Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India, Nepal, and Syria, cremation on an open-air pyre is an ancient tradition. Starting in the 19th century, cremation was introduced or reintroduced into other parts of the world. In modern times, cremation is commonly carried out with a closed furnace (cremator), at a crematorium.

Cremation leaves behind an average of 2.4 kg (5.3 lb) of remains known as ashes or cremains. This is not all ash but includes unburnt fragments of bone mineral, which are commonly ground into powder. They are inorganic and inert, and thus do not constitute a health risk and may be buried, interred in a memorial site, retained by relatives or scattered in various ways.

History

Ancient

Further information: Secondary cremation

Cremation dates from at least 17,000 years ago in the archaeological record, with the Mungo Lady, the remains of a partly cremated body found at Lake Mungo, Australia.

Alternative death rituals which emphasize one method of disposal – burial, cremation, or exposure – have gone through periods of preference throughout history.

In the Middle East and Europe, both burial and cremation are evident in the archaeological record in the Neolithic era. Cultural groups had their own preferences and prohibitions. The ancient Egyptians developed an intricate transmigration-of-soul theology, which prohibited cremation. This was also widely adopted by Semitic peoples. The Babylonians, according to Herodotus, embalmed their dead. Phoenicians practiced both cremation and burial. From the Cycladic civilization in 3000 BCE until the Sub-Mycenaean era in 1200–1100 BCE, Greeks practiced burial. Cremation appeared around the 12th century BCE, probably influenced by Anatolia. Until the Christian era, when inhumation again became the only burial practice, both combustion and inhumation had been practiced, depending on the era and location. In Rome's earliest history, both inhumation and cremation were in common use among all classes. Around the mid-Republic, inhumation was almost exclusively replaced by cremation, with some notable exceptions, and remained the most common funerary practice until the middle of the Empire, when it was almost entirely replaced by inhumation.

In Europe, there are traces of cremation dating to the Early Bronze Age (c. 2000 BCE) in the Pannonian Plain and along the middle Danube. The custom became dominant throughout Bronze Age Europe with the Urnfield culture (from c. 1300 BCE). In the Iron Age, inhumation again becomes more common, but cremation persisted in the Villanovan culture and elsewhere. Homer's account of Patroclus' burial describes cremation with subsequent burial in a tumulus, similar to Urnfield burials, and qualifying as the earliest description of cremation rites. This may be an anachronism, as during Mycenaean times burial was generally preferred, and Homer may have been reflecting the more common use of cremation at the time the Iliad was written, centuries later.

Criticism of burial rites is a common aspersion by competing religions and cultures, including the association of cremation with fire sacrifice or human sacrifice.

Hinduism and Jainism are notable for not only allowing but prescribing cremation. Cremation in India is first attested in the Cemetery H culture (from c. 1900 BCE), considered the last phase of Indus Valley Civilisation and beginning of the Vedic civilization. The Rigveda contains a reference to the emerging practice, in RV 10.15.14, where the forefathers "both cremated (agnidagdhá-) and uncremated (ánagnidagdha-)" are invoked.

Cremation remained common but not universal, in both ancient Greece and ancient Rome. According to Cicero, burial was considered the more archaic rite in Rome.

The rise of Christianity saw an end to cremation in Europe, though it may have already been in decline.

In early Roman Britain, cremation was usual but diminished by the 4th century. It then reappeared in the 5th and 6th centuries during the migration era, when sacrificed animals were sometimes included on the pyre, and the dead were dressed in costume and with ornaments for the burning. That custom was also very widespread among the Germanic peoples of the northern continental lands from which the Anglo-Saxon migrants are supposed to have been derived, during the same period. These ashes were usually thereafter deposited in a vessel of clay or bronze in an "urn cemetery". The custom again died out with the Christian conversion of the Anglo-Saxons or Early English during the 7th century, when Christian burial became general.

Middle Ages

In parts of Europe, cremation was forbidden by law, and even punishable by death if combined with Heathen rites. Cremation was sometimes used by Catholic authorities as part of punishment for accused heretics, which included burning at the stake. For example, the body of John Wycliff was exhumed years after his death and burned to ashes, with the ashes thrown in a river, explicitly as a posthumous punishment for his denial of the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation.

The first to advocate for the use of cremation was the physician Sir Thomas Browne in Urne Buriall (1658) which interpreted cremation as means of oblivion and reveals plainly that "'there is no antidote against the Opium of time...". Honoretta Brooks Pratt became the first recorded cremated European individual in modern times when she died on 26 September 1769 and was illegally cremated at the burial ground on Hanover Square in London.

Reintroduction

In Europe, a movement to reintroduce cremation as a viable method for body disposal began in the 1870s. This was made possible by the invention of new furnace technology and contact with eastern cultures that practiced it. At the time, many proponents believed in the miasma theory, and that cremation would reduce the "bad air" that caused diseases. These movements were associated with secularism and gained a following in cultural and intellectual circles. In Italy, the movement was associated with anti-clericalism and Freemasonry, whereas these were not major themes of the movement in Britain.

In 1869, the idea was presented to the Medical International Congress of Florence by Professors Coletti and Castiglioni "in the name of public health and civilization". In 1873, Professor Paolo Gorini of Lodi and Professor Ludovico Brunetti of Padua published reports of practical work they had conducted. A model of Brunetti's cremating apparatus, together with the resulting ashes, was exhibited at the Vienna Exposition in 1873 and attracted great attention Meanwhile, Sir Charles William Siemens had developed his regenerative furnace in the 1850s. His furnace operated at a high temperature by using regenerative preheating of fuel and air for combustion. In regenerative preheating, the exhaust gases from the furnace are pumped into a chamber containing bricks, where heat is transferred from the gases to the bricks. The flow of the furnace is then reversed so that fuel and air pass through the chamber and are heated by the bricks. Through this method, an open-hearth furnace can reach temperatures high enough to melt steel, and this process made cremation an efficient and practical proposal. Charles's nephew, Carl Friedrich von Siemens perfected the use of this furnace for the incineration of organic material at his factory in Dresden. The radical politician, Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke, took the corpse of his dead wife there to be cremated in 1874. The efficient and cheap process brought about the quick and complete incineration of the body and was a fundamental technical breakthrough that finally made industrial cremation a practical possibility.

The first crematorium in the Western World opened in Milan in 1876. Milan's "Crematorium Temple" was built in the Monumental Cemetery. The building still stands but ceased to be operational in 1992.

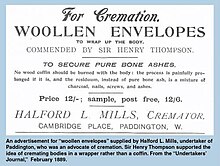

Sir Henry Thompson, 1st Baronet, a surgeon and Physician to the Queen Victoria, had seen Gorini's cremator at the Vienna Exhibition and had returned home to become the first and chief promoter of cremation in England. His main reason for supporting cremation was that "it was becoming a necessary sanitary precaution against the propagation of disease among a population daily growing larger in relation to the area it occupied". In addition, he believed, cremation would prevent premature burial, reduce the expense of funerals, spare mourners the necessity of standing exposed to the weather during interment, and urns would be safe from vandalism. He joined with other proponents to form the Cremation Society of Great Britain in 1874." They founded the United Kingdom's first crematorium in Woking, with Gorini travelling to England to assist the installation of a cremator. They first tested it on 17 March 1879 with the body of a horse. After protests and an intervention by the Home Secretary, Sir Richard Cross, their plans were put on hold. In 1884, the Welsh Neo-Druidic priest William Price was arrested and put on trial for attempting to cremate his son's body. Price successfully argued in court that while the law did not state that cremation was legal, it also did not state that it was illegal. The case set a precedent that allowed the Cremation Society to proceed.

In 1885, the first official cremation in the United Kingdom took place in Woking. The deceased was Jeanette Pickersgill, a well-known figure in literary and scientific circles. By the end of the year, the Cremation Society of Great Britain had overseen 2 more cremations, a total of 3 out of 597,357 deaths in the UK that year. In 1888, 28 cremations took place at the venue. In 1891, Woking Crematorium added a chapel, pioneering the concept of a crematorium being a venue for funerals as well as cremation.

Other early crematoria in Europe were built in 1878 in the town of Gotha in Germany and later in Heidelberg in 1891. The first modern crematory in the U.S. was built in 1876 by Francis Julius LeMoyne after hearing about its use in Europe. Like many early proponents, he was motivated by a belief it would be beneficial for public health. Before LeMoyne's crematory closed in 1901, it had performed 42 cremations. Other countries that opened their first crematorium included Sweden (1887 in Stockholm), Switzerland (1889 in Zurich) and France (1889 in Père Lachaise, Paris).

Western spread

Some of the various Protestant churches came to accept cremation. In Anglican and Nordic Protestant countries, cremation gained acceptance (though it did not yet become the norm) first by the upper classes and cultural circles, and then by the rest of the population. In 1905, Westminster Abbey interred ashes for the first time; by 1911 the Abbey was expressing a preference for interring ashes. The 1908 Catholic Encyclopedia was critical of the development, referring to them as a "sinister movement" and associating them with Freemasonry, although it said that "there is nothing directly opposed to any dogma of the Church in the practice of cremation."

In the U.S. only about one crematory per year was built in the late 19th century. As embalming became more widely accepted and used, crematories lost their sanitary edge. Not to be left behind, crematories had an idea of making cremation beautiful. They started building crematories with stained-glass windows and marble floors with frescoed walls.

Australia also started to establish modern cremation movements and societies. Australians had their first purpose-built modern crematorium and chapel in the West Terrace Cemetery in the South Australian capital of Adelaide in 1901. This small building, resembling the buildings at Woking, remained largely unchanged from its 19th-century style and was in full operation until the late 1950s. The oldest operating crematorium in Australia is at Rookwood Cemetery, in Sydney. It opened in 1925.

In the Netherlands, the foundation of the Association for Optional Cremation in 1874 ushered in a long debate about the merits and demerits of cremation. Laws against cremation were challenged and invalidated in 1915 (two years after the construction of the first crematorium in the Netherlands), though cremation did not become legally recognised until 1955.

World War II

During World War II (1939–45), Nazi Germany used specially built furnaces in at least six extermination camps throughout occupied Poland including at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Chełmno, Belzec, Majdanek, Sobibor and Treblinka, where the bodies of those murdered by gassing were disposed of using incineration. The efficiency of industrialised killing of Operation Reinhard during the most deadly phase of the Holocaust produced too many corpses, therefore the crematoria manufactured to SS specifications were put into use in all of them to handle the disposals around the clock, day and night. The Vrba–Wetzler report offers the following description.

At present there are four crematoria in operation at BIRKENAU, two large ones, I and II, and two smaller ones, III and IV. Those of type I and II consist of 3 parts, i.e.,: (A) the furnace room; (B) the large halls; and (C) the gas chamber. A huge chimney rises from the furnace room around which are grouped nine furnaces, each having four openings. Each opening can take three normal corpses at once and after an hour and a half the bodies are completely burned. This corresponds to a daily capacity of about 2,000 bodies... Crematoria III and IV work on nearly the same principle, but their capacity is only half as large. Thus the total capacity of the four cremating and gassing plants at BIRKENAU amounts to about 6,000 daily.

The Holocaust furnaces were supplied by a number of manufacturers, with the best known and most common being Topf and Sons as well as Kori Company of Berlin, whose ovens were elongated to accommodate two bodies, slid inside from the back side. The ashes were taken out from the front side.

Modern era

See also: List of countries by cremation rateIn the 20th century, cremation gained varying degrees of acceptance in most Christian denominations. William Temple, the most senior bishop in the Church of England, was cremated after his death in office in 1944. The Roman Catholic Church accepted the practice more slowly. In 1963, at the Second Vatican Council Pope Paul VI lifted the ban on cremation, and in 1966 allowed Catholic priests to officiate at cremation ceremonies. This is done on the condition that the ashes must be buried or interred, not scattered. Many countries where burial is traditional saw cremation rise to become a significant, if not the most common way of disposing of a dead body. In the 1960s and 1970s, there was an unprecedented phase of crematorium construction in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands.

Starting in the 1960s, cremation has become more common than burial in several countries where the latter is traditional. This has included the United Kingdom (1968), Czechoslovakia (1980), Canada (early 2000s), the United States (2016) and Finland (2017). Factors cited include cheaper costs (especially a factor after the 2008 recession), growth in secular attitudes and declining opposition in some Christian denominations.

Modern process

The cremation occurs in a cremator, which is located at a crematorium or crematory. In many countries, the crematorium is a venue for funerals as well as cremation.

A cremator is an industrial furnace that is able to generate temperatures of 871–982 °C (1,600–1,800 °F) to ensure the disintegration of the corpse. Modern cremator fuels include oil, natural gas, propane, and, in Hong Kong, coal gas. Modern cremators automatically monitor their interior to tell when the cremation process is complete and have a spyhole so that an operator can see inside. The time required for cremation varies from body to body, with the average being 90 minutes for an adult body.

The chamber where the body is placed is called a cremation chamber or retort and is lined with heat-resistant refractory bricks. Refractory bricks are designed in several layers. The outermost layer is usually simply an insulation material, e.g., mineral wool. Inside is typically a layer of insulation brick, mostly calcium silicate in nature. Heavy duty cremators are usually designed with two layers of fire bricks inside the insulation layer. The layer of fire bricks in contact with the combustion process protects the outer layer and must be replaced from time to time.

The body is generally required to be inside a coffin or a combustible container. This allows the body to be quickly and safely slid into the cremator. It also reduces health risks to the operators. The coffin or container is inserted (charged) into the cremator as quickly as possible to avoid heat loss. Some crematoria allow relatives to view the charging. This is sometimes done for religious reasons, such as in traditional Hindu and Jain funerals, and is also customary in Japan.

Body container

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In the United States federal law does not dictate any container requirements for cremation. Certain states require an opaque or non-transparent container for all cremations. This can be a simple corrugated cardboard box or a wooden casket (coffin). Another option is a cardboard box that fits inside a wooden shell, which is designed to look like a traditional casket. After the funeral service, the box is removed from the shell before cremation, permitting the shell to be re-used.

In the United Kingdom, the body is not removed from the coffin and is not placed into a container as described above. The body is cremated with the coffin which is why all British coffins that are to be used for cremation must be combustible. The Code of Cremation Practice forbids the opening of the coffin once it has arrived at the crematorium, and rules stipulate that it must be cremated within 72 hours of the funeral service. Therefore, in the United Kingdom, bodies are cremated in the same coffin that they are placed in at the undertaker's, although the regulations allow the use of an approved "cover" during the funeral service. It is recommended that jewellery be removed before the coffin is sealed, for this reason. When cremation is finished, the remains are passed through a magnetic field to remove any metal, which will be interred elsewhere in the crematorium grounds or, increasingly, recycled. The ashes are entered into a cremulator to further grind the remains down into a finer texture before being given to relatives or loved ones or scattered in the crematorium grounds where facilities exist.

In Germany, the process is mostly similar to that of the United Kingdom. The body is cremated in the coffin. A piece of fire clay with a number on it is used for identifying the remains of the dead body after burning. The remains are then placed in a container called an ash capsule, which generally is put into a cinerary urn.

In Australia, reusable or cardboard coffins are rare, with only a few manufacturers now supplying them. For low cost, a plain, particle-board coffin (known in the trade as a "chippie", "shipper" or "pyro") can be used. Handles (if fitted) are plastic and approved for use in a cremator.

Cremations can be "delivery only", with no preceding chapel service at the crematorium (although a church service may have been held) or preceded by a service in one of the crematorium chapels. Delivery-only allows crematoria to schedule cremations to make best use of the cremators, perhaps by holding the body overnight in a refrigerator, allowing a lower fee to be charged.

Burning and ash collection

See also: Ball mill-

(Germany) A piece of fire clay used for identifying the ash after burning the dead body

(Germany) A piece of fire clay used for identifying the ash after burning the dead body

-

(Germany) A cinerary urn. The laces are used to lower the urn into the ground

(Germany) A cinerary urn. The laces are used to lower the urn into the ground

-

(Germany) A sealed cinerary urn, showing the ash capsule containing the remains of the dead, along with the name and dates

(Germany) A sealed cinerary urn, showing the ash capsule containing the remains of the dead, along with the name and dates

-

(Germany) The ash capsule

(Germany) The ash capsule

-

(Germany) An open ash capsule showing the remains of the dead

(Germany) An open ash capsule showing the remains of the dead

-

(Germany) Ash capsule and cinerary urn after 15 years

(Germany) Ash capsule and cinerary urn after 15 years

The box containing the body is placed in the retort and incinerated at a temperature of 760 to 1,150 °C (1,400 to 2,100 °F). During the cremation process, the greater portion of the body (especially the organs and other soft tissues) is vaporized and oxidized by the intense heat; gases released are discharged through the exhaust system.

Jewelry, such as necklaces, wrist-watches and rings, are ordinarily removed before cremation, and returned to the family. Several implanted devices are required to be removed. Pacemakers and other medical devices can cause large, dangerous explosions.

Contrary to popular belief, the cremated remains are not ashes in the usual sense. After the incineration is completed, the dry bone fragments are swept out of the retort and pulverised by a machine called a Cremulator—essentially a high-capacity, high-speed Pulverizer —to process them into "ashes" or "cremated remains", although pulverisation may also be performed by hand. This leaves the bone with a fine sand like texture and color, able to be scattered without need for mixing with any foreign matter, though the size of the grain varies depending on the Cremulator used. The mean weight of an adult's remains is 2.4 kg (5.3 lb); the mean weight for adult males is about 1 kg (2.2 lb) higher than that for adult females. There are various types of Cremulators, including rotating devices, grinders, and older models using heavy metal balls. The grinding process typically takes about 20 seconds.

In most Asian countries, the bones are not pulverised, unless requested beforehand. When not pulverised, the bones are collected by the family and stored as one might do with ashes.

The appearance of cremated remains after grinding is one of the reasons they are called ashes, although a non-technical term sometimes used is "cremains", a portmanteau of "cremated" and "remains". (The Cremation Association of North America prefers that the word "cremains" not be used for referring to "human cremated remains". The reason given is that "cremains" is thought to have less connection with the deceased, whereas a loved one's "cremated remains" has a more identifiable human connection.)

After final grinding, the ashes are placed in a container, which can be anything from a simple cardboard box to a decorative urn. The default container used by most crematoria, when nothing more expensive has been selected, is usually a hinged, snap-locking plastic box.

Ash weight and composition

Cremated remains are mostly dry calcium phosphates with some minor minerals, such as salts of sodium and potassium. Sulfur and most carbon are driven off as oxidized gases during the process, although about 1–4% of carbon remains as carbonate.

The ash remaining represents very roughly 3.5% of the body's original mass (2.5% in children). Because the weight of dry bone fragments is so closely connected to skeletal mass, their weight varies greatly from person to person. Because many changes in body composition (such as fat and muscle loss or gain) do not affect the weight of cremated remains, the weight of the remains can be more closely predicted from the person's height and sex (which predicts skeletal weight), than it can be predicted from the person's simple weight.

Ashes of adults can be said to weigh from 876 to 3,784 g (1 lb 15 oz to 8 lb 5 oz), with women's ashes generally weighing below 2,750 g (6 lb 1 oz) and men's ashes generally weighing above 1,887 g (4 lb 3 oz).

Bones are not all that remain after cremation. There may be melted metal lumps from missed jewellery; casket furniture; dental fillings; and surgical implants, such as hip replacements. Breast implants do not have to be removed before cremation. Some medical devices such as pacemakers may need to be removed before cremation to avoid the risk of explosion. Large items such as titanium hip replacements (which tarnish but do not melt) or casket hinges are usually removed before processing, as they may damage the processor. (If they are missed at first, they must ultimately be removed before processing is complete, as items such as titanium joint replacements are far too durable to be ground.) Implants may be returned to the family, but are more commonly sold as ferrous/non-ferrous scrap metal. After the remains are processed, smaller bits of metal such as tooth fillings, and rings (commonly known as gleanings) are sieved out and may be later interred in common, consecrated ground in a remote area of the cemetery. They may also be sold as precious metal scrap.

Retention or disposal of remains

Cremated remains are returned to the next of kin in different manners according to custom and country. In the United States, the cremated remains are almost always contained in a thick watertight polyethylene plastic bag contained within a hard snap-top rectangular plastic container, which is labeled with a printed paper label. The basic sealed plastic container bag may be contained within a further cardboard box or velvet sack, or they may be contained within an urn if the family had already purchased one. An official certificate of cremation prepared under the authority of the crematorium accompanies the remains, and if required by law, the permit for disposition of human remains, which must remain with the cremated remains.

Cremated remains can be kept in an urn, stored in a special memorial building (columbarium), buried in the ground at many locations or sprinkled on a special field, mountain, or in the sea. In addition, there are several services in which the cremated remains will be scattered in a variety of ways and locations. Some examples are via a helium balloon, through fireworks, shot from shotgun shells, by boat or scattered from an aeroplane or drone. One service sends a lipstick-tube sized sample of the cremated remains into low earth orbit, where they remain for years (but not permanently) before reentering the atmosphere. Some companies offer a service to turn part of the cremated remains into synthetic diamonds which can then be made into jewelry. This "cremation jewelry" is also known as funeral jewelry, remembrance jewelry or memorial jewelry. A portion of the cremated remains may be retained in a specially designed locket known as cremation jewelry, or even blown into special glass keepsakes and glass orbs

Cremated remains may also be incorporated, with urn and cement, into part of an artificial reef, or they can also be mixed into paint and made into a portrait of the deceased. Some individuals use a very small amount of the remains in tattoo ink, for remembrance portraits. Cremated remains can be scattered in national parks in the United States with a special permit. They can also be scattered on private property with the permission of the owner. The cremated remains may also be entombed. Most cemeteries will grant permission for burial of cremated remains in occupied cemetery plots that have already been purchased or are in use by the families disposing of the cremated remains without any additional charge or oversight.

Ashes are alkaline. In some areas such as Snowdon, Wales, environmental authorities have warned that the frequent scattering of ashes can change the nature of the soil, and may affect the ecology.

The final disposition depends on the personal preferences of the deceased as well as their cultural and religious beliefs. Some religions will permit the cremated remains to be sprinkled or retained at home. Some religions, such as Roman Catholicism, prefer to either bury or entomb the remains. Hinduism obliges the closest male relative (son, grandson, etc.) of the deceased to immerse the cremated remains in the holy river Ganges, preferably at one of the holy cities Triveni Sangam, Allahabad, Varanasi, or Haridwar in India. The Sikhs immerse the remains in the Sutlej, usually at Kiratpur Sahib. In southern India, the ashes are immersed in the river Kaveri at Paschima vahini in Srirangapattana at a stretch where the river flows from east to west, depicting the life of a human being from sunrise to sunset. In Japan and Taiwan, the remaining bone fragments are given to the family and are used in a burial ritual before final interment.

Reasons

Aside from religious reasons (discussed below), some people find they prefer cremation over traditional burial for personal reasons. The thought of a long and slow decomposition process is unappealing to some; many people find that they prefer cremation because it disposes of the body relatively quickly.

Other people view cremation as a way of simplifying their funeral process. These people view a traditional ground burial as an unneeded complication of their funeral process, and thus choose cremation to make their services as simple as possible. Cremation is a more simple disposition method to plan than a burial funeral. This is because with a burial funeral one would have to plan for more transportation services for the body as well as embalming and other body preservation methods. With a burial funeral one will also have to purchase a casket, headstone, grave plot, opening and closing of the grave fee, and mortician fees. Cremation funerals only require planning the transportation of the body to a crematorium, cremation of the body, and a cremation urn.

The cost factor tends to make cremation attractive. Generally speaking, cremation is cheaper than a traditional burial service, especially if direct cremation (also known as bare cremation) is chosen, in which the body is cremated as soon as legally possible without any sort of services. For some, even cremation is still relatively expensive, especially as a lot of fuel is required to perform it. Methods to reduce fuel consumption/fuel cost include the use of different fuels (i.e. natural gas or propane, compared to wood) and by using an incinerator (retort) (closed cabin) rather than an open fire.

For surviving kin, cremation is preferred because of simple portability. Survivors relocating to another city or country have the option of transporting the remains of their loved ones with the ultimate goal of being interred or scattered together.

Environmental impact

Despite being an obvious source of carbon emissions, cremation does have environmental advantages over burial, depending on local practice. Studies by Elisabeth Keijzer for the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Research found that cremation has less of an environmental impact than a traditional burial (the study did not address natural burials), while the newer method of alkaline hydrolysis (sometimes called green cremation or resomation) had less impact than both. The study was based on Dutch practice; American crematoria are more likely to emit mercury, but are less likely to burn hardwood coffins. Keijzer's studies also found that a cremation or burial accounts for only about a quarter of a funeral's environmental impact; the carbon emissions of people travelling to the funeral are far greater.

Each cremation requires about 110 L (28 US gal) of fuel and releases about 240 kg (540 lb) of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Thus, the roughly 1 million bodies that are cremated annually in the United States produce about 240,000 t (270,000 short tons) of carbon dioxide, which is more CO2 pollution than 22,000 average American homes generate in a year. The environmental impact may be reduced by using cremators for longer periods, and relaxing the requirement for a cremation to take place on the same day that the coffin is received, which reduces the use of fossil fuel and hence carbon emissions. Cremation is therefore becoming more friendly toward the environment. Some funeral and crematorium owners offer a carbon neutral funeral service incorporating efficient-burning coffins made from lightweight recycled composite board.

Burial is a known source of certain environmental contaminants, with the major ones being formaldehyde and the coffin itself. Cremation can also release contaminants, such as mercury from dental fillings. In some countries such as the United Kingdom, the law now requires that cremators be fitted with abatement equipment (filters) that remove serious pollutants such as mercury.

Another environmental concern is that traditional burial takes up a great deal of space. In a traditional burial, the body is buried in a casket made from a variety of materials. In the United States, the casket is often placed inside a concrete vault or liner before burial in the ground. While individually this may not take much room, combined with other burials, it can over time cause serious space concerns. Many cemeteries, particularly in Japan and Europe as well as those in larger cities, have run out of permanent space. In Tokyo, for example, traditional burial plots are extremely scarce and expensive, and in London, a space crisis led Harriet Harman to propose reopening old graves for "double-decker" burials. Some cities in Germany do not have plots for sale, only for lease. When the lease expires, the remains are disinterred and a specialist bundles the bones, inscribes the forehead of the skull with the information that was on the headstone, and places the remains in a special crypt. In Singapore, cremation is preferred by most Singaporeans because burial there is limited to 15 years.

Religious views

Christianity

Main article: Cremation in ChristianityIn Christian countries and cultures, cremation has historically been discouraged and viewed as a desecration of God's image, and as interference with the resurrection of the dead taught in Scripture. It is now acceptable to some denominations, since a literal interpretation of Scripture is less common in modern reformist traditions.

Catholicism

Christians preferred to bury the dead rather than to cremate the remains, as was common in Roman culture. The early church carried on Judaism's respect for the human body as being created in God's image, and followed their practices of speedy interment, in hopes of the future resurrection of all dead. The Roman catacombs and Medieval veneration of relics of Roman Catholic saints witness to this preference. For them, the body was not a mere receptacle for a spirit that was the real person, but an integral part of the human person. They looked on the body as sanctified by the sacraments and itself the temple of the Holy Spirit, and thus requiring to be disposed of in a way that honours and reveres it, and they saw many early practices involved with disposal of dead bodies as pagan in origin or an insult to the body.

The idea that cremation might interfere with God's ability to resurrect the body was refuted by the 2nd-century Octavius of Minucius Felix, in which he said: "Every body, whether it is dried up into dust, or is dissolved into moisture, or is compressed into ashes, or is attenuated into smoke, is withdrawn from us, but it is reserved for God in the custody of the elements. Nor, as you believe, do we fear any loss from sepulture, but we adopt the ancient and better custom of burying in the earth." A similar practice of boiling to remove flesh from bones was also punished with excommunication in a 1300 decree of Pope Boniface VIII. And while there was a clear and prevailing preference for burial, there was no general Church law forbidding cremation until 1866. In Medieval Europe, cremation was practiced mainly in situations where there were multitudes of corpses simultaneously present, such as after a battle, after a pestilence or famine, and where there was an imminent fear of diseases spreading from the corpses, since individual burials with digging graves would take too long and body decomposition would begin before all the corpses had been interred.

Beginning in the Middle Ages, and even more so in the 18th century and later, non-Christian rationalists and classicists began to advocate cremation again as a statement denying the resurrection and/or the afterlife, although the pro-cremation movement often took care to address these concerns. Sentiment within the Catholic Church against cremation became hardened in the face of the association of cremation with "professed enemies of God." When Masonic groups advocated cremation as a means of rejecting Christian belief in the resurrection, the Holy See forbade Catholics to practise cremation in 1886. The 1917 Code of Canon Law incorporated this ban. In 1963, recognizing that, in general, cremation was being sought for practical purposes and not as a denial of bodily resurrection, the choice of cremation was permitted in some circumstances. The current 1983 Code of Canon Law, states: "The Church earnestly recommends the pious custom of Christian burial be retained; but it does not entirely forbid cremation, except if this is chosen for reasons which are contrary to Christian teaching."

There are no universal rules governing Catholic funeral rites in connection with cremation, but episcopal conferences have laid down rules for various countries. Of these, perhaps the most elaborate are those established, with the necessary confirmation of the Holy See, by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and published as Appendix II of the United States edition of the Order of Christian Funerals.

Although the Holy See has in some cases authorized bishops to grant permission for funeral rites to be carried out in the presence of cremated remains, it is preferred that the rites be carried out in the presence of a still intact body. Practices that show insufficient respect for the ashes of the dead such as turning them into jewelry or scattering them are forbidden for Catholics, but burial on land or sea or enclosing in a niche or columbarium is now acceptable.

Anglicanism and Lutheranism

In 1917, Volume 6 of the American Lutheran Survey stated that "The Lutheran clergy as a rule refuse" and that "Episcopal pastors often take a stand against it." Indeed, in the 1870s, the Anglican Bishop of London stated that the practice of cremation would "undermine the faith of mankind in the doctrine of the resurrection of the body, hasten rejection of a Scriptural worldview and so bring about a most disastrous social revolution." In The Lutheran Pastor, George Henry Gerberding stated:

Third. As to cremation. This is not a Biblical or Christian mode of disposing of the dead. The Old and New Testament agree and take for granted that as the body was taken originally from the earth, so it is to return to the earth again. Burial is the natural and Christian mode. There is a beautiful symbolism in it. The whole terminology of eschatology presupposes it. Cremation is purely heathenish. It was the main practice among pagan Greeks and Romans. The majority of Hindus thus dispose of their dead. It is dishonoring to the body, intended as a temple of the Holy Ghost and to bear the image of God. It is an insidious denial of the doctrine of the resurrection.

Some Protestant churches welcomed the use of cremation at a much earlier date than the Catholic Church; pro-cremation sentiment was not unanimous among Protestants, as some have retained a literal interpretation of Scripture. The first crematoria in the Protestant countries were built in the 1870s, and in 1908, the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey—one of the most famous Anglican churches—required that remains be cremated for burial in the abbey's precincts. Today, "scattering", or "strewing," is an acceptable practice in some Protestant denominations, and some churches have their own "garden of remembrance" on their grounds in which remains can be scattered. Some denominations, like Lutheran churches in Scandinavia, favour the urns being buried in family graves. A family grave can thus contain urns of many generations and also the urns of spouses and loved ones.

Methodism

An 1898 Methodist tract titled Immortality and Resurrection noted that "burial is the result of a belief in the resurrection of the body, while cremation anticipates its annihilation." The Methodist Review noted in 1874 that "Three thoughts alone would lead us to suppose that the early Christians would have special care for their dead, namely, the essential Jewish origin of the Church; the mode of burial of their founder; and the doctrine of the resurrection of the body, so powerfully urged by the apostles, and so mighty in its influence on the primitive Christians. From these considerations, the Roman custom of cremation would be most repulsive to the Christian mind."

Since at least 1992, the United Methodist Church does not have a specific official statement that either endorses or condemns cremation, leaving the choice to individuals and families. Resources within the official ritual refer to the possible use of an urn and the interment of ashes.

Eastern Orthodox and other opposition

Some branches of Christianity entirely oppose cremation, including non-mainstream Protestant groups and the Orthodox churches. The Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches forbid cremation. Exceptions are made for circumstances where it cannot be avoided (when civil authority demands it, in aftermath of war or during epidemics) or if it may be sought for good cause, such as the discovery of body already in the state of decomposition. But when a cremation is specifically and willfully chosen for no good cause by the one who is deceased, he or she is not permitted a funeral in the church and may also be permanently excluded from burial in a Christian cemetery and liturgical prayers for the departed. In Orthodoxy, cremation is perceived as a rejection of the temple of God and of the dogma of the general resurrection.

Most independent Bible churches, free churches, Holiness churches and those of Anabaptist faiths will not practice cremation. As one example, the Church of God (Restoration) forbids the practice of cremation, believing as the Early Church did, that it continues to be a pagan practice.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) has, in past decades, discouraged cremation without expressly forbidding it. In the 1950s, for example, Apostle Bruce R. McConkie wrote that "only under the most extraordinary and unusual circumstances" would cremation be consistent with LDS teachings.

More recent LDS publications have provided instructions for how to dress the deceased when they have received their temple endowments (and thus wear temple garments) prior to cremation for those wishing to do so, or in countries where the law requires cremation. Except where required by law, the family of the deceased may decide whether the body should be cremated, though the Church "does not normally encourage cremation."

Hinduism

See also: Antyesti-

Burning ghats of Manikarnika, at Varanasi, India.

Burning ghats of Manikarnika, at Varanasi, India.

-

Cremation of Mahatma Gandhi at Rajghat, 31 January 1948. It was attended by Jawaharlal Nehru, Lord and Lady Mountbatten, Maulana Azad, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Sarojini Naidu and other national leaders. His son Devdas Gandhi lit the pyre.

Cremation of Mahatma Gandhi at Rajghat, 31 January 1948. It was attended by Jawaharlal Nehru, Lord and Lady Mountbatten, Maulana Azad, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Sarojini Naidu and other national leaders. His son Devdas Gandhi lit the pyre.

-

Cremation process at Pashupatinath temple.

Cremation process at Pashupatinath temple.

-

A Hindu cremation rite in Nepal. The samskara above shows the body wrapped in saffron red on a pyre.

A Hindu cremation rite in Nepal. The samskara above shows the body wrapped in saffron red on a pyre.

-

Cremation taking place at Pashupatinath Temple.

Indian religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism practice cremation. The founder of Buddhism, the Buddha, was cremated.

A dead adult Hindu is mourned with a cremation, while a dead child is typically buried. The rite of passage is performed in harmony with the Hindu religious view that the microcosm of all living beings is a reflection of a macrocosm of the universe. The soul (Atman, Brahman) is the essence and immortal that is released at the Antyesti ritual, but both the body and the universe are vehicles and transitory in various schools of Hinduism. They consist of five elements – air, water, fire, earth, and space. The last rite of passage returns the body to the five elements and origins. The roots of this belief are found in the Vedas, for example in the hymns of Rigveda in section 10.16, as follows:

Burn him not up, nor quite consume him, Agni: let not his body or his skin be scattered,

O all possessing Fire, when thou hast matured him, then send him on his way unto the Fathers.

When thou hast made him ready, all possessing Fire, then do thou give him over to the Fathers,

When he attains unto the life that waits him, he shall become subject to the will of gods.

The Sun receive thine eye, the Wind thy Prana (life-principle, breathe); go, as thy merit is, to earth or heaven.

Go, if it be thy lot, unto the waters; go, make thine home in plants with all thy members.

The final rite in the case of untimely death of a child is usually not cremation but a burial. This is rooted in Rigveda's section 10.18, where the hymns mourn the death of the child, praying to deity Mrityu to "neither harm our girls nor our boys", and pleads the earth to cover, protect the deceased child as a soft wool.

Ashes of the cremated bodies are usually spread in rivers, which are considered holy in the Hindu practice. The Ganges is considered to be the holiest river, and Varanasi, situated on the banks of the river, is regarded as the most sacred site for cremation.

Balinese

Balinese Hindu dead are generally buried inside the container for a period of time, which may exceed one month or more, so that the cremation ceremony (Ngaben) can occur on an auspicious day in the Balinese-Javanese Calendar system ("Saka"). Additionally, if the departed was a court servant, member of the court or minor noble, the cremation can be postponed up to several years to coincide with the cremation of their Prince. Balinese funerals are very expensive and the body may be interred until the family can afford it or until there is a group funeral planned by the village or family when costs will be less. The purpose of burying the corpse is for the decay process to consume the fluids of the corpse, which allows for an easier, more rapid and more complete cremation.

Islam

Main article: Islamic funeralMost Muslims believe Islam strictly forbids cremation. Its teaching is that cremation is not in line with the respect and dignity due to the deceased. They believe Islam has specific rites for the treatment of the body after death.

Judaism

The first reference to cremation in the Hebrew Bible is found in 1 Samuel 31. In this passage, the dead bodies of Saul and his sons are burned, and their bones are buried.

Judaism has traditionally disapproved of cremation in the past, as a rejection of the respect due to humans who are created in the image of God. Judaism has also disapproved of preservation of the dead by means of embalming and mummifying, as this involves mutilation and abuse of the corpse. Mummification was a practice of the ancient Egyptians, among whom the Israelites are said in the Torah to have lived as slaves.

Through history and up to the philosophical movements of the current era Modern Orthodox, Orthodox, Haredi, and Hasidic movements in Judaism have maintained the historical practice and strict Biblical line against cremation and disapprove of it, as Halakha (Jewish law) forbids it. This halakhic concern is grounded in the literal interpretation of Scripture, viewing the body as created in the image of God and upholding a bodily resurrection as core beliefs of traditional Judaism. This interpretation was occasionally opposed by some Jewish groups such as the Sadducees, who denied resurrection. The Tanakh emphasizes burial as the normal practice, for instance Devarim (Deuteronomy) 21:23 (specifically commanding the burial of executed criminals), with both a positive command derived from this verse to command one to bury a dead body and a negative command forbidding neglecting to bury a dead body. Some from the generally liberal Conservative Jewish also oppose cremation, some very strongly, seeing it as a rejection of God's design.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, as the Jewish cemeteries in many European towns had become crowded and were running out of space, in a few cases cremation for the first time became an approved means of corpse disposal among emerging liberal and Reform Jewish movements in line with their general rejection of literal scripture interpretation and traditional Torah ritual laws. Current liberal movements like Reform Judaism still permit cremation, although burial remains the preferred option. The Central Conference of American Rabbis has issued a responsa stating that families are permitted to choose cremation, but Reform rabbis are allowed to discourage the practice. However, Reform rabbis are instructed not to refuse to officiate at cremations.

In Israel religious ritual events including free burial and funeral services for all who die in Israel and all citizens including the majority Jewish population including for the secular or non-observant are almost universally facilitated through the Rabbinate of Israel. This is an Orthodox organization following historical and traditional Jewish law. In Israel there were no formal crematories until 2004 when B&L Cremation Systems Inc. became the first crematory manufacturer to sell a retort to Israel. In August 2007, an orthodox youth group in Israel was accused of burning down the country's sole crematorium, which they see as an affront to God. The crematorium was rebuilt by its owner and the retort replaced.

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith forbids cremation. A letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi to a National Spiritual Assembly states, "He feels that, in view of what 'Abdu'l-Bahá has said against cremation, the believers should be strongly urged, as an act of faith, to make provisions against their remains being cremated. Bahá'u'lláh has laid down as a law, in the Aqdas, the manner of Baháʼí burial, and it is so beautiful, befitting and dignified, that no believer should deprive himself of it."

Wicca

Both burial and cremation are practiced by Wiccans and there is no set directive on how the body should be disposed of after death. Wiccans believe that the body is merely a shell for the spirit so cremation is not viewed as irreverent or disrespectful. One tradition practiced by Wiccans is to mix the ashes from cremation with soil which is then used to plant a tree.

Zoroastrianism

Traditionally, Zoroastrianism disavows cremation or burial to preclude pollution of fire or earth. The traditional method of corpse disposal is through ritual exposure in a "Tower of Silence", but both burial and cremation are increasingly popular alternatives. Some contemporary adherents of the faith have opted for cremation. Parsi-Zoroastrian singer Freddie Mercury of the group Queen was cremated after his death.

Chinese

Neo-Confucianism under Zhu Xi strongly discourages cremation of one's parents' corpses as unfilial. Han Chinese traditionally practiced burial and viewed cremation as taboo and as a barbarian practice.

Traditionally, only Buddhist monks in China practiced cremation because ordinary Han Chinese detested cremation, refusing to do it. But now, the atheist Communist party enforces a strict cremation policy. Exceptions are made for Hui who do not cremate their dead due to Islamic beliefs.

The minority Jurchen and their Manchu descendants originally practiced cremation as part of their culture. They adopted the practice of burial from the Han, but many Manchus continued to cremate their dead.

Pets

In Japan, more than 465 companion animal temples are in operation. These venues hold funerals and rituals for dead pets. In Australia, pet owners can purchase services to have their companion animal cremated and placed in a pet cemetery or taken home.

The cost of pet cremation depends on location, where the cremation is done, and time of cremation. The American Humane Society's cost for the cremation of a pet weighing under 22.5 kg (50 lb) costs $110, while a pet weighing over 23 kg (51 lb) is $145. The cremated remains are available for the owner to pick up in seven to ten business days. Urns for the companion animal range from $50 to $150.

Though pet cremation has accelerated in recent years, Americans are still burying their pets by a 2:1 ratio.

Recent controversies

Tri-State Crematory incident

Main article: Tri-State Crematory scandalIn early 2002, 334 corpses that were supposed to have been cremated in the previous few years at the Tri-State Crematory were found intact and decaying on the crematorium's grounds in the U.S. state of Georgia, having been dumped there by the crematorium's proprietor. Many of the corpses were decayed beyond identification. Some families received "ashes" that were made of wood and concrete dust.

Operator Ray Brent Marsh had 787 criminal charges filed against him. On 19 November 2004, Marsh pleaded guilty to all charges. Marsh was sentenced to two 12-year prison sentences, one each from Georgia and Tennessee, to be served concurrently; he was also sentenced to probation for 75 years following his incarceration.

Civil suits were filed against the Marsh family and a number of funeral homes who shipped bodies to Tri-State; these suits were ultimately settled. The property of the Marsh family has been sold, but collection of the full $80-million judgment remains doubtful.

Rates

Main article: List of countries by cremation rateThe cremation rate varies considerably across countries with Japan reporting a 99.97% cremation rate while Romania reported a rate of 0.5% in 2018. The cremation rate in the United Kingdom has been increasing steadily with the national average rate rising from 34.70% in 1960 to 78.10% in 2019. According to the National Funeral Directors Association, the cremation rate in the United States in 2016 was 50.2% and this was in 2017 expected to increase to 63.8% by 2025 and 78.8% in 2035.

See also

- Antyesti

- Burial at sea

- Burial in space

- Cremation in Japan

- Death

- Promession

- Resomation

- Sati

- Self-immolation

- Tissue digestion

References

This article incorporates text from China revolutionized, by John Stuart Thomson, a publication from 1913, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from China revolutionized, by John Stuart Thomson, a publication from 1913, now in the public domain in the United States.

- Matthews Cremation Division (2006), Cremation Equipment Operator Training Program, p. 1

- Gillespie, R (1997) Burnt and unburnt carbon: dating charcoal and burnt bone from the Willandra Lakes, Australia: Radiocarbon 39, 225-236.

- Gillespie, R (1998) Alternative timescales: a critical review of Willandra Lakes dating. Archaeology in Oceania, 33, 169-182.

- Bowler, J.M. 1971. Pleistocene salinities and climatic change: Evidence from lakes and lunettes in southeastern Australia. In: Mulvaney, D.J. and Golson, J. (eds), Aboriginal Man and Environment in Australia. Canberra: Australian National University Press, pp. 47–65.

- "IMS-FORTH: About IMS". Ims.forth.gr. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Museum record 2007,3005.2 The British Museum, London

- ^ Laqueur, Thomas (30 October 2015). "The burning question – How cremation became our last act of self-determination". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- S.J. Plunkett, Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times (Tempus Publishing, Stroud 2005), 1–62.

- von Döllinger, Johann Joseph Ignaz (1841). A History of the Church. C. Dolman and T. Jomes. p. 9.

The punishment of death was inflicted on the refusal of baptism, on the heathen practice of burning the dead, and on the violation of the days of fasting

- Peach, Howard (2003). Curious Tales of Old North Yorkshire. Sigma Leisure. p. 99. ISBN 1-85058-793-0.

- Schmidt, Alvin J. (2004). How Christianity Changed the World. Zondervan. p. 261. ISBN 0-310-26449-9.

- Williams, Howard; Giles, Melanie (2016). Archaeologists and the Dead: Mortuary Archaeology in Contemporary Society. Oxford University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-19-875353-7.

- Neil R Storey (2013). The Little Book of Death. The History Press. ISBN 9780752492483.

- ^ "Typology: Crematorium". Architectural Review. 14 November 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- "USA." Encyclopedia of Cremation. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, 2005. Credo Reference. Web. 17 September 2012.

- Cobb, John Storer (1901). A Quartercentury of Cremation in North America. Knight and Millet. p. 150.

- ^ "History of Modern Cremation in Great Britain from 1874: The First Hundred Years". The Cremation Society of Great Britain. 1974. Introduction. Archived from the original on 3 August 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- Alon Confino; Paul Betts; Dirk Schumann (2013). Between Mass Death And Individual Loss: The Place of the Dead in Twentieth-Century Germany. Berghahn Books. p. 94. ISBN 9780857453846.

- Boi, Annalisa; Celsi, Valeria (2015). "The Crematorium Temple in the Monumental Cemetery in Milan". In_Bo. Ricerche e Progetti per Il Territorio. 6 (8). doi:10.6092/issn.2036-1602/6076.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Cremation by Lewis H. Mates (p. 21-23)

- ^ "Woking Crematorium". Internet. remembranceonline. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- Harris, Tim (16 September 2002). "Druid doc with a bee in his bonnet". theage.com.au. Melbourne. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- "Doctor William Price". Rhondda Cynon Taf Library Service. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- The History Channel. "26 March – This day in history". Archived from the original on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

- "The LeMoyne Crematory". Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "An Unceremonious Rite; Cremation of Mrs. Ben Pitman" (PDF). The New York Times. 16 February 1879. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- Sanburn, Josh. "The New American Way of Death." Time 181.24 (2013): 30. Academic Search Premier. Web. 16 September 2013.

- "Woking Crematorium". Internet. The Cremation Society of Great Britain. Archived from the original on 3 August 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- "Cremation". Catholic Encyclopedia. The Encyclopedia Press.

In conclusion, it must be remembered that there is nothing directly opposed to any dogma of the Church in the practice of cremation, and that, if ever the leaders of this sinister movement so far control the governments of the world as to make this custom universal, it would not be a lapse in the faith confided to her were she obliged to conform.

- Dutch, Vereniging voor Facultatieve Lijkverbranding

- Groenendijk, Paul; Vollaard, Piet (2006). Architectuurgids Nederland. 010 Publishers. p. 213. ISBN 90-6450-573-X.

- Berenbaum, Michael; Yisrael Gutman (1998). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Indiana University Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-253-20884-2.

- Holocaust Timeline: The Camps. Archived 8 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Holocaust Research Project, "The Vrba-Wetzler Report", part 2. Alternate source: Świebocki (1997), pp. 218, 220, 224; in his reproduction of the Vrba–Wetzler report, Świebocki presents the material without paragraph breaks.

- "Kori Company (Berlin)". The Gas Chamber at Sonnenstein. ARC. 2005. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- "Crematorium at Majdanek". Jewish Virtual Library.org. 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- Kohmescher, Matthew F. (1999). Catholicism Today: A Survey of Catholic Belief and Practice. Paulist Press. pp. 178–179. ISBN 0-8091-3873-5.

- Klassens, Mirjam; Groote, Peter (January 2012). "Designing a place for goodbye: The architecture of crematoria in the Netherlands". Final Places – via researchgate.net.

- Nešpor, Zdeněk R.; Nešporová, Olga (2011). "'Life Begins in the Heat of Love and Ends in the Heat of Fire': Four Views on the Development of Cremation in Czech Society". Soudobé dějiny. 18 (4): 563–602. doi:10.51134/sod.2011.042 – via researchgate.com.

- Barron, James (10 August 2017). "In a Move Away From Tradition, Cremations Increase". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- "How is a Body Cremated? – Cremation Resource".

- "Project Profile of re-provisioning of Diamond Hill Crematorium" (PDF). Environmental Protection Department, Hong Kong. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- "Proposed replacement of cremators at Fu Shan Crematorium, Shatin". Environmental Protection Department, Hong Kong. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ "This is exactly what happens to your body when it is cremated and how long it takes to burn". Cambridge News. 12 September 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Schacht, Charles A. (2004), Refractories Handbook, Marcel Dekker

- Carlson, Lisa (1997). Caring for the Dead. Upper Access, Inc. p. 78. ISBN 0-942679-21-0.

- "The Cremation Process Guide: What You Need To Know In 2017". Cremation Institute. 16 April 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "cremation process in the uk". 3 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Code of Cremation Practice". Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ Code of Cremation Practice Archived 9 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Doncaster: Cemeteries, Crematorium, retrieved 26 November 2009

- "Melting down hips and knees: The afterlife of implants". BBC News. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- "cremulator". 3 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Gesetz über das Leichen-, Bestattungs- und Friedhofswesen des Landes Schleswig-Holstein (Bestattungsgesetz – BestattG) vom 4. Februar 2005, §17 Abs. 4". Ministerium für Justiz, Gleichstellung und Integration. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- "Containers for Cremation – aCremation". Acremation.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ In the Netherlands these are removed by either the undertaker or the hospital where the person died.Green, Jennifer; Green, Michael (2006). Dealing With Death: Practices and Procedures. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. p. 112. ISBN 1-84310-381-8.

- "Cremulator" is a trademark of DWF Europe.

- "Pulveriser for Cremated Remains". 11 November 1986. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ Warren, M; Maples, W (1997). "The anthropometry of contemporary commercial cremation". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 42 (3): 417–423. doi:10.1520/JFS14141J. PMID 9144931.

- Davies, Douglas J.; Mates, Lewis H. (2005). "Cremulation". Encyclopedia of Cremation. Ashgate Publishing. p. 152. ISBN 0-7546-3773-5.

- Carlson 1997, p. 80.

- Sublette, Kathleen; Flagg, Martin (1992). Final Celebrations: A Guide for Personal and Family Funeral Planning. Pathfinder Publishing. pp. 52. ISBN 0-934793-43-3.

- "Cremation Association of North America – About CANA". 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- "Cremation & the Science of Memorial Diamonds". 14 February 2020.

- Ted Eisenberg and Joyce K. Eisenberg, The Scoop on Breasts: A Plastic Surgeon Busts the Myths, Incompra Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-9857249-3-1

- Roberts, Brian (10 August 2016). "Turning The Dead into Diamonds: Meet The Ghoul Jewelers of Switzerland". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "Planting With Cremains – Is There A Safe Way To Bury Ashes". www.gardeningknowhow.com. 30 October 2019. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- Clark, Rhodri (26 January 2006). "(Don't) scatter my ashes on Snowdon". Walesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Aiken, Lewis R. (2000). Dying, Death, and Bereavement. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p. 131. ISBN 0-8058-3504-0.

- Sublette & Flagg, p. 53

- "5 Reasons Why You Should Choose Cremation". Safe Passage Urns. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- "Average Cost of Cremation". National Funeral Directors Association. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

- Keijzer, Elisabeth (May 2017). "The environmental impact of activities after life: life cycle assessment of funerals" (PDF). International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. 22 (5): 715–730. Bibcode:2017IJLCA..22..715K. doi:10.1007/s11367-016-1183-9. S2CID 113516933. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "Dissolving the dead: Alkaline hydrolysis, a new alternative to". BBC News. 22 May 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Herzog, Katie (29 May 2016). "A different way to die: the story of a natural burial". Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Spongberg, Alison L.; Becks, Paul M. (January 2000). "Inorganic Soil Contamination from Cemetery Leachate". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 117 (1–4): 313–327. Bibcode:2000WASP..117..313S. doi:10.1023/A:1005186919370. S2CID 93957180.

- "Funeral Industry Case Study" (PDF). carbonneutral.com.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2014.

- Shimizu, Louise Picon; Maruyama, Meredith Enman; Tsurumaki, Nancy Smith (1998). Japan Health Handbook. Kodansha International. p. 335. ISBN 4-7700-2356-1.

Not only is cremation of the body and interment of the ashes in an urn a long-standing Buddhist practice, it is also a highly practical idea today, given the scarcity of burial space in crowded modern Japan.

- Furse, Raymond (2002). Japan: An Invitation. Tuttle Publishing. p. 73. ISBN 0-8048-3319-2.

and prices so high that a burial plot in Tokyo a mere 21 feet square could easily cost $150,000.

- Land, John (30 May 2006). "Double burials in UK cemeteries to solve space shortage". 24dash.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- ^ "International Cremation Statistics 2019". The Cremation Society of Great Britain. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- "Crypt Burial System". www.nea.gov.sg. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

The New Burial Policy, introduced in 1998 to address the issue of land scarcity, limits burial to 15 years. After this period, graves will be exhumed and the remains cremated or re-interred, depending on one's religious requirements.

- Gassmann, Günther; Larson, Duane H.; Oldenburg, Mark W. (4 April 2001). Historical Dictionary of Lutheranism. Scarecrow Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780810866201. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

Cremation was unheard of from the time Charlemagne outlawed it (784) until the 17th century. At that point, the practice was urged primarily by those opposed to the church, and for a long time cremation was forbidden by Roman Catholicism and practiced only reluctantly by a few Protestants who did not believe in the literal resurrection of the dead. Recently, these strictures have eased, less interpret Scripture literally and more and more churches have established columbaria or memorial gardens within their precincts for the reception of the ashes by the faithful.

- Robert Pasnau, in the introduction to his translation of Summa Theologiae, says that Aquinas is "...quite clear in rejecting the sort of substance dualism proposed by Plato which goes so far as to identify human beings with their souls alone, as if the body were a kind of clothing that we put on," and that Aquinas believed that "we are a composite of soul and body, that a soul all by itself would not be a human being." See Aquinas, St. Thomas (2002). Summa Theologiae 1a, 75–89. trans. Pasnau. Hackett Publishing. p. xvii. ISBN 0-87220-613-0.

- Davies & Mates, "Cremation, Death and Roman Catholicism", p. 107

- 1 Corinthians 6:19

- Prothero, Stephen (2002). Purified by Fire: A History of Cremation in America. University of California Press. pp. 73–74. ISBN 0-520-23688-2.

To the traditionalists, cremation originated among "heathens" and "pagans" and was therefore anti-Christian.

- The full text of Octavius is available online from ccel.org. See also Davies & Mates, p. 107-108.

- "Cremation". Catholic Encyclopedia. The Encyclopedia Press.

- Prothero, p. 74-75

- ^ Prothero, p. 74.

- ^ McNamara, Edward (2014). "Mixing Ashes of the Dead", EWTN.

- "Piam et constantem – Over de crematie – RKDocumenten.nl". Rkdocumenten.nl. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Code of Canon Law, canon 1176 §3 Archived 8 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine; cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2301.

- "LITURGICAL NORMS ON CREMATION". Ewtn.com. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "USCCB Committee on Divine Worship, "Cremation and the Order of Christian Funerals"". Usccb.org. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "Many Minds of Many Men". American Lutheran Survey. 6. Columbia: Lutheran Survey Publishing Company: 658. 12 September 1917.

- "Contemporary Sayings". Appleton's Journal of Literature, Science, and Art (276–301). New York: D. Appleton and Company. 1874.

- Gerberding, George Henry (1902). The Lutheran Pastor. Lutheran Publication Society. p. 363. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Prothero, p. 77.

- Davies & Mates, "Westminster Abbey", p. 423.

- Kelley, William (1898). The Methodist Review. Cincinnati: Methodist Book Concern. p. 986.

- Withrow, W.H. (1874). "Withrow on the Catacombs". The Methodist Review. 26, 34, 56: 599.

- "May we consider organ donation and cremation?". Ask The UMC-FAQs. United Merthodist Church. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- "Services of Death and Resurrection". The United Methodist Book of Worship. Nashville, Tennessee: United Methodist Publishing House. 1992. p. 141. ISBN 0-687-03572-4.

- Cloud, David. "CREMATION: What does God think?". Way of Life Literature. Archived from the original on 24 January 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- Mckemy, S. (n.d.). RESPECTING THE IMAGE OF GOD An Apology for Traditional Christian Burial (pp. 5–6). Retrieved July 7, 2024, from https://www.orthodoxroad.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Orthodox-Christian-Burial-McKemy.pdf

- Grabbe, Protopresbyter George. "Cremation". Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- "Cremation – A Pagan Practice – The Church of God : Official Website". Churchofgod.net. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- McConkie, Bruce R. Mormon Doctrine, A Compendium of the Gospel, 1958

- "Selected Church Policies and Guidelines: 21.3.2 Cremation". Handbook 2: Administering the Church. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- Cremation of Gandhi's body, JAMES MICHAELS, January 31, 1948

- ^ Carl Olson (2007), The Many Colors of Hinduism: A Thematic-historical Introduction, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 978-0813540689, pages 99–100

- J Fowler (1996), Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1898723608, pages 59–60

- ^ Terje Oestigaard, in The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial (Editors: Sarah Tarlow, Liv Nilsson Stut), Oxford University Press, ISBN, pages 497–501

- Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami (2001). Living With Siva: Hinduism's Contemporary Culture. Himalayan Academy. p. 750. ISBN 0-945497-98-9.

- Sanskrit: ऋग्वेद: सूक्तं १०.१६ Wikisource;

Sukta XVI – Rigveda, English Translation: HH Wilson (Translator), pages 39–40;

Wendy Doniger (1981), The Rig Veda, Penguin Classics, ISBN 978-0140449891, see chapter on Death - Sukta XVIII – Rigveda, English Translation: HH Wilson (Translator), pages 46–49 with footnotes;

Wendy Doniger (1981), The Rig Veda, Penguin Classics, ISBN 978-0140449891, see chapter on Death - Daar, A. S.; Khitamy, A. (9 January 2001). "Bioethics for clinicians: 21. Islamic bioethics. Case 1". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 164 (1): 60–63. PMC 80636. PMID 11202669.

Mutilation, and thus cremation, is strictly prohibited in Islam.

- "Cremation Services". Retrieved 9 February 2019.

In eastern religions such as Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism and Buddhism cremation is mandated, while in Islam it is strictly forbidden.

- "Cremation in Islam". Islamweb.net. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "Islamic Funeral Rites". Islam.about.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- "Cremation & Christianity: What the Bible Says About Cremation". 29 August 2022.

- Schulweis, Harold M. "SHAILOS & TSUVAS: QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS". Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2007.

Judaism is a tradition which affirms life. It has struggled from its inception against concentration on death and instead focuses on the celebration of God's gift of life.

- Bleich, J. David (2002). Judaism and Healing: Halakhic Perspectives. KTAV Publishing House. p. 219. ISBN 0-88125-741-9.

- Devarim (Deuteronomy) 21:23

-

Shapiro, Rabbi Morris M. (1986). Binder, Rabbi Robert (ed.). "Cremation in the Jewish Tradition". The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. Archived from the original on 28 May 2007.

The subsequent weight of opinion is against cremation and there is no convincing reason why we should deviate from the sacred established method of burial.

-

Rabow, Jerome A. A Guide to Jewish Mourning and Condolence. Valley Beth Shalom. Archived from the original on 22 April 2006. Retrieved 3 February 2006.

... cremation is un-questionably unacceptable to Conservative Judaism. The process of cremation would substitute an artificial and "instant" destruction for the natural process of decay and would have the disposition of the remains subject to manipulation by the survivors rather than submit to the universal processes of nature.

- Rothschild, Rabbi Walter. "Cremation". Archived from the original on 10 October 2006. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

e have no ideological conflict with the custom which is now popularly accepted by many as clean and appropriate to modern conditions.

- "100. Cremation from the Jewish Standpoint". Central Conference of American Rabbis. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- "'Arson' at Tel Aviv crematorium". BBC.co.uk. 23 August 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2007.

- he Research Department of the Universal House of Justice (2020) BAHÁ’Í BURIAL and Related Laws: Extracts from the Bahá'í Writings. Bahá’í Distribution Services. p.99 https://bahai-library.com/pdf/compilations/compilation_bahai_burial_laws.pdf

- Buckland, Raymond (2003). Wicca for Life: The Way of the Craft—From Birth to Summerland. New York. p. 224. ISBN 0806538651.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - MacMorgan, Kaatryn (2001). All One Wicca: A Study in the Universal Eclectic Tradition of Wicca (Revised ed.). San Jose, California: Writers Club Press. p. 113. ISBN 059520273X.

- Richard V. Weekes (1984). Muslim peoples: a world ethnographic survey, Volume 1. Greenwood Press. p. 334. ISBN 0-313-23392-6. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 264. ISBN 0804746842. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Chur-Hansen, Anna. "Cremation Services Upon The Death of a Companion Animal: Views Of Service Providers And Service Users." Society & Animals 19.3 (2011): 248–260. Academic Search Premier. Web. 16 September 2013.

- "Cremation Services." Animal Humane Society. N/D. Web. 11 October 2013.

- "FuneralFide Survey Reveals How Americans Are Coping With Pandemic Deaths". Funeral Fide. 28 March 2021.

- ^ "Crematory operator gets12 years in prison". Nbcnews.com. 1 February 2005. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Barron, James (10 August 2017). "In a Move Away From Tradition, Cremations Increase". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

External links

| Fire | |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Science | |

| Components | |

| Individual fires | |

| Crime | |

| People | |

| Culture | |

| Organizations | |

| Other | |

| |

| Prehistoric technology | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||