Flush toilets with cisterns

Flush toilets with cisternsTop: A sit toilet

Bottom: A squat toilet

A flush toilet (also known as a flushing toilet, water closet (WC); see also toilet names) is a toilet that disposes of human waste (i.e., urine and feces) by collecting it in a bowl and then using the force of water to channel it ("flush" it) through a drainpipe to another location for treatment, either nearby or at a communal facility. Flush toilets can be designed for sitting or squatting (often regionally differentiated). Most modern sewage treatment systems are also designed to process specially designed toilet paper, and there is increasing interest for flushable wet wipes. Porcelain (sometimes with vitreous china) is a popular material for these toilets, although public or institutional ones may be metal, etc.

Flush toilets are a type of plumbing fixture, and usually incorporate a bend called a trap (S-, U-, J-, or P-shaped) that causes water to collect in the toilet bowl – to hold the waste and act as a seal against noxious sewer gases. Urban and suburban flush toilets are connected to a sewerage system that conveys wastewater to a sewage treatment plant; rurally, a septic tank or composting system is mostly used.

The opposite of a flush toilet is a dry toilet, which uses no water for flushing. Associated devices are urinals, which primarily dispose of urine, and bidets, which use water to cleanse the anus, perineum, and vulva after using the toilet.

Operation

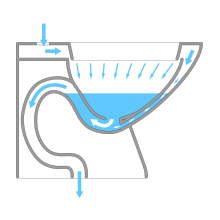

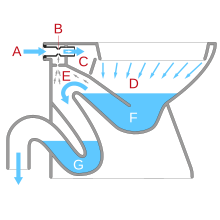

A typical flush toilet is a fixed, vitreous ceramic bowl (also known as a pan) which is connected to a drain. After use, the bowl is emptied and cleaned by the rapid flow of water into the bowl. This flush may flow from a dedicated tank (cistern), a high-pressure water pipe controlled by a flush valve, or by manually pouring water into the bowl. Tanks and valves are normally operated by the user, by pressing a button, pushing down on a handle, pulling a lever or pulling a chain. The water is directed around the bowl by a molded flushing rim around the top of the bowl or by one or more jets, so that the entire internal surface of the bowl is rinsed with water.

Mechanical flush from a cistern

A typical toilet has a tank fixed above the bowl which contains a fixed volume of water, and two devices. The first device allows part of the contents of the tank (usually in the 3–6 L or 3⁄4–1+1⁄2 US gallons range) to be discharged rapidly into the toilet bowl, causing the contents of the bowl to be swept or sucked out of the toilet and into the drain, when the user operates the flush. The second device automatically allows water to enter the tank until the water level is appropriate for a flush.

The water may be discharged through a "toilet flapper valve" (not to be confused with a type of check valve), or through a siphon. A float usually controls the refilling device.

Mechanical flush from a high-pressure water supply

Toilets without cisterns are often flushed through a simple flush valve or "Flushometer" connected directly to the water supply. These are designed to rapidly discharge a limited volume of water when the lever or button is pressed then released.

Manual flush (pour flush)

A toilet does not need be connected to a water supply, but may be pour-flushed. This type of flush toilet has no cistern or permanent water supply, but is flushed by pouring in a few litres of water from a container. The flushing can use as little as 2–3 L (1⁄2–3⁄4 US gallon). This type of toilet is common in many Asian countries. The toilet can be connected to one or two pits, in which case it is called a "pour flush pit latrine" or a "twin pit pour flush pit latrine". It can also be connected to a septic tank.

Vacuum toilet

A vacuum toilet is a flush toilet that is connected to a vacuum sewer system, and removes waste by suction. They may use very little water (less than one-quarter litre or 1⁄16 US gallon per flush) or none. Some flush with coloured disinfectant solution rather than with water. They may be used to separate blackwater and greywater, and process them separately (for instance, the fairly dry blackwater can be used for biogas production, or in a composting toilet).

Passenger train toilets, aircraft lavatories, bus toilets, and ships with plumbing often use vacuum toilets. The lower water usage saves weight and avoids water slopping out of the toilet bowl in motion. Aboard vehicles, a portable collection chamber is used; if it is filled by positive pressure from an intermediate vacuum chamber, it need not be kept under vacuum.

Flushing systems

The flushing system provides a large flow of water into the bowl. They normally take the form of either fixed tanks of water or flush valves.

Flush tanks

Flush tanks or cisterns usually incorporate a mechanism to release water from the tank and an automatic valve to allow the cistern to be refilled automatically.

This system is suitable for locations plumbed with 12.7 or 9.5 mm (1⁄2 or 3⁄8 inch) water pipes which cannot supply water quickly enough to flush the toilet; the tank is needed to supply a large volume of water in a short time. The tank typically collects between 6 and 17 L (1.6 and 4.5 US gallons) of water over a period of time. In modern installations the storage tank is usually mounted directly above and behind the bowl.

Older installations, known as "high suite combinations", used a high-level cistern (tank), fitted above head height, activated by a pull chain connected to a flush lever on the cistern. When more modern close-coupled cistern and bowl combinations were first introduced, these were first referred to as "low suite combinations". Modern versions have a neater-looking low-level cistern with a lever that the user can reach directly, or a close-coupled cistern that is even lower down and fixed directly to the bowl. In recent decades the close coupled tank–bowl combination has become the most popular residential system, as it has been found by ceramic engineers that improved waterway design is a more effective way to enhance the bowl's flushing action than high tank mounting.

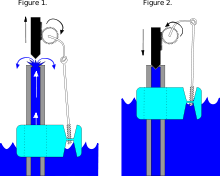

Tank fill valve

Tank fill valves are found in all tank-style toilets. The valves are of two main designs: the side-float design and the concentric-float design. The side-float design has existed for over a hundred years. The concentric design has only existed since 1957 but is gradually becoming more popular than the side-float design.

The side-float design uses a float on the end of a lever to control the fill valve. The float is usually shaped like a ball, so the mechanism is often called a ball-valve or a ballcock (cock in this context is an alternative term for valve; see, for example, stopcock). Historically floats were made from copper sheet, but are now usually plastic. The float is located to one side of the main valve tower or inlet at the end of a rod or arm. As the float rises, so does the float-arm. The arm connects to the fill valve that shuts off the inflow of water when the float reaches a level at which the volume of water in the tank is sufficient to provide another flush.

The newer concentric-float fill valve consists of a tower which is encircled by a plastic float assembly. Operation is otherwise the same as a side-float fill valve, even though the float position is somewhat different. By virtue of its more compact layout, interference between the float and other obstacles (tank insulation, flush valve, and so on) is greatly reduced, thus increasing reliability. The concentric-float fill valve is also designed to signal to users automatically when there is a leak in the tank, by making much more noise when a leak is present than the older style side-float fill valve, which tends to be nearly silent when a slow leak is present.

Newer fill valves have a delayed action that will not start filling the tank/cistern until the flapper/drop valve has closed which saves some water.

Flapper-flush valve or drop valve

In tanks using a flapper-flush valve, the outlet at the bottom of the tank is covered by a buoyant (plastic or rubber) cover, or flapper, which is held in place against a fitting (the flush valve seat) by water pressure. The user pushes a lever to flush the toilet, which lifts the flush valve from the valve seat. The valve then floats clear of the seat, allowing the tank to empty quickly into the bowl. As the water level drops, the floating flush valve descends back to the bottom of the tank and covers the outlet pipe again. This system is common in homes in North America and in continental Europe. From 2001, due to a change in regulations, this flush system has also become available in the UK, where prior to that the siphon-type flush was mandated.

Dual flush versions of this design with push buttons are widely available. They have one level of water for liquid waste and a higher level for solid waste.

In North America, newer toilets have a 3 in (76 mm) flapper-flush valve. Older toilets have a 2 in (51 mm) flapper-flush valve. The larger flapper-flush valve is used on toilets that use less water, such as 1.6 US gal (6.1 L) per flush. Some have a bell inlet for a faster more effective flush.

A problem with the valve type flush mechanism is that it invariably starts to leak after a couple of years use due to wear and tear of the valve, particles, etc. trapped in the valve. Quite often this leakage is barely noticeable but adds up to a considerable water wastage. In the UK it has been found that between 5 and 8% of toilets (mostly dual flush drop valves) are leaking, each one between 215 and 400 L (57 and 106 US gallons) on average per day. Whilst they save more water than they leak, regular maintenance or use of a non-leaking flush mechanism will maximise water savings.

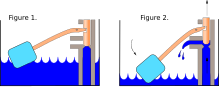

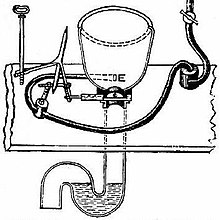

Siphon-flush mechanism

This system, invented by Albert Giblin and common in the UK, uses a storage tank similar to that used in the flapper-flush-valve system above. This flush valve system is sometimes referred to as a valveless system, since no valve as such is required.

The siphon is formed of a vertical pipe that links the flush pipe to a domed chamber inside the cistern. A perforated disc, covered by a flexible plate or flap, is fitted inside this chamber and is joined by a rod to the flush lever.

Pressing the lever raises the disc, forces water over the top of the siphon into the vertical pipe, and starts the siphonic flow. Water flows through the perforated disc past the flap until the cistern is empty, at which point air enters the siphon and the flush stops.

The advantage of a siphon over the flush valve is that it has no sealing washers that can wear out and cause leaks, whereas other valve types - flapper, drop valve do leak, invariably after a couple of years of use and they have reduced water savings due to the valves not being maintained in practice. The siphon membrane will require occasional replacement.

Until 1 January 2001, the use of siphon-type cisterns was mandatory in the UK but after that date the regulations additionally allowed pressure flushing cisterns and pressure flushing valves (though the latter remained forbidden in houses). Siphons can sometimes be more difficult to operate than a "flapper"-based flush valve because moving the lever requires more torque than a flapper system. This additional torque is required because a certain amount of water must be lifted up into the siphon passageway in order to initiate the siphon action in the tank. Splitting or jamming of the flexible flap covering the perforated disc can cause the cistern to stop working.

Dual-flush versions of the siphon cistern provide a shorter flush option by allowing air into the siphon to stop the siphon action before the tank is empty.

The siphon system can also be combined with an air box to allow multiple siphons to be installed in a single trough cistern.

High-pressure or pressure-assisted tanks

Pressure-assisted toilets are sometimes found in both private (single, multiple, and lodging) installations as well as light commercial installations (such as offices). Products from several companies use 5.5 to 4 L (1.4 to 1.0 US gallon) per flush.

The mechanism consists of a plastic tank hidden inside the typical ceramic cistern or an exposed metal tank/cistern. When the tank fills with water, the air trapped inside compresses. When the air pressure inside the plastic tank reaches a certain level, the tank stops filling with water. A high-pressure valve located in the center of the vessel holds the air and water inside until the user flushes the toilet.

During flushing, the user activates the valve via a button or lever, which releases the pressurized water into the bowl at a flow rate much higher than a conventional gravity-flow toilet. One advantage to this is lower water consumption than a gravity-flow toilet, or more effectiveness with a similar amount of water. As a result, the toilet does not clog as easily as those using non-pressurized mechanisms.

However, there are some financial and safety disadvantages. These toilets are generally more expensive to purchase, and the plastic tanks need to be replaced about every 10 years. They also have a noisier flush than other models. In addition, pressure-assisted tanks have been known to explode, causing serious injuries and property damage, resulting in a massive recall beginning in 2012 of over 1.4 million toilets equipped with the tank.

Some newer toilets use similar pressure-assist technology, along with a bowl and trapway designed to enhance the siphon effect; they use only 3.0 L (0.8 US gallons) per flush, or 1.9 L (0.5 US gallons) / 3.6 L (0.95 US gallons) for dual flush models. This design is also much quieter than other pressure-assist or flushometer toilets.

Tipping bucket type valve

A number of tipping bucket type cisterns have been developed. In the cistern is placed a tipping bucket with its axis aligned or perpendicular with the cistern. They have a lever which is rotated emptying the bucket which allows a variable flush. Usually the quantity of water is marked on the cistern and depending on the performance of the bowl a dual flush can be achieved e.g. 3⁄6 L (0.13 US gal), 3⁄4.5 L (0.18 US gal), 3⁄3 L (0.26 US gal), 1⁄2 L (0.13 US gal), etc. A normal or delayed action refill valve is used.

Tankless style with high-pressure (flushometer) valve

Main article: FlushometerIn 1906, William Sloan first made available his "flushometer" style toilet flush valve, incorporating his patented design. The design proved to be very popular and efficient and remains so to this day. Flushometer toilet flush valves are still often installed in commercial restrooms, and are frequently used for both toilets and urinals. Since they have no tank, they have no fill delay and can be used again immediately. They can be easily identified by their distinctive chrome pipe-work, and by the absence of a toilet tank or cistern, wherever they are employed.

Some flushometer models require the user to either depress a lever or press a button, which in turn opens a flush valve allowing mains-pressure water to flow directly into the toilet bowl or urinal. Other flushometer models are electronically triggered, using an infrared sensor to initiate the flushing process. Typically, on electronically triggered models, an override button is provided in case the user wishes to manually trigger flushing earlier. Some electronically triggered models also incorporate a true mechanical manual override which can be used in the event of the failure of the electronic system. In retrofit installations, a self-contained battery-powered or hard-wired unit can be added to an existing manual flushometer to flush automatically when a user departs.

Once a flushometer valve has been flushed, and after a preset interval, the flushometer mechanism closes the valve and stops the flow. The flushometer system requires no storage tank, but uses a high rate of water flow for a very short time. Thus a 22-mm/3⁄4-inch pipe at minimum, or preferably a 29-mm/1-inch pipe, must be used. Water main pressures must be above 2,100 hPa (2.1 bar; 30 psi). The higher water pressure employed by a flushometer valve scours the bowl more efficiently than a gravity-driven system, and fewer blockages typically occur as a result of this higher water pressure. Flushometer systems require approximately the same amount of water as a gravity system to operate.

Bowl design

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The "bowl" or "pan" of a toilet is the receptacle that receives bodily waste. A toilet bowl is most often made of a ceramic, but can sometimes be made of stainless steel or composite plastics. Toilet bowls are mounted in any one of three basic manners: above-floor mounted (pedestal), wall mounted (cantilever), or in-floor mounted (squat toilet).

Within the bowl, there are three main waterway design systems: the siphoning trapped system (found primarily in North American residential installations, and in North American light commercial installations), the non-siphoning trapped system (found in most other installations), and the valve-closet system (found in trains, passenger aircraft, buses, and other such installations around the world). Older style toilets called "washout" toilets are now only found in a few locations.

Siphonic bowls

Single trap siphonic toilet

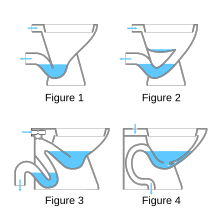

The siphonic toilet, also called "siphon jet" and "siphon wash", is perhaps the most popular design in North America for residential and light commercial toilet installations. All siphonic toilets incorporate an S-shaped waterway.

Standing water in the bowl acts as a barrier to sewer gas coming out of the sewer through the drain, and also as a receptacle for waste. Sewer gas is vented through a separate vent pipe attached to the sewer line. The water in the toilet bowl is connected to the drain by a drainpipe shaped like an extended "S" which curves up behind the bowl and down to the drain. The portion of the channel behind the bowl is arranged as a siphon tube, whose length is greater than the depth of the water in the bowl. The top of the curving tube limits the height of the water in the bowl before it flows down the drain. The waterways in these toilets are designed with slightly smaller diameters than a non-siphonic toilet, so that the waterway will naturally fill up with water each time it is flushed, creating the siphon action.

At the top of the toilet bowl is a rim with many angled drain holes that are fed from the tank, which fill, rinse, and induce swirling in the bowl when it is flushed. Some designs use a large hole in the front of the rim to allow faster filling of the bowl. There may also be a siphon jet hole about 25 mm (1 inch) diameter in the bottom of the toilet bowl trap.

If the toilet is flushed from a tank, a large holding cistern is mounted above the toilet, containing approximately 4.5 to 6 L (1.2 to 1.6 US gallons) of water in modern designs. This tank is built with a large drain 50 to 75 mm (2 to 3 inches) diameter hole at its bottom covered by a flapper valve that allows the water to rapidly leave the holding tank when the flush is activated. Alternatively, water may be supplied directly via a flush valve or "flushometer".

The rapid influx of water into the bowl causes the standing water in the bowl to rise and fill the S-shaped siphon tube mounted in the back of the toilet. This starts the toilet's siphonic action. The siphon action quickly "pulls" nearly all of the water and waste in the bowl and the on-rushing tank water down the drain in about 4–7 seconds —it flushes. When most of the water has drained out of the bowl, the continuous column of water through the siphon is broken when air enters the siphon tube. The toilet then gives its characteristic gurgle as the siphonic action ceases and no more water flows out of the toilet.

A "true siphonic toilet" can be easily identified by the noise it makes. If it can be heard to suck air down the drain at the end of a flush, then it is a true siphonic toilet. If not, then it is either a double trap siphonic or a non-siphonic toilet.

If water is poured slowly into the bowl it simply flows over the rim of the waterway and pours slowly down the drain—thus the toilet does not flush properly.

After flushing, the flapper valve in the water tank closes or the flush valve shuts; water lines and valves connected to the water supply refill the toilet tank and bowl. Then the toilet is again ready for use.

If the forward ("flush") jet connection to the upper inlet in the toilet clogs, poor or no flushing action may result.

Double trap siphonic toilet

The double trap siphonic toilet is a less common type that is exceptionally quiet when flushed. A device known as an aspirator uses the flow of water in a flush to pull air from the cavity between the two traps, reducing the air pressure inside and creating a siphon which pulls water and waste from the toilet bowl. Towards the end of the flush cycle the aspirator ceases being immersed in water, thus allowing air to enter the cavity between the traps and break the siphon, without the gurgling noise, while the final flush water fills the pan.

Non-siphonic bowls

Washdown toilet

Washdown toilets are the most common form of pedestal and cantilever toilets outside the Americas. The bowl has a large opening at the top which tapers down to a water trap at the base. It is flushed from the top by water discharged through a flushing rim or jets. The force of the water flowing into the bowl washes the waste through the trap and into the drains.

Washdown bowls developed from earlier "hopper" closets, which were simple conical bowls connected to a drain. However, waste is typically excreted towards the back of the toilet, rather than the exact center, and the backs of the hoppers were prone to becoming soiled. The modern washdown bowl has a steeply sloping back and a more gently sloping or curving front, so the water trap is off-center, towards the rear of the toilet. With this "eccentric cone" design, most waste drops into the pool of water at the base of the bowl, rather than onto the surface of the toilet. Early washdown closets had a large water area at the base to minimize soiling, which required a large volume of water to clear them effectively. Modern bowls have a smaller area, which reduces the volume of water needed to flush them; however, that water area is always small compared to the water area of a typical North American siphonic bowl, and this makes the washdown bowl prone to soiling.

Washout toilet

Main article: Reverse flush toilet

Washout, or Flachspüler ("shallow flush"), toilets have a flat platform with a shallow pool of water. They are flushed by a jet of water from the back that drives waste into the trap below. From there, the water flow removes it into the sewage system. An advantage of the design is that users will not get splashed from below. Taking of stool samples is also simplified. Washout toilets have a shallow pool of water into which waste is deposited, with a trapped drain just behind this pool. Waste is cleared out from this pool of water by being swept over into the trap (usually either a P-trap or an S-trap) and then beyond into a sewer by water from the flush. Washout pans were among the first types of ceramic toilets invented and since the early 1970s are now only found in a decreasing number of localities in Europe. A washout toilet is a kind of flush toilet which was once predominantly used in Germany, Austria and France. It was patented in Britain by George Jennings in 1852 and remained the standard toilet type in Britain throughout the 19th century.

Examples of this type of toilet can be found in Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, and some regions of Poland, although it is becoming less common.

One disadvantage of this design is that it may require the more intense use of a toilet brush to remove bits of feces that may have left marks on the shelf. Additionally, this design presents the disadvantage of creating a strong lingering odor since the feces are not submerged in water immediately after excretion.

Squat toilet

Main article: Squat toilet

In many parts of Asia, people traditionally use the toilet in a squatting position. This applies to defecation and urination by males and females. Therefore, homes and public washrooms have squat toilets, with the toilet bowl installed in the floor. This has the advantages of not needing an additional toilet seat and also being more convenient for cultures where people use water to wash their genitals instead of toilet paper. However, Western-style toilets that are mounted at sitting height and have a plastic seat have become popular as well. Many public washrooms have both squatting and sitting toilets.

In Western countries, instructions have been put up in some public toilets used by people accustomed to squat toilets, on the correct use of a sitting-style toilet. This is to avoid breaking the toilet or seat if someone attempts to squat on the edges.

The "Anglo-Indian" design used in India allows the same toilet to be used in the sitting or the squatting position.

Valve closet

The valve closet has a valve or flap at the exit of the bowl, often with a watertight seal to retain a pool of water in the pan. When the toilet is flushed, the valve is opened and the water in the pan flows rapidly out of the bowl into the drains, carrying the waste with it.

The earliest type of toilet, the valve closet is now rarely used for water-flush toilet systems. More complicated in design than other toilets, this design has lower reliability and is more difficult to maintain or repair. The most common use for valve closets is now in portable closets for caravans, camping, trains, and aircraft, where the flushing fluid is recycled. This design is also used in train carriages for use in areas where the waste is allowed to be simply dumped between the tracks (the flushing of such toilets is generally prohibited when the train is in a station).

Simple valve closets are used on most older style Russian trains, made in Eastern Germany (Ammendorf factory, design dated probably to the 1950s), employing a pan-like shutter valve at the base of the pan and discharging waste directly onto the trackbed below. Usage of this type of toilet is permitted only while the train is moving, and outside of major cities. These designs are being phased out, together with the old trains, and are being replaced with modern vacuum systems.

The British singer Ian Wallace composed and performed the humorous song "Never Do It at the Station", which mentioned the old-fashioned trackbed dumping toilets which were still in use during the mid-20th century in Britain. The song first advised frugal travelers to save money by avoiding pay toilets in train stations, but also reminded polite passengers not to use the onboard "loo" while the train was stopped at a station.

Low-flow and high-efficiency flush toilets

Main articles: Low flush toilet and Dual flush toiletSince 1994, there is a significant move towards using less water for flushing toilets. This has resulted in the emergence of low flush toilet designs and local or national standards on water consumption for flushing. As an alternative some people modify an existing high flush toilet to use less water by placing a brick or water bottle into the toilet's water tank. Other modifications are often done on the water system itself (such as by using greywater), or a system that pollutes the water less, for more efficient water use.

Urine diversion flush toilets, which were developed in Sweden, save water by using less water, or even no water, for the urine flush compared to about six litres (1.6 US gal) the feces flush.

US standards for new toilets

Pre-1994 residential and pre-1997 commercial flush toilets in the United States typically used 3.4 US gallons (13 L) of water per flush (gpf or lpf). The United States Congress passed the Energy Policy Act of 1992, which mandated that from 1994 common flush toilets use only 1.6 US gallons (6.1 L). In response to the Act, manufacturers produced low-flow toilets, which many consumers did not like because they often required more than one flush to remove solids. People unhappy with the reduced performance of the low-flow toilets resorted to driving across the border to Canada or Mexico or buying salvaged toilets from older buildings. Manufacturers responded to consumers' complaints by improving the toilets. The improved products are generally identified as high efficiency toilets or HETs. HETs possess an effective flush volume of 1.3 US gallons (4.9 L) or less. They may be single-flush or dual-flush. A dual-flush toilet permits selection between different amounts of water for solid or liquid waste. Some HETs are pressure-assisted (or power, pump, or vacuum assisted).

The performance of a flush-toilet may be rated by a Maximum Performance (MaP) score. The low end of MaP scores is 250 (250 grams of simulated fecal matter). The high end of MaP scores is 1,000. A toilet with a MaP score of 1,000 should provide trouble-free service. It should remove all waste with a single flush; it should not plug; it should not harbor any odor; it should be easy to keep clean. The United States Environmental Protection Agency uses a MaP score of 350 as the minimum performance threshold for HETs. 1.6 gpf toilets are also sometimes referred as Ultra Low Flow (ULF).

Methods used to make up for the inadequacies of low flow toilets include using thinner toilet paper, plungers, and adding extra cups of water to the bowl manually.

Maintenance and hygiene

Clogging

If clogging occurs, it is usually the result of an attempt to flush unsuitable items, or as feces size often increases with age or too much toilet paper. Clogging can occur spontaneously due to limescale fouling of the drain pipe, or by overloading the stool capacity of the toilet. Stool capacity varies among toilet designs and is based on the size of the drainage pipe, the capacity of the water tank, the velocity of a flush, and the method by which the water attempts to vacate the bowl of its contents. The size and consistency of the stool is a hard-to-predict contributory factor.

In some countries, clogging has become more frequent due to regulations that require the use of small-tanked low-flush toilets in attempt to conserve water. Designs which increase the velocity of flushed water or improve the travel path can improve low-flow reliability.

Partial clogging is particularly insidious, as it is usually not discovered immediately, but only later by an unsuspecting user trying to flush an incompletely emptied toilet. Overflowing of the water mixed with excrement may then occur, depending on the bowl volume, tank capacity and severity of clogging. For this reason, rooms with flush toilets may be designed as wet rooms, with a second drain on the floor, and a shower head capable of reaching the whole floor area. Common means to remedy clogging include use of a toilet plunger, drain cleaner, or a plumber's snake.

Aerosols

Main article: Toilet plumeA "toilet plume" is the dispersal of microscopic particles into the air as a result of flushing a toilet. Normal use of a toilet by healthy people is considered unlikely to be a major health risk. There is indirect evidence that specific pathogens such as norovirus or SARS coronavirus could potentially be spread through toilet aerosols, but as of 2015 no direct experimental studies had clearly demonstrated or refuted actual disease transmission from toilet aerosols. It has been hypothesized that dispersal of pathogens may be reduced by closing the toilet lid before flushing, and by using toilets with lower flush energy.

History

See also: History of water supply and sanitationPre-modern flush toilet systems

Forms of water flushed latrines have been found to exist since the Neolithic. The oldest neolithic village in Britain, dating from circa 31st century BC, Skara Brae, Orkney, used a form of hydraulic technology for sanitation. The village's design used a stream, and connecting drainage system to wash waste away.

The Mesopotamians introduced the world to clay sewer pipes around 4000 BCE, with the earliest examples found in the Temple of Bel at Nippur and at Eshnunna, utilised to remove wastewater from sites, and capture rainwater, in wells. The city of Uruk hosts the earliest known examples of brick constructed Latrines, both squat and pedestal, from 3200 BCE. Clay pipes were later used in the Hittite city of Hattusa. They had easily detachable and replaceable segments, and allowed for cleaning.

Flushed toilet systems were constructed by people of the Indus Civilization at some places, and later Egyptians and the Minoan civilization did so next, while the latter developed by the second millennium BC flushable pedestal toilets, with examples excavated at Knossos and Akrotiri.

Communal latrines were in use throughout the Roman Empire, feeding into either primary or secondary sewers, from the first through fifth centuries AD. A very well-preserved example are the latrines at Housesteads on Hadrian's Wall in Britain. Such toilets did not flush in the modern sense, but had a continuous stream of running water to wash away waste. With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, these communal toilet systems fell into disuse in Western Europe, though continued in the Eastern Byzantine Roman Empire, with records of toilet pipes being renewed, and sewers repaired.

In February 2023 archeologists in China announced the discovery of the remains of what may be the world's oldest known flush toilet. Broken parts of the 2,400-year-old lavatory, as well as a bent flush pipe, were unearthed among ancient palace ruins in the Yueyang archaeological site in the central city of Xi'an by researchers from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' Institute of Archeology.

Development of the modern flush toilet

In 1596 Sir John Harington (1561–1612) published A New Discourse of a Stale Subject, Called the Metamorphosis of Ajax, describing a forerunner to the modern flush toilet installed at his house at Kelston in Somerset. The design had a flush valve to let water out of the tank, and a wash-down design to empty the bowl. He installed one for his godmother Queen Elizabeth I at Richmond Palace.

With the onset of the Industrial Revolution and related advances in technology, the flush toilet began to emerge into its modern form. A crucial advance in plumbing was the S-trap, invented by the Scottish mechanic Alexander Cumming in 1775, and still in use today. This device uses the standing water to seal the outlet of the bowl, preventing the escape of foul air from the sewer. His design had a sliding valve in the bowl outlet above the trap. Two years later, Samuel Prosser applied for a British patent for a "plunger closet".

Prolific inventor Joseph Bramah began his professional career installing water closets (toilets) that were based on Alexander Cumming's patented design of 1775. He found that the current model being installed in London houses had a tendency to freeze in cold weather. In collaboration with a Mr. Allen, he improved the design by replacing the usual slide valve with a hinged flap that sealed the bottom of the bowl.

He also developed a float valve system for the flush tank. Obtaining the patent for it in 1778, he began making toilets at a workshop in Denmark Street, St Giles. The design was arguably the first practical non-manual flush toilet, and production continued well into the 19th century, used mainly on boats. Thomas Bowdich, an English traveller, visited Kumasi, capital of the Ashanti Empire in 1817 and mentioned that majority of the houses in the city especially those near the king's palace included indoor toilets that were flushed with gallons of boiling water.

Industrial production

It was only in the mid-19th century, with growing levels of urbanisation and industrial prosperity, that the flush toilet became a widely used and marketed invention. This period coincided with the dramatic growth in the sewage system, especially in London, which made the flush toilet particularly attractive for health and sanitation reasons.

George Jennings established a business manufacturing water closets, salt-glaze drainage, sanitary pipes and sanitaryware at Parkstone Pottery in the 1840s, where he popularized the flush toilet to the middle class. At The Great Exhibition at Hyde Park held from 1 May to 15 October 1851, George Jennings installed his Monkey Closets in the Retiring Rooms of The Crystal Palace. These were the first public pay toilets (free ones did not appear until later), and they caused great excitement. During the exhibition, 827,280 visitors paid one penny to use them; for the penny they got a clean seat, a towel, a comb, and a shoe shine. "To spend a penny" became a euphemism, for going to the toilet.

When the exhibition finished and moved to Sydenham, the toilets were to be closed down. However, Jennings persuaded the organisers to keep them open, and the toilet went on to earn over £1,000 a year. He opened the first underground convenience at the Royal Exchange in 1854. He received a patent in 1852 for an improved construction of water-closet, in which the pan and trap were constructed in the same piece, and so formed that there was always a small quantity of water retained in the pan itself, in addition to that in the trap which forms the water-joint. He also improved the construction of valves, drain traps, forcing pumps and pump-barrels. By the end of the 1850s building codes suggested that most new middle-class homes in British cities were equipped with a water closet.

Another pioneering manufacturer was Thomas William Twyford, who invented the single piece, ceramic flush toilet. The 1870s proved to be a defining period for the sanitary industry and the water closet; the debate between the simple water closet trap basin made entirely of earthenware and the very elaborate, complicated and expensive mechanical water closet would fall under public scrutiny and expert opinion. In 1875 the "wash-out" trap water closet was first sold, and was found as the public's preference for basin type water closets. By 1879 Twyford had devised his own type of the "wash out" trap water closet; he titled it the "National", and it became the most popular wash-out water closet.

By the 1880s the free-standing water closet was on sale and quickly gained popularity; the free-standing water closet was able to be cleaned more easily and was therefore a more hygienic water closet. Twyford's "Unitas" model was free-standing and made completely of earthenware. Throughout the 1880s he submitted further patents for improvements to the flushing rim and the outlet. Finally, in 1888 he applied for a patent protection for his "after flush" chamber; the device allowed the basin to be refilled by a lower quantity of clean water in reserve after the water closet was flushed. The modern pedestal "flush-down" toilet was demonstrated by Frederick Humpherson of the Beaufort Works, Chelsea, England in 1885.

The leading companies of the period issued catalogues, established showrooms in department stores and marketed their products around the world. Twyford had showrooms for water closets in Berlin, Germany; Sydney, Australia; and Cape Town, South Africa. The Public Health Act 1875 set down stringent guidelines relating to sewers, drains, water supply and toilets and lent tacit government endorsement to the prominent water closet manufacturers of the day.

Contrary to popular legend, Sir Thomas Crapper did not invent the flush toilet. He was, however, in the forefront of the industry in the late 19th century, and held nine patents, three of them for water closet improvements such as the floating ballcock. In 1880, Thomas Crapper introduced the U-shaped trap. His flush toilets were designed by inventor Albert Giblin, who received a British patent for the "Silent Valveless Water Waste Preventer", a siphon discharge system. Crapper popularized the siphon system for emptying the tank, replacing the earlier floating valve system which was prone to leaks.

Rev. Edward Johns, introduced his Dolphin toilet to the United States at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, attributed to Edward Johns & Co of Armitage, Staffordshire,

"The American slang term for the toilet, “the john,” is said to be derived from the flushing water closets at Harvard University installed in 1735, and emblazoned with the manufacturer’s name, Rev. Edward Johns."

Spread and further developments

Although flush toilets first appeared in Britain, they soon spread to the Continent. The first such examples may have been the three "waterclosets" installed in the new town house of banker Nicolay August Andresen on 6 Kirkegaten in Christiania, insured in January 1859. The toilets were probably imported from Britain, as they were referred to by the English term "waterclosets" in the insurance ledger. Another early watercloset on the European continent, dating from 1860, was imported from Britain to be installed in the rooms of Queen Victoria in Ehrenburg Palace (Coburg, Germany); she was the only one who was allowed to use it. Flush toilets were sold in Batavia, Dutch East Indies in 1872.

In America, the chain-pull indoor toilet was introduced in the homes of the wealthy and in hotels, soon after its invention in England in the 1880s. Flush toilets were introduced in the 1890s. William Elvis Sloan invented the Flushometer in 1906, which used pressurized water directly from the supply line for faster recycle time between flushes. The Flushometer is still in use today in public restrooms worldwide. The vortex-flushing toilet bowl, which creates a self-cleansing effect, was invented by Thomas MacAvity Stewart of Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1907. Philip Haas of Dayton, Ohio, made some significant developments, including the flush rim toilet with multiple jets of water from a ring and the water closet flushing and recycling mechanism similar to those in use today.

The company Caroma in Australia developed the Duoset cistern with two buttons and two flush volumes as a water-saving measure in 1980. Modern versions of the Duoset are now available worldwide, and save the average household 67% of their normal water usage.

Manufacture

A toilet's body is typically made from vitreous china, which starts out as an aqueous suspension of various minerals called a slip. It takes about 20 kg (44 pounds) of slip to make a toilet.

In traditional casting, the slip is poured into the space between plaster of Paris molds. The toilet bowl, rim, tank and tank lid require separate molds. The molds are assembled and set up for filling and the slip-filled molds sit for about an hour after filling. This allows the plaster molds to absorb moisture from the slip, which makes it semi-solid next to the mold surfaces but lets it remain liquid further from the surface of the molds. Then, the workers remove plugs to allow any excess liquid slip to drain from the cavities of the mold (this excess slip is recycled for later use). The drained-out slip leaves hollow voids inside the fixture, using less material to keep it both lighter and easier to fire in a kiln. This molding process allows the formation of intricate internal waste lines in the fixture; the drain's hollow cavities are poured out as slip.

At this point, the toilet parts without their molds look like and are about as strong as soft clay. After about one hour the top core mold (interior of toilet) is removed. The rim mold bottom (which includes a place to mount the holding tank) is removed, and it then has appropriate slanted holes for the rinsing jets cut, and the mounting holes for tank and seat are punched into the rim piece. Valve holes for rapid water entry into the toilet are cut into the rim pieces. The exposed top of the bowl piece is then covered with a thick slip and the still-uncured rim is attached on top of the bowl so that the bowl and hollow rim are now a single piece. The bowl plus rim is then inverted, and the toilet bowl is set upside down on the top rim mold to hold the pieces together as they dry. Later, all the rest of the mold pieces are removed. As the clay body dries further it hardens more and continues to shrink. After a few hours, the casting is self-supporting, and is called greenware.

After the molds are removed, workers use hand tools and sponges to smooth the edges and surface of the greenware, and to remove the mold joints or roughness: this process is called "fettling". For large scale production pieces, these steps may be automated. The parts are then left outside or put in a warm room to dry, before going through a dryer at about 93 °C (199 °F), for about 20–36 hours.

After the surfaces are smoothed, the bowls and tanks are sprayed with glaze of various kinds to get different colors. This glaze is designed to shrink and contract at the same rate as the greenware while undergoing firing. After being sprayed with glaze, the toilet bowls, tanks, and lids are placed in stacks on a conveyor belt or "car" that slowly goes through a large kiln to be fired. The belt slowly moves the glaze-covered greenware into a tunnel kiln, which has different temperature zones inside it starting at about 200 °C (392 °F) at the front, increasing towards the middle to over 1,200 °C (2,190 °F) degrees, and exiting at about 90 °C (194 °F). During the firing in the kiln, the greenware and glaze are vitrified as one solid finished unit. Transiting the kiln takes glaze-covered greenware around 23–40 hours.

After the pieces are removed from the kiln and fully cooled, they are inspected for cracks or other defects. Then, the flushing mechanism may be installed on a one-piece toilet. On a two-piece toilet with a separate tank, the flushing mechanism may only be placed into the tank, with final assembly at installation.

A two-piece attaching seat and toilet bowl lid are typically mounted over the bowl to allow covering the toilet when it is not in use and to provide seating comfort. The seat may be installed at the factory, or the parts may be sold separately and assembled by a plumbing distributor or the installer.

Water usage

The amount of water used by conventional flush toilets is usually a significant portion of personal daily water usage: for example, five 10 L (2.6 US gallons) flushes per day use 50 L (13 US gallons).

Modern low-flush toilet designs allow the use of much less water per flush, 4.5 to 6 L (1.2 to 1.6 US gallons) per flush.

Dual flush toilets allow the user to select between a flush for urine or feces, saving a significant amount of water over conventional units. Dual flush may be accomplished by pushing the flush handle up or down, or a two-segment flush pushbutton may be used whereby pressing the smaller section releases less water.

Flushing with non-potable water sources

Raw water flushing, including seawater flushing, is a method of water conservation, where raw water, such as seawater, is used for flush toilets. Such systems are used in places such as the majority of cities and towns in Hong Kong (see water supply and sanitation in Hong Kong), Gibraltar, and Avalon, California, United States. Heads (on ships) are typically flushed with seawater.

Flush toilets may, if plumbed for it, use greywater (water previously used for washing dishes, laundry and bathing) for flushing rather than drinkable potable water.

Etymology

Further information: Toilet § Names, and Toilet (room) § NamesWater closet

"Water closet" redirects here. For the room in a house with only a toilet, see Toilet (room). For rooms labelled "W.C.", see Public toilet.The word "toilet" initially meant "wash-room", without reference to sanitary facilities. Early indoor toilets were known as garderobes because they were used to store clothes, as the smell of ammonia was found to deter fleas and moths. However, an outhouse was usual until the nineteenth century, and only a few wealthy houses and luxury hotels had indoor toilets connected to drains and sewers. Lidded "chamber pots", kept in specially designed bedside cabinets and used in bedrooms by ladies and invalids, and portable bathtubs, could be emptied and washed in an outhouse.

From the sixteenth century in England, a private room (a closet) with a flushing toilet was referred to as a Water Closet ("WC"), in contrast with an Earth Closet ("EC"), an abbreviation still used in 1960s Oxfordshire cottage sales.

The descriptive terms "wash-down closet" or "water closet" only reached the United States in the 1880s. By 1890 there was increased public awareness of disease and of carelessly disposed human waste being infectious.

In common North American usage, a residential "bathroom" usually contains a toilet, a lavatory, and a bath. However, a commercial bathroom (or “restroom”) contains toilets or urinals but no bath, to the confusion of foreigners. In the UK, Australia and NZ, "bathroom" or bath-room refers to a room with a fixed bathtub and not necessarily a toilet. The terms "bathroom", and "toilet" or "loo" (amongst other euphemisms) indicate distinct functions, although bathrooms may often include toilets.

The term "water closet", refers to a room that has both a toilet and other plumbing fixtures such as a sink or a bathtub. American plumbers and codes use the term "water closet" or "WC" to denote a small room or enclosure with a toilet which is usually located within a larger bathroom that contains other fixtures such as a sink and tub.

Many European languages refer to a toilet as a "water" or "WC". The Royal Spanish Academy Dictionary accepts "váter" as a name for a toilet or bathroom, which is derived from the British term "water closet". France uses the expressions aller aux waters ("to go to the waters") derived from "water closet", and "w.-c." pronounced [ve.se]. Likewise the Romanian word "veceu" pronounced [veˈtʃeu], and the Finnish word "vessa" pronounced [ˈʋesːɑ] derive from a shortened version of the abbreviation. In German, the expression "Klo" pronounced [kloː] (first syllable of "Klosett") is used alongside "WC". In Italian WC pronounced [vutˈtʃi] or [vitˈtʃi], and "water" pronounced [ˈvaːter], are very common terms to refer to the flushing toilet. In Dutch WC pronounced [ˌʋeː ˈseː] is the most common term.

Society and culture

Swirl direction myth

It is a common misconception that when flushed, the water in a toilet bowl swirls one way if the toilet is north of the equator and the other way if south of the equator, due to the Coriolis effect – usually, counter clockwise in the northern hemisphere, and clockwise in the southern hemisphere. In reality, the direction that the water takes is much more determined by the direction that the bowl's rim jets are pointed, and it can be made to flush in either direction in either hemisphere by simply redirecting the rim jets during manufacture. The relative importance of the Coriolis force can be determined by a ratio known as the Rossby number. When this number is much larger than 1, the Coriolis force is insignificant compared to the inertia effects. On the scale of bathtubs and toilets, the Rossby number is on the order of billions, and so the Coriolis effect is too weak to be observed except under carefully controlled laboratory conditions.

Courtesy flush

Since the 1990s, the slang term "courtesy flush" refers to a mid-defecation flush of the toilet as a courtesy to other bathroom users or other prisoners in a cell. A courtesy flush can serve to reduce odor and cover noise.

See also

- Toilets in Japan

- Thomas Maddock, started the American indoor toilet industry

References

- Kagan, Mya. "Where Does the Water Go When I Flush the Toilet?" Kids' Why Questions. Whyzz. Publications LLC, 2011.

- ^ Tilley, Elizabeth; Ulrich, Lukas; Lüthi, Christoph; Reymond, Philippe; Zurbrügg, Chris (2014). Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies (2nd ed.). Duebendorf, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag). ISBN 978-3-906484-57-0.

- "What are Vacuum Toilets?". wiseGEEK. 26 December 2023.

- "How does the toilet in a commercial airliner work?". HowStuffWorks. 1 April 2000.

- "Is the British loo down the pan?". BBC News. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- "The Water Supply (Water Fittings) Regulations 1999". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- "What Toilet Flapper Size Do I Need?". www.korky.com.

- "Waterwise Leaky Loo Position Statement (October 2020)". www.waterwise.org.uk.

- Whewell, Rob (2016). Supply Chain in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Strategic Influences and Supply Chain Responses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-317-04833-6 – via Google Books.

- "The Water Supply (Water Fittings) Regulations 1999". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- "Griffon hydrochasse - pressure tank/cistern" (PDF). www.griffon.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- "Pressure-Assist Technology: How It Works, Where It's Used". www.pmengineer.com. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- "Exploding Toilet Warning: Flushmate recall after toilets blow users out of water". KFOR.com. 21 May 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- "Toilet Flushing System Burst Danger Prompts Massive Recall". NBC New York. 22 October 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- "Point/Counterpoint: Pressure-Assist vs. Gravity Activation Toilets". Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- "EcoNeves Waterflush cistern (Tip Bucket)". www.waterflush.fr/en/. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- US 977562, Sloan, William, "Valve", published 1910-12-06

- Hyden, Stacey M. (17 August 2018), American Standard H2Option Siphonic Toilet Review, Toilet Reviews, retrieved 27 May 2019

- "Swansea University puts up toilet instruction posters". BBC News.

- ""Never Do It At The Station" by Ian Wallace". Playlists.net. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- "Use of brick or water bottle for water conservation". Thedailygreen.com. 1 May 2008. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "42 U.S.C. sec 6295(k)(1)(A)". Codes.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- Perman, Stacy (3 April 2000), "Psst! Wanna Buy An Illegal Toilet?", Time, Windsor, Ontario, archived from the original on 1 December 2008

- ^ "Testing of Popular Toilet Models by Veritec Consulting". Veritec.ca. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Low-flow revolution: As water concerns rise, toilet makers meeting the challenge", Lacrosse Tribune, 26 November 2007; accessed 3 January 2009

- Fleishman, Sandy (5 September 1999). "Mich. Congressman offers measure to flush low-flow toilet laws". Sunday Gazette. Washington Post. p. D3.

- "Low-Flow Toilets All Wet, Some Lawmakers Say". Los Angeles Times. Washington. Associated Press. 28 July 1999.

- Sandbeck, Ellen (2007). Organic Housekeeping: In Which the Non-Toxic Avenger Shows You How to Improve Your Health and That of Your Family, While You Save Time, Money, and, Perhaps, Your Sanity. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-9570-0 – via Google Books.

- Barker, J.; Jones, M.V. (2005). "The potential spread of infection caused by aerosol contamination of surfaces after flushing a domestic toilet". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 99 (2): 339–47. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02610.x. ISSN 1364-5072. PMID 16033465. S2CID 25625899.

- Widdowson, Marc-Alain; Glass, Roger; Monroe, Steve; Beard, R. Suzanne; Bateman, John W.; Lurie, Perrianne; Johnson, Caroline (20 April 2005). "Probable transmission of norovirus on an airplane". JAMA. 293 (15): 1859–60. doi:10.1001/jama.293.15.1859. ISSN 1538-3598. PMID 15840859.

- Ho, Mei-Shang; Monroe, Stephan S.; Stine, Sarah; Cubitt, David; Glass, Roger I.; Madore, H. Paul; Pinsky, Paul F.; Ashley, Charles; Caul, E.O. (21 October 1989). "Viral Gastroenteritis Aboard a Cruise Ship". The Lancet. 334 (8669): 961–65. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90964-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 2571872. S2CID 29429652.

- "Outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) at Amoy Gardens, Kowloon Bay, Hong Kong: Main Findings of the Investigation" (PDF). Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Department of Health. 29 March 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2017.

- ^ Johnson, David L.; Mead, Kenneth R.; Lynch, Robert A.; Hirst, Deborah V.L. (March 2013). "Lifting the lid on toilet plume aerosol: A literature review with suggestions for future research". American Journal of Infection Control. 41 (3): 254–58. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2012.04.330. PMC 4692156. PMID 23040490.

- Jones, R. M.; Brosseau, L. M. (May 2015). "Aerosol transmission of infectious disease". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 57 (5): 501–08. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000000448. PMID 25816216. S2CID 11166016.

- Best, E.L.; Sandoe, J.a.T.; Wilcox, M.H. (1 January 2012). "Potential for aerosolization of Clostridium difficile after flushing toilets: the role of toilet lids in reducing environmental contamination risk". The Journal of Hospital Infection. 80 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2011.08.010. ISSN 1532-2939. PMID 22137761.

- Sarah Smith, Virginia (2007), Clean: a history of personal hygiene and purity, OUP Oxford, p. 28, ISBN 978-0-19-929779-5, retrieved 30 July 2010 – via Google Books

- Childe, V.; Paterson, J.; Thomas, Bryce (30 November 1929). "Provisional Report on the Excavations at Skara Brae, and on Finds from the 1927 and 1928 Campaigns. With a Report on Bones". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 63: 225–280. doi:10.9750/PSAS.063.225.280. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Suddath, Claire (19 November 2009). "A Brief History of Toilets". Time. Time. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Mark, Joshua J. "Skara Brae". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Grant, Walter G.; Childe, V. G. (1938). "A Stone-Age Settlement at the Braes of Rinyo, Rousay, Orkney. (First Report.)". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 72. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Childe, Vere Gordon; Clarke, D. V. (1931). Skara Brae. UK: H.M.S.O., previously: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company, Limited. pp. 12, 20, 28. ISBN 0-11-491755-8 – via Google Books.

- Burke, Joseph (24 April 2017). Fluoridated Water Controversy. Lulu Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-365-91287-0. Retrieved 4 August 2017 – via Google Books.

- Mitchell, Piers D. (3 March 2016). Sanitation, Latrines and Intestinal Parasites in Past Populations. Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-317-05953-0 – via Google Books.

- Wald, Chelsea (26 May 2016). "The secret history of ancient toilets". Nature News. 533 (7604): 456–458. Bibcode:2016Natur.533..456W. doi:10.1038/533456a. PMID 27225101. S2CID 4398699.

- Burney, Charles (19 April 2004). Historical Dictionary of the Hittites. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-6564-5 – via Google Books.

- Yannopoulos, Stavros; Yapijakis, Christos; Kaiafa-Saropoulou, Asimina; Antoniou, George; Angelakis, Andreas N. (2017-02-14). "History of sanitation and hygiene technologies in the Hellenic world". Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development. 7 (2). IWA Publishing: 163–180. doi:10.2166/washdev.2017.178. ISSN 2043-9083.

- Yannopoulos, Stavros; Yapijakis, Christos; Kaiafa-Saropoulou, Asimina; Antoniou, George; Angelakis, Andreas N. (2017). "History of sanitation and hygiene technologies in the Hellenic World". Journal of Water Sanitation and Hygiene for Development. 7 (2): 163–180. doi:10.2166/washdev.2017.178. ISSN 2043-9083.

- "2,400-year-old flush toilet discovered in China could be one of the oldest ever". CNN. 22 February 2023.

- Kinghorn, Jonathan (1986), "A Privvie in Perfection: Sir John Harrington's Water Closet", Bath History, 1: 173–88, ISBN 0-86299-294-X.. Kinghorn supervised a modern reconstruction in 1981, based on the illustrated description by Harington's assistant Thomas Coombe in the New Discourse.

- ^ "From Charles Mackintosh's waterproof to Dolly the sheep: 43 innovations Scotland has given the world". The independent. 30 December 2016.

- Skempton, Alec; et al. (2002). A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland: Vol 1: 1500 to 1830. Thomas Telford. ISBN 0-7277-2939-X.

- Edgerton, Robert B. (2010). The Fall of the Asante Empire: The Hundred-Year War For Africa's Gold Coast. Simon and Schuster. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-4516-0373-6 – via Google Books.

- "Toilet remains from 'spend a penny' exhibition uncovered in Hyde Park". The Royal Parks. 7 June 2016. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- Krinsky, William L. (2 March 1999), "Of Facts and Artifacts", New York Times, retrieved 2 March 2009

- Wilson, Blake (16 December 2008), "Tom the Plumber", New York Times, retrieved 2 March 2009

- "Evolution of Building Elements". Archived from the original on 2014-03-07.

- ^ David J. Eveleigh, 'Twyford, Thomas William (1849–1921)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, May 2009; online edn, May 2011

- Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, Brian (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: In Association with the British Academy. OUP Oxford. ISBN 0-19-861411-X – via Google Books.

- Eveleigh, David J. (2008), Privies and Water Closets, Oxford: Shire Publications, ISBN 978-0-7478-0702-5

- ^ GB 189804990, Giblin, Albert, "Improvements in Flushing Cisterns", published 1898-04-09

- Hart-Davis, Adam, Thomas Crapper – Fact and Fiction, ExNet, retrieved 13 May 2010

- GB 189700724, Crapper, George & Wharam, Robert Marr, "Improvements in or relating to Automatic Syphon Flushing Tanks", published 1897-03-06

- "The Dolphin toilet. Normally attributed to Edward Johns & Co of Armitage, Staffordshire, 1885-1889". Leeds City Museum. Leeds City Council. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- Schmidt, William E. (1992-01-23). "English Bathrooms: Out of the Closet". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- The Pottery & Glass Trades' Journal; Volume 1, Issue 2. J. Everett. 1878. p. 345 – via Google Books.

- "Antique Loo's from the Thomas Crapper Company Collection". jldr.com. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- Edward Johns & Co Ltd (1939-03-14). "GB528110A - Improvements in water closet basins". Google Patents. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

23 October 1940

- "A Brief History of The Flush Toilet". British Association of Urological Surgeons. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- "HISTORY OF MODERN FLUSH TOILETS!". surfacesreporter.com. 5 April 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- "Bataviaasch Handelsblad, 15 November 1872". Bataviaasch Handelsblad. 15 November 1872. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Mario Theriault, Great Maritime Inventions 1833–1950, Goose Lane Editions, 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Norton, Mary Beth; Sheriff, Carol; Blight, David W.; Chudacoff, Howard (2011). A People and a Nation: A History of the United States, Volume II: Since 1865. Cengage Learning. p. 504. ISBN 978-1-133-17188-1 – via Google Books.

- "Tucson lawmaker wants tax credits for water-conserving toilet". Cronkite News Service. 18 January 2008. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- Seawater flushing to be extended to more Hong Kong toilets next year, South China Morning Post, 3 April 2014.

- Leamington Spa Courier, 2 April 1853

- "Phenomena Coriolis". The Oikofuge, 2015-2022. 25 January 2017. Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- "Do bathtubs drain counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere?", The Straight Dope, 15 April 1983

- Anmol, Salim Khan (2020-12-03). Slangs Dictionary of Unconventional English. Sakha Global Books (Sakha Books). p. 166 – via Google Books.

- Praeger, Dave (2009-05-01). Poop Culture: How America Is Shaped by Its Grossest National Product. Feral House. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-932595-62-8 – via Google Books.

External links

[REDACTED] Media related to Flush toilets at Wikimedia Commons

- How Its Made... on YouTube Retrieved 26 September 2011.