| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (February 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Body hair | |

|---|---|

Hair on the arm Hair on the arm | |

Typical distribution of body hair in females and males Typical distribution of body hair in females and males | |

| Anatomical terminology[edit on Wikidata] |

Body hair or androgenic hair is terminal hair that develops on the human body during and after puberty. It is different from head hair and also from less visible vellus hair, which is much finer and lighter in colour. Growth of androgenic hair is related to the level of androgens (male hormones) and the density of androgen receptors in the dermal papillae. Both must reach a threshold for the proliferation of hair follicle cells.

From childhood onward, regardless of sex, vellus hair covers almost the entire area of the human body. Exceptions include the lips, the backs of the ears, palms of hands, soles of the feet, certain external genital areas, the navel, and scar tissue. Density of hair – i.e. the number of hair follicles per unit area of skin – varies from person to person. In many cases, areas on the human body that contain vellus hair will begin to produce darker and thicker body hair during puberty, such as the first growth of beard hair on a male and female adolescent's previously smooth chin; although it may appear thinner on the female.

Androgenic hair follows the same growth pattern as the hair that grows on the scalp, but with a shorter anagen phase and longer telogen phase. While the anagen phase for the hair on one's head lasts for years, the androgenic hair growth phase for body hair lasts a few months. The telogen phase for hair lasts for varying lengths of time, depending on where the hair is, from a few weeks up to nearly a year. This shortened growing period and extended dormant period explains why the hair on the head tends to be much longer than other hair found on the body. Differences in length seen in comparing the hair on the back of the hand and pubic hair, for example, can be explained by varied growth cycles in those regions. The same goes for differences in body hair length seen in different people, especially when comparing men and women.

Distribution

Like much of the hair on the human body, leg, arm, chest, and back hair begin as vellus hair. As people age, the hair in these regions begins to grow darker and more abundantly. This growth occurs during or after puberty. Men will often have more abundant, coarser hair on the arms and back, while women tend to have a less drastic change in the hair growth in these areas but do experience a significant change in thickness of hairs. However, some women will grow darker, longer hair in one or more of these regions.

Chest and abdomen

Vellus hair grows on the chest and abdomen of both sexes at all stages of development. During the final stages of puberty and extending into adulthood, men grow increasing amounts of terminal hair over the chest and abdomen areas. Adult women can also grow terminal hairs around the areola, though in many cultures these hairs are removed.

Arms

Arm hair grows on a human's forearms, sometimes even on the elbow area, and rarely on a human's bicep, triceps, and/or shoulders. Terminal arm hair is concentrated on the wrist end of the forearm, extending over the hand. Terminal hair growth in adolescent males is often much more intense than that in females, particularly for individuals with dark hair. In some cultures, it is common for women to remove arm hair, though this practice is less frequent than that of leg hair removal.

Terminal hair growth on arms is a secondary sexual characteristic in boys and appears in the last stages of puberty. Vellus arm hair is usually concentrated on the elbow end of the forearm and often ends on the lower part of the upper arm. This type of intense arm vellus hair growth sometimes occurs in girls and children of both sexes until puberty. Even though this causes the arms to appear hairy, it is not caused solely by testosterone. The hair is softer and different from terminal arm hair, in texture.

The longest arm hair ever recorded was done so in California by David Reed in 2017. In 2024, Macie Davis-Southerland measured one hair at 7.24 inches long.

Feet

Visible hair appearing on the top surfaces of the feet and toes generally begins with the onset of puberty. Terminal hair growth on the feet is typically more intense in adult and adolescent males than in females.

Legs

Main article: Leg hair

Leg hair sometimes appears at the onset of adulthood, with the legs of men more often hairier than those of women. For a variety of reasons, people may shave their leg hair, including cultural practice or individual needs. Around the world, women generally shave their leg hair more regularly than men, to conform with the social norms of many cultures, many of which perceive smooth skin as a sign of youth, beauty, and in some cultures, hygiene. However, athletes of both sexes – swimmers, runners, cyclists and bodybuilders in particular – may shave their androgenic hair to reduce friction, highlight muscular development or to make it easier to get into and out of skin-tight clothing.

Pubic

Main article: Pubic hairPubic hair is a collection of coarse hair found in the pubic region. It will often also grow on the thighs and abdomen. Zoologist Desmond Morris disputes theories that it developed to signal sexual maturity or protect the skin from chafing during copulation, and prefers the explanation that pubic hair acts as a scent trap. Also, both sexes having thick pubic hairs act as a partial cushion during intercourse.

The genital area of males and females are first inhabited by shorter, lighter vellus hairs that are next to invisible and only begin to develop into darker, thicker pubic hair at puberty. At this time, the pituitary gland secretes gonadotropin hormones which trigger the production of testosterone in the testicles and ovaries, promoting pubic hair growth. The average ages pubic hair begins to grow in males and females are 12 and 11, respectively. However, in some females, pubic hair has been known to start growing as early as age 8.

Just as individual people differ in scalp hair color, they can also differ in pubic hair color. Differences in thickness, growth rate, and length are also evident.

Axillary

Main article: Underarm hairUnderarm hair normally starts to appear at the beginning of puberty, with growth usually completed by the end of the teenage years.

Today in much of the world, it is common for women to regularly shave their underarm hair. The prevalence of this practice varies widely, though. The practice became popular for cosmetic reasons around 1915 in the United States and United Kingdom, when one or more magazines showed a woman in a dress with shaved underarms. Regular shaving became feasible with the introduction of the safety razor at the beginning of the 20th century. While underarm shaving was quickly adopted in some English speaking countries, especially in the US and Canada, it did not become widespread in Europe until well after World War II. Since then the practice has spread worldwide; some men also choose to shave their armpits.

Facial

Main article: Facial hair

Facial hair grows primarily on or around one's face. Both men and women experience facial hair growth. Like pubic hair, non-vellus facial hair will begin to grow in around puberty. Moustaches in young men usually begin to grow in at around the age of puberty, although some men may not grow a moustache until they reach late teens or at all. In some cases facial hair development may take longer to mature than the late teens, and some men experience no facial hair development even at an older age.

It is common for many women to develop a few facial hairs under or around the chin, along the sides of the face (in the area of sideburns), or on the upper lip. These may appear at any age after puberty but are often seen in women after menopause due to decreased levels of estrogen. A darkening of the vellus hair of the upper lip in women is not considered true facial hair, though it is often referred to as a "moustache"; the appearance of these dark vellus hairs may be lessened by bleaching. A relatively small number of women are able to grow enough facial hair to have a distinct beard. In some cases, female beard growth is the result of a hormonal imbalance (usually androgen excess), or a rare genetic disorder known as hypertrichosis. Sometimes it is caused by use of anabolic steroids. Cultural pressure leads most women to remove facial hair, as it may be viewed as a social stigma.

Development

Main article: Human hair growth| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Hair follicles are to varying degrees sensitive to androgens, primarily testosterone and its derivatives, particularly dihydrotestosterone, with different areas on the body having different sensitivity. As androgen levels increase, the rate of hair growth and the weight of the hairs increase. Genetic factors determine both individual levels of androgen and the hair follicle's sensitivity to androgen, as well as other characteristics such as hair colour, type of hair and hair retention.

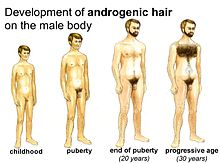

Rising levels of androgens during puberty cause vellus hair to transform into terminal hair over many areas of the body. The sequence of appearance of terminal hair reflects the level of androgen sensitivity, with pubic hair being the first to appear due to the area's special sensitivity to androgen. The appearance of pubic hair in both sexes is usually seen as an indication of the start of a person's puberty. There is a sexual differentiation in the amount and distribution of androgenic hair, with men tending to have more terminal hair in more areas. This includes facial hair, chest hair, abdominal hair, leg hair, arm hair, and foot hair. (See Table 1 for development of male body hair during puberty.) Women retain more of the less visible vellus hair, although leg, arm, and foot hair can be noticeable on women. It is not unusual for women to have a few terminal hairs around their nipples as well. In the later decades of life, especially after the fifth decade, there begins a noticeable reduction in body hair especially in the legs. The reason for this is not known but it could be due to poorer circulation, lower free circulating hormone amounts or other reasons.

Source:

Function

Androgenic hair provides tactile sensory input by transferring hair movement and vibration via the shaft to sensory nerves within the skin. Follicular nerves detect displacement of hair shafts and other nerve endings in the surrounding skin detect vibration and distortions of the skin around the follicles. Androgenic hair extends the sense of touch beyond the surface of the skin into the air and space surrounding it, detecting air movements as well as hair displacement from contact by insects or objects.

Evolution

Determining the evolutionary function of androgenic hair must take into account both human evolution and the thermal properties of hair itself.

The thermodynamic properties of hair are based on the properties of the keratin strands and amino acids that combine into a 'coiled' structure. This structure lends to many of the properties of hair, such as its ability to stretch and return to its original length. This coiled structure does not predispose curly or frizzy hair, both of which are defined by oval or triangular hair follicle cross-sections.

Evolution of less body hair

Hair is a very good thermal conductor and aids heat transfer both into and out of the body. When goose bumps are observed, small muscles (arrector pili muscle) contract to raise the hairs either to provide insulation, by reducing cooling of the skin by air convection, or in response to central nervous stimulus, similar to the feeling of "hairs standing up on the back of your neck". This phenomenon also occurs when static charge is built up and stored in the hair. Keratin however can easily be damaged by excessive heat and dryness, suggesting that extreme sun exposure, perhaps due to a lack of clothing, would result in perpetual hair destruction, eventually resulting in the genes being bred out in favor of high skin pigmentation. It is also true that parasites can live on and in hair thus peoples who preserved their body hair would have required greater general hygiene to prevent diseases.

Markus J. Rantala of the Department of Biological and Environmental Science, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, said humans evolved by "natural selection" to be hairless when the trade off of "having fewer parasites" became more important than having a "warming, furry coat".

P. E. Wheeler of the Department of Biology at Liverpool Polytechnic said quadrupedal savanna mammals of similar volume to humans have body hair to keep warm while only larger quadrupedal savanna mammals lack body hair, because their body volume itself is enough to keep them warm. Therefore Wheeler said that humans, who should have body hair based on predictions of body volume alone for savanna mammals, evolved no body hair after evolving bipedalism, which he said reduced the amount of body area exposed to the sun by 40%, reducing the solar warming effect on the human body.

Loss of fur occurred at least two million years ago, but possibly as early as 3.3 million years ago judging from the divergence of head and pubic lice, and aided persistence hunting (the ability to catch prey in very long distance chases) in the warm savannas where hominins first evolved. The two main advantages are felt to be bipedal locomotion and greater thermal load dissipation capacity due to better sweating and less hair.

Sexual selection

Main article: Sexual selectionMarkus J. Rantala of the Department of Biological and Environmental Science, University of Jyväskylä, Finland, said the existence of androgen dependent hair on men could be explained by sexual attraction whereby hair on the genitals would trap pheromones and hair on the chin would make the chin appear more massive.

Across populations

In 1876, Oscar Peschel wrote that North Asiatic Mongols, Native Americans, Malays, Hottentots and Bushmen have little to no body hair, while Semitic peoples, Indo-Europeans, and Southern Europeans (especially the Portuguese and Spanish) have extensive body hair.

Anthropologist Joseph Deniker said in 1901 that the very hirsute peoples are the Ainus, Uyghurs, Iranians, Australian aborigines (Arnhem Land being less hairy), Toda, Dravidians and Melanesians, while the most glabrous peoples are the Indigenous Americans, San, and East Asians, who include Chinese, Koreans, Mongols, and Malays. Deniker said that hirsute peoples tend to have thicker beards, eyelashes, and eyebrows but fewer hairs on their scalp.

C.H. Danforth and Mildred Trotter of the Department of Anatomy at Washington University in St. Louis conducted a study using American army soldiers of European origin in 1922 where they concluded that dark-haired white men are generally more hairy than fair-haired white men.

H. Harris, publishing in the British Journal of Dermatology in 1947, wrote Native Americans have the least body hair, Han Chinese people and black people have little body hair, white people have more body hair than black people and Ainu have the most body hair.

Anthropologist Arnold Henry Savage Landor described the Ainu as having hairy bodies.

Stewart W. Hindley and Albert Damon of the Department of Anthropology at Stanford University studied, in 1973, the frequency of hair on the middle finger joint (mid-phalangeal hair) of Solomon Islanders, as a part of a series of anthropometric studies of these populations. They summarize other studies on prevalence of this trait as reporting, in general, that Caucasoids are more likely to have hair on the middle finger joint than Negroids, Australoids and Mongoloids, and collect the following frequencies from previously published literature: Andamanese 0%, Inuit 1%, African American 16% or 28%, Ethiopians 25.6%, Mexicans of the Yucatan 20.9%, Penobscot and Shinnecock 22.7%, Gurkha 33.6%, Japanese 44.6%, various Hindus 40–50%, Egyptians 52.3%, Near Eastern peoples 62–71%, various Europeans 60–80%. However, they never completed an Androgenic hair map.

According to anthropologist and professor Ashley Montagu in 1989, many East Asian people and African populations such as the San people are less hairy than Europeans and West Asian peoples. Montagu said that the hairless feature is a neotenous trait.

Eike-Meinrad Winkler and Kerrin Christiansen of the Institut für Humanbiologie studied, in 1993, the Kavango people and !Kung people from Namibia of body hair and hormone levels to investigate the reason some Africans did not have bodies as hairy as Europeans. Winkler and Christiansen concluded the difference in hairiness between some Africans and Europeans had to do with differences in androgen or estradiol production, in androgen metabolism, and in sex hormone action in the target cells.

Valerie Anne Randall of the Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Bradford, said in 1994 beard growth in Caucasian men increases until the mid-thirties due to a delay caused by growth cycles changing from vellus hair to terminal hair. Randall said white men and women are hairier than Japanese men and women even with the same total plasma androgen levels. Randall says that the reason for some people being hairy and some people not being hairy is unclear, but that it probably is related to differing sensitivity of hair follicles to 5α-reductase.

Rodney P. R. Dawber of the Oxford Hair Foundation said in 1997 that East Asian males have little or no facial or body hair and Dawber also said that Mediterranean males are covered with an exuberant pelage.

Milkica Nešić and her colleagues from the Department of Physiology at the University of Niš, Serbia, cited prior studies in a 2010 publication indicating that the frequency of hair on the middle finger joint (mid-phalangeal hair) in Europeans is significantly higher than in African populations, where the lowest values were found, and "completely absent" in Northern Native American (Inuit) populations. Their own study found that the latter was part of a wider trend of "Mongoloid" peoples having less hair overall.

Androgenic hair as biometric

It has been shown that individuals can be uniquely identified by their androgenic hair patterns. For example, even when one's particular distinguishing features such as face and tattoos are obscured, persons can still be identified by their hair on other parts of their body.

See also

References

- Hoover, Ezra; Alhajj, Mandy; Flores, Jose L. (2024), "Physiology, Hair", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29763123, retrieved 8 March 2024

- "California woman proudly grows out the longest arm hair ever". Guinness World Records.

- Morris, Desmond (1985). Bodywatching: a field guide to the human species. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 209.

- Hope, Christine (1982). "Caucasian Female Body Hair and American Culture". Journal of American Culture. 5 (1): 93–99. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1982.0501_93.x.

- Adams, Cecil (6 February 1991). "Who decided women should shave their legs and underarms?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Congenital Hypertrichosis Lanuginosa at eMedicine

- Reynolds EL (March 1951). "The appearance of adult patterns of body hair in man". Ann NY Acad Sci. 53 (3): 576–584. Bibcode:1951NYASA..53..576R. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1951.tb31959.x. PMID 14819884. S2CID 42483235.

- Sabah, N H (February 1974). "Controlled stimulation of hair follicle receptors". Journal of Applied Physiology. 36 (2): 256–257. doi:10.1152/jappl.1974.36.2.256. PMID 4811387.

- "Neuroscience for Kids – Receptors". Faculty.washington.edu. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- "Hair Shape". Hair-science.com. 1 February 2005. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- "Properties Of Hair". Hair-science.com. 1 February 2005. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- ^ Rantala, M.J. (1999). Human nakedness: adaptation against ectoparasites? International Journal for Parasitology 29 1987±1989

- ^ Wheeler, P.E. (1985). "The Loss of Functional Body Hair in Man: the Influence of Thermal Environment, Body Form and Bipedality". Journal of Human Evolution. 14: 23–28. doi:10.1016/s0047-2484(85)80091-9.

- Kittler R, Kayser M, Stoneking M: "Molecular evolution of Pediculus humanus and the origin of clothing". Curr Biol. 2003, 13: 1414–1417. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00507-4. Erratum: Curr Biol 2004, 14:2309.

- Peschel, O. (1876). The Races of Man and Their Geographical Distribution. London: Henry S. King & Co. pp. 96, 97 & 403. Retrieved 21 January 2017, from link.

- ^ Deniker, Joseph (1901). "Chapter I. Somatic Characteristics". The Races of Man: An Outline of Anthropology and Ethnography. London: The Walter Scott Pub. Co. Archived from the original on 20 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Danforth, C. H.; Trotter, Mildred (July 1922). "The distribution of body hair in white subjects". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 5 (3): 259–265. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330050318.

- Harris, H (1947). "The Relation of Hair-Growth on the Body to Baldness". British Journal of Dermatology. 59 (8–9): 300–309. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1947.tb10910.x. PMID 20262897. S2CID 9479118.

- Landor, A. H. S. (2012). Alone with the Hairy Ainu. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139226813. ISBN 978-1-108-04941-2.

- Hindley, S. W.; Damon, A. (1973). "Some genetic traits in Solomon Island populations IV. Mid-phalangeal hair". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 39 (2): 191–194. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330390208. PMID 4750670.

- Montagu, Ashley. Growing Young. Published by Greenwood Publishing Group, 1989 ISBN 0-89789-167-8

- ^ Winkler, E.-M.; Christiansen, K. (1993). "Sex hormone levels and body hair growth in !Kung San and Kavango men from Namibia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 92 (2): 155–164. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330920205. PMID 8273828.

- ^ Randall, V. A. (1994). "Androgens and human hair growth". Clinical Endocrinology. 40 (4): 439–457. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1994.tb02483.x. PMID 8187311. S2CID 12391727.

- Dawber R.P.R. (1997). Diseases of the Head and Scalp (3rd ed.). Virginia: Blackwell Science Ltd.

- Nešić, M. et al. (2010). "Middle phalangeal hair distribution in Serbian high school students". Arch. Biol. Sci., Belgrade, 62 (3), 841–850, doi:10.2298/ABS1003841N.

- Su, Han; Kong, Adams Wai Kin (April 2014). "A Study on Low Resolution Androgenic Hair Patterns for Criminal and Victim Identification". IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security. 9 (4): 666–680. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2014.2306591. S2CID 14132375.

- Huynh, Nhat Quang; Xu, Xingpeng; Kong, Adams Wai Kin; Subbiah, Sathyan (2014). "A preliminary report on a full-body imaging system for effectively collecting and processing biometric traits of prisoners". 2014 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Biometrics and Identity Management (CIBIM). pp. 167–174. doi:10.1109/CIBIM.2014.7015459. ISBN 978-1-4799-4533-7. S2CID 806491.

External links

- [REDACTED] Media related to Body hair at Wikimedia Commons