In quantum computing, the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) is a quantum algorithm for quantum chemistry, quantum simulations and optimization problems. It is a hybrid algorithm that uses both classical computers and quantum computers to find the ground state of a given physical system. Given a guess or ansatz, the quantum processor calculates the expectation value of the system with respect to an observable, often the Hamiltonian, and a classical optimizer is used to improve the guess. The algorithm is based on the variational method of quantum mechanics.

It was originally proposed in 2014, with corresponding authors Alberto Peruzzo, Alán Aspuru-Guzik and Jeremy O'Brien. The algorithm has also found applications in quantum machine learning and has been further substantiated by general hybrid algorithms between quantum and classical computers. It is an example of a noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) algorithm.

Description

Pauli encoding

The objective of the VQE is to find a set of quantum operations that prepares the lowest energy state (or minima) of a close approximation to some target quantity or observable. While the only strict requirement for the representation of an observable is its efficiency in estimating its expectation values, it is often more straightforward if the operator has a compact or simple expression in terms of Pauli operators or tensor products of Pauli operators.

For a fermionic system, it is often most convenient to qubitize: that is to write the many-body Hamiltonian of the system using second quantization, and then use a mapping to write the creation-annihiliation operators in terms of Pauli operators. Common schemes for fermions include Jordan–Wigner transformation, Bravyi–Kitaev transformation, and parity transformation.

Once the Hamiltonian is written in terms of Pauli operators and irrelevant states are discarded (finite-dimensional space), it would consist of a linear combination of Pauli strings consisting of tensor products of Pauli operators (for example ), such that

- ,

where are numerical coefficients. Based on the coefficients, the number of Pauli strings can be reduced in order to optimize the calculation.

The VQE can be adapted to other optimization problems by adapting the Hamiltonian to be a cost function.

Ansatz and initial trial function

The choice of ansatz state depends on the system of interest. In gate-based quantum computing, the ansatz is given by a parametrized quantum circuit, whose parameters can be updated after each run. The ansatz has to be adaptable enough to not miss the desired state. A common method to obtain a valid ansatz is given by the unitary coupled cluster (UCC) framework and its extensions.

If the ansatz is not chosen adequately the procedure may halt at suboptimal parameters that do not correspond to a minima. In this situation, the algorithm is said to have reached a 'barren plateau'.

The ansatz can be set to an initial trial function to start the algorithm. For example, for a molecular system, one can use the Hartree–Fock method to provide a starting state that is close to the real ground state.

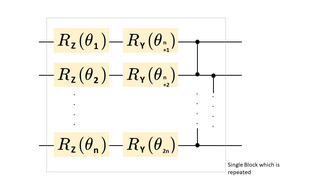

Another variant of the ansatz circuit is the hardware efficient ansatz, which consists of sequence of 1 qubit rotational gates and 2 qubit entangling gates. The number of repetitions of 1-qubit rotational gates and 2-qubit entangling gates is called the depth of the circuit.

Measurement

The expectation value of a given state with parameters , has an expectation value of the energy or cost function given by

so in order to obtain the expectation value of the energy, one can measure the expectation value of each Pauli string (number of counts for a given value over the total number of counts). This step corresponds to measuring each qubit in the axis provided by the Pauli string. For example, for the string , the first qubit is to be measured in the x-axis, while the last two are to be measured in the y-axis of the Bloch sphere. If measurement in the z-axis is only possible, then Clifford gates can be used to transform between axes. If two Pauli strings commute, then they can be both measured simultaneously using the same circuit and interpreting the result according to the Pauli algebra.

Variational method and optimization

Given a parametrized ansatz for the ground state eigenstate, with parameters that can be modified, one is sure to find the parametrized state that is closest to the ground state based on the variational method of quantum mechanics. Using classical algorithms in a digital computer, the parameters of the ansatz can be optimized. For this minimization, it is necessary to find the minima of a multivariable function. Classical optimizers using gradient descent can be used for this purpose.

Formulation

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Variational quantum eigensolver" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

For a given Hamiltonian (H) and a state vector if we can vary arbitrarily then will be the ground state energy and would be a ground state (assuming no degeneracy). But the above minimization problem over all possible states , where state is dimensional, is impractical. Thus to restrict the search space to a more practical size (eg. poly(n)), we need to restrict the to only a subset of possible n-qubit states which is based on conventional physics, chemistry and quantum mechanics knowledge.

Algorithm

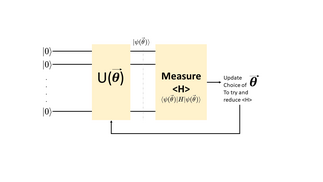

The adjoining figure illustrates the high level steps in the VQE algorithm.

The circuit controls the subset of possible states that can be created, and the parameter contains the variational parameters, where the number of parameters chosen are enough to lend the algorithm expressive power to compute the ground state of the system, but not too big to increase the computational cost of the optimization step.

By running the circuit many times and constantly updating the parameters to find the global minima of the expectation value of the desired observable, one can approach the ground state of the given system and store it in a quantum processor as a series of quantum gate instructions.

In case of gradient descent, its required to minimize a cost function where for the VQE case . The update rule is:

where r is the learning rate (step size) and

In order to compute the gradients, the parameter shift rule is used.

Example

Considering a single Pauli gate example:

where P = X,Y or Z, then

As, . Thus,

The above result has interesting properties as:

- The same circuit can be used to evaluate and

- needs to be evaluated 2 times to arrive at the gradient value

- As the angle precision is large, gate precision can be kept low

Advantages and disadvantages

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Variational quantum eigensolver" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- The VQE circuit does not require many gates compared with quantum phase estimation algorithm (QPE), it is more robust to errors and lends itself well to error mitigation strategies.

- It is a heuristic method and thus does not guarantee convergence to the ground state value. The method is highly influenced by the choice of ansatz circuit and the optimization methods.

- Number of measurements required to conclude the value of ground state is higher compared to the QPE and scales approximately with the number of terms in the Hamiltonian.

- VQE can run on NISQ hardware.

- VQE is highly versatile, as problems (apart from chemistry) can be expressed as Hamiltonians.

Use

In chemistry

As of 2022, the variational quantum eigensolver can only simulate small molecules like the helium hydride ion or the beryllium hydride molecule. Larger molecules can be simulated by taking into account symmetry considerations. In 2020, a 12-qubit simulation of a hydrogen chain (H12) was demonstrated using Google's Sycamore quantum processor.

See also

Notes

- Full authors: Alberto Peruzzo, Jarrod McClean, Peter Shadbolt, Man-Hong Yung, Xiao-Qi Zhou, Peter J. Love, Alan Aspuru-Guzik and Jeremy L. O’Brien. All equally contributing.

References

- ^ Peruzzo, Alberto; McClean, Jarrod; Shadbolt, Peter; Yung, Man-Hong; Zhou, Xiao-Qi; Love, Peter J.; Aspuru-Guzik, Alán; O’Brien, Jeremy L. (2014). "A variational eigenvalue solver on a photonic quantum processor". Nature Communications. 5 (1): 4213. arXiv:1304.3061. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4213P. doi:10.1038/ncomms5213. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4124861. PMID 25055053.

- Bharti, Kishor; Cervera-Lierta, Alba; Kyaw, Thi Ha; Haug, Tobias; Alperin-Lea, Sumner; Anand, Abhinav; Degroote, Matthias; Heimonen, Hermanni; Kottmann, Jakob S.; Menke, Tim; Mok, Wai-Keong; Sim, Sukin; Kwek, Leong-Chuan; Aspuru-Guzik, Alán (2022-02-15). "Noisy intermediate-scale quantum algorithms". Reviews of Modern Physics. 94 (1): 015004. arXiv:2101.08448. Bibcode:2022RvMP...94a5004B. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.94.015004. hdl:10356/161272.

- McClean, Jarrod R; Romero, Jonathan; Babbush, Ryan; Aspuru-Guzik, Alán (2016-02-04). "The theory of variational hybrid quantum-classical algorithms". New Journal of Physics. 18 (2): 023023. arXiv:1509.04279. Bibcode:2016NJPh...18b3023M. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/18/2/023023. ISSN 1367-2630. S2CID 92988541.

- Steudtner, M (2019). Methods to simulate fermions on quantum computers with hardware limitations (PhD Thesis). University of Leiden.

- ^ Tilly, Jules; Chen, Hongxiang; Cao, Shuxiang; Picozzi, Dario; Setia, Kanav; Li, Ying; Grant, Edward; Wossnig, Leonard; Rungger, Ivan; Booth, George H.; Tennyson, Jonathan (2022-06-12). "The Variational Quantum Eigensolver: A review of methods and best practices". Physics Reports. 986: 1–128. arXiv:2111.05176. Bibcode:2022PhR...986....1T. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2022.08.003. S2CID 243861087.

- Seeley, Jacob T.; Richard, Martin J.; Love, Peter J. (2012-12-12). "The Bravyi-Kitaev transformation for quantum computation of electronic structure". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 137 (22): 224109. arXiv:1208.5986. Bibcode:2012JChPh.137v4109S. doi:10.1063/1.4768229. ISSN 0021-9606. PMID 23248989. S2CID 30699239.

- ^ Moll, Nikolaj; Barkoutsos, Panagiotis; Bishop, Lev S; Chow, Jerry M; Cross, Andrew; Egger, Daniel J; Filipp, Stefan; Fuhrer, Andreas; Gambetta, Jay M; Ganzhorn, Marc; Kandala, Abhinav; Mezzacapo, Antonio; Müller, Peter; Riess, Walter; Salis, Gian (2018). "Quantum optimization using variational algorithms on near-term quantum devices". Quantum Science and Technology. 3 (3): 030503. arXiv:1710.01022. Bibcode:2018QS&T....3c0503M. doi:10.1088/2058-9565/aab822. ISSN 2058-9565. S2CID 56376912.

- Tilly, Jules; Chen, Hongxiang; Cao, Shuxiang; Picozzi, Dario; Setia, Kanav; Li, Ying; Grant, Edward; Wossnig, Leonard; Rungger, Ivan; Booth, George H.; Tennyson, Jonathan (2022-06-12). "The Variational Quantum Eigensolver: A review of methods and best practices". Physics Reports. 986: 1–128. arXiv:2111.05176. Bibcode:2022PhR...986....1T. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2022.08.003. S2CID 243861087.

- Wierichs, David; Izaac, Josh; Wang, Cody; Lin, Cedric Yen-Yu (2022-01-01). "General parameter-shift rules for quantum gradients". Quantum. 6: 677. arXiv:2107.12390. doi:10.22331/q-2022-03-30-677.

- Markovich, Liubov; Malikis, Savvas; Polla, Stefano; Tura, Jordi (2024-06-01). "Parameter shift rule with optimal phase selection". Physical Review A. 109 (6). APS: 062429. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.109.062429.

- Kandala, Abhinav; Mezzacapo, Antonio; Temme, Kristan; Takita, Maika; Brink, Markus; Chow, Jerry M.; Gambetta, Jay M. (2017). "Hardware-efficient variational quantum eigensolver for small molecules and quantum magnets". Nature. 549 (7671): 242–246. arXiv:1704.05018. Bibcode:2017Natur.549..242K. doi:10.1038/nature23879. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 28905916. S2CID 4390182.

- Arute, Frank; Arya, Kunal; Babbush, Ryan; et al. (2020). "Hartree-Fock on a superconducting qubit quantum computer". Science. 369 (6507): 1084–1089. arXiv:2004.04174. Bibcode:2020Sci...369.1084.. doi:10.1126/science.abb9811. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 32855334. S2CID 215548188.

| Quantum information science | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||||||||

| Theorems | |||||||||

| Quantum communication |

| ||||||||

| Quantum algorithms | |||||||||

| Quantum complexity theory | |||||||||

| Quantum processor benchmarks | |||||||||

| Quantum computing models | |||||||||

| Quantum error correction | |||||||||

| Physical implementations |

| ||||||||

| Quantum programming | |||||||||

is written in terms of Pauli operators and irrelevant states are discarded (finite-dimensional space), it would consist of a linear combination of Pauli strings

is written in terms of Pauli operators and irrelevant states are discarded (finite-dimensional space), it would consist of a linear combination of Pauli strings  consisting of tensor products of

consisting of tensor products of  ), such that

), such that

,

, are numerical coefficients. Based on the coefficients, the number of Pauli strings can be reduced in order to optimize the calculation.

are numerical coefficients. Based on the coefficients, the number of Pauli strings can be reduced in order to optimize the calculation.

with parameters

with parameters  , has an expectation value of the energy or cost function given by

, has an expectation value of the energy or cost function given by

, the first qubit is to be measured in the x-axis, while the last two are to be measured in the y-axis of the

, the first qubit is to be measured in the x-axis, while the last two are to be measured in the y-axis of the  if we can vary

if we can vary  will be the ground state energy and

will be the ground state energy and  would be a ground state (assuming no degeneracy). But the above minimization problem over all possible states

would be a ground state (assuming no degeneracy). But the above minimization problem over all possible states  dimensional, is impractical. Thus to restrict the search space to a more practical size (eg. poly(n)), we need to restrict the

dimensional, is impractical. Thus to restrict the search space to a more practical size (eg. poly(n)), we need to restrict the  controls the subset of possible states that can be created, and the parameter

controls the subset of possible states that can be created, and the parameter  contains the variational parameters,

contains the variational parameters,  where the number of parameters chosen are enough to lend the algorithm expressive power to compute the ground state of the system, but not too big to increase the computational cost of the optimization step.

where the number of parameters chosen are enough to lend the algorithm expressive power to compute the ground state of the system, but not too big to increase the computational cost of the optimization step.

where for the VQE case

where for the VQE case  . The update rule is:

. The update rule is:

. Thus,

. Thus,

and

and

needs to be evaluated 2 times to arrive at the gradient value

needs to be evaluated 2 times to arrive at the gradient value is large, gate precision can be kept low

is large, gate precision can be kept low