In mathematics, a spiral is a curve which emanates from a point, moving further away as it revolves around the point. It is a subtype of whorled patterns, a broad group that also includes concentric objects.

Helices

Two major definitions of "spiral" in the American Heritage Dictionary are:

- a curve on a plane that winds around a fixed center point at a continuously increasing or decreasing distance from the point.

- a three-dimensional curve that turns around an axis at a constant or continuously varying distance while moving parallel to the axis; a helix.

The first definition describes a planar curve, that extends in both of the perpendicular directions within its plane; the groove on one side of a gramophone record closely approximates a plane spiral (and it is by the finite width and depth of the groove, but not by the wider spacing between than within tracks, that it falls short of being a perfect example); note that successive loops differ in diameter. In another example, the "center lines" of the arms of a spiral galaxy trace logarithmic spirals.

The second definition includes two kinds of 3-dimensional relatives of spirals:

- A conical or volute spring (including the spring used to hold and make contact with the negative terminals of AA or AAA batteries in a battery box), and the vortex that is created when water is draining in a sink is often described as a spiral, or as a conical helix.

- Quite explicitly, definition 2 also includes a cylindrical coil spring and a strand of DNA, both of which are fairly helical, so that "helix" is a more useful description than "spiral" for each of them. In general, "spiral" is seldom applied if successive "loops" of a curve have the same diameter.

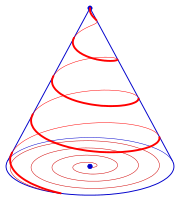

In the side picture, the black curve at the bottom is an Archimedean spiral, while the green curve is a helix. The curve shown in red is a conical spiral.

Two-dimensional

Main article: List of spirals

A two-dimensional, or plane, spiral may be easily described using polar coordinates, where the radius is a monotonic continuous function of angle :

The circle would be regarded as a degenerate case (the function not being strictly monotonic, but rather constant).

In --coordinates the curve has the parametric representation:

Examples

Some of the most important sorts of two-dimensional spirals include:

- The Archimedean spiral:

- The hyperbolic spiral:

- Fermat's spiral:

- The lituus:

- The logarithmic spiral:

- The Cornu spiral or clothoid

- The Fibonacci spiral and golden spiral

- The Spiral of Theodorus: an approximation of the Archimedean spiral composed of contiguous right triangles

- The involute of a circle

-

Archimedean spiral

Archimedean spiral

-

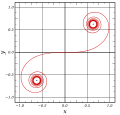

hyperbolic spiral

hyperbolic spiral

-

Fermat's spiral

Fermat's spiral

-

lituus

lituus

-

logarithmic spiral

logarithmic spiral

-

Cornu spiral

Cornu spiral

-

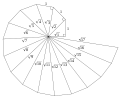

spiral of Theodorus

spiral of Theodorus

-

Fibonacci Spiral (golden spiral)

Fibonacci Spiral (golden spiral)

-

The involute of a circle (black) is not identical to the Archimedean spiral (red).

The involute of a circle (black) is not identical to the Archimedean spiral (red).

An Archimedean spiral is, for example, generated while coiling a carpet.

A hyperbolic spiral appears as image of a helix with a special central projection (see diagram). A hyperbolic spiral is some times called reciproke spiral, because it is the image of an Archimedean spiral with a circle-inversion (see below).

The name logarithmic spiral is due to the equation . Approximations of this are found in nature.

Spirals which do not fit into this scheme of the first 5 examples:

A Cornu spiral has two asymptotic points.

The spiral of Theodorus is a polygon.

The Fibonacci Spiral consists of a sequence of circle arcs.

The involute of a circle looks like an Archimedean, but is not: see Involute#Examples.

Geometric properties

The following considerations are dealing with spirals, which can be described by a polar equation , especially for the cases (Archimedean, hyperbolic, Fermat's, lituus spirals) and the logarithmic spiral .

- Polar slope angle

The angle between the spiral tangent and the corresponding polar circle (see diagram) is called angle of the polar slope and the polar slope.

From vector calculus in polar coordinates one gets the formula

Hence the slope of the spiral is

In case of an Archimedean spiral () the polar slope is

In a logarithmic spiral, is constant.

- Curvature

The curvature of a curve with polar equation is

For a spiral with one gets

In case of (Archimedean spiral)

.

Only for the spiral has an inflection point.

The curvature of a logarithmic spiral is

- Sector area

The area of a sector of a curve (see diagram) with polar equation is

For a spiral with equation one gets

The formula for a logarithmic spiral is

- Arc length

The length of an arc of a curve with polar equation is

For the spiral the length is

Not all these integrals can be solved by a suitable table. In case of a Fermat's spiral, the integral can be expressed by elliptic integrals only.

The arc length of a logarithmic spiral is

- Circle inversion

The inversion at the unit circle has in polar coordinates the simple description: .

- The image of a spiral under the inversion at the unit circle is the spiral with polar equation . For example: The inverse of an Archimedean spiral is a hyperbolic spiral.

- A logarithmic spiral is mapped onto the logarithmic spiral

Bounded spirals

(left),

(right)

The function of a spiral is usually strictly monotonic, continuous and unbounded. For the standard spirals is either a power function or an exponential function. If one chooses for a bounded function, the spiral is bounded, too. A suitable bounded function is the arctan function:

- Example 1

Setting and the choice gives a spiral, that starts at the origin (like an Archimedean spiral) and approaches the circle with radius (diagram, left).

- Example 2

For and one gets a spiral, that approaches the origin (like a hyperbolic spiral) and approaches the circle with radius (diagram, right).

Three-dimensional

"Space spiral" redirects here. For the building, see Space Spiral.Two well-known spiral space curves are conical spirals and spherical spirals, defined below. Another instance of space spirals is the toroidal spiral. A spiral wound around a helix, also known as double-twisted helix, represents objects such as coiled coil filaments.

Conical spirals

If in the --plane a spiral with parametric representation

is given, then there can be added a third coordinate , such that the now space curve lies on the cone with equation :

Spirals based on this procedure are called conical spirals.

- Example

Starting with an archimedean spiral one gets the conical spiral (see diagram)

Spherical spirals

Any cylindrical map projection can be used as the basis for a spherical spiral: draw a straight line on the map and find its inverse projection on the sphere, a kind of spherical curve.

One of the most basic families of spherical spirals is the Clelia curves, which project to straight lines on an equirectangular projection. These are curves for which longitude and colatitude are in a linear relationship, analogous to Archimedean spirals in the plane; under the azimuthal equidistant projection a Clelia curve projects to a planar Archimedean spiral.

If one represents a unit sphere by spherical coordinates

then setting the linear dependency for the angle coordinates gives a parametric curve in terms of parameter ,

Another family of spherical spirals is the rhumb lines or loxodromes, that project to straight lines on the Mercator projection. These are the trajectories traced by a ship traveling with constant bearing. Any loxodrome (except for the meridians and parallels) spirals infinitely around either pole, closer and closer each time, unlike a Clelia curve which maintains uniform spacing in colatitude. Under stereographic projection, a loxodrome projects to a logarithmic spiral in the plane.

In nature

The study of spirals in nature has a long history. Christopher Wren observed that many shells form a logarithmic spiral; Jan Swammerdam observed the common mathematical characteristics of a wide range of shells from Helix to Spirula; and Henry Nottidge Moseley described the mathematics of univalve shells. D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson's On Growth and Form gives extensive treatment to these spirals. He describes how shells are formed by rotating a closed curve around a fixed axis: the shape of the curve remains fixed, but its size grows in a geometric progression. In some shells, such as Nautilus and ammonites, the generating curve revolves in a plane perpendicular to the axis and the shell will form a planar discoid shape. In others it follows a skew path forming a helico-spiral pattern. Thompson also studied spirals occurring in horns, teeth, claws and plants.

A model for the pattern of florets in the head of a sunflower was proposed by H. Vogel. This has the form

where n is the index number of the floret and c is a constant scaling factor, and is a form of Fermat's spiral. The angle 137.5° is the golden angle which is related to the golden ratio and gives a close packing of florets.

Spirals in plants and animals are frequently described as whorls. This is also the name given to spiral shaped fingerprints.

-

An artist's rendering of a spiral galaxy.

An artist's rendering of a spiral galaxy.

-

Sunflower head displaying florets in spirals of 34 and 55 around the outside.

Sunflower head displaying florets in spirals of 34 and 55 around the outside.

As a symbol

A spiral like form has been found in Mezine, Ukraine, as part of a decorative object dated to 10,000 BCE. Spiral and triple spiral motifs served as Neolithic symbols in Europe (Megalithic Temples of Malta). The Celtic triple-spiral is in fact a pre-Celtic symbol. It is carved into the rock of a stone lozenge near the main entrance of the prehistoric Newgrange monument in County Meath, Ireland. Newgrange was built around 3200 BCE, predating the Celts; triple spirals were carved at least 2,500 years before the Celts reached Ireland, but have long since become part of Celtic culture. The triskelion symbol, consisting of three interlocked spirals or three bent human legs, appears in many early cultures: examples include Mycenaean vessels, coinage from Lycia, staters of Pamphylia (at Aspendos, 370–333 BC) and Pisidia, as well as the heraldic emblem on warriors' shields depicted on Greek pottery.

Spirals occur commonly in pre-Columbian art in Latin and Central America. The more than 1,400 petroglyphs (rock engravings) in Las Plazuelas, Guanajuato Mexico, dating 750-1200 AD, predominantly depict spirals, dot figures and scale models. In Colombia, monkeys, frog and lizard-like figures depicted in petroglyphs or as gold offering-figures frequently include spirals, for example on the palms of hands. In Lower Central America, spirals along with circles, wavy lines, crosses and points are universal petroglyph characters. Spirals also appear among the Nazca Lines in the coastal desert of Peru, dating from 200 BC to 500 AD. The geoglyphs number in the thousands and depict animals, plants and geometric motifs, including spirals.

Spiral shapes, including the swastika, triskele, etc., have often been interpreted as solar symbols. Roof tiles dating back to the Tang dynasty with this symbol have been found west of the ancient city of Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an).

Spirals are also a symbol of hypnosis, stemming from the cliché of people and cartoon characters being hypnotized by staring into a spinning spiral (one example being Kaa in Disney's The Jungle Book). They are also used as a symbol of dizziness, where the eyes of a cartoon character, especially in anime and manga, will turn into spirals to suggest that they are dizzy or dazed. The spiral is also found in structures as small as the double helix of DNA and as large as a galaxy. Due to this frequent natural occurrence, the spiral is the official symbol of the World Pantheist Movement. The spiral is also a symbol of the dialectic process and of Dialectical monism.

The spiral is a frequent symbol for spiritual purification, both within Christianity and beyond (one thinks of the spiral as the neo-Platonist symbol for prayer and contemplation, circling around a subject and ascending at the same time, and as a Buddhist symbol for the gradual process on the Path to Enlightenment). while a helix is repetitive, a spiral expands and thus epitomizes growth - conceptually ad infinitum.

-

Cucuteni Culture spirals on a bowl on stand, a vessel on stand, and an amphora, 4300-4000 BCE, ceramic, Palace of Culture, Iași, Romania

-

Neolithic spirals on the Newgrange entrance slab, unknown sculptor or architect, 3rd millennium BC

Neolithic spirals on the Newgrange entrance slab, unknown sculptor or architect, 3rd millennium BC

-

Mycenaean spirals on a burial stela, Grave Circle A, c.1550 BC, stone, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece

Mycenaean spirals on a burial stela, Grave Circle A, c.1550 BC, stone, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece

-

Meroitic spirals on a ram of the alley of the Amun Temple of Naqa, unknown sculptor, 1st century AD, stone, in situ

Meroitic spirals on a ram of the alley of the Amun Temple of Naqa, unknown sculptor, 1st century AD, stone, in situ

-

Islamic spiral design of the Great Mosque of Samarra, Samarra, Iraq, unknown architect, c. 851

Islamic spiral design of the Great Mosque of Samarra, Samarra, Iraq, unknown architect, c. 851

-

Gothic Revival spiralling bell-tower of the Maison des compagnons du tour de France, Nantes, unknown architect, c. 1910

Gothic Revival spiralling bell-tower of the Maison des compagnons du tour de France, Nantes, unknown architect, c. 1910

In art

The spiral has inspired artists throughout the ages. Among the most famous of spiral-inspired art is Robert Smithson's earthwork, "Spiral Jetty", at the Great Salt Lake in Utah. The spiral theme is also present in David Wood's Spiral Resonance Field at the Balloon Museum in Albuquerque, as well as in the critically acclaimed Nine Inch Nails 1994 concept album The Downward Spiral. The Spiral is also a prominent theme in the anime Gurren Lagann, where it represents a philosophy and way of life. It also central in Mario Merz and Andy Goldsworthy's work. The spiral is the central theme of the horror manga Uzumaki by Junji Ito, where a small coastal town is afflicted by a curse involving spirals. 2012 A Piece of Mind By Wayne A Beale also depicts a large spiral in this book of dreams and images. The coiled spiral is a central image in Australian artist Tanja Stark's Suburban Gothic iconography, that incorporates spiral electric stove top elements as symbols of domestic alchemy and spirituality.

See also

- Celtic maze (straight-line spiral)

- Concentric circles

- DNA

- Fibonacci number

- Hypogeum of Ħal-Saflieni

- Megalithic Temples of Malta

- Patterns in nature

- Seashell surface

- Spirangle

- Spiral vegetable slicer

- Spiral stairs

- Triskelion

References

- "Spiral | mathematics". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- "Spiral Definition (Illustrated Mathematics Dictionary)". www.mathsisfun.com. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- "spiral.htm". www.math.tamu.edu. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- "Math Patterns in Nature". The Franklin Institute. 2017-06-01. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- ^ "Spiral, American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Houghton Mifflin Company, Fourth Edition, 2009.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Archimedean Spiral". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Hyperbolic Spiral". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- von Seggern, D.H. (1994). Practical Handbook of Curve Design and Generation. Taylor & Francis. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-8493-8916-0. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- "Slinky -- from Wolfram MathWorld". Wolfram MathWorld. 2002-09-13. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- Ugajin, R.; Ishimoto, C.; Kuroki, Y.; Hirata, S.; Watanabe, S. (2001). "Statistical analysis of a multiply-twisted helix". Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications. 292 (1–4). Elsevier BV: 437–451. Bibcode:2001PhyA..292..437U. doi:10.1016/s0378-4371(00)00572-0. ISSN 0378-4371.

- Kuno Fladt: Analytische Geometrie spezieller Flächen und Raumkurven, Springer-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 3322853659, 9783322853653, S. 132

- Thompson, D'Arcy (1942) . On Growth and Form. Cambridge : University Press ; New York : Macmillan. pp. 748–933.

- Ben Sparks. "Geogebra: Sunflowers are Irrationally Pretty".

- Prusinkiewicz, Przemyslaw; Lindenmayer, Aristid (1990). The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants. Springer-Verlag. pp. 101–107. ISBN 978-0-387-97297-8.

- Anthony Murphy and Richard Moore, Island of the Setting Sun: In Search of Ireland's Ancient Astronomers, 2nd ed., Dublin: The Liffey Press, 2008, pp. 168-169

- "Newgrange Ireland - Megalithic Passage Tomb - World Heritage Site". Knowth.com. 2007-12-21. Archived from the original on 2013-07-26. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- For example, the trislele on Achilles' round shield on an Attic late sixth-century hydria at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, illustrated in John Boardman, Jasper Griffin and Oswyn Murray, Greece and the Hellenistic World (Oxford History of the Classical World) vol. I (1988), p. 50.

- "Rock Art Of Latin America & The Caribbean" (PDF). International Council on Monuments & Sites. June 2006. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- "Rock Art Of Latin America & The Caribbean" (PDF). International Council on Monuments & Sites. June 2006. p. 99. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- "Rock Art Of Latin America & The Caribbean" (PDF). International Council on Monuments & Sites. June 2006. p. 17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Jarus, Owen (14 August 2012). "Nazca Lines: Mysterious Geoglyphs in Peru". LiveScience. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Harrison, Paul. "Pantheist Art" (PDF). World Pantheist Movement. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Bruhn, Siglind (1997). "The Exchange of Natures and the Nature(s) of Time and Silence". Images and Ideas in Modern French Piano Music: The Extra-musical Subtext in Piano Works by Ravel, Debussy, and Messiaen. Aesthetics in music, ISSN 1062-404X, number 6. Stuyvesant, New York: Pendragon Press. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-945193-95-1. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- Israel, Nico (2015). Spirals : the whirled image in twentieth-century literature and art. New York Columbia University Press. pp. 161–186. ISBN 978-0-231-15302-7.

- 2012 A Piece of Mind By Wayne A Beale

- http://www.blurb.com/distribution?id=573100/#/project/573100/project-details/edit (subscription required)

- Stark, Tanja (4 July 2012). "Spiral Journeys : Turning and Returning". tanjastark.com.

- Stark, Tanja. "Lecture : Spiralling Undercurrents: Archetypal Symbols of Hurt, Hope and Healing". Jung Society Melbourne.

Related publications

- Cook, T., 1903. Spirals in nature and art. Nature 68 (1761), 296.

- Cook, T., 1979. The curves of life. Dover, New York.

- Habib, Z., Sakai, M., 2005. Spiral transition curves and their applications. Scientiae Mathematicae Japonicae 61 (2), 195 – 206.

- Dimulyo, Sarpono; Habib, Zulfiqar; Sakai, Manabu (2009). "Fair cubic transition between two circles with one circle inside or tangent to the other". Numerical Algorithms. 51 (4): 461–476. Bibcode:2009NuAlg..51..461D. doi:10.1007/s11075-008-9252-1. S2CID 22532724.

- Harary, G., Tal, A., 2011. The natural 3D spiral. Computer Graphics Forum 30 (2), 237 – 246 Archived 2015-11-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- Xu, L., Mould, D., 2009. Magnetic curves: curvature-controlled aesthetic curves using magnetic fields. In: Deussen, O., Hall, P. (Eds.), Computational Aesthetics in Graphics, Visualization, and Imaging. The Eurographics Association .

- Wang, Yulin; Zhao, Bingyan; Zhang, Luzou; Xu, Jiachuan; Wang, Kanchang; Wang, Shuchun (2004). "Designing fair curves using monotone curvature pieces". Computer Aided Geometric Design. 21 (5): 515–527. doi:10.1016/j.cagd.2004.04.001.

- Kurnosenko, A. (2010). "Applying inversion to construct planar, rational spirals that satisfy two-point G2 Hermite data". Computer Aided Geometric Design. 27 (3): 262–280. arXiv:0902.4834. doi:10.1016/j.cagd.2009.12.004. S2CID 14476206.

- A. Kurnosenko. Two-point G2 Hermite interpolation with spirals by inversion of hyperbola. Computer Aided Geometric Design, 27(6), 474–481, 2010.

- Miura, K.T., 2006. A general equation of aesthetic curves and its self-affinity. Computer-Aided Design and Applications 3 (1–4), 457–464 Archived 2013-06-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- Miura, K., Sone, J., Yamashita, A., Kaneko, T., 2005. Derivation of a general formula of aesthetic curves. In: 8th International Conference on Humans and Computers (HC2005). Aizu-Wakamutsu, Japan, pp. 166 – 171 Archived 2013-06-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- Meek, D.S.; Walton, D.J. (1989). "The use of Cornu spirals in drawing planar curves of controlled curvature". Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics. 25: 69–78. doi:10.1016/0377-0427(89)90076-9.

- Thomas, Sunil (2017). "Potassium sulfate forms a spiral structure when dissolved in solution". Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 11 (1): 195–198. Bibcode:2017RJPCB..11..195T. doi:10.1134/S1990793117010328. S2CID 99162341.

- Farin, Gerald (2006). "Class a Bézier curves". Computer Aided Geometric Design. 23 (7): 573–581. doi:10.1016/j.cagd.2006.03.004.

- Farouki, R.T., 1997. Pythagorean-hodograph quintic transition curves of monotone curvature. Computer-Aided Design 29 (9), 601–606.

- Yoshida, N., Saito, T., 2006. Interactive aesthetic curve segments. The Visual Computer 22 (9), 896–905 Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- Yoshida, N., Saito, T., 2007. Quasi-aesthetic curves in rational cubic Bézier forms. Computer-Aided Design and Applications 4 (9–10), 477–486 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine.

- Ziatdinov, R., Yoshida, N., Kim, T., 2012. Analytic parametric equations of log-aesthetic curves in terms of incomplete gamma functions. Computer Aided Geometric Design 29 (2), 129—140 .

- Ziatdinov, R., Yoshida, N., Kim, T., 2012. Fitting G2 multispiral transition curve joining two straight lines, Computer-Aided Design 44(6), 591—596 .

- Ziatdinov, R., 2012. Family of superspirals with completely monotonic curvature given in terms of Gauss hypergeometric function. Computer Aided Geometric Design 29(7): 510–518, 2012 .

- Ziatdinov, R., Miura K.T., 2012. On the Variety of Planar Spirals and Their Applications in Computer Aided Design. European Researcher 27(8–2), 1227—1232 .

External links

- Archived 2021-07-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Archimedes' spiral transforms into Galileo's spiral. Mikhail Gaichenkov, OEIS

| Spirals, curves and helices | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Curves |  | ||

| Helices |

| ||

| Spirals | |||

is a

is a  :

:

-

- -coordinates the curve has the parametric representation:

-coordinates the curve has the parametric representation:

. Approximations of this are found in nature.

. Approximations of this are found in nature.

, especially for the cases

, especially for the cases  (Archimedean, hyperbolic, Fermat's, lituus spirals) and the logarithmic spiral

(Archimedean, hyperbolic, Fermat's, lituus spirals) and the logarithmic spiral

the polar slope.

the polar slope.

is

is

) the polar slope is

) the polar slope is

is constant.

is constant.

of a curve with polar equation

of a curve with polar equation

one gets

one gets

.

. the spiral has an inflection point.

the spiral has an inflection point.

is

is

one gets

one gets

.

.

under the inversion at the unit circle is the spiral with polar equation

under the inversion at the unit circle is the spiral with polar equation  . For example: The inverse of an Archimedean spiral is a hyperbolic spiral.

. For example: The inverse of an Archimedean spiral is a hyperbolic spiral.

(left),

(left),  (right)

(right) of a spiral is usually strictly monotonic, continuous

and un

of a spiral is usually strictly monotonic, continuous

and un and the choice

and the choice  gives a spiral, that starts at the origin (like an Archimedean spiral) and approaches the circle with radius

gives a spiral, that starts at the origin (like an Archimedean spiral) and approaches the circle with radius  (diagram, left).

(diagram, left).

and

and  one gets a spiral, that approaches the origin (like a hyperbolic spiral) and approaches the circle with radius

one gets a spiral, that approaches the origin (like a hyperbolic spiral) and approaches the circle with radius  (diagram, right).

(diagram, right).

, such that the now space curve lies on the

, such that the now space curve lies on the  :

:

one gets the conical spiral (see diagram)

one gets the conical spiral (see diagram)

for the angle coordinates gives a

for the angle coordinates gives a  ,

,