The prehistoric rock engravings of the Fontainebleau Forest are an abundant collection of rock art discovered among the sandstone boulders of the Fontainebleau Forest. Several thousand petroglyphs have been discovered in the forest, with earliest dating to the Paleolithic (very few examples), roughly 2000 to the early Mesolithic and almost 300 to the late Bronze Age.

The cave engravings can be divided into two broad groups. The most readily visible to the casual observer are largely non-figurative collections of repetitive geometric patterns, usually found in larger rock shelters, some of which were inhabited by Mesolithic peoples. The second, much smaller, group is a series of several hundred figurative engravings that were only recently discovered (2014) in a much more circumscribed area of the Fontainebleau Forest. Many of these engravings are found in small cavities in the sandstone boulders and are not readily visible to passersby.

Non-figurative engravings of the early Mesolithic

The non-figurative engravings of the early Mesolithic were executed during a time of intense rock engraving activity by what would turn out to be the last hunter gatherers of the Fontainebleau region. Thus, these etchings were executed thousands of years later than the Paleolithic cave paintings found in, for example, Lascaux.

Broadly speaking, the Mesolithic engravings take the form of panels of straight grooves which are often organized into grids. In fewer cases, these grooves were presented as isolated lines or formed into crosses. Even more rarely, rudimentary circles or stars were etched. According to an inventory conducted in the 1960s, most of these engravings were small (over 50 percent were 10 cm or less), while 11 percent were relatively large (21 cm or more). Furthermore, the engravings appear to have been executed as an accumulation of art works over time in cavities “with no explicit order, especially on certain abundantly engraved sites”.

The engravings have been known since the nineteenth century and were mainly discovered by casual observers. They are found in cavities that are generally large enough for one or two people to stand in simultaneously. However, some were large enough to be inhabited; in a sample of 49 engraving sites, 13 (or 26 percent) were judged to be inhabitable. A formal inventory conducted by volunteer archeologists documented the presence of such rock etchings in more than 2000 cavities of boulders in the Fontainebleau Forest.

Material found in the caves and thought to be contemporaneous with the etchings provides fairly reliable dating to the Mesolithic. It also appears to indicate that the engravings were part of a day-to-day activity of early Mesolithic society in the forest. The dating of these engravings relies on rigorous archeological excavation of the surrounding sites and analysis of the associated artefacts (tools, etc.) found there. Reliable dating has been facilitated by the fact that a large portion of the ceiling of an inhabited rock shelter collapsed onto Mesolithic vestiges, thereby capturing the Mesolithic traces underneath.

The etchings could only be executed in an outer, thin layer of soft sandstone that has an average thickness of 3 mm and a maximum thickness of 30 mm. This soft sandstone would be washed away by the elements except in protected areas of sandstone boulders. It is presumably for this reason that all the Mesolithic engravings of the Fontainebleau Forest are found in sheltered situations.

The act of engraving on such a surface was reasonably simple and could be accomplished with readily available tools. A reenactment of the creation of such a work using stone tools of the type produced by the works’ creators shows that a single line etching with a length of 15 cm and a depth of 2 mm can be completed in less than 60 seconds and that the engraved grids of the type commonly found in the Fontainebleau Forest can be executed in between 5 and 15 minutes. Specialized engraving expertise was not required. Thus, the engravings “were technically simple to make with easy-to-access tools and therefore could have been carried out by a large number of people, during rather short periods of time.”

Hidden engravings of the late Bronze Age

A less abundant group of largely figurative rock engravings was discovered by archeologists in 2014 in a smaller area (about 30 square kilometers) within, roughly, the southeast quadrant of the Fontainebleau Forest. The original discovery in 2014 led, the following year, to a systematic search of cavities that might also contain such petroglyphs. After 8 years of search, almost 300 panels of petroglyphs were inventoried.

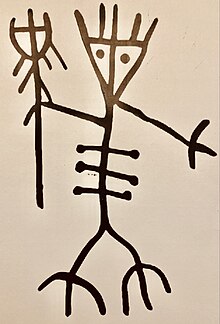

The style of these engravings has been categorized into 2 schools. The first is the ‘Malmontagne’ school, consisting of roughly 200 panels with highly complex panels of human, semi-human and animal figures. Etched with shallow grooves, these elaborate panels are small (often not exceeding 10 centimeters) and depict a rich set of images that are repeated across different sites. These include human and semi-human figures as well as animals (birds, snakes, deer, oxen) and human-made objects (sleds, scepters, rattles and head dresses). In contrast, the ‘Long Rocher’ school, with 80 panels, presents panels of mainly geometric engravings that resemble the Mesolithic petroglyphs described above. Also etched with shallow grooves and located in small cavities, these engravings are rarely figurative and the size of the panels is somewhat larger on average than those of the Malmontagne school. Both schools of petroglyphs are thought to date to the late Bronze Age.

Perhaps the most intriguing characteristic of these panels is that many were executed in small cavities in the boulders, making them extremely hard to see. In some cases, there was only enough room for the artist's arm to enter the cavity, meaning that he was in an extremely uncomfortable working position and that even he could not see well what he was working on. It is perhaps because of this very non-ostentatious style that these petroglyphs only came to the attention of the archeological community in 2014. Furthermore, the apparently deliberate attempt to ‘hide’ the petroglyphs shows a desire for discretion, even secrecy, on the part of their creators and raises questions about the role they played in this Bronze Age culture.

In addition to panels of engravings on boulders, the petroglyphs were also executed on portable blocks of stone and on round, fixed stones used to create three-dimensional engravings, sometimes of what appears to be female creatures. The portable, engraved blocks were found deliberately buried together in groups.

In addition to the information provided by archeological excavations, the dating of these petroglyphs to the late Bronze Age relies on triangulation from a number of established archeological facts. First, the technique used to produce the engraving tools is clearly post-Mesolithic and is also not associated with the early Bronze Age. Second, the presence of images of sleds being pulled by oxen shows that the Malmontagne peoples domesticated animals, meaning the etchings could not have been created earlier than the late Neolithic. Third, the images etched onto late Bronze Age ceramics show a clear link with those of the petroglyphs. Fourth, a bronze version of the rattles depicted in the Malmontagne panels has been found in Germany and reliably dated to the late Bronze Age.

References

- ^ "The forest of Fontainebleau is home to rock art treasures". CNRS News. Retrieved 2023-09-22.

- ^ Tassé, Gilles (1982). "Pétroglyphes du Bassin parisien". Gallia Préhistoire. 16 (1): 42, 60–61.

- ^ Cantin, Alexandre (December 2021). "Graver les grès de Fontainebleau à l'age du Bronze final: perspectives d'experimentations à partir d'un nouveau corpus de l'ensemble rupestre sud francilien". Google Docs (This article was presented to an academic conference held in Paris at the Institute d’art et d’archéologie on June 4, 2021. The title of the conference is: Expérimentons la protohistoire - Dialogues interdisciplinaires.). Retrieved 2023-09-22.

- ^ Guéret, Colas; Bénard, Alain (2017-06-01). ""Fontainebleau rock art" (Ile-de-France, France), an exceptional rock art group dated to the Mesolithic? Critical return on the lithic material discovered in three decorated rock shelters". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 13: 99–120. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.03.039. ISSN 2352-409X.

- ^ Cantin, Alexandre; Valentin, Boris; Thiry, Médard; Guéret, Colas (2022-10-01). "Social context of Mesolithic rock engravings in the Fontainebleau sandstone region (Paris Basin, France): Contribution of the experimental study". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 45: 103554. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103554. ISSN 2352-409X.

- Bénard, Alain; Guéret, Colas (2014-02-10). "The Decorated Mesolithic Rock Shelters South of Île-de-France: Revision of the Archaeological Data and Research Perspectives". Palethnologie. Archéologie et sciences humaines (6). doi:10.4000/palethnologie.1678. ISSN 2108-6532.

- ^ Cantin, Alexandre (December 2021). "Graver les grès de Fontainebleau à l'age du Bronze final: perspectives d'experimentations à partir d'un nouveau corpus de l'ensemble rupestre sud francilien". Google Docs (This article was presented to an academic conference held in Paris at the Institute d’art et d’archéologie on June 4, 2021. The title of the conference is: Expérimentons la protohistoire - Dialogues interdisciplinaires.). Retrieved 2023-09-22.

- ^ Simonin, Daniel; Valois, Laurent (2023). Pierres secrètes: Mythologie pré celtique en foret de Fontainebleau. Errance & Picard and Musée de Préhistoire d'Ile-de-France. ISBN 9782330176969.

- ^ Simonin, Daniel; Valois, Laurent (2023). Pierres secrètes: Mythologie pré celtique en foret de Fontainebleau. Errance & Picard and Musée de Préhistoire d'Ile-de-France. ISBN 9782330176969.