| Revision as of 18:33, 24 March 2008 view sourceLittlebutterfly (talk | contribs)533 edits →Rule of the People's Republic of China: removing a paragraph, see talk page.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:03, 20 January 2025 view source Exjerusalemite (talk | contribs)142 edits →Names and etymologies: reverted unsourced change https://en.wikipedia.org/search/?title=Tibet&diff=599171198&oldid=597781637; can't find any source attesting an early Hebrew name for Tibet other than the modern name that came from European languages | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Ethno-cultural region in Asia}} | |||

| {{sprotected|small=yes}} | |||

| {{ |

{{About|the historical ethno-cultural region of Tibet|the current Chinese administrative division|Tibet Autonomous Region|the country that existed from 1912 to 1951|Tibet (1912–1951)}} | ||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=May 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox settlement | |||

| | name = Tibet | |||

| | native_name = བོད་ | |||

| | native_name_lang = bo | |||

| | settlement_type = ] | |||

| | image_map = tibet-claims.jpg | |||

| | map_caption = {{plainlist |style=padding-center:0.6em;text-align:left; | | |||

| * {{nowrap|{{legend2|#ff4040}}{{legend2|#ff9f40}}{{legend2|#ffff40}}{{legend2||}}{{legend2||}}{{legend2||Greater Tibet as claimed by the ]}}}} | |||

| * {{nowrap|{{legend2|}}{{legend2|#ff9f40}}{{legend2|#ffff40}}{{legend2|lightgreen}}{{legend2|#40ffff|}}{{legend2||] as designated by ]}}}} | |||

| * {{nowrap|{{legend2|}}{{legend2|}}{{legend2|#ffff40}}{{legend2|lightgreen}}{{legend2|}}{{legend2||]}}}} | |||

| * {{nowrap|{{legend2|}}{{legend2|}}{{legend2|}}{{legend2|lightgreen}}{{legend2|}}{{legend2||Chinese-controlled, claimed by ] as part of ]}}}} | |||

| * {{nowrap|{{legend2|}}{{legend2|}}{{legend2|}}{{legend2|}}{{legend2|#40ffff}}{{legend2||Indian-controlled, parts claimed by China as ]}}}} | |||

| * {{nowrap|{{legend2|}}{{legend2|}}{{legend2|}}{{legend2|}}{{legend2|}}{{legend2|#4040ff|Other areas historically within the Tibetan cultural sphere}}}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | subdivision_type = Country | |||

| | subdivision_name = {{plainlist| | |||

| *{{BHU}} | |||

| *{{CHN}} | |||

| *{{IND}} | |||

| *{{NPL}} | |||

| *{{PAK}}}} | |||

| | unit_pref = Metric | |||

| | demographics_type1 = Demographics | |||

| | demographics1_footnotes = <!-- for references: use <ref> tags --> | |||

| | demographics1_title1=Ethnicity | |||

| |demographics1_info1 = ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | demographics1_title2=Language | |||

| |demographics1_info2 = ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | blank_name = Main cities | |||

| | blank_info = {{hlist | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |]}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox Chinese | |||

| | pic = Tibet-bo-zh.svg | |||

| | piccap = "Tibet" in the Tibetan (top) and Chinese (bottom) scripts | |||

| | picupright = 0.4 | |||

| | c = 西藏 | |||

| | l = "Western ]" | |||

| | p = Xīzàng | |||

| | w = {{tone superscript|Hsi1-tsang4}} | |||

| | mi = {{IPAc-cmn|x|i|1|.|z|ang|4}} | |||

| | j = sai1 zong6 | |||

| | y = Sāi-johng | |||

| | ci = {{IPAc-yue|s|ai|1|-|z|ong|6}} | |||

| | poj = Se-chōng | |||

| | buc = Să̤-câung | |||

| | teo = Sai-tsăng | |||

| | h = Sî-tshông | |||

| | mc = Sei-dzang | |||

| | tib = {{bo-textonly|བོད}} | |||

| | wylie = Bod | |||

| | zwpy = Poi | |||

| | t = | |||

| | s = | |||

| | altname = | |||

| | bpmf = ㄒㄧ ㄗㄤˋ | |||

| | tp = Sizàng | |||

| }} | |||

| {{SpecialChars | |||

| | image = Standard Tibetan name.svg | |||

| | special = ] | |||

| | fix = Help:Multilingual support (Indic) | |||

| | characters = Tibetan characters | |||

| | error = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Tibet''' ({{IPAc-en|audio=En-us-Tibet.ogg|t|ᵻ|ˈ|b|ɛ|t}}; {{bo|t=བོད|l=pʰøːʔ˨˧˩|p=Bod}} ''Böd''; {{zh|s=藏区||p=Zàngqū}}), or '''Greater Tibet''',<ref>{{cite book |last1=Wang |first1=Lixiong |editor1-last=Sautman |editor1-first=Barry |editor2-last=Teufel Dryer |editor2-first=June |title=Contemporary Tibet: Politics, Development and Society in a Disputed Region |date=2005 |publisher=Routledge |page=114 |chapter=Indirect Representation Versus a Democratic System Relative Advantages for Resolving the Tibet |quote=...the whole of Tibet, sometimes called Greater Tibet.}}</ref> is a region in the western part of ], covering much of the ] and spanning about {{convert|2500000|km2|abbr=on}}. It is the homeland of the ]. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups such as ], ], ], ], ], ], and since the 20th century ] and ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Wang |first1=Ju-Han Zoe |last2=Roche |first2=Gerald |date=March 16, 2021 |title=Urbanizing Minority Minzu in the PRC: Insights from the Literature on Settler Colonialism |url=https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/14776011 |journal=] |language=en |volume=48 |issue=3 |pages=593–616 |doi=10.1177/0097700421995135 |issn=0097-7004 |s2cid=233620981}}</ref> Tibet is the highest region on Earth, with an average elevation of {{convert|4380|m|sigfig=2|abbr=on}}.<ref>{{cite web |title=Altitude sickness may hinder ethnic integration in the world's highest places |url=https://www.princeton.edu/news/2013/07/01/altitude-sickness-may-hinder-ethnic-integration-worlds-highest-places |publisher=Princeton University |date=July 1, 2013 |access-date=March 6, 2021 |archive-date=March 18, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210318150542/https://www.princeton.edu/news/2013/07/01/altitude-sickness-may-hinder-ethnic-integration-worlds-highest-places |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://oak.ucc.nau.edu/wittke/Tibet/Plateau.html |title=Geology of the Tibetan Plateau |last=Wittke |first=J.H. |date=February 24, 2010|access-date=March 29, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190523070800/http://oak.ucc.nau.edu/wittke/Tibet/Plateau.html|archive-date=May 23, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> Located in the ], the highest elevation in Tibet is ], Earth's highest mountain, rising {{Convert|8,848|m|ft|abbr=on|sigfig=2}} above sea level.<ref>{{Cite web |last=US Department of Commerce |first=National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |title=What is the highest point on Earth as measured from Earth's center? |url=https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/highestpoint.html#:~:text=Mount%20Everest,%20located%20in%20Nepal,But%20the%20summit%20of%20Mt.|access-date=November 12, 2021 |website=oceanservice.noaa.gov |language=EN-US|archive-date=May 28, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160528130315/https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/highestpoint.html#:~:text=Mount%20Everest,%20located%20in%20Nepal,But%20the%20summit%20of%20Mt.|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| {| class="toccolours" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" style="float: right; margin: 0 0 1em 1em; width: 340px; border-collapse: collapse; font-size: 85%;" bgcolor=#eeeeee | |||

| |- | |||

| |height=3px colspan=10| | |||

| |- align="center" | |||

| | colspan="10" | <div style="position:relative; margin: 0 0 0 0; border-collapse: collapse; border="1" cellpadding="0"> | |||

| ]</div> | |||

| |- | |||

| | width=20% height=15px bgcolor=#ffffff align="right"|] ] ] | |||

| | height=15px bgcolor=#ffffff |<small>Historic Tibet as claimed by Tibetan exile groups</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| | width=25% height=15px bgcolor=#ffffff align="right"|] ] ] ] | |||

| | height=15px bgcolor=#ffffff |<small>Tibetan areas designated by the ]</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| | width=25% height=15px bgcolor=#ffffff align="right"|] ] | |||

| | height=15px bgcolor=#ffffff |<small>] (actual control)</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| | width=25% height=15px bgcolor=#ffffff align="right"|] | |||

| | height=15px bgcolor=#ffffff |<small>Claimed by ] as part of ]</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| | width=25% height=15px bgcolor=#ffffff align="right"|] | |||

| | height=15px bgcolor=#ffffff |<small>Claimed by PRC as part of ]</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| | width=25% height=15px bgcolor=#ffffff align="right"|] | |||

| | height=15px bgcolor=#ffffff |<small>Other areas historically within Tibetan cultural sphere</small> | |||

| |} | |||

| '''Tibet''' is a ] in ] and the home to the indigenous ]. With an average ] of 4,900 ]s (16,000 ]), it is the highest region on Earth and is commonly referred to as the "Roof of the World." Geographically, ] and ''Encyclopædia Britannica''<ref name=Britannica></ref> consider Tibet to be part of ], while several academic organizations ] consider it part of ]. | |||

| The ] emerged in the 7th century. At its height in the 9th century, the Tibetan Empire extended far beyond the Tibetan Plateau, from the ] and ] in the west, to ] and ] in the southeast. It then divided into a variety of territories. The bulk of western and central Tibet (]) was often at least nominally unified under a series of Tibetan governments in ], ], or nearby locations. The eastern regions of ] and ] often maintained a more decentralized indigenous political structure, being divided among a number of small principalities and tribal groups, while also often falling under Chinese rule; most of this area was eventually annexed into the Chinese provinces of ] and ]. The current borders of Tibet were generally established in the 18th century.<ref>Goldstein, Melvyn, C.,'' Change, Conflict and Continuity among a Community of Nomadic Pastoralist: A Case Study from Western Tibet, 1950–1990'', 1994: "What is Tibet? – Fact and Fancy", pp. 76–87</ref> | |||

| Many parts of the region were united in the seventh century by King ]. In 1751, the (]) government, which ruled China from 1644 to 1912, established the Dalai Lama as both the spiritual leader and political leader of Tibet who led a government (Kashag) with four Kalöns in it.<ref name="Wang 170-3">Wang Jiawei, "The Historical Status of China's Tibet", 2000, pp. 170–3</ref> Between the 17th century and 1951, the Dalai Lama and his regents were the predominant political power administering religious and administrative authority<ref name="Grunfeld"/> over large parts of Tibet from the traditional capital ]. | |||

| Following the ] against the ] in 1912, Qing soldiers were disarmed and escorted out of Ü-Tsang, but it has been constitutionally claimed by the ] as the ]. The ] ] in 1913, although it was neither recognised by the ] nor any foreign power.<ref>Clark, Gregory, "''In fear of China''", 1969, saying: ' ''Tibet, although enjoying independence at certain periods of its history, had never been recognized by any single foreign power as an independent state. The closest it has ever come to such recognition was the British formula of 1943: ], combined with ] and the right to enter into diplomatic relations.'' '</ref> Lhasa later took control of western ] as well. The region maintained its autonomy until 1951 when, following the ], it was occupied and ]. The entire plateau came under PRC administration. The Tibetan government was abolished after the failure of the ].<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-14533879 |title=Q&A: China and the Tibetans |date=August 15, 2011 |work=BBC News|access-date=May 17, 2017 |language=en-GB|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180716034707/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-14533879|archive-date=July 16, 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> Today, China governs western and central Tibet as the ] while the eastern areas are now mostly ]s within Qinghai, ], ] and Sichuan provinces. | |||

| Tibet proclaimed its independence from China in 1911, right before the fall of the Qing government. However, "at no time did any western power come out in favor of its independence or grant it diplomatic recognition.”<ref> Virtual Tibet: Searching for Shangri-La from the Himalayas to Hollywood, page 24</ref> The ] (PRC), citing historical records and the Seventeen Point Agreement signed by the Tibetan government in 1951, claims Tibet as a part of China (with a small part, depending on definitions, controlled by ]). Currently every country in the world recognizes China's sovereignty over Tibet. Dalai Lama, the head of the Tibetan government in exile, does not reject China’s sovereignty over Tibet: “” | |||

| The ]<ref name="lee">{{cite web |url=http://sites.google.com/site/tibetanpoliticalreview/articles/tibetsonlyhopelieswithin |title=Tibet's only hope lies within |first=Peter |last=Lee |author-link = |date=May 7, 2011 |publisher=The Asia Times |access-date = May 10, 2011 |quote=Robin described the region as a cauldron of tension. ] still were infuriated by numerous arrests in the wake of the 2008 protests. But local Tibetans had not organized themselves. 'They are very angry at the Chinese government and the Chinese people,' Robin said. 'But they have no idea what to do. There is no leader. When a leader appears and somebody helps out they will all join.' We ... heard tale after tale of civil disobedience in outlying ]. In one village, Tibetans burned their Chinese flags and hoisted the banned Tibetan Snow Lion flag instead. Authorities ... detained nine villagers ... One nomad ... said 'After I die ... my sons and grandsons will remember. They will hate the government.' |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20111228180221/http://sites.google.com/site/tibetanpoliticalreview/articles/tibetsonlyhopelieswithin |archive-date = December 28, 2011 |url-status = live |df=mdy-all}}</ref> is principally led by the ].<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/country_profiles/4152353.stm |work=BBC News |title=Regions and territories: Tibet |date=December 11, 2010 | access-date=April 22, 2011 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110422064415/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/country_profiles/4152353.stm | archive-date=April 22, 2011 | url-status=live |df=mdy-all}}</ref> Human rights groups have accused the Chinese government of abuses of ], including ], arbitrary arrests, and religious repression, with the Chinese government tightly controlling information and denying external scrutiny.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/19/world/asia/19tibet.html |title=China Adds to Security Forces in Tibet Amid Calls for a Boycott |last=Wong |first=Edward |date=February 18, 2009 |work=The New York Times|access-date=May 17, 2017 |issn=0362-4331|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170616034115/http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/19/world/asia/19tibet.html|archive-date=June 16, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.hrw.org/news/2008/03/19/china-tibetan-detainees-serious-risk-torture-and-mistreatment |title=China: Tibetan Detainees at Serious Risk of Torture and Mistreatment |date=March 19, 2008|access-date=March 7, 2023|archive-date=March 7, 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230307190141/https://www.hrw.org/news/2008/03/19/china-tibetan-detainees-serious-risk-torture-and-mistreatment|url-status=live}}</ref> While there are conflicting reports on the scale of human rights violations, including allegations of cultural genocide and the ], widespread suppression of Tibetan culture and dissent continues to be documented. | |||

| ==Definitions of Tibet== | |||

| ] used intermittently between 1912 and 1950. This version was introduced by the 13th Dalai Lama in 1912. The flag is outlawed in the ].]] | |||

| The dominant ] is ]; other religions include ], an ] similar to Tibetan Buddhism,<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.religionfacts.com/bon |title=Bon |work=ReligionFacts|access-date=May 17, 2017 |language=en|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170509140454/http://www.religionfacts.com/bon|archive-date=May 9, 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> ], and ]. Tibetan Buddhism is a primary influence on the ], ], and ] of the region. ] reflects ] and ] influences. ] are roasted ], ] meat, and ]. With the growth of tourism in recent years, the service sector has become the largest sector in Tibet, accounting for 50.1% of the local GDP in 2020.<ref>{{Cite web |title=2020年西藏自治区国民经济和社会发展统计公报 |url=https://www.neac.gov.cn/seac/xxgk/202108/1150390.shtml |website=State Ethnic Affairs Commission |access-date=April 24, 2022 |archive-date=March 20, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220320025534/https://www.neac.gov.cn/seac/xxgk/202108/1150390.shtml |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| When the People's Republic of China (PRC) refers to Tibet, it means the ] (TAR): a ]-level entity which, according to the territorial claims of the PRC, includes ]. The TAR covers the ]'s former domain, consisting of Ü-Tsang and western Kham, while Amdo and eastern Kham are part of ], ], ], and ].<ref name=ataglance/> | |||

| == Names and etymologies == | |||

| When the ] and the Tibetan refugee community abroad refer to Tibet, they mean the areas consisting of the traditional provinces of ], ], and ], but excluding ], ], and ] that have also formed part of the Tibetan cultural sphere.<ref name=ataglance>{{Citation| publisher=The Government of Tibet in Exile| title=Tibet at a Glance| year=1996| url =http://www.tibet.com/glance.html| accessdate=2008-03-14}}</ref> | |||

| ] (8th century) overlaid on a map of modern borders]] | |||

| {{Main|Etymology of Tibet}} | |||

| The ] name for their land, ''Bod'' ({{Bo-textonly|བོད་}}), means 'Tibet' or ']', although it originally meant the central region around ], now known in Tibetan as ] ({{Bo-textonly|དབུས}}).{{Citation needed|reason=Please, provide a source for this statement|date=June 2017}} The ] pronunciation of ''Bod'' ({{IPA|bo|pʰøʔ˨˧˨|}}) is transcribed as: ''Bhö'' in ]; ''Bö'' in the ]; and ''Poi'' in ]. Some scholars believe the first written reference to ''Bod'' ('Tibet') was the ancient Bautai people recorded in the Egyptian-Greek works '']'' (1st century CE) and '']'' (], 2nd century CE),<ref>Beckwith (1987), pg. 7</ref> itself from the ] form ''Bhauṭṭa'' of the Indian geographical tradition.<ref>Étienne de la Vaissière, "The Triple System of Orography in Ptolemy's Xinjiang", ''Exegisti Monumenta: Festschrif in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams'', eds. Werner Sundermann, Almut Hintze & François de Blois (Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz, 2009), 532.</ref> | |||

| The difference in definition is a major source of dispute. The distribution of Amdo and eastern Kham into surrounding provinces was initiated by the ] during the 18th century and has been continuously maintained by successive Chinese governments. Tibetan exiles, in turn, consider the maintenance of this arrangement from the 18th century as part of a ] policy.{{Fact|date=August 2007}} | |||

| The best-known medieval Chinese name for Tibet is ''Tubo'' ({{zh|s={{linktext|吐蕃}}|links=no}}; or {{zh|hp=Tǔbō|links=no|c=|s=|t=|labels=no}}, {{linktext|lang=zh|土蕃}} or {{lang|zh|Tǔfān}}, {{linktext|lang=zh|土番}}). This name first appears ] as {{lang|zh-hans-CN|土番}} in the 7th century (]) and as {{lang|zh-hans-CN|吐蕃}} in the 10th century ('']'', describing 608–609 emissaries from Tibetan King ] to ]). In the ] language spoken during that period, as reconstructed by ], {{lang|zh-hans-CN|土番}} was pronounced ''thu{{Smallcaps|x}}-phjon'', and {{lang|zh-hans-CN|吐蕃}} was pronounced ''thu{{Smallcaps|x}}-pjon'' (with the ''{{Smallcaps|x}}'' representing a '']'' ]).<ref name="Baxter">{{cite web |url=http://www-personal.umich.edu/~wbaxter/etymdict.html |title=An Etymological Dictionary of Common Chinese Characters |last1=Baxter |first1=William H. |date=March 30, 2001 |access-date=April 16, 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110411153909/http://www-personal.umich.edu/~wbaxter/etymdict.html |archive-date=April 11, 2011}}</ref> | |||

| == Name == | |||

| Tibetans call their homeland ''Bod'' (<font face="jomolhari">བོད་</font>), pronounced in ] dialect. It is first attested in the geography of ] as βαται (''batai'')<ref>Beckwith, C. U. of Indiana Diss. 1977</ref>. In Nepal, Tibet is known as ''Bhot''.{{Fact|date=March 2008}} | |||

| Other pre-modern Chinese names for Tibet include: | |||

| * ''Wusiguo'' ({{zh|s=烏斯國|hp=Wūsīguó|links=no}}; ] Tibetan: ''dbus'', ], {{IPA|bo|wyʔ˨˧˨|}}); | |||

| ] | |||

| * ''Wusizang'' ({{zh|s=烏斯藏|hp=wūsīzàng|links=no}}, cf. Tibetan: ''dbus-gtsang'', ]); | |||

| The PRC's Chinese name for Tibet, 西藏 (Xīzàng), is a phonetic transliteration derived from the region called ] (western ]). The Chinese name originated during the ] of China, ca. 1700. It can be broken down into ''xī'' 西 ("west"), and “zàng” 藏 (from ], but also literally “Buddhist scripture,” or “storage” or possibly "treasure"<ref>See ] for more information on the relationship between literal meanings and sound transliterations.</ref>). The pre-1700s historic Chinese term for Tibet was "{{linktext|吐蕃}}". In modern ], the first character is pronounced ''tǔ''. The second character is normally pronounced ''fān''; in the context of references to Tibet, most authorities say that it should be pronounced ''bō'' (making the word "Tubo"), while some authorities make no distinction between the general pronunciation and that in the Tibetan context, making the word "Tufan".<ref>"现代汉语词典","遠東漢英大辭典".</ref> Its reconstructed Medieval Chinese pronunciation is /t'obw{{IPA|ǝ}}n/, which comes from the ] word for “heights” which is also the origin of the English term ''Tibet''.<ref name="Behr">Behr, W., (book review), ''Oriens'' 34 (1994): 557–564.</ref><ref name="Sellheim">Sellheim, R. "''Oriens - Journal of the International Society for Oriental Research: 1994''". ], 1994. </ref> When expressing themselves in Chinese, many exiled Tibetans, including the Dalai Lama's government in ], now use the term 吐博 Tǔbó. Although the second character is not historically accurate, it has the correct pronunciation (whereas ambiguity attends the pronunciation of 蕃), and thus 吐博 is deemed by some to be a more appropriate way to write ''Tibet'' in Chinese. | |||

| * ''Tubote'' ({{zh|s=圖伯特|hp=Túbótè|links=no}}); and | |||

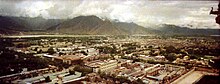

| ] in 2005]] | |||

| * ''Tanggute'' ({{zh|s=唐古忒|hp=Tánggǔtè|links=no}}, cf. ]). | |||

| American ] ] has argued in favor of a recent tendency by some authors writing in Chinese to revive the term ''Tubote'' ({{zh|s=图伯特|t=圖伯特|hp=Túbótè|links=no}}) for modern use in place of ''Xizang'', on the grounds that ''Tubote'' more clearly includes the entire ] rather than simply the ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://sites.google.com/site/tibetanpoliticalreview/articles/tubotetibetandthepowerofnaming |title=Tubote, Tibet, and the Power of Naming |website=Tibetan Political Review |author=Elliot Sperling | access-date=July 31, 2018 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160328133904/https://sites.google.com/site/tibetanpoliticalreview/articles/tubotetibetandthepowerofnaming | archive-date=March 28, 2016 | url-status=live |df=mdy-all}}</ref> | |||

| The government of the ] equates Tibet with the ] (TAR). As such, the name ''Xīzàng'' is equated with the TAR. In order to refer to non-TAR Tibetan areas, or to all of cultural Tibet, the term 藏区 Zàngqū (literally, "ethnic Tibetan areas") is used. However, Chinese-language versions of pro-Tibetan independence websites, such as the ], the ], and ] use 西藏 (“Xīzàng”), not 藏区 ("Zàngqū"), to mean historic Tibet. | |||

| The English word ''Tibet'' or ''Thibet'' dates back to the 18th century.<ref>The word ''Tibet'' was used in the context of the first British mission to this country under ] in 1774. | |||

| Some English-speakers reserve ''Xīzàng'', the Chinese word transliterated into English, for the TAR, to keep the concept distinct from that of historic Tibet.{{Fact|date=November 2007}} | |||

| See ], ed. 1971. ''Narratives of the Mission of George Bogle to Tibet and the Journey of Thomas Manning to Lhasa''. New Delhi: Manjushri Publishing House.</ref> ] generally agree that "Tibet" names in European languages are ]s from ] {{transliteration|ar|ALA|Ṭībat}} or {{transliteration|ar|ALA|Tūbātt}} ({{langx|ar|طيبة، توبات}}), itself deriving from ] ''{{lang|trk|Töbäd}}'' (plural of {{lang|trk|töbän}}), literally 'The Heights'.<ref>Behr, Wolfgang, 1994. "." Pp. 558–59 in ''Oriens'' 34, edited by R. Sellheim. Leiden: E.J. Brill. Archived from the {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230326164813/https://books.google.com/books?id=NHN6KTAVR28C&dq=t%C3%83%C2%B6p%C3%83%C2%BCt&pg=PA559 |date=March 26, 2023 }} on October 16, 2015.</ref> | |||

| The character 藏 (zàng) has been used in transcriptions referring to Tsang as early as the ], if not earlier, though the modern term ''Xizang'' (western Tsang) was devised in the 18th century. The Chinese character 藏 (Zàng) has also been generalized to refer to all of Tibet, including other concepts related to Tibet such as the ] (藏文, Zàngwén) and the Tibetan people (藏族, Zàngzú). | |||

| == Language == | |||

| According to ], the Great Indian Epic, term ] is ''Trivishtham''. In ], Tri means three and ''Vishtham'' represents the ] powers of Lord ]. As per ], ]s are abode of ], the region is acclaimed to be ] become ] in colloqial ] and became ] in ] Language which eventually turned as ] | |||

| {{Main|Standard Tibetan}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Linguists generally classify the ] as a ] language of the ] family, although the boundaries between 'Tibetan' and certain other ]n languages can be unclear. According to ]:<blockquote> | |||

| From the perspective of historical linguistics, Tibetan most closely resembles ] among the major languages of Asia. Grouping these two together with other apparently related languages spoken in the ]n lands, as well as in the highlands of Southeast Asia and the Sino-Tibetan frontier regions, linguists have generally concluded that there exists a Tibeto-Burman family of languages. More controversial is the theory that the Tibeto-Burman family is itself part of a larger language family, called ], and that through it Tibetan and Burmese are distant cousins of Chinese.<ref>Kapstein 2006, pg. 19</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| ] attending a horse festival]] | |||

| ===In English=== | |||

| The language has numerous regional dialects which are generally not mutually intelligible. It is employed throughout the Tibetan plateau and ] and is also spoken in parts of ] and northern India, such as ]. In general, the dialects of central Tibet (including Lhasa), ], ] and some smaller nearby areas are considered Tibetan dialects. Other forms, particularly ], ], ], and ], are considered by their speakers, largely for political reasons, to be separate languages. However, if the latter group of Tibetan-type languages are included in the calculation, then 'greater Tibetan' is spoken by approximately 6 million people across the Tibetan Plateau. Tibetan is also spoken by approximately 150,000 exile speakers who have fled from modern-day Tibet to India and other countries.{{citation needed|date=January 2023}} | |||

| The English word ''Tibet'', like the word for Tibet in most European languages, is derived from the ] word ''Tubbat''.<ref name="Partridge">Partridge, Eric, ''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'', New York, 1966, p. 719.</ref> This word is derived via ] from the ] word ''Töbäd'' (plural of ''Töbän''), meaning "the heights".<ref name="Behr" /><ref name="Sellheim" /> In Medieval Chinese, ] (pronounced ''tǔbō''), is derived from the same Turkic word.<ref name="Behr" /> 吐蕃 was pronounced /t'o-bw{{IPA|ǝ}}n/ in Medieval times. | |||

| Although spoken Tibetan varies according to the region, the written language, based on ], is consistent throughout. This is probably due to the long-standing influence of the Tibetan empire, whose rule embraced (and extended at times far beyond) the present Tibetan linguistic area, which runs from ] in the west to ] and ] in the east, and from north of ] south as far as Bhutan. The Tibetan language has its ] which it shares with ] and ], and which is derived from the ancient Indian ].<ref>Kapstein 2006, p. 22.</ref> | |||

| The exact derivation of the name is, however, unclear. Some scholars believe that the named derived from that of a people who lived in the region of northeastern Tibet and were referred to as ''Töbüt'' or ''Tübüt''. This was the form adapted by the Muslim writers who rendered it ''Tübbett'', ''Tibbat'', etc., from as early as the 9th century, and it then entered European languages from the reports of the medieval European accounts of ], ], ] and the ] monk ].<ref>Stein, R. A. ''Tibetan Civilization'' (1922). English edition with minor revisions in 1972 Stanford University Press, p. 31. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN 0-8047-0901-7.</ref> | |||

| Starting in 2001, the local ]s of Tibet were standardized, and ] is now being promoted across the country. | |||

| ] scholars favor the theory that "Tibet" is derived from ''tǔbō''.<ref name="Partridge"/><ref>China Tibet Information Center </ref> | |||

| The first Tibetan-English dictionary and grammar book was written by ] in 1834.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230326164813/https://books.google.com/books?id=a78IAAAAQAAJ&q=csoma |date=March 26, 2023 }}.</ref> | |||

| ==Language== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The ] are spoken throughout the Tibetan plateau, ], and parts of ] and northern ]. Spoken Tibetan includes numerous regional dialects which, in many cases, are not mutually intelligible. Moreover, the boundaries between ''Tibetan'' and certain other Himalayan languages are sometimes unclear. In general, the dialects of central Tibet (Ü-Tsang, including Lhasa), ], ], and some smaller nearby areas are considered Tibetan dialects. The languages of some groups outside modern Tibet, such as ], ], ], and ], are more distant varieties descended from archaic Tibetan, and which bear varying degrees of similarity to modern Tibetan. Using this broader grouping of Tibetan dialects and forms, the Tibetan language "family" is spoken by approximately 6 million people across the ]. Tibetan is also spoken by approximately 150,000 exiles who have fled from modern-day Tibet to ] and other countries. | |||

| The Tibetan language has its own ], which is part of the ] of scripts.<ref>Omniglot, </ref> | |||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|History of Tibet}} | ||

| {{ |

{{Further|History of European exploration in Tibet|Foreign relations of Tibet}} | ||

| <!-- PLEASE CROSS CHECK CHANGES HERE WITH TEXT AT ] -->=== Early history === | |||

| {{see|History of European exploration in Tibet|Foreign relations of Tibet}} | |||

| {{Main|Neolithic Tibet|Zhangzhung|Pre-Imperial Tibet}} | |||

| <!-- PLEASE CROSS CHECK CHANGES HERE WITH TEXT AT ] --> | |||

| ], the first ] of ], is considered to have attained ] near ] in Tibet in Jain tradition.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y4aVRLGhf-8C&q=Rishabhdev+Tibet&pg=RA1-PA273 |title=Faith & Philosophy of Jainism |isbn=978-81-7835-723-2 |last1=Jain |first1=Arun Kumar |year=2009 |publisher=Gyan Publishing House| access-date=October 18, 2020| archive-date=April 14, 2023| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230414142806/https://books.google.com/books?id=y4aVRLGhf-8C&q=Rishabhdev+Tibet&pg=RA1-PA273| url-status=live}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ]]]Humans inhabited the Tibetan Plateau at least 21,000 years ago.<ref name="Zhao">{{cite journal |last1=Zhao |first1=M |last2=Kong |first2=QP |last3=Wang |first3=HW |last4=Peng |first4=MS |last5=Xie |first5=XD |last6=Wang |first6=WZ |last7=Jiayang |first7=Duan JG |last8=Cai |first8=MC |last9=Zhao |first9=SN | last10 = Cidanpingcuo | first10 = Tu YQ |last11=Wu |first11=SF |last12=Yao |first12=YG |last13=Bandelt |first13=HJ |last14=Zhang |first14=YP |year=2009 |title=Mitochondrial genome evidence reveals successful Late Paleolithic settlement on the Tibetan Plateau |journal=Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A |volume=106 |issue=50 |pages=21230–21235 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0907844106 |pmid=19955425 |pmc=2795552 |bibcode=2009PNAS..10621230Z | doi-access = free | issn = 0027-8424}}</ref> This population was largely replaced around 3,000 ] by ] immigrants from northern China, but there is a partial genetic continuity between the Paleolithic inhabitants and contemporary Tibetan populations.<ref name="Zhao" /> | |||

| The earliest Tibetan historical texts identify the ] as a people who migrated from the Amdo region into what is now the region of ] in western Tibet.<ref name="Norbu">Norbu 1989, pp. 127–128</ref> Zhang Zhung is considered to be the original home of the ] religion.<ref name="Hoffman">Helmut Hoffman in McKay 2003 vol. 1, pp. 45–68</ref> By the 1st century BCE, a neighboring kingdom arose in the ], and the Yarlung king, ], attempted to remove the influence of the Zhang Zhung by expelling the Zhang's Bön priests from Yarlung.<ref name="Karmay">{{cite book |last1=Karmay |first1=Samten Gyaltsen |title=The Treasury of Good Sayings: A Tibetan History of Bon |date=2005 |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass Publisher |isbn=978-81-208-2943-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vhetCgcQReIC&pg=PA66 |language=en |pages=66ff |access-date=December 3, 2022 |archive-date=December 3, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221203202548/https://books.google.com/books?id=vhetCgcQReIC&pg=PA66 |url-status=live}}</ref> He was assassinated and Zhang Zhung continued its dominance of the region until it was annexed by Songtsen Gampo in the 7th century. Prior to ], the kings of Tibet were more mythological than factual, and there is insufficient evidence of their existence.<ref>]: ''Extract from "The Yar Lun Dynasty"'', in: ''The History of Tibet'', ed. Alex McKay, Vol. 1, London 2003, p. 147; Richardson, Hugh: ''The Origin of the Tibetan Kingdom'', in: ''The History of Tibet'', ed. Alex McKay, Vol. 1, London 2003, p. 159 (and list of kings p. 166-167).</ref> | |||

| ===Pre-History=== | |||

| Chinese and the "proto-Tibeto-Burman" language may have split sometime before 4000 BC, when the Chinese began growing ] in the Yellow River valley while the Tibeto-Burmans remained nomads. Tibetan split from Burman around 500 AD.<ref name="VanDriem">Van Driem, George "Tibeto-Burman Phylogeny and Prehistory: Languages, Material Culture and Genes".</ref><ref name="Bellwood">Bellwood, Peter & Renfrew, Colin (eds) ''Examining the farming/language dispersal hypothesis'' (2003), Ch 19.</ref> | |||

| === Tibetan Empire === | |||

| Prehistoric ] ] and burial complexes have recently been found on the ] plateau but the remoteness of the location is hampering archaeological research. The initial identification of this culture is as the ] which is described in ancient Tibetan texts and is known as the original culture of the ] religion. | |||

| {{main|Tibetan Empire}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The history of a unified Tibet begins with the rule of ] (604–650{{nbsp}}CE), who united parts of the ] Valley and founded the Tibetan Empire. He also brought in many reforms, and Tibetan power spread rapidly, creating a large and powerful empire. It is traditionally considered that his first wife was the Princess of Nepal, ], and that she played a great role in the establishment of Buddhism in Tibet. In 640, he married ], the niece of the Chinese emperor ].<ref>Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2011). 'The First Tibetan Empire' in: ''China's Ancient Tea Horse Road''. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B005DQV7Q2</ref> | |||

| Under the next few Tibetan kings, Buddhism became established as the state religion and Tibetan power increased even further over large areas of ], while major inroads were made into Chinese territory, even reaching the ]'s capital ] (modern ]) in late 763.<ref>Beckwith 1987, pg. 146</ref> However, the Tibetan occupation of Chang'an only lasted for fifteen days, after which they were defeated by Tang and its ally, the Turkic ]. | |||

| ===Tibetan Empire=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| A series of ] ruled Tibet from the 7th to the 11th century. At times, Tibetan rule may have extended as far south as ] and as far north as ].{{Fact|date=August 2007}} | |||

| The ] (in ] and neighbouring regions) remained under Tibetan control from 750 to 794, when they turned on their Tibetan overlords and helped the Chinese inflict a serious defeat on the Tibetans.<ref>Marks, Thomas A. (1978). "Nanchao and Tibet in South-western China and Central Asia." ''The Tibet Journal''. Vol. 3, No. 4. Winter 1978, pp. 13–16.</ref> | |||

| Tibet appeared in an ancient Chinese historical text where it is referred to as ''fa''. The first incident from recorded Tibetan history which is confirmed externally occurred when King ] sent an ambassador to the Chinese court in the early 7th century.<ref name="Beckwith1977">Beckwith, ''C. Uni. of Indiana Diss.'', 1977</ref> | |||

| In 747, the hold of Tibet was loosened by the campaign of general ], who tried to re-open the direct communications between Central Asia and ]. By 750, the Tibetans had lost almost all of their central Asian possessions to the ]. However, after Gao Xianzhi's defeat by the ] and ] at the ] (751) and the subsequent ] known as the ] (755), Chinese influence decreased rapidly and Tibetan influence resumed. | |||

| However general, the history of Tibet begins with the rule of ] (604–649 AD) who united parts of the ] Valley and ruled Tibet as a kingdom. In 640 he married ], the niece of the powerful Chinese emperor ]. | |||

| At its height in the 780s to 790s, the Tibetan Empire reached its highest glory when it ruled and controlled a territory stretching from modern-day Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Burma, China, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan. | |||

| Tibetan forces conquered the ] of modern ] and ] to the northeast between 663 and 672 AD. Tibet also dominated the ] and adjoining regions (now called ]), including the city of ], from 670 to 692 AD, when they were defeated by Chinese forces, and then again from 766 to the 800s. | |||

| In 821/822{{nbsp}}CE, Tibet and China signed a peace treaty. A bilingual account of this treaty, including details of the borders between the two countries, is inscribed on a ] which stands outside the ] temple in Lhasa.<ref>''A Corpus of Early Tibetan Inscriptions''. H. E. Richardson. Royal Asiatic Society (1985), pp. 106–43. {{ISBN|0-947593-00-4}}.</ref> Tibet continued as a Central Asian empire until the mid-9th century, when a civil war over succession led to the collapse of imperial Tibet. The period that followed is known traditionally as the '']'', when political control over Tibet became divided between regional warlords and tribes with no dominant centralized authority. An ] from Bengal took place in 1206. | |||

| The Tibetans were allied with the ] and eastern ]. In 747, Tibet's hold over Central Asia was weakened by the campaign of general ], who re-opened the direct communications between ] and ]. By 750 the Tibetans had lost almost all of their central Asian possessions to the ]. However, after Gao Xianzhi's defeat by the ] and ] at the ] river (751), Chinese influence decreased rapidly and Tibetan influence resumed. Tibet conquered large sections of northern India and even briefly took control of the Chinese capital ] in 763 during the chaos of the ].<ref>Beckwith, Christopher I. ''The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia'', p. 146. (1987) Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02469-3.</ref> | |||

| === Yuan dynasty === | |||

| There was a stone pillar, the Lhasa Shöl ''rdo-rings'', in the ancient village of ] in front of the ] in Lhasa, dating to c. 764 AD during the reign of ]. It also contains an account of the brief capture of ], the Chinese capital, in 763 AD, during the reign of ].<ref>''A Corpus of Early Tibetan Inscriptions''. H. E. Richardson. Royal Asiatic Society (1985), pp. 1–25. ISBN 0-94759300/4.</ref><ref>]. R. A. Stein. 1962. 1st English edition 1972. Stanford University Press, p. 65. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 (pbk).</ref> | |||

| {{main|Mongol conquest of Tibet|Tibet under Yuan rule}} | |||

| ], c. 1294]] | |||

| The Mongol ], through the ], or Xuanzheng Yuan, ruled Tibet through a top-level administrative department. One of the department's purposes was to select a '']'' ("great administrator"), usually appointed by the lama and confirmed by the Mongol emperor in Beijing.<ref name="China's Tibet Policy">Dawa Norbu. '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230414142810/https://books.google.com/books?id=kD8gTL6IIDYC&dq=Xuanzheng+Yuan&pg=PA139 |date=April 14, 2023 }}'', p. 139. Psychology Press.</ref> The ] lama retained a degree of autonomy, acting as the political authority of the region, while the ''dpon-chen'' held administrative and military power. Mongol rule of Tibet remained separate from the main provinces of China, but the region existed ]. If the Sakya lama ever came into conflict with the ''dpon-chen'', the ''dpon-chen'' had the authority to send Chinese troops into the region.<ref name="China's Tibet Policy"/> | |||

| Tibet retained nominal power over religious and regional political affairs, while the Mongols managed a structural and administrative<ref>Wylie. p.104: 'To counterbalance the political power of the lama, Khubilai appointed civil administrators at the Sa-skya to supervise the mongol regency.'</ref> rule over the region, reinforced by the rare military intervention. This existed as a "] structure" under the Yuan emperor, with power primarily in favor of the Mongols.<ref name="China's Tibet Policy"/> Mongolian prince ] gained temporal power in Tibet in the 1240s and sponsored ], whose seat became the capital of Tibet. ], Sakya Pandita's nephew became ] of ], founder of the Yuan dynasty. | |||

| In 821/822 AD Tibet and China signed a peace treaty. A bilingual account of this treaty including details of the borders between the two countries are inscribed on a stone pillar which stands outside the ] temple in Lhasa.<ref>'A Corpus of Early Tibetan Inscriptions''. H. E. Richardson. Royal Asiatic Society (1985), pp. 106–43. ISBN 0-94759300/4.</ref> Tibet continued as a Central Asian empire until the mid-9th century. | |||

| Yuan control over the region ended with the Ming overthrow of the Yuan and ]'s revolt against the Mongols.<ref name="Rossabi194">Rossabi 1983, p. 194</ref> Following the uprising, Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen founded the ], and sought to reduce Yuan influences over Tibetan culture and politics.<ref>Norbu, Dawa (2001) p. 57</ref> | |||

| ===The Mongols and Yuan Dynasty=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| At the end of the 1230s, the ] turned their attention to Tibet. At that time, Mongol armies had already conquered Northern China, much of Central Asia, and were operating in Russia and what is now Ukraine. The Tibetan nobility, however, was fragmented and mainly occupied with internal strife. ], a brother of ], entered the country with military force in 1240. A second invasion led to the submission of almost all Tibetan states. In 1244, Göden ordered the ] to meet him in ], and in 1247 Sakya became the Mongolian representative in Tibet. Sakya was accompagnied by two of his nephews: ] (''Phyag-na Rdo-rje'') would later marry a daughter of ], and ] would become Kublai's spiritual teacher. Although there was another Mongol expedition into Tibet in 1251/52, generally spoken the Tibetan experience with the Mongols was much less traumatic than that of other peoples. | |||

| === Phagmodrupa, Rinpungpa and Tsangpa dynasties === | |||

| On the other hand, Tibetan lamas would gain considerable influence in different Mongol clans, not only with Kublai, but for example also with the ]ids. Kublai's success in succeeding ] as Great Khan meant that after 1260, Phagpa and the House of Sakya would only wield greater influence. Phagpa became head of all buddhists monks in the ] empire, and Sakya would become the administrative center of Tibet. The lamaist clergy would receive considerable financial support, at the cost of mainly the Chinese areas ruled by the Yuan Dynasty. Tibet would also enjoy a rather high degree of autonomy compared to other parts of the Yuan empire, though further expeditions took place in 1267, 1277, 1281 and 1290/91.<ref>Dieter Schuh, ''Tibet unter der Mongolenherrschaft'', in: Michael Weiers (editor), ''Die Mongolen. Beiträge zu ihrer Geschichte und Kultur'', Darmstadt 1986, p. 283-289</ref> | |||

| {{main|Phagmodrupa dynasty|Rinpungpa|Tsangpa}} | |||

| {{further|Sino-Tibetan relations during the Ming dynasty}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Between 1346 and 1354, Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen toppled the Sakya and founded the Phagmodrupa dynasty. The following 80 years saw the founding of the ] school (also known as Yellow Hats) by the disciples of ], and the founding of the important ], ] and ] monasteries near Lhasa. However, internal strife within the dynasty and the strong localism of the various fiefs and political-religious factions led to a long series of internal conflicts. The minister family ], based in ] (West Central Tibet), dominated politics after 1435. In 1565 they were overthrown by the ] dynasty of ] which expanded its power in different directions of Tibet in the following decades and favoured the ] sect. | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| ===Late 14th - 16th Century=== | |||

| | align = right | |||

| Between 1346 and 1354, already towards the end of the Yuan dynasty, the House of ] would topple the Sakya. The following 80 years were a period of relative stability. They also saw the birth of the ] school (also known as ''Yellow Hats'') by the disciples of ], and the founding of the ], ], and ] monasteries near Lhasa. After the 1430s, the country entered another period of internal power struggles.<ref>Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz, ''Kleine Geschichte Tibets'', München 2006, p. 98-104</ref> | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 300 | |||

| | image1 = Khoshut Khanate.png | |||

| | caption1 = The ], 1642–1717 | |||

| | image2 = Carte la plus generale et qui comprend la Chine, la Tartarie Chinoise, et le Thibet (1734).jpg | |||

| | caption2 = Tibet in 1734. ''Royaume de Thibet'' ("Kingdom of Tibet") in ''la Chine, la Tartarie Chinoise, et le Thibet'' ("China, Chinese ], and Tibet") on a 1734 map by ], based on earlier Jesuit maps. | |||

| | image3 = Qing china.jpg | |||

| | caption3 = Tibet in 1892 during the ] | |||

| }} | |||

| === Rise of Ganden Phodrang and Buddhist Gelug school === | |||

| ===The Dalai Lama Lineage=== | |||

| {{Main|Ganden Phodrang}} | |||

| In 1578, ] of the ] Mongols decided to invite ], a high lama of the Gelugpa school. They met in ], and Altan Khan bestowed the title ''Dalai Lama''<ref>''Dalai'' is the Mongolian word for ''ocean'', a translation of the Tibetan title Gyatso.</ref> on Sönam Gyatso, and placed him in a reincarnation line with ] and ].<ref>Chinese authors sometimes like to point out that Altan Khan was a tributary of China, or even allude to him being a subordinate. This, however, not only ignores the often merely symbolic nature of the Chinese tributary system during Ming and Qing dynasty (see for example a very short discussion on p. 140f of J.K.Fairbank, S.Y.Tseng,''On the Ch'ing tributary system'', Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 6, No. 2. (Jun., 1941), pp. 135-246), but also the fact that by the end of the 1570s, the relations between the Ming and Altan Khan were once again marred by border raids (for this and the meeting between Altan Khan and Södnam Gyatso: Micheal Weiers, ''Geschichte der Mongolen'', Stuttgart 2004, p.175)</ref> While this did not really mark the beginning of a massive conversion of Mongols to Buddhism (this would only happen in the 1630s), it did lead to the widespread use of Buddhist ideology for the legitimation of power among the Mongol nobility. Lastly, the ] was a grandson of Altan Khan.<ref>Micheal Weiers, ''Geschichte der Mongolen'', Stuttgart 2004, p.175ff</ref> | |||

| In 1578, ] of the ] Mongols gave ], a high lama of the Gelugpa school, the name '']'', ''Dalai'' being the Mongolian translation of the Tibetan name ''Gyatso'' "Ocean".<ref>Laird 2006, pp. 142–143.</ref> | |||

| The ] (1617–1682) is known for unifying the Tibetan heartland under the control of the ] school of ], after defeating the rival ] and ] sects and the secular ruler, the ] prince, in a prolonged civil war. His efforts were successful in part because of aid from ], the ] leader of the ]. With Güshi Khan as a largely uninvolved overlord, the 5th Dalai Lama and his intimates established a civil administration which is referred to by historians as the ''Lhasa state''. This Tibetan regime or government is also referred to as the ]. | |||

| ===Khoshud, Dzungars, and the Qing Dynasty=== | |||

| In the 1630s, Tibet would become entangled in the power struggles between the rising ] and various Mongol and ] factions. ] of the ], on the retreat from the Manchu, set out to Tibet to destroy the Yellow Hat school. He died on the way in ] in 1634,<ref>Micheal Weiers, ''Geschichte der Mongolen'', Stuttgart 2004, p.182f</ref> but his vassal ] would continue the fight, even having his own son Arslan killed for changing sides. Tsogt Taij was defeated and killed by ] of the ] in 1637, who would in turn become the overlord over Tibet, and act as a "Protector of the Yellow Church".<ref>Rene Grousset, ''The Empire of the Steppes'', New Brunswick 1970, p. 522</ref> Güshi helped the ] to establish himself as the highest spiritual and political authority in Tibet and destroyed any potential rivals, like the prince of Tsang. The time of the fifth Dalai Lama was, however, also a period of rich cultural development. | |||

| === Qing dynasty === | |||

| His death was kept secret for 15 years by the regent ({{bo|t=desi|w=sde-srid|lang=yes}}), ]. His reasons for doing so are not really clear, but the ] was only enthroned in 1697. The new Dalai Lama did not really live up to expectations: he would blackmail the Panchen Lama to let him return to the lay class, and afterwards grow long hair and spend the nights outside the palace, with women of his choice. He gained fame for writing love poetry.<ref>Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz, ''Kleine Geschichte Tibets'', München 2006, p. 109-122</ref> | |||

| {{main|Chinese expedition to Tibet (1720)|Tibet under Qing rule}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In 1705, ] of the Khoshud used the 6th Dalai Lama's escapades as excuse to take control of Tibet. The regent was murdered, and the Dalai Lama sent to Beijing. He died on the way, in ], ostensibly from illness. Lobzang Khan appointed a new Dalai Lama, who however was not accepted by the Gelugpa school. A ] was found in Koko Nur. | |||

| ] rule in Tibet began with their ] when they expelled the invading ]. ] came under Qing control in 1724, and eastern ] was incorporated into neighbouring Chinese provinces in 1728.<ref name="Wang 162-6">Wang Jiawei, "]", 2000, pp. 162–6.</ref> Meanwhile, the Qing government sent resident commissioners called '']s'' to Lhasa. In 1750, the Ambans and the majority of the ] and ] living in Lhasa were killed in ], and Qing troops arrived quickly and suppressed the rebels in the next year. Like the preceding Yuan dynasty, the Manchus of the Qing dynasty exerted military and administrative control of the region, while granting it a degree of political autonomy. The Qing commander publicly executed a number of supporters of the rebels and, as in 1723 and 1728, made changes in the political structure and drew up a formal organization plan. The Qing now restored the Dalai Lama as ruler, leading the governing council called '']'',<ref>Kychanov, E.I. and Melnichenko, B.I. Istoriya Tibeta s drevneishikh vremen do nashikh dnei . Moscow: Russian Acad. Sci. Publ., p.89-92</ref> but elevated the role of ''Ambans'' to include more direct involvement in Tibetan internal affairs. At the same time, the Qing took steps to counterbalance the power of the aristocracy by adding officials recruited from the clergy to key posts.<ref>Goldstein 1997, pg. 18</ref> | |||

| For several decades, peace reigned in Tibet, but in 1792, the Qing ] sent ] to push the invading ]ese out. This prompted yet another Qing reorganization of the Tibetan government, this time through a written plan called the "Twenty-Nine Regulations for Better Government in Tibet". Qing military garrisons staffed with Qing troops were now also established near the Nepalese border.<ref>Goldstein 1997, pg. 19</ref> Tibet was dominated by the Manchus in various stages in the 18th century, and the years immediately following the 1792 regulations were the peak of the Qing imperial commissioners' authority; but there was no attempt to make Tibet a Chinese province.<ref>Goldstein 1997, pg. 20</ref> | |||

| The ] invaded Tibet in 1717, deposed and killed a pretender to the position of Dalai Lama (who had been promoted by Lhabzang, the titular King of Tibet), which met with widespread approval. However, they soon began to loot the holy places of Lhasa which brought a swift response from Emperor ] in 1718, but his military expedition was annihilated by the Dzungars not far from Lhasa.<ref name = "Richardson-p48">Richardson, Hugh E. (1984). ''Tibet and its History''. Second Edition, Revised and Updated, pp. 48-9. Shambhala. Boston & London. ISBN 0-87773-376-7 (pbk)</ref><ref>Stein, R. A. ''Tibetan Civilization''. (1972), p. 85. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN 0-8047-0901-7.(paper)</ref> | |||

| In 1834, the ] invaded and annexed ], a culturally Tibetan region that was an independent kingdom at the time. Seven years later, a Sikh army led by ] invaded western Tibet from Ladakh, starting the ]. A Qing-Tibetan army repelled the invaders but was in turn defeated when it chased the Sikhs into Ladakh. The war ended with the signing of the ] between the Chinese and Sikh empires.<ref>The Sino-Indian Border Disputes, by Alfred P. Rubin, The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Jan. 1960), pp. 96–125.</ref> | |||

| Many ] and ]s were executed and Tibetans visiting Dzungar officials were forced to stick their tongues out so the Dzungars could tell if the person recited constant mantras (which was said to make the tongue black or brown). This allowed them to pick the Nyingmapa and Bonpos, who recited many magic-mantras.<ref>Norbu, Namkhai. (1980). "Bon and Bonpos". ''Tibetan Review'', December, 1980, p. 8.</ref> This habit of sticking one's tongue out as a mark of respect on greeting someone has remained a Tibetan custom until recent times. | |||

| ], a Buddhist temple complex in ], Hebei, built between 1767 and 1771. The temple was modeled after the ].]] | |||

| A second, larger, expedition sent by Emperor Kangxi expelled the ] from Tibet in 1720 and the troops were hailed as liberators. They brought Kelzang Gyatso with them from Kumbum to Lhasa and he was installed as the seventh Dalai Lama in ].<ref name = "Richardson-p48"/> | |||

| As the Qing dynasty weakened, its authority over Tibet also gradually declined, and by the mid-19th century, its influence was minuscule. Qing authority over Tibet had become more symbolic than real by the late 19th century,<ref>Goldstein 1989, pg. 44</ref><ref>Goldstein 1997, pg. 22</ref><ref>Brunnert, H. S. and Hagelstrom, V. V. _Present Day Political Organization of China_, Shanghai, 1912. p. 467.</ref><ref>{{cite web |author=Stas Bekman: stas (at) stason.org |url=http://stason.org/TULARC/travel/tibet/B6-What-was-Tibet-s-status-during-China-s-Qing-dynasty-164.html |title=What was Tibet's status during China's Qing dynasty (1644–1912)? |publisher=Stason.org |access-date=August 26, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080407223734/http://stason.org/TULARC/travel/tibet/B6-What-was-Tibet-s-status-during-China-s-Qing-dynasty-164.html |archive-date=April 7, 2008 |url-status=live}}</ref> although in the 1860s, the Tibetans still chose for reasons of their own to emphasize the empire's symbolic authority and make it seem substantial.<ref>The Cambridge History of China, vol. 10, p. 407.</ref> | |||

| The ] put ] under their rule in 1724, and incorporated eastern ] into neighbouring Chinese provinces in 1728.<ref name="Wang 162-6">Wang Jiawei, "The Historical Status of China's Tibet", 2000, pp. 162-6</ref> The Qing government sent a resident commissioner (]) to Lhasa. Tibetan factions rebelled in 1750 and killed the ambans. Then, a Qing army entered and defeated the rebels and installed an administration headed by the Dalai Lama. The number of soldiers in Tibet was kept at about 2,000. The defensive duties were partly helped out by a local force which was reorganized by the resident commissioner, and the Tibetan government continued to manage day-to-day affairs as before. | |||

| In 1774, a ] ], ], travelled to ] to investigate prospects of trade for the ]. His efforts, while largely unsuccessful, established permanent contact between Tibet and the ].<ref>Teltscher 2006, pg. 57</ref> However, in the 19th century, tensions between foreign powers and Tibet increased. The ] was expanding its ] into the ], while the ] and the ] were both doing likewise in ].{{citation needed|date=October 2022}} | |||

| While the ancient Sino-Tibetan relationships are complex, there can be no question regarding the subordination of Tibet to Manchu-ruled China following the chaotic era of the 6th and 7th Dalai Lamas in the first decades of the 18th century.<ref name=MCG>Goldstein, Melvyn C., "A History Of Modern Tibet", University of California Press, p44</ref> In 1751, the Manchu (Qing) ] established the Dalai Lama as both the spiritual leader and political leader of Tibet who lead a government (]) with four Kalöns in it.<ref name="Wang 170-3">Wang Jiawei, "The Historical Status of China's Tibet", 2000, pp. 170–3</ref> | |||

| In 1904, a ], spurred in part by a fear that ] was extending its power into Tibet as part of ], was launched. Although the expedition initially set out with the stated purpose of resolving border disputes between Tibet and ], it quickly turned into a military invasion. The British expeditionary force, consisting of ], quickly invaded and captured Lhasa, with the ] fleeing to the countryside.<ref name="smith154-6">Smith 1996, pp. 154–6</ref> Afterwards, the leader of the expedition, ], negotiated the ] with the Tibetans, which guaranteed the British great economic influence but ensured the region ]. The Qing imperial resident, known as the ], publicly repudiated the treaty, while the British government, eager for friendly relations with China, negotiated a new treaty two years later known as the ]. The British agreed not to annex or interfere in Tibet in return for an indemnity from the Chinese government, while China agreed not to permit any other foreign state to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet.<ref name="smith154-6"/> | |||

| In 1788, ] forces sent by ], the Regent of ], invaded Tibet, occupying a number of frontier districts. The young Panchen Lama fled to Lhasa and the ] ] sent troops to Lhasa, upon which the Nepalese withdrew agreeing to pay a large annual sum. | |||

| In 1910, the Qing government sent ] under ] to establish direct Manchu-Chinese rule and, in an imperial edict, deposed the Dalai Lama, who fled to British India. Zhao Erfeng defeated the Tibetan military conclusively and expelled the Dalai Lama's forces from the province. His actions were unpopular, and there was much animosity against him for his mistreatment of civilians and disregard for local culture.{{citation needed|date=October 2022}} | |||

| In 1791 the Nepalese Gurkhas invaded Tibet a second time, seizing ] and destroyed, plundered, and desecrated the great ] Monastery. The Panchen Lama was forced to flee to Lhasa once again. The Qianlong Emperor then sent an army of 17,000 men to Tibet. In 1793, with the assistance of Tibetan troops, they managed to drive the Nepalese troops to within about 30 km of ] before the Gurkhas conceded defeat and returned all the treasure they had plundered.<ref>Teltscher, Kate (2006). ''The High Road to China: George Bogle, the Panchen Lama, and the First British Expedition to Tibet'', pp. 244-246. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. ISBN 978-0-374-21700-6.</ref> Soon the Chinese emperor decreed that the selection of the Dalai Lama and other high lamas such as the Panchen Lama was under the supervision of Qing government's Amban Commissioners in Lhasa.<ref name=MCG/> | |||

| === |

=== Post-Qing period === | ||

| {{Main|Tibet (1912–1951)}} | |||

| {{main|British expedition to Tibet}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{wikisourcepar|Littell's Living Age/Volume 137/Issue 1775/Tibet|"Tibet" (1878) is an account of early British attempts to gain influence in Tibet.}}]]]]]]]]] | |||

| ], an ], early 20th century. Their hereditary occupation included disposal of corpses and leather work.]] | |||

| The first Europeans to arrive in Tibet were ] missionaries in 1624 by the hand of ], and were welcomed by the Tibetans who allowed them to build a ]. The 18th century brought more ] and ] from Europe who gradually met opposition from Tibetan ]s who finally expelled them from Tibet in 1745. However, at the time not all Europeans were banned from the county — in 1774 a Scottish nobleman, ], came to ] to investigate ] for the ], introducing the first ]es into Tibet.<ref>Teltscher, Kate. (2006). ''The High Road to China: George Bogle, the Panchen Lama and the First British Expedition to Tibet'', p. 57. Bloomsbury, London, 2006. ISBN 0374217009; ISBN 978-0-7475-8484-1; | |||

| After the ] (1911–1912) toppled the Qing dynasty and the last Qing troops were escorted out of Tibet, the new ] apologized for the actions of the Qing and offered to restore the Dalai Lama's title.<ref>Mayhew, Bradley and Michael Kohn. (2005). ''Tibet'', p. 32. Lonely Planet Publications. {{ISBN|1-74059-523-8}}.</ref> The Dalai Lama refused any Chinese title and declared himself ruler of an ].<ref name="shakya5">Shakya 1999, pg. 5</ref> In 1913, Tibet and ] concluded ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://ww38.ltwa.net/library/index.php?option=com_multicategories&view=article&id=170&catid=30:news&Itemid=12|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121030061528/http://www.ltwa.net/library/index.php?option=com_multicategories&view=article&id=170&catid=30%3Anews&Itemid=12 |url-status=dead |title=ltwa.net|archive-date=October 30, 2012 |website=ww38.ltwa.net}}</ref> The ROC continued to view the former Qing territory as its own, including Tibet.<ref name=":Laikwan2">{{Cite book |last=Laikwan |first=Pang |title=One and All: The Logic of Chinese Sovereignty |date=2024 |publisher=] |isbn=9781503638815 |location=Stanford, CA |doi=10.1515/9781503638822}}</ref>{{Rp|page=69}} For the next 36 years, the 13th Dalai Lama and the ] governed Tibet. During this time, Tibet fought Chinese warlords for control of the ethnically Tibetan areas in ] and ] (parts of Kham and Amdo) along the upper reaches of the ].<ref name="Wang 150">Wang Jiawei, "The Historical Status of China's Tibet", 2000, p. 150.</ref> In 1914, the Tibetan government signed the ] with Britain, which recognized Chinese suzerainty over Tibet in return for a border settlement. China refused to sign the convention.<ref>{{citation |last1=Fisher |first1=Margaret W. |last2=Rose |first2=Leo E. |last3=Huttenback |first3=Robert A. |title=Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh |date=1963 |publisher=Praeger |url=https://archive.org/details/himalayanbattleg0000unse/mode/2up |via=archive.org |pages=77–78 |quote=By refusing to sign it, however, the Chinese lost an opportunity to become the acknowledged suzerain of Tibet. The Tibetans were therefore free to make their own agreement with the British.}}</ref> Tibet continued to lack clear boundaries or international recognition of its status.<ref name=":Laikwan2" />{{Rp|page=69}} | |||

| Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. ISBN 978-0-374-21700-6</ref> | |||

| When in the 1930s and 1940s the regents displayed negligence in affairs, the Kuomintang Government of the Republic of China took advantage of this to expand its reach into the territory.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WIJFuD-cH_IC&q=dalai+lama+kuomintang+brief+civil+war |title=The Search for the Panchen Lama |author=Isabel Hilton |year=2001 |publisher=W. W. Norton & Company |page=112 |isbn=978-0-393-32167-8 |access-date=June 28, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160610000748/https://books.google.com/books?id=WIJFuD-cH_IC&dq=ma+bufang+taiwan&q=dalai+lama+kuomintang+brief+civil+war#v=snippet&q=dalai%20lama%20kuomintang%20brief%20civil%20war&f=false |archive-date=June 10, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> On December 20, 1941, Kuomintang leader ] noted in his diary that Tibet would be among the territories which he would demand as restitution for China following the conclusion of World War II.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mitter |first=Rana |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1141442704 |title=China's good war : how World War II is shaping a new nationalism |date=2020 |publisher=The Belknap Press of ] |isbn=978-0-674-98426-4 |location=Cambridge, Massachusetts |pages=45 |oclc=1141442704 |access-date=October 15, 2022 |archive-date=April 2, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230402121743/https://www.worldcat.org/title/1141442704 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| However by the 19th century the situation of foreigners in Tibet grew more ominous. The ] was encroaching from northern ] into the ] and ] and the ] of the ]s was expanding south into ] and each power became suspicious of intent in Tibet. By the 1850s Tibet had banned all foreigners from Tibet and shut its borders to all outsiders. In 1840, ] arrived in Tibet, hoping that he would be able to trace the origin of the ] ethnic group. | |||

| === From 1950 to present === | |||

| In 1865 ] began secretly mapping Tibet. Trained Indian surveyor-spies disguised as ]s or traders counted their strides on their travels across Tibet and took readings at night. ], the most famous, measured the ] and ] and ] of ] and traced the ]. | |||

| {{Main|History of Tibet (1950–present)}} | |||

| ], 2010.]] | |||

| Emerging with control over most of ] after the ], the ] ] in 1950 and negotiated the ] with the newly enthroned ]'s government, affirming the People's Republic of China's sovereignty but granting the area autonomy. Subsequently, on his journey into exile, the 14th Dalai Lama completely repudiated the agreement, which he has repeated on many occasions.<ref> Archived on September 28, 2011.</ref><ref>], '']'' Harper San Francisco, 1991</ref> According to the ], the Chinese used the Dalai Lama to gain control of the military's training and actions.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP82-00457R009600210006-1.pdf |title=1.Chinese Communist Troops in Tibet, 2. Chinese Communist Program for Tibet |access-date=February 10, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170123133521/https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP82-00457R009600210006-1.pdf |archive-date=January 23, 2017 |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| The Dalai Lama had a strong following as many people from Tibet looked at him not just as their political leader, but as their spiritual leader.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP82R00025R000100060024-3.pdf |title=Notes for DCI briefing of Senate Foreign Relations Committee on 28 April 1959 |access-date=February 10, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170123081300/https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP82R00025R000100060024-3.pdf |archive-date=January 23, 2017 |url-status=dead}}</ref> After the Dalai Lama's government fled to ], India, during the ], it established a ]. Afterwards, the ] in Beijing renounced the agreement and began implementation of the halted social and political reforms.<ref>{{Cite book |title=Governing China's Multiethnic Frontiers |page=197 |first=Morris |last=Rossabi |chapter=An Overview of Sino-Tibetan Relations |publisher=] |year=2005}}</ref> During the ], over 200,000 Tibetans may have died<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.refworld.org/docid/49749d3dc.html |title=World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – China : Tibetans |publisher=Minority Rights Group International |date=July 2008 |access-date=April 23, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141101012043/http://www.refworld.org/docid/49749d3dc.html |archive-date=November 1, 2014 |url-status=live}}</ref> and approximately 6,000 monasteries were destroyed during the ]—destroying the vast majority of historic Tibetan architecture.<ref name="Kevin">{{Cite book |title=Freedom of religion and belief: a world report |first1=Kevin |last1=Boyle |first2=Juliet |last2=Sheen |publisher=Routledge |year=2003 |isbn=978-0-415-15977-7}}</ref> | |||

| ====British Invasion==== | |||

| In 1980, General Secretary and reformist ] visited Tibet and ushered in a period of social, political, and ].<ref name="Bank"/> At the end of the decade, however, before the ], monks in the ] and ] monasteries started protesting for independence. The government halted reforms and started an anti-] campaign.<ref name="Bank">{{cite magazine |title=As Tibet Goes... |first1=David |last1=Bank |first2=Peter |last2=Leyden |magazine=] |date=January 1990 |volume=15 |issue=1 |issn=0362-8841}}</ref> Human rights organisations have been critical of the Beijing and Lhasa governments' approach to ] when cracking down on separatist convulsions that have occurred around monasteries and cities, most recently in the ]. | |||

| At the beginning of the twentieth century both the British Empire and Russian Empire competed for supremacy in Central Asia. Tibet was the biggest prize of this rivalry. To forestall the Russians, in 1904, a British expedition led by Colonel Francis Younghusband was sent to Lhasa to force a trading agreement and to prevent Tibetans from establishing a relationship with the Russians. | |||

| The central region of Tibet is now an ] within China, the ]. The Tibet Autonomous Region is a province-level entity of the People's Republic of China. It is governed by a People's Government, led by a chairman. In practice, however, the chairman is subordinate to the branch secretary of the ] (CCP). In 2010 it was reported that, as a matter of convention, the chairman had almost always been an ethnic Tibetan, while the party secretary had always been ethnically non-Tibetan.<ref>{{Cite news |date=January 15, 2010 |title=Leadership shake-up in China's Tibet: state media |publisher=] |agency=] |location=France |url=http://www.france24.com/en/20100115-leadership-shake-chinas-tibet-state-media |url-status=dead |access-date=July 29, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100118095132/http://www.france24.com/en/20100115-leadership-shake-chinas-tibet-state-media |archive-date=January 18, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| On July 19, 1903, Younghusband arrived at Gangtok, the capital city of the Indian state of Sikkim, to prepare for his mission. A letter from the under-secretary to the government of India to Younghusband on July 26, 1903 stated that “In the event of your meeting the Dalai Lama, the government of India authorizes you to give him the assurance which you suggest in your letter.” | |||

| <ref name = "Younghusband-p2"> The British Invasion of Tibet: Colonel Younghusband, page 2</ref> The British took a few months to prepare for the expedition which pressed into Tibetan territories in early December 1903. The entire British force numbered over 3,000 fighting men and was accompanied by 7,000 sherpas, porters and camp followers. | |||

| == Geography == | |||

| The Tibetans were aware of the expedition. To avoid bloodshed the Tibetan general at Yetung pledged that if the Tibetans make no attack upon the British, no attack should be made by the British on them. Colonel Younghusband on December 6, 1903 replied that “we are not at war with Tibet and that, unless we are ourselves attacked, we shall not attack the Tibetans.” <ref> The British Invasion of Tibet: Colonel Younghusband, page 189</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Geography of Tibet}} | |||

| ] and surrounding areas above 1600 m – ].<ref name="GLOBE" /><ref name="ETOPO1" /> Tibet is often called the "roof of the world".]] | |||

| ] | |||

| All of modern China, including Tibet, is considered a part of ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://science.nationalgeographic.com/science/earth/surface-of-the-earth/plateaus-article.html |title=plateaus|access-date=May 16, 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090401160422/http://science.nationalgeographic.com/science/earth/surface-of-the-earth/plateaus-article.html|archive-date=April 1, 2009|url-status=dead}}</ref> Historically, some European sources also considered parts of Tibet to lie in ]. Tibet is west of the ]. In China, Tibet is regarded as part of {{lang|zh|西部}} ({{transliteration|zh|Xībù}}), a term usually translated by Chinese media as "the Western section", meaning "Western China". | |||

| === Mountains and rivers === | |||

| Despite the mutual agreement, the British expedition did take the lives of a few thousand unprepared Tibetan soldiers and civilians. The biggest massacre took place on March 31, 1904 at a mountain pass halfway to Gyantse near a village called Guru. Colonel Younghusband tricked the 2,000 Tibetan soldiers guarding the pass into extinguishing the burning ropes of their basic rifles before firing at them with the Maxim machine guns and rifles. The Tibetan casualty, according to Younghusband’s account, was “500 killed and wounded.” <ref> The British Invasion of Tibet: Colonel Younghusband, page 235</ref> Others have claimed that the Tibetan casualty was as high as 1,300. | |||

| ] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Tibet has some of the world's tallest mountains, with several of them making the top ten list. ], located on the border with ], is, at {{convert|8848.86|m|ft|0}}, the ] on earth. Several major rivers have their source in the ] (mostly in present-day Qinghai Province). These include the ], ], ], ], ], ] and the ] (]).<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.circleofblue.org/waternews/world/china-tibet-and-the-strategic-power-of-water/ |title=Circle of Blue, 8 May 2008 China, Tibet, and the strategic power of water |publisher=Circleofblue.org |date=May 8, 2008 |access-date=March 26, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080702122515/http://www.circleofblue.org/waternews/world/china-tibet-and-the-strategic-power-of-water/ |archive-date=July 2, 2008 |url-status=dead}}</ref> The ], along the ], is among the deepest and longest canyons in the world. | |||

| Tibet has been called the "Water Tower" of Asia, and China is investing heavily in water projects in Tibet.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.futurewater.nl/uk/projects/tibet/ |title=The Water Tower Function of the Tibetan Autonomous Region. |publisher=Futurewater.nl |access-date=August 26, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120425233325/http://www.futurewater.nl/uk/projects/tibet/ |archive-date=April 25, 2012 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://english.people.com.cn/90780/91344/7571032.html |title=China to spend record amount on Tibetan water projects. |publisher=English.people.com.cn |date=August 16, 2011 |access-date=August 26, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111227231909/http://english.people.com.cn/90780/91344/7571032.html |archive-date=December 27, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| According to the British, their intention was to disarm Tibetan soldiers who were being surrounded. The slaughter was triggered by the Tibetans who fired the first shot. <ref> The British Invasion of Tibet: Colonel Younghusband, page 234</ref> But the accounts of those who pulled the triggers make it clear that the British had the intention of killing as many as possible. “From three sides at once a withering volley of magazine fire crashed into the crowded mass of Tibetans,” wrote Perceval Landon. “Under the appalling punishment of lead, they staggered, failed and ran…Men dropped at every yard.” <ref name = "VirtualTibet"> Virtual Tibet: Searching for Shangri-La from the Himalayas to Hollywood, page 195</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The British soldiers mowed down the Tibetans with machine guns as they fled. “I got so sick of the slaughter that I ceased fire, though the general’s order was to make as big a bag as possible,” wrote Lieutenant Arthur Hadow, commander of the Maxim guns detachment. “I hope I shall never again have to shoot down men walking away.” <ref name = "VirtualTibet"/> | |||

| The Indus and Brahmaputra rivers originate from the vicinities of Lake ] in Western Tibet, near ]. The mountain is a holy pilgrimage site for both ]s and Tibetans. The Hindus consider the mountain to be the abode of ]. The Tibetan name for Mount Kailash is Khang Rinpoche. Tibet has numerous high-altitude lakes referred to in Tibetan as ''tso'' or ''co''. These include ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. The Qinghai Lake (Koko Nor) is the largest lake in the People's Republic of China. | |||

| === Climate === | |||

| In a telegraph to his superior in India, the day after the massacre, Younghusband stated: “I trust the tremendous punishment they have received will prevent further fighting, and induce them to at last to negotiate.” <ref> The British Invasion of Tibet: Colonel Younghusband, page 237</ref> | |||

| The climate is severely dry nine months of the year, and average annual snowfall is only {{convert|46|cm|inch|abbr=in}}, due to the ]. Western passes receive small amounts of fresh snow each year but remain traversible all year round. Low temperatures are prevalent throughout these western regions, where bleak desolation is unrelieved by any vegetation bigger than a low bush, and where the wind sweeps unchecked across vast expanses of arid plain. The Indian ] exerts some influence on eastern Tibet. Northern Tibet is subject to high temperatures in the summer and intense cold in the winter. | |||

| {{Weather box | |||

| ], ], Tibet (2006)]] | |||

| |location = Lhasa (1986−2015 normals, extremes 1951−2022) | |||

| |metric first = Y | |||

| |single line = Y | |||

| |Jan high C = 8.4 | |||

| |Feb high C = 10.1 | |||

| |Mar high C = 13.3 | |||

| |Apr high C = 16.3 | |||

| |May high C = 20.5 | |||

| |Jun high C = 24.0 | |||

| |Jul high C = 23.3 | |||

| |Aug high C = 22.0 | |||

| |Sep high C = 20.7 | |||

| |Oct high C = 17.5 | |||

| |Nov high C = 12.9 | |||

| |Dec high C = 9.3 | |||

| | Jan mean C = −0.3 | |||