g. red), then looking away at a white field, an afterimage is perceived, such that the original color will evoke its complementary color (green, in the case of red input). When complementary colors are combined or mixed, they "cancel each other out" and become neutral (white or gray). That is, complementary colors are never perceived as a mixture; there is no "greenish red" or "yellowish blue", despite claims to the contrary. The strongest color contrast a color can have is its complementary color. Complementary colors may also be called "opposite colors" and are understandably the basis of the colors used in the opponent process theory.

Unique hues

The colors that define the extremes for each opponent channel are called unique hues, as opposed to composite (mixed) hues. Ewald Hering first defined the unique hues as red, green, blue, and yellow, and based them on the concept that these colors could not be simultaneously perceived. For example, a color cannot appear both red and green. These definitions have been experimentally refined and are represented today by average hue angles of 353° (carmine red), 128° (cobalt green), 228° (cobalt blue), 58° (yellow).

Unique hues can differ between individuals and are often used in psychophysical research to measure variations in color perception due to color-vision deficiencies or color adaptation. While there is considerable inter-subject variability when defining unique hues experimentally, an individual's unique hues are very consistent, to within a few nanometers.

Physiological basis

Relation to LMS color space

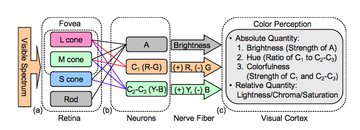

Though the trichromatic and opponent processes theories were initially thought to be at odds, it was later shown that the mechanisms responsible for the opponent process receive signals from the three types of cones predicted by the trichromatic theory and process them at a more complex level.

Most humans have three different cone cells in their retinas that facilitate trichromatic color vision. Colors are determined by the proportional excitation of these three cone types, i.e. their quantum catch. The levels of excitation of each cone type are the parameters that define LMS color space. To calculate the opponent process tristimulus values from the LMS color space, the cone excitations must be compared:

- The luminous opponent channel is equal to the sum of all three cone cells (plus the rod cells in some conditions).

- The red–green opponent channel is equal to the difference of the L- and M-cones.

- The blue–yellow opponent channel is equal to the difference of the S-cone and the sum of the L- and M-cones.

Neurological basis

See also: Lateral geniculate nucleus § Color processing

The neurological conversion of color from LMS color space to the opponent process is believed to take place mostly in the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of the thalamus, though it may also take place in the retina bipolar cells. Retinal ganglion cells carry the information from the retina to the LGN, which contains three major classes of layers:

- Magnocellular layers (large-cell) – responsible largely for the luminance channel

- Parvocellular layers (small-cell) – responsible largely for red–green opponency

- Koniocellular layers – responsible largely for blue–yellow opponency

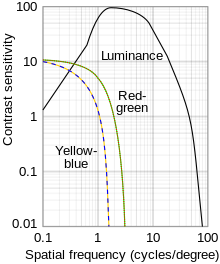

Advantage

Transmitting information in opponent-channel color space is advantageous over transmitting it in LMS color space ("raw" signals from each cone type). There is some overlap in the wavelengths of light to which the three types of cones (L for long-wave, M for medium-wave, and S for short-wave light) respond, so it is more efficient for the visual system (from a perspective of dynamic range) to record differences between the responses of cones, rather than each type of cone's individual response.

Color blindness

Main article: Color blindnessColor blindness can be classified by the cone cell that is affected (protan, deutan, tritan) or by the opponent channel that is affected (red–green or blue–yellow). In either case, the channel can either be inactive (in the case of dichromacy) or have a lower dynamic range (in the case of anomalous trichromacy). For example, individuals with deuteranopia see little difference between the red and green unique hues.

History

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe first studied the physiological effect of opposed colors in his Theory of Colours in 1810. Goethe arranged his color wheel symmetrically "for the colours diametrically opposed to each other in this diagram are those which reciprocally evoke each other in the eye. Thus, yellow demands purple; orange, blue; red, green; and vice versa: Thus again all intermediate gradations reciprocally evoke each other."

Ewald Hering proposed opponent color theory in 1892. He thought that the colors red, yellow, green, and blue are special in that any other color can be described as a mix of them, and that they exist in opposite pairs. That is, either red or green is perceived and never greenish-red: Even though yellow is a mixture of red and green in the RGB color theory, humans do not perceive it as such.

Hering's new theory ran counter to the prevailing Young–Helmholtz theory (trichromatic theory), first proposed by Thomas Young in 1802 and developed by Hermann von Helmholtz in 1850. The two theories seemed irreconcilable until 1925 when Erwin Schrödinger was able to reconcile the two theories and show that they can be complementary.

Validation

In 1957, Leo Hurvich and Dorothea Jameson provided psychophysical validation for Hering's theory. Their method was called hue cancellation. Hue cancellation experiments start with a color (e.g. yellow) and attempt to determine how much of the opponent color (e.g. blue) of one of the starting color's components must be added to reach the neutral point.

In 1959, Gunnar Svaetichin and MacNichol recorded from the retinae of fish and reported of three distinct types of cells:

- One cell responded with hyperpolarization to all light stimuli regardless of wavelength and was termed a luminosity cell.

- Another cell responded with hyperpolarization at short wavelengths and with depolarization at mid-to-long wavelengths. This was termed a chromaticity cell.

- A third cell – also a chromaticity cell – responded with hyperpolarization at fairly short wavelengths, peaking about 490 nm, and with depolarization at wavelengths longer than about 610 nm.

Svaetichin and MacNichol called the chromaticity cells yellow–blue and red–green opponent color cells.

Similar chromatically or spectrally opposed cells, often incorporating spatial opponency (e.g. red "on" center and green "off" surround), were found in the vertebrate retina and lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) through the 1950s and 1960s by De Valois et al., Wiesel and Hubel, and others.

Following Gunnar Svaetichin's lead, the cells were widely called opponent color cells: red–green and yellow–blue. Over the next three decades, spectrally opposed cells continued to be reported in primate retinae and LGN. A variety of terms are used in the literature to describe these cells, including chromatically opposed or chromatically opponent, spectrally opposed or spectrally opponent, opponent colour, colour opponent, opponent response, and simply, opponent.

In other fields

Main article: Opponent-process theoryOthers have applied the idea of opposing stimulations beyond visual systems, described in the article on opponent-process theory. In 1967, Rod Grigg extended the concept to reflect a wide range of opponent processes in biological systems. In 1970, Solomon and Corbit expanded Hurvich and Jameson's general neurological opponent process model to explain emotion, drug addiction, and work motivation.

Applications

The opponent color theory can be applied to computer vision and implemented as the Gaussian color model and the natural-vision-processing model.

Criticism and the complementary color cells

Much controversy exists over whether opponent-processing theory is the best way to explain color vision. A few experiments have been conducted involving image stabilization (where one experiences border loss) that produced results that suggest participants have seen "impossible" colors, or color combinations humans should not be able to see under the opponent-processing theory. However, many criticize that this result may just be illusionary experiences. Critics and researchers have instead started to turn to explain color vision through references to retinal mechanisms, rather than opponent processing, which happens in the brain's visual cortex.

As single-cell recordings accumulated, it became clear to many physiologists and psychophysicists that opponent colors did not satisfactorily account for single-cell spectrally opposed responses. For instance, Jameson and D’Andrade analyzed opponent-colors theory and found the unique hues did not match the spectrally opposed responses. De Valois himself summed it up: "Although we, like others, were most impressed with finding opponent cells, in accord with Hering's suggestions, when the Zeitgeist at the time was strongly opposed to the notion, the earliest recordings revealed a discrepancy between the Hering–Hurvich–Jameson opponent perceptual channels and the response characteristics of opponent cells in the macaque lateral geniculate nucleus." Valberg recalls that "it became common among neurophysiologists to use colour terms when referring to opponent cells as in the notations red-ON cells, green-OFF cells ... In the debate ... some psychophysicists were happy to see what they believed to be opponency confirmed at an objective, physiological level. Consequently, little hesitation was shown in relating the unique and polar color pairs directly to cone opponency. Despite evidence to the contrary ... textbooks have, up to this day, repeated the misconception of relating unique hue perception directly to peripheral cone opponent processes. The analogy with Hering's hypothesis has been carried even further so as to imply that each color in the opponent pair of unique colors could be identified with either excitation or inhibition of one and the same type of opponent cell." Webster et al. and Wuerger et al. have conclusively re-affirmed that single-cell spectrally opposed responses do not align with unique-hue opponent colors.

More recent experiments show that the relationship between the responses of single "color-opponent" cells and perceptual color opponency is even more complex than supposed. Experiments by Zeki et al., using the Land Color Mondrian, have shown that when normal observers view, for example, a green surface which is part of a multi-colored scene and which reflects more green than red light it looks green and its afterimage is magenta. But when the same green surface reflects more red than green light, it still looks green (because of the operation of color constancy mechanisms) and its afterimage is still perceived as magenta. This is true also of other colors and may be summarized by saying that, just as surfaces retain their color categories in spite of wide-ranging fluctuations in the wavelength-energy composition of the light reflected from them, the color of the afterimage produced by viewing surfaces also retains its color category and is therefore also independent of the wavelength-energy composition of the light reflected from the patch being viewed. There is, in other words, a constancy to the colors of afterimages. This serves to emphasize further the need to search more deeply into the relationship between the responses of single opponent cells and perceptual color opponency on the one hand and the need for a better understanding of whether physiological opponent processes generate perceptual opponent colors or whether the latter are generated after colors are generated.

In 2013, Pridmore argued that most red–green cells reported in the literature in fact code the red–cyan colors. Thus, the cells are coding complementary colors instead of opponent colors. Pridmore reported also of green–magenta cells in the retina and V1. He thus argued that the red–green and blue–yellow cells should be instead called green–magenta, red–cyan and blue–yellow complementary cells. An example of the complementary process can be experienced by staring at a red (or green) square for forty seconds, and then immediately looking at a white sheet of paper. The observer then perceives a cyan (or magenta) square on the blank sheet. This complementary color afterimage is more easily explained by the trichromatic color theory (Young–Helmholtz theory) than the traditional RYB color theory; in the opponent-process theory, fatigue of pathways promoting red produces the illusion of a cyan square.

A 2023 opinion essay of Conway, Malik-Moraleda, and Gibson claimed to "review the psychological and physiological evidence for Opponent-Colors Theory" and bluntly stated "the theory is wrong".

See also

References

- Michael Foster (1891). A Text-book of physiology. Lea Bros. & Co. p. 921.

- ^ Hering E, 1964. Outlines of a Theory of the Light Sense. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Miyahara, E. (2003). "Focal colors and unique hues". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 97 (3_suppl): 1038–1042. doi:10.2466/pms.2003.97.3f.1038. PMC 1404500. PMID 15002843.

- Tregillus, Katherine (2019). "Long-term adaptation to color". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 30: 116–121. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.07.005. S2CID 201042565.

- Mollon, J. D. (1997). "On the nature of unique hues". John Dalton's Colour Vision Legacy: 381–392.

- Kandel E. R., Schwartz J. H. and Jessell T. M., 2000. Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed., McGraw–Hill, New York. pp. 577–580.

- M. Ghodrati, S.-M. Khaligh-Razavi, S. R. Lehky, Towards building a more complex view of the lateral geniculate nucleus: recent advances in understanding its role, Prog. Neurobiol. 156:214–255, 2017.

- "Goethe's Color Theory". Vision science and the emergence of modern art. Archived from the original on 2008-09-16.

- Goethe J (1810). Theory of Colours, paragraph #50.

- "Goethe on Colours". The Art-Union. 2 (18): 107. July 15, 1840. Archived from the original on December 21, 2017.

- Niall, Keith K. (1988). "On the trichromatic and opponent-process theories: An article by E. Schrödinger". Spatial Vision. 3 (2): 79–95. doi:10.1163/156856888x00050. PMID 3153667.

- Hurvich LM, Jameson D (November 1957). "An opponent-process theory of color vision". Psychological Review. 64, Part 1 (6): 384–404. doi:10.1037/h0041403. PMID 13505974. S2CID 27613265.

- Wolfe JM, Kluender KR, Levi DM (2009). Sensation & Perception (third ed.). New York: Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60535-875-8.

- Svaetichin G, Macnichol EF (November 1959). "Retinal mechanisms for chromatic and achromatic vision". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 74 (2): 385–404. Bibcode:1959NYASA..74..385S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1958.tb39560.x. PMID 13627867. S2CID 27130943.

- De Valois RL, Smith CJ, Kitai ST, Karoly AJ (January 1958). "Response of single cells in monkey lateral geniculate nucleus to monochromatic light". Science. 127 (3292): 238–9. Bibcode:1958Sci...127..238D. doi:10.1126/science.127.3292.238. PMID 13495504.

- Wiesel TN, Hubel DH (November 1966). "Spatial and chromatic interactions in the lateral geniculate body of the rhesus monkey". Journal of Neurophysiology. 29 (6): 1115–56. doi:10.1152/jn.1966.29.6.1115. PMID 4961644.

- Wagner HG, Macnichol EF, Wolbarsht ML (April 1960). "Opponent Color Responses in Retinal Ganglion Cells". Science. 131 (3409): 1314. Bibcode:1960Sci...131.1314W. doi:10.1126/science.131.3409.1314. PMID 17784397. S2CID 46122073.

- Naka KI, Rushton WA (August 1966). "S-potentials from colour units in the retina of fish (Cyprinidae)". The Journal of Physiology. 185 (3): 536–55. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp008001. PMC 1395833. PMID 5918058.

- Daw NW (November 1967). "Goldfish retina: organization for simultaneous color contrast". Science. 158 (3803): 942–4. Bibcode:1967Sci...158..942D. doi:10.1126/science.158.3803.942. PMID 6054169. S2CID 1108881.

- Byzov AL, Trifonov JA (July 1968). "The response to electric stimulation of horizontal cells in the carp retina". Vision Research. 8 (7): 817–22. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(68)90132-6. PMID 5664016.

- Gouras P, Zrenner E (January 1981). "Color coding in primate retina". Vision Research. 21 (11): 1591–8. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(81)90039-0. PMID 7336591. S2CID 46225236.

- Derrington AM, Krauskopf J, Lennie P (December 1984). "Chromatic mechanisms in lateral geniculate nucleus of macaque". The Journal of Physiology. 357 (1): 241–65. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015499. PMC 1193257. PMID 6512691.

- Reid RC, Shapley RM (April 1992). "Spatial structure of cone inputs to receptive fields in primate lateral geniculate nucleus". Nature. 356 (6371): 716–8. Bibcode:1992Natur.356..716R. doi:10.1038/356716a0. PMID 1570016. S2CID 22357719.

- Lankheet MJ, Lennie P, Krauskopf J (January 1998). "Distinctive characteristics of subclasses of red–green P-cells in LGN of macaque". Visual Neuroscience. 15 (1): 37–46. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.553.5684. doi:10.1017/s0952523898151027. PMID 9456503. S2CID 1558413.

- Grigg ER (1967). Biologic Relativity. Chicago: Amaranth Books.

- Solomon RL, Corbit JD (April 1973). "An opponent-process theory of motivation. II. Cigarette addiction". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 81 (2): 158–71. doi:10.1037/h0034534. PMID 4697797.

- Solomon RL, Corbit JD (March 1974). "An opponent-process theory of motivation. I. Temporal dynamics of affect". Psychological Review. 81 (2): 119–45. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.468.2548. doi:10.1037/h0036128. PMID 4817611.

- Geusebroek JM, van den Boomgaard R, Smeulders AW, Geerts H (December 2001). "Color invariance". IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 23 (12): 1338–1350. doi:10.1109/34.977559.

- Barghout L (2014). "Visual taxometric approach to image segmentation using fuzzy-spatial taxon cut yields contextually relevant regions". Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems. Springer International Publishing.

- US 2004059754, Barghout L, Lee L, "Perceptual information processing system", published 25 March 2004

- Barghout L (21 February 2014). Vision: Global Perceptual Context Changes Local Contrast Processing, Updated to include computer vision techniques. Scholars' Press.

- Jameson K, D'Andrade RG (1997), "It's not really red, green, yellow, blue: An inquiry into perceptual color space", Color Categories in Thought and Language, Cambridge University Press, pp. 295–319, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511519819.014, ISBN 9780511519819

- De Valois RL, De Valois KK (May 1993). "A multi-stage color model". Vision Research. 33 (8): 1053–65. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(93)90240-w. PMID 8506645. S2CID 53187961.

- Valberg A (September 2001). "Corrigendum to "Unique hues: an old problem for a new generation"". Vision Research. 41 (21): 2811. doi:10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00243-7. ISSN 0042-6989. S2CID 1541112.

- Webster MA, Miyahara E, Malkoc G, Raker VE (September 2000). "Variations in normal color vision. II. Unique hues". Journal of the Optical Society of America A. 17 (9): 1545–55. Bibcode:2000JOSAA..17.1545W. doi:10.1364/josaa.17.001545. PMID 10975364.

- Wuerger SM, Atkinson P, Cropper S (November 2005). "The cone inputs to the unique-hue mechanisms". Vision Research. 45 (25–26): 3210–23. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2005.06.016. PMID 16087209. S2CID 5778387.

- Zeki S, Cheadle S, Pepper J, Mylonas D (2017). "The Constancy of Colored After-Images". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 11: 229. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2017.00229. PMC 5423953. PMID 28539878.

- Pridmore RW (2012-10-16). "Single cell spectrally opposed responses: opponent colours or complementary colours?". Journal of Optics. 42 (1): 8–18. doi:10.1007/s12596-012-0090-0. ISSN 0972-8821. S2CID 122835809.

- Griggs RA (2009). "Sensation and perception". Psychology: A Concise Introduction (2 ed.). Worth Publishers. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-4292-0082-0. OCLC 213815202.

color information is processed at the post-receptor cell level (by bipolar, ganglion, thalamic, and cortical cells) according to the opponent-process theory.

- ^ Conway, Bevil R.; Malik-Moraleda, Saima; Gibson, Edward (June 30, 2023). "Color appearance and the end of Hering's Opponent-Colors Theory". Cell. 27 (9): 791–804. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2023.06.003. PMC 10527909. PMID 37394292.

Further reading

- Baccus SA (2007). "Timing and computation in inner retinal circuitry". Annual Review of Physiology. 69: 271–90. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.120205.124451. PMID 17059359.

- Masland RH (August 2001). "Neuronal diversity in the retina". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 11 (4): 431–6. doi:10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00230-0. PMID 11502388. S2CID 42917038.

- Masland RH (September 2001). "The fundamental plan of the retina". Nature Neuroscience. 4 (9): 877–86. doi:10.1038/nn0901-877. PMID 11528418. S2CID 205429773.

- Sowden PT, Schyns PG (December 2006). "Channel surfing in the visual brain" (PDF). Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 10 (12): 538–45. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.10.007. PMID 17071128. S2CID 6941223. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- Wässle H (October 2004). "Parallel processing in the mammalian retina". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 5 (10): 747–57. doi:10.1038/nrn1497. PMID 15378035. S2CID 10518721.

- Manzotti, R (2017). "A Perception-Based Model of Complementary Afterimages". SAGE Open. 7 (1). doi:10.1177/2158244016682478.

- Yurtoğlu N (2018). "History Studies: International Journal of History" (PDF). 10 (7): 241–264. doi:10.9737/hist.2018.658. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-11-06. Retrieved 2021-05-03.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Brogaard B, Gatzia DE (2016). "Cortical Color and the Cognitive Sciences". Topics in Cognitive Science. 9 (1): 135–150. doi:10.1111/tops.12241. PMID 28000986. Archived from the original on 2022-10-07. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

| Physiology of the visual system | |

|---|---|

| Vision | |

| Color vision | |