| Punjabi | |

|---|---|

| |

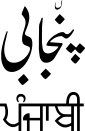

'Punjabi' written in Shahmukhi script (top) and Gurmukhi script (bottom) 'Punjabi' written in Shahmukhi script (top) and Gurmukhi script (bottom) | |

| Pronunciation | [pəɲˈdʒab̆.bi] |

| Native to | India Pakistan |

| Region | Punjab |

| Ethnicity | Punjabis |

| Native speakers | 150 million (2011–2023) |

| Language family | Indo-European |

| Early forms | Prakrit (debated) |

| Standard forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| Writing system |

|

| Official status | |

| Official language in |

|

| Regulated by | List |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | pa |

| ISO 639-2 | pan |

| ISO 639-3 | pan |

| Glottolog | lahn1241 |

| Linguasphere | 59-AAF-e |

Geographic distribution of Punjabi language in Pakistan and India. Geographic distribution of Punjabi language in Pakistan and India. | |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. | |

| Part of a series on |

| Punjabis |

|---|

|

| History |

|

DiasporaAsia

Europe North America Oceania |

| Culture |

| Regions |

Punjab portal |

Punjabi, sometimes spelled Panjabi, is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Punjab region of Pakistan and India. It is one of the most widely spoken native languages in the world with approximately 150 million native speakers.

Punjabi is the most widely-spoken first language in Pakistan, with 88.9 million native speakers according to the 2023 Pakistani census, and the 11th most widely-spoken in India, with 31.1 million native speakers, according to the 2011 census. It is spoken among a significant overseas diaspora, particularly in Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, and the Gulf states.

In Pakistan, Punjabi is written using the Shahmukhi alphabet, based on the Perso-Arabic script; in India, it is written using the Gurmukhi alphabet, based on the Indic scripts. Punjabi is unusual among the Indo-Aryan languages and the broader Indo-European language family in its usage of lexical tone.

History

Etymology

The word Punjabi (sometimes spelled Panjabi) has been derived from the word Panj-āb, Persian for 'Five Waters', referring to the five major eastern tributaries of the Indus River. The name of the region was introduced by the Turko-Persian conquerors of South Asia and was a translation of the Sanskrit name, Panchanada, which means 'Land of the Five Rivers'.

Panj is cognate with Sanskrit pañca (पञ्च), Greek pénte (πέντε), and Lithuanian Penki, all of which meaning 'five'; āb is cognate with Sanskrit áp (अप्) and with the Av- of Avon. The historical Punjab region, now divided between India and Pakistan, is defined physiographically by the Indus River and these five tributaries. One of the five, the Beas River, is a tributary of another, the Sutlej.

Origin

Punjabi developed from Prakrit languages and later Apabhraṃśa (Sanskrit: अपभ्रंश, 'deviated' or 'non-grammatical speech') From 600 BC, Sanskrit developed as the standard literary and administrative language and Prakrit languages evolved into many regional languages in different parts of India. All these languages are called Prakrit languages (Sanskrit: प्राकृत, prākṛta) collectively. Paishachi Prakrit was one of these Prakrit languages, which was spoken in north and north-western India and Punjabi developed from this Prakrit. Later in northern India Paishachi Prakrit gave rise to Paishachi Apabhraṃśa, a descendant of Prakrit. Punjabi emerged as an Apabhramsha, a degenerated form of Prakrit, in the 7th century AD and became stable by the 10th century. The earliest writings in Punjabi belong to the Nath Yogi-era from 9th to 14th century. The language of these compositions is morphologically closer to Shauraseni Apbhramsa, though vocabulary and rhythm is surcharged with extreme colloquialism and folklore. Writing in 1317–1318, Amir Khusrau referred to the language spoken by locals around the area of Lahore as Lahauri. The precursor stage of Punjabi between the 10th and 16th centuries is termed 'Old Punjabi', whilst the stage between the 16th and 19th centuries is termed as 'Medieval Punjabi'.

Arabic and Persian influences

See also: Persian language in the Indian subcontinentThe Arabic and Modern Persian influence in the historical Punjab region began with the late first millennium Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent. Since then, many Persian words have been incorporated into Punjabi (such as zamīn, śahir etc.) and are used with a liberal approach. Through Persian, Punjabi also absorbed many Arabic-derived words like dukān, ġazal and more, as well as Turkic words like qēncī, sōġāt, etc. After the fall of the Sikh empire, Urdu was made the official language of Punjab under the British (in Pakistani Punjab, it is still the primary official language) and influenced the language as well.

In the second millennium, Punjabi was lexically influenced by Portuguese (words like almārī), Greek (words like dām), Japanese (words like rikśā), Chinese (words like cāh, līcī, lukāṭh) and English (words like jajj, apīl, māsṭar), though these influences have been minor in comparison to Persian and Arabic. In fact, the sounds /z/ (ਜ਼ / ز ژ ذ ض ظ), /ɣ/ (ਗ਼ / غ), /q/ (ਕ਼ / ق), /ʃ/ (ਸ਼ / ش), /x/ (ਖ਼ / خ) and /f/ (ਫ਼ / ف) are all borrowed from Persian, but in some instances the latter three arise natively. Later, the letters ਜ਼ / ز, ਸ਼ / ش and ਫ਼ / ف began being used in English borrowings, with ਸ਼ / ش also used in Sanskrit borrowings.

Punjabi has also had minor influence from and on neighbouring languages such as Sindhi, Haryanvi, Pashto and Hindustani.

| English | Gurmukhi-based (Punjab, India) | Shahmukhi-based (Punjab, Pakistan) |

|---|---|---|

| President | ਰਾਸ਼ਟਰਪਤੀ (rāshtarpatī) | صدرمملکت (sadar-e mumlikat) |

| Article | ਲੇਖ (lēkh) | مضمون (mazmūn) |

| Prime Minister | ਪਰਧਾਨ ਮੰਤਰੀ (pardhān mantarī)* | وزیراعظم (vazīr-e aʿzam) |

| Family | ਪਰਵਾਰ (parvār)* ਟੱਬਰ (ṭabbar) |

خاندان (kḥāndān) ٹبّر (ṭabbar) |

| Philosophy | ਫ਼ਲਸਫ਼ਾ (falsafā) ਦਰਸ਼ਨ (darshan) |

فلسفہ (falsafah) |

| Capital city | ਰਾਜਧਾਨੀ (rājdhānī) | دارالحکومت (dār-al ḥakūmat) |

| Viewer | ਦਰਸ਼ਕ (darshak) | ناظرین (nāzarīn) |

| Listener | ਸਰੋਤਾ (sarotā) | سامع (sāmaʿ) |

Note: In more formal contexts, hypercorrect Sanskritized versions of these words (ਪ੍ਰਧਾਨ pradhān for ਪਰਧਾਨ pardhān and ਪਰਿਵਾਰ parivār for ਪਰਵਾਰ parvār) may be used.

Modern times

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Punjabi language" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Modern Punjabi emerged in the 19th century from the Medieval Punjabi stage. Modern Punjabi has two main varieties, Western Punjabi and Eastern Punjabi, which have many dialects and forms, altogether spoken by over 150 million people. The Majhi dialect, which is transitional between the two main varieties, has been adopted as standard Punjabi in India and Pakistan for education and mass media. The Majhi dialect originated in the Majha region of the Punjab.

In India, Punjabi is written in the Gurmukhī script in offices, schools, and media. Gurmukhi is the official standard script for Punjabi, though it is often unofficially written in the Latin scripts due to influence from English, one of India's two primary official languages at the Union-level.

In Pakistan, Punjabi is generally written using the Shahmukhī script, which in literary standards, is identical to the Urdu alphabet, however various attempts have been made to create certain, distinct characters from a modification of the Persian Nastaʿlīq characters to represent Punjabi phonology, not already found in the Urdu alphabet. In Pakistan, Punjabi loans technical words from Persian and Arabic, just like Urdu does.

Geographic distribution

Punjabi is the most widely spoken language in Pakistan, the eleventh-most widely spoken in India, and also present in the Punjabi diaspora in various countries.

Approximate distribution of native Punjabi speakers (inc. Lahndic dialects) (assuming a rounded total of 157 million) worldwide.

Pakistan (inc. all Pakistani provinces) (78.6%) India (inc. all Indian states) (19.8%) Other Countries (1.6%)Pakistan

Punjabi is the most widely spoken language in Pakistan, being the native language of 88.9 million people, or approximately 37% of the country's population.

| Year | Population of Pakistan | Percentage | Punjabi speakers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 33,740,167 | 57.08% | 22,632,905 |

| 1961 | 42,880,378 | 56.39% | 28,468,282 |

| 1972 | 65,309,340 | 56.11% | 43,176,004 |

| 1981 | 84,253,644 | 48.17% | 40,584,980 |

| 1998 | 132,352,279 | 44.15% | 58,433,431 |

| 2017 | 207,685,000 | 38.78% | 80,540,000 |

| 2023 | 240,458,089 | 36.98% | 88,915,544 |

Beginning with the 1981 and 2017 censuses respectively, speakers of the Western Punjabi's Saraiki and Hindko varieties were no longer included in the total numbers for Punjabi, which explains the apparent decrease. Pothwari speakers however are included in the total numbers for Punjabi.

India

See also: States of India by Punjabi speakers

Punjabi is the official language of the Indian state of Punjab, and has the status of an additional official language in Haryana and Delhi. Some of its major urban centres in northern India are Amritsar, Ludhiana, Chandigarh, Jalandhar, Ambala, Patiala, Bathinda, Hoshiarpur, Firozpur and Delhi.

In the 2011 census of India, 31.14 million reported their language as Punjabi. The census publications group this with speakers of related "mother tongues" like Bagri and Bhateali to arrive at the figure of 33.12 million.

| Year | Population of India | Punjabi speakers in India | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 548,159,652 | 14,108,443 | 2.57% |

| 1981 | 665,287,849 | 19,611,199 | 2.95% |

| 1991 | 838,583,988 | 23,378,744 | 2.79% |

| 2001 | 1,028,610,328 | 29,102,477 | 2.83% |

| 2011 | 1,210,193,422 | 33,124,726 | 2.74% |

Punjabi diaspora

See also: Punjabi diasporaPunjabi is also spoken as a minority language in several other countries where Punjabi people have emigrated in large numbers, such as the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada.

There were 670,000 native Punjabi speakers in Canada in 2021, 300,000 in the United Kingdom in 2011, 280,000 in the United States and smaller numbers in other countries.

Punjabi speakers by country

| Country | Native number of speakers | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 88,915,544 | Census | |

| 33,124,726 | Census | |

| 800,000 | Ethnologue | |

| 670,000 | Census | |

| 291,000 | Census | |

| 280,867 | Census | |

| 239,033 | Census | |

| 201,000 | Ethnologue |

Major dialects

Main article: Punjabi dialects and languagesStandard Punjabi

Standard Punjabi (sometimes referred to as Majhi) is the standard form of Punjabi used commonly in education and news broadcasting, and is based on the Majhi dialect. Such as the variety used on Google Translate, Standard Punjabi is also often used in official online services that employ Punjabi. It is widely used in the TV and entertainment industry of Pakistan, which is mainly produced in Lahore.

The Standard Punjabi used in India and Pakistan have slight differences. In India, it discludes many of the dialect-specific features of Majhi. In Pakistan, the standard is closer to the Majhi spoken in the urban parts of Lahore.

Eastern Punjabi

"Eastern Punjabi" refers to the varieties of Punjabi spoken in Pakistani Punjab (specifically Northern Punjabi), most of Indian Punjab, the far-north of Rajasthan and on the northwestern border of Haryana. It includes the dialects of Majhi, Malwai, Doabi, Puadhi and the extinct Lubanki.

Sometimes, Dogri and Kangri are grouped into this category.

Western Punjabi

Main article: Lahnda"Western Punjabi" or "Lahnda" (لہندا, lit. 'western') is the name given to the diverse group of Punjabi varieties spoken in the majority of Pakistani Punjab, the Hazara region, most of Azad Kashmir and small parts of Indian Punjab such as Fazilka. These include groups of dialects like Saraiki, Pahari-Pothwari, Hindko and the extinct Inku; common dialects like Jhangvi, Shahpuri, Dhanni and Thali which are usually grouped under the term Jatki Punjabi; and the mixed variety of Punjabi and Sindhi called Khetrani.

Depending on context, the terms Eastern and Western Punjabi can simply refer to all the Punjabi varieties spoken in India and Pakistan respectively, whether or not they are linguistically Eastern/Western.

Phonology

While a vowel length distinction between short and long vowels exists, reflected in modern Gurmukhi orthographical conventions, it is secondary to the vowel quality contrast between centralised vowels /ɪ ə ʊ/ and peripheral vowels /iː eː ɛː aː ɔː oː uː/ in terms of phonetic significance.

| Front | Near-front | Central | Near-back | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | iː ਈ اِی | uː ਊ اُو | |||

| Near-close | ɪ ਇ اِ | ʊ ਉ اُ | |||

| Close-mid | eː ਏ اے | oː ਓ او | |||

| Mid | ə ਅ اَ | ||||

| Open-mid | ɛː ਐ اَے | ɔː ਔ اَو | |||

| Open | aː ਆ آ |

The peripheral vowels have nasal analogues. There is a tendency with speakers to insert /ɪ̯/ between adjacent "a"-vowels as a separator. This usually changes to /ʊ̯/ if either vowel is nasalised.

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Post-alv./ Palatal |

Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ਮ م | n ਨ ن | ɳ ਣ ݨ | (ɲ) ਞ ن٘ | (ŋ) ਙ ن٘ | |||

| Stop/ Affricate |

tenuis | p ਪ پ | t̪ ਤ ت | ʈ ਟ ٹ | t͡ʃ ਚ چ | k ਕ ک | (q ਕ਼ ق) | |

| aspirated | pʰ ਫ پھ | tʰ ਥ تھ | ʈʰ ਠ ٹھ | t͡ʃʰ ਛ چھ | kʰ ਖ کھ | |||

| voiced | b ਬ ب | d̪ ਦ د | ɖ ਡ ڈ | d͡ʒ ਜ ج | ɡ ਗ گ | |||

| tonal | ਭ بھ | ਧ دھ | ਢ ڈھ | ਝ جھ | ਘ گھ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | (f ਫ਼ ف) | s ਸ س | ʃ ਸ਼ ش | (x ਖ਼ خ) | |||

| voiced | (z ਜ਼ ز) | (ɣ ਗ਼ غ) | ɦ ਹ ہ | |||||

| Rhotic | ɾ~r ਰ ر | ɽ ੜ ڑ | ||||||

| Approximant | ʋ ਵ و | l ਲ ل | ɭ ਲ਼ ࣇ | j ਯ ی | ||||

Note: for the tonal stops, refer to the next section about Tone.

The three retroflex consonants /ɳ, ɽ, ɭ/ do not occur initially, and the nasals most commonly occur as allophones of /n/ in clusters with velars and palatals (there are few exceptions). The well-established phoneme /ʃ/ may be realised allophonically as the voiceless retroflex fricative in learned clusters with retroflexes. Due to its foreign origin, it is often also realised as , in e.g. shalwār /salᵊ.ʋaːɾᵊ/. The phonemic status of the consonants /f, z, x, ɣ, q/ varies with familiarity with Hindustani norms, more so with the Gurmukhi script, with the pairs /f, pʰ/, /z, d͡ʒ/, /x, kʰ/, /ɣ, g/, and /q, k/ systematically distinguished in educated speech, /q/ being the most rarely pronounced. The retroflex lateral is most commonly analysed as an approximant as opposed to a flap. Some speakers soften the voiceless aspirates /t͡ʃʰ, pʰ, kʰ/ into fricatives /ɕ, f, x/ respectively.

In rare cases, the /ɲ/ and /ŋ/ phonemes in Shahmukhi may be represented with letters from Sindhi. The /ɲ/ phoneme, which is more common than /ŋ/, is written as نی or نج depending on its phonetic preservation, e.g. نیاݨا /ɲaːɳaː/ (preserved ñ) as opposed to کنج /kiɲd͡ʒ/ (assimilated into nj). /ŋ/ is always written as نگ.

Diphthongs

Like Hindustani, the diphthongs /əɪ/ and /əʊ/ have mostly disappeared, but are still retained in some dialects.

Phonotactically, long vowels /aː, iː, uː/ are treated as doubles of their short vowel counterparts /ə, ɪ, ʊ/ rather than separate phonemes. Hence, diphthongs like ai and au get monophthongised into /eː/ and /oː/, and āi and āu into /ɛː/ and /ɔː/ respectively.

The phoneme /j/ is very fluid in Punjabi. /j/ is only truly pronounced word-initially (even then it often becomes /d͡ʒ/), where it is otherwise /ɪ/ or /i/.

Tone

Unusually for an Indo-Aryan language, Punjabi distinguishes lexical tones. Three tones are distinguished in Punjabi (some sources have described these as tone contours, given in parentheses): low (high-falling), high (low-rising), and level (neutral or middle). The transcriptions and tone annotations in the examples below are based on those provided in Punjabi University, Patiala's Punjabi-English Dictionary.

| Examples | Pronunciation | Meaning | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gurmukhi | Shahmukhi | Transliteration | IPA | Tone | |

| ਘਰ | گھر | ghar | /kə̀.rᵊ/ | low | house |

| ਕਰ੍ਹਾ | کرھا | karhā | /kə́.ra/ | high | powdered remains of cow-dung cakes |

| ਕਰ | کر | kar | /kər/ | level | do, doing |

| ਝੜ | جھڑ | jhaṛ | /t͡ʃə̀.ɽᵊ/ | low | shade caused by clouds |

| ਚੜ੍ਹ | چڑھ | chaṛh | /t͡ʃə́.ɽᵊ/ | high | rise to fame, ascendancy |

| ਚੜ | چڑ | caṛ | /t͡ʃəɽ/ | level | hangnail |

Level tone is found in about 75% of words and is described by some as absence of tone. There are also some words which are said to have rising tone in the first syllable and falling in the second. (Some writers describe this as a fourth tone.) However, a recent acoustic study of six Punjabi speakers in the United States found no evidence of a separate falling tone following a medial consonant.

- ਮੋਢਾ / موڈھا, móḍà (rising-falling), "shoulder"

It is considered that these tones arose when voiced aspirated consonants (gh, jh, ḍh, dh, bh) lost their aspiration.

Mechanics

In Punjabi, tone is induced by the loss of in tonal consonants. Tonal consonants are any voiced aspirates /ʱ/ and the voiced glottal fricative /ɦ/. These include the five voiced aspirated plosives bh, dh, ḍh, jh and gh (which are represented by their own letters in Gurmukhi), the h consonant itself and any voiced consonants appended with (Gurmukhi: ੍ਹ "perī̃ hāhā", Shahmukhi: ھ "dō-caśmī hē"); usually ṛh, mh, nh, rh and lh.

- Tonal consonants induce a rising tone (also called "high tone") before them or a falling tone (also called "low tone") after them.

- E.g. kaḍḍh > káḍḍ "remove", he > è "is"

- In cases where a vowel is present on both sides of a tonal consonant, the stressed vowel receives the tone.

- E.g. paṛhāī > paṛā̀ī "study", mōḍhā > mṓḍā "shoulder"

The five tonal plosives also become voiceless word-initially. E.g. ghar > kàr "house", ḍhōl > ṭṑl "drum" etc.

Tonogenesis in Punjabi forfeits the sound of for tone. Thus, the more is realised, the less "tonal" a word will be pronounced, and vice versa. Tone is often reduced or rarely deleted when words are said with emphasis or on their own as a form of more exact identification.

Sequences with the consonant h have some additional gimmicks:

- The sequences ih, uh, ahi and ahu change into the vowels /eː˩˥/, /oː˩˥/, /ɛː˩˥/ and /ɔː˩˥/ respectively and acquire a rising tone.

- E.g. muhrā > mṓrā "chessman", rahiṇ > réṇ "stay"

- In the stressed sequence ah, the vowel lengthens (ā) and acquires a rising tone /aː˩˥/.

- E.g. qahvā > qā́vā "coffee", dah > dā́ "ten"

- In the final unstressed sequence ah, the vowel becomes nasalised and long (ā̃).

- E.g. bā́rah > bā́rā̃ "twelve", tárah > tárā̃ "way"

- When h is preceded by a short vowel, proceeded by a long vowel and the latter is stressed, the former vowel becomes weak or blends into the latter.

- E.g. pahāṛ > păā̀ṛ /pə̯aː˥˩.ɽə̆/ "mountain", tuhāḍā > tŭā̀ḍā /tʊ̯aː˥˩ɖ.ɖaː/ "your"

The consonant h on its own is now silent or very weakly pronounced except word-initially. However, certain dialects which exert stronger tone, particularly more northern Punjabi varieties and Dogri, pronounce h as very faint (thus tonal) in all cases. E.g. hatth > àtth.

The Jhangvi and Shahpuri dialects of Punjabi (as they transition into Saraiki) show comparatively less realisation of tone than other Punjabi varieties, and do not induce the devoicing of the main five tonal consonants (bh, dh, ḍh, jh, gh).

The Gurmukhi script which was developed in the 16th century has separate letters for voiced aspirated sounds, so it is thought that the change in pronunciation of the consonants and development of tones may have taken place since that time.

Some other languages in Pakistan have also been found to have tonal distinctions, including Burushaski, Gujari, Hindko, Kalami, Shina, and Torwali, though these (besides Hindko) seem to be independent of Punjabi.

Gemination

Gemination of a consonant (doubling the letter) is indicated with adhak in Gurmukhi and tashdīd in Shahmukhi. Its inscription with a unique diacritic is a distinct feature of Gurmukhi compared to Brahmic scripts.

All consonants except six (ṇ, ṛ, h, r, v, y) are regularly geminated. The latter four are only geminated in loan words from other languages.

There is a tendency to irregularly geminate consonants which follow long vowels, except in the final syllable of a word, e.g.menū̃ > mennū̃. It also causes the long vowels to shorten but remain peripheral, distinguishing them from the central vowels /ə, ɪ, ʊ/. This gemination is less prominent than the literarily regular gemination represented by the diacritics mentioned above.

Before a non-final prenasalised consonant, long vowels undergo the same change but no gemination occurs.

The true gemination of a consonant after a long vowel is unheard of but is written in some English loanwords to indicate short /ɛ/ and /ɔ/, e.g. ਡੈੱਡ ڈَیڈّ /ɖɛɖː/ "dead".

Grammar

Punjabi has a canonical word order of SOV (subject–object–verb). Function words are largely postpositions marking grammatical case on a preceding nominal.

Punjabi distinguishes two genders, two numbers, and six cases, direct, oblique, vocative, ablative, locative, and instrumental. The ablative occurs only in the singular, in free variation with oblique case plus ablative postposition, and the locative and instrumental are usually confined to set adverbial expressions.

Adjectives, when declinable, are marked for the gender, number, and case of the nouns they qualify. There is also a T-V distinction. Upon the inflectional case is built a system of particles known as postpositions, which parallel English's prepositions. It is their use with a noun or verb that is what necessitates the noun or verb taking the oblique case, and it is with them that the locus of grammatical function or "case-marking" then lies. The Punjabi verbal system is largely structured around a combination of aspect and tense/mood. Like the nominal system, the Punjabi verb takes a single inflectional suffix, and is often followed by successive layers of elements like auxiliary verbs and postpositions to the right of the lexical base.

Vocabulary

Being an Indo-Aryan language, the core vocabulary of Punjabi consists of tadbhav words inherited from Sanskrit. It contains many loanwords from Persian and Arabic.

Writing systems

| Shahmukhi alphabet |

|---|

| ا ب پ ت ٹ ث ج چ ح خ د ڈ ذ ر ڑ ز ژ س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ق ک گ ل ࣇ م ن ݨ (ں) و ه (ھ) ء ی ے |

|

Extended Perso-Arabic script |

The Punjabi language is written in multiple scripts (a phenomenon known as synchronic digraphia). Each of the major scripts currently in use is typically associated with a particular religious group, although the association is not absolute or exclusive. In India, Punjabi Sikhs use Gurmukhi, a script of the Brahmic family, which has official status in the state of Punjab. In Pakistan, Punjabi Muslims use Shahmukhi, a variant of the Perso-Arabic script and closely related to the Urdu alphabet. Sometimes Punjabi is recorded in the Devanagari script in India, albeit rarely. The Punjabi Hindus in India had a preference for Devanagari, another Brahmic script also used for Hindi, and in the first decades since independence raised objections to the uniform adoption of Gurmukhi in the state of Punjab, but most have now switched to Gurmukhi and so the use of Devanagari is rare. Often in literature, Pakistani Punjabi (written in Shahmukhi) is referred as Western-Punjabi (or West-Punjabi) and Indian Punjabi (written in Gurmukhi) is referred as Eastern-Punjabi (or East-Punjabi), although the underlying language is the same with a very slight shift in vocabulary towards Islamic and Sikh words respectively.

The written standard for Shahmukhi also slightly differs from that of Gurmukhi, as it is used for western dialects, whereas Gurumukhi is used to write eastern dialects.

Historically, various local Brahmic scripts including Laṇḍā and its descendants were also in use.

The Punjabi Braille is used by the visually impaired. There is an altered version of IAST often used for Punjabi in which the diphthongs ai and au are written as e and o, and the long vowels e and o are written as ē and ō.

Sample text

This sample text was adapted from the Punjabi Misplaced Pages article on Lahore.

ਲਹੌਰ ਪਾਕਿਸਤਾਨੀ ਪੰਜਾਬ ਦੀ ਰਾਜਧਾਨੀ ਹੈ। ਲੋਕ ਗਿਣਤੀ ਦੇ ਨਾਲ਼ ਕਰਾਚੀ ਤੋਂ ਬਾਅਦ ਲਹੌਰ ਦੂਜਾ ਸਭ ਤੋਂ ਵੱਡਾ ਸ਼ਹਿਰ ਹੈ। ਲਹੌਰ ਪਾਕਿਸਤਾਨ ਦਾ ਸਿਆਸੀ, ਕਾਰੋਬਾਰੀ ਅਤੇ ਪੜ੍ਹਾਈ ਦਾ ਗੜ੍ਹ ਹੈ ਅਤੇ ਇਸੇ ਲਈ ਇਹਨੂੰ ਪਾਕਿਸਤਾਨ ਦਾ ਦਿਲ ਵੀ ਕਿਹਾ ਜਾਂਦਾ ਹੈ। ਲਹੌਰ ਰਾਵੀ ਦਰਿਆ ਦੇ ਕੰਢੇ ’ਤੇ ਵੱਸਦਾ ਹੈ। ਇਸਦੀ ਲੋਕ ਗਿਣਤੀ ਇੱਕ ਕਰੋੜ ਦੇ ਨੇੜੇ ਹੈ।

لہور پاکستانی پنجاب دی راجدھانی ہے۔ لوک گݨتی دے نالؕ کراچی توں بعد لہور دوجا سبھ توں وڈا شہر ہے۔ لہور پاکستان دا سیاسی، رہتلی کاروباری اتے پڑھائی دا گڑھ ہے اتے، ایسے لئی ایہنوں پاکستان دا دل وی کہا جاندا ہے۔ لہور راوی دریا دے کنڈھے تے وسدا ہے۔ ایسدی لوک گݨتی اک کروڑ دے نیڑے ہے۔

Lahaur Pākistānī Panjāb dī rājtā̀ni ài. Lok giṇtī de nāḷ Karācī tõ bāad Lahaur dūjā sáb tõ vaḍḍā šáir ài. Lahaur Pākistān dā siāsī, kārobāri ate paṛā̀ī dā gáṛ ài te ise laī ínū̃ Pākistān dā dil vī kihā jāndā ài. Lahaur Rāvī dariā de káṇḍè te vassdā ài. Isdī lok giṇtī ikk karoṛ de neṛe ài.

/ləˈɔ̀ːɾᵊ pakˑɪˈstaːniː pənˈd͡ʒaːbᵊ diː ɾaːd͡ʒᵊˈtàːniː ʱɛ̀ː ‖ loːkᵊ ˈɡɪɳᵊtiː deː naːɭᵊ kəˈɾat͡ʃˑiː tõː baːədᵊ ləˈɔ̀ːɾᵊ dud͡ʒˑaː sə́bᵊ tõː ʋəɖːaː ʃɛ́ːɾ ʱɛ̀ː ‖ ləˈɔ̀ːɾᵊ pakˑɪstaːnᵊ daː sɪaːsiː | kaːɾobˑaːɾiː əteː pəɽàːiː daː ɡə́ɽ ʱɛ̀ː əteː ɪseː ləiː énˑũː pakˑɪstaːnᵊ daː dɪlᵊ ʋiː kéːa d͡ʒaːndaː ʱɛ̀ː ‖ ləˈɔ̀ːɾᵊ ɾaːʋiː ˈdəɾɪaː deː kə́ɳɖèː teː ʋəsːᵊdaː ʱɛ̀ː ‖ ˈɪsᵊdiː loːkᵊ ɡɪɳᵊtiː ɪkːᵊ kəˈɾoːɽᵊ deː neːɽeˑ ʱɛ̀ː ‖/

Translation

Lahore is the capital city of Pakistani Punjab. After Karachi, Lahore is the second largest city. Lahore is Pakistan's political, cultural, and educational hub, and so it is also said to be the heart of Pakistan. Lahore lies on the bank of the Ravi River. Its population is close to ten million people.

Literature development

Main article: Punjabi literatureMedieval period

- Fariduddin Ganjshakar (1179–1266) is generally recognised as the first major poet of the Punjabi language. Roughly from the 12th century to the 19th century, many great Sufi saints and poets preached in the Punjabi language, the most prominent being Bulleh Shah. Punjabi Sufi poetry also developed under Shah Hussain (1538–1599), Sultan Bahu (1630–1691), Shah Sharaf (1640–1724), Ali Haider (1690–1785), Waris Shah (1722–1798), Saleh Muhammad Safoori (1747–1826), Mian Muhammad Baksh (1830–1907) and Khwaja Ghulam Farid (1845–1901).

- The Sikh religion originated in the 15th century in the Punjab region and Punjabi is the predominant language spoken by Sikhs. Most portions of the Guru Granth Sahib use the Punjabi language written in Gurmukhi, though Punjabi is not the only language used in Sikh scriptures.

The Janamsakhis, stories on the life and legend of Guru Nanak (1469–1539), are early examples of Punjabi prose literature.

- The Punjabi language is famous for its rich literature of qisse, most of which are about love, passion, betrayal, sacrifice, social values and a common man's revolt against a larger system. The qissa of Heer Ranjha by Waris Shah (1706–1798) is among the most popular of Punjabi qissas. Other popular stories include Sohni Mahiwal by Fazal Shah, Mirza Sahiban by Hafiz Barkhudar (1658–1707), Sassui Punnhun by Hashim Shah (c. 1735–c. 1843), and Qissa Puran Bhagat by Qadaryar (1802–1892).

- Heroic ballads known as Vaar enjoy a rich oral tradition in Punjabi. Famous Vaars are Chandi di Var (1666–1708), Nadir Shah Di Vaar by Najabat and the Jangnama of Shah Mohammad (1780–1862).

Modern period

The Victorian novel, Elizabethan drama, free verse and Modernism entered Punjabi literature through the introduction of British education during the Raj. Nanak Singh (1897–1971), Vir Singh, Ishwar Nanda, Amrita Pritam (1919–2005), Puran Singh (1881–1931), Dhani Ram Chatrik (1876–1957), Diwan Singh (1897–1944) and Ustad Daman (1911–1984), Mohan Singh (1905–78) and Shareef Kunjahi are some legendary Punjabi writers of this period. After independence of Pakistan and India Najm Hossein Syed, Fakhar Zaman and Afzal Ahsan Randhawa, Shafqat Tanvir Mirza, Ahmad Salim, and Najm Hosain Syed, Munir Niazi, Ali Arshad Mir, Pir Hadi Abdul Mannan enriched Punjabi literature in Pakistan, whereas Jaswant Singh Kanwal (1919–2020), Amrita Pritam (1919–2005), Jaswant Singh Rahi (1930–1996), Shiv Kumar Batalvi (1936–1973), Surjit Patar (1944–) and Pash (1950–1988) are some of the more prominent poets and writers from India.

Status

Despite Punjabi's rich literary history, it was not until 1947 that it would be recognised as an official language. Previous governments in the area of the Punjab had favoured Persian, Hindustani, or even earlier standardized versions of local registers as the language of the court or government. After the annexation of the Sikh Empire by the British East India Company following the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849, the British policy of establishing a uniform language for administration was expanded into the Punjab. The British Empire employed Urdu in its administration of North-Central and Northwestern India, while in the North-East of India, Bengali language was used as the language of administration. Despite its lack of official sanction, the Punjabi language continued to flourish as an instrument of cultural production, with rich literary traditions continuing until modern times. The Sikh religion, with its Gurmukhi script, played a special role in standardising and providing education in the language via Gurdwaras, while writers of all religions continued to produce poetry, prose, and literature in the language.

In India, Punjabi is one of the 22 scheduled languages of India. It is the first official language of the Indian State of Punjab. Punjabi also has second language official status in Delhi along with Urdu, and in Haryana.

In Pakistan, no regional ethnic language has been granted official status at the national level, and as such Punjabi is not an official language at the national level, even though it is the most spoken language in Pakistan. It is widely spoken in Punjab, Pakistan, the second largest and the most populous province of Pakistan, as well as in Islamabad Capital Territory. The only two official languages in Pakistan are Urdu and English.

In Pakistan

When Pakistan was created in 1947, despite Punjabi being the majority language in West Pakistan and Bengali the majority in East Pakistan and Pakistan as whole, English and Urdu were chosen as the official languages. The selection of Urdu was due to its association with South Asian Muslim nationalism and because the leaders of the new nation wanted a unifying national language instead of promoting one ethnic group's language over another, due to this the Punjabi elites started identifying with Urdu more than Punjabi because they saw it as a unifying force on an ethnoreligious perspective. Broadcasting in Punjabi language by Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation decreased on TV and radio after 1947. Article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan declares that these two languages would be the only official languages at the national level, while provincial governments would be allowed to make provisions for the use of other languages. However, in the 1950s the constitution was amended to include the Bengali language.

Punjabi is not a language of instruction for primary or secondary school students in Punjab Province (unlike Sindhi and Pashto in other provinces). Pupils in secondary schools can choose the language as an elective, while Punjabi instruction or study remains rare in higher education. One notable example is the teaching of Punjabi language and literature by the University of the Punjab in Lahore which began in 1970 with the establishment of its Punjabi Department.

In the cultural sphere, there are many books, plays, and songs being written or produced in the Punjabi-language in Pakistan. Until the 1970s, there were a large number of Punjabi-language films being produced by the Lollywood film industry, however since then Urdu has become a much more dominant language in film production. Additionally, television channels in Punjab Province (centred on the Lahore area) are broadcast in Urdu. The preeminence of Urdu in both broadcasting and the Lollywood film industry is seen by critics as being detrimental to the health of the language.

The use of Urdu and English as the near-exclusive languages of broadcasting, the public sector, and formal education have led some to fear that Punjabi in Pakistan is being relegated to a low-status language and that it is being denied an environment where it can flourish. Several prominent educational leaders, researchers, and social commentators have echoed the opinion that the intentional promotion of Urdu and the continued denial of any official sanction or recognition of the Punjabi language amounts to a process of "Urdu-isation" that is detrimental to the health of the Punjabi language In August 2015, the Pakistan Academy of Letters, International Writer's Council (IWC) and World Punjabi Congress (WPC) organised the Khawaja Farid Conference and demanded that a Punjabi-language university should be established in Lahore and that Punjabi language should be declared as the medium of instruction at the primary level. In September 2015, a case was filed in Supreme Court of Pakistan against Government of Punjab, Pakistan as it did not take any step to implement the Punjabi language in the province. Additionally, several thousand Punjabis gather in Lahore every year on International Mother Language Day. Thinktanks, political organisations, cultural projects, and individuals also demand authorities at the national and provincial level to promote the use of the language in the public and official spheres.

In India

At the federal level, Punjabi has official status via the Eighth Schedule to the Indian Constitution, earned after the Punjabi Suba movement of the 1950s. At the state level, Punjabi is the sole official language of the state of Punjab, while it has secondary official status in the states of Haryana and Delhi. In 2012, it was also made additional official language of West Bengal in areas where the population exceeds 10% of a particular block, sub-division or district.

Both union and state laws specify the use of Punjabi in the field of education. The state of Punjab uses the Three Language Formula, and Punjabi is required to be either the medium of instruction, or one of the three languages learnt in all schools in Punjab. Punjabi is also a compulsory language in Haryana, and other states with a significant Punjabi speaking minority are required to offer Punjabi medium education.

There are vibrant Punjabi language movie and news industries in India, however Punjabi serials have had a much smaller presence within the last few decades in television up to 2015 due to market forces. Despite Punjabi having far greater official recognition in India, where the Punjabi language is officially admitted in all necessary social functions, while in Pakistan it is used only in a few radio and TV programs, attitudes of the English-educated elite towards the language are ambivalent as they are in neighbouring Pakistan. There are also claims of state apathy towards the language in non-Punjabi majority areas like Haryana and Delhi.

Advocacy

- Punjabi University was established on 30 April 1962, and is only the second university in the world to be named after a language, after Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The Research Centre for Punjabi Language Technology, Punjabi University, Patiala is working for development of core technologies for Punjabi, Digitisation of basic materials, online Punjabi teaching, developing software for office use in Punjabi, providing common platform to Punjabi cyber community. Punjabipedia, an online encyclopaedia was also launched by Patiala university in 2014.

- The Dhahan Prize was created to award literary works produced in Punjabi around the world. The Prize encourages new writing by awarding $25,000 CDN annually to one "best book of fiction" published in either of the two Punjabi scripts, Gurmukhi or Shahmukhi. Two second prizes of $5,000 CDN are also awarded, with the provision that both scripts are represented among the three winners. The Dhahan Prize is awarded by Canada India Education Society (CIES).

Governmental academies and institutes

The Punjabi Sahit academy, Ludhiana, established in 1954 is supported by the Punjab state government and works exclusively for promotion of the Punjabi language, as does the Punjabi academy in Delhi. The Jammu and Kashmir academy of art, culture and literature in Jammu and Kashmir UT, India works for Punjabi and other regional languages like Urdu, Dogri, Gojri etc. Institutions in neighbouring states as well as in Lahore, Pakistan also advocate for the language.

-

Punjabi Sahit Academy, Ludhiana, 1954

Punjabi Sahit Academy, Ludhiana, 1954

-

Punjabi Academy, Delhi, 1981–1982

Punjabi Academy, Delhi, 1981–1982

-

Jammu and Kashmir Academy of Art, Culture and Literature

Jammu and Kashmir Academy of Art, Culture and Literature

-

Punjab Institute of Language, Art and Culture, Lahore, 2004

Punjab Institute of Language, Art and Culture, Lahore, 2004

Software

- Software is available for the Punjabi language on almost all platforms. This software is mainly in the Gurmukhi script. Nowadays, nearly all Punjabi newspapers, magazines, journals, and periodicals are composed on computers via various Punjabi software programmes, the most widespread of which is InPage Desktop Publishing package. Microsoft has included Punjabi language support in all the new versions of Windows and both Windows Vista, Microsoft Office 2007, 2010 and 2013, are available in Punjabi through the Language Interface Pack support. Most Linux Desktop distributions allow the easy installation of Punjabi support and translations as well. Apple implemented the Punjabi language keyboard across Mobile devices. Google also provides many applications in Punjabi, like Google Search, Google Translate and Google Punjabi Input Tools.

Gallery

-

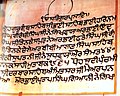

Guru Granth Sahib in Gurmukhi

Guru Granth Sahib in Gurmukhi

-

Punjabi Gurmukhi script

Punjabi Gurmukhi script

-

Punjabi Shahmukhi script

-

Bulleh Shah poetry in Punjabi (Shahmukhi script)

Bulleh Shah poetry in Punjabi (Shahmukhi script)

-

Munir Niazi poetry in Punjabi (Shahmukhi script)

Munir Niazi poetry in Punjabi (Shahmukhi script)

-

Gurmukhi alphabet

Gurmukhi alphabet

-

A sign board in Punjabi language along with Hindi at Hanumangarh, Rajasthan, India

A sign board in Punjabi language along with Hindi at Hanumangarh, Rajasthan, India

See also

- Bhangra (music) – Type of popular music associated with Punjabi culture

- Khalsa bole – coded language of Nihang Sikhs largely based on Punjabi

- List of Punjabi-language newspapers

- Punjabi cinema

- Punjabi Language Movement

Notes

- 2011 Indian Census and 2023 Pakistani Census; The figure includes the Saraiki and Hindko varieties which have been separately enumerated in Pakistani censuses since 1981 and 2017 respectively; 88.9 million , 28.8 million , 5.5 million in Pakistan (2023), 31.1 in India (2011), 0.8 in Saudi Arabia (Ethnologue), 0.6 in Canada (2016), 0.3 in the United Kingdom (2011), 0.3 in the United States (2017), 0.2 in Australia (2016) and 0.2 in the United Arab Emirates. See § Geographic distribution below.

- Paishachi, Saurasheni, or Gandhari Prakrits have been proposed as the ancestor Middle Indo-Aryan language to Punjabi.

- In blocks and divisions with at least 10% Punjabi speakers

- (/pʌnˈdʒɑːbi/ pun-JAH-bee; Shahmukhi: پنجابی; Gurmukhi: ਪੰਜਾਬੀ, Punjabi: [pəɲˈdʒab̆.bi] )

- Punjabi is the British English spelling, and Pañjābī is the Romanized spelling from the native scripts.

- 2011 Indian Census and 2023 Pakistani Census; The figure includes the Saraiki and Hindko varieties which have been separately enumerated in Pakistani censuses since 1981 and 2017 respectively; 88.9 million , 28.8 million , 5.5 million in Pakistan (2023), 31.1 in India (2011), 0.8 in Saudi Arabia (Ethnologue), 0.6 in Canada (2016), 0.3 in the United Kingdom (2011), 0.3 in the United States (2017), 0.2 in Australia (2016) and 0.2 in the United Arab Emirates. See § Geographic distribution below.

- Standard or Eastern dialect. Pakistani Majhi and Western dialects usually pronounce it as /käː˨ɾᵊ/.

- /jː/ is found in one other instance, for the name of the Gurmukhi letter ਯ (yayyā ਯੱਯਾ)

- This never occurs with /ɳ/ and /ɽ/, and is rare before /ʋ, ɾ, ɦ/

- bindī/ṭippī or nūn ġunna before a consonant often causes it to be pre-nasalised, except where there is a true nasal vowel.

References

Citations

- ^ Singh, Sikander (April 2019). "The Origin Theories of Punjabi Language: A Context of Historiography of Punjabi Language". International Journal of Sikh Studies.

- ^ Haldar, Gopal (2000). Languages of India. New Delhi: National Book Trust, India. p. 149. ISBN 9788123729367.

The age of Old Punjabi: up to 1600 A.D. It is said that evidence of Old Punjabi can be found in the Granth Sahib.

- ^ Bhatia, Tej K. (2013). Punjabi: A Cognitive-Descriptive Grammar (Reprint ed.). London: Routledge. p. XXV. ISBN 9781136894602.

As an independent language Punjabi has gone through the following three stages of development: Old Punjabi (10th to 16th century). Medieval Punjabi (16th to 19th century), and Modern Punjabi (19th century to Present).

- ^ Christopher Shackle; Arvind Mandair (2013). "0.2.1 – Form". Teachings of the Sikh Gurus : selections from the Scriptures (First ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 9781136451089.

Surpassing them all in the frequent subtlety of his linguistic choices, including the use of dialect forms as well as of frequent loanwords from Sanskrit and Persian, Guru Nanak combined this poetic language of the Sants with his native Old Punjabi. It is this mixture of Old Punjabi and Old Hindi which constitutes the core idiom of all the earlier Gurus.

- ^ Frawley, William (2003). International encyclopedia of linguistics (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 423. ISBN 9780195139778.

- ^ Austin, Peter (2008). One thousand languages : living, endangered, and lost. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780520255609.

- ^ Braj B. Kachru; Yamuna Kachru; S. N. Sridhar (2008). Language in South Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 411. ISBN 9781139465502.

- "NCLM 52nd Report" (PDF). NCLM. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Punjab mandates all signage in Punjabi, in Gurmukhi script". The Hindu. 21 February 2020. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "All milestones, signboards in Haryana to bear info in English, Hindi and Punjabi: Education Minister". The Indian Express. 3 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "Punjabi, Urdu made official languages in Delhi". The Times of India. 25 June 2003. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Multi-lingual Bengal". The Telegraph. 11 December 2012. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- India, Tribune (19 August 2020). "Punjabi matric exam on Aug 26". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student's Handbook, Edinburgh

- Mangat Rai Bhardwaj (2016). Panjabi: A Comprehensive Grammar. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-138-79385-9. LCCN 2015042069. OCLC 948602857. OL 35828315M. Wikidata Q23831241.

- "The World Factbook - WORLD". CIA. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- Canfield, Robert L. (1991). Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 1 ("Origins"). ISBN 978-0-521-52291-5.

- Sir, Yule, Henry (13 August 2018). "Hobson-Jobson: A glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive". dsalsrv02.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Macdonell, Arthur Anthony (13 August 2018). "A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary with Transliteration, Accentuation, and Etymological Analysis Throughout". Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- Singha, H. S. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries). Hemkunt Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-81-7010-301-1. Archived from the original on 21 January 2017.

- G S Sidhu (2004). Panjab And Panjabi.

- ^ Hoiberg, Dale (2000). Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- Murphy, Anne (29 November 2020). "13: The Territorialisation of Sikh Pasts". In Jacobsen, Knut A. (ed.). Routledge Handbook of South Asian Religions. Routledge. pp. 206–207. ISBN 9780429622069.

- Brard, G.S.S. (2007). East of Indus: My Memories of Old Punjab. Hemkunt Publishers. p. 81. ISBN 9788170103608. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Mir, F. (2010). The Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab. University of California Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780520262690. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Schiffman, H. (2011). Language Policy and Language Conflict in Afghanistan and Its Neighbors: The Changing Politics of Language Choice. Brill. p. 314. ISBN 9789004201453. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Schiffman, Harold (9 December 2011). Language Policy and Language Conflict in Afghanistan and Its Neighbors: The Changing Politics of Language Choice. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-20145-3. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- Menon, A.S.; Kusuman, K.K. (1990). A Panorama of Indian Culture: Professor A. Sreedhara Menon Felicitation Volume. Mittal Publications. p. 87. ISBN 9788170992141. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Population Census Organization". Archived from the original on 26 September 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- "CCI defers approval of census results until elections". Dawn. 21 March 2021. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2021. The figure of 80.54 million is calculated from the reported 38.78% for the speakers of Punjabi and the 207.685 million total population of Pakistan.

- ^ "Punjabi is 4th most spoken language in Canada". The Times of India. 14 February 2008. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016.

- "Statement 1 : Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues – 2011" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- "Growth of Scheduled Languages-1971, 1981, 1991 and 2001". Census of India. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- Government of Canada (9 February 2022). "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - Canada [Country] - Mother tongue". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- 273,000 in England and Wales, and 23,000 in Scotland:

- "2011 Census: Quick Statistics for England and Wales, March 2011". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "Table AT_002_2011 – Language used at home other than English (detailed), Scotland". Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "US survey puts Punjabi speakers in US at 2.8 lakh". The Times of India. 18 December 2017. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- "Glottolog 4.8 - Greater Panjabic". glottolog.org. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- Punjabi language at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023) [REDACTED]

- Shackle 1979, p. 198.

- Zograph, G. A. (2023). "Chapter 3". Languages of South Asia: A Guide (Reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 52. ISBN 9781000831597.

LAHNDA – Lahnda (Lahndi) or Western Panjabi is the name given to a group of dialects spread over the northern half of Pakistan. In the north, they come into contact with the Dardic languages with which they share some common features, In the east, they turn gradually into Panjabi, and in the south into Sindhi. In the south-east there is a clearly defined boundary between Lahnda and Rajasthani, and in the west a similarly well-marked boundary between it and the Iranian languages Baluchi and Pushtu. The number of people speaking Lahnda can only be guessed at: it is probably in excess of 20 million.

- Shackle 2003, p. 587.

- Shackle 2003, p. 588.

- Karamat, Nayyara, Phonemic inventory of Punjabi, p. 182, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.695.1248

- ^ Used in conjunction with another consonant, commonly ج or ی

- ArLaam (similar to ArNoon) has been added to Unicode since Unicode 13.0.0, which can be found in Unicode Archived 28 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine Arabic Extended-A 08C7, PDF Pg 73 under "Arabic Letter for Punjabi" 08C7 : ࣇ Arabic Letter Lam With Small Arabic Letter Tah Above

- Shackle 2003, p. 589.

- Masica 1991, p. 97.

- Arora, K. K.; Arora, S.; Singla, S. R.; Agrawal, S. S. (2007). "SAMPA for Hindi and Punjabi based on their Acoustic and Phonetic Characteristics". Proceedings Oriental COCOSDA: 4–6. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-0631198154.

- Bhatia, Tej (1999). "Lexican Anaphors and Pronouns in Punjabi". In Lust, Barbara; Gair, James (eds.). Lexical Anaphors and Pronouns in Selected South Asian Languages. Walter de Gruyter. p. 637. ISBN 978-3-11-014388-1. Other tonal Indo-Aryan languages include Hindko, Dogri, Western Pahari, Sylheti and some Dardic languages.

- ^ Bailey, T.Grahame (1919), English-Punjabi Dictionary, introduction.

- Singh, Sukhvindar, "Tone Rules and Tone Sandhi in Punjabi".

- ^ Bowden, A.L. (2012). "Punjabi Tonemics and the Gurmukhi Script: A Preliminary Study" Archived 17 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- Major Gurmukh Singh; Shiv Sharma Joshi; Mukhtiar Singh Gill; Manmandar Singh; Kuljit Kapur; Suman Preet, eds. (2018), Punjabi University Punjabi-English Dictionary (ਛੇਵੀਂ ed.), Patiala: Publication Bureau, Punjabi University, Wikidata Q113676548

- Punjabi University (2018). p. 281

- Punjabi University (2018). p. 194

- Punjabi University (2018). p. 192

- Punjabi University (2018). p. 369

- ^ Punjabi University (2018). p. 300

- Kanwal, J.; Ritchart, A.V (2015) "An experimental investigation of tonogenesis in Punjabi". Archived 18 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine Proceedings of the 18th International of Phonetic Sciences, 2015

- Lata, Swaran; Arora, Swati (2013) "Laryngeal Tonal characteristics of Punjabi: An Experimental Study" Archived 18 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Baart, J.L.G. "Tonal features in languages of northern Pakistan" Archived 28 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Masica 1991, p. 149.

- Gill, Harjeet Singh and Gleason Jr, Henry A. (1969). A Reference Grammar of Panjabi. Patiala: Department of Linguistics, Punjabi University

- "WALS Online – Language Panjabi". wals.info. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- Shackle (2003:599)

- Shackle (2003:601)

- Masica (1991:257)

- ^ Frawley, William (2003). International Encyclopedia of Linguistics: 4-Volume Set. Oxford University Press. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-19-513977-8.

Hindus and Sikhs generally use the Gurmukhi script; but Hindus have also begun to write Punjabi in the Devanagari script, as employed for Hindi. Muslims tend to write Punjabi in the Perso-Arabic script, which is also employed for Urdu. Muslim speakers borrow a large number of words from Persian and Arabic; however, the basic Punjabi vocabulary is mainly composed of tadbhava words, i.e. those descended from Sanskrit.

- Bhatia, Tej K. (1993). Punjabi: A Conginitive-descriptive Grammar. Psychology Press. p. xxxii. ISBN 978-0-415-00320-9.

Punjabi vocabulary is mainly composed of tadbhav words, i.e., words derived from Sanskrit.

- Bhatia 2008, p. 128.

- Bhardwaj 2016, pp. 12–13.

- Jain 2003, pp. 53, 57–8.

- Zograph, G. A. (2023). "Chapter 3". Languages of South Asia: A Guide (Reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 52. ISBN 9781000831597.

Devanagari itself is also used for Panjabi, if more rarely.

- Nayar 1966, pp. 46 ff.

- Bhardwaj 2016, p. 12.

- ^ Shackle 2003, p. 594.

- "Punjabi Language – Structure, Writing & Alphabet – MustGo". MustGo.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Bhardwaj 2016, p. 15.

- Shiv Kumar Batalvi Archived 10 April 2003 at the Wayback Machine sikh-heritage.co.uk.

- Melvin Ember; Carol R. Ember; Ian A. Skoggard, eds. (2005). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Springer. p. 1077. ISBN 978-0-306-48321-9.

- Mir, Farina. "Representations of Piety and Community in Late-nineteenth-century Punjabi Qisse". Columbia University. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature (Volume One – A to Devo). Volume 1. Amaresh Datta, ed. Sahitya Akademi: 2006, 352.

- Hussain, Fayyaz; Khan, Muhammad Asim; Khan, Hina (2018). "The implications of trends in Punjabi: As a covert and/or an overt Prestige in Pakistan". Kashmir Journal of Language Research. 21 (2): 59–75. doi:10.46896/jicc.v3i01.188 (inactive 1 November 2024). Archived from the original on 19 April 2024. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

Punjabi in Pakistan language that is numerically prevalent.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - "Facts about Pakistan". opr.gov.pk. Government of Pakistan – Office of the Press Registrar. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- Ahmed, Ishtiaq (14 July 2020). "Why Punjabis in Pakistan Have Abandoned Punjabi". Fair Observer. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- "Chapter 4: "General." of Part XII: "Miscellaneous"". pakistani.org. Archived from the original on 3 June 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Zaidi, Abbas. "Linguistic cleansing: the sad fate of Punjabi in Pakistan". Archived from the original on 29 October 2016.

- University of the Punjab (2015), "B.A. Two-Year (Pass Course) Examinations"

- "University of the Punjab – Examinations". pu.edu.pk. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- University of the Punjab (2015). "Department of Punjabi". Archived from the original on 27 November 2016.

- Masood, Tariq (21 February 2015). "The colonisation of language". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- Warraich, Faizan; Ali, Haider (15 September 2015). "Intelligentsia urges govt to promote Punjabi language". DailyTimes. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "Punjabis Without Punjabi". apnaorg.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Inferiority complex declining Punjabi language: Punjab University Vice-Chancellor". PPI News Agency

- "Inferiority complex declining Punjabi language: Punjab University Vice-Chancellor | Pakistan Press International". ppinewsagency.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Urdu-isation of Punjab – The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 4 May 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "Rally for ending 150-year-old 'ban on education in Punjabi". The Nation. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "Sufi poets can guarantee unity". The Nation. 26 August 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015.

- "Supreme Court's Urdu verdict: No language can be imposed from above". The Nation. 15 September 2015. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "Two-member SC bench refers Punjabi language case to CJP". Business Recorder. 14 September 2015. Archived from the original on 21 October 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "Mind your language—The movement for the preservation of Punjabi". The Herald. 2 September 2106.

- "Mind your language—The movement for the preservation of Punjabi – People & Society – Herald". herald.dawn.com. 4 August 2016. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Punjabi in schools: Pro-Punjabi outfits in Pakistan threaten hunger strike". The Times of India. 4 October 2015.

- "Punjabi in schools: Pro-Punjabi outfits in Pakistan threaten hunger strike". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Rally for Ending the 150-year-old Ban on Education in Punjabi" The Nation. 21 February 2011.

- "Rally for ending 150-year-old 'ban on education in Punjabi". nation.com.pk. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Khokhlova, Liudmila (January 2014). "Majority Language Death" (PDF). Language Endangerment and Preservation in South Asia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

Punjabi was nonetheless included in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India and came to be recognized as one of the fifteen official languages of the country.

- "Fifty Years of Punjab Politics (1920–70)". Panjab Digital Library. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Ayres, Alyssa (2008). "Language, the Nation, and Symbolic Capital: The Case of Punjab" (PDF). The Journal of Asian Studies. 67 (3): 917–946. doi:10.1017/S0021911808001204. S2CID 56127067. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

in India, Punjabi is an official language as well as the first language of the state of Punjab (with secondary status in Delhi and widespread use in Haryana).

- Kumar, Ashutosh (2004). "Electoral Politics in Punjab: Study of Akali Dal". Economic & Political Weekly. 39 (14/15): 1515–1520. JSTOR 4414869.

Punjabi was made the first compulsory language and medium of instruction in all the government schools whereas Hindi and English as second and third language were to be implemented from the class 4 and 6 respectively

- 52nd Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India (PDF) (Report). National Commission on Linguistic Minorities. 2015. p. 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

Languages taught in the State under the Three Language Formula: First Language : Hindi Second Language : Punjabi Third language : English

- Singh, Jasmine (13 September 2015). "Serial killer". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "SGPC claims Haryana govt ignoring Punjabi language". Hindustan Times. 30 July 2015. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- Aujla, Harjap Singh (15 June 2015). "Punjabi's of Delhi couldn't get justice for Punjabi language". Punjab News Express. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- Singh, Perneet (9 July 2013). "Sikh bodies oppose DU's 'anti-Punjabi' move". Tribune India. Archived from the original on 19 May 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "final". punjabiuniversity.ac.in. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "ACTDPL, Punjabi University, Patiala". learnpunjabi.org. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਪੀਡੀਆ". punjabipedia.org. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Pbi University launches Punjabipedia | punjab | Hindustan Times". Hindustan Times. 26 February 2014. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "The Dhahan Prize | The Dhahan Prize for Punjabi Literature". dhahanprize.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਲੇਖਕਾਂ ਦਾ ਮੱਕਾ : ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਭਵਨ, ਲੁਧਿਆਣਾ". 3 May 2017. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- "Sirsa again elected Punjabi Sahit Akademi president". Tribuneindia.com. 18 April 2016. Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Punjabi Academy". www.punjabiacademy.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2017.

- "JK Cultural Academy". jkculture.nic.in. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016.

- "पंजाबी सीखने वाले छात्रों को अगले माह बटेगा एकल प्रोत्साहन राशि". M.livehindustan.com. 24 October 2016. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Welcome to Punjab Institute of Language, Art & Culture | Punjab Institute of Language, Art & Culture". pilac.punjab.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017.

- "Microsoft Download Center". microsoft.com. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Punjabi Linux (punlinux) download | SourceForge.net". sourceforge.net. 21 April 2013. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Connecting to the iTunes Store". itunes.apple.com. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Google". Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Google ਅਨੁਵਾਦ". Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Cloud ਇਨਪੁਟ ਔਜ਼ਾਰ ਔਨਲਾਈਨ ਅਜਮਾਓ – Google ਇਨਪੁਟ ਔਜ਼ਾਰ". Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

Sources

- Bhardwaj, Mangat Rai (2016), Panjabi: A Comprehensive Grammar, Routledge, doi:10.4324/9781315760803, ISBN 9781138793859.

- Bhatia, Tej K. (2008), "Major regional languages", in Braj B. Kachru; Yamuna Kachru; S.N. Sridhar (eds.), Language in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, pp. 121–131, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511619069.008, ISBN 9780511619069.

- Grierson, George A. (1916). Linguistic Survey of India. Vol. IX Indo-Aryan family. Central group, Part 1, Specimens of western Hindi and Pañjābī. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India.

- Jain, Dhanesh (2003), "Sociolinguistics of the Indo-Aryan Languages", in Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, pp. 46–66, ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

- Masica, Colin (1991), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2, archived from the original on 2 April 2023, retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Nayar, Baldev Raj (1966), Minority Politics in the Punjab, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9781400875948, archived from the original on 2 April 2023, retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Rao, Aparna (1995). "Marginality and language use: the example of peripatetics in Afghanistan". Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society. 5 (2): 69–95.

- Shackle, Christopher (1979). "Problems of classification in Pakistan Panjab". Transactions of the Philological Society. 77 (1): 191–210. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.1979.tb00857.x. ISSN 0079-1636.

- Shackle, Christopher (2003), "Panjabi", in Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, pp. 581–621, ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5, archived from the original on 2 April 2023, retrieved 7 October 2020.

Further reading

- Bhatia, Tej. 1993 and 2010. Punjabi : a cognitive-descriptive grammar. London: Routledge. Series: Descriptive grammars.

- Gill H.S. and Gleason, H.A. 1969. A reference grammar of Punjabi. Revised edition. Patiala, Punjab, India: Languages Department, Punjab University.

- Chopra, R. M., Perso-Arabic Words in Punjabi, in: Indo-Iranica Vol.53 (1–4).

- Chopra, R. M.., The Legacy of The Punjab, 1997, Punjabee Bradree, Calcutta.

- Singh, Chander Shekhar (2004). Punjabi Prosody: The Old Tradition and The New Paradigm. Sri Lanka: Polgasowita: Sikuru Prakasakayo.

- Singh, Chander Shekhar (2014). Punjabi Intonation: An Experimental Study. Muenchen: LINCOM EUROPA.

External links

- English to Punjabi Dictionary Archived 10 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Proposal to encode ARABIC LETTER NOON WITH RING ABOVE at the Unicode Website

| Punjabi language topics | |

|---|---|

| Languages of India | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official languages |

| ||||||||||

| Major unofficial languages |

| ||||||||||

| Languages of Pakistan | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official languages | |||||||||||||

| Other languages (by administrative unit) |

| ||||||||||||

| Related topics | |||||||||||||

| Indo-Aryan languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dardic |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Northern |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Northwestern |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Western |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Central |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eastern |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Southern |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Middle |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proto- languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unclassified |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pidgins and creoles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pakistan articles | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

- Punjabi language

- Fusional languages

- Greater Punjabi languages and dialects

- Languages of Pakistan

- Languages of Punjab, Pakistan

- Languages written in Brahmic scripts

- Languages written in Devanagari

- Official languages of India

- Punjab

- Punjabi culture

- Subject–object–verb languages

- Tonal languages in non-tonal families