| Part of a series on | |||||||

| Continuum mechanics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fick's laws of diffusion | |||||||

Laws

|

|||||||

| Solid mechanics | |||||||

Fluid mechanics

|

|||||||

Rheology

|

|||||||

| Scientists | |||||||

In materials science and continuum mechanics, viscoelasticity is the property of materials that exhibit both viscous and elastic characteristics when undergoing deformation. Viscous materials, like water, resist both shear flow and strain linearly with time when a stress is applied. Elastic materials strain when stretched and immediately return to their original state once the stress is removed.

Viscoelastic materials have elements of both of these properties and, as such, exhibit time-dependent strain. Whereas elasticity is usually the result of bond stretching along crystallographic planes in an ordered solid, viscosity is the result of the diffusion of atoms or molecules inside an amorphous material.

Background

In the nineteenth century, physicists such as James Clerk Maxwell, Ludwig Boltzmann, and Lord Kelvin researched and experimented with creep and recovery of glasses, metals, and rubbers. Viscoelasticity was further examined in the late twentieth century when synthetic polymers were engineered and used in a variety of applications. Viscoelasticity calculations depend heavily on the viscosity variable, η. The inverse of η is also known as fluidity, φ. The value of either can be derived as a function of temperature or as a given value (i.e. for a dashpot).

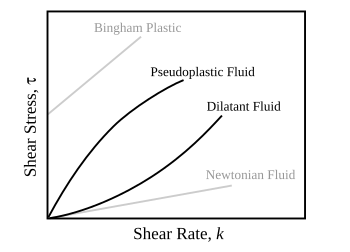

Depending on the change of strain rate versus stress inside a material, the viscosity can be categorized as having a linear, non-linear, or plastic response. When a material exhibits a linear response it is categorized as a Newtonian material. In this case the stress is linearly proportional to the strain rate. If the material exhibits a non-linear response to the strain rate, it is categorized as non-Newtonian fluid. There is also an interesting case where the viscosity decreases as the shear/strain rate remains constant. A material which exhibits this type of behavior is known as thixotropic. In addition, when the stress is independent of this strain rate, the material exhibits plastic deformation. Many viscoelastic materials exhibit rubber like behavior explained by the thermodynamic theory of polymer elasticity.

Some examples of viscoelastic materials are amorphous polymers, semicrystalline polymers, biopolymers, metals at very high temperatures, and bitumen materials. Cracking occurs when the strain is applied quickly and outside of the elastic limit. Ligaments and tendons are viscoelastic, so the extent of the potential damage to them depends on both the rate of the change of their length and the force applied.

A viscoelastic material has the following properties:

- hysteresis is seen in the stress–strain curve

- stress relaxation occurs: step constant strain causes decreasing stress

- creep occurs: step constant stress causes increasing strain

- its stiffness depends on the strain rate or the stress rate

Elastic versus viscoelastic behavior

Unlike purely elastic substances, a viscoelastic substance has an elastic component and a viscous component. The viscosity of a viscoelastic substance gives the substance a strain rate dependence on time. Purely elastic materials do not dissipate energy (heat) when a load is applied, then removed. However, a viscoelastic substance dissipates energy when a load is applied, then removed. Hysteresis is observed in the stress–strain curve, with the area of the loop being equal to the energy lost during the loading cycle. Since viscosity is the resistance to thermally activated plastic deformation, a viscous material will lose energy through a loading cycle. Plastic deformation results in lost energy, which is uncharacteristic of a purely elastic material's reaction to a loading cycle.

Specifically, viscoelasticity is a molecular rearrangement. When a stress is applied to a viscoelastic material such as a polymer, parts of the long polymer chain change positions. This movement or rearrangement is called creep. Polymers remain a solid material even when these parts of their chains are rearranging in order to accommodate the stress, and as this occurs, it creates a back stress in the material. When the back stress is the same magnitude as the applied stress, the material no longer creeps. When the original stress is taken away, the accumulated back stresses will cause the polymer to return to its original form. The material creeps, which gives the prefix visco-, and the material fully recovers, which gives the suffix -elasticity.

Linear viscoelasticity and nonlinear viscoelasticity

Linear viscoelasticity is when the function is separable in both creep response and load. All linear viscoelastic models can be represented by a Volterra equation connecting stress and strain: or where

- t is time

- is stress

- is strain

- and are instantaneous elastic moduli for creep and relaxation

- K(t) is the creep function

- F(t) is the relaxation function

Linear viscoelasticity is usually applicable only for small deformations.

Nonlinear viscoelasticity is when the function is not separable. It usually happens when the deformations are large or if the material changes its properties under deformations. Nonlinear viscoelasticity also elucidates observed phenomena such as normal stresses, shear thinning, and extensional thickening in viscoelastic fluids.

An anelastic material is a special case of a viscoelastic material: an anelastic material will fully recover to its original state on the removal of load.

When distinguishing between elastic, viscous, and forms of viscoelastic behavior, it is helpful to reference the time scale of the measurement relative to the relaxation times of the material being observed, known as the Deborah number (De) where: where

- is the relaxation time of the material

- is time

Dynamic modulus

Main article: Dynamic modulusViscoelasticity is studied using dynamic mechanical analysis, applying a small oscillatory stress and measuring the resulting strain.

- Purely elastic materials have stress and strain in phase, so that the response of one caused by the other is immediate.

- In purely viscous materials, strain lags stress by a 90 degree phase.

- Viscoelastic materials exhibit behavior somewhere in the middle of these two types of material, exhibiting some lag in strain.

A complex dynamic modulus G can be used to represent the relations between the oscillating stress and strain: where ; is the storage modulus and is the loss modulus: where and are the amplitudes of stress and strain respectively, and is the phase shift between them.

Constitutive models of linear viscoelasticity

Viscoelastic materials, such as amorphous polymers, semicrystalline polymers, biopolymers and even the living tissue and cells, can be modeled in order to determine their stress and strain or force and displacement interactions as well as their temporal dependencies. These models, which include the Maxwell model, the Kelvin–Voigt model, the standard linear solid model, and the Burgers model, are used to predict a material's response under different loading conditions.

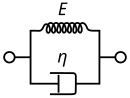

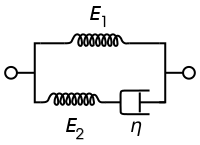

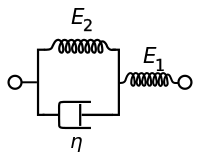

Viscoelastic behavior has elastic and viscous components modeled as linear combinations of springs and dashpots, respectively. Each model differs in the arrangement of these elements, and all of these viscoelastic models can be equivalently modeled as electrical circuits.

In an equivalent electrical circuit, stress is represented by current, and strain rate by voltage. The elastic modulus of a spring is analogous to the inverse of a circuit's inductance (it stores energy) and the viscosity of a dashpot to a circuit's resistance (it dissipates energy).

The elastic components, as previously mentioned, can be modeled as springs of elastic constant E, given the formula: where σ is the stress, E is the elastic modulus of the material, and ε is the strain that occurs under the given stress, similar to Hooke's law.

The viscous components can be modeled as dashpots such that the stress–strain rate relationship can be given as, where σ is the stress, η is the viscosity of the material, and dε/dt is the time derivative of strain.

The relationship between stress and strain can be simplified for specific stress or strain rates. For high stress or strain rates/short time periods, the time derivative components of the stress–strain relationship dominate. In these conditions it can be approximated as a rigid rod capable of sustaining high loads without deforming. Hence, the dashpot can be considered to be a "short-circuit".

Conversely, for low stress states/longer time periods, the time derivative components are negligible and the dashpot can be effectively removed from the system – an "open" circuit. As a result, only the spring connected in parallel to the dashpot will contribute to the total strain in the system.

Maxwell model

Main article: Maxwell material

The Maxwell model can be represented by a purely viscous damper and a purely elastic spring connected in series, as shown in the diagram. The model can be represented by the following equation:

Under this model, if the material is put under a constant strain, the stresses gradually relax. When a material is put under a constant stress, the strain has two components. First, an elastic component occurs instantaneously, corresponding to the spring, and relaxes immediately upon release of the stress. The second is a viscous component that grows with time as long as the stress is applied. The Maxwell model predicts that stress decays exponentially with time, which is accurate for most polymers. One limitation of this model is that it does not predict creep accurately. The Maxwell model for creep or constant-stress conditions postulates that strain will increase linearly with time. However, polymers for the most part show the strain rate to be decreasing with time.

This model can be applied to soft solids: thermoplastic polymers in the vicinity of their melting temperature, fresh concrete (neglecting its aging), and numerous metals at a temperature close to their melting point.

The equation introduced here, however, lacks a consistent derivation from more microscopic model and is not observer independent. The Upper-convected Maxwell model is its sound formulation in tems of the Cauchy stress tensor and constitutes the simplest tensorial constitutive model for viscoelasticity (see e.g. or ).

Kelvin–Voigt model

Main article: Kelvin–Voigt material

The Kelvin–Voigt model, also known as the Voigt model, consists of a Newtonian damper and Hookean elastic spring connected in parallel, as shown in the picture. It is used to explain the creep behaviour of polymers.

The constitutive relation is expressed as a linear first-order differential equation:

This model represents a solid undergoing reversible, viscoelastic strain. Upon application of a constant stress, the material deforms at a decreasing rate, asymptotically approaching the steady-state strain. When the stress is released, the material gradually relaxes to its undeformed state. At constant stress (creep), the model is quite realistic as it predicts strain to tend to σ/E as time continues to infinity. Similar to the Maxwell model, the Kelvin–Voigt model also has limitations. The model is extremely good with modelling creep in materials, but with regards to relaxation the model is much less accurate.

This model can be applied to organic polymers, rubber, and wood when the load is not too high.

Standard linear solid model

Main article: Standard linear solid modelThe standard linear solid model, also known as the Zener model, consists of two springs and a dashpot. It is the simplest model that describes both the creep and stress relaxation behaviors of a viscoelastic material properly. For this model, the governing constitutive relations are:

| Maxwell representation | Kelvin representation |

|---|---|

|

|

Under a constant stress, the modeled material will instantaneously deform to some strain, which is the instantaneous elastic portion of the strain. After that it will continue to deform and asymptotically approach a steady-state strain, which is the retarded elastic portion of the strain. Although the standard linear solid model is more accurate than the Maxwell and Kelvin–Voigt models in predicting material responses, mathematically it returns inaccurate results for strain under specific loading conditions.

Jeffreys model

The Jeffreys model like the Zener model is a three element model. It consist of two dashpots and a spring.

It was proposed in 1929 by Harold Jeffreys to study Earth's mantle.

Burgers model

Main article: Burgers materialThe Burgers model consists of either two Maxwell components in parallel or a Kelvin–Voigt component, a spring and a dashpot in series. For this model, the governing constitutive relations are:

| Maxwell representation | Kelvin representation |

|---|---|

|

|

This model incorporates viscous flow into the standard linear solid model, giving a linearly increasing asymptote for strain under fixed loading conditions.

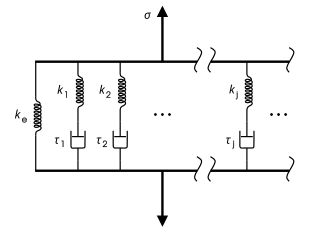

Generalized Maxwell model

Main article: Generalized Maxwell model

The generalized Maxwell model, also known as the Wiechert model, is the most general form of the linear model for viscoelasticity. It takes into account that the relaxation does not occur at a single time, but at a distribution of times. Due to molecular segments of different lengths with shorter ones contributing less than longer ones, there is a varying time distribution. The Wiechert model shows this by having as many spring–dashpot Maxwell elements as necessary to accurately represent the distribution. The figure on the right shows the generalised Wiechert model. Applications: metals and alloys at temperatures lower than one quarter of their absolute melting temperature (expressed in K).

Constitutive models for nonlinear viscoelasticity

Non-linear viscoelastic constitutive equations are needed to quantitatively account for phenomena in fluids like differences in normal stresses, shear thinning, and extensional thickening. Necessarily, the history experienced by the material is needed to account for time-dependent behavior, and is typically included in models as a history kernel K.

Second-order fluid

Main article: Second-order fluidThe second-order fluid is typically considered the simplest nonlinear viscoelastic model, and typically occurs in a narrow region of materials behavior occurring at high strain amplitudes and Deborah number between Newtonian fluids and other more complicated nonlinear viscoelastic fluids. The second-order fluid constitutive equation is given by:

where:

- is the identity tensor

- is the deformation tensor

- denote viscosity, and first and second normal stress coefficients, respectively

- denotes the upper-convected derivative of the deformation tensor where and is the material time derivative of the deformation tensor.

Upper-convected Maxwell model

Main article: Upper-convected Maxwell modelThe upper-convected Maxwell model incorporates nonlinear time behavior into the viscoelastic Maxwell model, given by:

where denotes the stress tensor.

Oldroyd-B model

Main article: Oldroyd-B modelThe Oldroyd-B model is an extension of the Upper Convected Maxwell model and is interpreted as a solvent filled with elastic bead and spring dumbbells. The model is named after its creator James G. Oldroyd.

The model can be written as: where:

- is the stress tensor;

- is the relaxation time;

- is the retardation time = ;

- is the upper convected time derivative of stress tensor:

- is the fluid velocity;

- is the total viscosity composed of solvent and polymer components, ;

- is the deformation rate tensor or rate of strain tensor, .

Whilst the model gives good approximations of viscoelastic fluids in shear flow, it has an unphysical singularity in extensional flow, where the dumbbells are infinitely stretched. This is, however, specific to idealised flow; in the case of a cross-slot geometry the extensional flow is not ideal, so the stress, although singular, remains integrable, although the stress is infinite in a correspondingly infinitely small region.

If the solvent viscosity is zero, the Oldroyd-B becomes the upper convected Maxwell model.

Wagner model

Main article: Wagner modelWagner model is might be considered as a simplified practical form of the Bernstein–Kearsley–Zapas model. The model was developed by German rheologist Manfred Wagner.

For the isothermal conditions the model can be written as:

where:

- is the Cauchy stress tensor as function of time t,

- p is the pressure

- is the unity tensor

- M is the memory function showing, usually expressed as a sum of exponential terms for each mode of relaxation: where for each mode of the relaxation, is the relaxation modulus and is the relaxation time;

- is the strain damping function that depends upon the first and second invariants of Finger tensor .

The strain damping function is usually written as: If the value of the strain hardening function is equal to one, then the deformation is small; if it approaches zero, then the deformations are large.

Prony series

Main article: Prony's methodIn a one-dimensional relaxation test, the material is subjected to a sudden strain that is kept constant over the duration of the test, and the stress is measured over time. The initial stress is due to the elastic response of the material. Then, the stress relaxes over time due to the viscous effects in the material. Typically, either a tensile, compressive, bulk compression, or shear strain is applied. The resulting stress vs. time data can be fitted with a number of equations, called models. Only the notation changes depending on the type of strain applied: tensile-compressive relaxation is denoted , shear is denoted , bulk is denoted . The Prony series for the shear relaxation is

where is the long term modulus once the material is totally relaxed, are the relaxation times (not to be confused with in the diagram); the higher their values, the longer it takes for the stress to relax. The data is fitted with the equation by using a minimization algorithm that adjust the parameters () to minimize the error between the predicted and data values.

An alternative form is obtained noting that the elastic modulus is related to the long term modulus by

Therefore,

This form is convenient when the elastic shear modulus is obtained from data independent from the relaxation data, and/or for computer implementation, when it is desired to specify the elastic properties separately from the viscous properties, as in Simulia (2010).

A creep experiment is usually easier to perform than a relaxation one, so most data is available as (creep) compliance vs. time. Unfortunately, there is no known closed form for the (creep) compliance in terms of the coefficient of the Prony series. So, if one has creep data, it is not easy to get the coefficients of the (relaxation) Prony series, which are needed for example in. An expedient way to obtain these coefficients is the following. First, fit the creep data with a model that has closed form solutions in both compliance and relaxation; for example the Maxwell-Kelvin model (eq. 7.18-7.19) in Barbero (2007) or the Standard Solid Model (eq. 7.20-7.21) in Barbero (2007) (section 7.1.3). Once the parameters of the creep model are known, produce relaxation pseudo-data with the conjugate relaxation model for the same times of the original data. Finally, fit the pseudo data with the Prony series.

Effect of temperature

Main article: Time–temperature superpositionThe secondary bonds of a polymer constantly break and reform due to thermal motion. Application of a stress favors some conformations over others, so the molecules of the polymer will gradually "flow" into the favored conformations over time. Because thermal motion is one factor contributing to the deformation of polymers, viscoelastic properties change with increasing or decreasing temperature. In most cases, the creep modulus, defined as the ratio of applied stress to the time-dependent strain, decreases with increasing temperature. Generally speaking, an increase in temperature correlates to a logarithmic decrease in the time required to impart equal strain under a constant stress. In other words, it takes less work to stretch a viscoelastic material an equal distance at a higher temperature than it does at a lower temperature.

More detailed effect of temperature on the viscoelastic behavior of polymer can be plotted as shown.

There are mainly five regions (some denoted four, which combines IV and V together) included in the typical polymers.

- Region I: Glassy state of the polymer is presented in this region. The temperature in this region for a given polymer is too low to endow molecular motion. Hence the motion of the molecules is frozen in this area. The mechanical property is hard and brittle in this region.

- Region II: Polymer passes glass transition temperature in this region. Beyond Tg, the thermal energy provided by the environment is enough to unfreeze the motion of molecules. The molecules are allowed to have local motion in this region hence leading to a sharp drop in stiffness compared to Region I.

- Region III: Rubbery plateau region. Materials lie in this region would exist long-range elasticity driven by entropy. For instance, a rubber band is disordered in the initial state of this region. When stretching the rubber band, you also align the structure to be more ordered. Therefore, when releasing the rubber band, it will spontaneously seek higher entropy state hence goes back to its initial state. This is what we called entropy-driven elasticity shape recovery.

- Region IV: The behavior in the rubbery flow region is highly time-dependent. Polymers in this region would need to use a time-temperature superposition to get more detailed information to cautiously decide how to use the materials. For instance, if the material is used to cope with short interaction time purpose, it could present as 'hard' material. While using for long interaction time purposes, it would act as 'soft' material.

- Region V: Viscous polymer flows easily in this region. Another significant drop in stiffness.

Extreme cold temperatures can cause viscoelastic materials to change to the glass phase and become brittle. For example, exposure of pressure sensitive adhesives to extreme cold (dry ice, freeze spray, etc.) causes them to lose their tack, resulting in debonding.

Viscoelastic creep

Main article: Creep (deformation)

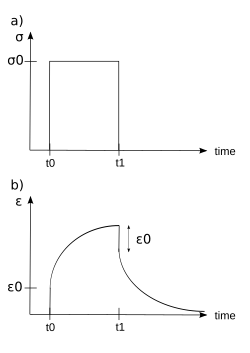

When subjected to a step constant stress, viscoelastic materials experience a time-dependent increase in strain. This phenomenon is known as viscoelastic creep.

At time , a viscoelastic material is loaded with a constant stress that is maintained for a sufficiently long time period. The material responds to the stress with a strain that increases until the material ultimately fails, if it is a viscoelastic liquid. If, on the other hand, it is a viscoelastic solid, it may or may not fail depending on the applied stress versus the material's ultimate resistance. When the stress is maintained for a shorter time period, the material undergoes an initial strain until a time , after which the strain immediately decreases (discontinuity) then gradually decreases at times to a residual strain.

Viscoelastic creep data can be presented by plotting the creep modulus (constant applied stress divided by total strain at a particular time) as a function of time. Below its critical stress, the viscoelastic creep modulus is independent of stress applied. A family of curves describing strain versus time response to various applied stress may be represented by a single viscoelastic creep modulus versus time curve if the applied stresses are below the material's critical stress value.

Viscoelastic creep is important when considering long-term structural design. Given loading and temperature conditions, designers can choose materials that best suit component lifetimes.

Measurement

Shear rheometry

Shear rheometers are based on the idea of putting the material to be measured between two plates, one or both of which move in a shear direction to induce stresses and strains in the material. The testing can be done at constant strain rate, stress, or in an oscillatory fashion (a form of dynamic mechanical analysis). Shear rheometers are typically limited by edge effects where the material may leak out from between the two plates and slipping at the material/plate interface.

Extensional rheometry

Extensional rheometers, also known as extensiometers, measure viscoelastic properties by pulling a viscoelastic fluid, typically uniaxially. Because this typically makes use of capillary forces and confines the fluid to a narrow geometry, the technique is often limited to fluids with relatively low viscosity like dilute polymer solutions or some molten polymers. Extensional rheometers are also limited by edge effects at the ends of the extensiometer and pressure differences between inside and outside the capillary.

Despite the apparent limitations mentioned above, extensional rheometry can also be performed on high viscosity fluids. Although this requires the use of different instruments, these techniques and apparatuses allow for the study of the extensional viscoelastic properties of materials such as polymer melts. Three of the most common extensional rheometry instruments developed within the last 50 years are the Meissner-type rheometer, the filament stretching rheometer (FiSER), and the Sentmanat Extensional Rheometer (SER).

The Meissner-type rheometer, developed by Meissner and Hostettler in 1996, uses two sets of counter-rotating rollers to strain a sample uniaxially. This method uses a constant sample length throughout the experiment, and supports the sample in between the rollers via an air cushion to eliminate sample sagging effects. It does suffer from a few issues – for one, the fluid may slip at the belts which leads to lower strain rates than one would expect. Additionally, this equipment is challenging to operate and costly to purchase and maintain.

The FiSER rheometer simply contains fluid in between two plates. During an experiment, the top plate is held steady and a force is applied to the bottom plate, moving it away from the top one. The strain rate is measured by the rate of change of the sample radius at its middle. It is calculated using the following equation: where is the mid-radius value and is the strain rate. The viscosity of the sample is then calculated using the following equation: where is the sample viscosity, and is the force applied to the sample to pull it apart.

Much like the Meissner-type rheometer, the SER rheometer uses a set of two rollers to strain a sample at a given rate. It then calculates the sample viscosity using the well known equation: where is the stress, is the viscosity and is the strain rate. The stress in this case is determined via torque transducers present in the instrument. The small size of this instrument makes it easy to use and eliminates sample sagging between the rollers. A schematic detailing the operation of the SER extensional rheometer can be found on the right.

Other methods

Though there are many instruments that test the mechanical and viscoelastic response of materials, broadband viscoelastic spectroscopy (BVS) and resonant ultrasound spectroscopy (RUS) are more commonly used to test viscoelastic behavior because they can be used above and below ambient temperatures and are more specific to testing viscoelasticity. These two instruments employ a damping mechanism at various frequencies and time ranges with no appeal to time–temperature superposition. Using BVS and RUS to study the mechanical properties of materials is important to understanding how a material exhibiting viscoelasticity will perform.

See also

- Bingham plastic

- Biomaterial

- Biomechanics

- Blood viscoelasticity

- Constant viscosity elastic fluids

- Deformation index

- Glass transition

- Pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Rheology

- Rubber elasticity

- Silly Putty

- Viscoelasticity of bone

- Viscoplasticity

- Visco-elastic jets

References

- ^ Meyers and Chawla (1999): "Mechanical Behavior of Materials", 98-103.

- ^ McCrum, Buckley, and Bucknell (2003): "Principles of Polymer Engineering," 117-176.

- ^ Macosko, Christopher W. (1994). Rheology : principles, measurements, and applications. New York: VCH. ISBN 978-1-60119-575-3. OCLC 232602530.

- Biswas, Abhijit; Manivannan, M.; Srinivasan, Mandyam A. (2015). "Multiscale Layered Biomechanical Model of the Pacinian Corpuscle". IEEE Transactions on Haptics. 8 (1): 31–42. doi:10.1109/TOH.2014.2369416. PMID 25398182. S2CID 24658742.

- ^ Van Vliet, Krystyn J. (2006). "3.032 Mechanical Behavior of Materials"

- ^ Cacopardo, Ludovica (Jan 2019). "Engineering hydrogel viscoelasticity". Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 89: 162–167. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.09.031. hdl:11568/930491. PMID 30286375. S2CID 52918639 – via Elsevier. Cite error: The named reference ":0" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Larson, Ronald G. (28 January 1999). The Structure and Rheology of Complex Fluids (Topics in Chemical Engineering): Larson, Ronald G.: 9780195121971: Amazon.com: Books. Oup USA. ISBN 019512197X.

- Tanner, Roger I. (1988). Engineering Rheologu. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-19-856197-0.

- Barnes, Howard A.; Hutton, John Fletcher; Walters, K. (1989). An Introduction to Rheology. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-87140-4.

- Bird, R. Byron (1987-05-27). Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids, Volume 1: Fluid Mechanics. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-80245-7.

- Roylance, David (2001); "Engineering Viscoelasticity", 14–15

- Drapaca, C.S.; Sivaloganathan, S.; Tenti, G. (2007-10-01). "Nonlinear Constitutive Laws in Viscoelasticity". Mathematics and Mechanics of Solids. 12 (5): 475–501. doi:10.1177/1081286506062450. ISSN 1081-2865. S2CID 121260529.

- Oldroyd, James (February 1950). "On the Formulation of Rheological Equations of State". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 200 (1063): 523–541. Bibcode:1950RSPSA.200..523O. doi:10.1098/rspa.1950.0035. S2CID 123239889.

- Owens, R. G.; Phillips, T. N. (2002). Computational Rheology. Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-86094-186-3.

- ^ Poole, Rob (October 2007). "Purely elastic flow asymmetries". Physical Review Letters. 99 (16): 164503. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..99p4503P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.164503. hdl:10400.6/634. PMID 17995258.

- Wagner, Manfred (1976). "Analysis of time-dependent non-linear stress-growth data for shear and elongational flow of a low-density branched polyethylene melt". Rheologica Acta. 15 (2): 136–142. Bibcode:1976AcRhe..15..136W. doi:10.1007/BF01517505. S2CID 96165087.

- Wagner, Manfred (1977). "Prediction of primary normal stress difference from shear viscosity data usinga single integral constitutive equation". Rheologica Acta. 16 (1977): 43–50. Bibcode:1977AcRhe..16...43W. doi:10.1007/BF01516928. S2CID 98599256.

- E. J. Barbero. "Time-temperature-age Superposition Principle for Predicting Long-term Response of Linear Viscoelastic Materials", chapter 2 in Creep and fatigue in polymer matrix composites. Woodhead, 2011.

- ^ Simulia. Abaqus Analysis User's Manual, 19.7.1 "Time domain vicoelasticity", 6.10 edition, 2010

- Computer Aided Material Preselection by Uniform Standards

- ^ E. J. Barbero. Finite Element Analysis of Composite Materials. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 2007.

- S.A. Baeurle, A. Hotta, A.A. Gusev, Polymer 47, 6243-6253 (2006).

- Aklonis., J.J. (1981). "Mechanical properties of polymer". J Chem Educ. 58 (11): 892. Bibcode:1981JChEd..58..892A. doi:10.1021/ed058p892.

- I. M., Kalogeras (2012). "The nature of the glassy state: structure and glass transitions". Journal of Materials Education. 34 (3): 69.

- I, Emri (2010). Time-dependent behavior of solid polymers.

- Rosato, et al. (2001): "Plastics Design Handbook", 63-64.

- Magnin, A.; Piau, J.M. (1987-01-01). "Shear rheometry of fluids with a yield stress". Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics. 23: 91–106. Bibcode:1987JNNFM..23...91M. doi:10.1016/0377-0257(87)80012-5. ISSN 0377-0257.

- ^ Dealy, J.M. (1978-01-01). "Extensional Rheometers for molten polymers; a review". Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics. 4 (1–2): 9–21. Bibcode:1978JNNFM...4....9D. doi:10.1016/0377-0257(78)85003-4. ISSN 0377-0257.

- Meissner, J.; Hostettler, J. (1994-01-01). "A new elongational rheometer for polymer melts and other highly viscoelastic liquids". Rheologica Acta. 33 (1): 1–21. Bibcode:1994AcRhe..33....1M. doi:10.1007/BF00453459. ISSN 1435-1528. S2CID 93395453.

- Bach, Anders; Rasmussen, Henrik Koblitz; Hassager, Ole (March 2003). "Extensional viscosity for polymer melts measured in the filament stretching rheometer". Journal of Rheology. 47 (2): 429–441. Bibcode:2003JRheo..47..429B. doi:10.1122/1.1545072. ISSN 0148-6055. S2CID 44889615.

- Sentmanat, Martin L. (2004-12-01). "Miniature universal testing platform: from extensional melt rheology to solid-state deformation behavior". Rheologica Acta. 43 (6): 657–669. Bibcode:2004AcRhe..43..657S. doi:10.1007/s00397-004-0405-4. ISSN 1435-1528. S2CID 73671672.

- Rod Lakes (1998). Viscoelastic solids. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-9658-1.

- Silbey and Alberty (2001): Physical Chemistry, 857. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Alan S. Wineman and K. R. Rajagopal (2000): Mechanical Response of Polymers: An Introduction

- Allen and Thomas (1999): The Structure of Materials, 51.

- Crandal et al. (1999): An Introduction to the Mechanics of Solids 348

- J. Lemaitre and J. L. Chaboche (1994) Mechanics of solid materials

- Yu. Dimitrienko (2011) Nonlinear continuum mechanics and Large Inelastic Deformations, Springer, 772p

| Non-Newtonian fluids | |

|---|---|

| Effects | |

| Properties |

|

| Generalized Newtonian fluids | |

) to a change in strain rate (

) to a change in strain rate ( )

)

, where

, where  is strain.

is strain. or

or

where

where

is

is  is

is  and

and  are instantaneous

are instantaneous  where

where

is the relaxation time of the material

is the relaxation time of the material is time

is time where

where  ;

;  is the storage modulus and

is the storage modulus and  is the loss modulus:

is the loss modulus:

where

where  and

and  are the amplitudes of stress and strain respectively, and

are the amplitudes of stress and strain respectively, and  is the phase shift between them.

is the phase shift between them.

where σ is the stress, E is the elastic modulus of the material, and ε is the strain that occurs under the given stress, similar to

where σ is the stress, E is the elastic modulus of the material, and ε is the strain that occurs under the given stress, similar to  where σ is the stress, η is the viscosity of the material, and dε/dt is the time derivative of strain.

where σ is the stress, η is the viscosity of the material, and dε/dt is the time derivative of strain.

is the identity tensor

is the identity tensor is the deformation tensor

is the deformation tensor denote viscosity, and first and second normal stress coefficients, respectively

denote viscosity, and first and second normal stress coefficients, respectively denotes the upper-convected derivative of the deformation tensor where

denotes the upper-convected derivative of the deformation tensor where  and

and  is the material time derivative of the deformation tensor.

is the material time derivative of the deformation tensor. where

where  denotes the stress tensor.

denotes the stress tensor.

where:

where:

is the

is the  is the relaxation time;

is the relaxation time; is the retardation time =

is the retardation time =  ;

; is the

is the

is the fluid velocity;

is the fluid velocity; is the total

is the total  ;

; .

.

is the

is the  where for each mode of the relaxation,

where for each mode of the relaxation,  is the relaxation modulus and

is the relaxation modulus and  is the relaxation time;

is the relaxation time; is the strain damping function that depends upon the first and second

is the strain damping function that depends upon the first and second  .

. If the value of the strain hardening function is equal to one, then the deformation is small; if it approaches zero, then the deformations are large.

If the value of the strain hardening function is equal to one, then the deformation is small; if it approaches zero, then the deformations are large.

, shear is denoted

, shear is denoted  , bulk is denoted

, bulk is denoted  . The Prony series for the shear relaxation is

. The Prony series for the shear relaxation is

is the long term modulus once the material is totally relaxed,

is the long term modulus once the material is totally relaxed,  are the relaxation times (not to be confused with

are the relaxation times (not to be confused with  ) to minimize the error between the predicted and data values.

) to minimize the error between the predicted and data values.

is obtained from data independent from the relaxation data, and/or for computer implementation, when it is desired to specify the elastic properties separately from the viscous properties, as in Simulia (2010).

is obtained from data independent from the relaxation data, and/or for computer implementation, when it is desired to specify the elastic properties separately from the viscous properties, as in Simulia (2010).

, a viscoelastic material is loaded with a constant stress that is maintained for a sufficiently long time period. The material responds to the stress with a strain that increases until the material ultimately fails, if it is a viscoelastic liquid. If, on the other hand, it is a viscoelastic solid, it may or may not fail depending on the applied stress versus the material's ultimate resistance. When the stress is maintained for a shorter time period, the material undergoes an initial strain until a time

, a viscoelastic material is loaded with a constant stress that is maintained for a sufficiently long time period. The material responds to the stress with a strain that increases until the material ultimately fails, if it is a viscoelastic liquid. If, on the other hand, it is a viscoelastic solid, it may or may not fail depending on the applied stress versus the material's ultimate resistance. When the stress is maintained for a shorter time period, the material undergoes an initial strain until a time  , after which the strain immediately decreases (discontinuity) then gradually decreases at times

, after which the strain immediately decreases (discontinuity) then gradually decreases at times  to a residual strain.

to a residual strain.

where

where  is the mid-radius value and

is the mid-radius value and  is the strain rate. The viscosity of the sample is then calculated using the following equation:

is the strain rate. The viscosity of the sample is then calculated using the following equation:

where

where  is the sample viscosity, and

is the sample viscosity, and  is the force applied to the sample to pull it apart.

is the force applied to the sample to pull it apart.

where

where