This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Straight-Outta-Negros-0013 (talk | contribs) at 07:30, 1 June 2017 (→Names: Minor fixes...). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 07:30, 1 June 2017 by Straight-Outta-Negros-0013 (talk | contribs) (→Names: Minor fixes...)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Korean | |

|---|---|

| 한국어 (韓國語) (South Korea) 조선말 (朝鮮말) (North Korea) | |

| Pronunciation | Template:IPA-ko / Template:IPA-ko |

| Native to | Korea |

| Ethnicity | Korean people |

| Native speakers | 77,233,270 (2010) |

| Language family | Koreanic

|

| Early forms | Proto-Korean |

| Standard forms | |

| Dialects | Korean dialects |

| Writing system | Hangul (primary) Hanja Romaja Korean Braille |

| Official status | |

| Official language in | |

| Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | The Language Research Institute, Academy of Social Science 사회과학원 어학연구소 / 社會科學院 語學研究所 (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) National Institute of the Korean Language 국립국어원 / 國立國語院 (Republic of Korea) China Korean Language Regulatory Commission 중국조선어규범위원회 中国朝鲜语规范委员会 (People's Republic of China) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ko |

| ISO 639-2 | kor |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:kor – Modern Koreanjje – Jejuokm – Middle Koreanoko – Old Koreanoko – Proto Korean |

| Linguist List | okm Middle Korean |

oko Old Korean | |

| Glottolog | kore1280 |

| Linguasphere | 45-AAA-a |

Countries with native Korean-speaking populations (established immigrant communities in green). Countries with native Korean-speaking populations (established immigrant communities in green). | |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. | |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Korea |

|---|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

The Korean language (한국어/조선말, see below) is the official and national language of both Koreas: the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and the Republic of Korea, with different standardized official forms used in each territory. It is also one of the two official languages in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture and Changbai Korean Autonomous County of the People's Republic of China. Approximately 80 million people worldwide speak Korean.

Historical and modern linguists classify Korean as a language isolate; however, it does have a few extinct relatives, which together with Korean itself and the Jeju language (spoken in the Jeju Province and considered somewhat distinct) form the Koreanic language family. This implies that Korean is not an isolate, but a member of a small family. The idea that Korean belongs to the controversial Altaic language family is discredited in academic research. There is still debate about a relation to Dravidian languages and on whether Korean and Japanese are related to each other. The Korean language is agglutinative in its morphology and SOV in its syntax.

History

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Modern Korean descends from Middle Korean, which in turn descends from Old Korean, which descends from the language spoken in Prehistoric Korea (labeled Proto-Korean), whose nature is debated, in part because Korean genetic origins are controversial. A relation of Korean (together with its extinct relatives which form the Koreanic family) with Japonic languages has been proposed by linguists like William George Aston and Samuel Martin. Roy Andrew Miller and others suggested or supported the inclusion of Koreanic and Japonic languages in the purported Altaic family (a macro-family that would comprise Tungusic, Mongolian and Turkic families); the Altaic hypothesis has since been largely rejected by most linguistic specialists.

Chinese characters arrived in Korea together with Buddhism during the pre-Three Kingdoms period. It was adapted for Korean and became known as hanja, and remained as the main script for writing Korean through over a millennium alongside various phonetic scripts that were later invented such as idu and gugyeol. Mainly privileged elites were educated to read and write in hanja, however, and most of the population was illiterate. In the 15th century, King Sejong the Great felt that the hanja were not adequate to write Korean and this was the cause of its very restricted use, so (with a likely help of the Hall of Worthies) he developed an alphabetic featural writing system known today as hangul, which was designed to either aid in reading hanja or replace hanja entirely. Introduced in the document Hunminjeongeum, it became popular and increased literacy in Korea, but due to its suppression by the aristocratic class during the Joseon era, hangul as a national script truly took hold shortly before the fall of the Korean Empire and during the Japanese occupation of Korea. Following World War II and the Japanese withdrawal from Korea, it was the de facto language of the various Korean political parties, and following the establishment of North and South Korea, hangul became the official script for both. Today, the hanja are largely unused in everyday life, but in South Korea they experience revivals on artistic works and are important in historic and/or linguistic studies of Korean.

Since the Korean War, through 70 years of separation, North–South differences have developed in standard Korean, including variations in pronunciation, verb inflection and vocabulary chosen.

Names

The Korean names for the language are based on the names for Korea used in North Korea and South Korea.

In South Korea, the Korean language is referred to by many names including hanguk-eo ("Korean language"), hanguk-mal ("Korean speech") and uri-mal ("our language"). In "hanguk-eo" and "hanguk-mal", the first part of the word, "hanguk", refers to the Korean nation while "-eo" and "-mal" mean "language" and "speech", respectively. Korean is also simply referred to as guk-eo, literally "national language". This name is based on the same Han characters, meaning "nation" + "language" ("國語"), that are also used in Taiwan and Japan to refer to their respective national languages.

In North Korea and China, the language is most often called Chosŏn-mal, or more formally, Chosŏn-ŏ. The English word "Korean" is derived from Goryeo, which is thought to be the first Korean dynasty known to the Western nations. Korean people in the former USSR refer to themselves as Koryo-saram and/or Koryo-in (literally, "Koryo/Goryeo person(s)"), and call the language Koryo-mar.

In mainland China, following the establishment of diplomatic relations with South Korea in 1992, the term Cháoxiǎnyǔ or the short form Cháoyǔ has normally been used to refer to the standard language of North Korea and Yanbian, whereas Hánguóyǔ or the short form Hányǔ is used to refer to the standard language of South Korea.

Some older English sources also use the spelling "Corea" to refer to the nation, and its inflected form for the language, culture and people, "Korea" becoming more popular in the late 1800s according to Google's NGram English corpus of 2015.

Classification

The majority of historical and modern linguists classify Korean as a language isolate.

There are still a small number who think that Korean might be related to the now discredited Altaic family, but linguists agree today that typological resemblances cannot be used to prove genetic relatedness of languages, as these features are typologically connected and easily borrowed from one language to the other. Such factors of typological divergence as Middle Mongolian's exhibition of gender agreement can be used to argue that a genetic relationship with Altaic is unlikely.

The hypothesis that Korean might be related to Japanese has had some supporters due to some overlap in vocabulary and similar grammatical features that have been elaborated upon by such researchers as Samuel E. Martin and Roy Andrew Miller. Sergei Anatolyevich Starostin (1991) found about 25% of potential cognates in the Japanese–Korean 100-word Swadesh list. Some linguists concerned with the issue, for example Alexander Vovin, have argued that the indicated similarities between Japanese and Korean are not due to any genetic relationship, but rather to a sprachbund effect and heavy borrowing, especially from ancient Korean into Western Old Japanese. A good example might be Middle Korean sàm and Japanese asa, meaning "hemp". This word seems to be a cognate, but although it is well attested in Western Old Japanese and Northern Ryukyuan languages, in Eastern Old Japanese it only occurs in compounds, and it is only present in three dialects of the Southern Ryukyuan language group. Also, the doublet wo meaning "hemp" is attested in Western Old Japanese and Southern Ryukyuan languages. It is thus plausible to assume a borrowed term. (See Classification of the Japonic languages for further details on a possible relationship.)

Among ancient languages, various closer relatives of Korean have been proposed, constituting a possible small Koreanic language family. Some classify the language of Jeju Island as a distinct modern Koreanic language.

Other famous theory is the Dravido-Korean languages theory which suggests a southern relation. Korean and Dravidian languages share similar vocabulary, both languages are agglutinative, follow the SOV order, nominal and adjectives follow the same syntax, particles are post positional, modifiers always precede modified words are some of the common features.

Comparative linguist Kang Gil-un found 1300 Dravidian Tamil cognates in Korean. He mentioned that many of them sound even more similar than own Korean local dialects. He insisted that the Korean language is based on the proto Nivkh language and mingled with lots of Dravidian, Ainu, Tungusic and Turkic vocabulary. The Dravidian cognates in Korean significantly outnumbers that of Tungusic, Turkic or Ainu.

Geographic distribution and international spread

See also: Korean diasporaKorean is spoken by the Korean people in North Korea and South Korea and by the Korean diaspora in many countries including the People's Republic of China, the United States, Japan, and Russia. Korean-speaking minorities exist in these states, but because of cultural assimilation into host countries, not all ethnic Koreans may speak it with native fluency.

Official status

Korean is the official language of South Korea and North Korea. It is also one of the two official languages of the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in China.

In South Korea, the regulatory body for Korean is the Seoul-based National Institute of the Korean Language , which was created by presidential decree on January 23, 1991. In North Korea, the regulatory body is the Language Institute of the Academy of Social Sciences (사회과학원 어학연구소; 社會科學院語學研究所, Sahoe Kwahagwon Ŏhak Yŏnguso).

King Sejong Institute

The King Sejong Institute is a central public institution supporting the King Sejong Institute which is the overseas educational institution of the Korean language and Korean cultures. It was established based on Article 9, Section 2 of the in order to do coordination management of the government's propagation project of the Korean language and Korean cultures.

- Increase in the demand for the Korean language education

- Rapid increase in the Korean language education thanks to the spread of Hanryu, Increase in international marriage, expansion of Korean enterprises' making inroads into overseas markets, and enforcement of employment license system

- Necessity of the National Brand representing the educational institution of the Korean language

- Awareness of necessity of specialized brand cultivation which can do general support of overseas Korean language education based on the successful strategic propagation project of their own language

TOPIK KOREA Institute

TOPIK KOREA Institute is a lifelong educational center affiliated with a variety of Korean universities in Seoul, South Korea, whose aim is to promote Korean language and culture, support local Korean teaching internationally, and facilitate cultural exchanges.

The TOPIK KOREA Institute is sometimes compared to language and culture promotion organizations such as King Sejong Institute. Unlike the organization, however, TOPIK KOREA Institutes operate within established universities and colleges around the world, providing educational materials.

Dialects

Main articles: Korean dialects and Koreanic languages

Korean has numerous small local dialects (called mal (말) , saturi (사투리), or bang'eon (방언 in Korean). The standard language (pyojun-eo or pyojun-mal) of both South Korea and North Korea is based on the dialect of the area around Seoul (which, as Hanyang, was the capital of Joseon-era Korea for 500 years), though the northern standard after the Korean War has been influenced by the dialect of P'yŏngyang. All dialects of Korean are similar to each other and largely mutually intelligible (with the exception of dialect-specific phrases or non-Standard vocabulary unique to dialects), though the dialect of Jeju Island is divergent enough to be sometimes classified as a separate language. One of the more salient differences between dialects is the use of tone: speakers of the Seoul dialect make use of vowel length, whereas speakers of the Gyeongsang dialect maintain the pitch accent of Middle Korean. Some dialects are conservative, maintaining Middle Korean sounds (such as z, β, ə) which have been lost from the standard language, whereas others are highly innovative.

There is substantial evidence for a history of extensive dialect levelling, or even convergent evolution or intermixture of two or more originally distinct linguistic stocks, within the Korean language and its dialects. Many Korean dialects have basic vocabulary that is etymologically distinct from vocabulary of identical meaning in Standard Korean or other dialects, such as South Jeolla dialect /kur/ vs. Standard Korean 입 /ip/ "mouth" or Gyeongsang dialect /t͡ɕʌŋ.ɡu.d͡ʑi/ vs. Standard Korean /puːt͡ɕʰu/ "garlic chives". This suggests that the Korean Peninsula may have at one time been much more linguistically diverse than it is at present. See also the Buyeo languages hypothesis.

Nonetheless, the separation of the two Korean nations has resulted in increasing differences among the dialects that have emerged over time. Since the allies of the newly founded nations split the Korean peninsula in half after 1945, the newly formed Korean nations have since borrowed vocabulary extensively from their respective allies. As the Soviet Union helped industrialize North Korea and establish it as a communist state, the North Koreans would therefore borrow a number of Russian terms. Likewise, since the United States helped South Korea extensively to develop militarily, economically, and politically, South Koreans would therefore borrow extensively from English. The differences among northern and southern dialects have become so significant that many North Korean defectors reportedly have had great difficulty communicating with South Koreans after having initially settled into South Korea. In response to the diverging vocabularies, an app called Univoca was designed to help North Korean defectors learn South Korean terms by translating them into North Korean ones. More info can be found on the page North-South differences in the Korean language.

Aside from the standard language, there are few clear boundaries between Korean dialects, and they are typically partially grouped according to the regions of Korea.

| Standard language | Locations of use |

|---|---|

| Seoul | Seoul (서울); very similar to Incheon (인천/仁川) and most of Gyeonggi (경기/京畿), west of Gangwon-do (Yeongseo region) |

| Munhwaŏ | Northern standard. Based on P'yŏngan dialect. |

| Regional dialects | Locations of use |

| Hamgyŏng (Northeastern) | Rasŏn, most of Hamgyŏng region, northeast P'yŏngan, Ryanggang (North Korea), Jilin (China) |

| P'yŏngan (northwestern) | P'yŏngan region, P'yŏngyang, Chagang, Hwanghae, northern North Hamgyŏng (North Korea), Liaoning (China) |

| Central | Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi, Daejeon, Chungcheong (South Korea), Yeongseo (Gangwon-do (South Korea)/Kangwŏn (North Korea) west of the Taebaek Mountains) |

| Yeongdong (East coast) | Yeongdong region (Gangwon-do (South Korea)/Kangwŏn (North Korea) east of the Taebaek Mountains) |

| Gyeongsang (Southeastern) | Busan, Daegu, Ulsan, Gyeongsang region (South Korea) |

| Jeolla (Southwestern) | Gwangju, Jeolla region (South Korea) |

| Jeju | Jeju Island/Province (South Korea) |

Phonology

This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between , / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. Main article: Korean phonologyConsonants

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | ㅁ /m/ | ㄴ /n/ | ㅇ /ŋ/ | |||

| Plosive and Affricate |

plain | ㅂ /p/ or /b/ | ㄷ /t/ or /d/ | ㅈ /t͡ɕ/ or /d͡ʑ/ | ㄱ /k/ or /g/ | |

| tense | ㅃ /p͈/ | ㄸ /t͈/ | ㅉ /t͡ɕ͈/ | ㄲ /k͈/ | ||

| aspirated | ㅍ /pʰ/ | ㅌ /tʰ/ | ㅊ /t͡ɕʰ/ | ㅋ /kʰ/ | ||

| Fricative | plain | ㅅ /sʰ/ | ㅎ /h/ | |||

| tense | ㅆ /s͈/ | |||||

| Approximant | /w/ | ㄹ /l/ | /j/ | |||

The semivowels /w/ and /j/ are represented in Korean writing by modifications to vowel symbols (see below).

The IPA symbol ⟨◌͈⟩ (a subscript double straight quotation mark, shown here with a placeholder circle) is used to denote the tensed consonants /p͈/, /t͈/, /k͈/, /t͡ɕ͈/, /s͈/. Its official use in the Extensions to the IPA is for 'strong' articulation, but is used in the literature for faucalized voice. The Korean consonants also have elements of stiff voice, but it is not yet known how typical this is of faucalized consonants. They are produced with a partially constricted glottis and additional subglottal pressure in addition to tense vocal tract walls, laryngeal lowering, or other expansion of the larynx.

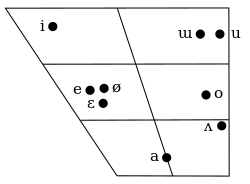

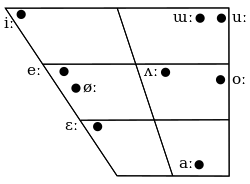

Vowels

|

|

|

| Monophthongs | /i/ ㅣ, /e/ ㅔ, /ɛ/ ㅐ, /a/ ㅏ, /o/ ㅗ, /u/ ㅜ, /ə/ ㅓ, /ɯ/ ㅡ, /ø/ ㅚ |

|---|---|

| Vowels preceded by intermediaries, or diphthongs |

/je/ ㅖ, /jɛ/ ㅒ, /ja/ ㅑ, /wi/ ㅟ, /we/ ㅞ, /wɛ/ ㅙ, /wa/ ㅘ, /ɰi/ ㅢ, /jo/ ㅛ, /ju/ ㅠ, /jə/ ㅕ, /wə/ ㅝ |

^* ㅏ is closer to a near-open central vowel (), though ⟨a⟩ is still used for tradition.

Allophones

/s/ is aspirated and becomes an alveolo-palatal before or for most speakers (but see North–South differences in the Korean language). This occurs with the tense fricative and all the affricates as well. At the end of a syllable, /s/ changes to /t/ (example: beoseot (버섯) 'mushroom').

/h/ may become a bilabial before or , a palatal before or , a velar before , a voiced between voiced sounds, and a elsewhere.

/p, t, t͡ɕ, k/ become voiced between voiced sounds.

/m, n/ frequently denasalize to at the beginnings of words.

/l/ becomes alveolar flap between vowels, and or at the end of a syllable or next to another /l/. Note that a written syllable-final 'ㄹ', when followed by a vowel or a glide (i.e., when the next character starts with 'ㅇ'), migrates to the next syllable and thus becomes .

Traditionally, /l/ was disallowed at the beginning of a word. It disappeared before , and otherwise became /n/. However, the inflow of western loanwords changed the trend, and now word-initial /l/ (mostly from English loanwords) are pronounced as a free variation of either or . The traditional prohibition of word-initial /l/ became a morphological rule called "initial law" (두음법칙) in South Korea, which pertains to Sino-Korean vocabulary. Such words retain their word-initial /l/ in North Korea.

All obstruents (plosives, affricates, fricatives) at the end of a word are pronounced with no audible release, .

Plosive stops /p, t, k/ become nasal stops before nasal stops.

Hangul spelling does not reflect these assimilatory pronunciation rules, but rather maintains the underlying, partly historical morphology. Given this, it is sometimes hard to tell which actual phonemes are present in a certain word.

One difference between the pronunciation standards of North and South Korea is the treatment of initial , and initial . For example,

- "labor" – north: rodong (로동), south: nodong (노동)

- "history" – north: ryŏksa (력사), south: yeoksa (역사)

- "female" – north: nyŏja (녀자), south: yeoja (여자)

Morphophonemics

Main article: MorphophonologyGrammatical morphemes may change shape depending on the preceding sounds. Examples include -eun/-neun (-은/-는) and -i/-ga (-이/-가). Sometimes sounds may be inserted instead. Examples include -eul/-reul (-을/-를), -euro/-ro (-으로/-로), -eseo/-seo (-에서/-서), -ideunji/-deunji (-이든지/-든지) and -iya/-ya (-이야/-야). However, -euro/-ro is somewhat irregular, since it will behave differently after a rieul consonant.

| After a consonant | After a ㄹ (rieul) | After a vowel |

|---|---|---|

| -ui (-의) | ||

| -eun (-은) | -neun (-는) | |

| -i (-이) | -ga (-가) | |

| -eul (-을) | -reul (-를) | |

| -gwa (-과) | -wa (-와) | |

| -euro (-으로) | -ro (-로) | |

Some verbs may also change shape morphophonemically.

Grammar

Main article: Korean grammarKorean is an agglutinative language. The Korean language is traditionally considered to have nine parts of speech. For details, see Korean parts of speech. Modifiers generally precede the modified words, and in the case of verb modifiers, can be serially appended. The basic form of a Korean sentence is subject–object–verb, but the verb is the only required and immovable element.

| A: | 가게에 | 갔어요? | ||

| ga-ge-e | ga-sseo-yo | |||

| store + | ++++ |

- "Did go to the store?" ("you" implied in conversation)

| B: | 예. (or 네.) | |

| ye (or ne, de) | ||

| yes |

- "Yes."

Speech levels and honorifics

Main article: Korean honorificsThe relationship between a speaker or writer and his or her subject and audience is paramount in Korean grammar. The relationship between speaker/writer and subject referent is reflected in honorifics, whereas that between speaker/writer and audience is reflected in speech level.

Honorifics

When talking about someone superior in status, a speaker or writer usually uses special nouns or verb endings to indicate the subject's superiority. Generally, someone is superior in status if he/she is an older relative, a stranger of roughly equal or greater age, or an employer, teacher, customer, or the like. Someone is equal or inferior in status if he/she is a younger stranger, student, employee or the like. Nowadays, there are special endings which can be used on declarative, interrogative, and imperative sentences; and both honorific or normal sentences. They are made for easier and faster use of Korean.

Honorifics in traditional Korea were strictly hierarchical. The caste and estate systems possessed patterns and usages much more complex and stratified than those used today. The intricate structure of the Korean honorific system flourished in traditional culture and society. Honorifics in contemporary Korea are now used for people who are psychologically distant. Honorifics are also used for people who are superior in status. For example, older relatives, people who are older, teachers, and employers.

Speech levels

There are seven verb paradigms or speech levels in Korean, and each level has its own unique set of verb endings which are used to indicate the level of formality of a situation. Unlike honorifics—which are used to show respect towards the referent (the person spoken of) —speech levels are used to show respect towards a speaker's or writer's audience (the person spoken to). The names of the seven levels are derived from the non-honorific imperative form of the verb 하다 (hada, "do") in each level, plus the suffix 체 ("che", hanja: 體), which means "style".

The highest six levels are generally grouped together as jondaenmal (존댓말), whereas the lowest level (haeche, 해체) is called banmal (반말) in Korean.

Nowadays, younger-generation speakers no longer feel obligated to lower their usual regard toward the referent. It is common to see younger people talk to their older relatives with banmal (반말). This is not out of disrespect, but instead it shows the intimacy and the closeness of the relationship between the two speakers. Transformations in social structures and attitudes in today's rapidly changing society have brought about change in the way people speak.

Sociolinguistics

Gender and the Korean language

In general, Korean lacks grammatical gender. As one of the few exceptions, the third-person singular pronoun has two different forms: 그 geu (male) and 그녀 geunyeo (female). However, these terms were invented in the 20th century under the influence of foreign languages, and they seldom appear in colloquial speech.

However, one can still find stronger contrasts between the genders within Korean speech. Some examples of this can be seen in: (1) softer tone used by women in speech; (2) a married woman introducing herself as someone’s mother or wife, not with her own name; (3) the presence of gender differences in titles and occupational terms (for example, a sajang is a company president and yŏsajang is a female company president.); (4) females sometimes using more tag questions and rising tones in statements, also seen in speech from children.

In Western societies, individuals tend to avoid expressions of power asymmetry, mutually addressing each other by their first names for the sake of solidarity . Between two people of asymmetrical status in a Korean society, people tend to emphasize differences in status for the sake of solidarity. Koreans prefer to use kinship terms rather than any other terms of reference. In traditional Korean society, women have long been in disadvantaged positions. Korean social structure traditionally was a patriarchically dominated family system that emphasized the maintenance of family lines. This structure has tended to separate the roles of women from those of men.

Vocabulary

The core of the Korean vocabulary is made up of native Korean words. A significant proportion of the vocabulary, especially words that denote abstract ideas, are Sino-Korean words, either

- directly borrowed from written Chinese, or

- coined in Korea or Japan using Chinese characters,

The exact proportion of Sino-Korean vocabulary is a matter of debate. Sohn (2001) stated 50–60%. Later, the same author (2006, p. 5) gives an even higher estimate of 65%. Jeong Jae-do, one of the compilers of the dictionary Urimal Keun Sajeon, asserts that the proportion is not so high. He points out that Korean dictionaries compiled during the colonial period include many unused Sino-Korean words. In his estimation, the proportion of native Korean vocabulary in the Korean language might be as high as 70%.

Korean has two numeral systems: one native, and one borrowed from Sino-Korean.

To a much lesser extent, some words have also been borrowed from Mongolian and other languages. Conversely, the Korean language itself has also contributed some loanwords to other languages, most notably the Tsushima dialect of Japanese.

The vast majority of loanwords other than Sino-Korean come from modern times, approximately 90% of which are from English. Many words have also been borrowed from Western languages such as German via Japanese (아르바이트 (areubaiteu) "part-time job", 알레르기 (allereugi) "allergy", 기브스 (gibseu or gibuseu) "plaster cast used for broken bones"). Some Western words were borrowed indirectly via Japanese during the Japanese occupation of Korea, taking a Japanese sound pattern, for example "dozen" > ダース dāsu > 다스 daseu. Most indirect Western borrowings are now written according to current "Hangulization" rules for the respective Western language, as if borrowed directly. There are a few more complicated borrowings such as "German(y)" (see names of Germany), the first part of whose endonym the Japanese approximated using the kanji 獨逸 doitsu that were then accepted into the Korean language by their Sino-Korean pronunciation: 獨 dok + 逸 il = Dogil. In South Korean official use, a number of other Sino-Korean country names have been replaced with phonetically oriented "Hangeulizations" of the countries' endonyms or English names.

Because of such a prevalence of English in modern Korean culture and society, lexical borrowing is inevitable. English-derived Korean, or 'Konglish' (콩글리쉬), is increasingly used. The vocabulary of the Korean language is roughly 5% loanwords (excluding Sino-Korean vocabulary).

Korean uses words adapted from English in ways that may seem strange to native English speakers. For example, in soccer heading (헤딩) is used as a noun meaning a 'header', whereas fighting (화이팅 / 파이팅) is a term of encouragement like 'come on'/'go (on)' in English. Something that is 'service' (서비스) is free or 'on the house'. A building referred to as an 'apart-uh' (아파트) is an 'apartment' (but in fact refers to a residence more akin to a condominium) and a type of pencil that is called a 'sharp' (샤프) is a mechanical pencil.

North Korean vocabulary shows a tendency to prefer native Korean over Sino-Korean or foreign borrowings, especially with recent political objectives aimed at eliminating foreign influences on the Korean language in the North. In the early years, the North Korean government tried to eliminate Sino-Korean words. Consequently, South Korean may have several Sino-Korean or foreign borrowings which are not in North Korean.

Writing system

|

| Korean writing systems |

|---|

| Hangul |

|

| Hanja |

| Mixed script |

| Braille |

| Transcription |

|

| Transliteration |

|

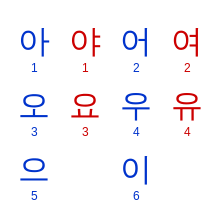

Before the creation of Hangul, people in Korea (known as Joseon at the time) primarily wrote using Classical Chinese alongside native phonetic writing systems that predate Hangul by hundreds of years, including idu, hyangchal, gugyeol, and gakpil. However, due to the fundamental differences between the Korean and Chinese languages, and the large number of characters needed to be learned, there was much difficulty in learning how to write using Chinese characters for the lower classes, who often didn't have the privilege of education. To assuage this problem, King Sejong created the unique alphabet known as Hangul to promote literacy among the common people.

Hangul was denounced and looked down upon by the yangban aristocracy who deemed it too easy to learn, but it gained widespread use among the common class, and was widely used to print popular novels which were enjoyed by the common class. With growing Korean nationalism in the 19th century, the Gabo Reformists' push, and the promotion of Hangul in schools, in 1894, Hangul displaced hanja as Korea's national script. Hanja is still used to a certain extent in South Korea where it is sometimes combined with Hangul, but this method is slowly declining in use despite students learning hanja in school.

Below is a chart of the Korean alphabet's symbols and their canonical IPA values:

| Hangul 한글 | ㅂ | ㄷ | ㅈ | ㄱ | ㅃ | ㄸ | ㅉ | ㄲ | ㅍ | ㅌ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅅ | ㅎ | ㅆ | ㅁ | ㄴ | ㅇ | ㄹ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | b | d | j | g | pp | tt | jj | kk | p | t | ch | k | s | h | ss | m | n | ng | r, l |

| IPA | p | t | t͡ɕ | k | p͈ | t͈ | t͡ɕ͈ | k͈ | pʰ | tʰ | t͡ɕʰ | kʰ | s | h | s͈ | m | n | ŋ | ɾ, l |

| Hangul 한글 | ㅣ | ㅔ | ㅚ | ㅐ | ㅏ | ㅗ | ㅜ | ㅓ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅖ | ㅒ | ㅑ | ㅛ | ㅠ | ㅕ | ㅟ | ㅞ | ㅙ | ㅘ | ㅝ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | i | e | oe | ae | a | o | u | eo | eu | ui | ye | yae | ya | yo | yu | yeo | wi | we | wae | wa | wo |

| IPA | i | e | ø, we | ɛ | a | o | u | ʌ | ɯ | ɰi | je | jɛ | ja | jo | ju | jʌ | ɥi, wi | we | wɛ | wa | wʌ |

Modern Korean is written with spaces between words, a feature not found in Chinese or Japanese. Korean punctuation marks are almost identical to Western ones. Traditionally, Korean was written in columns, from top to bottom, right to left, but is now usually written in rows, from left to right, top to bottom.

Differences between North Korean and South Korean

Main article: North–South differences in the Korean languageThe Korean language used in the North and the South exhibits differences in pronunciation, spelling, grammar and vocabulary.

Pronunciation

In North Korea, palatalization of /si/ is optional, and /t͡ɕ/ can be pronounced between vowels.

Words that are written the same way may be pronounced differently, such as the examples below. The pronunciations below are given in Revised Romanization, McCune–Reischauer and Hangul, the last of which represents what the Hangul would be if one were to write the word as pronounced.

| Word | Meaning | Pronunciation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North (RR/MR) | North (Hangul) | South (RR/MR) | South (Hangul) | ||

| 읽고 | to read (continuative form) |

ilko (ilko) | 일코 | ilkko (ilkko) | 일꼬 |

| 압록강 | Amnok River | amrokgang (amrokkang) | 암록깡 | amnokkang (amnokkang) | 암녹깡 |

| 독립 | independence | dongrip (tongrip) | 동립 | dongnip (tongnip) | 동닙 |

| 관념 | idea / sense / conception | gwallyeom (kwallyŏm) | 괄렴 | gwannyeom (kwannyŏm) | 관념 |

| 혁신적* | innovative | hyeoksinjjeok (hyŏksintchŏk) | 혁씬쩍 | hyeoksinjeok (hyŏksinjŏk) | 혁씬적 |

* Similar pronunciation is used in the North whenever the hanja "的" is attached to a Sino-Korean word ending in ㄴ, ㅁ or ㅇ. (In the South, this rule only applies when it is attached to any single-character Sino-Korean word.)

Spelling

Some words are spelled differently by the North and the South, but the pronunciations are the same.

| Word | Meaning | Pronunciation (RR/MR) | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North spelling | South spelling | |||

| 해빛 | 햇빛 | sunshine | haeppit (haepit) | The "sai siot" ('ㅅ' used for indicating sound change) is almost never written out in the North. |

| 벗꽃 | 벚꽃 | cherry blossom | beotkkot (pŏtkkot) | |

| 못읽다 | 못 읽다 | cannot read | modikda (modikta) | Spacing. |

| 한나산 | 한라산 | Hallasan | hallasan (hallasan) | When a ㄴㄴ combination is pronounced as ll, the original Hangul spelling is kept in the North, whereas the Hangul is changed in the South. |

| 규률 | 규율 | rules | gyuyul (kyuyul) | In words where the original hanja is spelt "렬" or "률" and follows a vowel, the initial ㄹ is not pronounced in the North, making the pronunciation identical with that in the South where the ㄹ is dropped in the spelling. |

Spelling and pronunciation

Some words have different spellings and pronunciations in the North and the South, some of which were given in the "Phonology" section above:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North spelling | North pronun. | South spelling | South pronun. | ||

| 력량 | ryeongryang (ryŏngryang) | 역량 | yeongnyang (yŏngnyang) | strength | Initial r's are dropped if followed by i or y in the South Korean version of Korean. |

| 로동 | rodong (rodong) | 노동 | nodong (nodong) | work | Initial r's are demoted to an n if not followed by i or y in the South Korean version of Korean. |

| 원쑤 | wonssu (wŏnssu) | 원수 | wonsu (wŏnsu) | mortal enemy | "Mortal enemy" and "field marshal" are homophones in the South. Possibly to avoid referring to Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il or Kim Jong-un as the enemy, the second syllable of "enemy" is written and pronounced 쑤 in the North. |

| 라지오 | rajio (rajio) | 라디오 | radio (radio) | radio | |

| 우 | u (u) | 위 | wi (wi) | on; above | |

| 안해 | anhae (anhae) | 아내 | anae (anae) | wife | |

| 꾸바 | kkuba (kkuba) | 쿠바 | kuba (k'uba) | Cuba | When transcribing foreign words from languages that do not have contrasts between aspirated and unaspirated stops, North Koreans generally use tensed stops for the unaspirated ones while South Koreans use aspirated stops in both cases. |

| 페 | pe (p'e) | 폐 | pye (p'ye), pe (p'e) | lungs | In the case where ye comes after a consonant, such as in hye and pye, it is pronounced without the palatal approximate. North Korean orthography reflect this pronunciation nuance. |

In general, when transcribing place names, North Korea tends to use the pronunciation in the original language more than South Korea, which often uses the pronunciation in English. For example:

| Original name | North Korea transliteration | English name | South Korea transliteration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spelling | Pronunciation | Spelling | Pronunciation | ||

| Ulaanbaatar | 울란바따르 | ullanbattareu (ullanbattarŭ) | Ulan Bator | 울란바토르 | ullanbatoreu (ullanbat'orŭ) |

| København | 쾨뻰하븐 | koeppenhabeun (k'oeppenhabŭn) | Copenhagen | 코펜하겐 | kopenhagen (k'op'enhagen) |

| al-Qāhirah | 까히라 | kkahira (kkahira) | Cairo | 카이로 | kairo (k'airo) |

Grammar

Some grammatical constructions are also different:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North spelling | North pronun. | South spelling | South pronun. | ||

| 되였다 | doeyeotda (toeyŏtta) | 되었다 | doeeotda (toeŏtta) | past tense of 되다 (doeda/toeda), "to become" | All similar grammar forms of verbs or adjectives that end in ㅣ in the stem (i.e. ㅣ, ㅐ, ㅔ, ㅚ, ㅟ and ㅢ) in the North use 여 instead of the South's 어. |

| 고마와요 | gomawayo (komawayo) | 고마워요 | gomawoyo (komawŏyo) | thanks | ㅂ-irregular verbs in the North use 와 (wa) for all those with a positive ending vowel; this only happens in the South if the verb stem has only one syllable. |

| 할가요 | halgayo (halkayo) | 할까요 | halkkayo (halkkayo) | Shall we do? | Although the Hangul differ, the pronunciations are the same (i.e. with the tensed ㄲ sound). |

Vocabulary

Some vocabulary is different between the North and the South:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North word | North pronun. | South word | South pronun. | ||

| 문화주택 | munhwajutaek (munhwajut'aek) | 아파트 | apateu (ap'at'ŭ) | Apartment | 아빠트 (appateu/appat'ŭ) is also used in the North. |

| 조선말 | joseonmal (josŏnmal) | 한국말 | han-gukmal (han'gukmal) | Korean language | |

| 곽밥 | gwakbap (kwakpap) | 도시락 | dosirak (tosirak) | lunch box | |

| 동무 | dongmu (tongmu) | 친구 | chin-gu (ch'in-gu) | Friend | 동무 was originally a non-ideological word for "friend" used all over the Korean peninsula, but North Koreans later adopted it as the equivalent of the Communist term of address "comrade". As a result, to South Koreans today the word has a heavy political tinge, and so they have shifted to using other words for friend like chingu (친구) or beot (벗). |

Punctuation

In the North, guillemets 《 and 》 are the symbols used for quotes; in the South, quotation marks equivalent to the English ones, “ and ”, are standard, although 『 』 and 「 」 are also used.

Study by non-native learners

For native English speakers, Korean is generally considered to be one of the most difficult languages to master despite the relative ease of learning Hangul. For instance, the United States' Defense Language Institute places Korean in Category IV, which also includes Japanese, Chinese (e.g. Mandarin, Cantonese & Shanghainese) and Arabic. This means that 63 weeks of instruction (as compared to just 25 weeks for Italian, French, Portuguese and Spanish) are required to bring an English-speaking student to a limited working level of proficiency in which he or she has "sufficient capability to meet routine social demands and limited job requirements" and "can deal with concrete topics in past, present, and future tense." Similarly, the Foreign Service Institute's School of Language Studies places Korean in Category IV, the highest level of difficulty.

The study of the Korean language in the United States is dominated by Korean American heritage language students; in 2007 they were estimated to form over 80% of all students of the language at non-military universities. However, Sejong Institutes in the United States have noted a sharp rise in the number of people of other ethnic backgrounds studying Korean between 2009 and 2011; they attribute this to rising popularity of South Korean music and television shows.

There are two widely used tests of Korean as a foreign language: the Korean Language Proficiency Test (KLPT) and the Test of Proficiency in Korean (TOPIK). The Korean Language Proficiency Test, an examination aimed at assessing non-native speakers' competence in Korean, was instituted in 1997; 17,000 people applied for the 2005 sitting of the examination. The TOPIK was first administered in 1997 and was taken by 2,274 people. Since then the total number of people who have taken the TOPIK has surpassed 1 million, with more than 150,000 candidates taking the test in 2012.

See also

- Hangul

- Korean count word

- Korean Cultural Center (KCC)

- Korean language and computers

- Korean mixed script

- Korean numerals

- Korean particles

- Korean phonology

- Korean romanization

- Korean Wave

- Koreanic languages

- Language isolate

- Dravido-Korean languages

- Hanja (Classical Chinese characters in Korean)

- List of English words of Korean origin

- List of Korea-related topics

- Sino-Korean vocabulary

- Vowel harmony

References

- Korean language at Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013) [REDACTED]

- Summary by language size, table 3.

- Song, Jae Jung (2005), The Korean language: structure, use and context, Routledge, p. 15, ISBN 9780415328029.

- Campbell, Lyle; Mixco, Mauricio (2007), "Korean, A language isolate", A Glossary of Historical Linguistics, University of Utah Press, pp. 7, 90–91,

most specialists... no longer believe that the... Altaic groups... are related Korean is often said to belong with the Altaic hypothesis, often also with Japanese, though this is not widely supported

. - Dalby, David (1999–2000), The Register of the World's Languages and Speech Communities, Linguasphere Press.

- Kim, Nam-Kil (1992), "Korean", International Encyclopedia of Linguistics, vol. 2, pp. 282–86,

scholars have tried to establish genetic relationships between Korean and other languages and major language families, but with little success

. - Róna-Tas, András (1998), "The Reconstruction of Proto-Turkic and the Genetic Question", The Turkic Languages, Routledge, pp. 67–80,

have been heavily criticised in more recent studies, though the idea of a genetic relationship has not been totally abandoned

. - Schönig, Claus (2003), "Turko-Mongolic Relations", The Mongolic Languages, Routledge, pp. 403–19,

the 'Altaic' languages do not seem to share a common basic vocabulary of the type normally present in cases of genetic relationship

. - Sanchez-Mazas; Blench; Ross; Lin; Pejros, eds. (2008), "Stratification in the peopling of China: how far does the linguistic evidence match genetics and archaeology?", Human migrations in continental East Asia and Taiwan: genetic, linguistic and archaeological evidence, Taylor & Francis

- Andrew Logie. "Are Korean and Japanese related? The Altaic hypothesis continued." Koreanology. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- "Google Ngram Viewer".

- Miller 1971, 1996, Starostin et al. 2003

- Vovin 2008: 1

- Trask 1996: 147–51

- Rybatzki 2003: 57

- Vovin 2008: 5

- Martin 1966, 1990

- e.g. Miller 1971, 1996

- Starostin, Sergei (1991). Altaiskaya problema i proishozhdeniye yaponskogo yazika (PDF). Moscow: Nauka.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Vovin 2008

- Whitman 1985: 232, also found in Martin 1966: 233

- Vovin 2008: 211–12

- "The Korean Language". Cambridge University Press. P. 29. Min–Sohn, Ho (2001). The Korean Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|min-sohn, ho (2001). the korean language. cambridge university press. p. 29.=(help) - Kang, Gil-un (1990). 고대사의 비교언어학적 연구. 새문사.

- Source: Unescopress. "New interactive atlas adds two more endangered languages | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". Unesco.org. Retrieved 2013-12-11.

- David Lightfoot, 1999. The development of language: acquisition, change, and evolution

- Janhunen, Juha, 1996. Manchuria: an ethnic history

- "Korean is virtually two languages, and that's a big problem for North Korean defectors". Public Radio International. Retrieved 2016-01-18.

- Lee & Ramsey, 2000. The Korean language

- only at the end of a syllable

- ^ Sohn, Ho-Min (2006). Korean Language in Culture and Society. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8248-2694-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Choo, Miho (2008). Using Korean: A Guide to Contemporary Usage. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 1139471392.

- Cho, Young A. Gender Differences in Korean Speech. Korean Language in Culture and Society. Ed. Ho-min Sohn. University of Hawaii Press, 2006. pp. 189–98.

- Kim, Minju. “Cross Adoption of language between different genders: The case of the Korean kinship terms hyeng and enni.” Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Women and Language Conference. Berkeley: Berkeley Women and Language Group. 1999.

- Palley, Marian Lief. “Women’s Status in South Korea: Tradition and Change.” Asian Survey, Vol 30 No. 12. December 1990. pp. 1136–53.

- ^ Sohn, Ho-Min. The Korean Language (Section 1.5.3 "Korean vocabulary", pp. 12–13), Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-521-36943-6.

- Kim, Jin-su (2009-09-11). "우리말 70%가 한자말? 일제가 왜곡한 거라네/Our language is 70% hanja? Japanese Empire distortion". The Hankyoreh. Retrieved 2009-09-11.. The dictionary mentioned is "우리말 큰 사전". Seoul: Hangul Hakhoe. 1992. OCLC 27072560.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hannas, Wm C. Asia's Orthographic Dilemma. University of Hawaii Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780824818920. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- Chen, Jiangping. Multilingual Access and Services for Digital Collections. ABC-CLIO. p. 66. ISBN 9781440839559. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- "Invest Korea Journal". 23. Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency. 1 January 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

They later devised three different systems for writing Korean with Chinese characters: Hyangchal, Gukyeol and Idu. These systems were similar to those developed later in Japan and were probably used as models by the Japanese.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Korea Now". 29. Korea Herald. 1 July 2000. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Koerner, E. F. K.; Asher, R. E. Concise History of the Language Sciences: From the Sumerians to the Cognitivists. Elsevier. p. 54. ISBN 9781483297545. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Montgomery, Charles (19 January 2016). "Korean Literature in Translation – CHAPTER FOUR: IT ALL CHANGES! THE CREATION OF HANGUL". www.ktlit.com. KTLit. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

Hangul was sometimes known as the "language of the inner rooms," (a dismissive term used partly by yangban in an effort to marginalize the alphabet), or the domain of women.

- Chan, Tak-hung Leo. One Into Many: Translation and the Dissemination of Classical Chinese Literature. Rodopi. p. 183. ISBN 9042008156. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- "Korea News Review". Korea Herald, Incorporated. 1 January 1994. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Lee, Kenneth B. Korea and East Asia: The Story of a Phoenix. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 90. ISBN 9780275958237. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Silva, David J. (2008). "Missionary Contributions toward the Revaluation of Han'geul in Late 19th Century Korea". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 192: 57–74. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2008.035.

- "Korean History". Korea.assembly.go.kr. Retrieved 2016-04-26.

Korean Empire, Edict of No. 1 - All official documents are to be written in Hangul, and not Chinese characters.

- "현판 글씨들이 한글이 아니라 한자인 이유는?". royalpalace.go.kr. Retrieved 2016-04-26.

- Kanno, Hiroomi (ed.) / Society for Korean Linguistics in Japan (1987). Chōsengo o manabō (『朝鮮語を学ぼう』), Sanshūsha, Tokyo. ISBN 4-384-01506-2

- Sohn 2006, p. 38 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSohn2006 (help)

- Choe, Sang-hun (2006-08-30). "Koreas: Divided by a common language". Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- "Beliefs that bind". Korea JoongAng Daily. 2007-10-23. Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- Raugh, Harold E. "The Origins of the Transformation of the Defense Language Program" (PDF). Applied Language Learning. 16 (2): 1–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Languages". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- Lee, Saekyun H.; HyunJoo Han. "Issues of Validity of SAT Subject Test Korea with Listening" (PDF). Applied Language Learning. 17 (1): 33–56. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-25.

- "Global popularity of Korean language surges". Korea Herald. 2012-07-22. Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- "Korea Marks 558th Hangul Day". The Chosun Ilbo. 2004-10-10. Archived from the original on 2008-02-19. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- "Korean language test-takers pass 1 mil". The Korea Times. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)

Further reading

- Argüelles, Alexander, and Jong-Rok Kim (2000). A Historical, Literary and Cultural Approach to the Korean Language. Seoul: Hollym.

- Argüelles, Alexander, and Jongrok Kim (2004). A Handbook of Korean Verbal Conjugation. Hyattsville, Maryland: Dunwoody Press.

- Arguelles, Alexander (2007). Korean Newspaper Reader. Hyattsville, Maryland: Dunwoody Press.

- Arguelles, Alexander (2010). North Korean Reader. Hyattsville, Maryland: Dunwoody Press

- Chang, Suk-jin (1996). Korean. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 1-55619-728-4. (Volume 4 of the London Oriental and African Language Library).

- Hulbert, Homer B. (1905). A Comparative Grammar of the Korean Language and the Dravidian Dialects in India. Seoul.

- Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011). A History of the Korean Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66189-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Martin, Samuel E. (1966). Lexical Evidence Relating Japanese to Korean. Language 42/2: 185–251.

- Martin, Samuel E. (1990). Morphological clues to the relationship of Japanese and Korean. In: Philip Baldi (ed.): Linguistic Change and Reconstruction Methodology. Trends in Linguistics: Studies and Monographs 45: 483–509.

- Martin, Samuel E. (2006). A Reference Grammar of Korean: A Complete Guide to the Grammar and History of the Korean Language – 韓國語文法總監. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-804-83771-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miller, Roy Andrew (1971). Japanese and the Other Altaic Languages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-52719-0.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (1996). Languages and History: Japanese, Korean and Altaic. Oslo: Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture. ISBN 974-8299-69-4.

- Ramstedt, G. J. (1928). Remarks on the Korean language. Mémoires de la Société Finno-Oigrienne 58.

- Rybatzki, Volker (2003). Middle Mongol. In: Juha Janhunen (ed.) (2003): The Mongolic languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1133-3, pp. 47–82.

- Starostin, Sergei A., Anna V. Dybo, and Oleg A. Mudrak (2003). Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages, 3 volumes. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13153-1.

- Sohn, H.-M. (1999). The Korean Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sohn, Ho-Min (2006). Korean Language in Culture and Society. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8248-2694-9.

- Song, J.-J. (2005). The Korean Language: Structure, Use and Context. London: Routledge.

- Trask, R. L. (1996). Historical linguistics. Hodder Arnold.

- Vovin, Alexander (2010). Koreo-Japonica: A Re-evaluation of a Common Genetic Origin. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- Whitman, John B. (1985). The Phonological Basis for the Comparison of Japanese and Korean. Unpublished Harvard University Ph.D. dissertation.

External links

- Linguistic and Philosophical Origins of the Korean Alphabet (Hangul)

- Sogang University free online Korean language and culture course

- Beginner's guide to Korean for English speakers

- USA Foreign Service Institute Korean basic course

- Linguistic map of Korea

- dongsa.net, Korean verb conjugation tool

- Korean Swadesh vocabulary list at Wiktionary

- Hanja Explorer, a tool to visualize and study Korean vocabulary

- Template:Dmoz

| Korean language | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History |

|  | ||||||||||

| Standard |

| |||||||||||

| Dialects |

| |||||||||||

| Koreanic languages | ||||||||||||

| Writing system |

| |||||||||||

| Grammar | ||||||||||||

| Literature | ||||||||||||

| Other topics | ||||||||||||

- Korean writing system

- Languages attested from the 4th century

- Korean language

- Agglutinative languages

- Buyeo languages

- Languages of Korea

- Languages of South Korea

- Languages of North Korea

- Languages of China

- Languages of Japan

- Languages of Canada

- Languages of the United States

- National symbols of Korea

- Subject–object–verb languages