| Short-tailed chinchilla | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conservation status | |

Endangered (IUCN 3.1) | |

| CITES Appendix I (CITES) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Chinchillidae |

| Genus: | Chinchilla |

| Species: | C. chinchilla |

| Binomial name | |

| Chinchilla chinchilla (Lichtenstein, 1829) | |

| |

| Past range of Chinchilla chinchilla. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The short-tailed chinchilla (Chinchilla chinchilla) is a small rodent part of the Chinchillidae family and is classified as an endangered species by the IUCN. Originating in South America, the chinchilla is part of the genus Chinchilla, which is separated into two species: the long-tailed chinchilla and the short-tailed chinchilla. Although the short-tailed chinchilla used to be found in Chile, Argentina, Peru, and Bolivia, the geographical distribution of the species has since shifted. Today, the species remains extant in the Andes mountains of northern Chile, but small populations have been found in southern Bolivia.

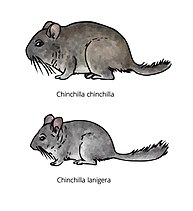

The short-tailed chinchilla is characterized by its grayish-blue fur which is extremely dense and plush. The short-tailed chinchilla has a short furry tail, which distinguishes it from the long-tailed chinchilla. Compared to C. lanigera, C. chinchilla has smaller, more rounded ears and is slightly smaller in body size.

Chinchillas have been exploited by humans for centuries. Commercial hunting of short-tailed chinchillas for fur began in 1828 in Chile, leading to an increased demand in Europe and the United States. As the demand for chinchilla pelts rose, the species number declined, leading to the species' apparent extinction in 1917. In 1929 a ban against hunting chinchillas was enacted, but not strictly enforced until 1983. Despite the species' rediscovery in the wild in 1953, the population of short-tailed chinchillas has continued to decline and has been categorized as endangered. Numerous threats to short-tailed chinchillas exist, including illegal hunting, habitat loss, firewood harvesting, and mining. In the last few decades, chinchillas have become increasingly popular as exotic pets, which has led to an increase in hunting and trapping.

Appearance and characteristics

Short-tailed chinchillas are generally smaller than long-tailed chinchillas and can be distinguished by comparing general body length, head size, tail length, and ear size. Upon closer observation, short-tailed chinchillas appear to have a larger body size, thicker necks, wider shoulders, and smaller ears than long-tailed chinchillas. Their tail length is what distinguishes them greatly, with short-tailed chinchillas having a tail measuring up to 100 mm, whereas long-tailed chinchillas have a tail measuring up to 130 mm. They have broad heads with vestigial cheek pouches.

The short-tailed chinchilla has a body size measuring between 23–38 cm long and weighing around 400-800g. Before maturity, short-tailed chinchillas weigh anywhere between 113-170g. Short-tailed chinchillas which have been bred to be pets are typically larger, measuring almost twice the size of those in the wild. In both wild and domestic short-tailed chinchillas, females are larger than males, but this difference in size is more apparent in domesticated chinchillas. Both sexes of short-tailed chinchillas are sexually dimorphic and appear the same, besides a size difference.

Short-tailed chinchillas are covered in a thick coat of extremely fine hair. The fur is very soft and plush due to the high number of hairs in a single follicle. 50 hairs can be held in a follicle, as compared to human hair which typically has one hair per follicle. Chinchilla fur is extremely valuable and is considered the softest in the world. Fur color can vary by individual, but colors range from violet, sapphire, blue-grey, beige, beige, brown, ebony, gray, white, cream, and pearl with each hair having a black tip. Typically, the underbelly of the species is a cream or off-white color shade.

The tail is usually bushy and has coarser hair. The dense coat of chinchillas allows the species to survive in the cold temperatures of their habitat in the Andes mountains. Since their coat is extremely thick, water is prevented from evaporating, which allows chinchillas to maintain body warmth. Additionally, the fur is so dense, that fleas and parasites cannot penetrate through the hair and will often die of suffocation. However, chinchillas cannot pant or sweat and with a dense fur coat, they are prone to overheating, especially in the care of humans. Their natural cooling mechanism is pumping blood through their ears, which have finer hair than the rest of their bodies.

Chinchillas are extremely well-adapted to their environment, with short front legs and long, powerful hind legs that aid in climbing and jumping in the mountains. Short-tailed chinchillas can jump across six-foot crevices and have large feet with foot pads and weak claws which allows them to move over rock crevices without slipping. Short-tailed chinchillas have extremely long vibrissae, in comparison to their body size, measuring around 100 mm. Short-tailed chinchillas have large eyes with vertical slit pupils, which allow them to have a clear, wide view at night. Another prominent feature are the large ears of chinchillas which helps them hear faint sounds and listen for predators.

Behavior

Although not much is known about short-tailed chinchilla behavior due to the shy nature of the species, they're known to be extremely intelligent creatures. In nature, they are timid and stay hidden throughout the day to avoid predators. Chinchillas are crepuscular, awakening at dawn and dusk to find food. They navigate and forage through the darkness using their vibrissae. At dawn, chinchillas sunbathe and groom themselves by taking dust baths. In the wild, chinchillas living in the Andes Mountains will roll in volcanic ash to coat their fur and prevent matting due to oils from their skin. Owners of pet chinchillas often provide them with dust or sand baths to help distribute oils, clear any dirt, and keep their fur soft.

Social interactions

Chinchillas are social creatures, normally living in colonies that may range from several to a hundred individuals, in groups called herds.

Reproduction

Short-tailed chinchillas have one mating partner and are considered monogamous. Due to females being slightly larger than males, female chinchillas often dominate males and will mate twice a year. The breeding season is November to May in the Northern Hemisphere. They have gestation periods lasting for 128 days.

Females may have up to two litters a year, but three is possible, but unusual. Litter size ranges from one to six offspring, called kits, with two being the average. Newborns chinchillas are capable of eating plant food and are weaned at 6 weeks old. Short-tailed chinchillas reach sexual maturity relatively quickly at an average age of 8 months, but it has been observed to occur at as young as 5.5 months with pet chinchillas or those in captivity. In the wild, short-tailed chinchillas typically have a lifespan of 8–10 years, as compared to in captivity, where they may survive for as long as 15–20 years.

An interesting behavior has been observed with females, with other lactating females sometimes feeding the young of others if they're unable to produce milk. Unlike many rodent species, father chinchillas also take on a caring and nurturing role, taking care of offspring when the mother is collecting food.

Defense mechanisms

Although they're not usually aggressive, pet chinchillas can develop a nipping tendency if handled improperly. If nipped or bitten by a predator, chinchillas can release tufts of hair, in order to escape. This leaves the predator with a mouth full of fur and is called a "fur slip.” A fur slip happens when a chinchilla releases tufts of its hair to escape its predator. With pet chinchillas, fur slip occurs while owners are holding their pets tightly or if the chinchilla is stressed.

Vocal sounds

In order to communicate, short-tailed chinchillas vocalize and have specific calls. There are ten distinct sounds emitted by chinchillas and each varies based on the context of the situation. Chinchillas will make a whistle-like sound, growl, or chatter their teeth to warn and alarm others of danger. Short-tailed chinchillas have also been known to emit hiss-and-spit noises if provoked and a cooing sound while mating.

Habitat

Short-tailed chinchillas primarily live in self-dug burrows or crevices of rocky areas with shrubs and grasses nearby, usually mountainous grasslands. Typically, their habitat has a sparse cover of thorny shrubs, cacti, and patches of succulents. Chinchillas live in arid climates at high altitudes with temperature dropping at night. Due to their environmental surroundings, chinchillas have adapted to expend less energy by having a low metabolic rate. Chinchillas are nocturnal creatures, often foraging for food at dusk and dawn.

Distribution

Historically, short-tailed chinchillas lived in the Andes mountains and were native to Peru, Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina. Although there has been speculation that chinchillas have become regionally extinct in Bolivia and Peru. In Bolivia, the chinchillas ranged from the La Paz, Oruro, and Potosi regions with the last wild specimens being captured by near Sabaya, and Caranga. However, a small population was recently discovered in Bolivia near the Laguna Colorada basin. Today, the only recorded sightings of short-tailed chinchillas has been in the Andes Mountains of northern Chile, where they remain endemic. In Chile, known chinchilla populations have been seen near the towns of El Laco, Morro Negro which are both near the Llullaillaco volcano in the Antofagasta region, as well as near the Nevado Tres Cruces National Park in the Atacama region.

Range

Their range extends through the relatively barren areas of the Andes Mountains at an elevation of 9,800 to over 16,000 feet (3,000 to 5,000 meters).

Diet

The diet for chinchillas is heavily plant-based, mainly grasses and shrubs found on the sides of mountains. Short-tailed chinchillas are herbivores and mainly feed on high-fiber vegetation specifically foliage, leaves, shrubs, seeds, nuts, grasses, herbs, flowers, and grains. Short-tailed chinchillas also compete with other species for food, mainly grazers like goats and cattle. Sometimes, they will feed on insects as part of their diet. However, their diet changes with the season, depending on what is available, mainly the perennial Chilean needle-grass. Short-tailed chinchillas acquire their drinking water through morning dew or from the flesh of various plants such as cacti. While eating, the short-tailed chinchilla sits upright and grasps its food in its front feet. Chinchillas are prone to overeating when an excess of food is available, so pet owners must be careful not to overfeed. Chinchillas also gnaw on whatever they can find to file down their constantly growing teeth.

History/Spread to U.S.

Chinchillas were hunted and kept as pets by the ancient Incas. In the 1700s, commercial hunting of chinchillas began in Chile. Short-tailed chinchillas were first brought to the U.S. in the 1920s by a mining engineer named Mathias F. Chapman. Chapman loved chinchillas and received permission from the government of Chile to import 12 individuals of the species to the U.S. He made sure to allow the chinchillas to assimilate into their new environment. Over the course of a year, he brought the chinchillas to a lower altitude and fed them food from their natural habitat.

Population threats

Predators

Chinchillas have natural predators in the wild, on the ground and in the sky. Birds, such as owls and hawks may swoop down and snatch chinchillas. On the ground, snakes, wild cats, and foxes hunt chinchillas as prey. In the three recognized populations, the Andean fox is the main predator. However, chinchillas are agile and can run up to 15 mph, so they can escape predators.

Habitat destruction

Short-tailed chinchillas are impacted by human activities such as mining and firewood extraction. Mining operations are a significant threat to chinchillas due to the destruction of their habitats. In Chile, gold fields have been discovered, but mining these areas would disrupt chinchilla populations. One main critical threat to chinchillas is the burning and harvesting of the algarrobilla shrub, which is their natural habitat. Since chinchillas are so well-adapted to their environments, any long-term environmental change threatens the species' survival. While hunting the species for their pelts, fur traders used dynamite to destroy their burrows and force the chinchillas out, which killed many in the process. The impact of these events has led to a 90% decrease in the short-tailed chinchilla population and caused them to go extinct in the three of the four countries where they were once found.

Fur trade

Many chinchillas are hunted for their fur and meat, often being bred for the pet and fur trade. Chinchilla fur is very fine and dense. One of their hair follicles can hold 50 hairs, while humans have 1 hair per follicle. Chinchilla fur is highly luxurious and in demand in the fur industry. Commercial hunting began in 1829 and increased every year by about half a million skins, as fur and skin demand increased in the United States and Europe: “he continuous and intense harvesting rate was not sustainable and the number of chinchillas hunted declined until the resource was considered economically extinct by 1917."

Once the hunting started, demand for the chinchilla skins skyrocketed in the United States and Europe, causing an unsustainable decline for living chinchillas. The supply of chinchillas slowly diminished, with the last short-tailed chinchilla being seen in 1953, causing skin prices to increase drastically. Short-tailed chinchillas were especially sought-after due to their higher quality fur and larger size as compared to long-tailed chinchillas.

Exotic pet trade

Since short-tailed chinchillas are so rare and their wild colonies only recently rediscovered, they are absent in the pet trade. Instead, their close relatives, long-tailed chinchillas are frequently kept as pets and often mistaken for their short-tailed cousins. Potential early-generation short-tailed and long-tailed chinchilla hybrids are considered absent from any wildlife trade for a long time, if not ever.

Conservation

The status of short-tailed chinchillas has declined by 90% over the years due to hunting and fur and trapping to support the fur trade. In the early 20th century, humans hunted chinchillas for their skins in great numbers which led to over 20 million individuals being killed. By the 1960s, both species of chinchilla, C.langiera and C.chinchilla were considered extinct in the wild. It wasn't until 1983, when specimens of short-tailed chinchillas were rediscovered.

Short-tailed chinchillas faced the greatest hunting during the early 1900s, since the South American fur traders were exchanging the chinchilla with Europeans. To meet the growing demand of chinchilla fur in Europe, the Andean fur traders had to hunt at great numbers. As the fur trade of chinchillas became increasingly successful, people began to quit their jobs as miners and farmers to become hunters.

Many inhumane hunting techniques were practiced to acquire the skins of chinchillas. These techniques ranged from using dogs to hunt to placing throned shrubs lit on fire into burrows. Others crushed chinchillas with large boulders. Throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, half a million chinchilla skins were being exported by Chile. However, due to these practices, only 1/3 of the exported skins were able to be purchased. Buenos Aires exported the majority of the skins, including the pelts coming from Bolivia. At this rate of exploitation, the short-tailed chinchilla became extinct in Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina.

To this day, only three populations are known. The short-tailed chinchillas are regionally extinct, except in Chile, but small groups have been rediscovered in Bolivia. Although, the short-tailed chinchillas is labeled as Critically Endangered in Bolivia. But, in Peru and Argentina, C.chinchilla is still labeled as Critically Endangered or Endangered instead of Extinct. In Chile, the species is Endangered. Chile has three regions where C.chinchilla can be found. In the Tarapacá region, they are considered “Extinguished,” and in the Antofagasta and Atacama regions “Endangered.”

Specific measures

In 1929, the first successful protection law prohibiting hunting chinchillas was passed in Chile, but weren't effectively enforced until the establishment in 1983 of the Reserva Nacional Las Chinchillas in Auco, Chile. Because of an impending extinction of short-tailed chinchillas, conservation measures were implemented in the 1890s in Chile. However, these measures were unregulated. The 1910 treaty between Chile, Bolivia and Peru brought the first international efforts to ban the hunting and commercial harvesting of chinchillas. Unfortunately, this effort led to great price increases, which caused a further decline of the remaining populations.

Today, short-tailed chinchillas are still considered Critically Endangered by the IUCN. Unfortunately, even with commercial hunting being illegal the last 100 years, C.chinchilla has not recovered or redistributed to their former areas of living. The populations that remain are small and isolated groups, which has caused reproductive isolation and led to inbreeding depression and low genetic diversity. This has caused a lower genetic fitness and further increased the species' risk of extinction. However, several individuals from a wild population were transferred to a breeding program in order to increase genetic diversity for captive populations.

Certain groups such "Save the Wild Chinchillas" help to raise awareness on the current status of the short-tailed chinchillas. In order to save the species, more research and surveys need to be done to find the location of other populations. If these actions are not taken, short-tailed chinchillas risk extinction within a matter of years.

Captivity

Short-tailed chinchillas in captivity are difficult to breed experimentally, which leads to high percentages of sterility. In captivity, there have been attempts to crossbreed long-tailed chinchillas and short-tailed chinchillas which have resulted in a few individuals.

References

- Roach, N.; Kennerley, R. (2016). "Chinchilla chinchilla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T4651A22191157. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- Domestic specimens of Chinchilla spp. are not subject to the provisions of CITES.

- ^ "Chinchilla | San Diego Zoo Animals & Plants". animals.sandiegozoo.org. Retrieved 2022-10-27.

- ^ Jiménez, Jaime E. (1996-07-01). "The extirpation and current status of wild chinchillas Chinchilla lanigera and C. brevicaudata". Biological Conservation. 77 (1): 1–6. Bibcode:1996BCons..77....1J. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(95)00116-6. ISSN 0006-3207.

- "Love My Chinchilla — Short Tailed vs. Long Tailed Chinchillas". lovemychinchilla.com. Retrieved 2022-11-26.

- ^ Newman, Shane (2019-03-28). "Short-tailed Chinchilla Facts, Habitat, Diet, Pictures". Animal Spot. Retrieved 2022-11-06.

- ^ Kopack, Holly. "Chinchilla chinchilla (short-tailed chinchilla)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2022-10-27.

- Valladares F, Pablo (2018). "Chinchilla chinchilla (Rodentia: Chinchillidae)". Mammalian Species. 50 (960): 51–58. doi:10.1093/mspecies/sey007. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- Jiménez, J. E.; Deane, A.; Pacheco, L. F.; Pavez, E. F.; Salazar-Bravo, J.; Valladares Faúndez, P. (2022-07-29). "Chinchilla conservation vs. gold mining in Chile". Science. 377 (6605): 480–481. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..480J. doi:10.1126/science.add7709. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 35901133. S2CID 251159194.

- Delgado, Eliseo; Pacheco, Luis Fernando; Salazar-Bravo, Jorge; Rocha, Omar (January 2018). "Rediscovery of the chinchilla in Bolivia". Oryx. 52 (1): 13–14. doi:10.1017/S003060531700179X. ISSN 0030-6053.

- ^ Valladares F, Pablo; Spotorno, Ángel E; Cortes M, Arturo; Zuleta R, Carlos (2018-08-20). "Chinchilla chinchilla (Rodentia: Chinchillidae)". Mammalian Species. 50 (960): 51–58. doi:10.1093/mspecies/sey007. ISSN 0076-3519.

- "Short-tailed Chinchilla". IUCN Red List.

| Extant species of family Chinchillidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chinchilla | |

| Lagidium (Mountain viscachas) | |

| Lagostomus | |

| Category | |

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Chinchilla chinchilla | |