| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Alodorm, Apodorm, Arem, Cerson, Insoma, Insomin, Mogadon, Nitrados, Nitrazadon, Nitrosun, Nitravet, Ormodon, Paxadorm, Remnos, Epam, and Somnite |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Dependence liability | Physical: High Psychological: Moderate |

| Addiction liability | Moderate |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 53–94% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 16–38 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.151 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H11N3O3 |

| Molar mass | 281.271 g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (what is this?) (verify) | |

Nitrazepam, sold under the brand name Mogadon among others, is a hypnotic drug of the benzodiazepine class used for short-term relief from severe, disabling anxiety and insomnia. It also has sedative (calming) properties, as well as amnestic (inducing forgetfulness), anticonvulsant, and skeletal muscle relaxant effects.

It was first synthesized in the late 1950s by a team of researchers at Hoffmann-La Roche in Switzerland. It was patented in 1961 and came into medical use in 1965.

Medical use

Nitrazepam is used to treat short-term sleeping problems (insomnia), namely difficulty falling asleep, frequent awakening, early awakening, or a combination of each.

Nitrazepam is sometimes tried to treat epilepsy when other medications fail. It has been found to be more effective than clonazepam in the treatment of West syndrome, which is an age-dependent epilepsy, affecting the very young. In uncontrolled studies, nitrazepam has shown effectiveness in infantile spasms and is sometimes considered when other anti-seizure drugs have failed. However, drowsiness, hypotonia, and most significantly tolerance to anti-seizure effects typically develop with long-term treatment, generally limiting Nitrazepam to acute seizure management.

A light-activated derivative of nitrazepam (fulgazepam) has been developed for research purposes.

Side effects

More common

More common side effects may include: central nervous system depression, including somnolence, dizziness, depressed mood, fatigue, ataxia, headache, vertigo, impairment of memory, impairment of motor functions, a "hungover" feeling in the morning, slurred speech, decreased physical performance, numbed emotions, reduced alertness, muscle weakness, double vision, and inattention have been reported. Unpleasant dreams and rebound insomnia have also been reported.

Nitrazepam is a long-acting benzodiazepine with an elimination half-life of 15–38 hours (mean elimination half-life 26 hours). Residual "hangover" effects after nighttime administration of nitrazepam such as sleepiness, impaired psychomotor and cognitive functions may persist into the next day, which may impair the ability of users to drive safely and increases the risk of falls and hip fractures.

Less common

Less common side effects may include: Hypotension, faintness, palpitation, rash or pruritus, gastrointestinal disturbances, and changes in libido are less common. Very infrequently, paradoxical reactions may occur, for example, excitement, stimulation, hallucinations, hyperactivity, and insomnia. Also, depressed or increased dreaming, disorientation, severe sedation, retrograde amnesia, headache, hypothermia, and delirium tremens are reported. Severe liver toxicity has also been reported.

Cancer

Benzodiazepine use is associated with an increased risk of developing cancer. However, conflicting evidence implies that further research is needed in order to conclude that products of this class really do induce cancer.

Mortality

Nitrazepam therapy, compared with other drug therapies, increases risk of death when used for intractable epilepsy in an analysis of 302 patients. The risk of death from nitrazepam therapy may be greater in younger patients (children below 3.4 years in the study) with intractable epilepsy. In older children (above 3.4 years), the tendency appears to be reversed in this study. Nitrazepam may cause sudden death in children. It can cause swallowing incoordination, high-peaked esophageal peristalsis, bronchospasm, delayed cricopharyngeal relaxation, and severe respiratory distress necessitating ventilatory support in children. Nitrazepam may promote the development of parasympathetic overactivity or vagotonia, leading to potentially fatal respiratory distress in children.

Liver

Nitrazepam has been associated with severe hepatic disorders, similar to other nitrobenzodiazepines. Nitrobenzodiazepines such as nitrazepam, nimetazepam, flunitrazepam, and clonazepam are more toxic to the liver than other benzodiazepines as they are metabolically activated by CYP3A4 which can result in cytotoxicity. This activation can lead to the generation of free radicals and oxidation of thiol, as well as covalent binding with endogenous macromolecules; this results, then, in oxidation of cellular components or inhibition of normal cellular function. Metabolism of a nontoxic drug to reactive metabolites has been causally connected with a variety of adverse reactions.

Other long-term effects

Main article: Long-term effects of benzodiazepinesLong-term use of nitrazepam may carry mental and physical health risks, such as the development of cognitive deficits. These adverse effects show improvement after a period of abstinence. Some other sources however seem to indicate that there is no relation between the use of benzodiazepine medication and dementia. Further research is needed in order to assert that this class of medication does really induce cognitive decline.

Abuse potential

See also: Benzodiazepine drug misuseRecreational use of nitrazepam is common.

A monograph for the drug says: "Treatment with nitrazepam should usually not exceed seven to ten consecutive days. Use for more than two to three consecutive weeks requires complete re-evaluation of the patient. Prescriptions for nitrazepam should be written for short-term use (seven to ten days) and it should not be prescribed in quantities exceeding a one-month supply. Dependence can occur in as little as four weeks."

Tolerance

Tolerance to nitrazepam's effects often appears with regular use. Increased levels of GABA in cerebral tissue and alterations in the activity state of the serotoninergic system occur as a result of nitrazepam tolerance. Tolerance to the sleep-inducing effects of nitrazepam can occur after about seven days; tolerance also frequently occurs to its anticonvulsant effects.

However, other sources indicate that continuous use does not necessarily lead to reduced effectiveness, which implies that tolerance is not automatic and that not all patients exhibit tolerance to the same extent.

Dependence and withdrawal

See also: Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndromeNitrazepam can cause dependence, addiction, and benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Withdrawal from nitrazepam may lead to withdrawal symptoms which are similar to those seen with alcohol and barbiturates. Common withdrawal symptoms include anxiety, insomnia, concentration problems, and fatigue. Discontinuation of nitrazepam produced rebound insomnia after short-term single nightly dose therapy.

Special precautions

Benzodiazepines require special precautions if used in alcohol- or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Caution should be exercised in prescribing nitrazepam to anyone who is of working age due to the significant impairment of psychomotor skills; this impairment is greater when the higher dosages are prescribed.

Nitrazepam in doses of 5 mg or more causes significant deterioration in vigilance performance combined with increased feelings of sleepiness. Nitrazepam at doses of 5 mg or higher impairs driving skills and like other hypnotic drugs, it is associated with an increased risk of traffic accidents. In the elderly, nitrazepam is associated with an increased risk of falls and hip fractures due to impairments of body balance. The elimination half-life of nitrazepam is 40 hours in the elderly and 29 hours in younger adults. Nitrazepam is commonly taken in overdose by drug abusers or suicidal individuals, sometimes leading to death. Nitrazepam is teratogenic if taken in overdose during pregnancy with 30% of births showing congenital abnormalities. It is a popular drug of abuse in countries where it is available.

Doses as low as 5 mg can impair driving skills. Therefore, people driving or conducting activities which require vigilance should exercise caution in using nitrazepam or possibly avoid it altogether.

Elderly

Nitrazepam, similar to other benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines, causes impairments in body balance and standing steadiness in individuals who wake up at night or the next morning. Falls and hip fractures are frequently reported. Combination with alcohol increases these impairments. Partial but incomplete tolerance develops to these impairments. Nitrazepam has been found to be dangerous in elderly patients due to a significantly increased risk of falls. This increased risk is probably due to the drug effects of nitrazepam persisting well into the next day. Nitrazepam is a particularly unsuitable hypnotic for the elderly as it induces a disability characterised by general mental deterioration, inability to walk, incontinence, dysarthria, confusion, stumbling, falls, and disoriention which can occur from doses as low as 5 mg. The nitrazepam-induced symptomatology can lead to a misdiagnosis of brain disease in the elderly, for example dementia, and can also lead to the symptoms of postural hypotension which may also be misdiagnosed. A geriatric unit reportedly was seeing as many as seven patients a month with nitrazepam-induced disabilities and health problems. The drug was recommended to join the barbiturates in not being prescribed to the elderly. Only nitrazepam and lorazepam were found to increase the risk of falls and fractures in the elderly. CNS depression occurs much more frequently in the elderly and is especially common in doses above 5 mg of nitrazepam. Both young and old patients report sleeping better after three nights' use of nitrazepam, but they also reported feeling less awake and were slower on psychomotor testing up to 36 hours after intake of nitrazepam. The elderly showed cognitive deficits, making significantly more mistakes in psychomotor testing than younger patients despite similar plasma levels of the drug, suggesting the elderly are more sensitive to nitrazepam due to increased sensitivity of the aging brain to it. Confusion and disorientation can result from chronic nitrazepam administration to elderly subjects. Also, the effects of a single dose of nitrazepam may last up to 60 hours after administration.

Children

Nitrazepam is not recommended for use in those under 18 years of age. Use in very young children may be especially dangerous. Children treated with nitrazepam for epilepsies may develop tolerance within months of continued use, with dose escalation often occurring with prolonged use. Sleepiness, deterioration in motor skills and ataxia were common side effects in children with tuberous sclerosis treated with nitrazepam. The side effects of nitrazepam may impair the development of motor and cognitive skills in children treated with nitrazepam. Withdrawal only occasionally resulted in a return of seizures and some children withdrawn from nitrazepam appeared to improve. Development, for example the ability to walk at five years of age, was impaired in many children taking nitrazepam, but was not impaired with several other nonbenzodiazepine antiepileptic agents. Children being treated with nitrazepam have been recommended to be reviewed and have their nitrazepam gradually discontinued whenever appropriate. Excess sedation, hypersalivation, swallowing difficulty, and high incidence of aspiration pneumonia, as well as several deaths, have been associated with nitrazepam therapy in children.

Pregnancy

Nitrazepam is not recommended during pregnancy as it is associated with causing a neonatal withdrawal syndrome and is not generally recommended in alcohol- or drug-dependent individuals or people with comorbid psychiatric disorders. The Dutch, British and French system called the System of Objectified Judgement Analysis for assessing whether drugs should be included in drug formularies based on clinical efficacy, adverse effects, pharmacokinetic properties, toxicity, and drug interactions was used to assess nitrazepam. A Dutch analysis using the system found nitrazepam to be unsuitable in drug-prescribing formularies.

The use of nitrazepam during pregnancy can lead to intoxication of the newborn. A neonatal withdrawal syndrome can also occur if nitrazepam or other benzodiazepines are used during pregnancy with symptoms such as hyperexcitability, tremor, and gastrointestinal upset (diarrhea or vomiting) occurring. Breast feeding by mothers using nitrazepam is not recommended. Nitrazepam is a long-acting benzodiazepine with a risk of drug accumulation, though no active metabolites are formed during metabolism. Accumulation can occur in various body organs, including the heart; accumulation is even greater in babies. Nitrazepam rapidly crosses the placenta and is present in breast milk in high quantities. Therefore, benzodiazepines including nitrazepam should be avoided during pregnancy. In early pregnancy, nitrazepam levels are lower in the baby than in the mother, and in the later stages of pregnancy, nitrazepam is found in equal levels in both the mother and the unborn child. Internationally benzodiazepines are known to cause harm when used during pregnancy and nitrazepam is a category D drug during pregnancy.

Benzodiazepines are lipophilic and rapidly penetrate membranes, so rapidly penetrate the placenta with significant uptake of the drug. Use of benzodiazepines such as nitrazepam in late pregnancy in especially high doses may result in floppy infant syndrome. Use in the third trimester of pregnancy may result in the development of a severe benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome in the neonate. Withdrawal symptoms from benzodiazepines in the neonate may include hypotonia, and reluctance to suckle, to apnoeic spells, cyanosis, and impaired metabolic responses to cold stress. These symptoms may persist for hours or months after birth.

Other precautions

Caution in hypotension

Caution in those suffering from hypotension, nitrazepam may worsen hypotension.

Caution in hypothyroidism

Caution should be exercised by people who have hypothyroidism, as this condition may cause a long delay in the metabolism of nitrazepam leading to significant drug accumulation.

Contraindications

Nitrazepam should be avoided in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), especially during acute exacerbations of COPD, because serious respiratory depression may occur in patients receiving hypnotics.

As with other hypnotic drugs, nitrazepam is associated with an increased risk of traffic accidents. Nitrazepam is recommended to be avoided in patients who drive or operate machinery. A study assessing driving skills of sedative hypnotic users found the users of nitrazepam to be significantly impaired up to 17 hours after dosing, whereas users of temazepam did not show significant impairments of driving ability. These results reflect the long-acting nature of nitrazepam.

Interactions

Nitrazepam interacts with the antibiotic erythromycin, a strong inhibitor of CYP3A4, which affects concentration peak time. Alone, this interaction is not believed to be clinically important. However, anxiety, tremor, and depression were documented in a case report involving a patient undergoing treatment for acute pneumonia and renal failure. Following administration of nitrazepam, triazolam, and subsequently erythromycin, the patient experienced repetitive hallucinations and abnormal bodily sensations. Coadministration of benzodiazepine drugs at therapeutic doses with erythromycin may cause serious psychotic symptoms, especially in persons with other, significant physical complications.

Oral contraceptive pills reduce the clearance of nitrazepam, which may lead to increased plasma levels of nitrazepam and accumulation. Rifampin significantly increases the clearance of nitrazepam, while probenecid significantly decreases its clearance. Cimetidine slows down the elimination rate of nitrazepam, leading to more prolonged effects and increased risk of accumulation. Alcohol in combination with nitrazepam may cause a synergistic enhancement of the hypotensive properties of both benzodiazepines and alcohol. Benzodiazepines including nitrazepam may inhibit the glucuronidation of morphine, leading to increased levels and prolongation of the effects of morphine in rat experiments.

Pharmacology

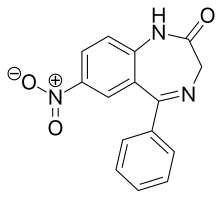

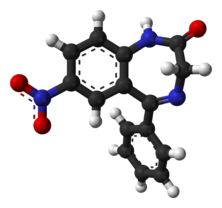

Nitrazepam is a nitrobenzodiazepine. It is a 1,4 benzodiazepine, with the chemical name 1,3-Dihydro-7-nitro-5-phenyl-2H-1,4- benzodiazepin-2-one.

It is long acting, lipophilic, and metabolised hepatically by oxidative pathways. It acts on benzodiazepine receptors in the brain which are associated with the GABA receptors, causing an enhanced binding of GABA to GABAA receptors. GABA is a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, involved in inducing sleepiness, muscular relaxation, and control of anxiety and seizures, and slows down the central nervous system. Nitrazepam is similar in action to the z-drug zopiclone prescribed for insomnia. The anticonvulsant properties of nitrazepam and other benzodiazepines may be in part or entirely due to binding to voltage-dependent sodium channels rather than benzodiazepine receptors. Sustained repetitive firing seems to be limited by benzodiazepines effect of slowing recovery of sodium channels from inactivation in mouse spinal cord cell cultures. The muscle relaxant properties of nitrazepam are produced via inhibition of polysynaptic pathways in the spinal cord of decerebrate cats. It is a full agonist of the benzodiazepine receptor. The endogenous opioid system may play a role in some of the pharmacological properties of nitrazepam in rats. Nitrazepam causes a decrease in the cerebral contents of the amino acids glycine and alanine in the mouse brain. The decrease may be due to activation of benzodiazepine receptors. At high doses decreases in histamine turnover occur as a result of nitrazepam's action at the benzodiazepine-GABA receptor complex in mouse brain. Nitrazepam has demonstrated cortisol-suppressing properties in humans. It is an agonist for both central benzodiazepine receptors and to the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors found in rat neuroblastoma cells.

EEG and sleep

In sleep laboratory studies, nitrazepam decreased sleep onset latency. In psychogeriatric inpatients, it was found to be no more effective than placebo tablets in increasing total time spent asleep and to significantly impair trial subjects' abilities to move and carry out everyday activities the next day, and it should not be used as a sleep aid in psychogeriatric inpatients.

The drug causes a delay in the onset, and decrease in the duration of REM sleep. Following discontinuation of the drug, REM sleep rebound has been reported in some studies. Nitrazepam is reported to significantly affect stages of sleep - a decrease in stage 1, 3, and 4 sleep and an increase in stage 2. In young volunteers, the pharmacological properties of nitrazepam were found to produce sedation and impaired psychomotor performance and standing steadiness. EEG tests showed decreased alpha activity and increased the beta activity, according to blood plasma levels of nitrazepam. Performance was significantly impaired 13 hours after dosing with nitrazepam, as were decision-making skills. EEG tests show more drowsiness and light sleep 18 hours after nitrazepam intake, more so than amylobarbitone. Fast activity was recorded via EEG 18 hours after nitrazepam dosing. An animal study demonstrated that nitrazepam induces a drowsy pattern of spontaneous EEG including high-voltage slow waves and spindle bursts increase in the cortex and amygdala, while the hippocampal theta rhythm is desynchronized. Also low-voltage fast waves occur particularly in the cortical EEG. The EEG arousal response to auditory stimulation and to electric stimulation of the mesencephalic reticular formation, posterior hypothalamus and centromedian thalamus is significantly suppressed. The photic driving response elicited by a flash light in the visual cortex is also suppressed by nitrazepam. Estazolam was found to be more potent however. Nitrazepam increases the slow wave light sleep (SWLS) in a dose-dependent manner whilst suppressing deep sleep stages. Less time is spent in stages 3 and 4 which are the deep sleep stages, when benzodiazepines such as nitrazepam are used. The suppression of deep sleep stages by benzodiazepines may be especially problematic to the elderly as they naturally spend less time in the deep sleep stage.

Pharmacokinetics

Nitrazepam is largely bound to plasma proteins. Benzodiazepines such as nitrazepam are lipid-soluble and have a high cerebral uptake. The time for nitrazepam to reach peak plasma concentrations following oral administration is about 2 hours (0.5 to 5 hours). The half-life of nitrazepam is between 16.5 and 48.3 hours. In young people, nitrazepam has a half-life of about 29 hours and a much longer half-life of 40 hours in the elderly. Both low dose (5 mg) and high dose (10 mg) of nitrazepam significantly increases growth hormone levels in humans.

Nitrazepam's half-life in the cerebrospinal fluid, 68 hours, indicates that nitrazepam is eliminated extremely slowly from the cerebrospinal fluid. Concomitant food intake has no influence on the rate of absorption of nitrazepam nor on its bioavailability. Therefore, nitrazepam can be taken with or without food.

Overdose

Nitrazepam overdose may result in stereotypical symptoms of benzodiazepine overdose including intoxication, impaired balance and slurred speech. In cases of severe overdose this may progress to a comatose state with the possibility of death. The risk of nitrazepam overdose is increased significantly if nitrazepam is abused in conjunction with opioids, as was highlighted in a review of deaths of users of the opioid buprenorphine. Nitrobenzodiazepines such as nitrazepam can result in a severe neurological effects. Nitrazepam taken in overdose is associated with a high level of congenital abnormalities (30 percent of births). Most of the congentital abnormalities were mild deformities.

Severe nitrazepam overdose resulting in coma causes the central somatosensory conduction time (CCT) after median nerve stimulation to be prolonged and the N20 to be dispersed. Brain-stem auditory evoked potentials demonstrate delayed interpeak latencies (IPLs) I-III, III-V and I-V. Toxic overdoses therefore of nitrazepam cause prolonged CCT and IPLs. An alpha pattern coma can be a feature of nitrazepam overdose with alpha patterns being most prominent in the frontal and central regions of the brain.

Benzodiazepines were implicated in 39% of suicides by drug poisoning in Sweden, with nitrazepam and flunitrazepam accounting for 90% of benzodiazepine implicated suicides, in the elderly over a period of 2 decades. In three quarters of cases death was due to drowning, typically in the bath. Benzodiazepines were the predominant drug class in suicides in this review of Swedish death certificates. In 72% of the cases benzodiazepines were the only drug consumed. Benzodiazepines and in particular nitrazepam and flunitrazepam should therefore be prescribed with caution in the elderly. In a brain sample of a fatal nitrazepam poisoning high concentrations of nitrazepam and its metabolite were found in the brain of the deceased person.

In a retrospective study of deaths in Sweden, when benzodiazepines were implicated in the deaths, the benzodiazepines nitrazepam and flunitrazepam were the most common benzodiazepines involved. Benzodiazepines were a factor in all deaths related to drug addiction in this study of causes of deaths. In Sweden, nitrazepam and flunitrazepam were significantly more commonly implicated in suicide related deaths than natural deaths. In four of the cases benzodiazepines alone were the only cause of death. In Australia, nitrazepam and temazepam were the benzodiazepines most commonly detected in overdose drug related deaths. In a third of cases benzodiazepines were the sole cause of death.

Individuals with chronic illnesses are much more vulnerable to lethal overdose with nitrazepam, as fatal overdoses can occur at relatively low doses in these individuals.

Synthesis

Reaction of 2-amino-5-nitrobenzophenone (1) with bromoacetyl bromide forms the amide 2. Ring closure in liquid ammonia affords nitrazepam (3). More simply, diazepinone (4) can be nitrated directly at the more reactive C7 position with potassium nitrate in sulfuric acid.

See also

- Benzodiazepine

- Benzodiazepine dependence

- Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome

- Long-term effects of benzodiazepines

- Nimetazepam — methylamino derivative of nitrazepam

- Flunitrazepam — fluorinated methylamino derivative

- Clonazepam — chlorinated derivative

- Fulgazepam - light-activated derivative of benzodiazepine based on photoisomerizable fulgimide

References

- Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- "Benzodiazepine Names". non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- "INSOMIN tabletti 5 mg". laaketietokeskus.fi.

- "Hypnotics and anxiolytics". BNF. Retrieved 2014-08-14.

- Yasui M, Kato A, Kanemasa T, Murata S, Nishitomi K, Koike K, et al. (June 2005). "". Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi = Japanese Journal of Psychopharmacology. 25 (3): 143–151. OCLC 111086408. PMID 16045197.

- "Benzodiazepines". Release. 2013-04-09. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 537. ISBN 9783527607495.

- Tanaka M, Suemaru K, Watanabe S, Cui R, Li B, Araki H (July 2008). "Comparison of short- and long-acting benzodiazepine-receptor agonists with different receptor selectivity on motor coordination and muscle relaxation following thiopental-induced anesthesia in mice". Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 107 (3): 277–284. doi:10.1254/jphs.FP0071991. PMID 18603831.

- ^ Tsao CY (May 20, 2009). "Current trends in the treatment of infantile spasms". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 5: 289–299. doi:10.2147/ndt.s4488. PMC 2695218. PMID 19557123.

- Isojärvi JI, Tokola RA (December 1998). "Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy in people with intellectual disability". Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 42 Suppl 1 (1): 80–92. PMID 10030438.

- ^ Rustler K, Maleeva G, Gomila AM, Gorostiza P, Bregestovski P, König B (October 2020). "Optical Control of GABAA Receptors with a Fulgimide-Based Potentiator". Chemistry: A European Journal. 26 (56): 12722–12727. doi:10.1002/chem.202000710. PMC 7589408. PMID 32307732.

- "Benzodiazepine Equivalents Table - A list of Equivalent Doses of Benzodiazepines". www.non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 17 July 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- Vermeeren A (2004). "Residual effects of hypnotics: epidemiology and clinical implications". CNS Drugs. 18 (5): 297–328. doi:10.2165/00023210-200418050-00003. PMID 15089115. S2CID 25592318.

- ^ Hossmann V, Maling TJ, Hamilton CA, Reid JL, Dollery CT (August 1980). "Sedative and cardiovascular effects of clonidine and nitrazepam". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 28 (2): 167–176. doi:10.1038/clpt.1980.146. PMID 7398184. S2CID 71760513.

- Impallomeni M, Ezzat R (January 1976). "Letter: Hypothermia associated with nitrazepam administration". British Medical Journal. 1 (6003): 223–224. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2665.223. PMC 1638481. PMID 1247796.

- ^ Mizuno K, Katoh M, Okumura H, Nakagawa N, Negishi T, Hashizume T, et al. (February 2009). "Metabolic activation of benzodiazepines by CYP3A4". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 37 (2): 345–351. doi:10.1124/dmd.108.024521. PMID 19005028. S2CID 5688931.

- Kim HB, Myung SK, Park YC, Park B (February 2017). "Use of benzodiazepine and risk of cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies". International Journal of Cancer. 140 (3): 513–525. doi:10.1002/ijc.30443. PMID 27667780.

- Brandt J, Leong C (December 2017). "Benzodiazepines and Z-Drugs: An Updated Review of Major Adverse Outcomes Reported on in Epidemiologic Research". Drugs in R&D. 17 (4): 493–507. doi:10.1007/s40268-017-0207-7. PMC 5694420. PMID 28865038.

- Rintahaka PJ, Nakagawa JA, Shewmon DA, Kyyronen P, Shields WD (April 1999). "Incidence of death in patients with intractable epilepsy during nitrazepam treatment". Epilepsia. 40 (4): 492–496. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00746.x. PMID 10219277. S2CID 10133690.

- Lim HC, Nigro MA, Beierwaltes P, Tolia V, Wishnow R (September 1992). "Nitrazepam-induced cricopharyngeal dysphagia, abnormal esophageal peristalsis and associated bronchospasm: probable cause of nitrazepam-related sudden death". Brain & Development. 14 (5): 309–314. doi:10.1016/s0387-7604(12)80149-5. PMID 1456385. S2CID 23523653.

- Ashton H (May 2005). "The diagnosis and management of benzodiazepine dependence". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 18 (3): 249–255. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000165594.60434.84. PMID 16639148. S2CID 1709063.

- Ashton H (2004). "Benzodiazepine dependence". In Haddad P, Dursun S, Deakin B (eds.). Adverse Syndromes and Psychiatric Drugs: A Clinical Guide. Oxford University Press. pp. 239–60. ISBN 978-0-19-852748-0.

- Grossi CM, Richardson K, Fox C, Maidment I, Steel N, Loke YK, et al. (October 2019). "Anticholinergic and benzodiazepine medication use and risk of incident dementia: a UK cohort study". BMC Geriatrics. 19 (1): 276. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1280-2. PMC 6802337. PMID 31638906.

- Hoffmann–La Roche. "Mogadon". RxMed. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Adam K, Adamson L, Brezinová V, Hunter WM (June 1976). "Nitrazepam: lastingly effective but trouble on withdrawal". British Medical Journal. 1 (6025): 1558–1560. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.6025.1558. PMC 1640482. PMID 179657.

- Oswald I, French C, Adam K, Gilham J (March 1982). "Benzodiazepine hypnotics remain effective for 24 weeks". British Medical Journal. 284 (6319): 860–863. doi:10.1136/bmj.284.6319.860. PMC 1496323. PMID 6121605.

- Kangas L, Kanto J, Lehtinen V, Salminen J (May 1979). "Long-term nitrazepam treatment in psychiatric out-patients with insomnia". Psychopharmacology. 63 (1): 63–66. doi:10.1007/BF00426923. PMID 112623. S2CID 27388443.

- Străulea AO, Chiriţă V (July–September 2009). "[The withdrawal syndrome in benzodiazepine dependence and its management]" [The withdrawal syndrome in benzodiazepine dependence and its management]. Revista Medico-Chirurgicala a Societatii de Medici Si Naturalisti Din Iasi (in Romanian). 113 (3): 879–884. PMID 20191849.

- Kales A, Scharf MB, Kales JD, Soldatos CR (April 1979). "Rebound insomnia. A potential hazard following withdrawal of certain benzodiazepines". JAMA. 241 (16): 1692–1695. doi:10.1001/jama.241.16.1692. PMID 430730.

- ^ Authier N, Balayssac D, Sautereau M, Zangarelli A, Courty P, Somogyi AA, et al. (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises. 67 (6): 408–413. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- Lahtinen U, Lahtinen A, Pekkola P (February 1978). "The effect of nitrazepam on manual skill, grip strength, and reaction time with special reference to subjective evaluation of effects on sleep". Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica. 42 (2): 130–134. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1978.tb02180.x. PMID 343500.

- Kozená L, Frantik E, Horváth M (May 1995). "Vigilance impairment after a single dose of benzodiazepines". Psychopharmacology. 119 (1): 39–45. doi:10.1007/BF02246052. PMID 7675948. S2CID 2618084.

- ^ Törnros J, Laurell H (July 1990). "Acute and carry-over effects of brotizolam compared to nitrazepam and placebo in monotonous simulated driving". Pharmacology & Toxicology. 67 (1): 77–80. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1990.tb00786.x. PMID 2395820.

- ^ Gustavsen I, Bramness JG, Skurtveit S, Engeland A, Neutel I, Mørland J (December 2008). "Road traffic accident risk related to prescriptions of the hypnotics zopiclone, zolpidem, flunitrazepam and nitrazepam". Sleep Medicine. 9 (8): 818–822. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2007.11.011. hdl:10852/34650. PMID 18226959.

- ^ Mets MA, Volkerts ER, Olivier B, Verster JC (August 2010). "Effect of hypnotic drugs on body balance and standing steadiness". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 14 (4): 259–267. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.008. PMID 20171127.

- ^ Kangas L, Iisalo E, Kanto J, Lehtinen V, Pynnönen S, Ruikka I, et al. (April 1979). "Human pharmacokinetics of nitrazepam: effect of age and diseases". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 15 (3): 163–170. doi:10.1007/bf00563100. PMID 456400. S2CID 19791755.

- ^ Vozeh S (November 1981). "". Schweizerische Medizinische Wochenschrift. 111 (47): 1789–1793. PMID 6118950.

- ^ Ericsson HR, Holmgren P, Jakobsson SW, Lafolie P, De Rees B (November 1993). "". Läkartidningen. 90 (45): 3954–3957. PMID 8231567.

- ^ Drummer OH, Ranson DL (December 1996). "Sudden death and benzodiazepines". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 17 (4): 336–342. doi:10.1097/00000433-199612000-00012. PMID 8947361.

- ^ Carlsten A, Waern M, Holmgren P, Allebeck P (2003). "The role of benzodiazepines in elderly suicides". Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 31 (3): 224–228. doi:10.1080/14034940210167966. PMID 12850977. S2CID 24102880.

- ^ Gidai J, Acs N, Bánhidy F, Czeizel AE (February 2010). "Congenital abnormalities in children of 43 pregnant women who attempted suicide with large doses of nitrazepam". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 19 (2): 175–182. doi:10.1002/pds.1885. PMID 19998314. S2CID 25856700.

- Ashton CH (2002). "BENZODIAZEPINE ABUSE". Drugs and Dependence. Harwood Academic Publishers. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- Garretty DJ, Wolff K, Hay AW, Raistrick D (January 1997). "Benzodiazepine misuse by drug addicts". Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 34 ( Pt 1) (Pt 1): 68–73. doi:10.1177/000456329703400110. PMID 9022890. S2CID 42665843.

- Chatterjee A, Uprety L, Chapagain M, Kafle K (1996). "Drug abuse in Nepal: a rapid assessment study". Bulletin on Narcotics. 48 (1–2): 11–33. PMID 9839033.

- Hindmarch I, Parrott AC (1980). "The effects of combined sedative and anxiolytic preparations on subjective aspects of sleep and objective measures of arousal and performance the morning following nocturnal medication. I: Acute doses". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 30 (6): 1025–1028. PMID 6106498.

- Shats V, Kozacov S (June 1995). "". Harefuah. 128 (11): 690–3, 743. PMID 7557666.

- Borland RG, Nicholson AN (February 1975). "Comparison of the residual effects of two benzodiazepines (nitrazepam and flurazepam hydrochloride) and pentobarbitone sodium on human performance". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1975.tb00465.x. PMC 1402497. PMID 10941.

- Evans JG, Jarvis EH (November 1972). "Nitrazepam and the elderly". British Medical Journal. 4 (5838): 487. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5838.487-a. PMC 1786736. PMID 4653884.

- Trewin VF, Lawrence CJ, Veitch GB (April 1992). "An investigation of the association of benzodiazepines and other hypnotics with the incidence of falls in the elderly". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 17 (2): 129–133. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.1992.tb00750.x. PMID 1349894.

- Greenblatt DJ, Allen MD (May 1978). "Toxicity of nitrazepam in the elderly: a report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 5 (5): 407–413. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1978.tb01646.x. PMC 1429343. PMID 656280.

- Castleden CM, George CF, Marcer D, Hallett C (January 1977). "Increased sensitivity to nitrazepam in old age". British Medical Journal. 1 (6052): 10–12. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.157.10. PMC 1603636. PMID 318894.

- Dennis J, Hunt A (September 1985). "Prolonged use of nitrazepam for epilepsy in children with tuberous sclerosis". British Medical Journal. 291 (6497): 692–693. doi:10.1136/bmj.291.6497.692. PMC 1416679. PMID 3929902.

- ^ McElhatton PR (November–December 1994). "The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation". Reproductive Toxicology. 8 (6): 461–475. Bibcode:1994RepTx...8..461M. doi:10.1016/0890-6238(94)90029-9. PMID 7881198.

- Janknegt R, van der Kuy A, Declerck G, Idzikowski C (August 1996). "Hypnotics. Drug selection by means of the System of Objectified Judgement Analysis (SOJA) method". PharmacoEconomics. 10 (2): 152–163. doi:10.2165/00019053-199610020-00007. PMID 10163418.

- Serreau R (April 2010). "". Annales Françaises d'Anesthésie et de Réanimation. 29 (4): e37 – e46. doi:10.1016/j.annfar.2010.02.016. PMID 20347563.

- Olive G, Dreux C (January 1977). "". Archives Françaises de Pédiatrie. 34 (1): 74–89. PMID 851373.

- Kangas L, Kanto J, Erkkola R (December 1977). "Transfer of nitrazepam across the human placenta". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 12 (5): 355–357. doi:10.1007/BF00562451. PMID 598407. S2CID 21227168.

- Kanto JH (May 1982). "Use of benzodiazepines during pregnancy, labour and lactation, with particular reference to pharmacokinetic considerations". Drugs. 23 (5): 354–380. doi:10.2165/00003495-198223050-00002. PMID 6124415. S2CID 27014006.

- Kenny RA, Kafetz K, Cox M, Timmers J, Impallomeni M (April 1984). "Impaired nitrazepam metabolism in hypothyroidism". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 60 (702): 296–297. doi:10.1136/pgmj.60.702.296. PMC 2417841. PMID 6728755.

- Midgren B, Hansson L, Ahlmann S, Elmqvist D (1990). "Effects of single doses of propiomazine, a phenothiazine hypnotic, on sleep and oxygenation in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Respiration; International Review of Thoracic Diseases. 57 (4): 239–242. doi:10.1159/000195848. PMID 1982774.

- O'Hanlon JF, Volkerts ER (1986). "Hypnotics and actual driving performance". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 332: 95–104. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb08985.x. PMID 3554901. S2CID 44982782.

- Luurila H, Olkkola KT, Neuvonen PJ (April 1995). "Interaction between erythromycin and nitrazepam in healthy volunteers". Pharmacology & Toxicology. 76 (4): 255–258. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1995.tb00139.x. PMID 7617555.

- Tokinaga N, Kondo T, Kaneko S, Otani K, Mihara K, Morita S (December 1996). "Hallucinations after a therapeutic dose of benzodiazepine hypnotics with co-administration of erythromycin". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 50 (6): 337–339. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.1996.tb00577.x. PMID 9014234. S2CID 22742117.

- Back DJ, Orme ML (June 1990). "Pharmacokinetic drug interactions with oral contraceptives". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 18 (6): 472–484. doi:10.2165/00003088-199018060-00004. PMID 2191822. S2CID 32523973.

- Brockmeyer NH, Mertins L, Klimek K, Goos M, Ohnhaus EE (September 1990). "Comparative effects of rifampin and/or probenecid on the pharmacokinetics of temazepam and nitrazepam". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Therapy, and Toxicology. 28 (9): 387–393. PMID 2228325.

- Ochs HR, Greenblatt DJ, Gugler R, Müntefering G, Locniskar A, Abernethy DR (August 1983). "Cimetidine impairs nitrazepam clearance". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 34 (2): 227–230. doi:10.1038/clpt.1983.157. PMID 6872417. S2CID 97229669.

- Zácková P, Kvĕtina J, Nĕmec J, Nĕmcová J (December 1982). "Cardiovascular effects of diazepam and nitrazepam in combination with ethanol". Die Pharmazie. 37 (12): 853–856. PMID 7163374.

- Pacifici GM, Gustafsson LL, Säwe J, Rane A (April 1986). "Metabolic interaction between morphine and various benzodiazepines". Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica. 58 (4): 249–252. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1986.tb00103.x. PMID 2872767.

- Robertson MD, Drummer OH (May 1995). "Postmortem drug metabolism by bacteria". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 40 (3): 382–386. doi:10.1520/JFS13791J. PMID 7782744.

- Danneberg P, Weber KH (1983). "Chemical structure and biological activity of the diazepines". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 16 (Suppl 2): 231S – 244S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb02295.x. PMC 1428206. PMID 6140944.

- Skerritt JH, Johnston GA (May 1983). "Enhancement of GABA binding by benzodiazepines and related anxiolytics". European Journal of Pharmacology. 89 (3–4): 193–198. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(83)90494-6. PMID 6135616.

- Sato K, Hong YL, Yang MS, Shibuya T, Kawamoto H, Kitagawa H (April 1985). "Pharmacologic studies of central actions of zopiclone: influence on brain monoamines in rats under stressful condition". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Therapy, and Toxicology. 23 (4): 204–210. PMID 2860074.

- McLean MJ, Macdonald RL (February 1988). "Benzodiazepines, but not beta carbolines, limit high frequency repetitive firing of action potentials of spinal cord neurons in cell culture". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 244 (2): 789–795. PMID 2450203.

- Date SK, Hemavathi KG, Gulati OD (November 1984). "Investigation of the muscle relaxant activity of nitrazepam". Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Thérapie. 272 (1): 129–139. PMID 6517646.

- Podhorna J, Krsiak M (April 2000). "Behavioural effects of a benzodiazepine receptor partial agonist, Ro 19-8022, in the social conflict test in mice". Behavioural Pharmacology. 11 (2): 143–151. doi:10.1097/00008877-200004000-00006. PMID 10877119. S2CID 27601469.

- Nowakowska E, Chodera A (February 1991). "Studies on the involvement of opioid mechanism in the locomotor effects of benzodiazepines in rats". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 38 (2): 265–266. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(91)90276-8. PMID 1676167. S2CID 35953710.

- Tomono S, Kuriyama K (December 1985). "Effect of 450191-S, a 1H-1,2,4-triazolyl benzophenone derivative, on cerebral content of neuroactive amino acids". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 39 (4): 558–561. doi:10.1254/jjp.39.558. PMID 2869172.

- Oishi R, Nishibori M, Itoh Y, Saeki K (May 1986). "Diazepam-induced decrease in histamine turnover in mouse brain". European Journal of Pharmacology. 124 (3): 337–342. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(86)90236-0. PMID 3089825.

- Christensen P, Lolk A, Gram LF, Kragh-Sørensen P (1992). "Benzodiazepine-induced sedation and cortisol suppression. A placebo-controlled comparison of oxazepam and nitrazepam in healthy male volunteers". Psychopharmacology. 106 (4): 511–516. doi:10.1007/BF02244823. PMID 1349754. S2CID 29331503.

- Watabe S, Yoshii M, Ogata N, Tsunoo A, Narahashi T (March 1993). "Differential inhibition of transient and long-lasting calcium channel currents by benzodiazepines in neuroblastoma cells". Brain Research. 606 (2): 244–250. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(93)90991-U. PMID 8387860. S2CID 40892187.

- Linnoila M, Viukari M (June 1976). "Efficacy and side effects of nitrazepam and thioridazine as sleeping aids in psychogeriatric in-patients". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 128 (6): 566–569. doi:10.1192/bjp.128.6.566. PMID 776314. S2CID 45948499.

- Adam K, Oswald I (July 1982). "A comparison of the effects of chlormezanone and nitrazepam on sleep". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 14 (1): 57–65. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1982.tb04934.x. PMC 1427586. PMID 7104168.

- Mizuki Y, Suetsugi M, Hotta H, Ushijima I, Yamada M (May 1995). "Stimulatory effect of butoctamide hydrogen succinate on REM sleep in normal humans". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 19 (3): 385–401. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(95)00020-V. PMID 7624490. S2CID 25074381.

- Tazaki T, Tada K, Nogami Y, Takemura N, Ishikawa K (1989). "Effects of butoctamide hydrogen succinate and nitrazepam on psychomotor function and EEG in healthy volunteers". Psychopharmacology. 97 (3): 370–375. doi:10.1007/BF00439453. PMID 2497487. S2CID 24330487.

- Malpas A, Rowan AJ, Boyce CR, Scott DF (June 1970). "Persistent behavioural and electroencephalographic changes after single doses of nitrazepam and amylobarbitone sodium". British Medical Journal. 2 (5712): 762–764. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.3382.762. PMC 1700857. PMID 4913785.

- Watanabe S, Ohta H, Sakurai Y, Takao K, Ueki S (July 1986). "[Electroencephalographic effects of 450191-S and its metabolites in rabbits with chronic electrode implants]". Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. Folia Pharmacologica Japonica. 88 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1254/fpj.88.19. PMID 3758874.

- Noguchi H, Kitazumi K, Mori M, Shiba T (March 2004). "Electroencephalographic properties of zaleplon, a non-benzodiazepine sedative/hypnotic, in rats". Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 94 (3): 246–251. doi:10.1254/jphs.94.246. PMID 15037809.

- Tokola RA, Neuvonen PJ (1983). "Pharmacokinetics of antiepileptic drugs". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 97: 17–27. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.1983.tb01532.x. PMID 6143468. S2CID 25137468.

- Hertz MM, Paulson OB (May 1980). "Heterogeneity of cerebral capillary flow in man and its consequences for estimation of blood-brain barrier permeability". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 65 (5): 1145–1151. doi:10.1172/JCI109769. PMC 371448. PMID 6988458.

- Kangas L, Kanto J, Syvälahti E (July 1977). "Plasma nitrazepam concentrations after an acute intake and their correlation to sedation and serum growth hormone levels". Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica. 41 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1977.tb02124.x. PMID 331868.

- Kangas L, Kanto J, Siirtola T, Pekkarinen A (July 1977). "Cerebrospinal-fluid concentrations of nitrazepam in man". Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica. 41 (1): 74–79. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1977.tb02125.x. PMID 578380.

- Holm V, Melander A, Wåhlin-Boll E (1982). "Influence of food and of age on nitrazepam kinetics". Drug-Nutrient Interactions. 1 (4): 307–311. PMID 6926838.

- Lai SH, Yao YJ, Lo DS (October 2006). "A survey of buprenorphine related deaths in Singapore". Forensic Science International. 162 (1–3): 80–86. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.03.037. PMID 16879940.

- Linwu SW, Syu CJ, Chen YL, Wang AH, Peng FC (July 2009). "Characterization of Escherichia coli nitroreductase NfsB in the metabolism of nitrobenzodiazepines". Biochemical Pharmacology. 78 (1): 96–103. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2009.03.019. PMID 19447228.

- Carroll WM, Mastiglia FL (December 1977). "Alpha and beta coma in drug intoxication". British Medical Journal. 2 (6101): 1518–1519. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.6101.1518-a. PMC 1632784. PMID 589310.

- Rumpl E, Prugger M, Battista HJ, Badry F, Gerstenbrand F, Dienstl F (December 1988). "Short latency somatosensory evoked potentials and brain-stem auditory evoked potentials in coma due to CNS depressant drug poisoning. Preliminary observations". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 70 (6): 482–489. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(88)90146-0. PMID 2461282.

- Moriya F, Hashimoto Y (January 2003). "Tissue distribution of nitrazepam and 7-aminonitrazepam in a case of nitrazepam intoxication". Forensic Science International. 131 (2–3): 108–112. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(02)00421-8. PMID 12590048.

- Brødsgaard I, Hansen AC, Vesterby A (June 1995). "Two cases of lethal nitrazepam poisoning". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 16 (2): 151–153. doi:10.1097/00000433-199506000-00015. PMID 7572872. S2CID 11306468.

- Sternbach LH, Fryer RI, Keller O, Metlesics W, Sach G, Steiger N (May 1963). "Quinazolines and 1,4-Benzodiazepines. X. Nitro-Substituted 5-Phenyl-1,4-Benzodiazepine Derivatives". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (3): 261–265. doi:10.1021/jm00339a010. PMID 14185980.

- US patent 3121076, Keller O, "Benzodiazepinones and Processes", published 11 February 1964, assigned to Hoffmann-La Roche

External links

| Hypnotics/sedatives (N05C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GABAA |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GABAB | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H1 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| α2-Adrenergic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5-HT2A |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melatonin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Orexin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| α2δ VDCC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GABAA receptor positive modulators | |

|---|---|

| Alcohols | |

| Barbiturates |

|

| Benzodiazepines |

|

| Carbamates | |

| Flavonoids |

|

| Imidazoles | |

| Kava constituents | |

| Monoureides | |

| Neuroactive steroids |

|

| Nonbenzodiazepines | |

| Phenols | |

| Piperidinediones | |

| Pyrazolopyridines | |

| Quinazolinones | |

| Volatiles/gases |

|

| Others/unsorted |

|

| See also: Receptor/signaling modulators • GABA receptor modulators • GABA metabolism/transport modulators | |