Text messaging, or simply texting, is the act of composing and sending electronic messages, typically consisting of alphabetic and numeric characters, between two or more users of mobile phones, tablet computers, smartwatches, desktops/laptops, or another type of compatible computer. Text messages may be sent over a cellular network or may also be sent via satellite or Internet connection.

The term originally referred to messages sent using the Short Message Service (SMS) on mobile devices. It has grown beyond alphanumeric text to include multimedia messages using the Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) and Rich Communication Services (RCS), which can contain digital images, videos, and sound content, as well as ideograms known as emoji (happy faces, sad faces, and other icons), and on various instant messaging apps. Text messaging has been an extremely popular medium of communication since the turn of the century and has also influenced changes in society.

Overview

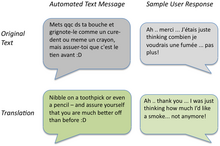

Text messages are used for personal, family, business, and social purposes. Governmental and non-governmental organizations use text messaging for communication between colleagues. In the 2010s, the sending of short informal messages became an accepted part of many cultures, as happened earlier with emailing. This makes texting a quick and easy way to communicate with friends, family, and colleagues, including in contexts where a call would be impolite or inappropriate (e.g., calling very late at night or when one knows the other person is busy with family or work activities). Like e-mail and voicemail, and unlike calls (in which the caller hopes to speak directly with the recipient), texting does not require the caller and recipient to both be free at the same moment; this permits communication even between busy individuals. Text messages can also be used to interact with automated systems, for example, to order products or services from e-commerce websites or to participate in online contests. Advertisers and service providers use direct text marketing to send messages to mobile users about promotions, payment due dates, and other notifications instead of using postal mail, email, or voicemail.

Terminology

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The service is referred to by different colloquialisms depending on the region. It may simply be referred to as a "text" in North America, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and the Philippines; an "SMS" in most of mainland Europe; or an "MMS" or "SMS" in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. The sender of a text message is commonly referred to as a "texter".

History

See also: SMS § Developmental historyThe electrical telegraph systems, developed in the early 19th century, used electrical signals to send text messages. In the late 19th century, wireless telegraphy was developed using radio waves.

In 1933, the German Reichspost (Reich postal service) introduced the first "telex" service.

The University of Hawaii began using radio to send digital information as early as 1971, using ALOHAnet. Friedhelm Hillebrand conceptualised SMS in 1984 while working for Deutsche Telekom. Sitting at a typewriter at home, Hillebrand typed out random sentences and counted every letter, number, punctuation mark, and space. Almost every time, the messages contained fewer than 160 characters, thus giving the basis for the limit one could type via text messaging. With Bernard Ghillebaert of France Télécom, he developed a proposal for the GSM (Groupe Spécial Mobile) meeting in February 1985 in Oslo. The first technical solution evolved in a GSM subgroup under the leadership of Finn Trosby. It was further developed under the leadership of Kevin Holley and Ian Harris (see Short Message Service). SMS forms an integral part of Signalling System No. 7 (SS7). Under SS7, it is a "state" with 160 characters of data, coded in the ITU-T "T.56" text format, that has a "sequence lead in" to determine different language codes and may have special character codes that permit, for example, sending simple graphs as text. This was part of ISDN (Integrated Services Digital Network), and since GSM is based on this, it made its way to the mobile phone. Messages could be sent and received on ISDN phones, and these can send SMS to any GSM phone. The possibility of doing something is one thing; implementing it is another, but systems existed in 1988 that sent SMS messages to mobile phones (compare ND-NOTIS).

SMS messaging was used for the first time on 3 December 1992, when Neil Papworth, a 22-year-old test engineer, used a computer to send the text message "Merry Christmas" via the Vodafone network to the phone of Richard Jarvis, who was at a party in Newbury, Berkshire celebrating the event. Papworth later said "it didn't feel momentous at all". Modern SMS text messaging is usually sent from one mobile phone to another. Finnish Radiolinja became the first network to offer a commercial person-to-person SMS text messaging service in 1994. When Radiolinja's domestic competitor, Telecom Finland (now part of TeliaSonera), also launched SMS text messaging in 1995 and the two networks offered cross-network SMS functionality, Finland became the first nation where SMS text messaging was offered on a competitive as well as a commercial basis. GSM was allowed in the United States, but the radio frequencies were blocked and awarded to US "Carriers" to use US technology, which limited development of mobile messaging services in the US. The GSM in the US had to use a frequency allocated for private communication services (PCS) – what the ITU frequency régime had blocked for DECT (Digital Enhanced Cordless Telecommunications) – a 1,000-foot range picocell, but it survived. American Personal Communications (APC), the first GSM carrier in America, provided the first text-messaging service in the United States. Sprint Telecommunications Venture, a partnership of Sprint Corp. and three large cable-TV companies, owned 49 percent of APC. The Sprint venture was the largest single buyer at a government-run spectrum auction that raised $7.7 billion in 2005 for PCS licenses. APC operated under the brand name Sprint Spectrum and launched its service on 15 November 1995, in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland. Vice President Al Gore in Washington, D.C., made the initial phone call to launch the network, calling Mayor Kurt Schmoke in Baltimore.

Initial growth of text messaging worldwide was slow, with customers in 1995 sending on average only 0,4 messages per GSM customer per month. One factor in the slow take-up of SMS was that operators were slow to set up charging systems, especially for prepaid subscribers, and to eliminate billing fraud, which was possible by changing SMSC settings on individual handsets to use the SMSCs of other operators. Over time, this issue was eliminated by switch billing instead of billing at the SMSC and by new features within SMSCs that allowed the blocking of foreign mobile users sending messages through them. SMS is available on a wide range of networks, including 3G networks. However, not all text-messaging systems use SMS; some notable alternate implementations of the concept include J-Phone's SkyMail and NTT Docomo's Short Mail, both in Japan. E-mail messaging from phones, as popularized by NTT Docomo's i-mode and the RIM BlackBerry, also typically use standard mail protocols such as SMTP over TCP/IP. As of 2007, text messaging was the most widely used mobile data service, with 74% of all mobile phone users worldwide, or 2.4 billion out of 3.3 billion phone subscribers, being active users of the Short Message Service at the end of 2007. In countries such as Finland, Sweden, and Norway, over 85% of the population used SMS. The European average was about 80%, and North America was rapidly catching up, with over 60% active users of SMS by end of 2008. The largest average usage of the service by mobile phone subscribers occurs in the Philippines, with an average of 27 texts sent per day per subscriber.

Uses

Text messaging is most often used between private mobile phone users, as a substitute for voice calls in situations where voice communication is impossible or undesirable (e.g., during a school class or a work meeting). Texting is also used to communicate very brief messages, such as informing someone that you will be late or reminding a friend or colleague about a meeting. As with e-mail, informality and brevity have become an accepted part of text messaging. Some text messages such as SMS can also be used for the remote control of home appliances. It is widely used in domotics systems. Some amateurs have also built their own systems to control (some of) their appliances via SMS. A Flash SMS is a type of text message that appears directly on the main screen without user interaction and is not automatically stored in the inbox. It can be useful in cases such as an emergency (e.g., fire alarm) or confidentiality (e.g., one-time password).

SMS has historically been particularly popular in Europe, Asia (excluding Japan; see below), the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, while also gaining influence in Africa. Popularity has grown to a sufficient extent that the term texting (used as a verb meaning the act of mobile phone users sending short messages back and forth) has entered the common lexicon. In 2012, young Asians considered SMS as the most popular mobile phone application. In the same year, 50 percent of American teens send 50 text messages or more per day, making it their most frequent form of communication. In 2004 in China, SMS was very popular and brought service providers significant profit (18 billion short messages were sent in 2001).

It has been a very influential and powerful tool in the Philippines, where in 2008 the average user sent 10–12 text messages a day. The same year, the Philippines alone sent on average over 1 billion text messages a day, more than the annual average SMS volume of the countries in Europe, and even China and India. SMS saw hugely popular in India, where youngsters often exchanged many text messages, and companies provide alerts, infotainment, news, cricket scores updates, railway/airline booking, mobile billing, and banking services on SMS.

Similarly, in 2008, text messaging played a primary role in the implication of former Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick in an SMS sex scandal. Short messages are particularly popular among young urbanites. In many markets, the service is comparatively cheap. For example, in Australia, a message typically costs between A$0.20 and $0.25 to send (some prepaid services charge $0.01 between their own phones), compared with a voice call, which costs somewhere between $0.40 and $2.00 per minute (commonly charged in half-minute blocks). The service is enormously profitable to the service providers. At a typical length of only 190 bytes (including protocol overhead), more than 350 of these messages per minute can be transmitted at the same data rate as a usual voice call (9 kbit/s). There are also free SMS services available, which are often sponsored, that allow sending and receiving SMS from a PC connected to the Internet. Mobile service providers in New Zealand, such as One NZ and Spark New Zealand, provided up to 2000 SMS messages for NZ$10 per month. Users on these plans sent on average 1500 SMS messages every month. Text messaging became so popular that advertising agencies and advertisers jumped into the text messaging business. Services that provide bulk text message sending are also becoming a popular way for clubs, associations, and advertisers to reach a group of opt-in subscribers quickly.

In 2013, research suggested that Internet-based mobile messaging would grow to equal the popularity of SMS by the end of 2013, with nearly 10 trillion messages being sent through each technology. Services such as Facebook Messenger/WhatsApp, Signal (software), Snapchat, Telegram (software), Viber have led to a decline in the use of SMS in parts of the world. A survey conducted by MetrixLabs showed that 63% of Baby Boomers, 63% of Generation X, and 67% of Generation Y said that they used instant messengers in place of texting. A Facebook survey showed that 65% of people surveyed thought that messaging applications made group messaging easier.

Applications

Microblogging

Main article: MicrobloggingOf many texting trends, a system known as microblogging has surfaced, which consists of a miniaturized blog, inspired mainly by people's tendency to jot down informal thoughts and post them online. They consist of websites like X (formerly Twitter) and its Chinese equivalent Weibo (微博). As of 2016, 21% of all American adults used Twitter. As of 2017, Weibo had 340 million active users.

Emergency services

In some countries, text messages can be used to contact emergency services. In the UK, text messages can be used to call emergency services only after registering with the emergency SMS service. This service is primarily aimed at people who, because of disability, are unable to make a voice call. It has recently been promoted as a means for walkers and climbers to call emergency services from areas where a voice call is not possible due to low signal strength.

In the US, there is a move to require both traditional operators and over-the-top messaging providers to support texting to 911. In Asia, SMS is used for tsunami warnings and in Europe, SMS is used to inform individuals of imminent disasters. Since the location of a handset is known, systems can alert everyone in an area that the events have made impossible to pass through e.g. an avalanche. A similar system, known as Emergency Alert, is used in Australia to notify the public of impending disasters through both SMS and landline phone calls. These messages can be sent based on either the location of the phone or the address to which the handset is registered.

In the early 2020s, device manufacturers have begun to integrate satellite messaging connectivity and satellite emergency services into conventional mobile phones for use in remote regions, where there is no reliable terrestrial cellular network.

Reminders of medical appointments

SMS messages are used in some countries as reminders of medical appointments. Missed outpatient clinic appointments cost the National Health Service (England) more than £600 million ($980 million) a year. SMS messages are thought to be more cost-effective, swifter to deliver, and more likely to receive a faster response than letters. A 2012 study by Sims and colleagues examined the outcomes of 24,709 outpatient appointments scheduled in mental health services in South-East London. The study found that SMS message reminders could reduce the number of missed psychiatric appointments by 25–28%, representing a potential national yearly saving of over £150 million.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, medical facilities in the United States are using text messaging to coordinate the appointment process, including reminders, cancellations, and safe check-in. US-based cloud radiology information system vendor AbbaDox includes this in their patient engagement services.

Commercial uses

Short codes

Short codes are special telephone numbers, shorter than full telephone numbers, that can be used to address SMS and MMS messages from mobile phones or fixed phones. There are two types of short codes: dialling and messaging.

Text messaging gateway providers

SMS gateway providers facilitate the SMS traffic between businesses and mobile subscribers, being mainly responsible for carrying mission-critical messages, SMS for enterprises, content delivery and entertainment services involving SMS, e.g., TV voting. Considering SMS messaging performance and cost, as well as the level of text messaging services, SMS gateway providers can be classified as resellers of the text messaging capability of another provider's SMSC or offering the text messaging capability as an operator of their own SMSC with SS7. SMS messaging gateway providers can provide gateway-to-mobile (Mobile Terminated–MT) services. Some suppliers can also supply mobile-to-gateway (text-in or Mobile Originated/MO services). Many operate text-in services on short codes or mobile number ranges, whereas others use lower-cost geographic text-in numbers.

Premium content

SMS has been widely used for delivering digital content, such as news alerts, financial information, pictures, GIFs, logos and ringtones. Such messages are also known as premium-rated short messages (PSMS). The subscribers are charged extra for receiving this premium content, and the amount is typically divided between the mobile network operator and the value added service provider (VASP), either through revenue share or a fixed transport fee. Services like 82ASK and Any Question Answered have used the PSMS model to enable rapid response to mobile consumers' questions, using on-call teams of experts and researchers. In November 2013, amidst complaints about unsolicited charges on bills, major mobile carriers in the US agreed to stop billing for PSMS in 45 states, effectively ending its use in the United States.

Outside the United States, premium short messages have been used for "real-world" services. For example, some vending machines now allow payment by sending a premium-rated short message, so that the cost of the item bought is added to the user's phone bill or subtracted from the user's prepaid credits. Recently, premium messaging companies have come under fire from consumer groups due to a large number of consumers racking up huge phone bills. A new type of free-premium or hybrid-premium content has emerged with the launch of text-service websites. These sites allow registered users to receive free text messages when items they are interested in go on sale, or when new items are introduced. An alternative to inbound SMS is based on long numbers (international mobile number format, e.g., +44 7624 805000, or geographic numbers that can handle voice and SMS, e.g., 01133203040), which can be used in place of short codes or premium-rated short messages for SMS reception in several applications, such as TV voting, product promotions and campaigns. Long numbers are internationally available, as well as enabling businesses to have their own number, rather than short codes, which are usually shared across a lot of brands. Additionally, long numbers are non-premium inbound numbers.

In workplaces

The use of text messaging for workplace purposes grew significantly during the mid-2000s. As companies seek competitive advantages, many employees used new technology, collaborative applications, and real-time messaging such as SMS, instant messaging, and mobile communications to connect with teammates and customers. Some practical uses of text messaging include the use of SMS for confirming delivery or other tasks, for instant communication between a service provider and a client (e.g., a payment card company and a consumer), and for sending alerts. Several universities have implemented a system of texting students and faculties campus alerts. One such example is Penn State.

As text messaging has proliferated in business, so too have regulations governing its use. One regulation specifically governing the use of text messaging in financial-services firms engaged in stocks, equities, and securities trading is Regulatory Notice 07-59, Supervision of Electronic Communications, December 2007, issued to member firms by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). In Regulatory Notice 07-59, FINRA noted that "electronic communications", "e-mail", and "electronic correspondence" may be used interchangeably and can include such forms of electronic messaging as instant messaging and text messaging. Industry has had to develop new technology to allow companies to archive their employees' text messages.

Security, confidentiality, reliability, and speed of SMS are among the most important guarantees industries such as financial services, energy and commodities trading, health care and enterprises demand in their mission-critical procedures. One way to guarantee such a quality of text messaging lies in introducing SLAs (Service Level Agreement), which are common in IT contracts. By providing measurable SLAs, corporations can define reliability parameters and set up a high quality of their services. Just one of many SMS applications that have proven highly popular and successful in the financial services industry is mobile receipts. In January 2009, Mobile Marketing Association (MMA) published the Mobile Banking Overview for financial institutions in which it discussed the advantages and disadvantages of mobile channel platforms such as Short Message Services (SMS), Mobile Web, Mobile Client Applications, SMS with Mobile Web and Secure SMS.

Mobile interaction services are an alternative way of using SMS in business communications with greater certainty. Typical business-to-business applications are telematics and Machine-to-Machine, in which two applications automatically communicate with each other. Incident alerts are also common, and staff communications are also another use for B2B scenarios. Businesses can use SMS for time-critical alerts, updates, and reminders, mobile campaigns, content and entertainment applications. Mobile interaction can also be used for consumer-to-business interactions, such as media voting and competitions, and consumer-to-consumer interaction, for example, with mobile social networking, chatting and dating.

Text messaging is widely used in business settings; as well, it is used in many civil service and non-governmental organization workplaces. The U.S. And Canadian civil service both adopted BlackBerry smartphones in the 2000s.

Group texts

Group texts involve more than two users. They are often used when it is helpful to message many people at once, such as inviting multiple people to an event or arranging groups. They are also used in business for marketing and other customer notifications as well as intracompany communication.

Group texts are often sent as MMS messages and therefore require an internet connection to send instead of using the sender's text messaging plan.

Online SMS services

There are a growing number of websites that allow users to send free SMS messages online. Some websites provide free SMS for promoting premium business packages.

Worldwide use

Europe

In 2003, Europe followed next behind Asia in terms of the popularity of the use of SMS. That year, an average of 16 billion messages were sent each month. Users in Spain sent a little more than fifty messages per month on average in 2003. In Italy, Germany and the United Kingdom, the figure was around 35–40 SMS messages per month. In each of these countries, the cost of sending an SMS message varied from €0.04–0.23, depending on the payment plan (with many contractual plans including all or several texts for free). In the United Kingdom, text messages are charged between £0.05–0.12. Curiously, France did not take to SMS in the same way, sending just under 20 messages on average per user per month. France has the same GSM technology as other European countries, so the uptake is not hampered by technical restrictions.

In the Republic of Ireland, in 2012, 1.5 billion messages were sent every quarter, on average 114 messages per person per month. In the United Kingdom, as of March 2012, over 1 billion text messages were sent every week. The Eurovision Song Contest organized the first pan-European SMS voting in 2002, as a part of the voting system (there was also a voting over traditional landline phone lines). In 2005, the Eurovision Song Contest organized the biggest televoting ever (with SMS and phone voting). During roaming, (that is, when a user connects to another network in different country from their own) the prices may be higher, but in July 2009, EU legislation went into effect limiting this price to €0.11.

Mobile service providers in Finland offered contracts in which users can send 1000 text messages a month for €10. In Finland, which has very high mobile phone ownership rates, some TV channels began "SMS chat", which involved sending short messages to a phone number, and the messages would be shown on TV. Chats are always moderated, which prevents users from sending offensive material to the channel. The craze evolved into quizzes and strategy games and then faster-paced games designed for television and SMS control. Games require users to register their nicknames and send short messages to control a character onscreen. Messages usually cost 0.05 to 0.86 Euro apiece, and games can require the player to send dozens of messages. In December 2003, a Finnish TV channel, MTV3, put a Santa Claus character on-air reading aloud text messages sent in by viewers. On 12 March 2004, the first entirely "interactive" TV channel, VIISI, began operation in Finland. However, SBS Finland Oy took over the channel and turned it into a music channel named The Voice in November 2004. In 2006, the Prime Minister of Finland, Matti Vanhanen, made the news when he allegedly broke up with his girlfriend with a text message. In 2007, the first book written solely in text messages, Viimeiset viestit (Last Messages), was released by Finnish author Hannu Luntiala. It is about an executive who travels through Europe and India.

United States

In the United States, text messaging is very popular; as reported by CTIA in December 2009, the 286 million US subscribers sent 152.7 billion text messages per month, for an average of 534 messages per subscriber per month. The Pew Research Center found in May 2010 that 72% of U.S. adult cellphone users send and receive text messages. CTIA reported in 2022 that 2 trillion SMS and MMS were sent in the United States in 2021, showing continued popularity of the technology.

In the U.S., SMS is often charged both at the sender and at the destination, but, unlike phone calls, it cannot be rejected or dismissed. The reasons for lower uptake than other countries are varied. Many users have unlimited "mobile-to-mobile" minutes, high monthly minute allotments, or unlimited service. Moreover, "push to talk" services offer the instant connectivity of SMS and are typically unlimited. The integration between competing providers and technologies necessary for cross-network text messaging was not initially available. Some providers originally charged extra for texting, reducing its appeal. In the third quarter of 2006, at least 12 billion text messages were sent on AT&T's network, up almost 15% from the preceding quarter.

While texting is mainly popular among people from 13 to 22 years old, it is also increasing among adults and business users. The age that a child receives their first cell phone has also decreased, making text messaging a popular way of communicating. The number of texts sent in the US has gone up over the years as the price has gone down to an average of $0.10 per text sent and received. To convince more customers to buy unlimited text messaging plans, some major cellphone providers have increased the price to send and receive text messages from $.15 to $.20 per message. This is over $1,300 per megabyte. Many providers offer unlimited plans, which can result in a lower rate per text, given sufficient volume.

Japan

Japan was among the first countries to adopt short messages widely, with pioneering non-GSM services including J-Phone's SkyMail and NTT Docomo's Short Mail. Japanese adolescents first began text messaging, because it was a cheaper form of communication than the other available forms. Thus, Japanese theorists created the selective interpersonal relationship theory, claiming that mobile phones can change social networks among young people (classified as 13- to 30-year-olds). They theorized this age group had extensive but low-quality relationships with friends, and mobile phone usage may facilitate improvement in the quality of their relationships. They concluded this age group prefers "selective interpersonal relationships in which they maintain particular, partial, but rich relations, depending on the situation". The same studies showed participants rated friendships in which they communicated face-to-face and through text messaging as being more intimate than those in which they communicated solely face-to-face. This indicates participants make new relationships with face-to-face communication at an early stage, but use text messaging to increase their contact later on. As the relationships between participants grew more intimate, the frequency of text messaging also increased. However, short messaging has been largely rendered obsolete by the prevalence of mobile Internet e-mail, which can be sent to and received from any e-mail address, mobile or otherwise. That said, while usually presented to the user simply as a uniform "mail" service (and most users are unaware of the distinction), the operators may still internally transmit the content as short messages, especially if the destination is on the same network.

China

Text messaging has historically been popular and cheap in China. About 700 billion messages were sent in 2007. Text message spam has also been a problem in China. In 2007, 353.8 billion spam messages were sent, up 93% from the previous year. It is about 12.44 messages per week per person. In 2010, it was routine that the People's Republic of China government monitored text messages across the country for illegal content. Among Chinese migrant workers with little formal education, it is common to refer to SMS manuals when text messaging. These manuals are published as cheap, smaller-than-pocket-size booklets that offer diverse linguistic phrases to utilize as messages.

Philippines

SMS was introduced to selected markets in the Philippines in 1995. In 1998, Philippine mobile service providers launched SMS more widely across the country, with initial television marketing campaigns targeting hearing-impaired users. The service was initially free with subscriptions, but Filipinos quickly exploited the feature to communicate for free instead of using voice calls, which they would be charged for. After telephone companies realized this trend, they began charging for SMS. The rate across networks is 1 peso per SMS (about US$0.023). Even after users were charged for SMS, it remained cheap, about one-tenth of the price of a voice call. This low price led to about five million Filipinos owning a cell phone by 2001. Because of the highly social nature of Philippine culture and the affordability of SMS compared to voice calls, SMS usage shot up. Filipinos used texting not only for social messages but also for political purposes, as it allowed the Filipinos to express their opinions on current events and political issues. It became a powerful tool for Filipinos in promoting or denouncing issues and was a key factor during the 2001 EDSA II revolution, which overthrew then-President Joseph Estrada, who was eventually found guilty of corruption. According to 2009 statistics, there were about 72 million mobile service subscriptions (roughly 80% of the Filipino population), with around 1.39 billion SMS messages being sent daily. Because of the large number of text messages being sent, the Philippines became known as the "text capital of the world" during the late 1990s until the early 2000s.

New Zealand

There are three mobile network companies operating in New Zealand, with some sub-brands and MVNOs. Spark NZ (formerly Telecom NZ), was the first telecommunication company in New Zealand. In 2011, Spark was broken into two companies by regulation, with Chorus Ltd taking the landline infrastructure and Spark NZ providing services including over their mobile network. Vodafone NZ (now One NZ) acquired mobile network provider Bellsouth New Zealand in 1998 and had 2.32 million customers as of July 2013. Vodafone launched the first Text messaging service in 1999 and has introduced innovative TXT services like SafeTXT and CallMe 2degrees Mobile Ltd launched in August 2009. In 2005, around 85% of the adult population had a mobile phone. In general, texting is more popular than making phone calls, as it is viewed as less intrusive and therefore more polite.

Sub-Saharan Africa

In 2009, it was predicted that text messaging would become a key revenue driver for mobile network operators in Africa over the following couple of years. Today, text messaging is already slowly gaining influence in the African market. One such person used text messaging to spread the word about HIV and AIDS. In September 2009, a multi-country campaign in Africa used text messaging to expose stock-outs of essential medicines at public health facilities and put pressure on governments to address the issue.

Social effects

The advent of text messaging made possible new forms of interaction that were not possible before. A person could carry out a conversation with another user without the constraint of being expected to reply within a short amount of time and without needing to set time aside to engage in conversation. With voice calling, both participants need to be free at the same time. Mobile phone users can maintain communication during situations in which a voice call is impractical, impossible, or unacceptable, such as during a school class or work meeting. Texting has provided a venue for participatory culture, allowing viewers to vote in online and TV polls, as well as receive information while they are on the move. Texting can also bring people together and create a sense of community through "Smart Mobs" or "Net War", which create "people power". Research in 2015 has also proven that text messaging is somehow making the social distances larger and could be ruining verbal communication skills for many people.

Effect on language

Main article: SMS language

The small phone keypad and the rapidity of typical text message exchanges have caused a number of spelling abbreviations: as in the phrase "txt msg", "u" (an abbreviation for "you"), "HMU"("hit me up"; i.e., call me), or use of camel case, such as in "ThisIsVeryLame". To avoid the even more limited message lengths allowed when using Cyrillic or Greek letters, speakers of languages written in those alphabets often use the Latin alphabet for their own language. In certain languages utilizing diacritic marks, such as Polish, SMS technology created an entire new variant of written language: characters normally written with diacritic marks (e.g., ą, ę, ś, ż in Polish) are now being written without them (as a, e, s, z) to enable using cell phones without Polish script or to save space in Unicode messages. Historically, this language developed out of shorthand used in bulletin board systems and later in Internet chat rooms, where users would abbreviate some words to allow a response to be typed more quickly, though the amount of time saved was often inconsequential. However, this became much more pronounced in SMS, where mobile phone users either have a numeric keyboard (with older cellphones) or a small QWERTY keyboard (for 2010s-era smartphones), so more effort is required to type each character, and there is sometimes a limit on the number of characters that may be sent. In Mandarin Chinese, numbers that sound similar to words are used in place of those words. For example, the numbers 520 in Chinese (wǔ èr líng) sound like the words for "I love you" (wǒ ài nǐ). The sequence 748 (qī sì bā) sounds like the curse "go to hell" (qù sǐ ba).

Predictive text software, which attempts to guess words (Tegic's T9 as well as iTap) or letters (Eatoni's LetterWise) reduces the labour of time-consuming input. This makes abbreviations not only less necessary but slower to type than regular words that are in the software's dictionary. However, it makes the messages longer, often requiring the text message to be sent in multiple parts and, therefore, costing more to send. The use of text messaging has changed the way that people talk and write essays, some believing it to be harmful. Children today are receiving cell phones at an age as young as eight years old; more than 35 per cent of children in second and third grade have their own mobile phones. Because of this, the texting language is integrated into the way that students think from an earlier age than ever before. In November 2006, New Zealand Qualifications Authority approved the move that allowed students of secondary schools to use mobile phone text language in the end-of-the-year-exam papers. Highly publicized reports, beginning in 2002, of the use of text language in school assignments, caused some to become concerned that the quality of written communication is on the decline, and other reports claim that teachers and professors are beginning to have a hard time controlling the problem. However, the notion that text language is widespread or harmful is refuted by research from linguistic experts.

An article in The New Yorker explores how text messaging has anglicized some of the world's languages. The use of diacritic marks is dropped in languages such as French, as well as symbols in Ethiopian languages. In his book, Txtng: the Gr8 Db8 (which translates as "Texting: the Great Debate"), David Crystal states that texters in all eleven languages use "lol" ("laughing out loud"), "u", "brb" ("be right back"), and "gr8" ("great"), all English-based shorthands. The use of pictograms and logograms in texts are present in every language. They shorten words by using symbols to represent the word or symbols whose name sounds like a syllable of the word such as in 2day or b4. This is commonly used in other languages as well. Crystal gives some examples in several languages such as Italian sei, "six", is used for sei, "you are". Example: dv6 = dove sei ("where are you") and French k7 = cassette ("cassette tape"). There is also the use of numeral sequences, substituting for several syllables of a word and creating whole phrases using numerals. For example, in French, a12c4 can be said as à un de ces quatres, "see you around" (literally: "to one of these four "). An example of using symbols in texting and borrowing from English is the use of @. Whenever it is used in texting, its intended use is with the English pronunciation. Crystal gives the example of the Welsh use of @ in @F, pronounced ataf, meaning "to me". In character-based languages such as Chinese and Japanese, numbers are assigned syllables based on the shortened form of the pronunciation of the number, sometimes the English pronunciation of the number. In this way, numbers alone can be used to communicate whole passages, such as in Chinese, "8807701314520" (bào bao nǐ qīng qing nǐ yīshēng yìshì wǒ ài nǐ) can be literally translated as "Hug hug you, kiss you, whole life, whole life I love you." English influences worldwide texting in variation, but still in combination with the individual properties of languages.

American popular culture is also recognized in shorthand. For example, Homer Simpson translates into: ~(_8^(|). Crystal also suggests that texting has led to more creativity in the English language, giving people opportunities to create their own slang, emoticons, abbreviations, acronyms, etc. The feeling of individualism and freedom makes texting more popular and a more efficient way to communicate. Crystal has also been quoted in saying that "In a logical world, text messaging should not have survived." But text messaging didn't just come out of nowhere. It originally began as a messaging system that would send out emergency information. But it gained immediate popularity with the public. What followed is the SMS we see today, which is a very quick and efficient way of sharing information from person to person. Work by Richard Ling has shown that texting has a gendered dimension and it plays into the development of teen identity. In addition we text to a very small number of other persons. For most people, half of their texts go to 3 – 5 other people.

Research by Rosen et al. (2009) found that those young adults who used more language-based textisms (shortcuts such as LOL, 2nite, etc.) in daily writing produced worse formal writing than those young adults who used fewer linguistic textisms in daily writing. However, the exact opposite was true for informal writing. This suggests that perhaps the act of using textisms to shorten communication words leads young adults to produce more informal writing, which may then help them to be better "informal" writers. Due to text messaging, teens are writing more, and some teachers see that this comfort with language can be harnessed to make better writers. This new form of communication may be encouraging students to put their thoughts and feelings into words and this may be able to be used as a bridge, to get them more interested in formal writing.

Joan H. Lee in her thesis, What does txting do 2 language: The influences of exposure to messaging and print media on acceptability constraints (2011), she associates exposure to text messaging with more rigid acceptability constraints. The thesis suggests that more exposure to the colloquial, Generation Text language of text messaging contributes to being less accepting of words. In contrast, Lee found that students with more exposure to traditional print media (such as books and magazines) were more accepting of both real and fictitious words. The thesis, which garnered international media attention, also presents a literature review of academic literature on the effects of text messaging on language. Texting has also been shown to have had no effect or some positive effects on literacy. According to Plester, Wood and Joshi and their research done on the study of 88 British 10–12-year-old children and their knowledge of text messages, "textisms are essentially forms of phonetic abbreviation" that show that "to produce and read such abbreviations arguably requires a level of phonological awareness (and orthographic awareness) in the child concerned".

Texting while driving

Main article: Texting while driving

Texting while driving leads to increased distraction behind the wheel and can lead to an increased risk of an accident. In 2006, Liberty Mutual Insurance Group conducted a survey with more than 900 teens from over 26 high schools nationwide. The results showed that 87% of students found texting to be "very" or "extremely" distracting. A study by AAA found that 46% of teens admitted to being distracted behind the wheel due to texting. One example of distraction behind the wheel is the 2008 Chatsworth train collision, which killed 25 passengers. The engineer had sent 45 text messages while operating the train. A 2009 experiment with Car and Driver editor Eddie Alterman (that took place at a deserted airfield, for safety reasons) compared texting with drunk driving. The experiment found that texting while driving was more dangerous than being drunk. While being legally drunk added 4 feet to Alterman's stopping distance while going 70 mph (110 km/h), reading an e-mail on a phone added 36 feet (11 m), and sending a text message added 70 feet (21 m).

In 2009, the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute released the results of an 18-month study that involved placing cameras inside the cabs of more than 100 long-haul trucks, which recorded the drivers over a combined driving distance of three million miles. The study concluded that when the drivers were texting, their risk of crashing was 23 times greater than when not texting.

Texting while walking

Due to the proliferation of smart phone applications performed while walking, "texting while walking" or "wexting" is the increasing practice of people being transfixed to their mobile device without looking in any direction but their personal screen while walking. First coined reference in 2015 in New York from Rentrak's chief client officer when discussing time spent with media and various media usage metrics. Text messaging among pedestrians leads to increased cognitive distraction and reduced situation awareness, and may lead to increases in unsafe behaviour leading to injury and death. Recent studies conducted on cell phone use while walking showed that cell phone users recall fewer objects when conversing, walk slower, have altered gait and are more unsafe when crossing a street. Additionally, some gait analyses showed that stance phase during overstepping motion, longitudinal and lateral deviation increased during cell phone operation, but step length and clearance did not; a different analysis did find increased step clearance and reduced step length.

It is unclear which processes may be affected by distraction, which types of distraction may affect which cognitive processes, and how individual differences may affect the influence of distraction. Lamberg and Muratori believe that engaging in a dual-task, such as texting while walking, may interfere with working memory and result in walking errors. Their study demonstrated that participants engaged in text messaging were unable to maintain walking speed or retain accurate spatial information, suggesting an inability to adequately divide their attention between two tasks. According to them, the addition of texting while walking with vision occluded increases the demands placed on the working memory system resulting in gait disruptions.

Texting on a phone distracts participants, even when the texting task used is a relatively simple one. Stavrinos et al. investigated the effect of other cognitive tasks, such as engaging in conversations or cognitive tasks on a phone, and found that participants actually have reduced visual awareness. This finding was supported by Licence et al., who conducted a similar study. For example, texting pedestrians may fail to notice unusual events in their environment, such as a unicycling clown. These findings suggest that tasks that require the allocation of cognitive resources can affect visual attention even when the task itself does not require the participants to avert their eyes from their environment. The act of texting itself seems to impair pedestrians' visual awareness. It appears that the distraction produced by texting is a combination of both a cognitive and visual perceptual distraction. A study conducted by Licence et al. supported some of these findings, particularly that those who text while walking significantly alter their gait. However, they also found that the gait pattern texters adopted was slower and more "protective", and consequently did not increase obstacle contact or tripping in a typical pedestrian context.

There have also been technological approaches to increase the safety/awareness of pedestrians that are (unintentionally) blind while using a smartphone, e.g., using a Kinect or an ultrasound phone cover as a virtual white cane, or using the built-in camera to algorithmically analyze single, respectively a stream of pictures for obstacles, with Wang et al. proposing to use machine learning to specifically detect incoming vehicles.

Sexting

Main article: SextingSexting is slang for the act of sending sexually explicit or suggestive content between mobile devices using SMS. It contains either text, images, or video that is intended to be sexually arousing. Sexting was reported as early as 2005 in The Sunday Telegraph Magazine, constituting a trend in the creative use of SMS to excite another with alluring messages throughout the day.

Although sexting often takes place consensually between two people, it can also occur against the wishes of a person who is the subject of the content. A number of instances have been reported in which the recipients of sexting have shared the content of the messages with others, with less intimate intentions, such as to impress their friends or embarrass their sender. Celebrities such as Miley Cyrus, Vanessa Hudgens, and Adrienne Bailon have been victims of such abuses of sexting.

A 2008 survey by The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy and CosmoGirl.com suggested a trend of sexting and other seductive online content being readily shared between teens. One in five teen girls surveyed (22 per cent)—and 11 per cent of teen girls aged 13–16 years old—say they have electronically sent, or posted online, nude or semi-nude images of themselves. One-third (33 per cent) of teen boys and one-quarter (25 per cent) of teen girls say they were shown private nude or semi-nude images. According to the survey, sexually suggestive messages (text, e-mail, and instant messaging) were even more common than images, with 39 per cent of teens having sent or posted such messages, and half of the teens (50 per cent) having received them.

A 2012 study that has received wide international media attention was conducted at the University of Utah Department of Psychology by Donald S. Strassberg, Ryan Kelly McKinnon, Michael Sustaíta and Jordan Rullo. They surveyed 606 teenagers ages 14–18 and found that nearly 20 per cent of the students said they had sent a sexually explicit image of themselves via cell phone, and nearly twice as many said that they had received a sexually explicit picture. Of those receiving such a picture, over 25 per cent indicated that they had forwarded it to others. In addition, of those who had sent a sexually explicit picture, over a third had done so despite believing that there could be serious legal and other consequences if they got caught. Students who had sent a picture by cell phone were more likely than others to find the activity acceptable. The authors conclude: "These results argue for educational efforts such as cell phone safety assemblies, awareness days, integration into class curriculum and teacher training, designed to raise awareness about the potential consequences of sexting among young people." Sexting becomes a legal issue when teens (under 18) are involved, because any nude photos they may send of themselves would put the recipients in possession of child pornography.

In schools

Text messaging has affected students academically by creating an easier way to cheat on exams. In December 2002, a dozen students were caught cheating on an accounting exam through the use of text messages on their mobile phones. In December 2002, Hitotsubashi University in Japan failed 26 students for receiving emailed exam answers on their mobile phones. The number of students caught using mobile phones to cheat on exams has increased significantly in recent years. According to Okada (2005), most Japanese mobile phones can send and receive long text messages of between 250 and 3000 characters with graphics, video, audio, and Web links.

In England, 287 school and college students were excluded from exams in 2004 for using mobile phones during exams. Some teachers and professors claim that advanced texting features can lead to students cheating on exams. Students in high school and college classrooms are using their mobile phones to send and receive texts during lectures at high rates. Further, published research has established that students who text during college lectures have impaired memories of the lecture material compared to students who do not. For example, in one study, the number of irrelevant text messages sent and received during a lecture covering the topic of developmental psychology was related to students' memory of the lecture.

Bullying

Main article: CyberbullyingSpreading rumors and gossip by text message, using text messages to bully individuals, or forwarding texts that contain defamatory content is an issue of great concern for parents and schools. Text "bullying" of this sort can cause distress and damage reputations. In some cases, individuals who are bullied online have committed suicide. Harding and Rosenberg (2005) argue that the urge to forward text messages can be difficult to resist, describing text messages as "loaded weapons".

Apple's messaging app, Messages, uses Apple's Internet-based messaging service, iMessage, to send messages to other iMessage users, and uses SMS as a fallback when no data connection is present, or when messaging non-iMessage users. It sets the color of messages depending on which technology was used. This has led to instances of iMessage users bullying people without iPhones.

Influence on perceptions of the student

When a student sends an email that contains phonetic abbreviations and acronyms that are common in text messaging (e.g., "gr8" instead of "great"), it can influence how that student is subsequently evaluated. In a study by Lewandowski and Harrington (2006), participants read a student's email sent to a professor that either contained text-messaging abbreviations (gr8, How R U?) or parallel text in standard English (great, How are you?), and then provided impressions of the sender. Students who used abbreviations in their email were perceived as having a less favorable personality and as putting forth less effort on an essay they submitted along with the email. Specifically, abbreviation users were seen as less intelligent, responsible, motivated, studious, dependable, and hard-working. These findings suggest that the nature of a student's email communication can influence how others perceive the student and their work.

However, students have become aware of the reality that using these textisms and adaptations can negatively impact their professionalism. Drouin and Davis surveyed American undergraduates in 2009 and found that three quarters of participants believed the use of textisms were not appropriate in formal messaging and writing. A study performed by Grace et al. (2013) asked 150 undergraduate students to rate the appropriateness of using textisms in a given scenario on a scale of one to five – five being entirely appropriate and one being not at all. All but eleven of the students rated the use of textisms in exams and typed assignments as "not at all appropriate", showing that the students are aware of how they must adapt their written language and tone depending on the context. Grace et al. (2010) went further, observing hundreds of academic papers from previous undergraduate students' exams, only to find that out of 533,500 words, a mere 0.02% were textisms. They owe this to the fact that the more accumulated experience a student has, the more they are able to understand when the "appropriate" and "inappropriate" times to use such language is.

Law and crime

Text messaging has been a subject of interest for police forces around the world. One of the issues of concern to law enforcement agencies is the use of encrypted text messages. In 2003, a British company developed a program called Fortress SMS which used 128 bit AES encryption to protect SMS messages. Police have also retrieved deleted text messages to aid them in solving crimes. For example, Swedish police retrieved deleted texts from a cult member who claimed she committed a double murder based on forwarded texts she received. Police in Tilburg, Netherlands, started an SMS alert program, in which they would send a message to ask citizens to be vigilant when a burglar was on the loose or a child was missing in their neighbourhood. Several thieves have been caught and children have been found using the SMS Alerts. The service has been expanding to other cities. A Malaysian–Australian company has released a multi-layer SMS security program. Boston police are now turning to text messaging to help stop crime. The Boston Police Department asks citizens to send texts to make anonymous crime tips.

Under some interpretations of sharia law, husbands can divorce their wives by the pronouncement of talaq. In 2003, a court in Malaysia upheld such a divorce pronouncement which was transmitted via SMS.

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in 2017 that under the state constitution, police require a warrant before obtaining access to text messages without consent.

Social unrest

Texting has been used on a number of occasions with the result of the gathering of large aggressive crowds. SMS messaging drew a crowd to Cronulla Beach in Sydney resulting in the 2005 Cronulla riots. Not only were text messages circulating in the Sydney area but in other states as well (Daily Telegraph). The volume of such text messages and e-mails also increased in the wake of the riot. The crowd of 5,000 at stages became violent, attacking certain ethnic groups. Sutherland Shire Mayor directly blamed heavily circulated SMS messages for the unrest. NSW police considered whether people could be charged over the texting. Retaliatory attacks also used SMS.

The Narre Warren Incident, when a group of 500 party goers attended a party at Narre Warren in Melbourne, Australia, and rioted in January 2008, also was a response of communication being spread by SMS and Myspace. Following the incident, the Police Commissioner wrote an open letter asking young people to be aware of the power of SMS and the Internet. In Hong Kong, government officials find that text messaging helps socially because they can send multiple texts to the community. Officials say it is an easy way of contacting the community or individuals for meetings or events. Texting was used to coordinate gatherings during the 2009 Iranian election protests.

Between 2009 and 2012 the U.S. secretly created and funded a Twitter-like service for Cubans called ZunZuneo, initially based on mobile phone text message service and later with an internet interface. The service was funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development through its Office of Transition Initiatives, who utilized contractors and front companies in the Cayman Islands, Spain and Ireland. A longer-term objective was to organize "smart mobs" that might "renegotiate the balance of power between the state and society." A database about the subscribers was created, including gender, age, and "political tendencies". At its peak ZunZuneo had 40,000 Cuban users, but the service closed as financially unsustainable when U.S. funding was stopped.

In politics

See also: Political text messaging

Text messaging has affected the political world. American campaigns find that text messaging is a much easier, cheaper way of getting to the voters than the door-to-door approach. In 2006 Mexico's then president-elect Felipe Calderón launched millions of text messages in the days immediately preceding his narrow win over Andrés Manuel López Obrador. In January 2001, Joseph Estrada was forced to resign from the post of president of the Philippines. The popular campaign against him was widely reported to have been coordinated with SMS chain letters. A massive texting campaign was credited with boosting youth turnout in Spain's 2004 parliamentary elections. In 2008, Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick and his Chief of Staff at the time became entangled in a sex scandal stemming from the exchange of over 14,000 text messages that eventually led to his forced resignation, the conviction of perjury, and other charges. Text messaging has been used to turn down other political leaders. During the 2004 U.S. Democratic and Republican National Conventions, protesters used an SMS-based organizing tool called TXTmob to get to opponents. In the last day before the 2004 presidential elections in Romania, a message against Adrian Năstase was largely circulated, thus breaking the laws that prohibited campaigning that day. Text messaging has helped politics by promoting campaigns.

On 20 January 2001, President Joseph Estrada of the Philippines became the first head of state in history to lose power to a smart mob. More than one million Manila residents assembled at the site of the 1986 People Power peaceful demonstrations that have toppled the Marcos regime. These people have organized themselves and coordinated their actions through text messaging. They were able to bring down a government without having to use any weapons or violence. Through text messaging, their plans and ideas were communicated to others and successfully implemented. Also, this move encouraged the military to withdraw their support from the regime, and as a result, the Estrada government fell. People were able to converge and unite with the use of their cell phones. "The rapid assembly of the anti-Estrada crowd was a hallmark of early smart mob technology, and the millions of text messages exchanged by the demonstrators in 2001 was, by all accounts, a key to the crowds esprit de corps."

Use in healthcare

Text messaging is a rapidly growing trend in Healthcare. A randomized controlled trial of text messaging intervention for diabetes in Bangladesh was one of the first robust trials to report improvement in diabetes management in a low-and-middle income country. A recent systematic review and individual participants data meta analysis from 3,779 participants reported that mobile phone text messaging could improve blood pressure and body mass index. Another study in people with type 2 diabetes showed that participants were willing to pay a modest amount to receive a diabetes text messaging program in addition to standard care. "One survey found that 73% of physicians text other physicians about work- similar to the overall percentage of the population that texts." A 2006 study of reminder messages sent to children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus showed favorable changes in adherence to treatment. A risk is that these physicians could be violating the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Where messages could be saved to a phone indefinitely, patient information could be subject to theft or loss, and could be seen by other unauthorized persons. The HIPAA privacy rule requires that any text message involving a medical decision must be available for the patient to access, meaning that any texts that are not documented in an EMR system could be a HIPAA violation.

Medical concerns

Main article: BlackBerry thumbThe excessive use of the thumb for pressing keys on mobile devices has led to a high rate of a form of repetitive strain injury termed "BlackBerry thumb" (although this refers to strain developed on older Blackberry devices, which had a scroll wheel on the side of the phone). An inflammation of the tendons in the thumb caused by constant text-messaging is also called text-messager's thumb, or texting tenosynovitis. Texting has also been linked as a secondary source in numerous traffic collisions, in which police investigations of mobile phone records have found that many drivers have lost control of their cars while attempting to send or retrieve a text message. Increasing cases of Internet addiction are now also being linked to text messaging, as mobile phones are now more likely to have e-mail and Web capabilities to complement the ability to text.

Etiquette

Texting etiquette refers to what is considered appropriate texting behaviour. These expectations may concern different areas, such as the context in which a text was sent and received/read, who each participant was with when the participant sent or received/read a text message or what constitutes impolite text messages. At the website of The Emily Post Institute, the topic of texting has spurred several articles with the "do's and dont's" regarding the new form of communication. One example from the site is: "Keep your message brief. No one wants to have an entire conversation with you by texting when you could just call him or her instead." Another example is: "Don't use all Caps. Typing a text message in all capital letters will appear as though you are shouting at the recipient, and should be avoided."

Expectations for etiquette may differ depending on various factors. For example, expectations for appropriate behaviour have been found to differ markedly between the U.S. and India. Another example is generational differences. In The M-Factor: How the Millennial Generation Is Rocking the Workplace, Lynne Lancaster and David Stillman note that younger Americans often do not consider it rude to answer their cell or begin texting in the middle of a face-to-face conversation with someone else, while older people, less used to the behavior and the accompanying lack of eye contact or attention, find this to be disruptive and ill-mannered. With regard to texting in the workplace, Plantronics studied how we communicate at work] and found that 58% of US knowledge workers have increased the use of text messaging for work in the past five years. The same study found that 33% of knowledge workers felt text messaging was critical or very important to success and productivity at work.

Typing awareness indicators

In some text messaging software products, an ellipsis is displayed while the interlocutor is typing characters. The feature has been referred to as a "typing awareness indicator", for which patents have been filed since the 1990s.

Challenges

Spam

Further information: Mobile phone spamIn 2002, an increasing trend towards spamming mobile phone users through SMS prompted cellular-service carriers to take steps against the practice, before it became a widespread problem. No major spamming incidents involving SMS had been reported as of March 2007, but the existence of mobile phone spam has been noted by industry watchdogs including Consumer Reports magazine and the Utility Consumers' Action Network (UCAN). In 2005, UCAN brought a case against Sprint for spamming its customers and charging $0.10 per text message. The case was settled in 2006 with Sprint agreeing not to send customers Sprint advertisements via SMS. SMS expert Acision (formerly LogicaCMG Telecoms) reported a new type of SMS malice at the end of 2006, noting the first instances of SMiShing (a cousin to e-mail phishing scams). In SMiShing, users receive SMS messages posing to be from a company, enticing users to phone premium-rate numbers or reply with personal information. Similar concerns were reported by PhonepayPlus, a consumer watchdog in the United Kingdom, in 2012.

Pricing concerns

Concerns have been voiced over the excessive cost of off-plan text messaging in the United States. AT&T Mobility, along with most other service providers, charges texters 20 cents per message if they do not have a messaging plan or if they have exceeded their allotted number of texts. Given that an SMS message is at most 160 bytes in size, this cost scales to a cost of $1,310 per megabyte sent via text message. This is in sharp contrast with the price of unlimited data plans offered by the same carriers, which allow the transmission of hundreds of megabytes of data for monthly prices of about $15 to $45 in addition to a voice plan. As a comparison, a one-minute phone call uses up the same amount of network capacity as 600 text messages, meaning that if the same cost-per-traffic formula were applied to phone calls, cell phone calls would cost $120 per minute. With service providers gaining more customers and expanding their capacity, their overhead costs should be decreasing, not increasing. In 2005, text messaging generated nearly 70 billion dollars in revenue, as reported by Gartner, industry analysts, three times as much as Hollywood box office sales in 2005. World figures showed that over a trillion text messages were sent in 2005.

Although major cellphone providers deny any collusion, fees for out-of-package text messages have increased, doubling from 10 to 20 cents in the United States between 2007 and 2008 alone. On 16 July 2009, Senate hearings were held to look into any breach of the Sherman Antitrust Act. The same trend is visible in other countries, though increasingly widespread flat-rate plans, for example in Germany, do make text messaging easier, text messages sent abroad still result in higher costs.

Increasing competition

While text messaging is still a growing market, traditional SMS is becoming increasingly challenged by alternative messaging services which are available on smartphones with data connections. These services are much cheaper and offer more functionality like exchanging multimedia content (e.g. photos, videos or audio notes) and group messaging. Especially in western countries some of these services attract more and more users. Prominent examples of these include Apple's iMessage (exclusive to the Apple ecosystem) and the GSMA's RCS.

In 2021, 8.4 trillion SMS messages were sent globally, compared to 18.25 trillion for WhatsApp alone.

Security concerns

Experts have advised business users not to use consumer SMS for confidential communication. The contents of common SMS messages are known to the network operator's systems and personnel. Therefore, consumer SMS is not an appropriate technology for secure communications. To address this issue, many companies use an SMS gateway provider based on SS7 connectivity to route the messages. The advantage of this international termination model is the ability to route data directly through SS7, which gives the provider visibility of the complete path of the SMS. This means SMS messages can be sent directly to and from recipients without having to go through the SMS-C of other mobile operators. This approach reduces the number of mobile operators that handle the message; however, experts have advised not to consider it as an end-to-end secure communication, as the content of the message is exposed to the SMS gateway provider.

An alternative approach is to use end-to-end security software that runs on both the sending and receiving device, where the original text message is transmitted in encrypted form as a consumer SMS. By using key rotation, the encrypted text messages stored under data retention laws at the network operator cannot be decrypted even if one of the devices is compromised. A problem with this approach is that communicating devices needs to run compatible software. Failure rates without backward notification can be high between carriers. International texting can be unreliable depending on the country of origin, destination and respective operators. Differences in the character sets used for coding can cause a text message sent from one country to another to become unreadable.

In popular culture

Records and competition

The Guinness Book of World Records has a world record for text messaging, currently held by Sonja Kristiansen of Norway. Kristiansen keyed in the official text message, as established by Guinness, in 37.28 seconds. The message is, "The razor-toothed piranhas of the genera Serrasalmus and Pygocentrus are the most ferocious freshwater fish in the world. In reality, they seldom attack a human." In 2005, the record was held by a 24-year-old Scottish man, Craig Crosbie, who completed the same message in 48 seconds, beating the previous time by 19 seconds. The Book of Alternative Records lists Chris Young of Salem, Oregon as the world-record holder for the fastest 160-character text message where the contents of the message are not provided ahead of time. His record of 62.3 seconds was set on 23 May 2007.

Elliot Nicholls of Dunedin, New Zealand currently holds the world record for the fastest blindfolded text messaging. A record of a 160-letter text in 45 seconds while blindfolded was set on 17 November 2007, beating the old record of 1-minute 26 seconds set by an Italian in September 2006. Andrew Acklin of Ohio is credited with the world record for most text messages sent or received in a single month, with 200,052. His accomplishments were first in the World Records Academy and later followed up by Ripley's Believe It Or Not 2010: Seeing Is Believing. He has been acknowledged by The Universal Records Database for the most text messages in a single month; however, this has since been broken twice and as of 2010 was listed as 566607 messages by Fred Lindgren.

In January 2010, LG Electronics sponsored an international competition, the LG Mobile World Cup, to determine the fastest pair of texters. The winners were a team from South Korea, Ha Mok-min and Bae Yeong-ho. On 6 April 2011, SKH Apps released an iPhone app, iTextFast, to allow consumers to test their texting speed and practice the paragraph used by Guinness Book of World Records. As of 2011, best time listed on Game Center for that paragraph is 34.65 seconds.

Morse code

A few competitions have been held between expert Morse code operators and expert SMS users. Several mobile phones have Morse code ring tones and alert messages. For example, many Nokia mobile phones have an option to beep "S M S" in Morse code when it receives a short message. Some of these phones could also play the Nokia slogan "Connecting people" in Morse code as a message tone. There are third-party applications available for some mobile phones that allow Morse input for short messages.

Tattle texting

"Tattle texting" can mean either of two different texting trends:

Arena security

Many sports arenas now offer a number where patrons can text report security concerns, like drunk or unruly fans, or safety issues like spills. These programs have been praised by patrons and security personnel as more effective than traditional methods. For instance, the patron doesn't need to leave his seat and miss the event in order to report something important. Also, disruptive fans can be reported with relative anonymity. "Text tattling" also gives security personnel a useful tool to prioritize messages. For instance, a single complaint in one section about an unruly fan can be addressed when convenient, while multiple complaints by several different patrons can be acted upon immediately.

Smart cars

In this context, "tattle texting" refers to an automatic text sent by the computer in an automobile, because a preset condition was met. The most common use for this is for parents to receive texts from the car their child is driving, alerting them to speeding or other issues. Employers can also use the service to monitor their corporate vehicles. The technology is still new and (currently) only available on a few car models.

Common conditions that can be chosen to send a text are:

- Speeding. With the use of GPS, stored maps, and speed limit information, the onboard computer can determine if the driver is exceeding the current speed limit. The device can store this information and/or send it to another recipient.

- Range. Parents/employers can set a maximum range from a fixed location after which a "tattle text" is sent. Not only can this keep children close to home and keep employees from using corporate vehicles inappropriately, but it can also be a crucial tool for quickly identifying stolen vehicles, car jackings, and kidnappings.

See also

- Instant messaging

- Personal message, also called private message or direct message

- Messaging apps

- Chat language

- Enhanced Messaging Service

- Mobile dial code

- Operator messaging

- Telegram

- Tironian notes, scribal abbreviations and ligatures: Roman and medieval abbreviations used to save space on manuscripts and epigraphs

- Comparison of user features of messaging platforms

Further reading

- Al-Kadi̇, Abdu (17 June 2019). "A Cross-Sectional Study of Textese in Academic Writing: Magnitude of Penetration, Impacts, and Perceptions". International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research. 6 (1): 29–39. doi:10.33200/ijcer.534692. S2CID 195794891.

- Rosen, Larry D.; Chang, Jennifer; Erwin, Lynne; Carrier, L. Mark; Cheever, Nancy A. (June 2010). "The Relationship Between "Textisms" and Formal and Informal Writing Among Young Adults". Communication Research. 37 (3): 420–440. doi:10.1177/0093650210362465. ISSN 0093-6502. S2CID 46309911.

- Cingel, Drew P.; Sundar, S. Shyam (December 2012). "Texting, techspeak, and tweens: The relationship between text messaging and English grammar skills". New Media & Society. 14 (8): 1304–1320. doi:10.1177/1461444812442927. ISSN 1461-4448. S2CID 5469636.

- Wood, Clare; Kemp, Nenagh; Waldron, Sam (November 2014). "Exploring the longitudinal relationships between the use of grammar in text messaging and performance on grammatical tasks". British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 32 (4): 415–429. doi:10.1111/bjdp.12049. ISSN 0261-510X. PMC 4265847. PMID 24923868.

- Sadiq, Uzma; Ajmal, Muhammad; Suleman, Nazia (2022). "mpact of text messaging on students' writing skills at university level: a corpus based analysis". Competitive Social Sciences Research Journal. 3 (1): 194–201.

References

- "Europe, Asia embrace GR8 way to stay in touch". NBC News. 23 April 2004. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- Shannon, Victoria (5 December 2007). "15 years of text messages, a 'cultural phenomenon'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- "IT in everyday life: View as single page | OpenLearn". www.open.edu. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- Wakeford, N. (1 January 2003). "A Social History of the Mobile Telephone with a View of its Future". Bt Technology Journal.

- Morris, Robert; Pinchot, Jamie (2010). "Conference on Information Systems Applied Research" (PDF). How Mobile Technology is Changing Our Culture. 3: 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2017 – via CONISAR.

-

"Fifty years of telex". Telecommunication Journal. 51: 35. 1984. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

Just over fifty years ago, in October 1933, the Deutsche Reichspost as it was then known, opened the world's first public teleprinter network.

- Herbst, Kris; Ubois, Jeff (14 November 1988). "The competition". Network World. Vol. 5. IDG Network World Inc. p. 68. ISSN 0887-7661. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

Telex originated in Germany and rapidly expanded to other countries after World War II.

- "The Text Message Turns 20: A Brief History of SMS". theweek.com. 3 December 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

1984 Sitting at a typewriter at his home in Bonn, Germany, Friedhelm Hillebrand types random sentences and questions, counting every letter, number, and space. Almost every time, the messages amount to fewer than 160 characters — what would become the limit of early text messages — and thus the concept for the perfect-length, rapid-fire 'short message' was born.

- GSM document 19/85, available on the GSM-SMG Archive DVD-ROM

- Hillebrand, ed. (2010). Short Message Service, the Creation of Personal Global Text Messaging. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-68865-6.

- ITU-T, ed. (1993). Introduction to CCITT Signalling System No. 7. ITU.

- Ariel Bogle (3 December 2017). "It's been 25 years since the first-ever text message and the kids are alright". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Shannon, Victoria (5 December 2007). "15 years of text messages, a 'cultural phenomenon'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2010.