| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Telegraph key" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

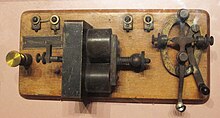

A straight key style of telegraph key – model J-38, a key used by U.S. military during World War II, and frequently re-used by radio amateurs A straight key style of telegraph key – model J-38, a key used by U.S. military during World War II, and frequently re-used by radio amateurs | |

| Type | Switch |

|---|---|

| Electronic symbol | |

| |

A telegraph key, clacker, tapper or morse key is a specialized electrical switch used by a trained operator to transmit text messages in Morse code in a telegraphy system. Keys are used in all forms of electrical telegraph systems, including landline (also called wire) telegraphy and radio (also called wireless) telegraphy. An operator uses the telegraph key to send electrical pulses (or in the case of modern CW, unmodulated radio waves) of two different lengths: short pulses, called dots or dits, and longer pulses, called dashes or dahs. These pulses encode the letters and other characters that spell out the message.

Types

The first telegraph key was invented by Alfred Vail, an associate of Samuel Morse. Since then the technology has evolved and improved, resulting in a range of key designs.

Straight keys

A straight key is the common telegraph key as seen in various movies. It is a simple bar with a knob on top and an electrical contact underneath. When the bar is pressed down against spring tension, it makes a closed electric circuit. Traditionally, American telegraph keys had flat topped knobs and narrow bars (frequently curved), while European telegraph keys had ball shaped knobs and thick bars. This appears to be purely a matter of culture and training, but the users of each are tremendously partisan.

Straight keys have been made in numerous variations for over 150 years and in numerous countries. They are the subject of an avid community of key collectors. The straight keys also had a shorting bar that closed the electrical circuit through the station when the operator was not actively sending messages. The shorting switch for an unused key was needed in telegraph systems wired in the style of North American railroads, in which the signal power was supplied from batteries only in telegraph offices at one or both ends of a line, rather than each station having its own bank of batteries, which was often used in Europe. The shorting bar completed the electrical path to the next station and all following stations, so that their sounders could respond to signals coming down the line, allowing the operator in the next town to receive a message from the central office. Although occasionally included in later keys for reasons of tradition, the shorting bar is unnecessary for radio telegraphy, except as a convenience to produce a steady signal for tuning the transmitter.

The straight key is simple and reliable, but the rapid pumping action needed to send a string of dots (or dits as most operators call them) poses some medically significant drawbacks.

Transmission speeds vary from 5 words (25 characters) per minute, by novice operators, up to about 30 words (150 characters) per minute by skilled operators. In the early days of telegraphy, a number of professional telegraphers developed a repetitive stress injury known as glass arm or telegraphers’ paralysis. "Glass arm" may be reduced or eliminated by increasing the side play of the straight key, by loosening the adjustable trunnion screws. Such problems can be avoided either by using good manual technique, or by only using side-to-side key types.

Alternative designs

In addition to the basic up-and-down telegraph key, telegraphers have been experimenting with alternate key designs from the beginning of telegraphy. Many are made to move side-to-side instead of up-and-down. Some of the designs, such as sideswipers (or bushwhackers) and semi-automatic keys operate mechanically.

Beginning in the mid-20th century electronic devices called "keyers" have been developed, which are operated by special keys of various designs generally categorized as single-paddle keys (also called sideswipers), and double-paddle keys (or "iambic" or "squeeze" keys). The keyer may be either an independent device that attaches to the transmitter in place of a telegraph key, or circuitry incorporated in modern amateurs' radios.

Sideswipers

The first widely accepted alternative key was the sideswiper or sidewinder, sometimes called a cootie key or bushwhacker. This key uses a side-to-side action with contacts on both the left and right and the arm spring-loaded to return to center; the operator may make a dit or dah by swinging the lever in either direction. A series of dits can be sent by rocking the arm back and forth.

This first new style of key was introduced in part to increase speed of sending, but more importantly to reduce the repetitive strain injury affecting telegraphers. The side-to-side motion reduces strain, and uses different muscles than the up-and-down motion (called "pounding brass"). Nearly all advanced keys use some form of side-to-side action.

The alternating action produces a distinctive rhythm or swing which noticeably affects the operator's transmission rhythm (known as ‘fist’). Although the original sideswiper is now rarely seen or used, when the left and right contacts are electrically separated a sideswiper becomes a modern single-paddle key (see below); likewise, a modern single-lever key becomes an old-style sideswiper when its two contacts are wired together.

Semi-automatic key

A popular side-to-side key is the semi-automatic key or bug, sometimes known as a Vibroplex key, after an early manufacturer of mechanical, semi-automatic keys. The original bugs were fully mechanical, based on a kind of simple clockwork mechanism, and required no electronic keyer. A skilled operator can achieve sending speeds in excess of 40 words per minute with a ‘bug’.

The benefit of the clockwork mechanism is that it reduces the motion required from the telegrapher's hand, which provides greater speed of sending, and it produces uniformly timed dits (dots, or short pulses) and maintains constant rhythm; consistent timing and rhythm are crucial for decoding the signal on the other end of the telegraph line.

The single paddle is held between the knuckle and the thumb of the right hand. When the paddle is pressed to the right (with the thumb), it kicks a horizontal pendulum which then rocks against the contact point, sending a series of short pulses (dits or dots) at a speed which is controlled by the pendulum’s length. When the paddle is pressed toward the left (with the knuckle) it makes a continuous contact suitable for sending dahs (dashes); the telegrapher remains responsible for timing the dahs to proportionally match the dits. The clockwork pendulum needs the extra kick that the stronger thumb press provides, which established the standard left-right paddle directions for the dit-dah assignments that persists on the paddles on 21st century electronic keys. A few semi-automatic keys were made with mirror-image mechanisms for left-handed telegraphers.

Electronic keyers and paddle keys

Like semi-automatic keys, the telegrapher operates an electronic keyer by tapping a paddle key, swinging its lever(s) from side-to-side. When pressed to one side (usually left), the keyer electronics generate a series of dahs; when pressed to the other side (usually right), a series of dits. Keyers work with two different types of keys: Single paddle and double paddle keys.

Like semi-automatic keys, pressing the paddle on one side produces a dit and the other a dah. Single paddle keys are also called single lever keys or sideswipers, the same name as the older side-to-side key design they greatly resemble. Double paddle keys are also called "iambic" keys or "squeeze" keys. Also like the old semi-automatic keys, the conventional assignment of the paddle directions (for a right-handed telegrapher) is that pressing a paddle with the right thumb (pressing the single paddle rightward, or for a double-paddle key, pressing the left paddle with the thumb, rightwards towards the center) creates a series of dits. Pressing a paddle with the right knuckle (hence swinging a single paddle leftward, or the right paddle on a double-paddle key leftward to the center) creates a series of dahs. Left-handed telegraphers sometimes elect to reverse the electrical contacts, so their left-handed keying is a mirror image of standard right-handed keying.

Single paddle keys are essentially the same as the original sideswiper keys, with the left and right electrical contacts wired separately. Double-paddle keys have one arm for each of the two contacts, each arm held away from the common center by a spring; pressing either of the paddles towards the center makes contact, the same as pressing a single-lever key to one side. For double-paddle keys wired to an "iambic" keyer, squeezing both paddles together makes a double-contact, which causes the keyer to send alternating dits and dahs (or dahs and dits, depending on which lever makes first contact).

Most electronic keyers include dot and dash memory functions, so the operator does not need to use perfect spacing between dits and dahs or vice versa. With dit or dah memory, the operator's keying action can be about one dit ahead of the actual transmission. The electronics in the keyer adjusts the timing so that the output of each letter is machine-perfect. Electronic keyers allow very high speed transmission of code.

Using a keyer in what's called "iambic" mode requires a key with two paddles: One paddle produces dits and the other produces dahs. Pressing both at the same time (a "squeeze") produces an alternating dit-dah-dit-dah ( ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ) sequence, which starts with a dit if the dit side makes contact first, or a dah ( ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ) if the dah side connects first.

An additional advantage of electronic keyers over semiautomatic keys is that code speed is easily changed with electronic keyers, just by turning a knob. With a semiautomatic key, the location of the pendulum weight and the pendulum spring tension and contact must all be repositioned and rebalanced to change the dit speed.

Double-lever paddles

Keys having two separate levers, one for dits and the other for dahs are called dual or dual-lever paddles. With a dual paddle both contacts may be closed simultaneously, enabling the "iambic" functions of an electronic keyer that is designed to support them: By pressing both paddles (squeezing the levers together) the operator can create a series of alternating dits and dahs, analogous to a sequence of iambs in poetry. For that reason, dual paddles are sometimes called squeeze keys or iambic keys. Typical dual-paddle keys' levers move horizontally, like the earlier single-paddle keys, as opposed to how the original "straight-keys'" arms move up-and-down.

Whether the sequence begins with a dit or a dah is determined by which lever makes contact first: If the dah lever is closed first, then the first element will be a dah, so the string of elements will be similar to a sequence of trochees in poetry, and the method could as logically be called "trochaic keying" ( ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ). If the dit lever makes first contact, then the string begins with a dit ( ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ).

Insofar as iambic keying is a function of the electronic keyer, it is not correct, technically, to refer to a dual paddle key itself as "iambic", although this is commonly done in marketing. A dual paddle key is required for iambic sending, which also requires an iambic keyer. But any single- or dual-paddle key can be used non-iambicly, without squeezing, and there were electronic keyers made which did not have iambic functions.

Iambic keying or squeeze keying reduces the key strokes or hand movements necessary to make some characters, e.g. the letter C, which can be sent by merely squeezing the two paddles together. With a single-paddle or non-iambic keyer, the hand motion would require alternating four times for C (dah-dit-dah-dit ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ).

The efficiency of iambic keying has recently been discussed in terms of movements per character and timings for high speed CW, with the author concluding that the timing difficulties of correctly operating a keyer iambicly at high speed outweigh any small benefits.

Iambic keyers function in one of at least two major modes: Mode A and mode B. There is a third, rarely available mode U.

Mode A

Mode A is the original iambic mode, in which alternate dots and dashes are produced as long as both paddles are depressed. Mode A is essentially "what you hear is what you get": When the paddles are released, the keying stops with the last dot or dash that was being sent while the paddles were held.

Mode B

Mode B is the second mode, which devolved from a logic error in an early iambic keyer. Over the years iambic mode B has become something of a standard and is the default setting in most keyers.

In mode B, dots and dashes are produced as long as both paddles are depressed. When the paddles are released, the keying continues by sending one more element than has already been heard. I.e., if the paddles were released during a dah then the last element sent will be a following dit; if the paddles were released during a dit then the sequence will end with the following dah.

Users accustomed to one mode may find it difficult to adapt to the other, so most modern keyers allow selection of the desired mode.

Mode U

A third electronic keyer mode useful with a dual paddle is the "Ultimatic" mode (mode U), so-called for the brand name of the electronic keyer that introduced it. In the Ultimatic keying mode, the keyer will switch to the opposite element if the second lever is pressed before the first is released (that is, squeezed).

Single-lever paddle keys

A single-lever paddle key has separate contacts for dits and dahs, but there is no ability to make both contacts simultaneously by squeezing the paddles together for iambic mode.

When a single-paddle key is used with an electronic keyer, continuous dits are created by holding the dit-side paddle ( ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ...); likewise, continuous dahs are created by holding the dah paddle ( ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ...).

A single-paddle key can non-iambicly operate any electronic keyer, whether or not it even offers iambic functions, and regardless of whether the keyer iambically operates in mode A, B, or U.

Non-telegraphic keys

Simple telegraph-like keys were long used to control the flow of electricity in laboratory tests of electrical circuits. Often, these were simple "strap" keys, in which a bend in the key lever provided the key's spring action.

Telegraph-like keys were once used in the study of operant conditioning with pigeons. Starting in the 1940s, initiated by B. F. Skinner at Harvard University, the keys were mounted vertically behind a small circular hole about the height of a pigeon's beak in the front wall of an operant conditioning chamber. Electromechanical recording equipment detected the closing of the switch whenever the pigeon pecked the key. Depending on the psychological questions being investigated, keypecks might have resulted in the presentation of food or other stimuli.

Operators' "fist"

With straight keys, side-swipers, and, to an extent, bugs, each and every telegrapher has their own unique style or rhythm pattern when transmitting a message. An operator's style is known as their "fist".

Since every fist is unique, other telegraphers can usually identify the individual telegrapher transmitting a particular message. This had a huge significance during the first and second World Wars, since the on-board telegrapher's "fist" could be used to track individual ships and submarines, and for traffic analysis.

However, with electronic keyers (either single- or double-paddle) this is no longer the case: Keyers produce uniformly "perfect" code at a set speed, which is altered at the request of the receiver, usually not the sender. Only inter-character and inter-word spacing remain unique to the operator, and can produce a less clear semblance of a "fist".

See also

Explanatory notes

- The longer shape of the ball-headed knobs is intended to encourage the operator to incline the hand and grasp the key more lightly, to put less strain on the arm. The design is intended to reduce repetitive strain injury once common among telegraphers, which telegraphers called "glass arm", and medical literature referred to as telegraphers’ paralysis. However it is possible to injure one's arm by improperly holding the key, or striking with too much force (called "pounding brass") with either type of up-and-down key.

- ^

The name "iambic" comes from the rhythm in poetry, which the sound of the beat of alternating dits and dahs resembles. E.g.

- "Of cloudless climes and starry skies" ≈ dit dah dit dah dit dah dit dah.

- "Double, double, toil and trouble" ≈ dah dit, dah dit, dah dit, dah dit.

References

- "Telegraph Key". National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- Noll, A. Michael (2001). Principles of Modern Communications Technology. Artech House via Google Books. p. 208. ISBN 1-58053-284-5. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- "CW Mode". ARRL. The National Association for Amateur Radio. Archived from the original on 15 December 2024. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- Elements of Telegraph Operating. Google Books: International Correspondence Schools. p. 9. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- Cocconcelli, Marco and Fonte, Cosimo. Explorations in the History and Heritage of Machines and Mechanisms: Dynamic Analysis of a Semiautomatic Telegraph Key (7th ed.). Google Books: Springer Nature. p. 383. ISBN 978-3-030-98498-4. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - How to operate a straight key on YouTube

- Technique of hand sending (1944) on YouTube

- Straight key hand sending technique approved by professionals on YouTube

- How to properly adjust and use a Vibroplex bug. YouTube (video). Archived from the original on 2021-12-11 – via Ghostarchive. "Wayback Machine archive". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2014-01-26. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Good, Anthony, K3NG (22 April 2023). "Arduino CW keyer". Radio artisan (blog). Archived from the original on 20 February 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2024 – via radioartisan.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - How to use an iambic keyer on YouTube.

- Emm, Marshall G., N1FN. "Iambic keying – debunking the myth" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-25. Retrieved 2022-11-09 – via morsex.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

- Sparks Telegraph Key Review - A pictorial review of telegraphy and telegraph keys with an emphasis on spark (wireless) telegraphy.

- The Telegraph Office - A resource for telegraph key collectors and historians

- The Keys of N1KPR Archived 2013-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- The Art and Skill of Radio Telegraphy

- Development of the Morse Key

- Telegraph Keys - An online resource for identification of all types of telegraph instruments