The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's HMS Dreadnought, had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", and earlier battleships became known as pre-dreadnoughts. Her design had two revolutionary features: an "all-big-gun" armament scheme, with an unprecedented number of heavy-calibre guns, and steam turbine propulsion. As dreadnoughts became a crucial symbol of national power, the arrival of these new warships renewed the naval arms race between the United Kingdom and Germany. Dreadnought races sprang up around the world, including in South America, lasting up to the beginning of World War I. Successive designs increased rapidly in size and made use of improvements in armament, armour, and propulsion throughout the dreadnought era. Within five years, new battleships outclassed Dreadnought herself. These more powerful vessels were known as "super-dreadnoughts". Most of the original dreadnoughts were scrapped after the end of World War I under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty, but many of the newer super-dreadnoughts continued serving throughout World War II.

Dreadnought-building consumed vast resources in the early 20th century, but there was only one battle between large dreadnought fleets. At the Battle of Jutland in 1916, the British and German navies clashed with no decisive result. The term dreadnought gradually dropped from use after World War I, especially after the Washington Naval Treaty, as virtually all remaining battleships shared dreadnought characteristics; it can also be used to describe battlecruisers, the other type of ship resulting from the dreadnought revolution.

Origins

The distinctive all-big-gun armament of the dreadnought was developed in the first years of the 20th century as navies sought to increase the range and power of the armament of their battleships. The typical battleship of the 1890s, now known as the "pre-dreadnought", had a main armament of four heavy guns of 12-inch (300 mm) calibre, a secondary armament of six to eighteen quick-firing guns of between 4.7-and-7.5-inch (119 and 191 mm) calibre, and other smaller weapons. This was in keeping with the prevailing theory of naval combat that battles would initially be fought at some distance, but the ships would then approach to close range for the final blows (as they did in the Battle of Manila Bay), when the shorter-range, faster-firing guns would prove most useful. Some designs had an intermediate battery of 8-inch (203 mm) guns. Serious proposals for an all-big-gun armament were circulated in several countries by 1903.

All-big-gun designs commenced almost simultaneously in three navies. In 1904, the Imperial Japanese Navy authorized construction of Satsuma, originally designed with twelve 12-inch (305 mm) guns. Work began on her construction in May 1905. The Royal Navy began the design of HMS Dreadnought in January 1905, and she was laid down in October of the same year. Finally, the US Navy gained authorization for USS Michigan, carrying eight 12-inch guns, in March 1905, with construction commencing in December 1906.

The move to all-big-gun designs was accomplished because a uniform, heavy-calibre armament offered advantages in both firepower and fire control, and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 showed that future naval battles could, and likely would, be fought at long distances. The newest 12-inch (305 mm) guns had longer range and fired heavier shells than a gun of 10-or-9.2-inch (254 or 234 mm) calibre. Another possible advantage was fire control; at long ranges guns were aimed by observing the splashes caused by shells fired in salvoes, and it was difficult to interpret different splashes caused by different calibres of gun. There is still debate as to whether this feature was important.

Long-range gunnery

In naval battles of the 1890s the decisive weapon was the medium-calibre, typically 6-inch (152 mm), quick-firing gun firing at relatively short range; at the Battle of the Yalu River in 1894, the victorious Japanese did not commence firing until the range had closed to 4,300 yards (3,900 m), and most of the fighting occurred at 2,200 yards (2,000 m). At these ranges, lighter guns had good accuracy, and their high rate of fire delivered high volumes of ordnance on the target, known as the "hail of fire". Naval gunnery was too inaccurate to hit targets at a longer range.

By the early 20th century, British and American admirals expected future battleships would engage at longer distances. Newer models of torpedo had longer ranges. For instance, in 1903, the US Navy ordered a design of torpedo effective to 4,000 yards (3,700 m). Both British and American admirals concluded that they needed to engage the enemy at longer ranges. In 1900, Admiral Fisher, commanding the Royal Navy Mediterranean Fleet, ordered gunnery practice with 6-inch guns at 6,000 yards (5,500 m). By 1904 the US Naval War College was considering the effects on battleship tactics of torpedoes with a range of 7,000 to 8,000 yards (6,400 to 7,300 m).

The range of light and medium-calibre guns was limited, and accuracy declined badly at longer range. At longer ranges the advantage of a high rate of fire decreased; accurate shooting depended on spotting the shell-splashes of the previous salvo, which limited the optimum rate of fire.

On 10 August 1904 the Imperial Russian Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy had one of the longest-range gunnery duels to date—over 14,000 yd (13,000 m) during the Battle of the Yellow Sea. The Russian battleships were equipped with Lugeol range finders with an effective range of 4,400 yd (4,000 m), and the Japanese ships had Barr & Stroud range finders that reached out to 6,600 yd (6,000 m), but both sides still managed to hit each other with 12-inch (305 mm) fire at 14,000 yd (13,000 m). Naval architects and strategists around the world took notice.

All-big-gun mixed-calibre ships

An evolutionary step was to reduce the quick-firing secondary battery and substitute additional heavy guns, typically 9.2-to-10-inch (234 to 254 mm). Ships designed in this way have been described as 'all-big-gun mixed-calibre' or later 'semi-dreadnoughts'. Semi-dreadnought ships had many heavy secondary guns in wing turrets near the centre of the ship, instead of the small guns mounted in barbettes of earlier pre-dreadnought ships.

Semi-dreadnought classes included the British King Edward VII and Lord Nelson; Russian Andrei Pervozvanny; Japanese Katori, Satsuma, and Kawachi; American Connecticut and Mississippi; French Danton; Italian Regina Elena; and Austro-Hungarian Radetzky classes.

The design process for these ships often included discussion of an 'all-big-gun one-calibre' alternative. The June 1902 issue of Proceedings of the US Naval Institute contained comments by the US Navy's leading gunnery expert, P. R. Alger, proposing a main battery of eight 12-inch (305 mm) guns in twin turrets. In May 1902, the Bureau of Construction and Repair submitted a design for the battleship with twelve 10-inch (254 mm) guns in twin turrets, two at the ends and four in the wings. Lt. Cdr. Homer C. Poundstone submitted a paper to President Theodore Roosevelt in December 1902 arguing the case for larger battleships. In an appendix to his paper, Poundstone suggested a greater number of 11-and-9-inch (279 and 229 mm) guns was preferable to a smaller number of 12-and-9-inch (305 and 229 mm). The Naval War College and Bureau of Construction and Repair developed these ideas in studies between 1903 and 1905. War-game studies begun in July 1903 "showed that a battleship armed with twelve 11-or-12-inch (279 or 305 mm) guns hexagonally arranged would be equal to three or more of the conventional type."

The Royal Navy was thinking along similar lines. A design had been circulated in 1902–1903 for "a powerful 'all big-gun' armament of two calibres, viz. four 12-inch (305 mm) and twelve 9.2-inch (234 mm) guns." The Admiralty decided to build three more King Edward VIIs (with a mixture of 12-inch, 9.2-inch and 6-inch) in the 1903–1904 naval construction programme instead. The all-big-gun concept was revived for the 1904–1905 programme, the Lord Nelson class. Restrictions on length and beam meant the midships 9.2-inch turrets became single instead of twin, thus giving an armament of four 12-inch, ten 9.2-inch and no 6-inch. The constructor for this design, J. H. Narbeth, submitted an alternative drawing showing an armament of twelve 12-inch guns, but the Admiralty was not prepared to accept this. Part of the rationale for the decision to retain mixed-calibre guns was the need to begin the building of the ships quickly because of the tense situation produced by the Russo-Japanese War.

Switch to all-big-gun designs

The replacement of the 6-or-8-inch (152 or 203 mm) guns with weapons of 9.2-or-10-inch (234 or 254 mm) calibre improved the striking power of a battleship, particularly at longer ranges. Uniform heavy-gun armament offered many other advantages. One advantage was logistical simplicity. When the US was considering whether to have a mixed-calibre main armament for the South Carolina class, for example, William Sims and Poundstone stressed the advantages of homogeneity in terms of ammunition supply and the transfer of crews from the disengaged guns to replace gunners wounded in action.

A uniform calibre of gun also helped streamline fire control. The designers of Dreadnought preferred an all-big-gun design because it would mean only one set of calculations about adjustments to the range of the guns. Some historians today hold that a uniform calibre was particularly important because the risk of confusion between shell-splashes of 12-inch and lighter guns made accurate ranging difficult. This viewpoint is controversial, as fire control in 1905 was not advanced enough to use the salvo-firing technique where this confusion might be important, and confusion of shell-splashes does not seem to have been a concern of those working on all-big-gun designs. Nevertheless, the likelihood of engagements at longer ranges was important in deciding that the heaviest possible guns should become standard, hence 12-inch rather than 10-inch.

The newer designs of 12-inch gun mounting had a considerably higher rate of fire, removing the advantage previously enjoyed by smaller calibres. In 1895, a 12-inch gun might have fired one round every four minutes; by 1902, two rounds per minute was usual. In October 1903, the Italian naval architect Vittorio Cuniberti published a paper in Jane's Fighting Ships entitled "An Ideal Battleship for the British Navy", which called for a 17,000-ton ship carrying a main armament of twelve 12-inch guns, protected by armour 12 inches thick, and having a speed of 24 knots (28 mph; 44 km/h). Cuniberti's idea—which he had already proposed to his own navy, the Regia Marina—was to make use of the high rate of fire of new 12-inch guns to produce devastating rapid fire from heavy guns to replace the 'hail of fire' from lighter weapons. Something similar lay behind the Japanese move towards heavier guns; at Tsushima, Japanese shells contained a higher than normal proportion of high explosive, and were fused to explode on contact, starting fires rather than piercing armour. The increased rate of fire laid the foundations for future advances in fire control.

Building the first dreadnoughts

In Japan, the two battleships of the 1903–1904 programme were the first in the world to be laid down as all-big-gun ships, with eight 12-inch guns. The armour of their design was considered too thin, demanding a substantial redesign. The financial pressures of the Russo-Japanese War and the short supply of 12-inch guns—which had to be imported from the United Kingdom—meant these ships were completed with a mixture of 12-inch and 10-inch armament. The 1903–1904 design retained traditional triple-expansion steam engines, unlike Dreadnought.

The dreadnought breakthrough occurred in the United Kingdom in October 1905. Fisher, now the First Sea Lord, had long been an advocate of new technology in the Royal Navy and had recently been convinced of the idea of an all-big-gun battleship. Fisher is often credited as the creator of the dreadnought and the father of the United Kingdom's great dreadnought battleship fleet, an impression he himself did much to reinforce. It has been suggested Fisher's main focus was on the arguably even more revolutionary battlecruiser and not the battleship.

Shortly after taking office, Fisher set up a Committee on Designs to consider future battleships and armoured cruisers. The committee's first task was to consider a new battleship. The specification for the new ship was a 12-inch main battery and anti-torpedo-boat guns but no intermediate calibres, and a speed of 21 kn (24 mph; 39 km/h), which was two or three knots faster than existing battleships. The initial designs intended twelve 12-inch guns, though difficulties in positioning these guns led the chief constructor at one stage to propose a return to four 12-inch guns with sixteen or eighteen of 9.2-inch. After a full evaluation of reports of the action at Tsushima compiled by an official observer, Captain Pakenham, the Committee settled on a main battery of ten 12-inch guns, along with twenty-two 12-pounders as secondary armament. The committee also gave Dreadnought steam turbine propulsion, which was unprecedented in a large warship. The greater power and lighter weight of turbines meant the 21-knot design speed could be achieved in a smaller and less costly ship than if reciprocating engines had been used. Construction took place quickly; the keel was laid on 2 October 1905, the ship was launched on 10 February 1906, and completed on 3 October 1906—an impressive demonstration of British industrial might.

The first US dreadnoughts were the two South Carolina-class ships. Detailed plans for these were worked out in July–November 1905, and approved by the Board of Construction on 23 November 1905. Building was slow; specifications for bidders were issued on 21 March 1906, the contracts awarded on 21 July 1906 and the two ships were laid down in December 1906, after the completion of the Dreadnought.

Design

The designers of dreadnoughts sought to provide as much protection, speed, and firepower as possible in a ship of a realistic size and cost. The hallmark of dreadnought battleships was an "all-big-gun" armament, but they also had heavy armour concentrated mainly in a thick belt at the waterline and in one or more armoured decks. Secondary armament, fire control, command equipment, and protection against torpedoes also had to be crammed into the hull.

The inevitable consequence of demands for ever greater speed, striking power, and endurance meant that displacement, and hence cost, of dreadnoughts tended to increase. The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 imposed a limit of 35,000 tons on the displacement of capital ships. In subsequent years treaty battleships were commissioned to build up to this limit. Japan's decision to leave the Treaty in the 1930s, and the arrival of the Second World War, eventually made this limit irrelevant.

Armament

Dreadnoughts mounted a uniform main battery of heavy-calibre guns; the number, size, and arrangement differed between designs. Dreadnought mounted ten 12-inch guns. 12-inch guns had been standard for most navies in the pre-dreadnought era, and this continued in the first generation of dreadnought battleships. The Imperial German Navy was an exception, continuing to use 11-inch guns in its first class of dreadnoughts, the Nassau class.

Dreadnoughts also carried lighter weapons. Many early dreadnoughts carried a secondary armament of very light guns designed to fend off enemy torpedo boats. The calibre and weight of secondary armament tended to increase, as the range of torpedoes and the staying power of the torpedo boats and destroyers expected to carry them also increased. From the end of World War I onwards, battleships had to be equipped with many light guns as anti-aircraft armament.

Dreadnoughts frequently carried torpedo tubes themselves. In theory, a line of battleships so equipped could unleash a devastating volley of torpedoes on an enemy line steaming a parallel course. This was also a carry-over from the older tactical doctrine of continuously closing range with the enemy, and the idea that gunfire alone may be sufficient to cripple a battleship, but not sink it outright, so a coup de grace would be made with torpedoes. In practice, torpedoes fired from battleships scored very few hits, and there was a risk that a stored torpedo would cause a dangerous explosion if hit by enemy fire. And in fact, the only documented instance of one battleship successfully torpedoing another came during the action of 27 May 1941, where the British battleship HMS Rodney claimed to have torpedoed the crippled Bismarck at close range.

Position of main armament

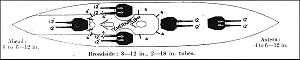

The effectiveness of the guns depended in part on the layout of the turrets. Dreadnought, and the British ships which immediately followed it, carried five turrets: one forward, one aft and one amidships on the centreline of the ship, and two in the 'wings' next to the superstructure. This allowed three turrets to fire ahead and four on the broadside. The Nassau and Helgoland classes of German dreadnoughts adopted a 'hexagonal' layout, with one turret each fore and aft and four wing turrets; this meant more guns were mounted in total, but the same number could fire ahead or broadside as with Dreadnought.

Dreadnought designs experimented with different layouts. The British Neptune-class battleship staggered the wing turrets, so all ten guns could fire on the broadside, a feature also used by the German Kaiser class. This risked blast damage to parts of the ship over which the guns fired, and put great stress on the ship's frames.

If all turrets were on the centreline of the vessel, stresses on the ship's frames were relatively low. This layout meant the entire main battery could fire on the broadside, though fewer could fire end-on. It meant the hull would be longer, which posed some challenges for the designers; a longer ship needed to devote more weight to armour to get equivalent protection, and the magazines which served each turret interfered with the distribution of boilers and engines. For these reasons, HMS Agincourt, which carried a record fourteen 12-inch guns in seven centreline turrets, was not considered a success.

A superfiring layout was eventually adopted as standard. This involved raising one or two turrets so they could fire over a turret immediately forward or astern of them. The US Navy adopted this feature with their first dreadnoughts in 1906, but others were slower to do so. As with other layouts there were drawbacks. Initially, there were concerns about the impact of the blast of the raised guns on the lower turret. Raised turrets raised the centre of gravity of the ship, and might reduce the stability of the ship. Nevertheless, this layout made the best of the firepower available from a fixed number of guns, and was eventually adopted generally. The US Navy used superfiring on the South Carolina class, and the layout was adopted in the Royal Navy with the Orion class of 1910. By World War II, superfiring was entirely standard.

Initially, all dreadnoughts had two guns to a turret. One solution to the problem of turret layout was to put three or even four guns in each turret. Fewer turrets meant the ship could be shorter, or could devote more space to machinery. On the other hand, it meant that in the event of an enemy shell destroying one turret, a higher proportion of the main armament would be out of action. The risk of the blast waves from each gun barrel interfering with others in the same turret reduced the rate of fire from the guns somewhat. The first nation to adopt the triple turret was Italy, in the Dante Alighieri, soon followed by Russia with the Gangut class, the Austro-Hungarian Tegetthoff class, and the US Nevada class. British Royal Navy battleships did not adopt triple turrets until after the First World War, with the Nelson class, and Japanese battleships not until the late-1930s Yamato class. Several later designs used quadruple turrets, including the British King George V class and French Richelieu class.

Main armament power and calibre

Rather than try to fit more guns onto a ship, it was possible to increase the power of each gun. This could be done by increasing either the calibre of the weapon and hence the weight of shell, or by lengthening the barrel to increase muzzle velocity. Either of these offered the chance to increase range and armour penetration.

Both methods offered advantages and disadvantages, though in general greater muzzle velocity meant increased barrel wear. As guns fire, their barrels wear out, losing accuracy and eventually requiring replacement. At times, this became problematic; the US Navy seriously considered stopping practice firing of heavy guns in 1910 because of the wear on the barrels. The disadvantages of guns of larger calibre are that guns and turrets must be heavier; and heavier shells, which are fired at lower velocities, require turret designs that allow a larger angle of elevation for the same range. Heavier shells have the advantage of being slowed less by air resistance, retaining more penetrating power at longer ranges.

Different navies approached the issue of calibre in different ways. The German navy, for instance, generally used a lighter calibre than the equivalent British ships, e.g. 12-inch calibre when the British standard was 13.5-inch (343 mm). Because German metallurgy was superior, the German 12-inch gun had better shell weight and muzzle velocity than the British 12-inch; and German ships could afford more armour for the same vessel weight because the German 12-inch guns were lighter than the 13.5-inch guns the British required for comparable effect.

Over time the calibre of guns tended to increase. In the Royal Navy, the Orion class, launched 1910, had ten 13.5-inch guns, all on the centreline; the Queen Elizabeth class, launched in 1913, had eight 15-inch (381 mm) guns. In all navies, fewer guns of larger calibre came to be used. The smaller number of guns simplified their distribution, and centreline turrets became the norm.

A further step change was planned for battleships designed and laid down at the end of World War I. The Japanese Nagato-class battleships in 1917 carried 410-millimetre (16.1 in) guns, which was quickly matched by the US Navy's Colorado class. Both the United Kingdom and Japan were planning battleships with 18-inch (457 mm) armament, in the British case the N3 class. The Washington Naval Treaty concluded on 6 February 1922 and ratified later limited battleship guns to not more than 16-inch (410 mm) calibre, and these heavier guns were not produced.

The only battleships to break the limit were the Japanese Yamato class, begun in 1937 (after the treaty expired), which carried 18 in (460 mm) main guns. By the middle of World War II, the United Kingdom was making use of 15 in (380 mm) guns kept as spares for the Queen Elizabeth class to arm the last British battleship, HMS Vanguard.

Some World War II-era designs were drawn up proposing another move towards gigantic armament. The German H-43 and H-44 designs proposed 20-inch (508 mm) guns, and there is evidence Hitler wanted calibres as high as 24-inch (609 mm); the Japanese 'Super Yamato' design also called for 20-inch guns. None of these proposals went further than very preliminary design work.

Secondary armament

The first dreadnoughts tended to have a very light secondary armament intended to protect them from torpedo boats. Dreadnought carried 12-pounder guns; each of her twenty-two 12-pounders could fire at least 15 rounds a minute at any torpedo boat making an attack. The South Carolinas and other early American dreadnoughts were similarly equipped. At this stage, torpedo boats were expected to attack separately from any fleet actions. Therefore, there was no need to armour the secondary gun armament, or to protect the crews from the blast effects of the main guns. In this context, the light guns tended to be mounted in unarmoured positions high on the ship to minimize weight and maximize field of fire.

Within a few years, the principal threat was from the destroyer—larger, more heavily armed, and harder to destroy than the torpedo boat. Since the risk from destroyers was very serious, it was considered that one shell from a battleship's secondary armament should sink (rather than merely damage) any attacking destroyer. Destroyers, in contrast to torpedo boats, were expected to attack as part of a general fleet engagement, so it was necessary for the secondary armament to be protected against shell splinters from heavy guns, and the blast of the main armament. This philosophy of secondary armament was adopted by the German navy from the start; Nassau, for instance, carried twelve 5.9 in (150 mm) and sixteen 3.5 in (88 mm) guns, and subsequent German dreadnought classes followed this lead. These heavier guns tended to be mounted in armoured barbettes or casemates on the main deck. The Royal Navy increased its secondary armament from 12-pounder to first 4-inch (100 mm) and then 6-inch (150 mm) guns, which were standard at the start of World War I; the US standardized on 5-inch calibre for the war but planned 6-inch guns for the ships designed just afterwards.

The secondary battery served several other roles. It was hoped that a medium-calibre shell might be able to score a hit on an enemy dreadnought's sensitive fire control systems. It was also felt that the secondary armament could play an important role in driving off enemy cruisers from attacking a crippled battleship.

The secondary armament of dreadnoughts was, on the whole, unsatisfactory. A hit from a light gun could not be relied on to stop a destroyer. Heavier guns could not be relied on to hit a destroyer, as experience at the Battle of Jutland showed. The casemate mountings of heavier guns proved problematic; being low in the hull, they proved liable to flooding, and on several classes, some were removed and plated over. The only sure way to protect a dreadnought from destroyer or torpedo boat attack was to provide a destroyer squadron as an escort. After World War I the secondary armament tended to be mounted in turrets on the upper deck and around the superstructure. This allowed a wide field of fire and good protection without the negative points of casemates. Increasingly through the 1920s and 1930s, the secondary guns were seen as a major part of the anti-aircraft battery, with high-angle, dual-purpose guns increasingly adopted.

Armour

Much of the displacement of a dreadnought was taken up by the steel plating of the armour. Designers spent much time and effort to provide the best possible protection for their ships against the various weapons with which they would be faced. Only so much weight could be devoted to protection, without compromising speed, firepower or seakeeping.

Central citadel

The bulk of a dreadnought's armour was concentrated around the "armoured citadel". This was a box, with four armoured walls and an armoured roof, around the most important parts of the ship. The sides of the citadel were the "armoured belt" of the ship, which started on the hull just in front of the forward turret and ran to just behind the aft turret. The ends of the citadel were two armoured bulkheads, fore and aft, which stretched between the ends of the armour belt. The "roof" of the citadel was an armoured deck. Within the citadel were the boilers, engines, and the magazines for the main armament. A hit to any of these systems could cripple or destroy the ship. The "floor" of the box was the bottom of the ship's hull, and was unarmoured, although it was, in fact, a "triple bottom".

The earliest dreadnoughts were intended to take part in a pitched battle against other battleships at ranges of up to 10,000 yd (9,100 m). In such an encounter, shells would fly on a relatively flat trajectory, and a shell would have to hit at or just about the waterline to damage the vitals of the ship. For this reason, the early dreadnoughts' armour was concentrated in a thick belt around the waterline; this was 11 inches (280 mm) thick in Dreadnought. Behind this belt were arranged the ship's coal bunkers, to further protect the engineering spaces. In an engagement of this sort, there was also a lesser threat of indirect damage to the vital parts of the ship. A shell which struck above the belt armour and exploded could send fragments flying in all directions. These fragments were dangerous but could be stopped by much thinner armour than what would be necessary to stop an unexploded armour-piercing shell. To protect the innards of the ship from fragments of shells which detonated on the superstructure, much thinner steel armour was applied to the decks of the ship.

The thickest protection was reserved for the central citadel in all battleships. Some navies extended a thinner armoured belt and armoured deck to cover the ends of the ship, or extended a thinner armoured belt up the outside of the hull. This "tapered" armour was used by the major European navies—the United Kingdom, Germany, and France. This arrangement gave some armour to a larger part of the ship; for the first dreadnoughts, when high-explosive shellfire was still considered a significant threat, this was useful. It tended to result in the main belt being very short, only protecting a thin strip above the waterline; some navies found that when their dreadnoughts were heavily laden, the armoured belt was entirely submerged. The alternative was an "all or nothing" protection scheme, developed by the US Navy. The armour belt was tall and thick, but no side protection at all was provided to the ends of the ship or the upper decks. The armoured deck was also thickened. The "all-or-nothing" system provided more effective protection against the very-long-range engagements of dreadnought fleets and was adopted outside the US Navy after World War I.

The design of the dreadnought changed to meet new challenges. For example, armour schemes were changed to reflect the greater risk of plunging shells from long-range gunfire, and the increasing threat from armour-piercing bombs dropped by aircraft. Later designs carried a greater thickness of steel on the armoured deck; Yamato carried a 16-inch (410 mm) main belt, but a deck 9-inch (230 mm) thick.

Underwater protection and subdivision

The final element of the protection scheme of the first dreadnoughts was the subdivision of the ship below the waterline into several watertight compartments. If the hull were holed—by shellfire, mine, torpedo, or collision—then, in theory, only one area would flood and the ship could survive. To make this precaution even more effective, many dreadnoughts had no doors between different underwater sections, so that even a surprise hole below the waterline need not sink the ship. There were still several instances where flooding spread between underwater compartments.

The greatest evolution in dreadnought protection came with the development of the anti-torpedo bulge and torpedo belt, both attempts to protect against underwater damage by mines and torpedoes. The purpose of underwater protection was to absorb the force of a detonating mine or torpedo well away from the final watertight hull. This meant an inner bulkhead along the side of the hull, which was generally lightly armoured to capture splinters, separated from the outer hull by one or more compartments. The compartments in between were either left empty, or filled with coal, water or fuel oil.

Propulsion

Dreadnoughts were propelled by two to four screw propellers. Dreadnought herself, and all British dreadnoughts, had screw shafts driven by steam turbines. The first generation of dreadnoughts built in other nations used the slower triple-expansion steam engine which had been standard in pre-dreadnoughts.

Turbines offered more power than reciprocating engines for the same volume of machinery. This, along with a guarantee on the new machinery from the inventor, Charles Parsons, persuaded the Royal Navy to use turbines in Dreadnought. It is often said that turbines had the additional benefits of being cleaner and more reliable than reciprocating engines. By 1905, new designs of reciprocating engine were available which were cleaner and more reliable than previous models.

Turbines also had disadvantages. At cruising speeds much slower than maximum speed, turbines were markedly less fuel-efficient than reciprocating engines. This was particularly important for navies which required a long range at cruising speeds—and hence for the US Navy, which was planning in the event of war to cruise across the Pacific and engage the Japanese in the Philippines.

The US Navy experimented with turbine engines from 1908 in the North Dakota, but was not fully committed to turbines until the Pennsylvania class in 1916. In the preceding Nevada class, one ship, USS Oklahoma, received reciprocating engines, while USS Nevada received geared turbines. The two New York-class battleships of 1914 both received reciprocating engines, but all four ships of the Florida (1911) and Wyoming (1912) classes received turbines.

The disadvantages of the turbine were eventually overcome. The solution which eventually was generally adopted was the geared turbine, where gearing reduced the rotation rate of the propellers and hence increased efficiency. This solution required technical precision in the gears and hence was difficult to implement.

One alternative was the turbo-electric drive where the steam turbine generated electrical power which then drove the propellers. This was particularly favoured by the US Navy, which used it for all dreadnoughts from late 1915–1922. The advantages of this method were its low cost, the opportunity for very close underwater compartmentalization, and good astern performance. The disadvantages were that the machinery was heavy and vulnerable to battle damage, particularly the effects of flooding on the electrics.

Turbines were never replaced in battleship design. Diesel engines were eventually considered by some powers, as they offered very good endurance and an engineering space taking up less of the length of the ship. They were also heavier, however, took up a greater vertical space, offered less power, and were considered unreliable.

Fuel

The first generation of dreadnoughts used coal to fire the boilers which fed steam to the turbines. Coal had been in use since the first steam warships. One advantage of coal was that it is quite inert (in lump form) and thus could be used as part of the ship's protection scheme. Coal also had many disadvantages. It was labour-intensive to pack coal into the ship's bunkers and then feed it into the boilers. The boilers became clogged with ash. Airborne coal dust and related vapours were highly explosive, possibly evidenced by the explosion of USS Maine. Burning coal as fuel also produced thick black smoke which gave away the position of a fleet and interfered with visibility, signaling, and fire control. In addition, coal was very bulky and had comparatively low thermal efficiency.

Oil-fired propulsion had many advantages for naval architects and officers at sea alike. It reduced smoke, making ships less visible. It could be fed into boilers automatically, rather than needing a complement of stokers to do it by hand. Oil has roughly twice the thermal content of coal. This meant that the boilers themselves could be smaller; and for the same volume of fuel, an oil-fired ship would have much greater range.

These benefits meant that, as early as 1901, Fisher was pressing the advantages of oil fuel. There were technical problems with oil-firing, connected with the different distribution of the weight of oil fuel compared to coal, and the problems of pumping viscous oil. The main problem with using oil for the battle fleet was that, with the exception of the United States, every major navy would have to import its oil. As a result, some navies adopted 'dual-firing' boilers which could use coal sprayed with oil; British ships so equipped, which included dreadnoughts, could even use oil alone at up to 60% power.

The US had large reserves of oil, and the US Navy was the first to wholeheartedly adopt oil-firing, deciding to do so in 1910 and ordering oil-fired boilers for the Nevada class, in 1911. The United Kingdom was not far behind, deciding in 1912 to use oil on its own in the Queen Elizabeth class; shorter British design and building times meant that Queen Elizabeth was commissioned before either of the Nevada-class vessels. The United Kingdom planned to revert to mixed firing with the subsequent Revenge class, at the cost of some speed—but Fisher, who returned to office in 1914, insisted that all the boilers should be oil-fired. Other major navies retained mixed coal-and-oil firing until the end of World War I.

Dreadnought building

Dreadnoughts developed as a move in an international battleship arms-race which had begun in the 1890s. The British Royal Navy had a big lead in the number of pre-dreadnought battleships, but a lead of only one dreadnought in 1906. This has led to criticism that the British, by launching HMS Dreadnought, threw away a strategic advantage. Most of the United Kingdom's naval rivals had already contemplated or even built warships that featured a uniform battery of heavy guns. Both the Japanese Navy and the US Navy ordered "all-big-gun" ships in 1904–1905, with Satsuma and South Carolina, respectively. Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II had advocated a fast warship armed only with heavy guns since the 1890s. By securing a head start in dreadnought construction, the United Kingdom ensured its dominance of the seas continued.

The battleship race soon accelerated once more, placing a great burden on the finances of the governments which engaged in it. The first dreadnoughts were not much more expensive than the last pre-dreadnoughts, but the cost per ship continued to grow thereafter. Modern battleships were the crucial element of naval power in spite of their price. Each battleship signalled national power and prestige, in a manner similar to the nuclear weapons of today. Germany, France, Russia, Italy, Japan and Austria-Hungary all began dreadnought programmes, and second-rank powers—including the Ottoman Empire, Greece, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile—commissioned British, French, German, and American yards to build dreadnoughts for them.

Anglo-German arms race

See also: World War I naval arms race and Causes of World War I

The construction of Dreadnought coincided with increasing tension between the United Kingdom and Germany. Germany had begun building a large battlefleet in the 1890s, as part of a deliberate policy to challenge British naval supremacy. With the signing of the Entente Cordiale in April 1904, it became increasingly clear the United Kingdom's principal naval enemy would be Germany, which was building up a large, modern fleet under the "Tirpitz" laws. This rivalry gave rise to the two largest dreadnought fleets of the pre-1914 period.

The first German response to Dreadnought was the Nassau class, laid down in 1907, followed by the Helgoland class in 1909. Together with two battlecruisers—a type for which the Germans had less admiration than Fisher, but which could be built under the authorization for armoured cruisers, rather than for capital ships—these classes gave Germany a total of ten modern capital ships built or building in 1909. The British ships were faster and more powerful than their German equivalents, but a 12:10 ratio fell far short of the 2:1 superiority the Royal Navy wanted to maintain.

In 1909, the British Parliament authorized an additional four capital ships, holding out hope Germany would be willing to negotiate a treaty limiting battleship numbers. If no such solution could be found, an additional four ships would be laid down in 1910. Even this compromise meant, when taken together with some social reforms, raising taxes enough to prompt a constitutional crisis in the United Kingdom in 1909–1910. In 1910, the British eight-ship construction plan went ahead, including four Orion-class super-dreadnoughts, augmented by battlecruisers purchased by Australia and New Zealand. In the same period, Germany laid down only three ships, giving the United Kingdom a superiority of 22 ships to 13. The British resolve, as demonstrated by their construction programme, led the Germans to seek a negotiated end to the arms race. The Admiralty's new target of a 60% lead over Germany was near enough to Tirpitz's goal of cutting the British lead to 50%, but talks foundered on the question on whether to include British colonial battlecruisers in the count, as well as on non-naval matters like the German demands for recognition of ownership of Alsace-Lorraine.

The dreadnought race stepped up in 1910 and 1911, with Germany laying down four capital ships each year and the United Kingdom five. Tension came to a head following the German Naval Law of 1912. This proposed a fleet of 33 German battleships and battlecruisers, outnumbering the Royal Navy in home waters. To make matters worse for the United Kingdom, the Imperial Austro-Hungarian Navy was building four dreadnoughts, while Italy had four and was building two more. Against such threats, the Royal Navy could no longer guarantee vital British interests. The United Kingdom was faced with a choice between building more battleships, withdrawing from the Mediterranean, or seeking an alliance with France. Further naval construction was unacceptably expensive at a time when social welfare provision was making calls on the budget. Withdrawing from the Mediterranean would mean a huge loss of influence, weakening British diplomacy in the region and shaking the stability of the British Empire. The only acceptable option, and the one recommended by First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, was to break with the policies of the past and to make an arrangement with France. The French would assume responsibility for checking Italy and Austria-Hungary in the Mediterranean, while the British would protect the north coast of France. In spite of some opposition from British politicians, the Royal Navy organised itself on this basis in 1912.

In spite of these important strategic consequences, the 1912 Naval Law had little bearing on the battleship-force ratios. The United Kingdom responded by laying down ten new super-dreadnoughts in its 1912 and 1913 budgets—ships of the Queen Elizabeth and Revenge classes, which introduced a further step-change in armament, speed and protection—while Germany laid down only five, concentrating resources on its army.

United States

The American South Carolina-class battleships were the first all-big-gun ships completed by one of the United Kingdom's rivals. The planning for the type had begun before Dreadnought was launched. There is some speculation that informal contacts with sympathetic Royal Navy officials influenced the US Navy design, but the American ship was very different.

The US Congress authorized the Navy to build two battleships, but of only 16,000 tons or lower displacement. As a result, the South Carolina class were built to much tighter limits than Dreadnought. To make the best use of the weight available for armament, all eight 12-inch guns were mounted along the centreline, in superfiring pairs fore and aft. This arrangement gave a broadside equal to Dreadnought, but with fewer guns; this was the most efficient distribution of weapons and proved a precursor of the standard practice of future generations of battleships. The principal economy of displacement compared to Dreadnought was in propulsion; South Carolina retained triple-expansion steam engines, and could manage only 18.5 kn (34.3 km/h) compared to 21 kn (39 km/h) for Dreadnought. For this reason the later Delaware class were described by some as the US Navy's first dreadnoughts; only a few years after their commissioning, the South Carolina class could not operate tactically with the newer dreadnoughts due to their low speed, and were forced to operate with the older pre-dreadnoughts.

The two 10-gun, 20,500-ton ships of the Delaware class were the first US battleships to match the speed of British dreadnoughts, but their secondary battery was "wet" (suffering from spray) and their bow was low in the water. An alternative 12-gun 24,000-ton design had many disadvantages as well; the extra two guns and a lower casemate had "hidden costs"—the two wing turrets planned would weaken the upper deck, be almost impossible to adequately protect against underwater attack, and force magazines to be located too close to the sides of the ship.

The US Navy continued to expand its battlefleet, laying down two ships in most subsequent years until 1920. The US continued to use reciprocating engines as an alternative to turbines until Nevada, laid down in 1912. In part, this reflected a cautious approach to battleship-building, and in part a preference for long endurance over high maximum speed owing to the US Navy's need to operate in the Pacific Ocean.

Japan

With their victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, the Japanese became concerned about the potential for conflict with the US. The theorist Satō Tetsutarō developed the doctrine that Japan should have a battlefleet at least 70% the size of that of the US. This would enable the Japanese navy to win two decisive battles: the first early in a prospective war against the US Pacific Fleet, and the second against the US Atlantic Fleet which would inevitably be dispatched as reinforcements.

Japan's first priorities were to refit the pre-dreadnoughts captured from Russia and to complete Satsuma and Aki. The Satsumas were designed before Dreadnought, but financial shortages resulting from the Russo-Japanese War delayed completion and resulted in their carrying a mixed armament, so they were known as "semi-dreadnoughts". These were followed by a modified Aki-type: Kawachi and Settsu of the Kawachi-class. These two ships were laid down in 1909 and completed in 1912. They were armed with twelve 12-inch guns, but they were of two different models with differing barrel-lengths, meaning that they would have had difficulty controlling their fire at long ranges.

In other countries

See also: South American dreadnought race

Compared to the other major naval powers, France was slow to start building dreadnoughts, instead finishing the planned Danton class of pre-dreadnoughts, laying down five in 1907 and 1908. In September 1910 the first of the Courbet class was laid down, making France the eleventh nation to enter the dreadnought race. In the Navy Estimates of 1911, Paul Bénazet asserted that from 1896 to 1911, France dropped from being the world's second-largest naval power to fourth; he attributed this to problems in maintenance routines and neglect. The closer alliance with the United Kingdom made these reduced forces more than adequate for French needs.

The Italian Regia Marina had received proposals for an all-big-gun battleship from Cuniberti well before Dreadnought was launched, but it took until 1909 for Italy to lay down one of its own. The construction of Dante Alighieri was prompted by rumours of Austro-Hungarian dreadnought-building. A further five dreadnoughts of the Conte di Cavour and Andrea Doria classes followed as Italy sought to maintain its lead over Austria-Hungary. These ships remained the core of Italian naval strength until World War II. The subsequent Francesco Caracciolo-class battleship were suspended (and later cancelled) on the outbreak of World War I.

In January 1909 Austro-Hungarian admirals circulated a document calling for a fleet of four dreadnoughts. A constitutional crisis in 1909–1910 meant no construction could be approved. In spite of this, shipyards laid down two dreadnoughts on a speculative basis—due especially to the energetic manipulations of Rudolf Montecuccoli, Chief of the Austro-Hungarian Navy—later approved along with an additional two. The resulting ships, all Tegetthoff class, were to be accompanied by a further four ships of the Ersatz Monarch class, but these were cancelled on the Austro-Hungarian entry into World War I.

In June 1909 the Imperial Russian Navy began construction of four Gangut dreadnoughts for the Baltic Fleet, and in October 1911, three more Imperatritsa Mariya-class dreadnoughts for the Black Sea Fleet were laid down. Of seven ships, only one was completed within four years of being laid down, and the Gangut ships were "obsolescent and outclassed" upon commissioning. Taking lessons from Tsushima, and influenced by Cuniberti, they ended up more closely resembling slower versions of Fisher's battlecruisers than Dreadnought, and they proved badly flawed due to their smaller guns and thinner armour when compared with contemporary dreadnoughts.

Spain commissioned three ships of the España class, with the first laid down in 1909. The three ships, the smallest dreadnoughts ever constructed, were built in Spain with British assistance; construction on the third ship, Jaime I, took nine years from its laying down date to completion because of non-delivery of critical material, especially armament, from the United Kingdom.

Brazil was the third country to begin construction on a dreadnought. It ordered three dreadnoughts from the United Kingdom which would mount a heavier main battery than any other battleship afloat at the time (twelve 12-inch/45 calibre guns). Two were completed for Brazil: Minas Geraes was laid down on by Armstrong (Elswick) on 17 April 1907, and its sister, São Paulo, followed thirteen days later at Vickers (Barrow). Although many naval journals in Europe and the US speculated that Brazil was really acting as a proxy for one of the naval powers and would hand the ships over to them as soon as they were complete, both ships were commissioned into the Brazilian Navy in 1910. The third ship, Rio de Janeiro, was nearly complete when rubber prices collapsed and Brazil could not afford her. She was sold to the Ottoman Empire in 1913.

The Netherlands intended by 1912 to replace its fleet of pre-dreadnought armoured ships with a modern fleet composed of dreadnoughts. After a Royal Commission proposed the purchase of nine dreadnoughts in August 1913, there were extensive debates over the need for such ships and—if they were necessary—over the actual number needed. These lasted into August 1914, when a bill authorizing funding for four dreadnoughts was finalized, but the outbreak of World War I halted the ambitious plan.

The Ottoman Empire ordered two dreadnoughts from British yards, Reshadiye in 1911 and Fatih Sultan Mehmed in 1914. Reshadiye was completed, and in 1913, the Ottoman Empire also acquired a nearly-completed dreadnought from Brazil, which became Sultan Osman I. At the start of World War I, Britain seized the two completed ships for the Royal Navy. Reshadiye and Sultan Osman I became HMS Erin and Agincourt respectively. (Fatih Sultan Mehmed was scrapped.) This greatly offended the Ottoman Empire. When two German warships, the battlecruiser SMS Goeben and the cruiser SMS Breslau, became trapped in Ottoman territory after the start of the war, Germany "gave" them to the Ottomans. (They remained German-crewed and under German orders.) The British seizure and the German gift proved important factors in the Ottoman Empire joining the Central Powers in October 1914.

Greece had ordered the dreadnought Salamis from Germany, but work stopped on the outbreak of war. The main armament for the Greek ship had been ordered in the United States, and the guns consequently equipped a class of British monitors. In 1914 Greece purchased two pre-dreadnoughts from the United States Navy, renaming them Kilkis and Lemnos in Royal Hellenic Navy service.

The Conservative Party-dominated House of Commons of Canada passed a bill purchasing three British dreadnoughts for $35 million to use in the Canadian Naval Service, but the measure was defeated in the Liberal Party-dominated Senate of Canada. As a result, the country's navy was unprepared for World War I.

Super-dreadnoughts

Within five years of the commissioning of Dreadnought, a new generation of more powerful "super-dreadnoughts" was being built. The British Orion class jumped an unprecedented 2,000 tons in displacement, introduced the heavier 13.5-inch (343 mm) gun, and placed all the main armament on the centreline (hence with some turrets superfiring over others). In the four years between Dreadnought and Orion, displacement had increased by 25%, and weight of broadside (the weight of ammunition that can be fired on a single bearing in one salvo) had doubled.

British super-dreadnoughts were joined by those built by other nations. The US Navy New York class, laid down in 1911, carried 14-inch (356 mm) guns in response to the British move and this calibre became standard. In Japan, two Fusō-class super-dreadnoughts were laid down in 1912, followed by the two Ise-class ships in 1914, with both classes carrying twelve 14-inch (356 mm) guns. In 1917, the Nagato class was ordered, the first super-dreadnoughts to mount 16-inch guns, making them arguably the most powerful warships in the world. All were increasingly built from Japanese rather than from imported components. In France, the Courbets were followed by three super-dreadnoughts of the Bretagne class, carrying 13.4-inch (340 mm) guns; another five Normandies were canceled on the outbreak of World War I. The aforementioned Brazilian dreadnoughts sparked a small-scale arms race in South America, as Argentina and Chile each ordered two super-dreadnoughts from the US and the United Kingdom, respectively. Argentina's Rivadavia and Moreno had a main armament equaling that of their Brazilian counterparts, but were much heavier and carried thicker armour. The British purchased both of Chile's battleships on the outbreak of the First World War. One, Almirante Latorre, was later repurchased by Chile.

Later British super-dreadnoughts, principally the Queen Elizabeth class, dispensed with the midships turret, freeing weight and volume for larger, oil-fired boilers. The new 15-inch (381 mm) gun gave greater firepower in spite of the loss of a turret, and there were a thicker armour belt and improved underwater protection. The class had a 25-knot (46 km/h; 29 mph) design speed, and they were considered the first fast battleships.

The design weakness of super-dreadnoughts, which distinguished them from post-1918 vessels, was armour disposition. Their design emphasized the vertical armour protection needed in short-range battles, where shells would strike the sides of the ship, and assumed that an outer plate of armour would detonate any incoming shells so that crucial internal structures such as turret bases needed only light protection against splinters. This was in spite of the ability to engage the enemy at 20,000 yd (18,000 m), ranges where the shells would descend at angles of up to thirty degrees ("plunging fire") and so could pierce the deck behind the outer plate and strike the internal structures directly. Post-war designs typically had 5 to 6 inches (130 to 150 mm) of deck armour laid across the top of single, much thicker vertical plates to defend against this. The concept of zone of immunity became a major part of the thinking behind battleship design. Lack of underwater protection was also a weakness of these pre-World War I designs, which originated before the use of torpedoes became widespread.

The United States Navy designed its 'Standard-type battleships', beginning with the Nevada class, with long-range engagements and plunging fire in mind; the first of these was laid down in 1912, four years before the Battle of Jutland taught the dangers of long-range fire to European navies. Important features of the standard battleships were "all or nothing" armour and "raft" construction—based on a design philosophy which held that only those parts of the ship worth giving the thickest possible protection were worth armouring at all, and that the resulting armoured "raft" should contain enough reserve buoyancy to keep the entire ship afloat in the event the unarmoured bow and stern were thoroughly punctured and flooded. This design proved its worth in the 1942 Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, when an ill-timed turn by South Dakota silhouetted her to Japanese guns. In spite of receiving 26 hits, her armoured raft remained untouched and she remained both afloat and operational at the end of action.

In action

The First World War saw no decisive engagements between battlefleets to compare with Tsushima. The role of battleships was marginal to the land fighting in France and Russia; it was equally marginal to the German war on commerce (Handelskrieg) and the Allied blockade.

By virtue of geography, the Royal Navy could keep the German High Seas Fleet confined to the North Sea with relative ease, but was unable to break the German superiority in the Baltic Sea. Both sides were aware, because of the greater number of British dreadnoughts, that a full fleet engagement would likely result in a British victory. The German strategy was, therefore, to try to provoke an engagement on favourable terms: either inducing a part of the Grand Fleet to enter battle alone, or to fight a pitched battle near the German coast, where friendly minefields, torpedo boats, and submarines could even the odds.

The first two years of war saw conflict in the North Sea limited to skirmishes by battlecruisers at the Battle of Heligoland Bight and Battle of Dogger Bank, and raids on the English coast. In May 1916, a further attempt to draw British ships into battle on favourable terms resulted in a clash of the battlefleets on 31 May to 1 June in the indecisive Battle of Jutland.

In the other naval theatres, there were no decisive pitched battles. In the Black Sea, Russian and Turkish battleships skirmished, but nothing more. In the Baltic Sea, action was largely limited to convoy raiding and the laying of defensive minefields. The Adriatic was in a sense the mirror of the North Sea: the Austro-Hungarian dreadnought fleet was confined to the Adriatic Sea by the Italian, British and French blockade but bombarded the Italians on several occasions, notably at Ancona in 1915. And in the Mediterranean, the most important use of battleships was in support of the amphibious assault at Gallipoli.

The course of the war illustrated the vulnerability of battleships to cheaper weapons. In September 1914, the U-boat threat to capital ships was demonstrated by successful attacks on British cruisers, including the sinking of three elderly British armoured cruisers by the German submarine U-9 in less than an hour. Mines continued to prove a threat when a month later the recently commissioned British super-dreadnought HMS Audacious struck one and sank in 1914. By the end of October, British strategy and tactics in the North Sea had changed to reduce the risk of U-boat attack. Jutland was the only major clash of dreadnought battleship fleets in history, and the German plan for the battle relied on U-boat attacks on the British fleet; and the escape of the German fleet from the superior British firepower was effected by the German cruisers and destroyers closing on British battleships, causing them to turn away to avoid the threat of torpedo attack. Further near-misses from submarine attacks on battleships led to growing concern in the Royal Navy about the vulnerability of battleships.

For the German part, the High Seas Fleet determined not to engage the British without the assistance of submarines, and since submarines were more needed for commerce raiding, the fleet stayed in port for much of the remainder of the war. Other theatres showed the role of small craft in damaging or destroying dreadnoughts. The two Austrian dreadnoughts lost in November 1918 were casualties of Italian torpedo boats and frogmen.

Battleship building from 1914 onwards

World War I

The outbreak of World War I largely halted the dreadnought arms race as funds and technical resources were diverted to more pressing priorities. The foundries which produced battleship guns were dedicated instead to the production of land-based artillery, and shipyards were flooded with orders for small ships. The weaker naval powers engaged in the Great War—France, Austria-Hungary, Italy and Russia—suspended their battleship programmes entirely. The United Kingdom and Germany continued building battleships and battlecruisers but at a reduced pace.

In the United Kingdom, Fisher returned to his old post as First Sea Lord; he had been created 1st Baron Fisher in 1909, taking the motto Fear God and dread nought. This, combined with a government moratorium on battleship building, meant a renewed focus on the battlecruiser. Fisher resigned in 1915 following arguments about the Gallipoli Campaign with the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill.

The final units of the Revenge and Queen Elizabeth classes were completed, though the last two battleships of the Revenge class were re-ordered as battlecruisers of the Renown class. Fisher followed these ships with the even more extreme Courageous class; very fast and heavily armed ships with minimal, 3-inch (76 mm) armour, called 'large light cruisers' to get around a Cabinet ruling against new capital ships. Fisher's mania for speed culminated in his suggestion for HMS Incomparable, a mammoth, lightly armoured battlecruiser.

In Germany, two units of the pre-war Bayern class were gradually completed, but the other two laid down were still unfinished by the end of the War. Hindenburg, also laid down before the start of the war, was completed in 1917. The Mackensen class, designed in 1914–1915, were begun but never finished.

Post-war

See also: List of battleships of World War IIIn spite of the lull in battleship building during the World War, the years 1919–1922 saw the threat of a renewed naval arms race between the United Kingdom, Japan, and the US. The Battle of Jutland exerted a huge influence over the designs produced in this period. The first ships which fit into this picture are the British Admiral class, designed in 1916. Jutland finally persuaded the Admiralty that lightly armoured battlecruisers were too vulnerable, and therefore the final design of the Admirals incorporated much-increased armour, increasing displacement to 42,000 tons. The initiative in creating the new arms race lay with the Japanese and United States navies. The United States Naval Appropriations Act of 1916 authorized the construction of 156 new ships, including ten battleships and six battlecruisers. For the first time, the United States Navy was threatening the British global lead. This programme was started slowly (in part because of a desire to learn lessons from Jutland), and never fulfilled entirely. The new American ships (the Colorado-class battleships, South Dakota-class battleships and Lexington-class battlecruisers), took a qualitative step beyond the British Queen Elizabeth class and Admiral classes by mounting 16-inch guns.

At the same time, the Imperial Japanese Navy was finally gaining authorization for its 'eight-eight battlefleet'. The Nagato class, authorized in 1916, carried eight 16-inch guns like their American counterparts. The next year's naval bill authorized two more battleships and two more battlecruisers. The battleships, which became the Tosa class, were to carry ten 16-inch guns. The battlecruisers, the Amagi class, also carried ten 16-inch guns and were designed to be capable of 30 knots, capable of beating both the British Admiral- and the US Navy's Lexington-class battlecruisers.

Matters took a further turn for the worse in 1919 when Woodrow Wilson proposed a further expansion of the United States Navy, asking for funds for an additional ten battleships and six battlecruisers in addition to the completion of the 1916 programme (the South Dakota class not yet started). In response, the Diet of Japan finally agreed to the completion of the 'eight-eight fleet', incorporating a further four battleships. These ships, the Kii class would displace 43,000 tons; the next design, the Number 13 class, would have carried 18-inch (457 mm) guns. Many in the Japanese navy were still dissatisfied, calling for an 'eight-eight-eight' fleet with 24 modern battleships and battlecruisers.

The British, impoverished by World War I, faced the prospect of slipping behind the US and Japan. No ships had been begun since the Admiral class, and of those only HMS Hood had been completed. A June 1919 Admiralty plan outlined a post-war fleet with 33 battleships and eight battlecruisers, which could be built and sustained for £171 million a year (approximately £9.93 billion today); only £84 million was available. The Admiralty then demanded, as an absolute minimum, a further eight battleships. These would have been the G3 battlecruisers, with 16-inch guns and high speed, and the N3-class battleships, with 18-inch (457 mm) guns. Its navy severely limited by the Treaty of Versailles, Germany did not participate in this three-way naval building competition. Most of the German dreadnought fleet was scuttled at Scapa Flow by its crews in 1919; the remainder were handed over as war prizes.

The major naval powers avoided the cripplingly expensive expansion programmes by negotiating the Washington Naval Treaty in 1922. The Treaty laid out a list of ships, including most of the older dreadnoughts and almost all the newer ships under construction, which were to be scrapped or otherwise put out of use. It furthermore declared a 'building holiday' during which no new battleships or battlecruisers were to be laid down, save for the British Nelson class. The ships which survived the treaty, including the most modern super-dreadnoughts of all three navies, formed the bulk of international capital ship strength through the interwar period and, with some modernisation, into World War II. The ships built under the terms of the Washington Treaty (and subsequently the London Treaties in 1930 and 1936) to replace outdated vessels were known as treaty battleships.

From this point on, the term 'dreadnought' became less widely used. Most pre-dreadnought battleships were scrapped or hulked after World War I, so the term 'dreadnought' became less necessary.

Notes

Footnotes

- The concept of an all-big-gun ship had been in development for several years before Dreadnought's construction. The Imperial Japanese Navy had begun work on an all-big-gun battleship in 1904, but finished the ship with a mixed armament. The United States Navy was building ships with a similar armament scheme, though Dreadnought was launched before any were completed.

- This was for two principal reasons. Improvements in torpedoes made close approaches to enemy ships risky. Meanwhile, in several battles, both Russian and Japanese vessels were able to score hits at considerably greater distances than their rangefinders were built to accommodate.

- At very close ranges, a projectile fired from a gun follows a flat trajectory, and the guns can be aimed by pointing them at the enemy. At greater ranges, the gunner has a more difficult problem as the gun needs to be elevated in order for the projectile to follow a proper ballistic trajectory to hit its target. This, therefore, needs accurate estimation (prediction) of the range to the target, which was one of the main problems of fire control. On warships, these problems are complicated by the fact that the ship will naturally roll in the water. Friedman 1978, p. 99.

- Lighter projectiles have a lower ratio of mass to frontal surface area, and so their velocity is reduced more quickly by air resistance.

- See Friedman 1985, p. 51, for discussion of alternative proposals for the Mississippi class.

- Additional advantage is gained by having a uniform armament. A mixed armament necessitates separate control for each type; owing to a variety of causes the range passed to 12-inch guns is not the range that will suit the 9.2-inch or 6-inch guns, although the distance of the target is the same." First Addendum to the Report of the Committee on Designs, quoted in Mackay 1973, p. 322.

- In the United Kingdom: "Fisher does not seem to have expressed interest in ... the ability to hit an adversary at long range by spotting salvoes. It is also very difficult to understand just when this method was first officially understood"; Mackay 1973, p. 322. And in America: "The possibility of gunnery confusion due to two calibers as close as 10 inches (250 mm) and 12 inches (300 mm) was never raised. For example, Sims and Poundstone stressed the advantages of homogeneity in terms of ammunition supply and the transfer of crews from the disengaged guns to replace wounded gunners. Friedman 1985, p. 55.

- In October W.L. Rogers of the Naval War College wrote a long and detailed memorandum on this question, pointing out that as ranges became longer the difference in accuracy between even 10-inch and 12-inch guns became enormous.Friedman 1985, p. 55; "The advantage at long range lies with the ship which carries the greatest number of guns of the largest type", Report of the Committee on Designs, quoted in Mackay 1973, p. 322.

- Fisher first firmly proposed the all-big-gun idea in a paper in 1904, where he called for battleships with sixteen 10-inch guns; by November 1904 he was convinced of the need for 12-inch guns. A 1902 letter, where he suggested powerful ships 'with equal fire all round', might have meant an all-big-gun design. Mackay 1973, p. 312.

- Friedman 1985, pp. 126–128. Friedman notes, for instance, the total loss of power in the turbo-electric drive of converted battlecruiser USS Saratoga (CV-3) after just one torpedo hit in World War II.

- Friedman 1985, pp. 104–105. While Nevada was designed and completed with oil-fired steam turbines, Oklahoma was designed and completed with oil-fired triple-expansion engines.

- Dreadnought (1906) cost £1,783,000, compared to the £1,540,000 for each of the Lord Nelson class. Eight years later the Queen Elizabeth class cost £2,300,000. Comparable figures today are 242 million; 209 million; 286 million. Original figures from Breyer, Battleships and Battlecruisers of the World, p.52, 141; comparisons from Measuring Worth UK CPI.

- The Nassau and Heligoland classes were war prizes. The Kaiser and König classes, and first two of the Bayern class were scuttled (though Baden was prevented from sinking by the British who refloated her and used her as a target ship and for experiments). Battleships under construction were scrapped instead of being completed.

- This process was well under way before the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty. Sixteen pre-dreadnoughts served during World War II in such roles as hulks, accommodation ships, and training vessels; two of the German training vessels Schlesien and Schleswig-Holstein undertook naval gunfire support in the Baltic.

Citations

- Sandler 2004, p. 149.

- Mackay 1973, p. 326, for instance.

- ^ Friedman 1985, p. 52.

- Jentschura, Jung & Mickel 1977, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 159.

- ^ Gardiner 1992, p. 15.

- Friedman 1985, p. 419.

- ^ Friedman 1978, p. 98.

- Fairbanks 1991.

- Sondhaus 2001, pp. 170–171.

- Lambert 1999, p. 77.

- ^ Friedman 1985, p. 53.

- ^ Lambert 1999, p. 78.

- Forczyk 2009, pp. 50, 72.

- Forczyk 2009, pp. 50, 56–57, 72.

- Gardiner & Lambert 2001, pp. 125–126.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 113, 331–332, 418.

- ^ Friedman 1985, p. 51.

- Friedman 1985, pp. 53–58.

- Parkes 1990, p. 426, quoting an INA paper of 9 April 1919 by Sir Philip Watts.

- Parkes 1990, p. 426.

- Parkes 1990, pp. 451–452.

- Breyer 1973, p. 113.

- Friedman 1985, p. 55.

- Fairbanks 1991, p. 250.

- Cuniberti 1903, pp. 407–409.

- Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 63.

- Breyer 1973, p. 331.

- Sumida 1995, pp. 619–621.

- ^ Breyer 1973, p. 115.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 46, 115.

- Friedman 1985, p. 62.

- Marder 1964, p. 542.

- Friedman 1985, p. 63.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 19–21.

- Breyer 1973, p. 85.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 54, 266.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 141–151.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 151–153.

- Kennedy 1991, p. 246.

- ^ Breyer 1973, p. 263.

- ^ Friedman 1978, p. 134.

- Friedman 1978, p. 132.

- Breyer 1973, p. 138.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 393–396.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 130–131.

- Friedman 1978, p. 129.

- ^ Friedman 1978, p. 130.

- Friedman 1978, p. 135.

- Breyer 1973, p. 72.

- Breyer 1973, p. 71.

- Breyer 1973, p. 84.

- Breyer 1973, p. 82.

- Breyer 1973, p. 214.

- Breyer 1973, p. 367.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 107, 115.

- Breyer 1973, p. 196.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 135–136.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 106–107.

- Breyer 1973, p. 159.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 113–116.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 116–122.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 7–8.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 54–61.

- ^ Gardiner 1992, p. 9.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 65–66.

- Friedman 1978, p. 67.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 66–67.

- Breyer 1973, p. 360.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 77–79.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 79–83.

- Friedman 1978, p. 95.

- Friedman 1978, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Friedman 1978, p. 91.

- ^ Breyer 1973, p. 46.

- Massie 2004, p. 474.

- Friedman 1985, pp. 75–76.

- Gardiner 1992, pp. 7–8.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 292, 295.

- Friedman 1985, p. 213.

- ^ Friedman 1978, p. 93.

- Mackay 1973, p. 269.

- Brown 2003, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Brown 2003, p. 23.

- Parkes 1990, pp. 582–583.

- Friedman 1978, p. 94.

- Sondhaus 2001, p. 198.

- Kennedy 1983, p. 218.

- Sondhaus 2001, p. 201.

- Herwig 1980, pp. 54–55.

- Sondhaus 2001, pp. 227–228.

- Keegan 1999, p. 281.

- Breyer 1973, p. 59.

- Sondhaus 2001, p. 203.

- Sondhaus 2001, pp. 203–204.

- Kennedy 1983, pp. 224–228.

- Sondhaus 2001, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Sondhaus 2001, p. 216.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 115, 196.

- ^ Friedman 1985, p. 69.

- The New York Times, 26 October 1915.

- Friedman 1985, p. 57.

- Gardiner & Gray 1985, p. 112.

- Gardiner & Gray 1985, p. 113.

- Friedman 1985, pp. 69–70.

- Evans & Peattie 1997, pp. 142–143.

- Breyer 1973, p. 333.

- ^ Sondhaus 2001, pp. 214–215.

- Gardiner & Gray 1985, p. 190.

- Sondhaus 2001, pp. 209–211.

- Sondhaus 2001, pp. 211–213.

- ^ Gardiner & Gray 1985, pp. 302–303.

- Gibbons 1983, p. 205.

- Breyer 1973, p. 393.

- Gibbons 1983, p. 195.

- Gardiner & Gray 1985, p. 378.

- Gardiner & Gray 1985, pp. 403–404.

- Breyer 1973, p. 320.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 450–455.

- Gardiner & Gray 1985, pp. 363–364, 366.

- Greger 1993, p. 252.

- Sondhaus 2001, p. 220.

- "Canada | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)". encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- Breyer 1973, p. 126.

- Sondhaus 2001, p. 214.

- Sondhaus 2001, pp. 214–216.

- Gardiner & Gray 1985, pp. 401, 408.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 140–144.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 75–79.

- Friedman 1985, pp. 202–203.

- Kennedy 1983, pp. 250–251.

- Keegan 1999, p. 289.

- Ireland & Grove 1997, pp. 88–95.

- Keegan 1999, pp. 234–235.

- Phillips 2013, p. .

- Kennedy 1983, pp. 256–257.

- Massie 2005, pp. 127–145.

- Kennedy 1983, pp. 245–248.

- Kennedy 1983, pp. 247–249.

- Breyer 1973, p. 61.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 61–62.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 277–284.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 62–63.

- Breyer 1973, p. 63.

- Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 171.

- Evans & Peattie 1997, p. 174.

- Breyer 1973, p. 356.

- Kennedy 1983, pp. 274–275.

- Breyer 1973, pp. 173–174.

- Gröner 1990, p. .

- Breyer 1973, pp. 69–70.

References

- Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battlecruisers of the World, 1905–1970. London: Macdonald and Jane's. ISBN 978-0-356-04191-9.

- Brown, D. K. (2003). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860–1905. Book Sales. ISBN 978-1-84067-529-0.

- Cuniberti, Vittorio (1903). "An Ideal Battleship for the British Fleet". All The World's Fighting Ships. London: F.T. Jane.

- Evans, David C.; Peattie, Mark R (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-192-8.

- Fairbanks, Charles (1991). "The Origins of the Dreadnought Revolution". International History Review. 13 (2): 246–272. doi:10.1080/07075332.1991.9640580.

- Forczyk, Robert (2009). Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship, Yellow Sea 1904–05. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-330-8.

- Friedman, Norman (1978). Battleship Design and Development 1905–1945. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-135-9.

- Friedman, Norman (1985). US Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-715-9.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1992). The Eclipse of the Big Gun. London: Conways. ISBN 978-0-85177-607-1.

- Gardiner, Robert; Lambert, Andrew, eds. (2001). Steam, Steel and Shellfire: The Steam Warship 1815–1905. Conway's History of the Ship. Book Sales. ISBN 978-0-7858-1413-9.

- Gray, Randal (1985). Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers: A Technical Directory of all the World's Capital Ships from 1860 to the Present Day. London: Salamander Books. ISBN 978-0-517-37810-6.

- Greger, René (1993). Schlachtschiffe der Welt (in German). Stuttgart: Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 978-3-613-01459-6.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships 1815–1945. Volume One: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Herwig, Holger (1980). "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Ireland, Bernard; Grove, Eric (1997). Jane's War At Sea 1897–1997. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-472065-4.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter; Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. London: Arms & Armor Press. ISBN 978-0-85368-151-9.