| Revision as of 14:37, 16 October 2008 view sourceJFD (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,235 edits →Content← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:11, 9 January 2025 view source 00yunje (talk | contribs)42 edits →Early tea drinking: added page number and link to betel nut chewing | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Brewed drink made from tea leaves}} | |||

| ] ].]] | |||

| {{About|the beverage made from Camellia sinensis|other uses}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2022}} | |||

| [[Image:Teaproducingcountries.svg|right|thumb|220px|Tea-producing countries.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.246.dk/teanations.html|title=Tea Producing Nations | |||

| {{Use British English|date=January 2014}} | |||

| |date=]|accessdate=2007-05-09}}</ref>]] | |||

| {{Infobox beverage | |||

| ]''.]] | |||

| | name = Tea | |||

| ] | |||

| | original_name = 茶 | |||

| '''Tea''' is the beverage made by ] parts of the '']'' plant in water,<ref>Webster's Third New International Dictionary</ref> and the colloquial name for the ''Camellia sinensis'' plant itself. | |||

| | type = Hot or cold beverage | |||

| | image = Longjing tea steeping in gaiwan.jpg | |||

| | caption = ] ] being infused in a '']'' | |||

| | origin = China<ref>{{cite news |first=Thomas |last=Fuller |title=A Tea From the Jungle Enriches a Placid Village |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/21/world/asia/21tea.html |work=] |location=New York |page=A8 |date=21 April 2008 |access-date=23 February 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170214133259/http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/21/world/asia/21tea.html |archive-date=14 February 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | introduced = First recorded in China in 59 BC, possibly originated earlier{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|pp=29–30}} | |||

| | color = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Tea''' is an aromatic ] prepared by pouring hot or ] over ] or fresh leaves of '']'', an ] ] native to ] which probably originated in the borderlands of ] and ].<ref name=Yamamoto /><ref>{{cite book|author1=Mary Lou Heiss|author2=Robert J. Heiss|title=The Story of Tea: A Cultural History and Drinking Guide|url=https://archive.org/details/storyofteacultur0000heis|quote=Camellia sinensis originated in southeast Asia, specifically around the intersection of 29th parallel and 98th meridian, the point of confluence of the lands of southwest China and Tibet|url-access=registration}}, north Burma, and northeast India, citing Mondal (2007) p. 519</ref>{{sfn|Heiss|Heiss|2007|pp=6–7}} Tea is also made, but rarely, from the leaves of '']''.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://sevencups.com/shop/lao-shu-dian-hong-old-tree-yunnan|title=Laoshu Dianhong (Old Tree Yunnan)}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://teatrekker.com/product/yunnan-da-bai-silver-needles/|title=Yunnan da Bai Silver Needles – Tea Trekker}}</ref><ref>Liu ''et al.'' (2012)</ref> After plain water, tea is the most widely consumed drink in the world.<ref name="Macfarlane">{{cite book |first1=Alan |last1=Macfarlane |author-link=Alan Macfarlane |last2=Macfarlane |first2=Iris |author-link2=Iris Macfarlane |title=The Empire of Tea |publisher=The Overlook Press |isbn=978-1-58567-493-0 |page= |year=2004 |url=https://archive.org/details/empireoftearemar00macf/page/32}}</ref> There are many different types of tea; some have a cooling, slightly bitter, and ] flavour,<ref name="ody">{{cite book |author1=Penelope Ody |title=Complete Guide to Medicinal Herbs |publisher=Dorling Kindersley Publishing |location=New York |year= 2000|page=48 |isbn=978-0-7894-6785-0 }}</ref> while others have profiles that include sweet, nutty, floral, or grassy ]. Tea has a ] effect in humans, primarily due to its ] content.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Cappelletti |first=Simone |last2=Piacentino |first2=Daria |last3=Sani |first3=Gabriele |last4=Aromatario |first4=Mariarosaria |title=Caffeine: cognitive and physical performance enhancer or psychoactive drug? |journal=Current Neuropharmacology |volume=13 |issue=1 |pages=71–88 |date=January 2015 |pmid=26074744 |pmc=4462044 |doi=10.2174/1570159X13666141210215655 |issn=1570-159X}}</ref> | |||

| Tea is the most widely-consumed beverage after water.<ref name="Macfarlane">{{cite book|author=Alan Macfarlane|coauthors=Iris Macfarlane|title=The Empire of Tea|publisher=The Overlook Press|isbn=1-58567-493-1|pages=32}}</ref> It has a cooling, slightly bitter, ] flavor.<ref name="ody"/> | |||

| An early credible record of tea drinking dates to the third century AD, in a medical text written by Chinese physician ].<ref>], p. 29: "beginning in the third century CE, references to tea seem more credible, in particular those dating to the time of Hua T'o, a highly respected physician and surgeon"</ref> It was popularised as a recreational drink during the Chinese ], and tea drinking subsequently spread to other East Asian countries. ] and merchants introduced it to Europe during the 16th century.<ref name="caff" /> During the 17th century, drinking tea became fashionable among the ], who started to plant tea on a large scale in ]. | |||

| The five types of tea most commonly found on the market are ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| The term ] refers to drinks not made from ''Camellia sinensis''. They are the infusions of fruit, leaves, or ], such as ] of ], ], or ]. These may be called ''tisanes'' or ''herbal infusions'' to prevent confusion with tea made from the tea plant. | |||

| The term "]" usually refers to an ] or ] of fruit or herbs that contains no ''Camellia sinensis''.<ref> URL accessed February 15, 2007.</ref> | |||

| == |

== Etymology == | ||

| '']'' is an ] plant that grows mainly in ] and ] climates. However, some varieties can also tolerate ] and are cultivated as far north as ] on the UK mainland<ref name="autogenerated1">Telegraph Online, 17 Sept 2005. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/gardening/main.jhtml?xml=/gardening/2005/09/17/gtea17.xml</ref> and ] in the ]. | |||

| {{main|Etymology of tea}} | |||

| In addition to ] or warmer, it requires at least 50 inches of rainfall a year, and prefers ].<ref>{{cite book |title=Camellias: A Practical Gardening Guide |last=Rolfe |first=Jim |coauthors=Yvonne Cave |year=2003 |publisher=Timber Press |isbn=0881925772 }}</ref> Many high quality tea plants grow at elevations up to 1500 meters (5,000 ft), as the plants grow more slowly and acquire a better flavor.<ref>{{cite book |title=Tea Cuisine: A New Approach to Flavoring Contemporary and Traditional Dishes |last=Pruess |first=Joanna |year=2006 |publisher=Globe Pequot |isbn=1592287417 }}</ref> | |||

| The ] of the various words for ''tea'' reflects the history of transmission of tea drinking culture and trade from China to countries around the world.{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|pp= 262–264}} Nearly all of the words for tea worldwide fall into three broad groups: ''te'', ''cha'' and ''chai'', present in English as ''tea'', ''cha'' or ''char'', and ''chai''. The earliest of the three to enter English is ''cha'', which came in the 1590s via the Portuguese, who traded in ] and picked up the ] pronunciation of the word.<ref name=oed>{{cite web|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=tea&allowed_in_frame=0|title=tea|publisher=]}}</ref>{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|p= 262}} The more common ''tea'' form arrived in the 17th century via the Dutch, who acquired it either indirectly from the Malay ''teh'', or directly from the ''tê'' pronunciation in ].<ref name=oed /> The third form ''chai'' (meaning "spiced tea") originated from a northern Chinese pronunciation of ''cha'', which travelled overland to Central Asia and ] where it picked up a Persian ending ''yi''. The Chinese word for tea itself was likely ultimately derived from the non-Sinitic languages of the botanical homeland of the tea plant in southwest China (or ]), possibly from an archaic ] root word *''la'', meaning "leaf".{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|p= 266}} | |||

| Only the top 1-2 inches of the mature plant are picked. These buds and leaves are called ''flushes'',<ref>{{cite book |author=Elizabeth S. Hayes |title=Spices and Herbs: Lore and Cookery |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=htsIVCwRsEcC&dq= |publisher=Courier Dover Publications |year=1980 |isbn=0486240266|accessdate=2008-09-20 |pages=74}}</ref> and a plant will grow a new flush every seven to ten days during the growing season. | |||

| Tea plants will grow into a tree if left undisturbed, but cultivated plants are pruned to waist height for ease of plucking.<ref name="Tea Cultivation"> URL accessed June, 2007.</ref> | |||

| Two principal varieties are used, the small-leaved China plant (''C. sinensis sinensis'') and the large-leaved Assam plant (''C. sinensis assamica''). Leaf size is the chief criterion for the classification of tea plants.<ref name=Mondal519>{{Harvnb|Mondal|2007|p=519}}</ref> Based upon this criterion, tea is classified into (1) Assam type characterized by the largest leaves, (2) China type characterized by the smallest leaves and (3) Cambod characterized by leaves of intermediate size.<ref name=Mondal519/> | |||

| == Processing and classification == | |||

| {{main|Tea processing}} | |||

| Types of tea are distinguished by the processing they undergo. Leaves of ''Camellia sinensis'' soon begin to wilt and ] if not dried quickly after picking. The leaves turn progressively darker because ] breaks down and ]s are released. This process, ''enzymatic oxidation'', is called ''fermentation'' in the tea industry although it is not a true fermentation: it is not caused by micro-organisms, and is not an anaerobic process. The next step in processing is to stop the ] process at a predetermined stage by heating, which deactivates the ]s responsible. With black tea this is done simultaneously with drying. | |||

| Without careful moisture and temperature control during its manufacture and thereafter, ] will grow on tea. This form of fungus causes real fermentation that will contaminate the tea with toxic and sometimes ]ic substances and off-flavors, rendering the tea unfit for consumption. | |||

| ] | |||

| Tea is traditionally classified based on producing technique:<ref name=LiuTong>{{cite book |author=Liu Tong |title=Chinese tea |publisher= China Intercontinental Press|location=Beijing|year=2005|pages=137 |isbn=7-5085-0835-1|oclc= |doi=}}</ref> | |||

| *]: Unwilted and unoxidized | |||

| *]: Unwilted and unoxidized but allowed to yellow | |||

| *]: Wilted and unoxidized | |||

| *]: Wilted, bruised, and partially oxidized | |||

| *]: Wilted, crushed, and fully oxidized | |||

| *]: Green Tea that has been allowed to ferment/compost | |||

| == Blending and additives == | |||

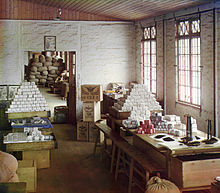

| ], before 1915]] | |||

| {{main|Tea blending and additives}} | |||

| Almost all teas in bags and most other teas sold in ] are blends. Blending may occur in the tea-planting area (as in the case of ]), or teas from many areas may be blended. The aim is to obtain better taste, better price or both, as more expensive, better-tasting tea may cover the inferior taste of cheaper varieties. Blending may also achieve a more consistent taste for the blend, regardless of the variation of taste among pure teas. | |||

| Various teas, as sold, are not pure varieties but have been enhanced through additives or special processing. Tea is indeed highly receptive to inclusion of various aromas; this may cause problems in processing, transportation and storage, but also allows for the design of an almost endless range of scented variants, such as ]-flavored, ]-flavored and many others. | |||

| == Content == | |||

| Tea contains ], a type of ]. In a fresh tea leaf, catechins can be up to 30% of the dry weight. Catechins are highest in concentration in white and green teas, while black tea has substantially fewer due to its oxidative preparation. Tea contains ], and the stimulant ] at about 3% of its dry weight, translating to between 30 mg and 90 mg per 8 oz (250 ml) cup depending on type, brand<ref>{{cite book |author=Bennett Alan Weinberg and Bonnie K. Bealer |title=The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=YdpL2YCGLVYC&dq= |publisher=Routledge |year=2001 |isbn=0415927226 |accessdate=2008-09-20 |pages=228}}</ref> and brewing method.<ref>M. B. Hicks, Y-H. P. Hsieh, L. N. Bell, ''Tea preparation and its influence on methylxanthine concentration'', Food Research International 29(3-4) 325-330 (1996)</ref> Tea also contains small amounts of ] and ].<ref>Graham H. N.; Green tea composition, consumption, and polyphenol chemistry; ''Preventive Medicine'' '''21'''(3):334-50 (1992)</ref> Tea also contains ], with certain types of ] made from old leaves and stems having the highest levels.<ref></ref> | |||

| Tea has almost no ]s, ], or ]. | |||

| == Origin and history == | == Origin and history == | ||

| According to {{Harvtxt|Mondal|2007|p=519}}: "Tea originated in ], specifically around the intersection of latitude 29°N and longitude 98°E, the point of confluence of the lands of northeast India, north Burma, southwest China and Tibet. The plant was introduced to more than 52 countries, from this ‘centre of origin’." | |||

| {{further|History of tea|History of tea in China}} | |||

| Based on morphological differences between the Assamese and Chinese varieties, botanists have long asserted a dual botanical origin for tea; however, statistical ], the same ] (2n=30), easy ]ization, and various types of intermediate hybrids and spontaneous ]s all appear to demonstrate a single place of origin for ''Camellia sinensis'' — the area including the northern part of ] and ] and ] provinces of China.<ref>{{Harvcolnb|Yamamoto|Kim|Juneja|1997|p=4}} "For a long time, botanists have asserted the dualism of tea origin from their observations that there exist distinct differences in the morphological characteristics between Assamese varieties and Chinese varieties. | |||

| ===Botanical origin=== | |||

| Hashimoto and Shimura reported that the differences in the morphological characteristics in tea plants are not necessarily the evidence of the dualism hypothesis from the researches using the statistical cluster analysis method. In recent investigations, it has also been made clear that both varieties have the same chromosome number (2n=30) and can be easily hybridized with each other. In addition, various types of intermediate hybrids or spontaneous polyploids of tea plants have been found in a wide area extending over the regions mentioned above. These facts may prove that the place of origin of ''Camellia sinensis'' is in the area including the northern part of the Burma, Yunnan, and Sichuan districts of China."</ref> | |||

| ]'', 1897]] | |||

| Yunnan Province has been identified as "the birthplace of tea...the first area where humans figured out that eating tea leaves or brewing a cup could be pleasant".<ref>{{cite news | first = Thomas | last = Fuller | title = A Tea From the Jungle Enriches a Placid Village | url = http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/21/world/asia/21tea.html | work = The New York Times | publisher = The New York Times Company | location = New York | page = A8 | date = 2008-04-21 }}</ref> | |||

| Tea plants are native to East Asia and the probable center of origin of tea is near the source of the ] from where it spread out fan-wise into southeast China, Indo-China and ]. Thus, the natural home of the tea plant is considered to be within the comparatively small fan-shaped area between ], ] and ] along the ] frontier in the west, through ] as far as the ] in the east, and from this line generally south through the hills to Burma and ] to ]. The west–east axis indicated above is about 2,400 km long extending from longitude 95°-120°E. The north–south axis covers about 1,920 km, starting from the northern part of Burma, latitude 29°N passing through ], ], Thailand, ] and on to Annan, reaching latitude 11°N.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Saikia |first=Gautam Kumar |date=19 September 2021 |title=Origin And Distribution Of The Tea Plant |url=https://teaorb.com/en-us/blog/origin-of-tea |website=teaorb.com}}</ref> | |||

| === Creation myths === | |||

| In one popular ], ], the legendary ], inventor of ] and ], was drinking a bowl of boiling water, some time around 2737 BC. The wind blew and a few leaves from a nearby tree fell into his water and began to change its color. The ever inquisitive and curious monarch took a sip of the brew and was pleasantly surprised by its flavor and its restorative properties. A variant of the legend tells that the emperor tested the medical properties of various herbs on himself, some of them poisonous, and found tea to work as an antidote.<ref>Chow p. 19-20 (Czech edition); also Arcimovicova p. 9, Evans p. 2 and others</ref> Shennong is also mentioned in ]'s famous early work on the subject, '']''.<ref>Lu Ju p. 29-30 (Czech edition)</ref> | |||

| Chinese (small-leaf) type tea (''C. sinensis'' var. ''sinensis'') may have originated in southern China possibly with hybridization of unknown wild tea relatives. However, since there are no known wild populations of this tea, its origin is speculative.<ref name="Meegahakumbura 1"/><ref name="Meegahakumbura 2"/> | |||

| === Tea and the Tang Dynasty === | |||

| In ancient times, a rather gruesome legend dating back to the ] was widely spread. In the legend, the founder of the ] school of Buddhism based on meditation (known as "Chan"), after meditating in front of a wall for nine years, accidentally fell asleep. He woke up in such disgust at his weakness, he cut off his own eyelids and they fell to the ground and took root, growing into tea bushes.<ref>Chow p. 20-21</ref> Sometimes, another version of the story is told with ] in place of ''Bodhidharma''<ref>Evans p. 3</ref> In another variant of the first mentioned myth, ''Gautama Buddha'' discovered tea when some leaves had fallen into boiling water.<ref>Okakura</ref> | |||

| Given their genetic differences forming distinct ]s, Chinese Assam-type tea (''C. sinensis'' var. ''assamica'') may have two different parentages – one being found in southern ] (], ]) and the other in western Yunnan (], ]). Many types of Southern Yunnan Assam tea have been hybridized with the closely related species '']''. Unlike Southern Yunnan Assam tea, Western Yunnan Assam tea shares many genetic similarities with Indian Assam-type tea (also ''C. sinensis'' var. ''assamica''). Thus, Western Yunnan Assam tea and Indian Assam tea both may have originated from the same parent plant in the area where southwestern China, Indo-Burma, and Tibet meet. However, as the Indian Assam tea shares no ]s with Western Yunnan Assam tea, Indian Assam tea is likely to have originated from an independent domestication. Some Indian Assam tea appears to have hybridized with the species '']''.<ref name="Meegahakumbura 1">{{cite journal |last1=Meegahakumbura |first1=MK |last2=Wambulwa |first2=MC |last3=Thapa |first3=KK |display-authors=etal |year=2016 |title=Indications for three independent domestication events for the tea plant (''Camellia sinensis'' (L.) O. Kuntze) and new insights into the origin of tea germplasm in China and India revealed by nuclear microsatellites |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=11 |issue=5 |page=e0155369 |pmid=27218820 |pmc=4878758 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0155369 |bibcode=2016PLoSO..1155369M|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="Meegahakumbura 2">{{cite journal |vauthors=Meegahakumbura MK, Wambulwa MC, Li MM, Thapa KK, Sun YS, Möller M, Xu JC, Yang JB, Liu J, Liu BY, Li DZ, Gao LM |display-authors=3 |date=2018 |title=Domestication origin and breeding history of the tea plant (Camellia sinensis) in China and India based on nuclear microsatellites and cpDNA sequence data |journal=Frontiers in Plant Science |volume=8 |page=2270 |pmid=29422908 |pmc=5788969 |doi= 10.3389/fpls.2017.02270|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| Whether or not these legends have any basis in fact, tea has played a significant role in Asian culture for centuries as a staple beverage, a curative, and a ]. For these reasons, it is not surprising that its discovery is ascribed to religious or royal origins. | |||

| Assuming a generation of 12 years, Chinese small-leaf tea is estimated to have diverged from Assam tea around 22,000 years ago, while Chinese Assam tea and Indian Assam tea diverged 2,800 years ago. The divergence of Chinese small-leaf tea and Assam tea would correspond to the last ].<ref name="Meegahakumbura 1"/><ref name="Meegahakumbura 2"/> | |||

| === China === | |||

| ] painting by artist ] illustrating scholars greeting in a tea ceremony]] | |||

| {{main|History of tea in China}} | |||

| The Chinese have enjoyed tea for thousands of years. While historically the use of tea as a medicinal ] useful for staying awake is unclear, China is considered to have the earliest records of tea drinking<ref name="encarta">{{cite web|url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761563182/Tea.html|title=Tea|publisher='']''|accessdate=2008-07-23}}</ref><ref name="columbia">{{cite web|url=http://www.bartleby.com/65/te/tea.html|title=Tea|publisher=''The ]'' <small>Sixth Edition. 2001-07</small>|accessdate=2008-07-23}}</ref>, with recorded tea use since the 10th century BC.<ref name="encarta"/> The ] used tea as medicine. | |||

| ===Early tea drinking=== | |||

| ] (ca. 600-517 BC), the classical Chinese philosopher, described tea as "the froth of the liquid jade" and named it an indispensable ingredient to the ]. Legend has it, master Lao was saddened by society's moral decay and sensing the end of the dynasty was near, he journeyed westward to the unsettled territories never to be seen again. While passing along the nation's border, he encountered and was offered tea by a customs inspector named Yin Hsi. Yin Hsi encouraged him to compile his teachings into a single book so that future generations might benefit from his wisdom. This then became known as the ], a collection of Laozi's sayings. To honor Yin's generosity and its effect on the book's creation, a national custom of offering tea to guests began in ]. | |||

| ]: Chinese legends credit Shennong with the invention of tea.<ref name="laura2" />]] | |||

| People in ancient East Asia ate tea for centuries, perhaps even ], before ever consuming it as a beverage. They would nibble on the leaves raw, add them to ] or ], or ] them and chew them as ] is ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Driem |first1=George van |author1-link=George van Driem |title=The tale of tea: a comprehensive history of tea from prehistoric times to the present day |date=2019 |publisher=Brill |location=Leiden ; Boston |isbn=978-9004386259 |page=20 |language=en |chapter=The Primordial Origins of Tea}}</ref> | |||

| In 59 BC, Wang Bao wrote the first known book providing instructions on buying and preparing tea, establishing that, at this time, tea was not only a medicine but an important part of diet. | |||

| Tea drinking may have begun in the region of ], where it was used for medicinal purposes. It is believed that in ], "people began to boil tea leaves for consumption into a concentrated liquid without the addition of other leaves or herbs, thereby using tea as a bitter yet stimulating drink, rather than as a medicinal concoction."{{sfn|Heiss|Heiss|2007|pp=6–7}} | |||

| In 220, a famed physician and surgeon named ] wrote ''Shin Lun'', in which he describes tea's ability to improve mental functions: "to drink k'u t'u constantly makes one think better" | |||

| Chinese legends attribute the invention of tea to the mythical ] (in central and northern China) in 2737 BC, although evidence suggests that tea drinking may have been introduced from the southwest of China (Sichuan/Yunnan area).<ref name="laura2">{{Citation| last=Yee| first=L.K.| title=Tea's Wonderful History| publisher=The Chinese Historical and Cultural Project| quote=year 1996–2012| url=http://www.chcp.org/tea.html| access-date=17 June 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20020803115304/http://chcp.org/tea.html |archive-date=3 August 2002 }}</ref> The earliest written records of tea come from China. The word ''tú'' {{Wikt-lang|zh|荼}} appears in the '']'' and other ancient texts to signify a kind of "bitter vegetable" ({{lang|zh|苦菜}}), and it is possible that it referred to many different plants such as ], ], or ],{{sfn|Benn|2015|p=22}} as well as tea.{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|pp=264–65}} In the '']'', it was recorded that the ] people in Sichuan presented ''tu'' to the ] king. The ] later conquered the state of ] and its neighbour ], and according to the 17th century scholar ] who wrote in ''Ri Zhi Lu'' ({{lang|zh|日知錄}}): "It was after the Qin had taken Shu that they learned how to drink tea."{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|pp=29–30}} Another possible early reference to tea is found in a letter written by the ] general Liu Kun who requested that some "real tea" to be sent to him.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NT8J5qDjABIC&pg=PR18 |title=All the Tea in China |author=Kit Boey Chow |author2=Ione Kramer |pages=2–3 |publisher=Sinolingua |date=1990 |isbn=978-0-8351-2194-1 |access-date=21 May 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160831072957/https://books.google.com/books?id=NT8J5qDjABIC&pg=PR18&lpg=PR18 |archive-date=31 August 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| During the ] (589-618 AD) tea was introduced to ] by ] monks. | |||

| The earliest known physical evidence<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/archaeology/archaeologists-discover-worlds-oldest-tea-buried-with-ancient-chinese-emperor-a6805171.html|title=Archaeologists discover world's oldest tea buried with ancient Chinese emperor|work=]|publisher=Independent Print Limited|access-date=15 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171008011801/http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/archaeology/archaeologists-discover-worlds-oldest-tea-buried-with-ancient-chinese-emperor-a6805171.html|archive-date=8 October 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> of tea was discovered in 2016 in the mausoleum of ] in ], indicating that tea from the genus ''Camellia'' was drunk by ] emperors as early as the second century BC.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Earliest tea as evidence for one branch of the Silk Road across the Tibetan Plateau|volume=6|pages=18955|author=Houyuan Lu|journal=]|doi=10.1038/srep18955|pmid=26738699|pmc=4704058| date=7 January 2016|display-authors=etal|bibcode=2016NatSR...618955L}}</ref> The Han dynasty work "The Contract for a Youth", written by ] in 59 BC,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://phys.org/news/2016-01-world-oldest-tea-chinese-emperor.html|title=World's oldest tea found in Chinese emperor's tomb|publisher=]|date=28 January 2016|quote=The oldest written reference to tea is from the year 59 BC.|access-date=22 July 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160917190549/http://phys.org/news/2016-01-world-oldest-tea-chinese-emperor.html|archive-date=17 September 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> contains the first known reference to boiling tea. Among the tasks listed to be undertaken by the youth, the contract states that "he shall boil tea and fill the utensils" and "he shall buy tea at Wuyang".{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|pp=29–30}} The first record of tea cultivation is dated to this period, during which tea was cultivated on Meng Mountain ({{lang|zh|蒙山}}) near ].{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|pp=30–31}} Another early credible record of tea drinking dates to the 3rd century AD, in a medical text by the Chinese physician ], who stated, "to drink bitter t'u constantly makes one think better."<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AGaTAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA28 |title=The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug |author=Bennett Alan Weinberg, Bonnie K. Bealer |page=28 |publisher=Routledge |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-415-92722-2 |access-date=7 September 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160513051901/https://books.google.com/books?id=AGaTAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA28&lpg=PA28 |archive-date=13 May 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref> However, before the ], tea-drinking was primarily a southern Chinese practice centered in ].{{sfn|Benn|2015|p=42}} Tea was disdained by the ] aristocrats, who describe it as inferior to yogurt.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3qmwywEACAAJ&q=slaves'%20drink&pg=PA76 |title=The Jiankang Empire in Chinese and World History |author=Andrew Chittick |pages=75–76 |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2020 |isbn=9780190937546}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PASE4LVLzQ0C&q=yogurt&pg=PA22 |title=Culture and Power in the Reconstitution of the Chinese Realm, 200–600 |editor1=Scott Pearce |editor2=Audrey G. Spiro |editor3=Patricia Buckley Ebrey |page=22 |publisher=Harvard University Asia Center |year=2001 |isbn=0-674-00523-6}}</ref> It became widely popular during the Tang dynasty, when it spread to Korea, ], and Vietnam. '']'', a treatise on tea and its preparations, was written by the 8th century Chinese writer, ]. He was known to have influenced tea drinking on a large part in China.<ref name=":0">{{cite web |author=Miranda Brown |date=2 March 2022 |title=The Medieval Influencer Who Convinced the World to Drink Tea—Not Eat It |url=https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/eating-tea? |website=Atlas Obscura}}</ref> | |||

| ]'s statue in ]]] | |||

| The ] writer ](729-804 AD)'s ({{zh-stp|s=陆羽|t=陸羽|p=lùyǔ}}) ''Cha Jing'' ('']'') ({{zh-stp|s=茶经|t=茶經|p=chá jīng}}) is an early work on the subject. (See also ]) According to ''Cha Jing'' tea drinking was widespread. The book describes how tea plants were grown, the leaves processed, and tea prepared as a beverage. It also describes how tea was evaluated. The book also discusses where the best tea leaves were produced. Teas produced in this period were mainly ]s which were often used as currency, especially further from the center of the empire where coins lost their value. | |||

| ===Developments=== | |||

| During the ] (960-1279), production and preparation of all tea changed. The tea of Song included many loose-leaf styles (to preserve the delicate character favored by court society), but a new powdered form of tea emerged. Steaming tea leaves was the primary process used for centuries in the preparation of tea. After the transition from compressed tea to the powdered form, the production of tea for trade and distribution changed once again. The Chinese learned to process tea in a different way in the mid-13th century. Tea leaves were roasted and then crumbled rather than steamed. This is the origin of today's loose teas and the practice of brewed tea. | |||

| ] | |||

| Through the centuries, a variety of techniques for processing tea, and a number of different forms of tea, were developed. During the Tang dynasty, tea was steamed, then pounded and shaped into cake form,{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|pp=39–41}} while in the ], loose-leaf tea was developed and became popular. During the ] and ] dynasties, unoxidized tea leaves were first stirred in a hot dry pan, then rolled and air-dried, a process that stops the ] process that would have turned the leaves dark, thereby allowing tea to remain green. In the 15th century, ] tea, in which the leaves are allowed to partially oxidize before being heated in the pan, was developed.{{sfn|Benn|2015|p=42}} Western tastes, however, favoured the fully oxidized ], and the leaves were allowed to oxidize further. ] was an accidental discovery in the production of green tea during the Ming dynasty, when apparently careless practices allowed the leaves to turn yellow, which yielded a different flavour.{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|p=118}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Tea production in China, historically, was a laborious process, conducted in distant and often poorly accessible regions. This led to the rise of many apocryphal stories and legends surrounding the harvesting process. For example, one story that has been told for many years is that of a village where monkeys pick tea. According to this legend, the villagers stand below the monkeys and taunt them. The monkeys, in turn, become angry, and grab handfuls of tea leaves and throw them at the villagers.<ref name="Staunton">{{cite book|author=George Staunton|title=An Historical Account of the Embassy to the Emperor of China, Undertaken By Order of the King of Great Britain; Including the Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants; and Preceded By an Account of the Causes of the embassy and Voyage to China |year=1797|publisher=J. Stockdale|quote=The Chineſe perceiving theſe diſpoſitions in the monkey took advantage of the propenſities of the animal and converted them to life in a domeſtic ſtate which in that of nature were exerted to their annoyance.|pages=452}}</ref> There are products sold today that claim to be harvested in this manner, but no reliable commentators have observed this firsthand, and most doubt that it happened at all.<ref name="Fortune">{{cite book|author=Robert Fortune|year=1852|publisher=J. Murray|title=A Journey to the Tea Countries of China; including Sung-Lo and the Bohea Hills|quote=I should not like to assert that no tea is gathered on these hills by the agency of chains and monkeys but I think it may be safely affirmed that the quantity in such is small.|pages=237}}</ref> For many hundreds of years the commercially-used tea tree has been, in shape, more of a bush than a tree.<ref name="Cumming">{{cite book|author=Constance Frederica Gordon Cumming|title=Wanderings in China|publisher=W. Blackwood and Sons|pages=318}}</ref> "Monkey picked tea" is more likely a name of certain varieties than a description of how it was obtained.<ref name="Martin">{{cite book|author=Laura C. Martin|title=Tea: The Drink that Changed the World|publisher=Tuttle Publishing|isbn=0804837244|pages=133}}</ref> | |||

| ===Worldwide spread=== | |||

| In 1391, the ] court issued a decree that only loose tea would be accepted as a "]." As a result, loose tea production increased and processing techniques advanced. Soon, most tea was distributed in full-leaf, loose form and steeped in earthenware vessels. | |||

| {{See also|Arabic tea|Korean tea|Tea in Australia|Tea in France}} | |||

| ], ], before 1915]] | |||

| Tea was first introduced to Western priests and merchants in China during the 16th century, at which time it was termed ''chá''.<ref name="caff">{{cite book |author1=Bennett Alan Weinberg |author2=Bonnie K. Bealer |title=The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YdpL2YCGLVYC&pg=PA63 |year=2001 |publisher=Psychology Press |isbn=978-0-415-92722-2 |page=63 |access-date=10 January 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160427034134/https://books.google.com/books?id=YdpL2YCGLVYC&pg=PA63 |archive-date=27 April 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref> The earliest European reference to tea, written as ''chiai'', came from ''Delle navigationi e viaggi'' written by Venetian ] in 1545.{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|p=165}} The first recorded shipment of tea by a European nation was in 1607 when the Dutch East India Company moved a cargo of tea from ] to Java, then two years later, the Dutch bought the first assignment of tea which was from ] in Japan to be shipped to Europe.{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|p=106}} Tea became a fashionable drink in ] in the Netherlands, and the Dutch introduced the drink to ], ], and across the Atlantic to ] (New York).{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|p=169}} | |||

| === Japan === | |||

| ] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{main|History of tea in Japan}} | |||

| Tea use spread to Japan about the sixth century.<ref>{{Harvcolnb|Kiple|Ornelas|2000|p=4}}</ref> Tea became a drink of the religious classes in Japan when Japanese priests and envoys, sent to ] to learn about its culture, brought tea to Japan. Ancient recordings indicate the first batch of tea seeds were brought by a priest named {{nihongo|]|最澄|extra=767-822}} in 805 and then by another named {{nihongo|]|空海|extra=774-835}} in 806. It became a drink of the royal classes when {{nihongo|]|嵯峨天皇}}, the Japanese emperor, encouraged the growth of tea plants. Seeds were imported from China, and cultivation in Japan began. | |||

| In 1567, Russian people came in contact with tea when the ] ]s Petrov and Yalyshev visited China.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.apollotea.com/tea-articles/tea-history/15-russian-tea-history |title=Russian Tea History |website=www.apollotea.com |access-date=28 May 2019}}</ref> The Mongolian Khan donated to ] ] four ]s (65–70 kg) of tea in 1638.<ref name="T">{{cite book |title=] |publisher=Советская энциклопедия |year=1978 |pages=vol. 29, p. 11 }}</ref> According to ],<ref>Jeremiah Curtin, ''A Journey to Southern Siberia'', 1909, chapter one</ref> it was possibly in 1636<ref>Basil Dymytryshyn, ''Russia's Conquest of Siberia: A Documentary Record'', 1985, volume one, document 48 (he was an envoy that year, but the tea may have been given on a later visit to the Khan)</ref> that Vassili Starkov was sent as envoy to the ]. He was given 250 pounds of tea as a gift to the tsar. Starkov at first refused, seeing no use for a load of dead leaves, but the Khan insisted. Thus was tea introduced to Russia. In 1679, Russia concluded a treaty on regular tea supplies from China via ] in exchange for furs. It is today considered the ''de facto'' national beverage. | |||

| In 1191, the famous ] priest {{nihongo|]|栄西|extra=1141-1215}} brought back tea seeds to ]. Some of the tea seeds were given to the priest Myoe Shonin, and became the basis for Uji tea. The oldest tea specialty book in Japan, {{nihongo|''Kissa Yōjōki''|喫茶養生記|extra=''How to Stay Healthy by Drinking Tea''}}, was written by Eisai. Eisai was also instrumental in introducing tea consumption to the warrior class, which rose to political prominence after the ]. | |||

| ] on her arrival on 14 October 1843 with a cargo of tea.]] | |||

| Green tea became a staple among cultured people in Japan -- a brew for the gentry and the ]hood alike. Production grew and tea became increasingly accessible, though still a privilege enjoyed mostly by the upper classes. The ] was introduced from China in the 15th century by Buddhists as a semi-religious social custom.<ref name="columbia"/> The modern tea ceremony developed over several centuries by Zen Buddhist monks under the original guidance of the monk {{nihongo|]|千 利休|extra=1522-1591}}. In fact, both the beverage and the ceremony surrounding it played a prominent role in feudal diplomacy. | |||

| The first record of tea in English came from a letter written by Richard Wickham, who ran an ] office in Japan, writing to a merchant in Macao requesting "the best sort of chaw" in 1615. ], a traveller and merchant who came across tea in ] in 1637, wrote, "''chaa'' – only water with a kind of herb boyled in it".<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lXYFBQAAQBAJ&pg=PT25 |title=Tea: A Very British Beverage |author=Paul Chrystal |year=2014 |publisher=Amberley Publishing Limited |isbn=978-1-4456-3360-2 |access-date=5 September 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150928000518/https://books.google.com/books?id=lXYFBQAAQBAJ&pg=PT25&lpg=PT25 |archive-date=28 September 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>''Peter Mundy Merchant Adventurer'', 2011, ed. R.E. Pritchard, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford</ref> Tea was sold in a coffee house in London in 1657, ] tasted tea in 1660, and ] took the tea-drinking habit to the English court when she married ] in 1662. Tea, however, was not widely consumed in the British Isles until the 18th century and remained expensive until the latter part of that period. English drinkers preferred to add sugar and milk to black tea, and black tea overtook green tea in popularity in the 1720s.<ref>{{cite episode |title=Tea |series=] |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p004y24y |network=] |airdate=29 April 2004 |access-date=7 September 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150411023701/http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p004y24y |archive-date=11 April 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref> Tea smuggling during the 18th century led to the general public being able to afford and consume tea. The British government removed the tax on tea, thereby eliminating the smuggling trade, by 1785.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.tea.co.uk/page.php?id=98#masses |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090730000451/http://www.tea.co.uk/page.php?id=98 |archive-date=30 July 2009 |title=A Social History of the Nation's Favourite Drink |work=United Kingdom Tea Council}}</ref> In Britain and Ireland, tea was initially consumed as a luxury item on special occasions, such as religious festivals, wakes, and domestic work gatherings. The price of tea in Europe fell steadily during the 19th century, especially after Indian tea began to arrive in large quantities; by the late 19th century tea had become an everyday beverage for all levels of society.<ref name="Lysaght" /> The popularity of tea played a role in historical events – the ] of 1773 provoked the ] that escalated into the ]. The need to address the issue of British trade deficit because of the trade in tea resulted in the ]. The Qing ] had banned foreign products from being sold in China, decreeing in 1685 that all goods bought from China must be paid for in silver coin or bullion.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Goldstone|first=Jack A.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mOu_DQAAQBAJ&q=chinese+european+bullion&pg=PT365|title=Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World: Population Change and State Breakdown in England, France, Turkey, and China, 1600–1850; 25th Anniversary Edition|date=2016|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-315-40860-6|language=en}}</ref> Traders from other nations then sought to find another product, in this case opium, to sell to China to earn back the silver they were required to pay for tea and other commodities. The subsequent attempts by the Chinese Government to curtail the trade in opium led to war.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams and the Making of China |last=Lovell |first=Julia|authorlink=Julia Lovell |isbn=978-1-4472-0410-7 |year=2012 |publisher=Picador}}</ref> | |||

| In 1738, Soen Nagatani developed Japanese {{nihongo|'']''|煎茶}}, literally ''roasted tea'', which is an unfermented form of green tea. It is the most popular form of tea in Japan today. In 1835, Kahei Yamamoto developed {{nihongo|'']''|玉露}}, literally ''jewel dew'', by shading tea trees during the weeks leading up to harvesting. At the end of the ] (1868-1912), machine manufacturing of green tea was introduced and began replacing handmade tea. | |||

| ] | |||

| Chinese small-leaf-type tea was introduced into India in 1836 by the British in an attempt to break the Chinese monopoly on tea.<ref name="Sen" /> In 1841, ] brought seeds of ] from the ] region and experimented with planting tea in ]. The Alubari ] was opened in 1856, and ] began to be produced.{{sfn|Mair|Hoh|2009|p=214}} In 1848, ] was sent by the ] on a mission to China to bring the tea plant back to Great Britain. He began his journey in high secrecy as his mission occurred in the lull between the ] and the ].<ref name="Rose">{{cite book |author=Sarah Rose |title=For All the Tea in China |publisher=Penguin Books |pages=1–5, 89, 122, 197 |year=2010 |author-link=Sarah Rose}}</ref> The Chinese tea plants he brought back were introduced to the ], though most did not survive. The British had discovered that a different variety of tea was endemic to ] and the northeast region of India, which was then hybridized with Chinese small-leaf-type tea. Using Chinese planting and cultivation techniques, the British colonial government established a tea industry by offering land in Assam to any European who agreed to cultivate it for export.<ref name="Sen" /> Tea was originally consumed only by ]; however, it became widely popular in India in the 1950s because of a successful advertising campaign by the India Tea Board.<ref name="Sen">{{cite book |author=Colleen Taylor Sen|title=Food Culture in India |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YIyV_5wrplMC&pg=PA26 |year=2004 |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |isbn=978-0-313-32487-1 |page=26 |quote=Ironically, it was the British who introduced tea drinking to India, initially to anglicized Indians. Tea did not become a mass drink there until the 1950s when the India Tea Board, faced with a surplus of low-grade tea, launched an advertising campaign to popularize it in the north, where the drink of choice was milk. |access-date=10 January 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160424065113/https://books.google.com/books?id=YIyV_5wrplMC&pg=PA26 |archive-date=24 April 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref> The British introduced tea industry to Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) in 1867.<ref name="taylor-AU">{{cite web|url=http://www1.american.edu/ted/ceylon-tea.htm|title=TED Case Studies – Ceylon Tea|publisher=American University, Washington, DC|access-date=27 November 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150223084443/http://www1.american.edu/ted/ceylon-tea.htm|archive-date=23 February 2015|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| == Chemical composition == | |||

| {{ |

{{See also|Phenolic content in tea}} | ||

| ]'', Korean tea ceremony]] | |||

| The first historical record documenting the offering of tea to an ancestral god describes a rite in the year 661 in which a tea offering was made to the spirit of ], the founder of the ] Kingdom (42-562). Records from the ] Dynasty (918-1392) show that tea offerings were made in Buddhist temples to the spirits of revered monks. | |||

| Physically speaking, tea has properties of both a ] and a ]. It is a solution of the water-soluble compounds extracted from the tea leaves, such as the polyphenols and amino acids. Tea infusions are among most consumed beverages globally.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Yang|first1=Ziyin|last2=Baldermann|first2=Susanne|last3=Watanabe|first3=Naoharu|date=1 October 2013|title=Recent studies of the volatile compounds in tea|url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S096399691300104X|journal=Food Research International |series=Tea – from bushes to mugs: composition, stability and health aspects |volume=53 |issue=2 |pages=585–599 |doi=10.1016/j.foodres.2013.02.011 |issn=0963-9969}}</ref> | |||

| The latitude of Korea is high and the climate is unsuitable for tea growing; production of tea is slight, the quality was bad and the taste was unpalatable. The Koreans therefore imported tea leaf, chiefly from ]. | |||

| ] makes up about 3% of tea's dry weight, which translates to between 30 and 90 milligrams per {{convert|250|mL|usfloz|adj=on|frac=2}} cup depending on the type, brand,<ref>{{cite book |author1=Weinberg, Bennett Alan |author2=Bealer, Bonnie K. |name-list-style=amp |title=The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug |url=https://archive.org/details/worldofcaffeines00benn |url-access=registration |publisher=Routledge |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-415-92722-2 |page=}}</ref> and brewing method.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Hicks MB, Hsieh YP, Bell LN |title=Tea preparation and its influence on methylxanthine concentration |journal=Food Research International |volume=29 |issue=3–4 |pages=325–330 |year=1996 |doi=10.1016/0963-9969(96)00038-5 |url=http://www2.hcmuaf.edu.vn/data/lhquang/file/Tea1/Tea%20preparation%20and%20its%20influence%20on%20methylxanthine.pdf |access-date=13 May 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130203132842/http://www2.hcmuaf.edu.vn/data/lhquang/file/Tea1/Tea%20preparation%20and%20its%20influence%20on%20methylxanthine.pdf |archive-date=3 February 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> A study found that the caffeine content of one gram of black tea ranged from 22 to 28 mg, while the caffeine content of one gram of green tea ranged from 11 to 20 mg, reflecting a significant difference.<ref>{{cite journal |pmc=3459493 |pmid=23055579 |doi=10.4103/0972-124X.99256 |volume=16 |issue=2 |title=Green tea: A boon for periodontal and general health |year=2012 |journal=Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology |pages=161–167 |vauthors=Chatterjee A, Saluja M, Agarwal G, Alam M |doi-access=free }}</ref> Tea contains small amounts of ] and ], which are ]s and ]s, similar to caffeine.<ref>{{cite journal |pmid=1614995 |year=1992 |last1=Graham |first1=HN |title=Green tea composition, consumption, and polyphenol chemistry |volume=21 |issue=3 |pages=334–350 |journal=Preventive Medicine |doi=10.1016/0091-7435(92)90041-f}}</ref> | |||

| During the ] (1392-1910), the royal Yi family and the aristocracy used tea for simple rites. The "Day Tea Rite" was a common daytime ceremony, whereas the "Special Tea Rite" was reserved for specific occasions. Toward the end of the Joseon Dynasty, commoners joined the trend and used tea for ancestral rites, following the Chinese example based on Zhu Xi's text formalities of Family. | |||

| ] | |||

| Stoneware was common, ceramic more frequent, mostly made in provincial kilns, with porcelain rare, imperial porcelain with dragons the rarest. The earliest kinds of tea used in tea ceremonies were heavily pressed cakes of black tea, the equivalent of aged ] still popular in China. However, importation of tea plants by Buddhist monks brought a more delicate series of teas into Korea, and the ]. Green tea, "chaksol" or "chugno," is most often served. However other teas such as "Byeoksoryung" Chunhachoon, Woojeon, Jakseol, Jookro, Okcheon, as well as native ], ] leaf tea, or ] tea may be served at different times of the year. | |||

| The ] in tea can be attributed to the presence of ]s. These are the most abundant compounds in tea leaves, making up 30–40% of their composition.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Harbowy |first=ME |year=1997 |title=Tea Chemistry |journal=Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences |volume=16 |issue=5 |pages=415–480 |doi=10.1080/713608154}}</ref> Polyphenols in tea include ]s, ] (EGCG), and other ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ferruzzi |first1=MG |year=2010 |title=The influence of beverage composition on delivery of phenolic compounds from coffee and tea |journal=Physiol Behav |volume=100 |issue=1 |pages=33–41 |doi=10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.01.035 |pmid=20138903|s2cid=207373774 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Williamson G, Dionisi F, Renouf M |year=2011 |title=Flavanols from green tea and phenolic acids from coffee: critical quantitative evaluation of the pharmacokinetic data in humans after consumption of single doses of beverages |journal=Mol Nutr Food Res |volume=55 |issue=6 |pages=864–873 |pmid=21538847 |doi=10.1002/mnfr.201000631}}</ref> Although there has been preliminary ] on whether green or black teas may protect against various human diseases, there is no evidence that tea polyphenols have any effect on health or lowering disease risk.<ref name="nccih">{{cite web |url=http://nccih.nih.gov/health/greentea |publisher=National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD |title=Green Tea |date=2014 |access-date=25 October 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150402153347/https://nccih.nih.gov/health/greentea |archive-date=2 April 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/LabelingNutrition/ucm073992.htm#gtea |title=Summary of Qualified Health Claims Subject to Enforcement Discretion:Green Tea and Cancer |publisher=Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services |date=October 2014 |access-date=25 October 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141015104050/http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/LabelingNutrition/ucm073992.htm#gtea |archive-date=15 October 2014 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| === Taiwan === | |||

| Taiwan is famous for the making of Oolong tea and green tea, as well as many western-styled teas. ] or "Zhen Zhu Nai Cha" is black tea mixed with sweetened condensed milk and tapioca. Since the island was known to Westerners for many centuries as ''Formosa'' — short for the Portuguese ''Ilha Formosa'', or "beautiful island" — tea grown in Taiwan is often identified by that name. | |||

| == Health effects == | |||

| {{Main|Health effects of tea}} | |||

| ], ].]] | |||

| Although health benefits have been assumed throughout the history of '']''] consumption, there is no high-quality evidence showing that tea consumption gives significant benefits other than possibly increasing alertness, an effect caused by ] in the tea leaves.<ref name="medline">{{cite web |date=30 November 2017 |title=Black tea |url=https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/natural/997.html |access-date=27 February 2018 |publisher=MedlinePlus, US National Library of Medicine}}</ref><ref name="nccih2">{{cite web |date=30 November 2016 |title=Green tea |url=https://nccih.nih.gov/health/greentea |access-date=27 February 2018 |publisher=National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US National Institutes of Health}}</ref> In ] conducted in the early 21st century, it was found there is no scientific evidence to indicate that consuming tea affects any disease or improves health.<ref name="medline" /> | |||

| Black and green teas contain no ] in significant amounts, with the exception of the ] ], at 0.5 mg per cup or 26% of the ] (RDI).<ref>{{cite web |date=2014 |title=Tea, brewed, prepared with tap water , one cup, USDA Nutrient Tables, SR-21 |url=http://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/beverages/3967/2 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141026201138/http://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/beverages/3967/2 |archive-date=26 October 2014 |access-date=25 October 2014 |publisher=Conde Nast}}</ref> ] is sometimes present in tea; certain types of "brick tea", made from old leaves and stems, have the highest levels, enough to pose a health risk if much tea is drunk, which has been attributed to high levels of fluoride in soils, acidic soils, and long brewing.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Fung KF, Zhang ZQ, Wong JW, Wong MH |year=1999 |title=Fluoride contents in tea and soil from tea plantations and the release of fluoride into tea liquor during infusion |journal=Environmental Pollution |volume=104 |issue=2 |pages=197–205 |doi=10.1016/S0269-7491(98)00187-0}}</ref> | |||

| The importing of tea into Britain began in the 1660s with the marriage of ] with the ] princess ] where she brought to the court the habit of drinking tea.<ref name="bbc">(In Our Time, BBC Radio 4, 29 April 2004)</ref> In the same year ] records drinking "a china drink of which I had never drunk before".<ref name="bbc" /> It is probable that early imports came via ] or through sailors on eastern boats.<ref name="bbc" /> | |||

| == Cultivation and harvesting == | |||

| Regular trade began in ] (Canton).<ref name="bbc" /> Trade was controlled by two monopolies: the Chinese ''Hongs'' (trading companies) and the ].<ref name="bbc" /> The Hongs acquired tea from 'the tea men' who had an elaborate supply chain into the mountains and provinces where the tea was grown.<ref name="bbc" /> | |||

| {{anchor|Cultivation and harvesting}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ''Camellia sinensis'' is an evergreen plant that grows mainly in ] and ] climates.<ref name="hort.purdue" /> Some varieties can tolerate ]s and are cultivated as far north as ] in England,<ref>{{cite news |last=Levin |first=Angela |date=20 May 2013 |title=Welcome to Tregothnan, England's only tea estate |newspaper=] |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/foodanddrink/10061426/Welcome-to-Tregothnan-Englands-only-tea-estate.html |access-date=5 December 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131214014053/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/foodanddrink/10061426/Welcome-to-Tregothnan-Englands-only-tea-estate.html |archive-date=14 December 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> ] in Scotland,<ref name=ti-2014nov17>{{cite news |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/features/the-worlds-first-scottish-tea-at-10-a-cup-9866437.html |title=The world's first Scottish tea (at £10 a cup) |website=] |date=17 November 2014 |first=Kate |last=Hilpern |access-date=15 September 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171008130141/https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/features/the-worlds-first-scottish-tea-at-10-a-cup-9866437.html |archive-date=8 October 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> ] in the ],<ref>{{cite web |title=Tea |url=http://69.93.14.225/wscpr/LibraryDocs/Tea2010.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110810214327/http://69.93.14.225/wscpr/LibraryDocs/Tea2010.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=10 August 2011 |work=The Compendium of Washington Agriculture |publisher=Washington State Commission on Pesticide Registration |year=2010 |access-date=26 April 2011 |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.-->}}</ref> and ] in Canada.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://blogs.vancouversun.com/2013/05/05/tea-farm-on-vancouver-island-a-canadian-first/ |title=Tea farm on Vancouver Island, a Canadian first |newspaper=] |date=5 May 2013 |access-date=26 May 2014 |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140527214442/http://blogs.vancouversun.com/2013/05/05/tea-farm-on-vancouver-island-a-canadian-first/ |archive-date=27 May 2014 |url-status=live}}</ref> In the Southern Hemisphere, tea is grown as far south as ] in Tasmania<ref>{{cite news |url=http://prelive.themercury.com.au/article/2013/08/13/385535_tasmania-news.html |title=Tassie tea crop brewing |newspaper=] |date=13 August 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140311120146/http://prelive.themercury.com.au/article/2013/08/13/385535_tasmania-news.html |archive-date=11 March 2014 |first=Jennifer |last=Crawley}}</ref><ref>{{cite episode |url=http://www.abc.net.au/tv/cookandchef/txt/s2404570.htm |title=Episode 36 – Produce of Two Islands |series=] |number=36 |date=29 October 2008 |network=] |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |access-date=24 January 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150215032023/http://www.abc.net.au/tv/cookandchef/txt/s2404570.htm |archive-date=15 February 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref> and ] in New Zealand.<ref name=nzh-2013aug17>{{cite news |url=https://www.nzherald.co.nz/waikato-news/news/tea-growing-is-tough-going/XCPAATJPQKKS7QFZ64WFSV2ILI/ |title=Tea growing is tough going |work=] |date=17 August 2013 |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |access-date=24 January 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240222192713/https://www.nzherald.co.nz/waikato-news/news/tea-growing-is-tough-going/XCPAATJPQKKS7QFZ64WFSV2ILI/|archive-date=22 February 2024|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The East India Company brought back many products, of which tea was just one, but it was to prove one of the most successful.<ref name="bbc" /> It was initially promoted as a medicinal beverage or tonic.<ref name="bbc" /> By the end of the seventeenth century tea was taken as a drink, albeit mainly by the aristocracy.<ref name="bbc" /> In 1690 nobody would have predicted that by 1750 tea would be the national drink.<ref name="bbc" /> | |||

| Tea plants are propagated from seed and cuttings; about 4 to 12 years are needed for a plant to bear seed and about three years before a new plant is ready for harvesting.<ref name="hort.purdue">{{cite web |url=http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/duke_energy/camellia_sinensis.html |title=Camellia Sinensis |publisher=Purdue University Center for New Crops and Plants Products |access-date=26 October 2010 |date=3 July 1996 |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100924055240/http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/duke_energy/Camellia_sinensis.html |archive-date=24 September 2010 |url-status=live}}</ref> In addition to a ] climate or warmer, tea plants require at least 127 cm (50 in) of rainfall per year and prefer ].<ref>{{cite book |title=Camellias: A Practical Gardening Guide |last1=Rolfe |first1=Jim |first2=Yvonne |last2=Cave |name-list-style=amp |year=2003 |publisher=Timber Press |isbn=978-0-88192-577-7}}</ref> Many high-quality tea plants are cultivated at elevations of up to {{convert|1500|m|ft|abbr=on}} above sea level. Though at these heights the plants grow more slowly, they acquire a better flavour.<ref>{{cite book |title=Tea Cuisine: A New Approach to Flavoring Contemporary and Traditional Dishes |last=Pruess |first=Joanna |year=2006 |publisher=Globe Pequot |isbn=978-1-59228-741-3}}</ref> | |||

| The escalation of tea importation and sales over the period 1690 to 1750 is mirrored closely by the increase in importation and sales of ]: the British were not drinking just tea but ''sweet'' tea.<ref name="bbc" /> Thus, two of Britain's trading triangles were to meet within the cup: the sugar sourced from Britain's trading triangle encompassing Britain, Africa and the West Indies and the tea from the triangle encompassing Britain, India and China.<ref name="bbc" /> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Britain had to pay China for its tea, but China had little need of British goods, so much of it was paid for with silver bullion. Critics of tea at this time would point to the damage caused to Britain's wealth by this loss of bullion.<ref name="bbc" /> As an alternative, Britain began producing ] in India and forced China to trade tea for opium as part of several treaties after the ]. Tea became an important lubricant of Britain's global trade, contributing to Britain's global dominance by the end of the eighteenth century. To this day tea is seen as a symbol of 'Britishness', but also, to some, as a symbol of ] ].<ref name="bbc" />. The ] section of the paralympic handover in Beijing included tea as part of the routine{{Clarifyme|date=October 2008}}, such is the strong connections made between Britain and tea. | |||

| Two principal varieties are used: ''Camellia sinensis'' var. ''sinensis,'' which is used for most Chinese, Formosan and Japanese teas, and ''C. sinensis'' var. ''assamica,'' used in ] and most Indian teas (but not Darjeeling). Within these botanical varieties, many ] and modern clonal varieties are known. Leaf size is the chief criterion for the classification of tea plants, with three primary classifications being:<ref name=Mondal /> ] type, characterised by the largest leaves; China type, characterised by the smallest leaves; and Cambodian type, characterised by leaves of intermediate size. The Cambodian-type tea (''C. assamica'' subsp. ''lasiocaly'') was originally considered a type of Assam tea. However, later genetic work showed that it is a hybrid between Chinese small-leaf tea and Assam-type tea.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Wambulwa |first1=M. C. |last2=Meegahakumbura |first2=M. K. |last3=Chalo |first3=R.|title=Nuclear microsatellites reveal the genetic architecture and breeding history of tea germplasm of East Africa |journal=Tree Genetics & Genomes |date=February 2016 |volume=12 |issue=1 |doi=10.1007/s11295-015-0963-x |s2cid=255132393 |url=https://www.academia.edu/28051971|url-access=registration|display-authors=etal}}</ref> Darjeeling tea appears to be a hybrid between Chinese small-leaf tea and Assam-type large-leaf tea.<ref name="Meegahakumbura 2"/> | |||

| === United States of America === | |||

| While ] is more popular, hot brewed black tea is enjoyed both with meals and as a refreshment by much of the population. ] is consumed throughout similarly. In the ] states ], sweetened with large amounts of sugar or an artificial sweetener and chilled is the fashion. Outside the South, "Sweet Tea" is sometimes found in restaurants or in the home, but primarily because of a culture migration and commercialization. | |||

| ], ]]] | |||

| The American speciality tea market has quadrupled in the years from 1993-2008, now being worth $6.8 billion a year.<ref> Times Online, Retrieved 17 February 2008.</ref> | |||

| A tea plant will grow into a tree of up to {{convert|16|m|ft|abbr=on}} if left undisturbed,<ref name="hort.purdue" /> but cultivated plants are generally pruned to waist height for ease of plucking. The short plants bear more new shoots which provide new and tender leaves and increase the quality of the tea.<ref name="Tea Cultivation">{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/585098/tea |title=Tea production |access-date=1 June 2007 |encyclopedia=] |first=Campbell Ronald |last=Harler |date=26 August 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080430063121/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/585098/tea |archive-date=30 April 2008 |url-status=live }}</ref> Only the top {{convert|1|-|2|in|cm|round=0.5|order=flip}} of the mature plant are picked. These buds and leaves are called 'flushes'.<ref>{{cite book |first=Elizabeth S. |last=Hayes |title=Spices and Herbs: Lore and Cookery |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=htsIVCwRsEcC |publisher=Courier Dover Publications |year=1980 |isbn=978-0-486-24026-8 |page=74}}</ref> A plant will grow a new flush every 7 to 15 days during the growing season. Leaves that are slow in development tend to produce better-flavoured teas.<ref name="hort.purdue" /> Several teas are available from specified flushes; for example, Darjeeling tea is available as first flush (at a premium price), second flush, monsoon and autumn. Assam second flush or "tippy" tea is considered superior to first flush, because of the gold tips that appear on the leaves. | |||

| ], India]] | |||

| Pests that can afflict tea plants include mosquito bugs, genus '']'', which are ] and not to be confused with ] ('mosquitos'). Mosquito bugs can damage leaves both by sucking plant materials, and by the laying of eggs (oviposition) within the plant. Spraying with synthetic ]s may be deemed appropriate.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Somnath Roy |author2=Narayanannair Muraleedharan |author3=Ananda Mukhapadhyay |author4=Gautam Handique | date=24 April 2015 | title= The tea mosquito bug, Helopeltis theivora Waterhouse (Heteroptera: Miridae): its status, biology, ecology and management in tea plantations | journal=International Journal of Pest Management, 61:3 | volume=61 | issue=3 | pages=179–197 | doi=10.1080/09670874.2015.1030002 | s2cid=83481846 }}</ref> Other pests are Lepidopteran leaf feeders and various ]. | |||

| === India === | |||

| {{see also|Assam tea|Darjeeling tea|Nilgiri tea}} | |||

| According to the Encyclopedia Britannica (2008): "In 1824 tea plants were discovered in the hills along the frontier between Burma and the Indian state of Assam. The British introduced '']'' into India in 1836 and into Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1867. At first they used seeds from China, but later seeds from the Assam plant were used."<ref>tea. (2008). Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica 2008 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.</ref> | |||

| == Production == | |||

| India was the top producer of tea for nearly a century, but was displaced by China as the top tea producer in the 21st century.<ref name=Sanyal>{{Harvcoltxt|Sanyal|2008}}</ref> Indian tea companies have acquired a number of iconic foreign tea enterprises including British brands ] and ].<ref name=Sanyal/> India is also the world's largest tea-drinking nation.<ref name=Sanyal/> However, the per capita consumption of tea in India remains a modest 750 grams per person every year due to the large population base and high poverty levels.<ref name=Sanyal/> | |||

| {| class="wikitable floatright" | |||

| === Sri Lanka/Ceylon === | |||

| |+Tea production – 2022 | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Ceylon tea (black)}} | |||

| ] is renowned for its high quality tea and as the third biggest tea producing country globally, has a production share of 9% in the international sphere, and one of the world's leading exporters with a share of around 19% of the global demand. The total extent of land under tea cultivation has been assessed at approximately 187,309 hectares. | |||

| The plantations started by the British were initially taken over by the government in the 1960s, but have been privatized and are now run by 'plantation companies' which own a few 'estates' or tea plantations each. | |||

| Ceylon tea is divided into 3 groups as Upcountry, Mid country and Low country tea based on the geography of the land on which it is grown. Today, Ceylon tea is known as one of the best in the world.{{Fact|date=October 2008}} | |||

| ] | |||

| === Tea spreads to the world === | |||

| The earliest record of tea in a more ] writing is said to be found in the statement of an Arabian traveler, that after the year 879 the main sources of revenue in ] were the duties on salt and tea. ] records the deposition of a Chinese minister of finance in 1285 for his arbitrary augmentation of the tea taxes. The travelers Giovanni Batista ] (1559), L. Almeida (1576), Maffei (1588), and Taxiera (1610) also mentioned tea. In 1557, ] established a trading port in ] and word of the Chinese drink "ch'a" spread quickly, but there is no mention of them bringing any samples home. In the early 17th century, a ship of the ] brought the first green tea leaves to ] from ]. Tea was known in ] by 1636. It enjoyed a brief period of popularity in ] around 1648. The history of tea in ] can also be traced back to the seventeenth century. Tea was first offered by China as a gift to Czar ] in 1618. The Russian ambassador tried the drink; he did not care for it and rejected the offer, delaying tea's Russian introduction by fifty years. In 1689, tea was regularly imported from China to Russia via a caravan of hundreds of camels traveling the year-long journey, making it a precious commodity at the time. Tea was appearing in ] ] by 1657 but never gained much esteem except in coastal areas such as ].<ref>Book of Tea By Kakuzō Okakura (pages 5 - 6). Published 1964. Courier Dover Publications. Sociology. 94 pages. ISBN 0486200701</ref> Tea first appeared publicly in England during the 1650s, where it was introduced through coffee houses. From there it was introduced to British colonies in America and elsewhere. | |||

| == Potential effects of tea on health == | |||

| {{main|Potential effects of tea on health}} | |||

| According to {{Harvtxt|Mondal|2007|pp=519–520}}: | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| Tea leaves contain more than 700 chemicals, among which the compounds closely related to human health are flavanoides, amino acids, vitamins (C, E and K), caffeine and polysaccharides. Moreover, tea drinking has recently proven to be associated with cell-mediated immune function of the human body. Tea plays an important role in improving beneficial intestinal microflora, as well as providing immunity against intestinal disorders and in protecting cell membranes from oxidative damage. Tea also prevents dental caries due to the presence of fluorine. The role of tea is well established in normalizing blood pressure, lipid depressing activity, prevention of coronary heart diseases and diabetes by reducing the blood-glucose activity. Tea also possesses germicidal and germistatic activities against various ] and ] human pathogenic bacteria. Both green and black tea infusions contain a number of antioxidants, mainly catechins that have anti-carcinogenic, anti-mutagenic and anti-tumor properties. | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| ==Etymology and cognates in other languages== | |||

| The ] for tea is 茶, but it is pronounced differently in the various ] dialects. Two pronunciations have made their way into other languages around the world<ref>{{ citation | |||

| | title=The World Atlas of Language Structures Online | |||

| | contribution=Feature/Chapter 138: Tea | |||

| | first=Östen | |||

| | last=Dahl | |||

| | publisher=Max Planck Digital Library | |||

| | url=http://wals.info/feature/138 | |||

| | accessdate=2008-06-04 | |||

| }}</ref>. One is ''tê'', which comes from the ], spoken around the ] of ] (Amoy). This pronunciation is believed to come from the old words for tea 梌 (tú) or 荼 (tú). The other is ''chá'', used by the ] spoken around the ports of ] (Canton), ], ], and in ] communities, as well as in the ] of northern China. This term was used in ancient times to describe the first flush harvest of tea. Yet another different pronunciation is ''zu'', used in the ] spoken around ]. The words for tea in Korea and Japan are 차 and 茶(ちゃ), respectively. Both are transliterated as ''cha''. (In Japanese, it is sometimes 御茶(おちゃ) or ''ocha'', which is more polite.) | |||

| === The derivatives from ''tê''=== | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| !width="85px"|Language | |||

| !width="85px"|Name | |||

| !width="85px"|Language | |||

| !width="85px"|Name | |||

| !width="85px"|Language | |||

| !width="85px"|Name | |||

| !width="85px"|Language | |||

| !width="85px"|Name | |||

| !width="85px"|Language | |||

| !width="85px"|Name | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! style="background:#ddf;"| Country | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| ! style="background:#ddf;"|Million<br /> tonnes | |||

| |''tee'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ], ] | |||

| |''te'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''cha'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''té'' or ''thé'' <sub>(1)</sub> | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''te'' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{CHN}}||{{right|14.53}} | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''thee'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tea'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''teo'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tee'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''te'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tee'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''thé'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tee'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''té'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''Tee'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |תה, ''te'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tea'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''te'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''teh'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tae'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tè'' or ''thè'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tèh'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | scientific ] | |||

| |''thea'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tēja'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tiè'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''arbata'' <sub>(2)</sub> | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''Tee'' or ''Tei'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''teh'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''te'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tè'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''herbata'' <sub>(3)</sub> | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tea'',''chá'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tì'', ''teatha'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''thé'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''té'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tea'' ~ | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''entèh'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''te'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |தேநீர் ''thenīr'' (nīr = water) "theyila" means "tea leaf" (ila=leaf) | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |తేనీళ్ళు ''tēnīru'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''te'' | |||

| |} | |||

| * Note: <sub>(1)</sub> ''té'' or ''thé'', but these words are used only when describing a ], as in "lipové thé" (limeflower tea) ; ''čaj'' is used for "tea" in modern Czech, as explained in the next table. see <sub>(4)</sub>. In case of <sub>(2), (3)</sub>, ''arbata'' and ''herbata'' are from ] ''herba thea''. | |||

| The word ''tea'' came into the ] from the ] word for tea (]), which is pronounced ''tê'' in the ] ]. | |||

| === The derivatives from ''cha'' or ''chai'' === | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| !width="85px"|Language | |||

| !width="85px"|Name | |||

| !width="85px"|Language | |||

| !width="85px"|Name | |||

| !width="85px"|Language | |||

| !width="85px"|Name | |||

| !width="85px"|Language | |||

| !width="85px"|Name | |||

| !width="85px"|Language | |||

| !width="85px"|Name | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{IND}}||{{right|5.97}} | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''çaj'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |ሻይ ''shai'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |شاي ''shai'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''saah'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |pronounced ''chai'' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{flagicon|Kenya}} ]||{{right|2.33}} | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''çay'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |চা ''cha'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''čaj'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |чай ''chai'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''cha'' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{flagicon|Sri Lanka}} ]||{{right|1.40}} | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tsa'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''čaj'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''čaj'' <sub>(4)</sub> | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''char'', slang | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |ჩაი, ''chai'' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{TUR}}||{{right|1.30}} | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |τσάι ''tsái'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |ચા ''cha'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |चाय ''chai'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''tsa'', or ''i-tsa'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |{{lang|ja|茶}}, {{lang|ja|ちゃ}}, ''cha'' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{VNM}}||{{right|1.12}} | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''ಚಹಾ Chaha'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |шай ''shai'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''sha'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''cha'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |茶,차 ''cha'' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{IDN}}||{{right|0.60}} | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |чај, ''čaj'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |"chaaya" | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |चहा ''chahaa'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |цай, ''tsai'' | |||

| | bgcolor="eeeeee" | ] | |||

| |''chiya'' चिया | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{BAN}}||{{right|0.44}} | |||